CAMPATH antibodies recognize CD52, a phosphatidylinositol-linked membrane protein expressed by mature lymphocytes and monocytes. Since some antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs) differentiate from a monocytic progenitor, we investigated the expression of CD52 on dendritic cell subsets. Four-color staining for lineage markers (CD3, 14, 16, 19, 20, 34, and 56), HLA-DR, CD52, and CD123 or CD11c demonstrated that myeloid peripheral blood (PB) DCs, defined as lineage−HLA-DR+CD11c+, express CD52, while expression by CD123+ lymphoid DCs was variable. Depletion of CD52+ cells from normal PB strongly inhibited their stimulatory activity in an allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction and also reduced the primary autologous response to the potent neoantigen keyhole limpet hemocyanin. CD52 is thus expressed by a myeloid subset of PBDCs that is strongly allostimulatory and capable of initiating a primary immune response to soluble antigen. Administration of alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against CD52, to patients with lymphoproliferative disorders or as conditioning for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation resulted in a marked reduction in circulating lineage−HLA-DR+ DCs (mean 31-fold reduction,P = .043). Analysis of monocyte-derived DCs in vitro revealed a reduction in CD52 expression during culture in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-4, with complete loss following activation-induced maturation with lipopolysaccharide. In contrast to the findings in PB, epidermal and small-intestine DCs did not express CD52, suggesting either that transit from blood to epidermis and gut is associated with loss of CD52 or that DCs in these tissues originate from another population of cells.

Introduction

The CAMPATH series of monoclonal antibodies recognize CD52, a phosphatidylinositol-linked antigen that is expressed by most mature lymphocytes and monocytes.1 CAMPATH-1M and 1G are rat IgM and IgG antibodies that have been used in vitro and in previous phase 1/2 clinical trials. A humanized form of the antibody, CAMPATH-1H (approved name Alemtuzumab), has recently been approved for refractory B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Several properties of the CD52 antigen make it a particularly good therapeutic target. These include the high antigen density, lack of internalization, and the proximity of the antibody binding site to the cell surface, which may contribute to the efficiency of complement-mediated cytotoxicity that characterizes CAMPATH antibodies.2 Administration of CAMPATH antibodies results in the rapid clearance of normal and malignant T and B lymphocytes from the circulation, a finding that has led to its use as an immune suppressant3 and in the treatment of mature T and B lymphoproliferative disorders.4 5

CAMPATH antibodies have also proved to be a convenient and efficient means of achieving T-cell depletion in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).6,7Conditioning regimens that incorporate CAMPATH antibodies have been associated with a low incidence of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and rejection.8-11 Although these effects can be explained by depletion of donor and recipient T cells, we investigated the effects of CAMPATH antibodies on antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs), which have recently been shown to have a role in the initiation of GvHD12 and, by virtue of their monocytic lineage,13 might also express CD52.

Materials and methods

CD52 expression by blood and tissue DCs

Phenotypic studies.

Measurements of peripheral blood (PB) DC numbers were performed on EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood from healthy volunteers and patients receiving alemtuzumab (Millenium-Ilex, Guildford, United Kingdom) as therapy for lymphoproliferative disorders or as conditioning treatment for reduced-intensity allo-HSCT. Patients with lymphoproliferative disorders received 30 mg of intravenous alemtuzumab on alternate days and allo-HSCT patients received 20 mg daily for 5 consecutive days. The studies were approved by the local research and ethics committee and patients gave informed consent. No concurrent cytotoxic drugs were administered to the patients under study. Steady-state numbers of PBDCs were measured in 12 healthy volunteers and in 5 patients prior to and on day 5 of treatment with alemtuzumab.

Circulating DC numbers were measured in red cell–lysed whole blood (Optilise-C; Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom) by 3-color flow cytometry, using a cocktail of phycoerythrin (PE)–labeled lineage (lin) markers including CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, 20, CD34, and CD56 (BD Biosciences, Cowley, United Kingdom), a PE-Cy5–labeled HLA-DR; and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) CD45 (Beckman Coulter). Appropriate isotype-matched controls and single-labeled samples were performed to set color compensation. At least 100 HLA-DR+lin−CD45+ events were acquired on an EPICS IV flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) equipped with a 488-nm Argon laser, and the absolute number of circulating DCs was calculated from the total white blood cell count measured on a Sysmex SE9000 hematology analyzer. The significance of changes in peripheral blood cell numbers was assessed by the Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

Measurement of CD52 expression on DC subsets was performed by 4-color flow cytometry on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors. DCs were identified using the above lineage markers labeled with FITC and HLA-DR labeled with PE-Cy5. Myeloid and lymphoid subsets were differentiated with PE-labeled CD11c or CD123 and CD52-expressing cells were differentiated with biotinylated CAMPATH-1G (Therapeutic Antibody Centre, Oxford, United Kingdom) and a streptavidin PE–Texas red conjugate (ImmunoTech, Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). At least 300 000 events were acquired and color compensation was performed off-line with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Stanford, CA), using single-labeled samples and appropriate isotype-matched controls. Except where indicated, monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences.

To determine whether tissue DCs express CD52, we stained adjacent sections of normal skin and small intestine with S-10014(Dako, Ely, United Kingdom), an antibody that detects cutaneous DCs (Langerhans cells) as well as DCs in other tissues, and CD52 (Therapeutic Antibody Centre). Expression was visualized with a biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, United Kingdom) and a streptavidin biotin complex detection system (Dako).

Functional studies.

Cell purification. For the functional assays of antigen presentation, peripheral blood from healthy volunteers was taken into 10 U/mL preservative-free heparin and mononuclear cells (PBMCs), prepared by Ficol Hypaque centrifugation at 400g for 20 minutes at room temperature, followed by 2 washes with phosphate-buffered saline. Further cell purification was performed with immunomagnetic beads used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purification of responder T cells for the allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reactions (allo-MLRs) was performed by negative depletion of CD14, HLA-DR/DP, and CD16 and CD56+cells from PBMCs (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). For the autologous presentation assays, CD4+ T cells were isolated with the above cocktail with the addition of anti-CD8. CD52 depletion was performed with CAMPATH-1G (Therapeutic Antibody Centre) and sheep antirat conjugated beads (Dynal). Cell purity was confirmed by flow cytometry and ranged from 85% to 97%. In some experiments, further depletion of CD123+ cells from the CD52− fraction was performed with immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Lineage depletion was achieved with the lineage cocktail of antibodies described above and goat antimouse conjugated immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi). For the add-back studies, T cells were prepared by the negative isolation technique described above. CD14+ and CD19+ cells were prepared by positive selection with immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi).

Allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction.

Purified T lymphocytes were cocultured for 5 days at 105per well in RPMI/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C and 5% CO2, in triplicate, with irradiated (35 Gy) allogeneic stimulator cells comprising either unfractionated PBMCs or the same number of antibody-depleted PBMCs at the stated concentrations. In some experiments, purified monocytes, T cells, and B cells were added back to CD52-depleted cells in the same proportion in which they had been present prior to depletion. This was achieved by selecting from the same volume of PBMCs used to arrive at the stated number of CD52-depleted cells. On day 5, 3H-thymidine (0.0185 Bq [0.5 μCi] per well; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) was added for the final 20 hours. The cells were then harvested and 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation. The significance of differences in response to PBMCs and CD52-depleted cells was assessed by Student ttest.

Primary antigen–specific responses.

To assess presentation of primary antigen by CD52-expressing cells, we used irradiated normal PBMCs or the same number of antibody-depleted cells as stimulators and purified autologous CD4 cells as responders in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum. Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom) was added where indicated at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. Add-back of CD3-, CD14-, and CD19-expressing cells was achieved as outlined above.3H-thymidine was added on day 7 for the final 20 hours and the cells were harvested and analyzed as previously described.

CD52 expression by monocyte-derived DCs

Monocytes were enriched from PBMCs by plastic adherence in RPMI + 1% FCS for 2 hours at 37°C. After removal of nonadherent cells, the adherent cells were washed and then incubated in RPMI + 10% FCS with 100 ng/mL GM-CSF (Novartis, Camberley, United Kingdom) and 500 U/mL interleukin-4 (IL-4) (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) for 6 days. Maturation was achieved by the addition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma), 100 ng/mL, to an aliquot of the cells on day 4. Differentiation to DCs was assessed by staining with CD1a, CD14, CD80, and CD83 (BD Biosciences) and CD52 (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) and analysis by flow cytometry. The significance of changes in the percentage of cells expressing CD52 was assessed by pairedt test.

Results

Peripheral blood dendritic cells express CD52

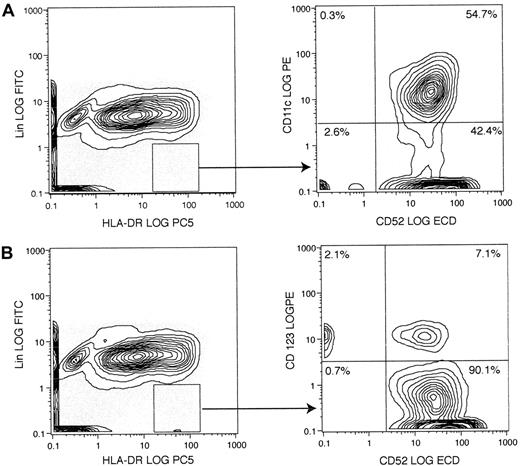

Cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage share a common progenitor with some types of DC and are known to express CD52. We therefore investigated whether peripheral blood DCs, defined by the lack of lineage markers and strong expression of HLA-DR, also express CD52. Analysis by 4-color flow cytometry revealed that CD11c+“myeloid” DCs uniformly express CD52 (Figure1A), while CD52+ and CD52− populations of CD123+ lymphoid DCs were evident (Figure 1B). A population of lin−HLA-DR+CD52+ cells negative for both CD11c and CD123 was also suggested by these experiments, and this was confirmed by the addition of CD123 and CD11c to the lineage cocktail and staining for CD52 and HLA-DR (data not shown).

Analysis of normal peripheral blood DCs for the expression of CD52 and either CD11c or CD123.

PBMCs from a healthy donor were stained for lineage markers (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD34, and CD56), HLA-DR, CD52, and either CD11c (A) or CD123 (B). The majority of CD11c-expressing lin−HLA-DR+ DCs also express CD52, whereas CD123+ DCs varied in their expression of CD52. The result shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. ECD indicates energy-coupled dye (ECD-Streptavidin; Immunotech, Beckman Coulter).

Analysis of normal peripheral blood DCs for the expression of CD52 and either CD11c or CD123.

PBMCs from a healthy donor were stained for lineage markers (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD34, and CD56), HLA-DR, CD52, and either CD11c (A) or CD123 (B). The majority of CD11c-expressing lin−HLA-DR+ DCs also express CD52, whereas CD123+ DCs varied in their expression of CD52. The result shown is representative of 3 independent experiments. ECD indicates energy-coupled dye (ECD-Streptavidin; Immunotech, Beckman Coulter).

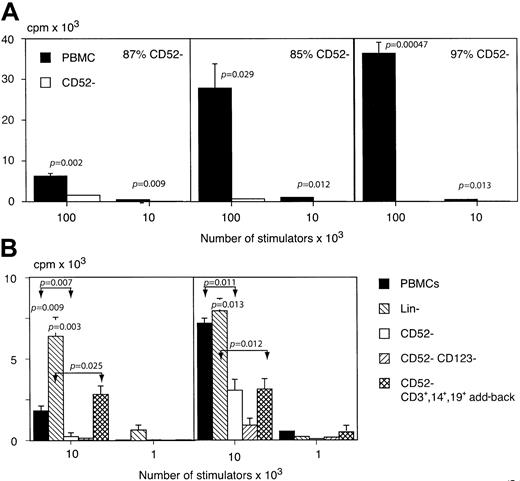

To determine whether the CD52+ DCs identified by phenotypic criteria have the appropriate functional properties, we assessed the effect of removing CD52+ cells from the stimulatory arm of the allo-MLR. CD52− cells accounted for 3.5% ± 0.8% (SEM) of PBMCs, and the efficiency of CD52 depletion varied from 85% to 97%. Cytospin and Romanowsky staining of a CD52-depleted preparation showed lymphocytes, myeloid cells, and monocytic cells, as well as platelets and a population of cells with megakaryocytic features. Phenotypic analysis revealed a variety of cell types within the CD52− fraction, including CD3 (19%), CD14 (10%), CD16 (7%), CD15 (4.5%), CD19 (2%), CD34 (16.5%), CD56 (7%), CD57 (2%), CD61 (33%), and glycophorin A (2%). In each of 3 experiments, performed with different healthy donors and responders, CD52 depletion significantly reduced allostimulatory activity (Figure2A). Since the loss of allostimulatory activity could be due to the removal of cells other than DCs, we performed further experiments in which lineage- and CD52-depleted cells with CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells added back were compared with PBMCs and CD52-depleted PBMCs (Figure 2B). These experiments showed that lineage depletion augments rather than inhibits the allo-MLR, compatible with enrichment of highly allostimulatory DCs. Add-back of purified monocytes, T cells, and B cells to CD52-depleted PBMCs variably reconstituted the allo-MLR; however, the activity was still significantly less than for the lineage-depleted cells. Depletion of the CD52− fraction with CD123 beads maintained or reduced the allo-MLR, suggesting that the loss of allostimulatory effect following CD52 depletion was not due to relative enrichment of potentially inhibitory CD123+lymphoid DCs.

The role of CD52+ cells in the allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction.

(A) The effect of depletion of CD52-expressing cells from the stimulatory arm of the allo-MLR. The proliferation of purified allogeneic T lymphocytes in response to unfractionated or CD52-depleted, irradiated allogeneic PBMCs is shown for 3 separate stimulator/responder pairs and expressed as the mean of triplicate readings + SEM. (B) The effect of lineage depletion, CD52 depletion, CD52 and CD123 depletion, or add-back of purified CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells to the CD52-depleted fraction on the allo-MLR. Lineage depletion maintained or enhanced the allo-MLR. Add-back of monocytes and lymphocytes variably reconstituted the allogeneic response to CD52-depleted cells, although not to the level observed in the lineage− cells. The CD52−CD123−fraction elicited a response similar to or further reduced compared to that of CD52− cells. The significance of the results obtained is shown above the columns in question and the values for nonadjacent columns are indicated by double arrows.

The role of CD52+ cells in the allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reaction.

(A) The effect of depletion of CD52-expressing cells from the stimulatory arm of the allo-MLR. The proliferation of purified allogeneic T lymphocytes in response to unfractionated or CD52-depleted, irradiated allogeneic PBMCs is shown for 3 separate stimulator/responder pairs and expressed as the mean of triplicate readings + SEM. (B) The effect of lineage depletion, CD52 depletion, CD52 and CD123 depletion, or add-back of purified CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells to the CD52-depleted fraction on the allo-MLR. Lineage depletion maintained or enhanced the allo-MLR. Add-back of monocytes and lymphocytes variably reconstituted the allogeneic response to CD52-depleted cells, although not to the level observed in the lineage− cells. The CD52−CD123−fraction elicited a response similar to or further reduced compared to that of CD52− cells. The significance of the results obtained is shown above the columns in question and the values for nonadjacent columns are indicated by double arrows.

To confirm the antigen-presenting capabilities of CD52-expressing cells, we studied the effect of CD52 depletion on the presentation of the potent soluble neoantigen KLH to purified autologous CD4 T lymphocytes. In each of 3 experiments with different donors, CD52 depletion significantly inhibited the primary immune response to KLH (Figure 3A). Add-back of purified CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells failed to reconstitute antigen-presenting ability, and lineage-depleted PBMCs showed enhanced activity compared with CD52-depleted cells, suggesting that CD52-expressing DCs and not cells of another type were responsible for the presentation of KLH (Figure3B). Depletion of the CD52− fraction with CD123 also failed to reconstitute the response to KLH, suggesting that the observed effect of CD52 depletion on antigen presentation is not due to the relative enrichment of CD52−CD123+lymphoid DCs.

The role of CD52+ cells in the primary immune response to KLH.

(A) The effect of CD52 depletion on the presentation of KLH by irradiated PBMCs to purified autologous CD4 T cells. Proliferation was assessed after 7 days' culture by uptake of 3H. Results shown are the mean of triplicate readings + SEM. CD52 depletion resulted in significant inhibition of the response to KLH. (B) The effect of lineage depletion, CD52 depletion, CD52 and CD123 depletion, and add-back of purified CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells to CD52-depleted cells on the presentation of KLH to autologous purified CD4 cells. Lineage depletion enhanced the presentation of KLH, while add-back of CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+cells failed to reconstitute the activity in CD52-depleted cells. Further depletion of CD123+ from the CD52− fraction had no effect. The significance of the results obtained is shown above the columns in question and the values for nonadjacent columns are indicated by double arrows. Each panel represents a separate experiment using a different donor.

The role of CD52+ cells in the primary immune response to KLH.

(A) The effect of CD52 depletion on the presentation of KLH by irradiated PBMCs to purified autologous CD4 T cells. Proliferation was assessed after 7 days' culture by uptake of 3H. Results shown are the mean of triplicate readings + SEM. CD52 depletion resulted in significant inhibition of the response to KLH. (B) The effect of lineage depletion, CD52 depletion, CD52 and CD123 depletion, and add-back of purified CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+ cells to CD52-depleted cells on the presentation of KLH to autologous purified CD4 cells. Lineage depletion enhanced the presentation of KLH, while add-back of CD3+, CD14+, and CD19+cells failed to reconstitute the activity in CD52-depleted cells. Further depletion of CD123+ from the CD52− fraction had no effect. The significance of the results obtained is shown above the columns in question and the values for nonadjacent columns are indicated by double arrows. Each panel represents a separate experiment using a different donor.

Peripheral blood dendritic cells are depleted during treatment with alemtuzumab

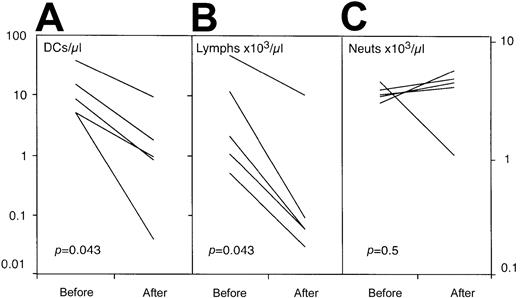

We next studied the effect of treatment with alemtuzumab on the number of circulating lin−HLA-DR+ DCs in a group of 5 patients being treated with alemtuzumab and no other agents. Previous studies had shown the normal range for PBDCs to be 21± 2.6 (SEM)/μL (n = 12) . DC numbers in the patients studied were within this range prior to therapy. The administration of alemtuzumab resulted in a significant (P = .043) reduction in circulating DCs in all patients (Figure4). As expected, a fall in the circulating number of lymphoid cells, but not neutrophils, was also noted. This is in keeping with the tissue distribution of CD52, which is expressed by mature T and B lymphocytes but not neutrophils.

The effect of alemtuzumab therapy on the number of circulating DCs, lymphocytes, and neutrophils.

The patients had received no therapy other than alemtuzumab and were studied prior to and on day 5 of intravenous treatment at a dose of 20 mg per day (allo-HSCT patients) or 30 mg on alternate days (lymphoproliferative patients). There was a significant reduction in circulating DCs (A) that paralleled the fall in lymphocyte count (B). No change in the number of circulating neutrophils was observed (C).

The effect of alemtuzumab therapy on the number of circulating DCs, lymphocytes, and neutrophils.

The patients had received no therapy other than alemtuzumab and were studied prior to and on day 5 of intravenous treatment at a dose of 20 mg per day (allo-HSCT patients) or 30 mg on alternate days (lymphoproliferative patients). There was a significant reduction in circulating DCs (A) that paralleled the fall in lymphocyte count (B). No change in the number of circulating neutrophils was observed (C).

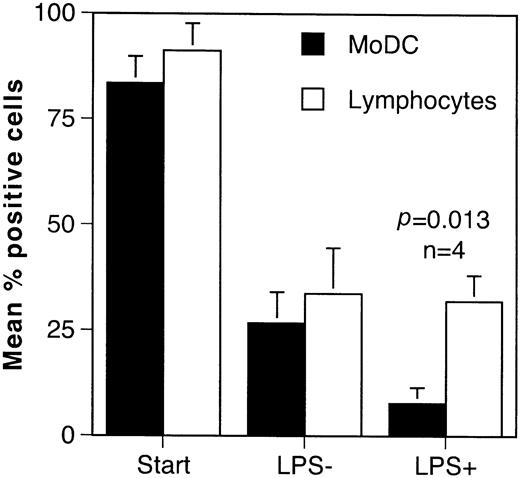

Expression of CD52 by monocyte-derived DCs and by tissue DCs in vivo

Since the effect of alemtuzumab therapy on immune responses in vivo will depend on whether CD52 is expressed by immature DCs in the tissues and mature antigen-primed DCs, we studied CD52 expression by monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) in vitro and by DCs in the normal epidermis and intestinal mucosa in vivo. DCs derived by differentiation of monocytes in GM-CSF and IL-4 showed the expected gain in CD1a and loss of CD14 expression. The addition of LPS resulted in down-regulation of CD1a and up-regulation of CD83, compatible with activation-induced maturation (data not shown). During the culture period there was a progressive fall in the proportion of cells expressing CD52 when gating was performed on the DC population. A similar loss of CD52 expression was also observed in the lymphocytic fraction, suggesting that it may be a phenomenon associated with the duration of time in tissue culture. The addition of LPS resulted in significant further loss of CD52 by MoDCs (P = .013, n = 4) but had no effect on CD52 expression by lymphocytes (Figure 5).

Changes in CD52 expression during the differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs in GM-CSF and IL-4.

The results are shown as the mean percentage of positive cells from 4 experiments performed with different healthy donors. DCs and lymphocytes were identified by their forward- and side-scatter properties and the results were analyzed by paired t test. A reduction in the number of CD52+ DCs and lymphocytes was observed during the culture period. Addition of LPS caused maturation of DCs as evidenced by up-regulation of CD83 and loss of CD1a (data not shown). This was associated with complete loss of CD52 by DCs but no further change in expression by lymphocytes.

Changes in CD52 expression during the differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs in GM-CSF and IL-4.

The results are shown as the mean percentage of positive cells from 4 experiments performed with different healthy donors. DCs and lymphocytes were identified by their forward- and side-scatter properties and the results were analyzed by paired t test. A reduction in the number of CD52+ DCs and lymphocytes was observed during the culture period. Addition of LPS caused maturation of DCs as evidenced by up-regulation of CD83 and loss of CD1a (data not shown). This was associated with complete loss of CD52 by DCs but no further change in expression by lymphocytes.

Staining of adjacent tissue sections with S100 and CD52 showed that epidermal Langerhans cells and small-intestine DCs do not express CD52 (Figure 6). The presence of melanocytes at the epidermal/dermal junction and neuronal fibrils in the submucosa of the intestine served as positive internal controls for the S100 antibody. CD52 staining was validated by the presence of lymphocytes in both tissues.

Expression of CD52 by tissue dendritic cells.

Staining of adjacent sections of normal skin and small bowel (SB) with S100 and CD52 show that DCs in these tissues do not express CD52. Langerhans cells stain positively for S100 but are uniformly negative for CD52. A normal lymphoid cell in the CD52-stained skin section is shown (*). A DC in a sample of small intestinal mucosa is similarly stained with S100 but not CD52 (indicated by the arrow). Original magnification, × 400.

Expression of CD52 by tissue dendritic cells.

Staining of adjacent sections of normal skin and small bowel (SB) with S100 and CD52 show that DCs in these tissues do not express CD52. Langerhans cells stain positively for S100 but are uniformly negative for CD52. A normal lymphoid cell in the CD52-stained skin section is shown (*). A DC in a sample of small intestinal mucosa is similarly stained with S100 but not CD52 (indicated by the arrow). Original magnification, × 400.

Discussion

Normal peripheral blood contains at least 2 DC subsets that together make up between 0.01% and 0.1% of circulating white blood cells.15,16 These include myeloid DCs defined by the absence of lineage markers and strong expression of HLA-DR, CD11c, and CD33, and a lymphoid subset that expresses the IL-3 receptor CD123 instead of CD11c or CD33. Both are strong stimulators of the allo-MLR, but only the myeloid subset, thought to be the precursor of the cutaneous Langerhans cell,17 can process soluble antigens.16 The results presented here indicate that most CD11c+ myeloid PBDCs and some CD123+ lymphoid DCs express CD52, the antigen recognized by CAMPATH antibodies. This was confirmed by functional experiments showing that the removal of CD52-expressing cells reduced both the allostimulatory activity of PBMCs and the ability to present the potent soluble neoantigen KLH to autologous T cells.

That DCs, rather than another CD52-expressing cell, were responsible for the activity in these assays was confirmed by lineage-depletion studies and by add-back of purified monocytes and lymphocytes. Lineage depletion, a maneuver known to enrich DCs, augmented both the allo-MLR and the KLH-presenting activity, while add-back of monocytes and lymphocytes variably reconstituted the allo-MLR but had no effect on the primary antigen presentation assay. Further depletion of CD123+ cells, which would additionally remove CD52− lymphoid DCs, failed to reconstitute either the allo-MLR or the ability to present KLH, suggesting that the effects observed were not due to relative enrichment of this potentially inhibitory cell type. The fact that lineage-depleted cells had a far higher activity in both assays than the CD52-depleted fraction argues against an artifact of extensive cell depletion such as enrichment of platelets and red cells, which could conceivably compromise the assays by interfering with cell-to-cell contact.

As anticipated from the observation that most PBDCs express CD52, the administration of intravenous alemtuzumab had marked effects on the numbers of peripheral blood lineage−HLA-DR+DCs. Significant depletion of DCs was observed that paralleled the expected fall in lymphocyte numbers. The level of neutrophils, which do not express CD52, was unchanged. Since alemtuzumab is an efficient complement-fixing antibody, it seems likely that the reduction in circulating DC numbers is due to elimination rather than redistribution to other sites, such as the lungs. Definitive proof of this, however, would require sequential analysis of tissue DC numbers, which is problematic in human subjects.

Our data also suggest that the expression of CD52 is a feature of an immature stage of DC development, since in vitro differentiation from monocytes in GM-CSF and IL-4 followed by activation-induced maturation in LPS was associated with progressive loss of the antigen. In addition, as recently noted by others,18 DCs in the epidermis (Langerhans cells) do not express CD52, and we now show that this is also true of DCs in the small-intestine mucosa. These findings raise questions about the role of circulating DCs, which have previously been proposed as the precursors of tissue DCs such as Langerhans cells.17 Either migration from blood to tissues is associated with loss of CD52, or DCs in these tissues must arise from another cell type. If the former is true, then, depending on the rate of turnover of DCs in that particular site, therapy with alemtuzumab should eventually reduce tissue DCs by depleting their circulating precursors. In the latter case, therapy with alemtuzumab would not affect DC numbers in tissues such as the skin and gut. Sequential studies of blood and tissue DC numbers in patients receiving long-term alemtuzumab therapy will be required to clarify this point.

These findings have important implications for the clinical use of alemtuzumab. Since their introduction during the 1980s, CAMPATH antibodies have been used as an immunosuppressive agent in patients with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis3and multiple sclerosis19 and in solid organ20as well as bone marrow transplantation.8-11 It is particularly useful in the treatment of T- and B-cell malignancies,5 21 for which a product license was recently granted. In the context of malignant disease, in which there is frequently pre-existing immunosuppression due to disease and other therapy, a relatively high incidence of opportunistic infection has been noted. While this is undoubtedly due in large measure to the depletion of T and B lymphocytes, any effect on antigen-presenting function could significantly compound this effect. Since CD52 is expressed by blood but not tissue DCs and is lost following activation-induced maturation, it seems likely that at least in the short term, antigen-presenting function will remain intact during alemtuzumab therapy. In particular, antigen-primed DCs that have matured and migrated to lymphoid tissue should be spared. The effect of depletion of PBDCs by alemtuzumab is less certain, since their role in immune function has not been defined. If this population of DCs represents the precursors of tissue DCs, then as noted above, depending on the turnover rate, alemtuzumab therapy should eventually result in impaired antigen-presenting function. Tissue depletion might be accelerated by damaging treatment modalities such as high-dose chemotherapy or radiation, since cellular injury and inflammatory stimuli are known to cause migration of DCs from the periphery into lymphoid tissue. If, on the other hand, the function of PBDCs is to process and present circulating pathogens, then alemtuzumab therapy will have rapid deleterious effects on this aspect of immune function.

CAMPATH antibodies have proved to be particularly effective when incorporated into conditioning regimens for allo-HSCT, and the findings reported here are of particular relevance in this context. Several strategies have been employed, including in vivo administration prior to and after infusion of the donor stem cells or in vitro as a means of reducing the infused T- and B-cell dose. Although never formally evaluated in randomized trials, regimens that incorporate CAMPATH antibodies have been notable for their low incidence of graft failure and GvHD.9 The risk of posttransplantation lymphoma has also been low, presumably because of depletion of donor B cells.22 Interestingly, the risk of GvHD remains low when alemtuzumab administration is confined to the pretransplant period.10,11 23 This finding has been ascribed to in vivo depletion of donor T cells by antibody carried over from the pretransplantation period. When used “in the bag” as an in vitro T-cell depletion strategy, alemtuzumab should also deplete myeloid DCs, which may reduce the risk of rejection by removing the ability to present donor histocompatibility antigens to naive host T cells that have survived conditioning therapy.

As discussed above, the effects of alemtuzumab therapy on DC populations and antigen presentation in vivo are unclear because of the lack of CD52 expression by tissue DCs and the uncertain relationship between these cells and DCs in the blood. Any effect of alemtuzumab on tissue DCs is, as noted earlier, likely to be influenced by other factors, such as tissue damage due to concurrent chemo- or radiotherapy or infection. In the context of allo-HSCT, it will be important to fully define the effects of alemtuzumab on DC function in vivo, as there is a persuasive theoretical and experimental basis for the role of these cells in the induction of GvHD. Although T lymphocytes can recognize major histocompatibility complex (MHC) disparity without the need for specialized antigen presentation,24this does not apply to unprimed MHC identical sibling transplants, where GvHD and rejection presumably require the processing and presentation of minor histocompatibility antigens by professional antigen-presenting cells. This is borne out by murine allo-HSCT experiments in which the presence of functional host DCs was required for the induction of GvHD.12 It may be possible, therefore, to design improved conditioning regimens exploiting the effects of alemtuzumab on antigen presentation.

In summary, we have shown that peripheral blood cells with the phenotype and function of myeloid dendritic cells express CD52 and are depleted by therapy with alemtuzumab. This is unlikely to have effects on antigen-presenting function in the short term, however, as tissue DCs and mature MoDCs do not express CD52 and are therefore unlikely to be depleted. Prolonged administration of alemtuzumab or concurrent tissue damage may reduce the number of DCs in the tissues by depleting their putative peripheral blood precursors; however, confirmation of this will require serial studies of tissue DC numbers.

We thank Professors Geoffrey Hale and Herman Waldmann of the University of Oxford for helpful advice and the supply of reagents for this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Stephen Devereux, Department of Haematological Medicine, Kings College Hospital, London SE5 9RS, England; e-mail: stephen.devereux@kcl.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal