Retroviral insertional mutagenesis in inbred mouse strains provides a powerful method for cancer gene discovery. Here, we show that a common retroviral integration site (RIS) in AKXD B-cell lymphomas, termed Evi3, encodes a novel zinc finger protein with 30 Krüppel-like zinc finger repeats. Most integrations atEvi3 are located upstream of the first translated exon and result in 3′ long-terminal repeat (LTR)–driven overexpression ofEvi3. Evi3 is highly related to the early B-cell factor–associated zinc finger gene (Ebfaz), and all 30 zinc fingers found in EVI3 are conserved in EBFAZ. EBFAZ binds to and negatively regulates early B-cell factor (EBF) (also known as olfactory-1, OLF1), a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor required for B-lineage commitment and the development of the olfactory epithelium. EBFAZ also binds to SMA- and MAD-related protein–1 (SMAD1) and SMAD4 in response to bone morphogenetic protein–2 (BMP2) signaling, which in turn activates the homeobox regulator of Xenopus mesoderm and neural development Xvent-2. Surprisingly, while Ebfazand Evi3 are coexpressed in many tissues, and both proteins are nuclear, we could not detect Ebfaz expression in B cells by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), whereas Evi3 expression could be detected at all stages of B-cell development. Our results suggest that EVI3, like EBFAZ, is a multifunctional protein that participates in many signaling pathways via its multiple zinc fingers. Furthermore, our results suggest that EVI3, not EBFAZ, is the member of this protein family that interacts with and regulates EBF in B cells.

Introduction

Several recombinant inbred (RI) strains have been developed as model systems for identifying and studying genes causally associated with hematopoietic disease. One of the more informative sets of RI strains is the AKXD RI strain family. This family of strains was derived from a cross of AKR/J mice, which have a high incidence of retrovirally induced T-cell lymphoma, with DBA/2J mice, a low-lymphomatous strain.1 Unexpectedly, the AKXD strains differ among themselves and from their parents in lymphoma susceptibility, lymphoma cell type, average age of disease onset, and viral content.1,2 Among the 21 highly lymphomatous AKXD RI strains, only 6 develop T-cell lymphoma like their AKR/J parent. In contrast, 7 strains develop B-cell lymphoma; 7 strains develop a mixture of B- and T-cell lymphoma; and 1 strain dies from myeloid disease. These results suggest that one or more genes that affect tumor cell type segregated during the inbreeding of these strains, a hypothesis that is supported by the identification of a dominant host gene, Tlsm1 (thymic lymphoma susceptible mouse 1), that predisposes AKXD mice to T-cell disease.3

More than 150 loci that are targets of retroviral integration in 2 or more AKXD tumors (subsequently referred to as common retroviral integration sites [CISs]), and therefore likely to encode a disease gene, have been identified by retroviral insertional mutagenesis in AKXD mice.4 5 Thirty-six of these CISs encode known, suspected, or homologs of human cancer genes, validating the usefulness of retroviral insertional mutagenesis for human cancer gene identification. In addition, many other CISs encode excellent disease gene candidates, but a role for these genes in human disease has not yet been examined. Collectively, these results demonstrate the power of retroviral insertional mutagenesis for cancer gene identification in the postgenome era and suggest that retroviral insertional mutagenesis might be useful for identifying cancer genes that are not easy to identify directly in humans.

One of the CISs identified in AKXD tumors is Evi3 (ecotropic viral integration site 3).6 More than 9% of AKXD B-cell lymphomas contain a retroviral integration at Evi3. In contrast, Evi3 is never targeted in AKXD T-cell or myeloid tumors, suggesting that it encodes a B-cell disease gene. The frequency of viral integration at Evi3 also varies according to strain. In most AKXD strains, Evi3 is infrequently or never targeted. However in the AKXD27 strain, Evi3 is targeted in 70% of the lymphomas.6 Despite considerable effort, a candidate disease gene for Evi3 was never identified.Evi3 is nonetheless interesting because of its frequent association with B-cell disease. In addition, integrations atEvi3 are not exclusive to AKXD tumors, as one pre-B lymphoma cell line (NFS-467), induced by infection of NFS mice with a recombinant Cas-Br-M virus carrying the Cbloncogene, harbors a viral integration at Evi3.6Evi3 may therefore cooperate with Cbl in tumor induction.

In studies described here, we show that Evi3 encodes a novel, Ebfaz-related Krüppel-like zinc finger gene. All 30 Krüppel-like zinc fingers found in EBFAZ are conserved in EVI3. We also show that Evi3 is expressed in tissues and cells expressing Ebfaz and that EBFAZ and EVI3 proteins are located in the nucleus. Surprisingly, Ebfaz is not expressed in B cells, whereas Evi3 is expressed in all stages of B-cell development. EVI3, like EBFAZ, may thus function in several different signaling pathways using different clusters of zinc fingers. Importantly, EVI3 probably serves the function formerly attributed to EBFAZ in B cells, including one or more pathways important for B-lineage commitment. Deregulation of these pathways by viral integration may, in part, explain the role of Evi3 in B-cell disease.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics

Evi3 sequences were BLAST (basic local alignment search tool)–searched against the mouse genome sequence by means of the Celera Discovery System (http://www.Celera.com; accessed November 20, 2002) and the public Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium database (http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus; accessed November 20, 2002) to identify Evi3 candidate disease genes. The intron/exon structure of Evi3 was determined by comparing anEvi3 mouse cDNA sequence available from GenBank with genomic sequences (Evi3 cDNA accession no. BC021376).

Southern hybridization

Genomic DNA from AKXD27 tumors was purified by means of standard procedures. For analysis of Evi3 viral integrations, 5 μgSacI-digested genomic DNA was used. TheSacI blot was hybridized with a 32P random-labeled (Megaprime, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) P3-1Evi3 probe as described.6 Restriction fragment sizes were determined with the use of HindIII-digested λ markers, which were labeled along with the P3-1 probe.

Northern hybridization

A multiple mouse tissue polyA Northern blot (Origene Technologies, Rockville, MD) was hybridized with a 32P random-labeled ApaI-NotI 3′ untranslated region (UTR) Evi3 cDNA fragment with the use of standard methods. A 3′ UTR probe for Ebfaz was generated from clonedEbfaz cDNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the use of the following primers: 5052197, 5′-GCTCCAGCTAGTGTGCTTTTA-3′; and 5023712 5′–GCTGATCGCATGGATTCCCT-3′ (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). PCR was performed with the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for 25 cycles at 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, with the use of 10 ng cDNA template. This fragment was also labeled by random labeling. The Gapd control probe was labeled by nick translation (Roche).

Identification and cloning of retroviral integration sites

The cloning and identification of viral integration sites in tumors x001, 010, 008, 399, and 146 is described elsewhere.4 The Evi3 integration sites from AKXD27 tumors 22, 27, and 29 were cloned with the use ofSacI-digested and self-ligated genomic DNA followed by nested inverse PCR (IPCR). The Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche) was used for PCR amplification according to the manufacturer's protocol. We used 1 μL from the first round of PCR as template in the second round. Evi3-specific genomic primers used for PCR (Integrated DNA Technologies) were as follows: first round, 4632635, 5′-GACCTCTCGGCTCCTTGATT-3′, and 4632637, 5′-GGCTGACCCTGGATTTTGTGT-3′; second round, 4632636, 5′-CTCTGCTCGCCACATTCCAA-3′, and 4632638, 5′-CACTCAGACACCCTGTGACA-3′. PCR conditions were 10 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 61°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by 20 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 61°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes with a 5-second extension per cycle. The resulting bands were cloned and sequenced.

5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends

Evi3 and Ebfaz 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was performed with the use of the Marathon-Ready cDNA kit (Clontech, BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) from mouse spleen together with the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche). We used the set of RACE adapter primers included in the kit together with Evi3 or Ebfaz primers, following the manufacturer's suggestions. Primers used for Evi3 5′RACE were as follows: 1st round, 4653763, 5′-GCAGTAGGTGCACTTGAAGGGCAGCTTG-3′; and 2nd round, 4594271, 5′-GTTGGGGTCTTTGAGGGATCTCGGT-3′. For Ebfaz, 5′ RACE primers were as follows: 1st round, 4774319, 5′-AGGCCGAGGTCACAACCATCTCCTATCATC-3′; and 2nd round, 4594272, 5′-ATCACACTCTGGCTCTCCTTCCAGG-3′. PCR conditions were 5 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by 5 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 70°C for 2 minutes, and 25 to 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds and 68°C for 2 minutes. Primers were from Integrated DNA Technologies.

cDNA cloning

Primers based on the published cDNA sequences, and 5′ RACE results were used to PCR-amplify overlapping cDNA fragments from the Marathon-Ready spleen cDNA kit (Clontech, BD Biosciences) with the use of the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche). Evi3 cDNA was cloned into pBluescript SK− (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in 3 steps with the use of 2 internal EcoRI sites and by adding a 5′ SalI and a 3′ NotI site. Primers used (Integrated DNA Technologies) were as follows (added restriction sites are underlined, and the positions in the cDNA sequence are indicated in parentheses): Evi3 5′ fragment 4754821 (1-22), 5′-AATTTTGTCGACAGTGATTACGTACAGAGCGAGT-3′; and 4754823 (2192-2172), 5′-GATGGTCACGTGCTTTAGCAA-3′. Evi3 middle fragment 4754822 (2085-2105), 5′-CAGACTCACCTCAAAACCCAT-3′; and 4754825 (3254-3234), 5′-CCCGTGGATTTTGAGTTCCAA-3′. Evi33′ fragment 4754824 (2875-2893), 5′-CTGGAGAAAGCGCCATCGT-3′; and 4754826 (4852-4825), 5′-AATTTAGCGGCCGCGATGGTAAACTGAATTTATTTCCTCTTG-3′. PCR conditions were 10 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 68°C for 4 minutes, followed by 25 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 68°C for 4 minutes with a 5-second extension per cycle. As template, 1 μL Marathon-Ready cDNA was used.

In a similar manner, Ebfaz cDNA was cloned into pBluescript SK− with the use of 2 PCR fragments. Primers used for PCR were as follows (with added restriction sites indicated by underlining, and positions given in parentheses): Ebfaz 5′ fragment 5023709 (1-17), 5′-AAAATAGTCGACCACGGGGGACCTCAGAA-3′; and 5023710 (2800-2781), 5′-CCGAGAGCACACGTTACACT-3′. Ebfaz 3′ fragment 5023711 (2677-2696), 5′-CATGGAGGTGTTGCTGCAGA-3′; and 5023712 (4441-4422), 5′-AAAATAGCGGCCGCGCTGATCGC- ATGGATTCCCT-3′. The cloned cDNAs were subjected to extensive restriction analysis and sequencing.

RNA purification and RNase protection

RNA was extracted from tumor samples by means of the TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA used for RNase protection assay (RPA) was subjected to DNase treatment (Promega, Madison, WI). Approximately 10 μg RNA from each tumor was used in the protection assay. The RPAIII kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. All in vitro transcription was performed with the use of the T7 version of MAXIscript (Ambion). Cyclophilin(pTRI-cyclophilin template from Ambion) was used as an internal control. 32P-labeled RNA markers were synthesized by means of the RNA Century Marker Template set, T7 version (Ambion). The DNA template for antisense in vitro transcription of Evi3 andEbfaz was amplified by PCR (High Fidelity PCR kit; Roche) from the Marathon-ready cDNA (spleen; Clontech, BD Biosciences) and cloned into BamHI-NotI–digested pBluescript SK− (Stratagene). Then, 1 μg DNA template was linearized with NotI, phenol/chloroform extracted, precipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in ddH2O prior to in vitro transcription. Primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) used for the DNA templates were located in separate exons to avoid false-positive bands from residual DNA, and the sequences were as follows (recognition sites for NotI and BamHI are underlined):Evi3 primers 4877612, 5′-AAATAAGCGGCCGCAGGCAGTAGACTGCAAGAAGA-3; and 4877613, 5′-AAATAAGGATCCGCTTGTCACTATGGCTCTGTT-3. For in vitro transcription, 32P-labeled α–uridine triphosphate (α-UTP) (Amersham Biosciences) was used, and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed with 6% PAGE/UREA (Ambion). Approximately 25 000 cpm of each gel-purified probe was used per RNA sample.

Reverse-transcriptase PCR

B cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (BD Biosciences), with the use of either the B220+ pan-B marker for splenocytes or a 2-step sorting procedure for bone marrow cells: First, cells stained with immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgD antibodies were sorted. IgM+IgD− (immature B cells) and IgM+IgD+ (mature B cells) were saved for RNA extraction and reverse transcription. The double-negative cells from the first round (consisting of myeloid, T-, and early B-cell fractions) were stained with CD43 and B220 and sorted. B220+CD43+ (pro-B cells) and B220+CD43− (pre-B cells) were saved for RNA and reverse transcription. All antibodies (rat antimouse IgD–fluorescein isothiocyanate [IgD-FITC], IgM-phycoerythrin [IgM-PE], CD43-FITC, and B220-PE) were from Pharmingen (BD Biosciences). Total RNA from fetal liver–derived pro-B cells cultured in the presence of human interleukin 7 (IL-7), mouse stem cell factor (SCF), and human FLT3 ligand (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), from sorted B cells isolated from the spleen and bone marrow, or from AKXD27 tumors, was subjected to reverse transcription with the use of random primers and reverse transcriptase (Superscript; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was performed by means of the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche). For Evi3 reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR), the following primers were used: 4598792, 5′-TGGGGAGGCAGTAGACTG-3′, and 4598793, 5′-CTCCATCCTGGAGCCAGA-3′; or 4986355, 5′-CGTGGTCTCGCTGATCCT-3′, and 4986356, 5′-GCTTGTCACTATGCCTCTGTT-3′ (for long-terminal repeat/Evi3 [LTR/Evi3] transition RT-PCR). Conditions for Evi3 PCR were 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. ForEbfaz RT-PCR, the following primers were used: 5′-GCCCTGTGCCTCAAAGAGT-3′ and 5′-CCTTCCTCGATCATGTGGTT-3′. Conditions were as follows: 10 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 70°C for 1 minute, followed by 15 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 70°C for 1 minute, with an additional 5-second extension per cycle.

For Hprt RT-PCR, the following primers were used: 5′-GATACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GGTAGGCTGGCCTATAGGCT-3′. Conditions for Hprt PCR were 10 plus 15 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, with a 5-second extension per cycle in the last 15 cycles. Primers were from Integrated DNA Technologies.

ClustalW protein sequence alignment

Alignment of EVI3 and EBFAZ sequences were done by means of the ClustalW alignment feature in the MacVector 6.5.3 software package (Accelrys, Burlington, MA).

Subcellular localization

The full-length Evi3 open-reading frame (ORF), including the 5′ UTR and excluding the stop codon, was amplified from cloned cDNA by means of the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche) with the following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) (SalI and BamHI recognition sites are underlined): 4754821, 5′-AATTTTGTCGACAGTGATTACGTACAGAGCGAGT-3′, and 4944291, 5′-AAATAAGGATCCACTGCTGTGCTGAGTCATC-3′, and was cloned in frame with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) intoXhoI-BamHI–digested pEGFP-N3 (Clontech, BD Biosciences). The full-length Ebfaz ORF and 5′ UTR were amplified and cloned into XhoI-BamHI–digested pEGFP-N3 in a similar way, with the use of the following primers (SalI and BamHI sites are underlined): 5023709, 5′-AAAATAGTCGACCACGGGGGACCTCAGAA-3′; and 5052174, 5′-AAATAAGGATCCCTGTGCGTGCTGGCTCAT-3′. Conditions for PCR were 25 cycles of 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 5 minutes. Unmodified pEGFP-N3 plasmid was used as a control in transfection experiments.

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (HyClone, Logan, UT). On the day before transfection, 1 × 105 HeLa cells were seeded in 35-mm glass-bottom plates (MatTek, Ashland, MA). Cells were transfected with 0.4 μg EGFP, 0.4 μg EBFAZ/EGFP, or 0.8 μg EVI3/EGFP encoding plasmid, by means of Effectene (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 36 hours after transfection, the cells were analyzed by means of an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 135TV; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), and green fluorescence was detected by means of a fluorescein isothiocyanate–fluorescent filter set at 40 × magnification.

DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing was performed with primers from Integrated DNA Technologies and the PRISM BigDye cycle-sequencing kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). Sequencing reactions were analyzed by means of an ABI model 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, PerkinElmer).

GenBank submission

Results

Identification of an Evi3 candidate gene

BLAST searches of cloned Evi3 genomic sequences against the recently assembled mouse genomic sequence identified anEvi3 candidate gene that is located 125 kb downstream of the viral integrations at Evi3.4 No other genes mapping closer to Evi3 were identified in the BLAST search. This gene encodes a novel Krüppel-like zinc finger protein and is thus an excellent candidate for Evi3. Subsequently, by comparing a mouse Evi3 cDNA sequence (accession no.BC021376) with that of a human ortholog (accession no. AK027354), we were able to identify 3 more exons of this gene that were located 91.8 kb, 123.8 kb, and 124.9 kb upstream of the previously known coding region (Figure 1A). Addition of these 3 exons places the Evi3 integration sites within the transcription unit of this gene and further suggests that this is theEvi3 disease gene. The 8 exons encoding this gene are spread out over 280 kb of genomic DNA, which probably accounts for our previous difficulties in identifying this gene. The intron/exon structure of the mouse gene is well conserved with the human gene (data not shown). The mouse gene is located on chromosome 18, and the human ortholog in a syntenic region on chromosome 18q11.2.

Genomic structure of mouse

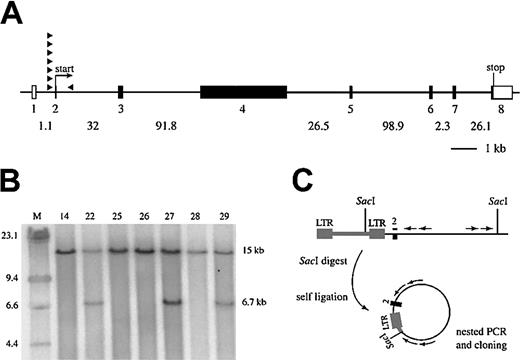

Evi3 and AKXD27 tumor analysis. (A) Genomic organization of Evi3. Exons are indicated as boxes; open boxes are 5′ or 3′ untranslated regions, whereas filled boxes are coding. Introns are indicated by lines between the exons, and intron sizes are given below. The exons are numbered below the boxes, and relative sizes of exons are drawn to scale. The sizes of the introns are not drawn to scale. The position of 8 retroviral integrations are depicted as filled arrowheads, with the arrow indicating the orientation relative to the Evi3 gene. (B) Southern blot analysis of SacI-digested genomic DNA from 7 AKXD27 tumors, hybridized with an Evi3-specific probe. A 15-kb germ line band is seen in all lanes, and a 6.7-kb band resulting from clonal viral integration is seen from tumors 22, 27, and 29. (C) Strategy for IPCR cloning of genomic sequence flanking the retroviral insertion sites, with the use of SacI-digested DNA and Evi3genomic nested primers (arrows).

Genomic structure of mouse

Evi3 and AKXD27 tumor analysis. (A) Genomic organization of Evi3. Exons are indicated as boxes; open boxes are 5′ or 3′ untranslated regions, whereas filled boxes are coding. Introns are indicated by lines between the exons, and intron sizes are given below. The exons are numbered below the boxes, and relative sizes of exons are drawn to scale. The sizes of the introns are not drawn to scale. The position of 8 retroviral integrations are depicted as filled arrowheads, with the arrow indicating the orientation relative to the Evi3 gene. (B) Southern blot analysis of SacI-digested genomic DNA from 7 AKXD27 tumors, hybridized with an Evi3-specific probe. A 15-kb germ line band is seen in all lanes, and a 6.7-kb band resulting from clonal viral integration is seen from tumors 22, 27, and 29. (C) Strategy for IPCR cloning of genomic sequence flanking the retroviral insertion sites, with the use of SacI-digested DNA and Evi3genomic nested primers (arrows).

Most viral integrations at Evi3 are located upstream of exon 2

RNA was not available from any of the previously analyzed AKXD tumors that contained viral integrations at Evi3. Therefore, to measure the effects of viral integration on expression of this gene, we screened 7 new AKXD27 B-cell lymphomas, for which RNA was available, by Southern blot analysis for evidence of viral integrations atEvi3. Three (43%) out of 7 of the AKXD27 lymphomas analyzed contained clonal viral integrations at Evi3 (Figure 1B). All 3 Evi3+ lymphomas contained one wild-type 15-kb allele and a mutant allele similar in size (approximately 6.7 kb). These results indicate that all 3Evi3 integrations are located within a very small genomic region, as reported previously for other integrations at the locus.6 Because of the clonality of these viral integrations, it is likely that retroviral integration atEvi3 is an early initiating event in the leukemic process.

The 3 retroviral integration sites at Evi3 were subsequently cloned by inverse PCR (IPCR) with the use of 2 nested sets ofEvi3 primers that were predicted to lie near the viral integration sites at Evi3 (Figure 1C). The IPCR products were then sequenced, and the data combined with data for another 5Evi3 integration site sequences published previously.4 Seven of the 8 integration sites map to a 30-bp region that is located immediately upstream of exon 2 (Figures1A,2B-C). This exon contains the predicted initiating ATG codon of the gene. All 7 integrations are in the same transcriptional orientation as the gene. The last integration in tumor 001a is located approximately 2 kb downstream of exon 2 and in the inverse orientation (Figure 1A and data not shown).

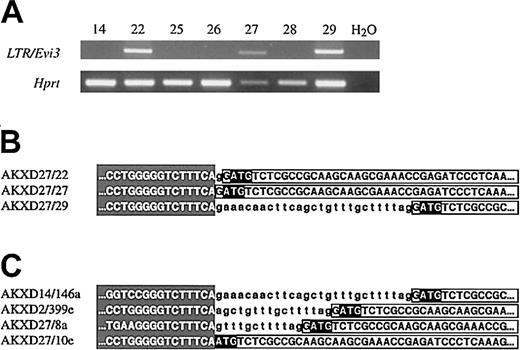

Retroviral integration results in 3′ LTR-promoted gene expression

Given the close proximity and the clustering of viral integrations at Evi3, we speculated that the 3′ viral LTR might be promoting expression of this gene, thus bypassing the endogenous promoter, presumably located upstream of exon 1. Using a primer located in the end of the 3′ LTR and a primer located in exon 4 of the gene (“Materials and methods”), we were able to amplify a band of the expected size from reverse-transcribed RNA of all 3Evi3+ AXKD27 tumors (tumors 22, 27, and 29) (Figure 2A). No amplification products were detected in tumors lacking integrations at Evi3 (Figure 2A), confirming that the LTR promotes expression of Evi3. The sequence of the 3 amplification products (Figure 2B) was identical to the genomic sequence from the IPCR clones except that exon 2 is spliced to exon 3, and exon 3 to exon 4. The 3′ LTR sequence is immediately followed either by intron 1 sequence and then exon 2 sequence or by exon 2 sequence (Figure 2B-C). The identity between IPCR product sequence and the sequence in the RT-PCR amplification products shows that the 3′ LTR directs the expression of Evi3, thus overriding the normal Evi3 promoter function. Furthermore, the predicted ATG-initiating codon located in exon 2 is retained in all 3 amplification products, suggesting that viral integration promotes the expression of a wild-type protein. Part of the previously cloned genomic sequence from the other 4 integrations upstream of exon 2 are depicted in Figure 2C.4 As can be seen, these integration sites are located in the same 30-nucleotide area immediately upstream of exon 2 as is the case for the 3 novel AKXD27 integration sites. The similarity to the sequence from the RT-PCR amplification products in Figure 2B suggests that the 3′ LTR also directed expression of Evi3 in these tumors. Unfortunately, we are not able to test this directly, since there is no RNA available from these tumors.

The 3′ LTR-driven expression of

Evi3. (A) RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the 7 AKXD27 tumors. One primer is located in the 3′ LTR sequence, and the other in exon 4 of Evi3. Hprt primers were included as a control for reverse transcription (lower panel). (B) Part of the sequence from the amplification products in panel A, showing the transition between LTR (shading) and intron 1 (small letters) and/or exon 2 (boxed capital letters). The ATG start codon is in reverse boldface. The RT-PCR sequence is identical to the sequence cloned by IPCR except that the RT-PCR product lacks introns 2 and 3. (C) Genomic sequence data from 4 previously cloned Evi3 integrations, showing the LTR/intron/exon transitions.

The 3′ LTR-driven expression of

Evi3. (A) RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the 7 AKXD27 tumors. One primer is located in the 3′ LTR sequence, and the other in exon 4 of Evi3. Hprt primers were included as a control for reverse transcription (lower panel). (B) Part of the sequence from the amplification products in panel A, showing the transition between LTR (shading) and intron 1 (small letters) and/or exon 2 (boxed capital letters). The ATG start codon is in reverse boldface. The RT-PCR sequence is identical to the sequence cloned by IPCR except that the RT-PCR product lacks introns 2 and 3. (C) Genomic sequence data from 4 previously cloned Evi3 integrations, showing the LTR/intron/exon transitions.

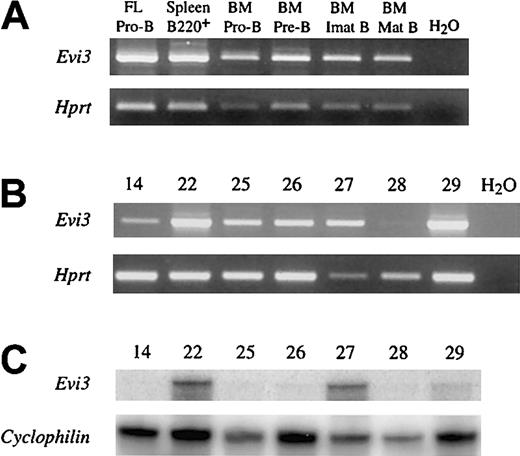

Viral integration up-regulates gene expression

To determine whether viral integration up-regulates expression of this gene in cells that already express it or turns on de novo expression of the gene in cells that do not normally express it, we examined the expression pattern of this gene during B-cell development by RT-PCR of FACS-sorted cells and pro-B cells derived from fetal liver. As shown in Figure 3A, all B-cell subsets analyzed express the gene. This includes pro-B cells derived from fetal liver, B220+ splenocytes, and pro-B, pre-B, and immature and mature B cells isolated from bone marrow. This gene is also expressed in AKXD27 B-cell lymphomas that do not have viral integrations at Evi3 (Figure 3B). These results suggest that viral integration at Evi3 up-regulates expression of this gene, which is normally expressed in B cells.

Evi3 expression in AKXD27 tumors and normal B cells.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of normal Evi3 expression in different B-cell subsets (upper panel). Exon 3 and exon 4 primers were used. FL indicates fetal liver; BM, bone marrow. Pro-B indicates IgM−IgD−CD43+B220+cells; Pre-B, IgM−IgD−CD43−B220+cells; Imat B (immature B), IgM+IgD− cells; Mat B (mature B), IgM+IgD+ cells. Lower panel shows the result from using Hprt control primers. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Evi3 expression in the 7 AKXD27 tumors. Upper panel shows the results from RT-PCR with 2 Evi3 primers as in panel A. The lower panel shows the results of RT-PCR withHprt control primers. (C) RNase-protection analysis of RNA from the 7 AKXD27 tumors with an Evi3-specific probe (upper panel) or an internal control probe (Cyclophilin, lower panel). For clarity, only the protected bands are shown.

Evi3 expression in AKXD27 tumors and normal B cells.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of normal Evi3 expression in different B-cell subsets (upper panel). Exon 3 and exon 4 primers were used. FL indicates fetal liver; BM, bone marrow. Pro-B indicates IgM−IgD−CD43+B220+cells; Pre-B, IgM−IgD−CD43−B220+cells; Imat B (immature B), IgM+IgD− cells; Mat B (mature B), IgM+IgD+ cells. Lower panel shows the result from using Hprt control primers. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Evi3 expression in the 7 AKXD27 tumors. Upper panel shows the results from RT-PCR with 2 Evi3 primers as in panel A. The lower panel shows the results of RT-PCR withHprt control primers. (C) RNase-protection analysis of RNA from the 7 AKXD27 tumors with an Evi3-specific probe (upper panel) or an internal control probe (Cyclophilin, lower panel). For clarity, only the protected bands are shown.

To determine whether this is indeed the case, we quantitated the expression of this gene by using RNase protection. When compared with aCyclophillin internal control, all 3Evi3+ AKXD27 lymphomas contained significantly more Evi3 transcripts than did lymphomas without viral integrations at Evi3 (Figure 3C). These results confirm that viral integration at Evi3 up-regulates expression of this gene. On the basis of these data and the striking homology of this gene to Ebfaz (to be discussed in the next section), we conclude that we have identified the correct gene, which will subsequently be referred to simply as Evi3.

Evi3 shows striking homology to Ebfaz

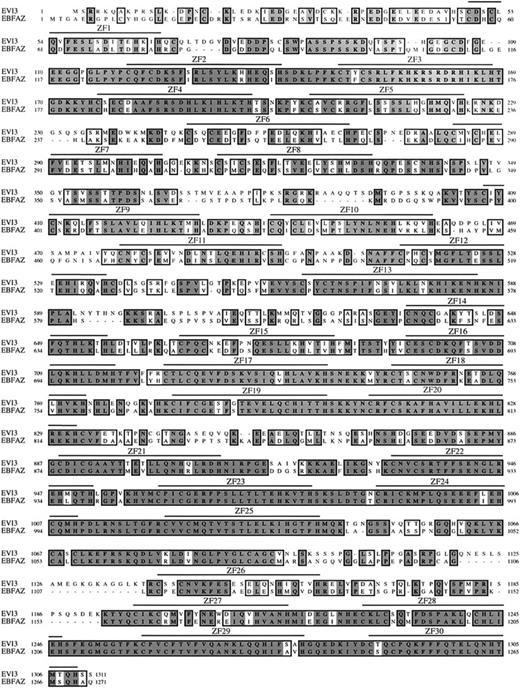

Comparison of a mouse Evi3 cDNA sequence (accession no.BC021376) against GenBank showed that Evi3 has striking homology to the early B-cell factor–associated zinc finger gene (Ebfaz, also known as the olfactory 1–associated zinc finger gene Oaz).7,8 We next cloned full-lengthEvi3 and Ebfaz cDNA from a mouse spleen library, followed by sequencing. All 30 zinc fingers identified in EVI3 are conserved in mouse and human EBFAZ. A comparison of the mouse EVI3- and EBFAZ-encoded proteins is shown in Figure4. The 2 proteins are 62% identical and 74% similar at the amino acid level. All 30 zinc fingers identified in both proteins conform to the consensus sequence for Krüppel-like zinc fingers, C-X2-4-C-X3-F-X5-L-X2-H-X2-4-H, where X is any residue.9 Even the amino acids in between the critical residues required for zinc finger function are conserved in many of the fingers. According to our analysis, the proteins do not contain any other known protein domains. So far, EVI3 is the only other protein besides EBFAZ that contains 30 zinc fingers, and these 2 proteins therefore probably belong to a novel subfamily of Krüppel-like zinc finger proteins. EVI3 and EBFAZ are also highly related (more than 90%) to their respective human orthologs (data not shown), indicating that strong evolutionary pressure has maintained the overall structure and function of these 2 proteins.

ClustalW alignment of EVI3 and EBFAZ protein sequences.

Identities or similarities are boxed; identities are dark shaded and similarities are light shaded. The positions of the conserved 30 zinc fingers, from the first cysteine to the last histidine, are indicated above the sequence (ZF1-ZF30).

ClustalW alignment of EVI3 and EBFAZ protein sequences.

Identities or similarities are boxed; identities are dark shaded and similarities are light shaded. The positions of the conserved 30 zinc fingers, from the first cysteine to the last histidine, are indicated above the sequence (ZF1-ZF30).

Ebfaz is not expressed in B cells

To determine the expression pattern of Evi3 andEbfaz, we examined the expression of these genes in several different adult tissues by polyA Northern blot analysis. Because of the high degree of nucleotide sequence conservation between these genes, we used relatively nonhomologous 3′ UTR fragments as probes (“Materials and methods”). As shown in Figure 5A, 2Evi3 transcripts, 5 kb and 6 kb in size, were detected in all adult tissues examined. The 5-kb transcript is more prominent than the 6-kb transcript and corresponds to the size expected from cDNA sequencing (4.9 kb). The 6-kb transcript probably originates from the use of a second polyA addition site that is located 1 kb downstream from the polyA addition site used in the 5-kb message (data not shown). A 3-kb transcript was also seen in testis, but the significance of this transcript is unknown since testis is known to produce aberrant transcripts (data not shown). Evi3 expression is highest in the heart and brain, followed by lung, skin, and spleen.

PolyA Northern blot analysis of

Evi3 and Ebfaz expression and Ebfaz RT-PCR. (A) Upper panel shows the results from Northern hybridization with a 3′ UTR Evi3probe. Middle panel shows the results from hybridization with a 3′ UTREbfaz probe. The lower panel shows Gapdexpression. B indicates brain; H, heart; K, kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; M, muscle; Sk, skin; Si, small intestine; Sp, spleen; St, stomach; Te, testis; and Th, thymus. (B) Upper panel shows RT-PCR analysis of Ebfaz expression. One primer was inEbfaz exon 3, and the other was at the transition between exons 4 and 5. F Brain indicates fetal brain; FL, fetal liver; BM, bone marrow; Pro-B, IgM−IgD−CD43+B220+cells; Pre-B, IgM−IgD−CD43−B220+cells; Imat B (immature B), IgM+IgD− cells; and Mat B (mature B), IgM+IgD+ cells. Lower panel shows the result from using Hprt control primers.

PolyA Northern blot analysis of

Evi3 and Ebfaz expression and Ebfaz RT-PCR. (A) Upper panel shows the results from Northern hybridization with a 3′ UTR Evi3probe. Middle panel shows the results from hybridization with a 3′ UTREbfaz probe. The lower panel shows Gapdexpression. B indicates brain; H, heart; K, kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; M, muscle; Sk, skin; Si, small intestine; Sp, spleen; St, stomach; Te, testis; and Th, thymus. (B) Upper panel shows RT-PCR analysis of Ebfaz expression. One primer was inEbfaz exon 3, and the other was at the transition between exons 4 and 5. F Brain indicates fetal brain; FL, fetal liver; BM, bone marrow; Pro-B, IgM−IgD−CD43+B220+cells; Pre-B, IgM−IgD−CD43−B220+cells; Imat B (immature B), IgM+IgD− cells; and Mat B (mature B), IgM+IgD+ cells. Lower panel shows the result from using Hprt control primers.

Two Ebfaz transcripts were also detected on the Northern blot (Figure 5A). Interestingly, these transcripts are the same size as the 2 Evi3 transcripts except in the case ofEbfaz, where the 6-kb transcript is the most prominent. A 1-kb transcript was also seen in testes (not shown). Ebfaz expression is highest in brain, corresponding well with its original identification from olfactory tissue.7 Otherwise, the expression pattern ofEbfaz follows that of Evi3. We also measured the expression level of these genes using RNase protection, which showed that the expression level of these genes is similar in most tissues (data not shown). Both genes are generally expressed at low levels, however, as the messages were only detectable after several days of exposure.

As shown in Figure 3A, Evi3 is expressed in all B-cell stages studied, and both Evi3 and Ebfaz are expressed in the spleen (Figure 5A). Since Ebfaz was identified as an interaction partner of olfactory-1/early B-cell factor (OLF1/EBF),7 we next wanted to study the expression ofEbfaz in sorted B cells. Much to our surprise, as seen in Figure 5B, we could not detect Ebfaz expression in any B-cell type analyzed, whereas Ebfaz expression was readily detected in fetal brain, as expected. These results indicate that EVI3, not EBFAZ, is the likely interaction partner of EBF in B cells.

EVI3 is a nuclear protein

Human EBFAZ is a nuclear protein.8 To determine whether EVI3 is also a nuclear protein, the EVI3 open reading frame (ORF), including the 5′ UTR and presumed Kozak initiation sequence,10 was fused in frame to the ORF of the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), creating a fusion protein with EVI3 sequences at the N-terminus and EGFP sequences at the C-terminus. A construct expressing this fusion protein was then transfected into HeLa cells, and the cells were examined for GFP expression. As controls, HeLa cells were also transfected with a construct expressing a murine EBFAZ/EGFP fusion protein or EGFP protein alone. As shown in Figure 6, HeLa cells transfected with the EGFP construct are fluorescent throughout the cell, while fluorescence is restricted to the nucleus of cells transfected with the EVI3/EGFP– or EBFAZ/EGFP–encoding fusion constructs. Therefore, EVI3, like the murine and human EBFAZ proteins, is located in the nucleus as would be expected for a protein with 30 zinc fingers. These results also show that the cloned cDNAs for both proteins include a complete ORF as well as all of the signals necessary for the initiation of translation.

Nuclear localization of EVI3 and EBFAZ fusion proteins.

Upper panel: UV microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with constructs encoding EGFP, EVI3/EGFP, or EBFAZ/EGFP. Lower panel: the same cells seen in phase-contrast microscopy. Original magnification is × 40.

Nuclear localization of EVI3 and EBFAZ fusion proteins.

Upper panel: UV microscopy of HeLa cells transfected with constructs encoding EGFP, EVI3/EGFP, or EBFAZ/EGFP. Lower panel: the same cells seen in phase-contrast microscopy. Original magnification is × 40.

Discussion

Here we show that viral integrations at Evi3up-regulate the expression of a novel Krüppel-like zinc finger protein via 3′ LTR-directed promoter insertion. EVI3 has high homology with EBFAZ, a multifunctional protein that participates in many signaling pathways via its multiple zinc fingers.8

EBFAZ was originally identified by its ability to associate with OLF1/EBF in a yeast 2-hybrid screen.7 EBFAZ abolishes EBF-mediated transactivation of native promoters located upstream of the olfactory marker protein (Omp) and type III adenylyl cyclase (Adcy3) genes by sequestering EBF proteins in a heteromultimeric complex, which fails to bind the EBF-binding site. EBFAZ binds EBF by way of fingers 28 through 30.11 EBFAZ also binds DNA by way of fingers 2 through 8, as either a homodimer or a heterodimer with EBF. The EBFAZ DNA-binding site bears close resemblance to the specificity protein–1 (SP1) recognition sequence, which has been shown to confer EBF-mediated reporter activation in a cell-line–based assay. EBFAZ is thus a complex protein that uses one set of zinc fingers to bind DNA and another set for protein dimerization.

Even though Ebfaz was originally cloned as an OLF1/EBF–interacting partner, the expression of Ebfaz in B cells has never been demonstrated. We show that Ebfaz is not expressed in B cells, whereas Evi3 is expressed in all B-cell stages analyzed, indicating that EVI3, and not EBFAZ, is the EBF-interacting partner in B cells. All zinc fingers present in EBFAZ are conserved in EVI3, including those important for its interaction with EBF.

The initiation of B-lymphopoiesis in the bone marrow depends on EBF as well as another transcription factor, transcription factor E2A (TCFE2A; reviewed in Schebesta et al12). In the absence of either protein, B-cell development is arrested at a very early stage, before DH-JH rearrangements at theIgh locus have taken place. TCFE2A induces the expression of EBF, which in concert with TCFE2A induces the expression of many B-cell–specific genes. The mere activation of the B-cell–specific gene-expression program is not sufficient, however, to commit B-cell progenitors to the B-lymphoid lineage in the absence of paired box–5 (PAX5). PAX5 restricts the developmental options of lymphoid progenitors to the B-cell pathway by repressing lineage-inappropriate genes and simultaneously activating a number of B-cell–specific genes.13 Consistent with the function of these genes in B-cell lineage commitment, Tcf2ea mutant mice lack B cells14,15; Ebf mutant mice contain B220+CD43+ progenitor B cells that have unrearranged DH and JH gene segments16; and Pax5 mutant mice contain B cells that are blocked at an early pro-B-cell stage.17

Evi3 and Ebfaz are coexpressed in most adult tissues, except for B cells. EVI3 and EBFAZ proteins are also both located in the nucleus. Deregulated expression of EVI3 might induce B-cell lymphoma by binding to and inhibiting EBF activity in B cells in a manner analogous to what has been described for EBFAZ,7 resulting in a block in B-cell differentiation. This hypothesis is consistent with previous results showing that viral integrations at Evi3 are more common in pre-B-cell lymphomas than in more mature B-cell lymphomas.6 Our failure to find viral integrations near Ebf in AKXD B-cell lymphomas, despite our ability to identify viral integrations near several other genes involved in B-cell differentiation and lineage commitment (ie, Tcfe2a, Pax5, Notch1, Notch2, Prdm1, Hes1, Dtx2, Id3, and Lfng),4 could be explained if the effects of EVI3 overexpression and EBF down-regulation on B-cell differentiation are the same.

It has been shown that EBFAZ can also bind to SMA- and MAD-related protein–1 (SMAD1) and SMAD4 in response to bone morphogenetic protein–2 (BMP2) signaling.8 EBFAZ, SMAD1, and SMAD4 then synergistically bind to the BMP response element (BRE) and activate the Xvent2 promoter. EBFAZ fingers 9 through 13 mediate BRE binding, while fingers 14 through 19 mediate SMAD binding. The region of EBFAZ that binds EBF (fingers 28 through 30) is dispensable for BMP signaling, and the ability of EBFAZ to act as a transcriptional partner of EBF can be inhibited by BMP2 in a SMAD-dependent manner. Fingers 9 through 13 and 14 through 19 are well conserved in EVI3, and it is therefore possible that EVI3 also participates in BMP signaling. In addition, EBFAZ binds DNA as a homodimer through fingers 2 through 8, and it is possible that EVI3 can also bind DNA as a homodimer through fingers 2 through 8. Deregulation of this DNA-binding activity might also contribute to the ability of EVI3 to induce B-cell disease.

We thank Dr Yang Du for B220+ splenocyte reverse-transcribed RNA and Linda S. Cleveland for technical assistance with DNA sequencing.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 17, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2652.

Supported by the National Cancer Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services; the Danish Natural Science Research Council (S.W.); the Danish Medical Research Council (S.W.); and the Danish Natural Science Research Council (S.L.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Neal G. Copeland, Mouse Cancer Genetics Program, Bldg 539, Rm 229, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD 21702-1201; e-mail: copeland@ncifcrf.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal