Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X-linked disease characterized by thrombocytopenia, eczema, and various degrees of immune deficiency. Carriers of mutated WASP have nonrandom X chromosome inactivation in their blood cells and are disease-free. We report data on a 14-month-old girl with a history of WAS in her family who presented with thrombocytopenia, small platelets, and immunologic dysfunction. Sequencing of the WASP gene showed that the patient was heterozygous for the splice site mutation previously found in one of her relatives with WAS. Sequencing of all WASP exons revealed no other mutation. Levels of WASP in blood mononuclear cells were 60% of normal. Flow cytometry after intracellular staining of peripheral blood mononuclear cells with WASP monoclonal antibody revealed both WASPbright and WASPdimpopulations. X chromosome inactivation in the patient's blood cells was found to be random, demonstrating that both maternal and paternal active X chromosomes are present. These findings indicate that the female patient has a defect in the mechanisms that lead in disease-free WAS carriers to preferential survival/proliferation of cells bearing the active wild-type X chromosome. Whereas the patient's lymphocytes are skewed toward WASPbright cells, about 65% of her monocytes and the majority of her B cells (CD19+) are WASPdim. Her naive T cells (CD3+CD45RA+) include WASPbrightand WASPdim populations, but her memory T cells (CD3+CD45RA−) are all WASPbright. After activation in vitro of T cells, all cells exhibited CD3+CD45RA− phenotype and most were WASPbright with active paternal (wild-type) X chromosome, suggesting selection against the mutated WASP allele during terminal T-cell maturation/differentiation.

Introduction

Wiskott was the first to describe male individuals from a single family with thrombocytopenia, eczema, and bloody diarrhea in 1937.1 In 1954, Aldrich established X-linked inheritance of the disease.2 Subsequently the disease was called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS). In its fully expressed form, boys affected with WAS present at an early age with severe thrombocytopenia, eczema, and various degrees of immunodeficiency. Profound thrombocytopenia with small platelets is present in all patients. Clinical classification is based on severity of eczema and immunodeficiency.3 Severe cases are additionally characterized by higher incidences of autoimmune and lymphoproliferative diseases.4-6 The primarily affected cells in WAS patients are lymphocytes and platelets. Both cellular and humoral immunity are impaired. Defects include deficient response of lymphocytes to mitogens and decreased levels of IgG and IgM.7 In addition, antibody titers to polysaccharides are often depressed.8-11 The profoundly decreased platelet number and small size are due mainly to destructive events occurring in the circulation.12-14

The gene, mutations of which are responsible for the phenotype, was mapped to Xp11.23 and consists of 12 exons encoding a protein of 502 amino acids (WASP).15,16 WASP is expressed solely in blood cells; it is a multidomain protein that participates in cytoskeleton reorganization17 (for a review, see Higgs and Pollard18).

The severity of immune disease in WAS patients correlates in many cases with specific mutations and with the level of WASP in blood cells. Whereas patients with severe disease frequently lack detectable WASP in blood cells, most patients with mild disease have measurable levels of WASP in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).19-22

Females who are carriers of a defective WASP gene are usually asymptomatic. Their mature blood cells demonstrate a nonrandom pattern of X chromosome inactivation with the chromosome bearing the normal WASP gene active in most cells.23-28Levels of WASP in carrier PBMCs are indistinguishable from those in unaffected individuals.

In this report we describe a female patient who presented with symptoms resembling the WAS phenotype. The patient was heterozygous for aWASP mutation and had a random pattern of X chromosome inactivation in her PBMCs. WASP expression levels in the patient's PBMCs were lower than normal, but substantially higher than those in WAS patients, in agreement with the presence of WASP in some of her lymphocytes and monocytes.

Patients, materials, and methods

Blood cells

Whole blood from the female patient, family members, and unaffected control individuals was collected in acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD; National Institutes of Health [NIH] formula A) and fractionated immediately or after overnight shipment at ambient temperature. Blood samples were collected also from patients with diagnosed WAS and in parallel from healthy consenting control subjects under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Center for Blood Research. The blood was centrifuged at 200g for 12 minutes to separate platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and pelleted cells. PRP was centrifuged at 800g for 15 minutes, and the pelleted platelets were washed once in platelet buffer (10 mM TES [Tris-hydroxymethyl-methyl-2-aminoethane sulphonic acid] buffer, pH 7.2, 136 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% glucose, 0,1% bovine albumin).22 Packed blood cells remaining after removal of PRP were combined with an equal volume of 2% dextran in 150 mM NaCl for 30 to 40 minutes at approximately 22°C to sediment erythrocytes. The supernatant was aspirated, and the leukocytes were fractionated by centrifugation on Histopaque 1077 (Sigma, St Louis, MO). PBMCs collected from the interface layer were washed with Ca++Mg++-free Hanks balanced salt solution by pelleting at 200g for 15 minutes.

Platelet sizing

Platelet sizing was determined on PRP obtained by gravity sedimentation of blood cells from aliquots of ACD-anticoagulated blood. Using an Elzone Particle Analyzer Model 112 (Particle Data Group, Elmhurst, IL), the size of the platelets was measured relative to standardized latex spheres.29

Western blots

Lysates were prepared of PBMCs at 15 × 106/mL in sodium dodecyl sulfate containing the protease inhibitors diisopropylfluorophosphate (2 mM) and leupeptin (25 μg/mL; Sigma) as described.22 The lysates were electrophoresed under reducing conditions and the proteins transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA) for staining with 100 ng/mL affinity-purified rabbit antibodies to WASP C-terminal peptide (W-485) as described.22 The reactive bands were detected by 125I-labeled secondary antibodies and quantified with the Phosphorimager Storm 860 Imager and Image Quant v 1.1 program (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

DNA analysis

To detect WASP mutations, the 12 exons were amplified together with flanking intron regions.30 The DNA genomic template was isolated from whole blood. The amplicons were sequenced on a PE Biosystems Model 377 automatic sequencer at the Sequencing Facility of the Biopolymers Laboratory, BCMP, Harvard Medical School.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

RNA was isolated from PBMCs using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) as recommended by the manufacturer. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized by incubating 2 μg total RNA with oligodT (Promega, Madison, WI) as primer using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (RT; Gibco). Then, 4 μL cDNA was used to amplify nucleotides 2 through 1083 of WASP mRNA with primers W-2 and 5.24 (1 μM each)31 in 2 mM Mg2SO4, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 2.5 U platinum Taq high-fidelity polymerase (Gibco BRL). The reaction was preincubated at 94°C for 2 minutes followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 57°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute. Additional extension was at 72°C for 10 minutes. Products were purified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

X chromosome inactivation

The gDNA was isolated from PBMCs. After restriction digestion with either RsaI and HpaII or RsaI only, gDNA fragments were amplified using primers flanking methylation-sensitive restriction sites in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene.28 32 Amplified products were fractionated by electrophoresis on nondenaturing gels and detected by silver stain.

Antibodies

The monoclonal antibody (mAb) 5A5, which was kindly provided by Dr Shigeru Tsuchiya and Dr Shin Kawai (Department of Pediatric Oncology, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan), was generated by immunizing mice with WASP amino acids 1-320.33 The mAb 5A5 stained WASP but not N-WASP on Western blots and did not cross-react with N-WASP.33 The epitope recognized by 5A5 was localized to amino acids 146-265. WASP antibody W-485 was raised in rabbits immunized with amino acids 485-502 (C-terminus).21Phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled antibodies to CD3 and CD45RA, phycocyanin-5 (PC5)–labeled CD19 and mouse IgG1 antibodies were from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, CA). Mouse IgG2a and PE-CD41 antibodies were from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG2a antibodies were from Southern Biotechnology Associates (Birmingham, AL). Pure OKT3 (anti-CD3) was kindly provided by Dr Michael Vincent, Department of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA).

Flow cytometry

Platelets were resuspended in platelet buffer at 0.5 × 109/mL, stained with FITC-CD41 antibody for 20 minutes at approximately 22°C and analyzed on the FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). A total of 20 000 CD41+ events was collected.

For intracellular staining, PBMCs at 5 × 105 cells in 100 μL were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1%Triton-X100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as described.33 34 Cells were blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and reacted with 10 μg/mL WASP 5A5 mAb or mouse IgG2a for 20 minutes on ice and washed twice with PBS, 1% fetal calf serum, 0.1% sodium azide, followed by FITC-labeled goat anti–mouse IgG2a antibodies (10 μg/mL) for 20 minutes on ice. Cells were washed and analyzed on FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) immediately. Where noted, PBMCs were stained before fixing with 4% formaldehyde with surface marker antibodies PE-CD3 and PC5-CD19 or PC5-CD3 and PE-CD45RA to distinguish T and B cells or naive and memory T cells. A total of 10 000 cells, which were gated based on forward and side scatter or CD3, CD19 and CD45RA markers, were recorded. The M1 area (positive fluorescence) was set so that 1% of normal cells stained positive with isotype control.

Activation of T cells in vitro

To obtain in vitro activated T lymphocytes, PBMCs (2 × 106/mL) were cultured in the presence of 100 ng/mL anti-CD3 mAb (OKT3), 5 μg/mL anti-CD28 mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and 100 U/mL recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2; obtained through the Biological Response Modifiers Program of the National Cancer Institute) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (complete RPMI) for 3 days and maintained in complete RPMI supplemented with 100 U/mL rIL-2 for 9 days.

Results

Case report

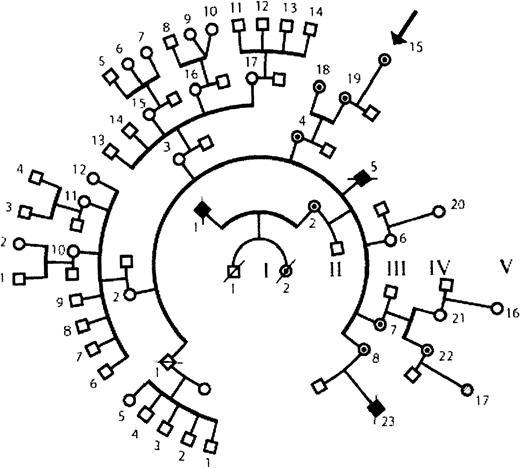

The patient was born prematurely (birth weight, 2000 g). A routine blood count in the nursery revealed that she had thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 25 000/μL). Following discharge from the nursery her growth and development were normal. On several occasions she developed petechiae on her extremities. No severe infections were noted; she had otitis media on 3 occasions during the first year of life. She had no untoward reactions to routine immunizations. She never developed eczema and never had bloody diarrhea. Now in her third year of life, she bruises easily and has many posttraumatic ecchymoses. Her platelet count varies between 50 000 and 75 000/μL. She appeared to have a mild form of WAS. Her family history includes 2 suspected and 1 well-documented35 case of WAS (Figure1).

Family tree.

The pedigree shows 5 generations. The patient under study, V-15, is indicated by an arrow. One documented case of WAS is the patient's maternal cousin (IV-23) who had an intron 6 splice site mutation, (IVS6 −1G>A). Two other relatives died in infancy of suspected WAS (II-1 and III-5). There are 6 known carrier females (III-4, III-7, III-8, IV-18, IV-19, and IV-22) in addition to the patient under study. The genotype is not defined for V-17. Symbols used are male (box), female (circle), deceased (slash), affected male (filled), female carrier (dotted fill), and unaffected subject (open symbol).

Family tree.

The pedigree shows 5 generations. The patient under study, V-15, is indicated by an arrow. One documented case of WAS is the patient's maternal cousin (IV-23) who had an intron 6 splice site mutation, (IVS6 −1G>A). Two other relatives died in infancy of suspected WAS (II-1 and III-5). There are 6 known carrier females (III-4, III-7, III-8, IV-18, IV-19, and IV-22) in addition to the patient under study. The genotype is not defined for V-17. Symbols used are male (box), female (circle), deceased (slash), affected male (filled), female carrier (dotted fill), and unaffected subject (open symbol).

Lymphocyte function studies

The mitogenic response of lymphocytes to CD3 antibodies, concanavalin A, phytohemagglutinin, and pokeweed mitogen as well as diphtheria and tetanus antigens was decreased (Table1) along with the number of CD3+ cells. Her serum immunoglobulin levels were within normal range. The titers of antibodies to tetanus andHaemophilus influenzae B were also normal. The levels of antibodies to several types of capsular pneumococcal polysaccharide antigens were slightly depressed (Table 1). If the patient had been male, the clinical and immune function findings would have suggested a diagnosis of mild WAS.

Immunologic values of the female WAS patient

| Assay . | Patient . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus for proliferation of PBMCs 3H thymidine, cpm | ||

| OKT3 | 25 500 | 121 800 |

| PHA | 85 300 | 199 200 |

| Con-A | 70 500 | 79 800 |

| Poke weed | 41 400 | 61 800 |

| Tetanus | 12 800 | 31 600 |

| Diphteria | 18 900 | 25 100 |

| Specific antibodies, ng/mL | ||

| Hib-PRP | 2 700 | > 1 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 3 | 135 | 400-11 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 14 | 6 400 | 12 400 (mean) |

| Pneumococcus type 19 | 3 400 | 1 300-110 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 23 | 4 100 | 660-250 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 26 | 400 | 860-38 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 51 | < 100 | 460-22 000 |

| Tetanus | 1.4 IU/mL | 0.15-7.0 IU/mL |

| Enumeration of PBMCs, % | ||

| CD3 (T cells) | 46 | 65-75 |

| CD4 | 26 | 35-50 |

| CD8 | 14 | 18-30 |

| CD16 (NK) | 27 | 5-15 |

| CD19 (B cell) | 24 | 19-35 |

| CD45 (leukocytes) | 95 | 95-100 |

| Serum immunoglobulin, mg/dL | ||

| IgG | 551 | 400-1 300 |

| IgA | 41 | 20-230 |

| IgM | 85 | 30-120 |

| IgG1 | 336 | 290-680 |

| IgG2 | 164 | 30-330 |

| IgG3 | 34 | 13-80 |

| IgG4 | 16 | 1-120 |

| IgE | 20 U/mL | 0-30 U/mL |

| Assay . | Patient . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus for proliferation of PBMCs 3H thymidine, cpm | ||

| OKT3 | 25 500 | 121 800 |

| PHA | 85 300 | 199 200 |

| Con-A | 70 500 | 79 800 |

| Poke weed | 41 400 | 61 800 |

| Tetanus | 12 800 | 31 600 |

| Diphteria | 18 900 | 25 100 |

| Specific antibodies, ng/mL | ||

| Hib-PRP | 2 700 | > 1 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 3 | 135 | 400-11 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 14 | 6 400 | 12 400 (mean) |

| Pneumococcus type 19 | 3 400 | 1 300-110 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 23 | 4 100 | 660-250 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 26 | 400 | 860-38 000 |

| Pneumococcus type 51 | < 100 | 460-22 000 |

| Tetanus | 1.4 IU/mL | 0.15-7.0 IU/mL |

| Enumeration of PBMCs, % | ||

| CD3 (T cells) | 46 | 65-75 |

| CD4 | 26 | 35-50 |

| CD8 | 14 | 18-30 |

| CD16 (NK) | 27 | 5-15 |

| CD19 (B cell) | 24 | 19-35 |

| CD45 (leukocytes) | 95 | 95-100 |

| Serum immunoglobulin, mg/dL | ||

| IgG | 551 | 400-1 300 |

| IgA | 41 | 20-230 |

| IgM | 85 | 30-120 |

| IgG1 | 336 | 290-680 |

| IgG2 | 164 | 30-330 |

| IgG3 | 34 | 13-80 |

| IgG4 | 16 | 1-120 |

| IgE | 20 U/mL | 0-30 U/mL |

Platelet size

Measurement of platelet size relative to standardized latex spheres showed that the effective mean diameter of the patient's platelets was 2.02 μm at age 6 months and 1.97 μm at 14 months. In contrast, the diameter of normal platelets is 2.23 ± 0.17 μm and that of nonsplenectomized WAS patients is 1.82 ± 0.10 μm.29

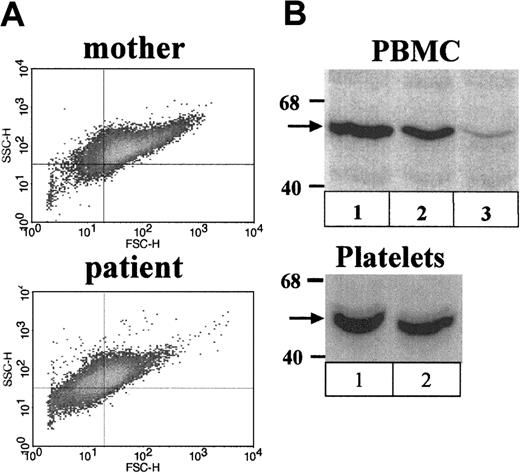

The size of the patient's platelets was examined also by flow cytometry of isolated platelets stained with CD41-PE mAb. Density plots showed that the patient's platelets were small (decreased forward scatter) relative to platelets of unaffected control individuals (not shown) and those of her mother (Figure2A).

Analysis of platelets and PBMCs.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of platelets. Shown are density plots of isolated platelets stained with FITC-CD41of the patient's mother (top panel) and the patient (bottom panel). Note the decreased mean forward scatter of the patient's platelets relative to those of her mother. (B) Western blots stained with WASP W-485 antibody. Shown are PBMCs (top panel) and platelets (bottom panel) of the (1) patient's mother, (2) the female patient, and (3) PBMCs of an unrelated typical WAS patient (exon 2; G252A).

Analysis of platelets and PBMCs.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of platelets. Shown are density plots of isolated platelets stained with FITC-CD41of the patient's mother (top panel) and the patient (bottom panel). Note the decreased mean forward scatter of the patient's platelets relative to those of her mother. (B) Western blots stained with WASP W-485 antibody. Shown are PBMCs (top panel) and platelets (bottom panel) of the (1) patient's mother, (2) the female patient, and (3) PBMCs of an unrelated typical WAS patient (exon 2; G252A).

WASP levels

The patient's PBMCs were analyzed for WASP content by Western blot. WASP levels for the female patient were lower than normal (mean of 60% of normal level, 2 cell isolates; Figure 2B, lanes 1 and 2), but higher than levels in typical WAS patients, which are generally in the range 0% to 20%.22 A typical WAS patient examined in parallel had 5% of normal levels (lane 3). Levels reported for PBMCs of the female patient's affected cousin were 10% of normal.22 WASP was also examined by Western blot in platelets of the female patient. The level measured on a single isolate was 85% of normal (Figure 2C).

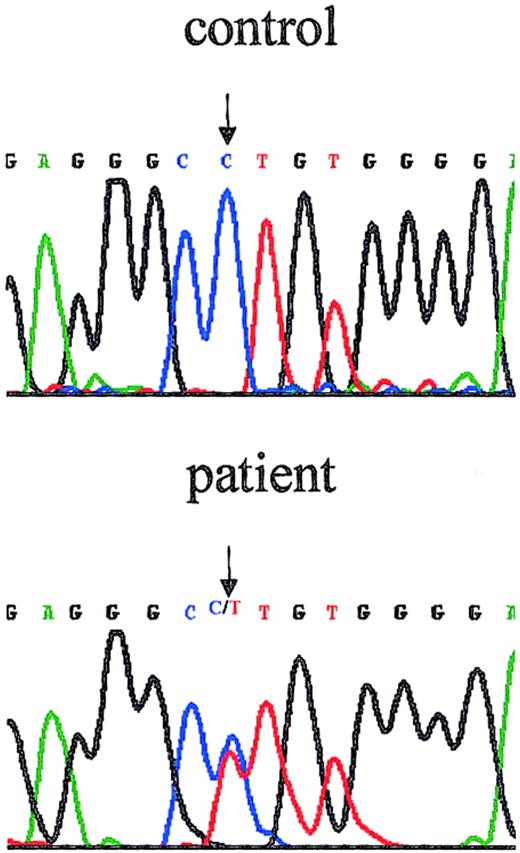

Mutation analysis

The patient's maternal cousin was known to have an acceptor site mutation in intron 6, (intervening sequence 6 [IVS6] −1G>A).35 Sequencing of this region of the patient's DNA showed 2 peaks at position −1 of intron 6 representing nucleotides G and A, demonstrating that the patient is heterozygous for the splice site mutation in intron 6 (Figure 3). The possibility of an additional WASP mutation on the patient's paternal X chromosome was rendered unlikely by sequencing all 12 exons, all intron borders, and the near promoter region. No additional mutation was found. Reverse transcription of RNA isolated from the patient's PBMCs followed by amplification and sequencing showed only normal WASP sequence, indicating the absence of detectable levels of alternative splice products.

The female patient is heterozygous for WASPmutation.

The chromatograph shows the reverse direction sequence of the region that includes the intron 6 border. The patient's sequence exhibits 2 peaks at position (−1), precisely the position of the mutation previously reported for her maternal cousin (IVS6 −1G>A).

The female patient is heterozygous for WASPmutation.

The chromatograph shows the reverse direction sequence of the region that includes the intron 6 border. The patient's sequence exhibits 2 peaks at position (−1), precisely the position of the mutation previously reported for her maternal cousin (IVS6 −1G>A).

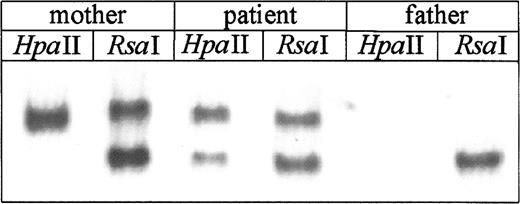

X chromosome inactivation

X chromosome inactivation studies of PBMCs showed that the patient's mother, as anticipated for WAS carriers, had only one allele amplified after HpaII digestion, consistent with preferential inactivation of her X chromosome bearing theWASP mutation (Figure 4). In contrast, PBMCs of the female patient showed 2 bands afterHpaII digestion, corresponding to active paternally and maternally derived alleles and indicating a random pattern of X inactivation in her mature blood cells (Figure 4).

Analysis of X chromosome inactivation.

DNA was isolated from PBMCs and after restriction digestion with eitherRsaI and HpaII or RsaI alone, was amplified using primers specific for the sequences flanking methylation sensitive restriction sites in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene. Amplified products were electrophoresed on nondenaturing gel and detected by silver stain. In the RsaI digest both active (unmethylated) and inactive (methylated) alleles are amplified, whereas after HpaII digest only inactive allele is amplified. Random X inactivation is identified by presence of 2 bands afterHpaII digestion; this pattern was found for the patient. In contrast, the patient's mother has only one band, indicating nonrandom inactivation. As anticipated, only one band was found inRsaI digests of the father's DNA.

Analysis of X chromosome inactivation.

DNA was isolated from PBMCs and after restriction digestion with eitherRsaI and HpaII or RsaI alone, was amplified using primers specific for the sequences flanking methylation sensitive restriction sites in exon 1 of the androgen receptor gene. Amplified products were electrophoresed on nondenaturing gel and detected by silver stain. In the RsaI digest both active (unmethylated) and inactive (methylated) alleles are amplified, whereas after HpaII digest only inactive allele is amplified. Random X inactivation is identified by presence of 2 bands afterHpaII digestion; this pattern was found for the patient. In contrast, the patient's mother has only one band, indicating nonrandom inactivation. As anticipated, only one band was found inRsaI digests of the father's DNA.

WASP expression examined by flow cytometry

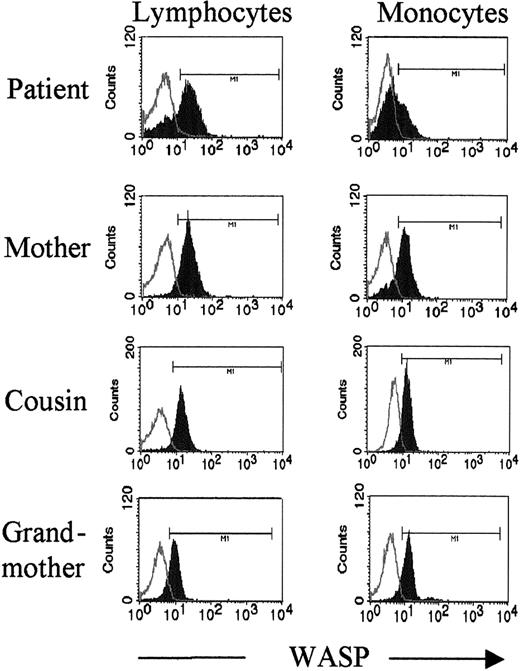

The PBMCs of the patient and her mother were examined by flow cytometry after intracellular staining with WASP mAb 5A5.34 For the patient's mother all lymphocytes and most monocytes were WASPbright (Figure5, second panel). In contrast, lymphocytes and monocytes of the patient were detected as both WASPbright and WASPdim populations (Figure 5, top panel). Moreover, the ratio of WASPbright and WASPdim differed for lymphocytes and monocytes. The patient's lymphocytes were highly skewed in favor of the WASPbright population. Only approximately 30% of lymphocytes, but 65% of monocytes, were WASPdim (Figure5). A minor population of WASPdim monocytes was noted for the mother. As a control, PBMCs examined for 2 typical WAS patients (intron 8, (+2) GAGT del and exon 10, T1055ins) showed only WASPdim lymphocytes and monocytes (data not shown).

Flow cytometry reveals 2 populations of lymphocytes and monocytes in the female patient.

PBMCs were stained intracellularly with WASP mAb 5A5. Lymphocytes and monocytes were gated on forward and side scatter. Note the presence of 2 populations, WASPbright and WASPdim, for both lymphocytes and monocytes of the patient. Lymphocytes of her mother are all WASPbright; the mother's monocytes are primarily WASPbright with a small WASPdim population. For the patient's cousin (IV-22) and grandmother (III-4), who are both carriers, all lymphocytes and monocytes were WASPbright. Open histograms indicate isotype control; closed histograms, WASP staining.

Flow cytometry reveals 2 populations of lymphocytes and monocytes in the female patient.

PBMCs were stained intracellularly with WASP mAb 5A5. Lymphocytes and monocytes were gated on forward and side scatter. Note the presence of 2 populations, WASPbright and WASPdim, for both lymphocytes and monocytes of the patient. Lymphocytes of her mother are all WASPbright; the mother's monocytes are primarily WASPbright with a small WASPdim population. For the patient's cousin (IV-22) and grandmother (III-4), who are both carriers, all lymphocytes and monocytes were WASPbright. Open histograms indicate isotype control; closed histograms, WASP staining.

The PBMCs of additional carrier females in the patient's family were also stained with mAb 5A5. The patient's cousin and grandmother showed single populations of WASPbright lymphocytes and monocytes (Figure 5, third and fourth panels). The small population of WASPdim monocytes noted for the mother was not detected for the cousin or grandmother (Figure 5) or for unaffected control females (data not shown).

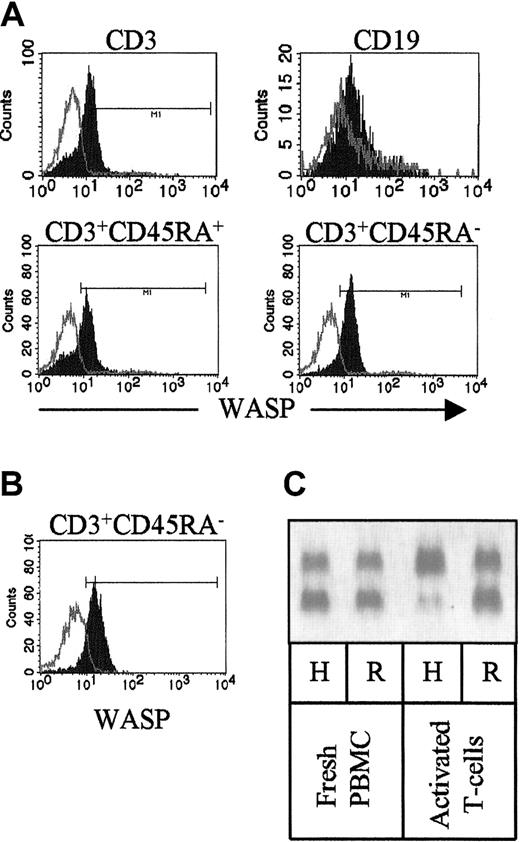

To further analyze the expression of WASP, subpopulations of the patient's lymphocytes were identified by surface staining with mAbs to CD3, CD45RA, and CD19 prior to intracellular staining with WASP mAb 5A5. Whereas the patient's naive T cells (CD3+CD45RA+) consisted of both WASPbright and WASPdim cells, her memory T cells (CD3+CD45RA−) were all WASPbright (Figure 6). The patient's B cells, identified by CD19 staining, were largely WASPdim (Figure 6).

Distribution of WASPbright and WASPdim cells of the patient examined by flow cytometry.

(A) Isolated PBMCs were surface stained with marker antibodies to CD3 and CD45RA or CD19 prior to intracellular staining with 5A5 mAb. Note that the CD3+ cells consist of both WASPbrightand WASPdim cells. All WASPdim cells are within the CD3+CD45RA+ (naive) populations, whereas CD3+CD45RA− cells are only WASPbright. B cells (CD19+) are largely WASPdim. Open histograms indicate isotype control; closed histograms, WASP staining. (B) PBMCs were activated with OKT3 mAb, anti-CD28 mAb, and rIL-2 for 3 days, expanded with rIL-2 for 9 days, and stained as in panel A. Note that only WASPbrightCD3+CD45RA− were present after activation. (C) X chromosome inactivation of freshly isolated PBMCs (left) and T cells after activation in vitro (right). Note that in vitro activated T cells have paternal (wild-type) X chromosome as active. H indicatesHpaII + RsaI digest; R, RsaI digest.

Distribution of WASPbright and WASPdim cells of the patient examined by flow cytometry.

(A) Isolated PBMCs were surface stained with marker antibodies to CD3 and CD45RA or CD19 prior to intracellular staining with 5A5 mAb. Note that the CD3+ cells consist of both WASPbrightand WASPdim cells. All WASPdim cells are within the CD3+CD45RA+ (naive) populations, whereas CD3+CD45RA− cells are only WASPbright. B cells (CD19+) are largely WASPdim. Open histograms indicate isotype control; closed histograms, WASP staining. (B) PBMCs were activated with OKT3 mAb, anti-CD28 mAb, and rIL-2 for 3 days, expanded with rIL-2 for 9 days, and stained as in panel A. Note that only WASPbrightCD3+CD45RA− were present after activation. (C) X chromosome inactivation of freshly isolated PBMCs (left) and T cells after activation in vitro (right). Note that in vitro activated T cells have paternal (wild-type) X chromosome as active. H indicatesHpaII + RsaI digest; R, RsaI digest.

In addition, activated T lymphocytes (CD3+CD45RA−) obtained by culturing PBMCs in the presence of anti-CD3 mAb, anti-CD28 mAb, and rIL-2 were all WASPbright (Figure 6B). In contrast to freshly isolated PBMCs, only paternal (wild-type) X chromosome was active in the in vitro–activated T cells, representing selection against the mutantWASP gene during activation/terminal differentiation (Figure6C).

Discussion

We describe data on a 14-month-old girl with symptoms of WAS-like disease and random X inactivation in blood cells. WASP levels in the patient's PBMCs and platelets are intermediate between normal levels and those of WAS patients. Sequencing of intron 6 revealed heterozygosity for the acceptor site mutation, (IVS6 −1G>A). This mutation was previously described in the patient's maternal cousin who had WAS.35 Flow cytometry after intracellular staining of WASP revealed 2 distinct populations of patient lymphocytes and monocytes, WASPbright and WASPdim.

The demonstration that this patient has both thrombocytopenia and small-sized platelets is significant because decreased platelet volume is prominent among the criteria used to support diagnosis of WAS.29 The patient's mother, also a WAS carrier, has normal platelet number and size. Sizing analysis showed that the patient's platelets are smaller than normal but larger than platelets from WAS patients. Although we were not able to detect 2 populations of platelets, the intermediate size and presence of 85% of normal WASP levels in platelets suggest that the female patient has WASP+ and WASP− platelet subpopulations. In contrast WASP was nondetectable in platelets of 18 typical WAS patients including the affected cousin of the female patient.22

Female carriers of WAS have nonrandom X chromosome inactivation in blood cells and are disease-free due to preferential maturation/survival of cells with the X chromosome bearing the wild-type gene.23-28 This selection process occurs at the early stages of hematopoietic development.27,28 Previous reports have described other female patients with WAS symptoms.36-40 Theoretically, expression of disease in a female heterozygous for a WASP mutation could result from abnormalities at either of 2 levels: (1) in the mechanism of transcriptional X chromosome silencing in hematopoietic stem cells or (2) in the subsequent process that leads to preferential survival and expansion of cells that bear the active wild-type X chromosome.41

In a previously reported case that was examined at the molecular level, a female heterozygous for a WASP mutation had symptoms of classical WAS and a nonrandom pattern of X inactivation.40The WASP mutation resided on her paternally derived chromosome, which was active in all blood cells. The authors hypothesized that the patient's disease was due to defect in the patient's maternal XIST gene, which is required to be expressed on the inactive X chromosome. Mutation in the XISTgene on one X chromosome can cause nonrandom X chromosome inactivation.42 In contrast, for the patient in the present study, the maternal X chromosome with the WASPmutation and paternal X chromosome with wild-type WASP are each active in a subpopulation of her blood cells (Figure 4), suggesting that the patient's disease is not due to a defect in the XIST-mediated transcriptional silencing process. Rather, the findings suggest that the defect is at the level of subsequent events that normally lead to proliferation/survival disadvantage of blood cells bearing the active mutant X chromosome.

A potential explanation for the random X inactivation pattern in the patient is the presence of a second defect on her paternal X chromosome. This possibility is considered unlikely because no secondWASP mutation was found on sequencing the entire gene. Also WASP is expressed at approximately normal levels in some of her cells. Moreover, no symptoms consistent with any other X-linked disease were noted in the female patient or her father.

In addition to the Western blots showing intermediate WASP levels in her PBMCs, analysis by flow cytometry showed that lymphocytes and monocytes of the female patient include both WASP− and WASP+ populations. These findings together with the nonrandom X chromosome inactivation in her peripheral blood cells indicate a failure of the early selection process at the level of progenitor/precursor cells.

The significance of the minor population of WASPdimmonocytes in the patient's mother, but not in other carrier females in the family, is not understood. Small populations of WASPdimmonocytes have been reported for other disease-free female carriers of WASP mutations.43 In that study, WASPdim cells constituted 20% or less of total monocytes for 7 of the carriers, and these females had only WASPbright lymphocytes, suggesting that the proliferation/survival disadvantage of cells with active X chromosomes bearing WASP mutations is less selective in monocytes than in lymphocytes. However, 2 female carriers of WASP missense mutations, which cause mild disease in patients, had substantial WASPdim monocyte subpopulations (30%, 50%) and measurable WASPdim lymphocyte subpopulations, suggesting that the stringency of selection depends also on the severity of the mutation. In contrast to the 2 latter mild mutations, the mutation in the present study causes severe disease and is expected to lead to stringent selection.

The stringency of lymphocyte selection is further reinforced by the finding that the female patient's naive circulating T cells included both WASP− and WASP+ cells, and her memory T cells (CD45RA−), the result of antigen stimulation in vivo, as well as her in vitro stimulated memory T cells were exclusively WASP+. These findings suggest that the failure of early selection at the level of progenitor/precursor cells has unmasked an additional selection process during activation/terminal T-cell differentiation. For the in vitro–activated T cells, selection against the mutant WASP allele was documented also by nonrandom inactivation.

Certain of the findings for the female patient echo those recently reported for a WAS patient with a reversion of his missense mutation in a subfraction of his T cells. In the revertant patient, naive T cells consisted of WASPdim and WASPbrightsubpopulations, whereas memory T cells were WASPbright.44 Selection against the mutant WASP allele during activation/terminal T-cell differentiation, evident in the female patient and the male revertant patient, may serve in disease-free carriers as a silent backup mechanism or checkpoint.

Although the female patient and her mother are heterozygous for the same WASP mutation, the mother is a disease-free WAS carrier, and the daughter has symptoms of the disease. The fact that patient's mature blood cells bearing a severe WASP mutation on active X chromosome survive hematopoietic selection processes appears to be responsible for the development of symptoms of WAS. The cumulative findings suggest that the patient's phenotype is due to an abnormality of postsilencing hematopoietic cell selection process at the level of stem cells and early progenitor cells rather than an abnormality of XIST-mediated transcriptional X chromosome silencing mechanism. As a result of defective selection, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets expressing the defectiveWASP gene survive and contribute to the development of the disease.

We are grateful to the family of the patient for their cooperation in providing blood samples and pedigree information and to Dr Charles Davis, who cares for the patient, for his cooperation. We thank Dr Shigeru Tsuchiya and Dr Shin Kawai (Department of Pediatric Oncology, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan) for providing 5A5 monoclonal antibody. We thank Susan Mitchell and Rosanne Stein (CBR Laboratories, Boston, MA) for X chromosome inactivation analysis. We thank Dr William Strauss (Harvard Institute of Human Genetics) for clinical data, advice, and helpful discussion and Dr Michael Vincent for providing OKT3 antibody. We are grateful to Dr Peter Nigrovic for providing immunologic values of the patient.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 14, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0388.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL59561, AI39574, and GCRC RR02172.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Eileen Remold-O'Donnell, The Center for Blood Research, 800 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:remold@cbr.med.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal