A new way to identify tumor-specific genes is to compare gene expression profiles between malignant cells and their autologous normal counterparts. In patients with multiple myeloma, a major plasma cell disorder, normal plasma cells are not easily attainable in vivo. We report here that in vitro differentiation of peripheral blood B lymphocytes, purified from healthy donors and from patients with multiple myeloma, makes it possible to obtain a homogeneous population of normal plasmablastic cells. These cells were identified by their morphology, phenotype, production of polyclonal immunoglobulins, and expression of major transcription factors involved in B-cell differentiation. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis shows that these polyclonal plasmablastic cells have a gene expression pattern close to that of normal bone marrow–derived plasma cells. Detailed analysis of genes statistically differentially expressed between normal and tumor plasma cells allows the identification of myeloma-specific genes, including oncogenes and genes coding for tumor antigens. These data should help to disclose the molecular mechanisms of myeloma pathogenesis and to define new therapeutic targets in this still fatal malignancy. In addition, the comparison of gene expression between plasmablastic cells and B cells provides a new and powerful tool to identify genes specifically involved in normal plasma cell differentiation.

Introduction

To improve the knowledge and treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), a malignant plasma cell disorder,1,2 it would be useful to obtain normal cells with a phenotype as close as possible to that of malignant cells. These cells would allow the identification of genes that are dysregulated in tumor plasma cells and that may be involved in the emergence of the disease or may code for tumor antigens useful for immunotherapy strategies. In addition to the identification of myeloma-specific genes, obtaining plasma cells in vitro can be a helpful tool for studying the critical factors involved in the terminal step of B-cell differentiation. However, plasma cells are rare cells in vivo, representing only 1% to 2% of tonsillar mononuclear cells3 and less than 0.5% of bone marrow cells in healthy persons. Such polyclonal plasma cells cannot be routinely purified from healthy donors or MM patients. Therefore, the only way to get a normal counterpart of malignant plasma cells from MM patients would be to induce in vitro peripheral blood (PB) B-cell differentiation into plasma cells.

Several studies have shown that tonsillar B cells can be induced to differentiate into plasma cells in vitro.4-7 Tonsillar B cells are first activated and amplified by CD40 ligation for several days in the presence of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, or IL-10, and B-cell differentiation is then induced by removing the CD40 signal and adding IL-10 and IL-6. Concerning PB B cells, only a few studies have reported the possibility of obtaining polyclonal plasma cells from memory B cells with CD27 or CD40 triggering.8 9 The resultant cell population was heterogeneous and contained approximately 50% plasma cells defined only by lack of CD20 expression, high CD38 expression, and ability to produce polyclonal immunoglobulin.

In the current study, we demonstrate that large amounts of highly pure polyclonal plasmablastic cells (PPCs) can be reproducibly generated from the PB B cells of healthy donors and MM patients. Gene expression analysis of these PPCs using Affymetrix oligonucleotide arrays shows that they belong to a “plasma-cell” cluster including normal and malignant plasma cells that can be separated from a “B-cell” cluster including normal B cells and B-cell lines. Statistical analysis allows the identification of genes that were differentially expressed between normal plasma cells and B cells and between malignant and normal plasma cells. We describe here an original model making it possible to obtain a normal counterpart of malignant MM plasma cells that should be useful to further understand the biology of MM and to improve therapeutic developments.

Materials and methods

Cell samples

XG-1, XG-5, XG-6, and XG-16 myeloma cell lines and the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–transformed B-cell lines (EBV-1, EBV-5, EBV-14, and EBV-16) were obtained and characterized in our laboratory.10,11 Malignant plasma cells were purified from 8 patients with MM (5 at the medullar stage and 3 with plasma cell leukemia) after informed consent. Normal bone marrow plasma cells were purified in the laboratory of J.S. as described.12Polyclonal plasma cells were also obtained from a patient with reactive plasmacytosis (RP) following infection and allergy. Plasma cells from RP were proliferative in vivo, with 28% of CD138+ plasma cells in the S-phase of cell cycle. Purification of plasma cells (more than 95% plasma cells) was performed with the MI15 anti-CD138 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and anti-mouse IgG1 MACS Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Paris, France).13 PB B lymphocytes were purified from healthy volunteers using anti-CD19 MACS Microbeads (Miltenyi). For MM patients, B lymphocytes expressing κ or λ light chain were first removed using anti-κ or anti-λ mAb (Coulter-Immunotech, Marseilles, France) and anti-mouse immunoglobulin beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). CD138+ plasma cells were also depleted using the MI15 mAb. CD19+ B cells were then positively selected using anti-CD19 MACS Microbeads (Miltenyi). For the isolation of naive and memory B-cell subsets, monocytes and T cells were first removed using anti-CD14 and anti-CD3 beads (Dynal), and resultant cells were double stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD19 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD27 (Coulter-Immunotech). CD19+CD27+ and CD19+CD27− B cells were then sorted with a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

B-cell differentiation and characterization

All cultures were performed in RPMI 1640 and 10% fetal calf serum. Purified B cells were plated at 1.5 × 105/mL in the presence of 3.75 × 104/mL mitomycin-treated CD40L transfectant (a generous gift from S. Saeland, Shering-Plough, France) with various combinations of IL-2 (20 U/mL), IL-4 (50 ng/mL), IL-10 (50 ng/mL), and IL-12 (2 ng/mL) (R&D Systems, Abington, United Kingdom). After 4 days of culture, B cells were harvested and seeded at 3 × 105/mL without CD40L transfectant and with IL-2 (20 U/mL), IL-10 (50 ng/mL), IL-12 (2 ng/mL), and IL-6 (5 ng/mL). On day 6 of culture, cells were double stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD20 (Coulter-Immunotech) and PE-conjugated anti-CD38 (Becton Dickinson), and CD20−/CD38++ cells were sorted as described above. For 3-color analysis, we used FITC-conjugated anti-CD38, Cy chrome–conjugated anti-CD20, and PE-conjugated anti-CD27, anti-CD21, anti-CD22, anti-CD23, anti-CD162 (Becton Dickinson), anti-CCR1, anti-CCR2, anti-CXCR5 (R&D Systems), or anti-CD62L, anti-CD126, anti-CD19, anti-CD95, anti-CD138, anti-CD28, anti-HLA DR (Coulter-Immunotech). Isotype-matched mouse mAbs were used as control.

Percentages of cells in the S-phase of the cell cycle were determined using propidium iodide, and data were analyzed with the ModFitLT software (Becton Dickinson). Apoptosis was evaluated with FITC-conjugated Annexin-V (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytospin smears of cell-sorted CD20−/CD38bright day 6 plasma cells were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa or fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes. Immunohistochemistry was performed with an automaton (Techmate 500; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) using anti-κ and anti-λ and revelation with DAB or Fast Red (DAKO).

For immunoglobulin quantification, B cells harvested on day 4 were seeded at 6 × 105/mL in RPMI–10% fetal calf serum in the presence of IL-2 + IL-10 + IL-12 + IL-6. Supernatants were harvested on day 11 of culture, and total immunoglobulin levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described.14 The number of cell-sorted CD20−/CD38bright plasma cells secreting immunoglobulin was determined by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT).15

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and was reverse transcribed with the Reverse Transcription System and an oligo (dT) primer (Promega, Madison, WI). The following primers were used: β2-microglobulin, 5′-CTCGCGCTACTCTCTCTTTCTGG-3′ and 5′-GCTTACATGTCTCGATCCCACTTAA-3′; PRDI-BF1, 5′-AGCTGACAATGATGAACTCA-3′ and 5′-CTTGGGGTAGTGAGCGTTGTA-3′; BSAP/Pax-5, 5′-CAACCAACCCGTCCAGCTTC-3′ and 5′-TCACAA TGGGGTAGGACTGCG-3′; XBP-1, 5′-TACACTGCCTGGAGGATAGC-3′ and 5′-GTTCCCGTTGCTTACAGAAG-3′; IRF-4, 5′-TGTGCCAGAGCAGGATCTAC-3′ and 5′-GGAATGGCGGATAGATCTGT-3′; gas6, 5′-CTGCCTCCAGATCTGCCACAAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTGGTGACACGGCCGAC-3′. For tumor antigens, we used the primers and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions previously described.16 PCR were performed with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, NJ), and the amplified products were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. RT-PCR using β2-microglobulin (β2 M) primers served as an internal standard. For the detection of gas6, radioactive RT-PCR was performed by adding 1 μCi (37 Bq) α32P-dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in each PCR reaction. Reaction products were electrophoresed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel, dried, and exposed to x-ray film.

Cell migration

The chemotaxis assay was performed in 5-μm pore transwell inserts as described.17 A total of 3 × 105PB B cells or 2 × 105 PPC or MM cell lines was added in 200 μL RPMI-1% human albumin to the upper chamber and allowed to migrate in response to macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3β or stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF)-1 (1000 ng/mL). After a 5-hour incubation at 37°C, cells that had migrated to the lower chamber were collected and counted microscopically.

Analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was converted to double-strand cDNA using a T7-polyT primer and the reverse transcriptase Superscript II (Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France), and this was subjected to in vitro transcription (Ambion, Austin, TX) in the presence of biotinylated UTP and CTP. Biotinylated RNA probes were applied to oligonucleotide HuGeneFL GeneChip arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Arrays were stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Fluorescence intensities were quantified and analyzed using the GeneChip software (Affymetrix). Arrays were scaled to an average intensity of 1500. A threshold of 60 was assigned to small and negative values as previously described, and data were normalized within samples to a median value of 100. Finally, genes that were absent across all the samples were removed so that 4860 genes were retained for analysis. Analysis was then performed using the Cluster and TreeView hierarchical clustering software developed by Eisen et al.18 Such clustering was previously demonstrated to successfully separate cancerous and noncancerous tissues from various origins.19 20

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test using SPSS software (SPSS Incorporated, Chicago, IL).

Results and discussion

Amplification and differentiation of peripheral blood B cells

To obtain a large number of PPCs, we optimized the culture conditions to amplify PB B cells and to trigger their differentiation into plasma cells. Starting with 100 mL blood, a mean number of 9.0 ± 2.6 × 106 CD19+CD20+ PB B cells were obtained with a purity of 96.8% ± 2.1%. We found that CD40L + IL-2 + IL-4 stimulation yielded a 2.0 ± 0.4-fold amplification of PB B cells after 4 days of culture (n = 5). Addition of IL-10 and IL-12 increased this rate of amplification by 135% (P = .008) in association with a significant increase in the percentage of cells in the S-phase (51% ± 5% vs 42% ± 7%;P = .03) and a low percentage of apoptotic cells (89% ± 2.6% Annexin V–negative cells). Addition of IL-10 or IL-12 alone was less potent than the combination of the 2 cytokines (data not shown). Thus, using CD40L + IL-2 + IL-4 + IL-10 + IL-12, it was possible to get approximately 30 × 106Annexin V–negative proliferating B cells from 100 mL blood.

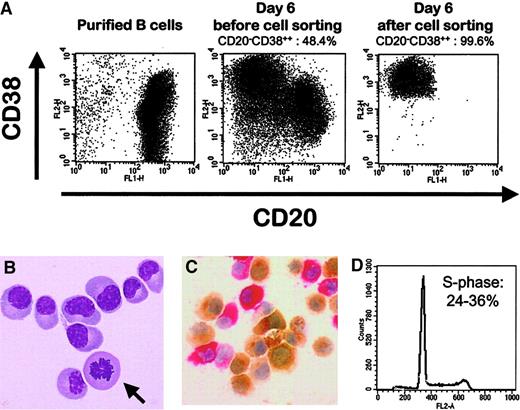

In agreement with previous data obtained with tonsillar B cells,4 removal of CD40 stimulation was necessary to drive the differentiation of amplified PB B cells into plasma cells (data not shown). We used IL-2 + IL-10 + IL-12 + IL-6 because all these cytokines had proved to be essential for the differentiation of tonsillar B cells into plasma cells.4-7 Approximately half the amplified B cells were induced to differentiate within 2 days into cells expressing no CD20 and a high density of CD38 (Figure1A). Starting with PB B cells from 10 healthy volunteers, the mean percentage of CD20−/CD38++ cells was 50% ± 7%, and the cell viability evaluated by lack of Annexin V staining was 74.6% ± 4.5% (Table 1). During this 2-day culture period, the cell number increased 3.2-fold. Combining the rates of amplification during the 2 culture steps, the overall amplification factor was 9.1 ± 2.7. Viable CD20−/CD38++ cells could be further selected using cytofluorometry cell sorting with a purity of more than 99% (Figure 1A) and a yield of purification of 40.5% ± 4.4% (n = 5). Day 6 CD20−/CD38++ cells were still highly proliferative, as shown by the presence of mitotic figures (Figure 1B). Mean percentage of CD20−/CD38++ cells in the S-phase was 30% ± 4% (n = 5) (Figure 1D). If the culture was prolonged for 2 additional days, the proportion of CD20−/CD38++ cells increased and reached more than 85%, but the cell viability decreased, as has already been indicated for plasma cells generated from tonsillar B cells and for polyclonal plasmablastic cells harvested from patients with RP.7,21,22 We then evaluated whether memory and naive B cells could be induced to differentiate into CD20−/CD38++ cells. Because CD27 is the most reliable marker of somatically mutated memory B cells,23CD19+CD27− and CD19+CD27+ B-cell subsets were purified and compared with the overall CD19+ compartment for their ability to generate CD20−/CD38++ cells. As shown in Figure 2, virtually all CD27+ postgerminal center B cells and no naive CD27− B cells differentiated into CD20−/CD38++ cells. These data strongly suggest that only CD27+ PB memory B cells, with somatically mutated immunoglobulin genes, are able to differentiate into CD20−/CD38++ cells.

Differentiation of peripheral blood B cells into polyclonal plasmablastic cells.

(A) Percentages of CD20−/CD38++ cells were evaluated on purified PB B cells, on unseparated cells obtained after the 2-step culture, and on sorted cells. Viable cells were gated by size and granulometry. (B) Giemsa staining of sorted CD20−/CD38++ cells showing their plasma cell morphology and a mitosis figure (arrow). Original magnification, × 1000. (C) Unseparated cells were stained with anti-κ (brown) and anti-λ (red) light chain. Original magnification, × 400. (D) Percentages of CD20−/CD38++ cells in the S-phase were determined using PI staining. They ranged from 24% to 36% in 5 separate experiments.

Differentiation of peripheral blood B cells into polyclonal plasmablastic cells.

(A) Percentages of CD20−/CD38++ cells were evaluated on purified PB B cells, on unseparated cells obtained after the 2-step culture, and on sorted cells. Viable cells were gated by size and granulometry. (B) Giemsa staining of sorted CD20−/CD38++ cells showing their plasma cell morphology and a mitosis figure (arrow). Original magnification, × 1000. (C) Unseparated cells were stained with anti-κ (brown) and anti-λ (red) light chain. Original magnification, × 400. (D) Percentages of CD20−/CD38++ cells in the S-phase were determined using PI staining. They ranged from 24% to 36% in 5 separate experiments.

Differentiation of amplified peripheral blood B cells into CD20−/CD38++ cells

| Healthy donors . | CD20−/ CD38++(%) . | Annexin-V (%) . | Amplification factor from day 4 to 6 . | Overall amplification factor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | 18 | 2.6 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 50 | 30 | 4.2 | 9.5 |

| 3 | 41 | 24 | 3 | 6.4 |

| 4 | 60 | 22 | 3.7 | 15.6 |

| 5 | 41 | 30 | 2.6 | 7.7 |

| 6 | 42 | 32 | 3 | 9 |

| 7 | 51 | 26 | 4 | 9.4 |

| 8 | 46 | 29 | 2.8 | 7.6 |

| 9 | 56 | 22 | 3.5 | 8 |

| 10 | 51 | 23 | 2.5 | 11 |

| Mean ± SD | 50 ± 7 | 25.6 ± 4.5 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 2.7 |

| Healthy donors . | CD20−/ CD38++(%) . | Annexin-V (%) . | Amplification factor from day 4 to 6 . | Overall amplification factor . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | 18 | 2.6 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 50 | 30 | 4.2 | 9.5 |

| 3 | 41 | 24 | 3 | 6.4 |

| 4 | 60 | 22 | 3.7 | 15.6 |

| 5 | 41 | 30 | 2.6 | 7.7 |

| 6 | 42 | 32 | 3 | 9 |

| 7 | 51 | 26 | 4 | 9.4 |

| 8 | 46 | 29 | 2.8 | 7.6 |

| 9 | 56 | 22 | 3.5 | 8 |

| 10 | 51 | 23 | 2.5 | 11 |

| Mean ± SD | 50 ± 7 | 25.6 ± 4.5 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 2.7 |

Purified peripheral blood B cells from 10 healthy donors were cultured for 4 days with CD40 + IL-2 + IL-4 + IL-10 + IL-12. Amplified B cells were then harvested, washed, and cultured for 2 additional days with IL-2 + IL-10 + IL-12 + IL-6. At day 6 of culture, the viability was evaluated by annexin V staining, and the percentage of CD20−/CD38++ plasma cells was determined by flow cytometry.

Differentiation of naive and memory B cells into polyclonal plasmablastic cells.

CD19+ B cells, CD19+CD27− naive B cells and CD19+CD27+ memory B cells were cell-sorted after double-staining with FITC-labeled anti-CD19 and PE-labeled anti-CD27 mAb. The 3 B-cell subsets isolated from the same donor were cultured as described in “Materials and methods,” and the percentage of CD20−/CD38++ cells was evaluated on day 6. Data shown are from 1 of 2 representative experiments.

Differentiation of naive and memory B cells into polyclonal plasmablastic cells.

CD19+ B cells, CD19+CD27− naive B cells and CD19+CD27+ memory B cells were cell-sorted after double-staining with FITC-labeled anti-CD19 and PE-labeled anti-CD27 mAb. The 3 B-cell subsets isolated from the same donor were cultured as described in “Materials and methods,” and the percentage of CD20−/CD38++ cells was evaluated on day 6. Data shown are from 1 of 2 representative experiments.

In conclusion, our study shows that it is possible to get approximately 12 × 106 viable and highly pure CD20−/CD38++ cells from 100 mL blood. Such results would, for the first time, allow a complete phenotypic, functional, and genetic characterization of these cells.

CD20−/CD38++ cells have the major biologic features of normal polyclonal plasmablastic cells

Purified CD20−/CD38++ cells have cytologic characteristics of normal plasmablastic cells that could be easily distinguished from purified PB B cells (Figure 1B). All the CD20−/CD38++ cells produced cytoplasmic κ or λ immunoglobulin light chain, with a κ/λ ratio of 2:1 as detected by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1C). Sixty percent of PPCs expressed IgM isotype, 25% IgA, less than 15% IgG, and 2% IgD (data not shown). IgM-bearing memory B cells were previously found to represent approximately 60% of CD27+ memory B cells in humans,23 and isotype switching was abolished in at least some of these IgM+ mutated B cells.23,9Because PPCs are generated from memory B cells, these data could explain why most PPCs were IgM+, unlike malignant plasma cells. Immunoglobulin secretion was confirmed by ELISA (77.06 ± 21.31 μg/mL polyclonal immunoglobulin in culture supernatant, n = 6) and ELISPOT (data not shown). Broad comparative analysis of previously reported phenotypes of normal plasma cell subsets with those of CD20−/CD38++ cells (Figure 3; Table2) shows that purified CD20−/CD38++ have the major characteristics of normal plasmablastic cells, close to those of tonsillar plasma cells or of the plasmablastic CD138− fraction of RP.21,24-28 CD20−/CD38++ cells expressed very low levels of CD21, CD22, and CD23 and a high level of CD27 (Figure 3). CD27 has recently been reported to be up-regulated during germinal center B-cell differentiation into plasma cells, so that a high expression of CD27 can be considered a specific marker for plasma cells.29 CD20−/CD38++cells lacked CD49e and expressed CD45 and CD95, as previously reported for tonsillar plasma cells and plasma cells from RP, unlike normal bone marrow plasma cells and mature myeloma cells (Table2).21,25,26,28,30 Moreover, CD138, the only differentiation antigen to distinguish plasma cells from plasmablasts,21 was expressed on only 13.7% ± 4.4% (n = 6) of day 6 polyclonal CD20−/CD38++cells (Figure 3C), unlike CD20+/CD38− cells that did not express CD138. Similarly, only 17% of plasma cells from RP are CD138+.21 On the contrary, normal bone marrow plasma cells and myeloma cells highly expressed CD138.31Thus, in vitro–generated CD20−/CD38++ cells have the major characteristics of tonsillar plasma cells or plasmablastic cells obtained from patients with reactional polyclonal plasmacytoses and are termed in the following PPCs.

Phenotypic changes during the differentiation of PB B cells into plasmablastic cells.

(A) Purified CD19+ PB B cells were single-stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD21, anti-CD22, anti-CD23, or anti-CD27 mAb. (B) By comparison, cells obtained on day 6 of the 2-step culture were stained with Cy chrome-labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38, and PE-labeled anti-CD21, anti-CD22, anti-CD23, or anti-CD27 mAb. Dotted lines, isotypic control; bold lines, CD20−/CD38++ cells; solid lines, CD20+/CD38+/− cells. (C) Expression of CD138 was evaluated using PE-conjugated anti-CD138 mAb on CD20−/CD38++ and CD20+/CD38+/− cells.

Phenotypic changes during the differentiation of PB B cells into plasmablastic cells.

(A) Purified CD19+ PB B cells were single-stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD21, anti-CD22, anti-CD23, or anti-CD27 mAb. (B) By comparison, cells obtained on day 6 of the 2-step culture were stained with Cy chrome-labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38, and PE-labeled anti-CD21, anti-CD22, anti-CD23, or anti-CD27 mAb. Dotted lines, isotypic control; bold lines, CD20−/CD38++ cells; solid lines, CD20+/CD38+/− cells. (C) Expression of CD138 was evaluated using PE-conjugated anti-CD138 mAb on CD20−/CD38++ and CD20+/CD38+/− cells.

Phenotype of CD20−CD38++ PPCs compared with B cells and with normal and tumor plasma cells

| . | B cells . | PPC . | Tonsillar plasma cells . | Bone marrow plasma cells . | Plasma cells from RP . | Myeloma plasma cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | ++ | + | + | + | + | − |

| CD20 | ++ | − | − | − | − | − |

| CD21 | ++ | + weak | + weak | + weak | − | ± |

| CD22 | ++ | − | − | − | ± | − |

| CD23 | ++ | + weak | − | − | − | − |

| CD27 | ± | ++ | ++ | ++ | ND | ± |

| CD28 | − | − | − | − | ± (1%-12%) | ± |

| CD38 | ± | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD45 | + | + | + | ± | + | ± |

| CD49e | − | − | − | ± | − | ± |

| CD95 | ± | + | + | − | + | ± |

| CD138 | − | ± (9%-20%) | ± | + | ± (6%-50%) | + |

| HLA DR | ++ | + | + | + | + | − |

| . | B cells . | PPC . | Tonsillar plasma cells . | Bone marrow plasma cells . | Plasma cells from RP . | Myeloma plasma cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | ++ | + | + | + | + | − |

| CD20 | ++ | − | − | − | − | − |

| CD21 | ++ | + weak | + weak | + weak | − | ± |

| CD22 | ++ | − | − | − | ± | − |

| CD23 | ++ | + weak | − | − | − | − |

| CD27 | ± | ++ | ++ | ++ | ND | ± |

| CD28 | − | − | − | − | ± (1%-12%) | ± |

| CD38 | ± | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| CD45 | + | + | + | ± | + | ± |

| CD49e | − | − | − | ± | − | ± |

| CD95 | ± | + | + | − | + | ± |

| CD138 | − | ± (9%-20%) | ± | + | ± (6%-50%) | + |

| HLA DR | ++ | + | + | + | + | − |

Fluorescence staining and analysis of PPC were performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Phenotype of B cells, tonsillar plasma cells, bone marrow plasma cells, plasma cells from RP, and myeloma plasma cells were described elsewhere. For myeloma cells, when the marker was expressed by less than 10% of the patients, it was considered negative.

ND indicates not done.

Transcription factors involved in the in vitro differentiation of B cells into PPCs

Four transcription factors have been recently identified in the control of B-cell differentiation into plasma cells.32 The positive regulatory domain I–binding factor 1 (PRDI-BF1) and X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) are the major transcription factors involved in plasma cell development. Ectopic expression of Blimp-1, the murine homologue of PRDI-BF1, is sufficient to drive the differentiation of a murine lymphoma cell line into plasma cells.33 PRDI-BF1 is also up-regulated during the differentiation of human B cells into plasma cells.34Recently, XBP-1 was shown to be mandatory for the terminal differentiation of B cells into plasma cells.35 In addition, interferon regulatory protein 4 (IRF-4) expression is restricted to plasmablasts and mature plasma cells among the B-cell lineage,36 and IRF-4 favors plasma cell differentiation. We reported that PRDI-BF1, XBP-1, and IRF-4 were all up-regulated in the CD20−/CD38++ PPCs compared with purified PB B cells (Figure 4). On the contrary, BSAP/Pax-5 is expressed in normal B cells and is down-regulated in normal and malignant plasma cells.37,38 BSAP/Pax-5 overexpression is sufficient to suppress differentiation of a late B-cell line into plasma cells,39 perhaps through the repression of XBP-1 expression.40 We found here that BSAP/Pax-5 was down-regulated in PPCs compared with PB B cells (Figure4). In conclusion, unlike BSAP/Pax-5, CD20−/CD38++ PPCs express PRDI-BF1, XBP-1, and IRF4.

Expression of the major transcription factors involved in the in vitro differentiation of B cells into plasmablastic cells.

RT-PCR for BSAP/Pax-5, PRDI-BF1, IRF-4, and XBP-1 were performed on purified PB B cells (B, lanes 1 and 2), on purified plasma cells from a patient with reactive plasmacytosis (RP, lane 3), and on CD20−/CD38++ sorted polyclonal plasmablastic cells (PPC, lanes 4-6).

Expression of the major transcription factors involved in the in vitro differentiation of B cells into plasmablastic cells.

RT-PCR for BSAP/Pax-5, PRDI-BF1, IRF-4, and XBP-1 were performed on purified PB B cells (B, lanes 1 and 2), on purified plasma cells from a patient with reactive plasmacytosis (RP, lane 3), and on CD20−/CD38++ sorted polyclonal plasmablastic cells (PPC, lanes 4-6).

Generation of polyclonal plasmablastic cells from PB B cells from MM patients

We investigated whether polyclonal CD20−/CD38++ PPCs could also be obtained from PB B cells from MM patients. The general consensus is that at least a minority of malignant clonal PB B cells are present in MM patients.41,42 These cells harbor the same immunoglobulin light-chain isotype as the tumor clone plasma cells.43 We therefore purified κ+ CD19+ cells from 4 patients with a λ light chain MM and λ+CD19+ cells from one patient with κ light chain MM to avoid any contamination of the normal plasmablastic cells with the tumor compartment. Plasmablastic CD20−/CD38++cells can be generated from these κ+ or λ+B cells with an overall amplification factor of 13.2 ± 4.1. Mean percentage of CD20−/CD38++ cells, cell viability, and cytologic and phenotypic features of cell-sorted PPCs generated from MM patients were similar to those generated from healthy volunteers (data not shown). Their immunoglobulin secretion was strictly restricted to κ or λ light chain, thus proving the absence of tumor plasma cell in the PPC population (data not shown). These results demonstrate for the first time that it is possible to generate normal plasmablastic cells from PB B cells of patients with MM. These data have several major implications for the understanding of MM pathogenesis. First, this demonstrates that there is no intrinsic defect of nonmalignant PB B cells from MM patients to differentiate into plasma cells in vitro, given that the appropriate signals are provided. Thus, the decrease in circulating polyclonal immunoglobulin levels in MM patients should be caused mainly by the difficulty for normal plasma cells to seed into the bone marrow environment rather than to a blockade of normal B-cell differentiation. Second, this model would allow the identification of gene expression alterations involved in MM pathogenesis by comparing normal and malignant plasma cells from the same patient. Microarray technology provides a valuable tool to rapidly pinpoint such genetic changes. Third, this in vitro model of B-cell differentiation into plasmablastic cells can be useful in investigating the oncogenic potential of the genes that are dysregulated in myeloma cells, in particular through gene transfer into these highly proliferative cultured cells.

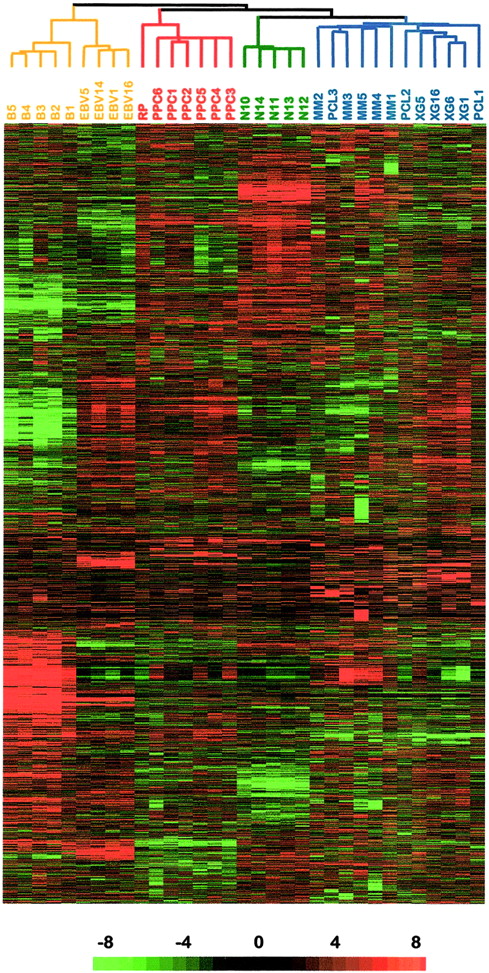

Gene expression patterns of CD20−/CD38++plasma cells

The gene expression profile of cell-sorted CD20−/CD38++ PPCs was studied using the Affymetrix oligonucleotide HuGeneFL arrays. It was compared with those of purified plasma cells from one RP, normal plasma cells purified from bone marrow, primary tumor plasma cells, human MM cell lines, and purified PB B cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines. In this study, 3 autologous pairs (malignant plasma cells and autologous normal plasmablastic cells) were obtained from 3 different patients: PPC4/MM3, PPC5/MM5, PPC6/MM4. Through the use of a hierarchical clustering algorithm, 4680 genes were used to cluster the 33 samples on the basis of similarities in their patterns of gene expression. Figure5 provides an overview of the variation in gene expression across these samples. The algorithm segregated EBV cell lines and PB B cells into a major “B-cell cluster” and the malignant and nonmalignant plasma cells in a major “plasma-cell cluster,” showing that in vitro–generated PPCs were more similar to plasma cell expression patterns than normal B cells. The “plasma-cell cluster” can be further divided into 2 sub-branches, one comprising RP and PPCs and one made up of normal bone marrow plasma cells and myeloma cells. PPCs obtained from myeloma patients (PPC4, PPC5, PPC6) segregated together and were intermingled with PPC obtained from healthy donors (PPC1, PPC2, PPC3), thus proving that they represent a normal plasmablastic compartment. A complete data set table listing expression data for the 5 normal bone marrow plasma cells as well as data obtained for the 28 remaining samples are available at http://lambertlab.uams.edu. Thus, this hierarchical clustering confirms that the in vitro–generated PPCs are close to plasmablastic cells and plasma cells, in agreement with the phenotypic and RT-PCT data presented above. Comprehensive evaluation of the gene expression patterns differentiating PPCs, tonsillar PCs, and bone marrow PCs is in progress and will be reported in the next year.

Hierarchical clustering of gene expression data.

Five purified PB B cells (B1 to B5), 4 lymphoblastoid B cell lines (EBV-1, EBV-5, EBV-14, and EBV-16), 8 primary myeloma samples (MM1 to MM5 and PCL1 to PCL3), 4 MM cell lines (XG-1, XG-5, XG-6, and XG-16), and purified polyclonal plasma cells from 1 patient with reactive plasmacytosis (RP), 6 purified PPC samples (PPC1 to PPC6), and 5 normal bone marrow–derived plasma cells were studied using the Affymetrix HuGeneFL array. Each row represents a single gene and each column a single sample. The relative expression of each gene was visualized with color variation from green (weak expression) to red (high expression). Black indicates median expression.

Hierarchical clustering of gene expression data.

Five purified PB B cells (B1 to B5), 4 lymphoblastoid B cell lines (EBV-1, EBV-5, EBV-14, and EBV-16), 8 primary myeloma samples (MM1 to MM5 and PCL1 to PCL3), 4 MM cell lines (XG-1, XG-5, XG-6, and XG-16), and purified polyclonal plasma cells from 1 patient with reactive plasmacytosis (RP), 6 purified PPC samples (PPC1 to PPC6), and 5 normal bone marrow–derived plasma cells were studied using the Affymetrix HuGeneFL array. Each row represents a single gene and each column a single sample. The relative expression of each gene was visualized with color variation from green (weak expression) to red (high expression). Black indicates median expression.

To highlight in more detail the genes involved in the process of B-cell differentiation into PPCs, we first established an ordered list of the genes that were differentially expressed between the B-cell samples (purified B cells and EBV cell lines) and the PPC samples (PPC and RP). EBV cell lines were included to eliminate mainly cell cycle genes because PPCs are highly proliferating, contrary to PB B cells (Figure1D). We then also identified the genes that were differentially expressed between the MM samples (primary tumor plasma cells and myeloma cell lines) and the PPC samples. For each gene, we defined 3 ratios: mean in PPC-to-mean in B cells (PPC:B ratio), mean in B cells-to-mean in PPC (B:PPC ratio), and mean in MM-to-mean in PPC (MM:PPC ratio). We retained only the genes that significantly varied among the different groups of samples (P ≤ .05, Mann-Whitney nonparametric test) and that had a ratio greater than 3. Selected genes were then ordered from the highest ratio to the lowest.

Genes differentially expressed in normal plasmablastic cells versus B cells

The 50 genes that have the highest PPC:B ratio and the 50 genes that have the highest B:PPC ratio are listed on our Web site (http://www.u475.montp.inserm.fr), and a selection of the most relevant genes is provided in Table 3. Within this selection, several genes up-regulated in PPCs validated the data obtained with the Affymetrix microarray, especially CD38 because PPCs have been sorted on the basis of a high CD38 expression, CD27 because we have demonstrated that the level of CD27 was higher in PPCs than in naive and memory B cells, and 10 immunoglobulin sequences because a high level of immunoglobulin mRNA associated with immunoglobulin secretion is one of the major features of plasma cells. Conversely, the down-regulation of CD20, CD21, HLA class 2, and CD69 during maturation of B cells into PPCs is in good agreement with the previously reported phenotype of B cells and plasma cells.

Genes differentially expressed between PPC and B cells

| Name . | Probe set . |

|---|---|

| Genes with the highest PPC:B ratio | |

| Gas6(174) | L13720 |

| CCR2 (41) | U95626 |

| IL6R (15) | M20566 |

| CD38(14) | D84276 |

| CD162/SELPLG (11) | U25956 |

| XBP1 (7) | M31627 |

| BCMA (7) | Z29574 |

| CD27 (5) | M63928 |

| Genes with the highest B:PPC ratio | |

| CD20 (181) | X12530 |

| HLA-DQA1 (39) | M17236 |

| CD69(25) | Z30426 |

| CIITA (19) | X74301 |

| Bin1 (16) | U68485 |

| Bcl2-related protein A1 (14) | U29680 |

| Blk (14) | S76617 |

| HLA-DQB1 (14) | K02405 |

| CCR7(13) | L31584 |

| HLA-DPB1 (13) | M83664 |

| CD21 (13) | M26004 |

| Name . | Probe set . |

|---|---|

| Genes with the highest PPC:B ratio | |

| Gas6(174) | L13720 |

| CCR2 (41) | U95626 |

| IL6R (15) | M20566 |

| CD38(14) | D84276 |

| CD162/SELPLG (11) | U25956 |

| XBP1 (7) | M31627 |

| BCMA (7) | Z29574 |

| CD27 (5) | M63928 |

| Genes with the highest B:PPC ratio | |

| CD20 (181) | X12530 |

| HLA-DQA1 (39) | M17236 |

| CD69(25) | Z30426 |

| CIITA (19) | X74301 |

| Bin1 (16) | U68485 |

| Bcl2-related protein A1 (14) | U29680 |

| Blk (14) | S76617 |

| HLA-DQB1 (14) | K02405 |

| CCR7(13) | L31584 |

| HLA-DPB1 (13) | M83664 |

| CD21 (13) | M26004 |

Genes are listed from the highest ratio to the lowest. Genes coding for immunoglobulin sequences have been omitted.

Affymetrix microarrays also confirmed the overexpression of plasma cell transcription factor XBP-1 in PPCs and in tumor plasma cells compared with B cells. IRF-4 was also up-regulated 4-fold in PPC compared with PB B cells (P = .003), again in good agreement with our RT-PCR data (Figure 4). However, this gene was not listed in Table 3because it was also overexpressed in EBV cell lines. A probe for the second major plasma cell transcription factor, PRDI-BF1, was not included in the Affymetrix microarray. Conversely, the B-cell–specific Src kinase, Blk, was overexpressed in B cells, unlike in plasma cells. This is in agreement with the role of BSAP/Pax5 in the activation of the Blk gene44 and the repression of theXBP-1 gene.40 Similarly, the genes coding for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class 2 transactivator (CIITA) transcription factor and the bcl2-family protein A1 were down-regulated in PPCs compared with B cells. The down-regulation of CIITA and A1 genes in PPCs may be explained by the up-regulation of the PRDI-BF1 gene (Figure 4). Indeed, an ectopic expression of PRDI-BF1 directly represses the CIITA promoter,45 thus leading to the extinction of MHC class 2 expression, and it induces a reduction of the A1 level,46 in association with an apoptotic phenotype.

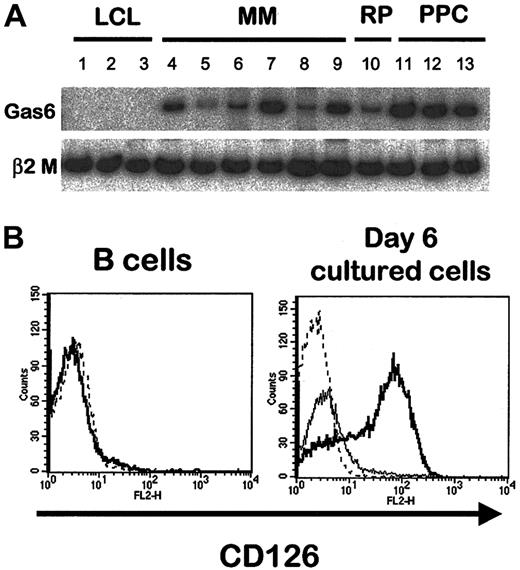

Importantly, 3 genes coding for growth factors or growth factor receptors were found among the 50 genes with the highest PPC:B ratios. They code for proteins that can be involved in normal plasma cell differentiation and in MM pathogenesis because they were highly expressed in polyclonal and tumor plasma cells. The first one is Gas6, a factor of the vitamin K–dependent protein family that is the ligand for Axl, Tyro3, and Mer tyrosine kinase receptors. Gas6 induces a mitogenic signal in some Tyro3- or Axl-expressing cell lines. Moreover, it stimulates mature osteoclast activity and has been involved in the bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency.47 The expression of gas6 gene in normal and malignant plasma cells, unlike B cells, was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (Figure6A). Recently, we described an expression of Tyro3 in some MM samples and normal plasma cells.11Together, these data suggest that Gas6 can contribute by an autocrine or paracrine loop to the biology of normal and tumor plasma cells. The second gene coding for growth factors and growth factor receptors that is up-regulated in PPCs is the IL-6 receptor α-chain (IL6R)/CD126 gene. An increased expression of IL-6R/CD126 protein on PPCs compared to B cells was also demonstrated by FACS analysis (Figure 6B). IL-6 was recently found to be a growth factor for nonmalignant human plasmablasts in association with an up-regulation of CD126 during in vitro differentiation of memory tonsillar B cells into plasma cells.7 In addition, IL-6 plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of MM, and several therapeutic strategies focused on blocking the IL-6 pathway have been developed in this disease.48,49 The third growth factor/growth factor receptor–coding gene was the TNF receptor superfamily member BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen). BCMA is one of the receptors for the B-cell activation factor from the TNF family (BAFF, also known as BLys), a costimulator of B-cell survival and proliferation produced by monocytes, dendritic cells, and activated T cells, and a proliferation-inducing ligand, or APRIL, which is produced only in tumor tissues and which stimulates the growth of transformed tumor cell lines.50 Until now, BCMA expression has been reported to be tightly restricted to mature CD19+ B cells. Our data suggest that BCMA expression can be involved in normal and malignant plasma cell biology. A soluble form of BCMA can interfere with tumor cell proliferation in a murine carcinoma model51 and could thus be an interesting new antimyeloma drug.

Growth factors and growth factor receptors in B cells and PPC.

(A) Radioactive RT-PCR for gas6 in EBV-1 (lane 1), EBV-5 (lane 2), EBV-16 (lane 3), XG-1 (lane 4), XG-6 (lane 5), XG-16 (lane 6), MM1 (lane 7), MM2 (lane 8), MM3 (lane 9), RP (lane 10), and PPC1 to PPC3 (respectively, lanes 11 to 13). (B) Purified CD19+ PB B cells were single-stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD126 mAb (left). Dotted line indicates isotypic control. By comparison, cells obtained on day 6 of culture were stained with Cy chrome–labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38, and PE-labeled anti-CD126 mAb (right). Dotted line indicates isotypic control; bold line, CD20−/CD38++ cells; solid line, CD20+/CD38+/− cells.

Growth factors and growth factor receptors in B cells and PPC.

(A) Radioactive RT-PCR for gas6 in EBV-1 (lane 1), EBV-5 (lane 2), EBV-16 (lane 3), XG-1 (lane 4), XG-6 (lane 5), XG-16 (lane 6), MM1 (lane 7), MM2 (lane 8), MM3 (lane 9), RP (lane 10), and PPC1 to PPC3 (respectively, lanes 11 to 13). (B) Purified CD19+ PB B cells were single-stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD126 mAb (left). Dotted line indicates isotypic control. By comparison, cells obtained on day 6 of culture were stained with Cy chrome–labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38, and PE-labeled anti-CD126 mAb (right). Dotted line indicates isotypic control; bold line, CD20−/CD38++ cells; solid line, CD20+/CD38+/− cells.

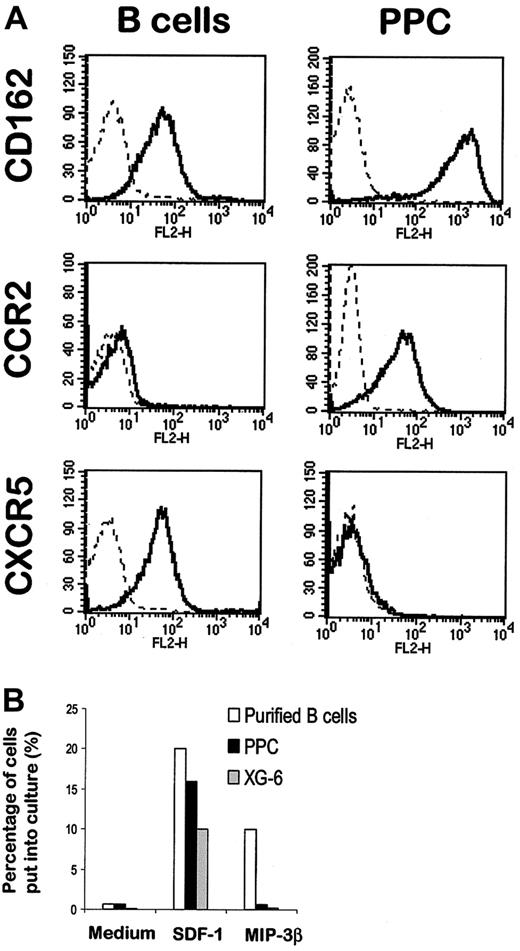

Tumor and malignant plasma cells overexpressed 2 genes coding for homing molecules: CD162, the P-selectin glycoprotein ligand, and CC chemokine receptor (CCR)2, the receptor for the inflammatory chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1. Overexpression of these 2 homing proteins on normal plasma cells was confirmed by FACS analysis (Figure7A). CD162 is involved in the adhesion of myeloid and lymphoid cells to P-selectin. Recently, several studies have demonstrated that CD162 is poorly expressed on PB or tissue B cells but is present at a high level on tonsillar plasma cells,52 in agreement with our current data. The expression of CCR2 on MM cells was also recently described by us and by other groups.11 53 Because MCP-1 is produced by bone marrow stromal cells, the specific expression of CCR2 on plasma cells can be involved in their homing in bone marrow. Four chemokines that drive B-lymphocyte migration are known to be constitutively expressed in secondary lymphoid organs: B cell–attracting chemokine (BCA)-1, which binds to the CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR)5 (also called Burkitt lymphoma receptor 1 [BLR1]); secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC, or 6C-kine) and MIP-3β, both binding to CCR7; and SDF-1, which is the ligand for CXCR4. PPCs poorly expressed genes coding for CXCR5 and CCR7 (data not shown and Table 3). The lack of expression of CXCR5 on PPC, unlike B cells, was confirmed using FACS analysis (Figure 7A). Because no reliable antibody specific for CCR7 was commercially available, we performed chemotaxis experiments with MIP-3β. In keeping with gene expression data, only purified B cells migrated in response to the MIP-3β CCR7 ligand (Figure 7B). The CXCR4 ligand SDF-1 was used as a positive control because the CXCR4 gene was expressed in all samples (see complete data on our Web site). As shown in Figure 7B, B cells, normal PPCs, and malignant plasma cells were all efficiently attracted by SDF-1.

Expression of homing molecules in B cells and PPCs.

(A) Purified PB B cells (left panel) were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD162, anti-CCR2, or anti-CXCR5 mAb. PPCs were generated with the 6-day culture process described above and were stained with Cy chrome–labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38 and PE-conjugated anti-CD162, anti-CCR2, or anti-CXCR5 mAb. The right panel shows the expression of the homing molecules on gated CD20−/CD38++ cells. (B) Cell migration of B cells, PPCs, and tumor plasma cells. Purified B cells, XG-6 myeloma cell line, and sorted CD20−/CD38++ PPCs were seeded in the upper chamber of a Transwell with SDF-1 or MIP-3β in the lower chamber. Results are expressed as the percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber.

Expression of homing molecules in B cells and PPCs.

(A) Purified PB B cells (left panel) were stained with a PE-conjugated anti-CD162, anti-CCR2, or anti-CXCR5 mAb. PPCs were generated with the 6-day culture process described above and were stained with Cy chrome–labeled anti-CD20, FITC-labeled anti-CD38 and PE-conjugated anti-CD162, anti-CCR2, or anti-CXCR5 mAb. The right panel shows the expression of the homing molecules on gated CD20−/CD38++ cells. (B) Cell migration of B cells, PPCs, and tumor plasma cells. Purified B cells, XG-6 myeloma cell line, and sorted CD20−/CD38++ PPCs were seeded in the upper chamber of a Transwell with SDF-1 or MIP-3β in the lower chamber. Results are expressed as the percentage of input cells that migrated to the lower chamber.

This brief description of the genes regulated in PPCs compared to B cells illustrates the ability of microarray technology to identify major intercellular communication signals, transduction, or metabolic pathways involved in the poorly understood plasma cell differentiation process. Little information is available on plasma cell differentiation given the very low frequency of normal plasma cells in vivo. In particular, it will be important to understand the relationship between the proliferative but short-lived plasmablastic cells generated in vitro or obtained from patients with RP and the nondividing but long-lived mature plasma cells found in bone marrow and spleen. In a later study, we will compare the gene expression profiles of various normal plasma cell subsets (PPCs, tonsillar, bone marrow), myeloma cells, and PB B cells (manuscript in preparation).

Genes overexpressed in tumor versus normal plasmablastic cells

In a recent study using a large number of samples from patients with newly diagnosed MM, Zhan et al12 identified 70 genes that were up-regulated and 50 genes that were down-regulated in myeloma cells compared with normal bone marrow plasma cells.12 We have listed the 50 genes that were the most overexpressed in MM cells compared with PPCs (see our Web site). A short list of the most relevant genes is given in Table 4. Although the number of patient samples used in this study was relatively small, several genes, in particular c-myc, and cyclin D1, pinpointed in the study of Zhan et al,12 were also found to be overexpressed in our MM samples when compared to PPCs. In addition, GCN5, a histone acetyltransferase recruited by c-myc and whose activity plays an essential role in the regulation of the transcription of myc target genes,54 was also found to be statistically up-regulated in tumor versus normal plasma cells with a ratio of 3.7 (data not shown), as previously reported by Zhan et al.12 Finally, we report here for the first time that MSSP, which stimulates the transforming activity of myc,55 was overexpressed in malignant plasma cells compared with normal plasma cells. Collectively, these data emphasize the major role of the c-myc pathway in myeloma malignant transformation.

Genes overexpressed in tumor versus normal plasmablastic cells

| Genes with the highest MM:PPC ratio . | |

|---|---|

| Name (MM:PPC ratio) . | Probe set . |

| Cyclin D1 (137) | X59798 |

| GAGE 6 (36) | U19147 |

| MAGE 3 (24) | U03735 |

| MAGE 1 (19) | M77481 |

| MAGE 2 (10) | L18920 |

| c-myc (8) | L00058 |

| RBMS1/MMSP(7) | HT2735 |

| SSX2 (7) | Z49105 |

| Genes with the highest MM:PPC ratio . | |

|---|---|

| Name (MM:PPC ratio) . | Probe set . |

| Cyclin D1 (137) | X59798 |

| GAGE 6 (36) | U19147 |

| MAGE 3 (24) | U03735 |

| MAGE 1 (19) | M77481 |

| MAGE 2 (10) | L18920 |

| c-myc (8) | L00058 |

| RBMS1/MMSP(7) | HT2735 |

| SSX2 (7) | Z49105 |

Genes are listed from the highest ratio to the lowest. Genes coding for immunoglobulin sequences have been omitted.

One of our goals in comparing the transcriptome of myeloma cells to normal plasma cells is to identify myeloma-specific tumor antigens. Of interest, 5 cancer-testis tumor antigens were present among the 50 “myeloma genes”: GAGE 6, MAGE 3,MAGE 1, MAGE 2, and SSX2. In fact, gene expression analysis of more than 100 patients with newly diagnosed MM has shown that MAGE 3 and MAGE 1 expression can account for all MAGE-positive cases, which represent 25% of the cases (J.S., unpublished data, January 2002). Cancer-testis antigens are particularly suitable for immunotherapy purposes because they are shared by many different patients and are strictly tumor specific. RT-PCR studies have recently demonstrated that MAGE andGAGE genes are expressed in myeloma cells, in particular from patients with advanced myeloma and in MM cell lines.16,56 These results were confirmed here using the Affymetrix microarray and RT-PCR analysis (Figure8A). In addition, we reported an overexpression of the SSX family members SSX1, SSX2, SSX4, and SSX5 by myeloma cells. SSX3 was not detected, as previously reported for other cancers (data not shown).57 Because SSX1 seemed to be the most frequently expressed SSX member, its expression was further studied using RT-PCR on a panel of 13 myeloma cell lines, 5 plasma cell leukemias in relapse, and 12 purified bone marrow tumor plasma cells from patients at diagnosis (Figure 8B). As described for the other cancer-testis tumor antigens, SSX1 expression was detected in most myeloma cell lines (10 of 13) and plasma cell leukemias (5 of 5) but was less frequent at the medullary stage of the disease (4 of 12).

Expression of cancer-testis genes in PPCs and tumor plasma cells.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of tumor-antigen expression in XG-1 (lane 1), XG-6 (lane 2), XG-16 (lane 3), MM1 (lane 4), MM2 (lane 5), MM3 (lane 6), B1 to B3 (respectively, lanes 7 to 9), PPC1 to PPC3 (respectively, lanes 10 to 12), EBV-1 (lane 13), EBV-5 (lane 14), and EBV-16 (lane 15). (B) RT-PCR for SSX1 on a panel of 13 HMCLs, 5 plasma cell leukemias, and 12 purified myeloma samples at diagnosis.

Expression of cancer-testis genes in PPCs and tumor plasma cells.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of tumor-antigen expression in XG-1 (lane 1), XG-6 (lane 2), XG-16 (lane 3), MM1 (lane 4), MM2 (lane 5), MM3 (lane 6), B1 to B3 (respectively, lanes 7 to 9), PPC1 to PPC3 (respectively, lanes 10 to 12), EBV-1 (lane 13), EBV-5 (lane 14), and EBV-16 (lane 15). (B) RT-PCR for SSX1 on a panel of 13 HMCLs, 5 plasma cell leukemias, and 12 purified myeloma samples at diagnosis.

Finally, several genes found to be up-regulated in myeloma cells compared with bone marrow plasma cells12 were also highly expressed in PPCs and vice versa. Some genes overexpressed in myeloma samples compared with PPCs were actually mature plasma cell genes. This highlights the interest of using various subsets of normal plasma cells to better delineate the true myeloma genes.

Conclusion

We describe here a model that makes it possible to obtain CD20−/CD38++ cells with all the morphologic, phenotypic, and functional features of polyclonal plasmablastic cells. With complete knowledge of the human genome and rapid improvement of the DNA chip technology, our model should be useful in bringing about a full understanding of the gene expression regulation that leads to normal terminal B-cell differentiation and the alterations that lead to neoplasia.

Because MM is a heterogeneous disease,12 it would be important to compare gene expression profiles of tumor plasma cells with those of several normal plasma cell compartments, including plasmablastic cells. In addition, the possibility of generating reproducibly a high number of proliferative plasma cells will allow the study of the biologic relevance of the genes dysregulated in myeloma cells. Finally, the detection of several cancer-testis genes among the so-called myeloma genes demonstrates that expression profiling may be an efficient approach to identifying new tumor antigens, as recently suggested in a murine model.58 The knowledge of oncogenic pathways and tumor-specific antigens will be a source of new therapeutics to improve the clinical outcome of this still fatal B-cell malignancy.

We thank Dr Jean-Pierre Vendrell for the ELISPOT experiments and Christophe Duperray for cell sorting.

Supported by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée).

K.T. and J.D. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Bernard Klein, INSERM U475, 99 rue Puech Villa, 34197 Montpellier, France; e-mail: klein@montp.inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal