Abstract

The human T-cell leukemia virus HTLV-I is a transfusion-transmissible retrovirus targeting T lymphocytes for which screening is not currently undertaken in United Kingdom blood donors. The introduction of universal leukocyte depletion (LD) of the United Kingdom blood supply raises the question as to the degree of protection afforded by this procedure against HTLV-I transmission by blood components. HTLV-I viral DNA removal by leukocyte-depleting filters was assessed in units of whole blood and platelets by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and by nested PCR for HTLV-I Tax DNA. We examined HTLV-I removal by LD filters using a model system of blood units containing exogenous spiked HTLV-I–positive MT-2 cells at a relevant concentration and whole blood donations from asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers. T-lymphocyte removal was assessed in parallel by measurement of endogenous subset-specific CD3 mRNA. In the MT-2 model system we observed 3.5 log10 to 4 log10 removal of HTLV-I Tax DNA by filtration of whole blood and 2 log10 to 3 log10 removal across platelet filters with 13 of 16 whole blood and 8 of 8 platelet units still positive after filtration. Despite 3 log10 to 4 log10 viral removal, HTLV-I Tax DNA could be detected after whole blood filtration in asymptomatic carriers with viral loads above 108 proviral DNA copies/L. T-lymphocyte removal was also between 3.5 log10 and 4.5 log10. HTLV-I provirus removal was incomplete in the model system and in asymptomatic carriers with viral loads greater than 108 copies/L. These results suggest that LD alone may not provide complete protection from HTLV-I transmission by transfusion.

Introduction

The human T-cell leukemia virus HTLV-I is endemic mainly in Japan, West Africa, and the Caribbean,1 while HTLV-II is mainly found in the Americas. Both viruses are integrated into the T-cell genome. HTLV-I infection is associated with a lifetime risk of 1% to 5% of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL),2 and a 3% lifetime risk of HTLV-I–associated myelopathy (HAM).3 Both HTLV-I and HTLV-II are found in Europe in migrants from endemic areas, and transmission through sexual contact, needle sharing, and blood transfusion is reported throughout Europe. Seropositivity rates in European blood donors range from less than 0.001% to 0.03%.4 The United Kingdom does not screen blood donors for antibodies to HTLV, but pilot studies have demonstrated overall seropositivity rates of 0.0013%5 to 0.005%,6which is 10 times lower than rates among pregnant women in the same regions.7 This is probably because of exclusion of high-risk groups including drug users and underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in the donor population. A recent study of Afro-Caribbean donors in the United Kingdom has shown prevalence of 0.11% to 0.55%.8

In countries that have introduced HTLV screening of blood donors, look-back studies have shown transmission to 13% to 28% of recipients of HTLV-positive red cell transfusions strongly associated with blood units in the first 14 days of shelf life.9,10 Platelets prepared from the same donors with a 5-day storage at 20°C had higher transmission rates of 25% to 75%.9,11 In contrast, fresh frozen plasma9-11 and plasma fractions12 have never been shown to transmit HTLV. At least 2 cases of transfusion-transmitted HTLV-I have occurred in the United Kingdom.13,14 Cases of both ATL and HAM following transfusion-acquired HTLV-I infection have been reported. Two immunosuppressed patients who received multiple HTLV-I–infected transfusions in Taiwan developed ATL 6 months and eleven years, respectively, after transfusion.15 ATL has also been reported in a patient treated for Hodgkin disease following HTLV seroconversion after blood transfusion16 and in 2 children who developed ATL following neonatal blood transfusion.17However, no cases of ATL were seen during a 15-year follow-up of 102 cases infected by transfusion in Japan.18 The association of HAM with transfusion-acquired infection is well documented19; HAM was seen in 1 patient in the aforementioned Japanese cohort with 2 further transfusion-related, rapid-onset cases of HAM in immunodeficient recipients reported in Europe.14,20 The incidence of HAM in Japan declined following the introduction of universal donor screening for HTLV-I.18

The association of infectivity with fresh cellular components raises the possibility that transmission of HTLV by transfusion requires viable T lymphocytes and that their removal from blood donations may clear the potentially infectious cells. Since 1999, the entire United Kingdom blood supply has been subjected to a leukocyte-depletion step, mainly by filtration, as a precaution against transmission of variant Creutzfeld-Jacob disease. This reduces the total leukocyte load in each donation by 3 log10 to 4 log10, to a residual count of less than 5 × 106 leukocytes/unit in greater than 99% of units with 95% confidence (National Blood Service data; Beckman N, manuscript submitted). We have therefore examined removal of HTLV-I and CD3-positive T cells by current leukocyte-depletion techniques using a human HTLV-I–carrying T-cell line to spike donations prior to filtration. We compared these results with the removal of HTLV-I provirus and CD3 mRNA after leukocyte depletion of blood taken from asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers with a range of proviral loads.

Materials and methods

Filtration of blood components containing MT-2 cell line

MT-2 is a human leukemic–derived T-cell line containing at least 8 integrated copies of the HTLV-I provirus per cell.21 Cultured cells were washed and added to pooled pairs of ABO identical citrated whole blood donations (final volume 513 mL ± 50 mL) to a concentration of 2 × 106 MT-2 cells/L, increasing the total number of T cells by less than 0.3%. The pool was divided equally and one unit of each pair was passed through a Pall WBF-2 filter, (Pall Biomedical, Portsmouth, United Kingdom), and the other through a Baxter RZ2000 filter (Baxter Heathcare, Egham, United Kingdom). Four pairs of units were filtered on day 0 (defined as the day of collection) at ambient temperature after a minimum 2 hours storage time, and a further 4 pairs were filtered on day 1 after storing the blood packs at 4°C overnight. Whole blood units were processed to plasma and red cell concentrates by standard separation procedures.

In a paired-study design, platelet concentrates were prepared from the pools of 8 buffy coats according to the standard National Blood Service “top and bottom” processing method.22 MT-2 cells were added to a concentration of 2 × 106/L into the buffy coat pool, which was then processed to yield platelet concentrate, divided, and passed through either Pall Autostop or Baxter PLX-5 filters. Each filter type was tested 4 times. Total leukocytes were enumerated in prefiltration and postfiltration samples by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry using TruCount beads according to manufacturer's instructions (Leucocount Kit, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). This technique has a sensitivity of 1 leukocyte/μL.

Prescreening and filtration of blood from asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers

To quantify HTLV-I viral load in asymptomatic carriers, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained by density gradient centrifugation. DNA was extracted and replicate serial dilutions of DNA were amplified using a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique that reliably detects a single copy of HTLV-I Tax DNA in genomic DNA from 105 cells.23 The viral DNA copy number was calculated from the Poisson distribution of negative samples at the cutoff dilution. HTLV-I viral DNA copy number in PBMCs was determined in 32 asymptomatic carriers attending the HTLV clinic at St Mary's Hospital between 1991 and 2001. Historical HTLV-I proviral loads using the nested PCR were compared with HTLV-I proviral loads determined by real-time PCR on the day of blood donation. Standard 450-mL donations of blood were taken from 5 asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers with varying levels of proviral load at the Clinical Trials Centre, St Mary's Hospital, London, with written donor consent and Ethics Committee approval. Blood was collected into packs containing Pall WBF-2 integral whole blood filters and filtration was performed on day 1 after overnight storage at 4°C. Following filtration, plasma and red cells were separated immediately by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 minutes for Tax and CD3 mRNA quantitation using real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR from samples. PBMCs were obtained from the filter by backwashing with normal saline. DNA from these was extracted and analyzed by nested PCR for Tax.

Quantification of HTLV-I Tax and CD3 mRNA in blood components by real-time PCR

DNA was extracted from 10-mL aliquots of blood components using the QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi kit and RNA was extracted from 1-mL aliquots of blood/buffy coat using the QIAamp RNA blood mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). cDNA synthesis was performed using MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described.24 Real-time PCR and data analysis was performed on the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers and probes were designed to detect HTLV-I Tax DNA and CD3 mRNA using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). Oligonucleotides used for Tax detection were as follows: forward primer 5′-AATAATTCTACCCGAAGACTGTTTGC-3′, reverse primer 5′-CCGTGTTGCCAGGCTGTTA-3′, and TaqMan probe 5′-TTTCCAGCCTGTTAGGGCACCCGT-3′. Primers for CD3 mRNA detection were: forward 5′-GGCAAGATGGTAATGAAGAAATGG-3′, reverse 5′-AGGGCATGTCAATATTACTGTGGTT-3′, and probe 5′-TGGTATTACACAGACACCATATAAAGTCTCCATCTCTGG-3′. For each sample, quantification was measured using the Ct value, defined as the PCR cycle at which a predetermined threshold of signal is exceeded. The identity of the amplified products were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis performed using the Universal M13 forward (−40) primer using the Thermo sequenase kit (Amersham Life Sciences, Amersham, United Kingdom). To create a standard curve for HTLV-I Tax, MT-2 cells were added to whole blood or buffy coat preparations to a final concentration of 2 × 106 cells/L. A 10-fold dilution series was prepared using PBS as the diluent, yielding samples with total leukocyte concentrations of 20 cells/L to 2 × 107cells/L. DNA extracts were prepared from aliquots of each dilution.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel software using a 2-tailed t test. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Removal of MT-2 cells and T lymphocytes by filtration of whole blood and platelets

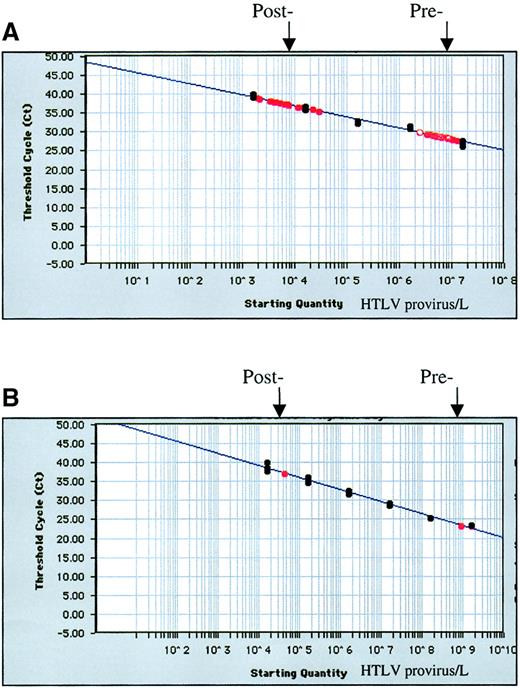

Filtration times for whole blood varied between 6 and 17 minutes with mean values of 10 and 15 minutes on days 0 and 1, respectively. All filtered units met the United Kingdom specification limit of less than 5 × 106 leukocytes/unit (Table1). The standard curve for HTLV Tax quantification was linear over 5 log10 concentration range with a detection limit of 1 HTLV-I copy/mL. HTLV-I Tax was detected in 13 of 16 whole blood units after filtration (Figure1). The removal of T lymphocytes and MT-2 cells from whole blood and platelets during filtration is summarized in Table 1. A comparison of the 2 whole blood filter types and the 2 filtration protocols revealed similar efficacy in the reduction of HTLV-I Tax signal, with no donation giving less than 2.66 log10 removal. Taking both whole blood processing conditions and filter types together, we observed a mean 3.67 log10 reduction in HTLV-I signal, resulting in a residual mean postfiltration provirus load of 3 × 103 HTLV copies/L. There was no correlation between HTLV removal and either filtration time or postfiltration total leukocyte counts.

Reduction in HTLV Tax DNA and CD3 mRNA following leukocyte depletion of 16 whole blood and 8 platelet concentrates spiked with MT-2 cells

| Filter type . | Day of filtration . | HTLV-I log10 reduction (SD) . | CD3 mRNA log10 reduction (SD) . | Residual WBC/μL* flow cytometry (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole blood | ||||

| Pall WBF-2 | 0 | 3.55 (0.41) | 4.48 (0.59) | < 1 |

| Pall WBF-2 | 1 | 3.76 (0.69) | 4.60 (0.57) | < 1 |

| Baxter RZ2000 | 0 | 3.68 (0.68) | 4.87 (0.32) | < 1 |

| Baxter RZ2000 | 1 | 3.67 (0.83) | 4.88 (0.27) | < 1 |

| Mean of whole blood processes | 3.67 (0.60) | 4.71 (0.20) | < 1 | |

| Platelet | ||||

| Pall Autostop | 1 | 2.76 (0.55) | 3.78 (0.18) | 1.37 (0.46) |

| Baxter PLX-5 | 1 | 2.63 (0.68) | 4.15 (0.33) | < 1 |

| Mean of platelet processes | 2.70 (0.58) | 3.97 (0.31) | 1.11 (0.37) |

| Filter type . | Day of filtration . | HTLV-I log10 reduction (SD) . | CD3 mRNA log10 reduction (SD) . | Residual WBC/μL* flow cytometry (SD) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole blood | ||||

| Pall WBF-2 | 0 | 3.55 (0.41) | 4.48 (0.59) | < 1 |

| Pall WBF-2 | 1 | 3.76 (0.69) | 4.60 (0.57) | < 1 |

| Baxter RZ2000 | 0 | 3.68 (0.68) | 4.87 (0.32) | < 1 |

| Baxter RZ2000 | 1 | 3.67 (0.83) | 4.88 (0.27) | < 1 |

| Mean of whole blood processes | 3.67 (0.60) | 4.71 (0.20) | < 1 | |

| Platelet | ||||

| Pall Autostop | 1 | 2.76 (0.55) | 3.78 (0.18) | 1.37 (0.46) |

| Baxter PLX-5 | 1 | 2.63 (0.68) | 4.15 (0.33) | < 1 |

| Mean of platelet processes | 2.70 (0.58) | 3.97 (0.31) | 1.11 (0.37) |

Results are mean (SD) of 4 replicates.

Sensitivity is 1 WBC/μL.

HTLV-I standard curve.

HTLV-I standard curve (black) and prefiltration and postfiltration data (red) on whole blood units (A) spiked with MT-2 cells and filtered on day 1 (n = 8) and (B) and the asymptomatic carrier designated no. 1 in Table 2. Results are expressed as the threshold cycle at which a predetermined signal is exceeded.

HTLV-I standard curve.

HTLV-I standard curve (black) and prefiltration and postfiltration data (red) on whole blood units (A) spiked with MT-2 cells and filtered on day 1 (n = 8) and (B) and the asymptomatic carrier designated no. 1 in Table 2. Results are expressed as the threshold cycle at which a predetermined signal is exceeded.

We quantified HTLV-I Tax in the plasma fraction to assess the contribution of plasma contamination to the overall signal. In 4 samples Tax was undetected in plasma before filtration but was at the borderline of detection after filtration. In the remaining 12 samples the plasma signal either remained constant or decreased following filtration and in all cases was less than 0.25% of that added to whole blood.

For the specific measurement of T lymphocytes, we developed quantitative reverse transcriptase–PCR for subset-specific CD3 mRNA. We have previously shown this to be specific for T cells linear over 5 log10 concentration range, with a sensitivity limit of 30 leukocytes/mL.24 Here we observed a mean 4.71 log10 reduction in CD3 signal after whole blood filtration, indicating that overall T-lymphocyte reduction was around 1 log10 greater than that of MT-2 removal measured by HTLV-I provirus detection.

We also examined removal of MT-2 cells and T lymphocytes (CD3) from 8 platelet concentrates, all meeting the less than 5 × 106leukocytes/unit standard, where we observed a mean 2.76 log10 reduction in HTLV-I Tax with Autostop and 2.63 log10 reduction with PLX-5 (Table 1). The reduction in CD3 signal following platelet filtration was again a mean of 1 log10 greater than Tax, with a mean 3.78 log10reduction for the Pall Autostop filter and 4.15 log10reduction with the Baxter PLX-5.

Filtration of whole blood from HTLV-I asymptomatic carriers

HTLV-I viral load in 32 asymptomatic carriers measured by nested PCR in PBMCs ranged from less than 0.001 to 70 copies of HTLV provirus per 100 PBMCs, with a median viral load of 1.4 copies per 100 PBMCs. Twenty (62.5%) carriers had a viral load greater than 1 per 100 PBMCs. Prefiltration viral load of 5 HTLV-I–infected individuals was also measured by real-time PCR and ranged between 0.01 and 40.6 proviral copies/100 PBMCs (1.0 × 105 to 1.6 × 109proviral copies/L; Table 2). HTLV-I proviral load in the 5 individuals involved in the filtration studies as determined by real-time PCR was 2-fold to 4-fold higher compared to the historical nested PCR but the results were consistently ordered.

Quantification of HTLV-I Tax and CD3 mRNA in whole blood, red cells, and plasma of seropositive asymptomatic carriers before and after leukocyte depletion by filtration

| Donor . | Whole blood before filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Red cells after filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Log10reduction before and after filtration HTLV-I (real-time PCR) . | Log10 reduction before and after filtration CD3 mRNA (real-time PCR) . | Red cells after filtration HTLV-I (nested PCR) . | Plasma prefiltration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Plasma after filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Residual WBC/μL* (flow cytometry) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.61 × 109 | 4.44 × 104 | 4.56 | 3.96 | Not detected | 2.83 × 106 | 2.20 × 105 | 2.20 |

| 2 | 3.26 × 108 | 5.06 × 104 | 3.81 | 4.58 | Positive | 8.60 × 107 | 4.95 × 105 | 3.60 |

| 3 | 2.56 × 108 | Not detected | > 4.0 | 4.12 | Positive | 3.73 × 105 | 1.39 × 105 | < 1 |

| 4 | 2.34 × 107 | Not detected | > 3.2 | Not tested | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | < 1 |

| 5 | 1.01 × 105 | Not detected | > 1 | 4.54 | Not detected | 3.30 × 104 | Not detected | 5.20 |

| Donor . | Whole blood before filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Red cells after filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Log10reduction before and after filtration HTLV-I (real-time PCR) . | Log10 reduction before and after filtration CD3 mRNA (real-time PCR) . | Red cells after filtration HTLV-I (nested PCR) . | Plasma prefiltration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Plasma after filtration HTLV-I copies/L (real-time PCR) . | Residual WBC/μL* (flow cytometry) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.61 × 109 | 4.44 × 104 | 4.56 | 3.96 | Not detected | 2.83 × 106 | 2.20 × 105 | 2.20 |

| 2 | 3.26 × 108 | 5.06 × 104 | 3.81 | 4.58 | Positive | 8.60 × 107 | 4.95 × 105 | 3.60 |

| 3 | 2.56 × 108 | Not detected | > 4.0 | 4.12 | Positive | 3.73 × 105 | 1.39 × 105 | < 1 |

| 4 | 2.34 × 107 | Not detected | > 3.2 | Not tested | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | < 1 |

| 5 | 1.01 × 105 | Not detected | > 1 | 4.54 | Not detected | 3.30 × 104 | Not detected | 5.20 |

Sensitivity is 1 WBC/μL.

Following filtration of blood donations from 5 individuals with a range of viral loads, provirus was detected in 2 of 5 samples by real-time PCR, where we observed a mean HTLV-I proviral reduction of 4.18 log10 and a mean 4.3 log10 reduction in T lymphocytes (Table 2). HTLV-I was detected in the filtered blood of a third donor by nested PCR but not by real-time PCR. These 3 donors had the highest HTLV proviral load (> 6 copies/100 PBMCs by nested PCR). HTLV-I was not detected in the filtered blood of the 2 donors with the lowest proviral load (< 0.35 copies/100 PBMCs). HTLV-I DNA was consistently detected by nested PCR in the cells obtained from the backwashed filters of all donors.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that, following leukocyte depletion according to United Kingdom standard procedures, HTLV-I proviral DNA remained detectable in 13 of 16 whole blood samples, 8 of 8 filtered platelets spiked with MT-2 cells, and in blood from 3 of 5 asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers. This corresponded to 3.5 log10 to 4.5 log10 reduction for whole blood, 2 log10 to 3 log10 reduction for platelets, and a mean 4.18 log10 reduction of provirus after filtration of whole blood from asymptomatic carriers. Postfiltration provirus was detected in the 3 carriers with prefiltration provirus loads of greater than 108 copies/L. This level of viremia, equivalent to 5 HTLV-I copies/100 PBMCs, was exceeded in approximately 30% of asymptomatic carriers tested. Firm conclusions on a threshold load in HTLV carriers which would exceed current filtration capacity cannot yet be drawn due to the small number of individuals tested, but these data are suggestive that a threshold value exists. Blood donations are not screened for anti–HTLV-I in most developed countries except North America, Japan, Australia, France, Portugal, and in targeted donations in the Netherlands and Sweden. In those countries that do not screen for antibody, should they all filter whole blood within 2 days of collection at blood centers, as done in the United Kingdom, the majority of infectious donations would no longer be infectious. However, this depends on the proviral load in the donor population. Our findings suggest that, assuming the range of viremia in symptomatic carriers is broadly consistent between countries, a policy of relying on universal leukocyte depletion (LD) alone would allow up to 30% of potentially HTLV infectious donations to enter the blood supply. The transmission rate from donations in which the HTLV load has been reduced by LD is not known, but considering that previous look-back studies from non-LD blood have reported transmission rates of 13% to 28%,9-11 it is unlikely that complete protection of transfusion recipients can be guaranteed by LD alone. In addition, individuals with high viral loads may donate many times over a number of years, potentially placing larger numbers of recipients at risk. In countries screening for HTLV-I antibodies, filtration is very likely to eliminate the infectious risk from “window period” donors undetected serologically. No data on viral load in preseroconversion samples are available, but the viral load was very low in the early phase of infection in an individual where the date of exposure was known, only 0.014 copies/100 PBMC's, rising over 24 months to 1.12%.25

In a previous study of HTLV-I removal using an earlier generation of filters and semiquantitative detection, removal of infected cells from HTLV-I carriers was 1 log10 to 3 log10 while at least 3 log10 reduction was observed for cultured cells.26 A low viral input load in the HTLV-I–infected donors accounted for these differences. However, in our study, viral load in asymptomatic carriers was not a limitation, since the prefiltration Tax HTLV-I signal in 4 of 5 donors was equal to or greater than that of MT-2–spiked units.

It was unexpected to detect HTLV-I genome in the plasma of both MT-2–spiked normal blood and blood from asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers since plasma components have never been shown to transmit HTLV. The data in Table 2 suggest that during sample preparation, cell breakage is sufficient to release cellular DNA in quantities detectable with real-time PCR. The 1 to 3 log10 difference between whole blood and plasma concentration suggests that 0.1% to 10% of HTLV-I provirus can be so released. It is possible that HTLV-I–infected T cells might be particularly fragile. This hypothesis is indirectly supported by the fact that preparation of MT-2 cells for spiking required the presence of 20% human AB serum in the washing buffer to limit a substantial loss of HTLV-I Tax during the procedure.

We studied T-lymphocyte removal by the measurement of subset-specific CD3 mRNA. In line with our previous study of random blood donors,24 we found that CD3 signal reduction in asymptomatic carriers was similar to that of Tax, suggesting that removal of HTLV-I–infected T lymphocytes by the filter was equivalent to that of overall T-lymphocyte removal. By contrast, in the MT-2 model system, provirus removal was approximately 1 log10 lower than removal of T lymphocytes as measured by CD3 mRNA. This difference may relate to differences in expression of cell-surface molecules relevant to filtration in HTLV-I–cultured cell lines such as MT-2.27 In vitro studies have shown that mononuclear cells of patients with HAM showed decreased expression of L-selectin (CD62L) and increased very late activation antigen 4 (VLA-4) (CD49d) levels relative to HTLV carriers and controls.28 In addition, removal of T lymphocytes may vary according to the percentage of total T cells carrying the provirus, which ranges between 0.1% and 0.3% in the MT-2 “spiking” model and from 0.005% to 100% in the asymptomatic carriers in this study. Therefore removal of MT-2 cells by filtration may be representative of T-lymphocyte leukocyte depletion of asymptomatic carrier donations only over a narrow part of the range of provirus loads. After filtration, MT-2–spiked whole blood contained a mean 3 × 103 HTLV-I proviral copies/L that are detectable in 13 of 16 filtered units, while the 2 filtered clinical units with detectable HTLV-I contained 4 × 104 to 5 × 104 copies/L, corresponding to less than 3 × 104 remaining infected T cells/unit. Greater postfiltration residual provirus in these asymptomatic carriers reflects the higher prefiltration provirus load of 3.26 × 108 to 1.61 × 109/L compared to 2 × 106/L in the MT-2 model.

The critical question is the potential of leukocyte depletion to protect against HTLV-I transmission and whether or not 3 log10 to 4 log10 HTLV removal is sufficient to prevent transmission. This clearly depends on the infectious dose, which is unknown in humans. The smallest reported transfusion volume resulting in HTLV-I transmission is 44 mL but the viral load of the donor was not reported.29 Although the related virus HTLV-II is common in drug users sharing needles, HTLV-I is also transmitted through this route30 and thus, innocula of less than 1 mL of blood (a typical volume through needle sharing among intravenous drug users) are enough to transmit. HTLV-I can also be transmitted to rabbits by as few as 4 × 104 infected lymphocytes,31 again suggesting that preventing HTLV transmission using leukocyte depletion alone may be difficult or impossible.

These results indicate that leukocyte depletion alone, in the absence of screening or universal pathogen inactivation, may not guarantee protection from HTLV transmission. Although no cases of HTLV transmission by transfusion have been reported to the United Kingdom hemovigilance scheme between 1996 and 2000,32 rapid disease development is extremely rare and such cases may remain asymptomatic escaping detection.

The authors would like to thank Dr Jill Walton and staff of the apheresis clinic for blood components and Dr Charlotte Llewelyn for statistical advice.

Supported by Pall Biomedical.

L.M.W. has an ongoing research contract with Pall Biomedical.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Lorna M. Williamson, Division of Transfusion Medicine, NBS East Anglia, Long Road, Cambridge, CB2 2PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: lorna.williamson@nbs.nhs.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal