Preemptive ganciclovir therapy has reduced the occurrence of early cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease after hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation. However, late disease is increasingly reported. We describe 2 patients who developed late CMV central nervous system (CNS) disease after haploidentical HSC transplantation. Direct genotypic analysis was used to examine the presence of ganciclovir resistance. One patient had a mixed viral population in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), with coexistent wild-type and mutantUL97 sequences. The presence of 2 different strains was confirmed by subclone sequencing of the UL54 gene. One of the strains was different from the concurrent blood strain. The second patient had resistant variant in the lungs. These cases raise concern about the changing natural history of CMV disease in HSC transplantation, with emergence of previously uncommon manifestations following prolonged prophylaxis. Under these circumstances the CNS may be a sanctuary site, where viral persistence and antiviral drug resistance could result from limited drug penetration.

Introduction

Despite the availability of potent antiviral drugs, cytomegalovirus (CMV) remains a significant complication after hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation.1 The widespread use of prophylactic and preemptive ganciclovir therapy has reduced the occurrence of early CMV disease; however the development of late disease is increasingly recognized.2 3

Prolonged ganciclovir exposure may also lead to the selection of ganciclovir-resistant strains.4,5 Ganciclovir resistance results mainly from impaired phosphorylation of the drug, caused by mutations in the CMV UL97phosphotransferase.5-8 Less frequently, resistance is caused by mutations in the UL54 (DNA polymerase) gene.9 10

Until recently, ganciclovir resistance has been described mainly among AIDS patients receiving prolonged maintenance therapy.4,7,11 Over the past few years, ganciclovir resistance has been increasingly reported among solid-organ transplant recipients, especially those with high viral load and lengthened antiviral exposure.12,13 Thus far, there have been only anecdotal reports of ganciclovir resistance among hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients.14 We and others have described the emergence of ganciclovir resistance in children after HSC transplantation.15,16 Studies in adult HSCT recipients, however, demonstrated the absence of resistance after up to 56 days of cumulative ganciclovir exposure.17 Yet, with improved survival after HSC transplantation, change in immunosuppressive regimens, and longer duration of ganciclovir exposure, drug resistance in association with late disease is expected to become a growing problem in this setting. Here, we report 2 cases of late-onset CMV central nervous system (CNS) disease, which developed during preemptive antiviral therapy after HSC transplantation. Direct genotypic analysis was used to examine the role of drug resistance and compartmental differences among infecting strains in the development of this unusual manifestation.

Study design

Patients

The 2 patients were treated at the Rambam Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, where a total of 138 patients received allogeneic HSCT (28 of which were haploidentical) between January 1999 and January 2002. After transplantation, the patients received antiviral therapy with acyclovir and were monitored for CMV infection by weekly pp65 antigenemia assay. Preemptive ganciclovir therapy was instituted on positive antigenemia result. Treatment was switched to foscarnet when clinical resistance was suspected or when adverse effects necessitated discontinuation of ganciclovir. Approval was obtained from the Rambam institutional review board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient 1.

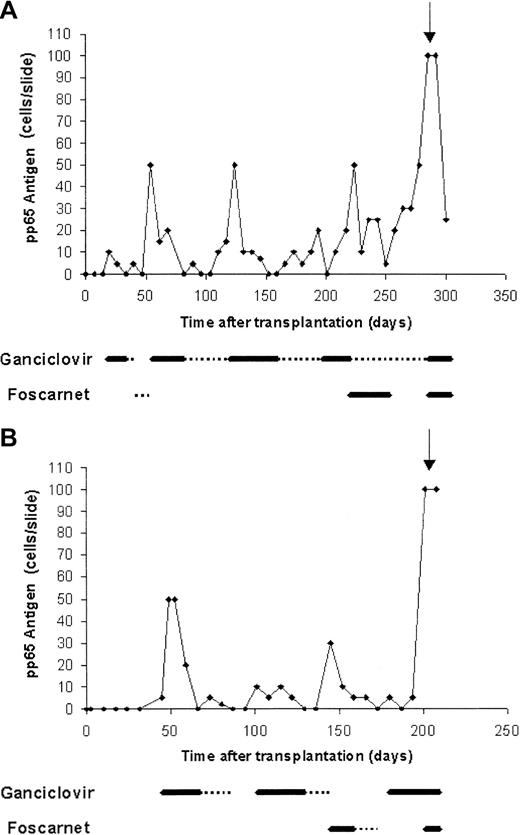

A 30-year-old woman with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) diagnosed 1.5 year previously (M2 t(6;9), second complete remission) received haploidentical T-cell–depleted HSCT from her sister. Both patient and donor were CMV seropositive (D+/R+). Conditioning regimen included total body irradiation, thiotepa, fludarabine, and antithymocytic globulin. Her initial transplantation course was unremarkable. Starting from day 19, recurrent episodes of CMV reactivation were noted, which were treated by preemptive therapy (Figure 1A). Her subsequent course was further complicated by chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) treated with steroids and lymphopenia (CD4 30 cells/mm3). On day 285, the patient presented with acute confusional state. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for CMV, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed diffuse white matter changes. The patient subsequently developed disseminated disease with CMV pneumonitis and died despite combined treatment with ganciclovir, foscarnet, and anti-CMV immunoglobulins.

Recurrent CMV reactivation in patients who developed late-onset CMV disease following preemptive therapy.

(A, patient 1; B, patient 2) Thick line, induction treatment; dotted line, maintenance treatment; arrow, time of diagnosis of disease.

Recurrent CMV reactivation in patients who developed late-onset CMV disease following preemptive therapy.

(A, patient 1; B, patient 2) Thick line, induction treatment; dotted line, maintenance treatment; arrow, time of diagnosis of disease.

Patient 2.

A 54-year-old man with AML diagnosed 3 months previously (M2; monosomy 7, first complete remission) received haploidentical T-cell–depleted HSCT from his daughter. CMV serostatus was D−/R−. Conditioning regimen included thiotepa, fludarabine, and melphalan. During the neutropenic period, the patient received granulocyte infusion from CMV-seropositive donor because of severe life-threatening perianal abscess. His subsequent course was characterized by recurrent episodes of CMV infection, starting from day 45 (Figure 1B). Severe GVHD developed from day 140. On day 201, low-grade fever developed with confusion and disorientation. CSF PCR was positive for CMV. CMV pneumonitis was also evident. The patient was treated with ganciclovir and foscarnet but died shortly thereafter.

Amplification and sequencing of the CMV UL97 andUL54 genes

Direct PCR sequencing was performed as described7,10 15 by using overlapping primer pairs encompassing nucleotides 1207 to 1979 (UL97) and 900 to 3000(UL54). These regions include all of the known resistance mutations.

For subclone sequencing, PCR products were inserted into p-Gem-T vector, transformed into Escherichia coli DH-5α, and both strands of the inserts were sequenced.

Results and discussion

CMV CNS disease had been exceedingly rare in HSCT recipients in the era that predated the use of preventive antiviral therapy. In patients with advanced AIDS, CMV CNS disease often develops during therapy for human CMV (HCMV) retinitis and can result from ganciclovir-resistant strains.18 19 The development of late disease after cumulative ganciclovir therapy of 252 and 103 days suggested the presence of resistant virus. Indeed, direct genotypic analysis revealed the presence of viral strains with UL97 ganciclovir-resistance mutations in the blood and CNS in patient 1 and in the lungs in patient 2 (Table 1). The amino acid substitutions found in the UL54 gene were not associated with resistance.

CMV UL97 and UL54 amino acid substitutions in HSCT recipients with late-onset CMV disease

| Specimen . | Days after HSCT . | Cumulative gan/fos, d . | Specimen type . | UL97 amino acid substitution . | UL54amino acid substitution . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | |||||

| A | 54 | 21/14 | Blood | WT | — |

| B | 131 | 98/14 | Blood | WT | — |

| C | 264 | 231/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe*; WT | — |

| D | 278 | 245/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe*; WT | — |

| E | 285 | 252/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe* | WT Pro628Leu, Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Ser, 885T insertion |

| F | CSF | Cys603Trp*; WT | WT strain 1: Pro628Leu, Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Ser, 885T insertion (same sequence as E above). Strain 2 (partial sequence): 16 nucleotide differences, no amino acid differences from strain 1 | ||

| Patient 2 | |||||

| A | 52 | 3/0 | Blood | WT | — |

| B | 145 | 82/0 | Blood | WT | — |

| C | 201 | 103/28 | Blood | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| D | 204 | 106/31 | BAL | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| E | 205 | 107/32 | CSF | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| F | 212 | 114/39 | Lung biopsy | Cys592Gly*; WT | WT Ser655Ley, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| Specimen . | Days after HSCT . | Cumulative gan/fos, d . | Specimen type . | UL97 amino acid substitution . | UL54amino acid substitution . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | |||||

| A | 54 | 21/14 | Blood | WT | — |

| B | 131 | 98/14 | Blood | WT | — |

| C | 264 | 231/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe*; WT | — |

| D | 278 | 245/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe*; WT | — |

| E | 285 | 252/40 | Blood | Leu595Phe* | WT Pro628Leu, Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Ser, 885T insertion |

| F | CSF | Cys603Trp*; WT | WT strain 1: Pro628Leu, Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Ser, 885T insertion (same sequence as E above). Strain 2 (partial sequence): 16 nucleotide differences, no amino acid differences from strain 1 | ||

| Patient 2 | |||||

| A | 52 | 3/0 | Blood | WT | — |

| B | 145 | 82/0 | Blood | WT | — |

| C | 201 | 103/28 | Blood | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| D | 204 | 106/31 | BAL | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| E | 205 | 107/32 | CSF | WT | WT Ser655Leu, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

| F | 212 | 114/39 | Lung biopsy | Cys592Gly*; WT | WT Ser655Ley, Asn685Ser, Ala885Thr, Asn898Asp |

gan indicates ganciclovir; fos, foscarnet; WT, wild-type sequences; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; and —, not available.

Amino acid substitutions known to be associated with resistance.

Potential risk factors for late disease with ganciclovir resistance were haploidentical T-cell–depleted HSCT with myeloablative conditioning. Delayed immune reconstitution together with GVHD in these patients could allow for continuous high-rate virus replication (as reflected by the antigenemia) with emergence of resistant strains under drug pressure. Notably, similar underlying factors were identified in a recent series of HSCT recipients who developed HCMV retinitis—another uncommon manifestation.20 Thus, the shift in the epidemiology of CMV in HSCT recipients to late-onset disease may be associated with the emergence of unusual manifestations, previously considered characteristic of AIDS patients.

The pathogenesis of late CMV CNS disease after HSC transplantation is not clear. The virus may have migrated to the brain during preceding episodes of viremia. Interestingly, direct sequencing revealed the presence of mixed viral sequences in the CSF of patient 1, with different resistance mutations in the blood and CSF. To determine the number of strains represented, we subcloned the UL54 product (nucleotides 2400 to 3000). The results showed the presence of at least 2 different strains in the CNS, one of which was different from the concurrent blood strain by 16 nucleotides. The CMV serostatus of patient 1 was D+/R+. Thus, there are 2 identifiable sources for multiple circulating strains. The serostatus of patient 2 was D−/R−, which points to a single source of virus from granulocyte infusion.

The finding of different strains in the blood and CNS raises the possibility of a unique mechanism for CNS disease in HSCT recipients: recent studies of gene delivery to the brain have shown that after bone marrow (BM) transplantation, donor-derived BM cells repopulate the CNS with subsequent differentiation into microglia, neurons, and astrocytes.21-23 Because BM progenitor cells are a major reservoir of latent CMV,24 the CNS could potentially become an acquired site of CMV latency in HSCT recipients. Low penetration of antiviral drugs to the CNS, along with impaired local immune surveillance, may favor persistent replication with possible emergence of resistant strains.

As demonstrated in AIDS patients, the presence of multiple strains may be associated with more severe disease.25 Compartmental differences among infecting strains, found in the 2 patients, suggest that direct genotypic analysis in the blood may not always predict the resistance profile in the tissues.

In conclusion, the cases described herein raise concern about the changing natural history of HCMV disease in HSC transplantation. Under these circumstances, the CNS may become a viral sanctuary site. New antiviral agents with different mechanisms and better penetration are needed to deal with the emergence of late-onset drug-resistant CMV in HSCT recipients.

The work was carried out in the Straus Molecular Diagnostics Core Facility, Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, Israel.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 22, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1982.

Supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation and Israel Cancer Association, and a grant from the Samuel and Dora Straus Foundation, New York, NY.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Dana G. Wolf, Department of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, Hadassah University Hospital, POB 12000, Jerusalem, Israel 91120; e-mail:wolfd@md2.huji.ac.il.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal