Abstract

Adoptive immunotherapy using in vitro–generated donor-derived cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) can be effective in the treatment of relapsed leukemia after allogeneic transplantation. To determine effector cell characteristics that result in optimal in vivo antileukemic efficacy, we developed an animal model for human CTL therapy. Nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/scid) mice were inoculated with either of 2 primary human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), denoted as SK and OF. Anti-SK and anti-OF CTLs were generated in vitro by repeated stimulation of donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells with either SK or OF cells. Both CTL lines displayed HLA-restricted reactivity against the original targets and non-major histocompatibility class (MHC)–restricted cross-reactivity in vitro. The CTLs were administered intravenously weekly for 3 consecutive weeks to mice engrafted with either SK or OF leukemia. In 3 of 8 SK-engrafted and anti-SK–treated mice, complete remissions were achieved in blood, spleen, and bone marrow. In the remaining 5 animals partial remissions were observed. In 4 of 4 OF-engrafted anti-OF–treated mice partial remissions were observed. The antileukemic effect of specific CTLs was exerted immediately after administration and correlated with the degree of HLA disparity of the donor-patient combination. In cross-combination–treated animals, no effect on leukemic progression was observed indicating that in vivo antileukemic reactivity is mediated by MHC-restricted effector cells. The CTLs, however, displayed an impaired in vivo proliferative capacity. Ex vivo analysis showed decreased reactivity as compared to the moment of infusion. We therefore conclude that the model can be used to explore the requirements for optimal in vivo efficacy of in vitro– generated CTLs.

Introduction

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) has been successfully used in the treatment of hematopoietic malignancies.1 The therapeutic benefit of allogeneic SCT is not merely to provide hematopoietic rescue after cytoreductive treatment. Donor-derived T cells administered during or after the transplantation contribute to achieving and maintaining remission after SCT.2,3 Treatment of patients in relapse after transplantation with donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) has demonstrated the curative potential of this graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. DLI resulted in approximately 80% remissions in relapsed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).4 In acute leukemia response rates were lower, but remissions of up to 40% of the cases have been reported.5

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is frequently observed as a complication of DLI. Although the occurrence of GVHD is correlated with an antileukemic response,5 GVHD and GVL appear to be separable because complete remissions have been observed in the absence of clinically significant GVHD.6 One possibility of reducing GVHD reactivity in favor of GVL reactivity may be the application of in vitro–selected cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) with relative specificity for leukemic cells. It has been shown that donor-derived CTLs reactive with leukemic cells from the patient can be generated from HLA-identical donor-recipient combinations by repeated stimulation of donor-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs ) with leukemic cells.7,8 Previously, we have shown that infusion of these in vitro–generated and expanded CTLs can induce complete remissions in some patients with refractory leukemia after allogeneic SCT.9 However, in only 2 of 6 evaluable patients treated with in vitro–selected and expanded CTLs were complete remissions obtained (J.H.F.F., unpublished data, November 2001). Little is known about the kinetics of CTL therapy on malignancies in humans. The relatively small numbers of patients treated and the complexity involved in identifying and following the CTLs within the background of the patients' leukocytes are major obstacles in studying the kinetics of CTL therapy. A preclinical model in which the fate of human CTLs and their effect on human leukemia can be studied in detail is therefore needed.

The immunodeficient (scid) or nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/scid) mouse has been demonstrated to be a representative host for human malignant and normal hematopoietic cells.10 The model has also proven to be suitable for the study of human effector cells. Minor histocompatibility antigen (mHAg)–specific CTLs were demonstrated to eradicate leukemic progenitor cells when cocultured directly before infusion into scid mice, preventing leukemic engraftment and outgrowth in these mice.11 In another report, the efficacy and specificity of in vitro–generated Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–specific CTLs was demonstrated in scid mice engrafted subcutaneously or intraperitoneally with human EBV-transformed B cells, illustrated by significant prolongation of survival.12However, multiple aspects of adoptive immunotherapy remain unclear despite these studies. Correlations between target and effector cell types or properties and in vivo efficacy can be identified most optimally when their in vivo behavior can be monitored sequentially in individual animals.

In this report, we present the establishment of a small animal model of human antileukemic CTL therapy. As a model of human leukemia, immunodeficient NOD/scid mice were engrafted with human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) as previously described.13 In this model, primary leukemic cells from patients with ALL are engrafted into NOD/scid mice and leukemic progression is monitored within each individual animal. The progression of leukemia has been demonstrated to be of an exponential nature with a constant rate, that is, a constant population doubling time, during disease progression. Because of this, leukemic progression is highly predictable from early stages of engraftment within individual animals. Therefore, this leukemia model in which the kinetics of leukemia progression can be studied in detail was used to apply immunotherapy using human allogeneic CTLs. For this, human alloreactive CTLs were generated in vitro and administered to the leukemic NOD/scid mice; follow-up was performed by sequential analysis of peripheral blood samples. In crossover experiments using 2 donor-patient combinations, we demonstrated antileukemic reactivity of the CTLs with a specificity similar to the established in vitro specificity. Monitoring of leukemic cell load during CTL therapy revealed differences in kinetics and efficacy of antileukemic CTL reactivity in vivo for both combinations. We conclude that the kinetic NOD/scid mouse model can be used for developing improved strategies for in vitro generation and in vivo application of CTL.

Materials and methods

Patient and donor material

Leukemic cells were obtained by leukapheresis from 2 patients with ALL, denoted SK and OF. Normal peripheral blood was collected from an unrelated healthy donor. PBMC fractions were obtained by isolation on a Ficoll density gradient. Leukemic cell suspensions contained more than 85% leukemic blasts and were cryopreserved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in liquid nitrogen. As described previously,13SK cells were classified as pro-B ALL cells and were CD10−, CD19+, and CD20−. OF cells were characterized as CML lymphoid blast crisis CML cells expressing CD10, CD19, and CD20. Both leukemias expressed HLA class I and II. The HLA type of the patients and the donor are shown in Table 1. Approval was obtained from the Leiden University Medical Center review board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

HLA type of donor and patients

| HLA class I | ||||||

| Donor | A2 | A24 | B7 | B62 | Cw9 | Cw7 |

| SK | A1* | A3* | B18* | B35* | Cw4* | Cw7 |

| OF | A2 | B60* | Cw10* | |||

| HLA class II | ||||||

| Donor | DR1 | DR13 | DQ5 | DQ6 | ||

| SK | DR10* | DR12* | DQ5 | |||

| OF | DR13 | DQ6 |

| HLA class I | ||||||

| Donor | A2 | A24 | B7 | B62 | Cw9 | Cw7 |

| SK | A1* | A3* | B18* | B35* | Cw4* | Cw7 |

| OF | A2 | B60* | Cw10* | |||

| HLA class II | ||||||

| Donor | DR1 | DR13 | DQ5 | DQ6 | ||

| SK | DR10* | DR12* | DQ5 | |||

| OF | DR13 | DQ6 |

Donor-patient disparate alleles.

NOD/scid mice

Female NOD/scid mice aged 5 to 6 weeks were obtained from Bomholtgaard Breeding and Research Center (Ry, Denmark), and were housed in sterile filter-top cages placed in a laminar backflow cabinet. Mice were supplied with sterile food and acidified sterile water containing 70 mg/L polymixin B and 80 mg/L ciprofloxacin. No conditioning regimens were used prior to inoculation of leukemic cells. Directly before inoculation into NOD/scid mice the leukemic cells were thawed in the presence of DNAse (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) and washed twice in RPMI (Biowhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biowhittaker). Cell viability was ensured to be more than 95% by eosin dye exclusion. Leukemic cells (107) were injected intravenously in a lateral tail vein in 200 μL RPMI with 10% FCS (RPMI/FCS).

CTL culture and characterization

The CTL lines were generated by culturing freshly thawed PBMCs (2 × 105/mL) with irradiated (25 Gy) leukemic cells from patients SK or OF (4 × 105/mL). CTL culture medium consisted of Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Biowhittaker) supplemented with 10% pooled prescreened human serum (IMDM/HS). After 5 days, 100 IU/mL recombinant human interleukin 2 (IL-2; Chiron, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was added. Weekly, CTLs were stimulated with 2-fold numbers of irradiated (25 Gy) leukemic cells.

Immunophenotypical characterization of CTLs was performed using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antibodies against human CD3, CD8, T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ, TCRγδ, and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies against human CD4, CD25, and CD56 (all Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) directly before administrations to the mice.

The contributions of different cytotoxic components to the total reactivity of the CTL lines against SK or OF cells were quantified in a standard 51Cr release assay.7 To determine HLA class I– or class II–restricted cytotoxicity of the CTL lines, blocking experiments were conducted using HLA class I blocking antibody W6/3214 and class II blocking antibody 7.5.10.115 (both courtesy of Dr Arend Mulder, Department of Immunohematology and Blood Bank, Leiden, The Netherlands). In these experiments target cells were preincubated with saturating concentrations of antibodies. To block the non-HLA–restricted cytotoxic component, cold target inhibition using K562 cells was performed in some experiments. K562 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS (Biowhittaker). In the cold target inhibition assay, K562 cells were added to the plated radiolabeled target cells before addition of the effector cells at K562 to leukemia cell ratios ranging from 50 to 0.2 in serial 2-fold dilutions.

Adoptive immunotherapy

After inoculation with leukemic cells, engraftment of leukemia was monitored in peripheral blood of individually marked NOD/scid mice as described previously.13 When leukemic cells were observed in peripheral blood the animals were ranked on the basis of their leukemic cell counts (LCCs) and cohorts of 3 consecutive mice were formed. Because the rate of leukemic progression has been shown to differ between individual mice and this variation could be mistaken for treatment effect, mice within these cohorts were again grouped on the basis of their leukemic engraftment levels. Of each group, the animal with the highest LCC received CTLs specific for the engrafted leukemia (eg, SK-reactive CTLs in the case of SK-engrafted mice). The animal with second highest LCC received the cross-combination CTL (eg, OF-reactive CTLs in the case of SK-engrafted mice). The animal with lowest LCC was used as a control animal. Eight SK-engrafted cohorts and 4 OF-engrafted cohorts were used in total.

Administration of CTLs was repeated 3 times with a 7-day interval. CTLs were administered intravenously in a lateral tail vein in RPMI/FCS at a dose of 20 to 40 × 106 CTLs per mouse per administration, resulting in a cumulative dose of 100 × 106 for each mouse. In all administrations, the dose of specific CTLs equalled the dose of cross-combination CTLs. Control-treated animals received RPMI/FCS only. Directly before CTL treatment, and on days 1 to 4 following CTL or control injection, all mice received 2 × 104 IU IL-2 intraperitoneally.

During the treatment period, peripheral blood samples were taken regularly and analyzed for leukemic cells and CTLs as described below. Two to 4 days after the last CTL administration, the mice were killed, and spleen and bone marrow cell suspensions were prepared by straining the spleen through a 100-μm Falcon cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and flushing both femurs with RPMI/FCS. The cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry. To culture CTLs ex vivo, the cell suspensions were cultured in IMDM/HS in the presence of 100 IU IL-2/mL without stimulator cells for 1 week. Then the cell suspensions were restimulated weekly with their specific stimulator cells (ie, irradiated SK cells for suspensions recovered from anti-SK–treated mice or irradiated OF cells for suspensions recovered from anti-OF–treated mice) in the presence of 100 IU IL-2/mL.

Monitoring of leukemic progression during therapy

To monitor leukemic progression during therapy, absolute LCCs in peripheral blood were determined as described previously.13 In short, 50-μL peripheral blood samples were frequently taken from a lateral tail vein using capillary blood collection tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). For flow cytometric analysis, blood samples were subjected to red blood cell lysis using NH4Cl, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1% human serum albumin. These peripheral blood samples, as well as the spleen cell suspensions and bone marrow suspensions that were prepared at experimental end points, were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer. Nucleated cells were identified on the basis of their forward and sideward light scattering properties. In all samples murine leukocytes were stained using PE-conjugated anti-murine CD45 (Ly5; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). The percentages of leukemic cells in the nucleated cell population were determined by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD19 for SK leukemia and FITC-conjugated anti-human CD20 monoclonal antibodies for OF, respectively (both Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). LCCs were calculated as LCC = NCC × percentage leukemic cells where NCC is the nucleated cell count. Likewise, the percentage of CD3+ cells was determined by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD3 antibodies (Becton Dickinson) and CD3+ cell counts were calculated as NCC × percentage CD3+cells.

Data analysis

Because of differences in the rate of leukemic progression between the cohorts of mice, the data were normalized. In each group of mice, LCCs in the control-treated animal at the experimental end point were set at 100%, and all LCCs within a group were expressed as a percentage of these controls. The effect of treatment was analyzed for statistical significance using mixed-model ANOVA. Intertreatment differences in leukemic cell content of spleen and bone marrow cell suspensions at experimental end point were tested for significance by performing a 2-tailed Student t test.

If no leukemic cells could be detected in peripheral blood, bone marrow, or spleen of CTL-treated mice, the leukemic status was considered as complete remission. If leukemic cells could be detected at levels of less than 10% of those in control-treated mice, leukemic status was considered a partial remission.

Results

Alloreactive CTL lines

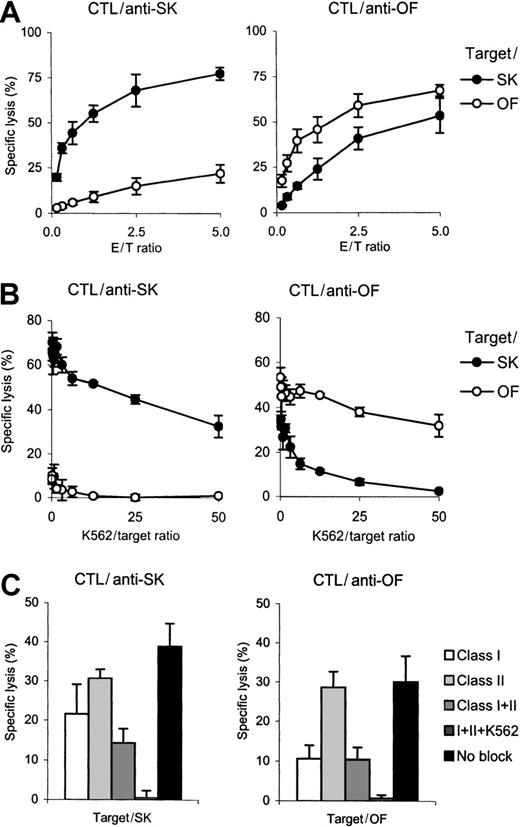

Anti-SK and anti-OF CTL lines showed similar immune phenotype as shown in Table 2. In a 51Cr release assay anti-SK and anti-OF CTLs displayed high cytotoxicity to their specific targets. Anti-SK CTLs displayed only low reactivity to OF cells, but anti-OF CTLs showed significant cross-reactivity against SK cells (Figure 1A). Because SK and OF cells did not share HLA alleles that were antigenic to the donor (Table1), this cytotoxicity was hypothesized to be non-MHC–restricted natural killer (NK) activity. To block this possible non-MHC–restricted component, a cold target inhibition assay was performed using K562 cells. Addition of a 50-fold excess of K562 cells completely blocked lysis of the cross-combinations illustrating that the cross-combination cytotoxicity was indeed non-MHC restricted (Figure 1B).

Mean immune phenotype of infused CTL lines

| . | Percentage of cells staining ± SD . | |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-SK . | Anti-OF . | |

| CD3+ | 78 ± 11 | 87 ± 12 |

| CD3+CD4+ | 45 ± 10 | 58 ± 12 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 28 ± 3 | 24 ± 4 |

| CD3+CD25+ | 60 ± 14 | 73 ± 15 |

| CD3−CD56+ | 19 ± 10 | 11 ± 9 |

| TCRαβ+ | 65 ± 14 | 78 ± 12 |

| TCRγδ+ | 12 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 |

| . | Percentage of cells staining ± SD . | |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-SK . | Anti-OF . | |

| CD3+ | 78 ± 11 | 87 ± 12 |

| CD3+CD4+ | 45 ± 10 | 58 ± 12 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 28 ± 3 | 24 ± 4 |

| CD3+CD25+ | 60 ± 14 | 73 ± 15 |

| CD3−CD56+ | 19 ± 10 | 11 ± 9 |

| TCRαβ+ | 65 ± 14 | 78 ± 12 |

| TCRγδ+ | 12 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 |

Cytotoxicity and specificity of anti-SK and anti-OF CTL lines.

(A) The cytotoxicity of both CTL lines was tested in a 4-hour51Cr release assay against primary SK or OF cells at several effector-to-target ratios. (B) Inhibition of LAK or NK activity (or both) of the CTL lines by cold target inhibition using K562 cells. Increasing numbers of unlabeled K562 cells were added to51Cr-labeled SK or OF target cells at an effector-to-hot target ratio of 2:1. (C) HLA restriction of cytotoxicity. HLA class I or HLA class II was blocked on the target cells using monoclonal antibodies in the presence or absence of a 50-fold excess of K562 cells. Cytotoxicity was performed at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2.

Cytotoxicity and specificity of anti-SK and anti-OF CTL lines.

(A) The cytotoxicity of both CTL lines was tested in a 4-hour51Cr release assay against primary SK or OF cells at several effector-to-target ratios. (B) Inhibition of LAK or NK activity (or both) of the CTL lines by cold target inhibition using K562 cells. Increasing numbers of unlabeled K562 cells were added to51Cr-labeled SK or OF target cells at an effector-to-hot target ratio of 2:1. (C) HLA restriction of cytotoxicity. HLA class I or HLA class II was blocked on the target cells using monoclonal antibodies in the presence or absence of a 50-fold excess of K562 cells. Cytotoxicity was performed at an effector-to-target ratio of 1:2.

To determine the HLA class I– or II–restricted component of the overall cytotoxicity, both CTL lines were tested for cytotoxicity against SK or OF cells that were pretreated with HLA class I or HLA class II blocking antibodies (Figure 1C). As expected from the HLA disparities shown in Table 1, recognition of SK cells by anti-SK CTLs was both HLA class I and class II restricted, whereas recognition of OF cells by anti-OF CTL was HLA class I restricted only. Cytotoxicity was completely blocked when anti-HLA class I and anti-HLA class II monoclonal antibodies and a 50-fold excess of K562 cells were added simultaneously.

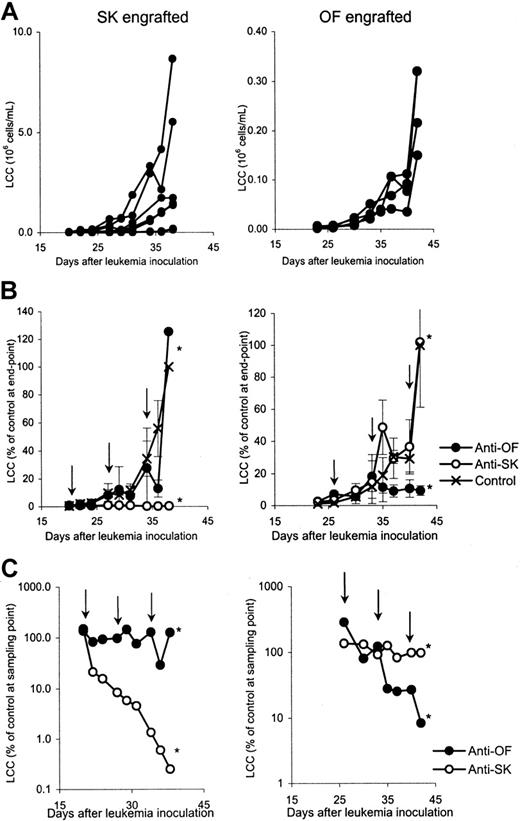

Monitoring of leukemic status during CTL therapy

Cohorts of mice were engrafted with human ALL and monitored for engraftment by sampling of peripheral blood. When leukemic cells could be detected, CTL therapy was started. The absolute LCCs at the start of treatment ranged from 3 × 103 to 36 × 103cells/mL in SK-engrafted animals and 11 × 103 to 22 × 103 cells/mL in OF-engrafted animals. On treatment, the LCCs in the control animals receiving IL-2 only continued to increase exponentially in both SK- and OF-engrafted cohorts (Figure2A). The absolute LCCs at the experimental end point ranged from 1.8 × 105 to 8.6 × 106/mL in the 8 SK-engrafted control animals and 1.5 to 3.2 × 105/mL in the 4 OF-engrafted control animals. In SK-engrafted mice the administration of anti-SK CTLs resulted in a complete remission in 3 of 8 treated animals (Figure 2B). In all remaining animals a partial remission was achieved at the experimental end point with LCCs that were reduced by 98.0% to 99.8% as compared to control-treated animals. In 4 of 4 OF-engrafted, anti-OF treated animals, a partial remission was achieved, with leukemic cell counts reduced by 90% to 95% as compared to LCCs of control mice. In SK- or OF-engrafted animals that were treated with the cross-combination CTLs no remissions were obtained.

In vivo antileukemic effect of CTLs monitored in peripheral blood.

Mice were inoculated with SK (left panels) or OF (right panels) leukemia cells, and absolute LCCs in peripheral blood were determined. When leukemic cells were observed, 3 doses of anti-SK CTLs, anti-OF CTLs, or control injections were administered with a 7-day interval (time points indicated by arrows). (A) Absolute LCCs in control-treated animals during the treatment period. (B) LCCs expressed as percentage of counts in control animals at experimental end point. (C) LCCs expressed as percentage of counts in control animals at time of sampling. Each line represents the mean of 4 to 8 mice. The asterisk represents statistically significant differences (P ≤ .05).

In vivo antileukemic effect of CTLs monitored in peripheral blood.

Mice were inoculated with SK (left panels) or OF (right panels) leukemia cells, and absolute LCCs in peripheral blood were determined. When leukemic cells were observed, 3 doses of anti-SK CTLs, anti-OF CTLs, or control injections were administered with a 7-day interval (time points indicated by arrows). (A) Absolute LCCs in control-treated animals during the treatment period. (B) LCCs expressed as percentage of counts in control animals at experimental end point. (C) LCCs expressed as percentage of counts in control animals at time of sampling. Each line represents the mean of 4 to 8 mice. The asterisk represents statistically significant differences (P ≤ .05).

To illustrate the kinetics of the in vivo antileukemic effect of CTLs, the data were expressed as the percentage of controls at each individual sampling point (Figure 2C). In SK-engrafted mice the LCCs rapidly decreased after the first administration of anti-SK CTLs. The antileukemic effect of anti-OF CTLs in OF-engrafted mice showed slower kinetics.

At the experimental end point, the animals were killed and bone marrow and spleen cell suspensions were analyzed for their leukemic content (Figure 3). Engraftment levels in the organs of cross-treated mice did not differ significantly from those in control animals. The complete hematologic remissions that were observed in SK-engrafted anti-SK–treated animals were confirmed in the bone marrow and spleens, whereas in 4 of 5 animals with partial remissions in peripheral blood, the partial remission state was confirmed. One SK-engrafted animal with a partial remission in peripheral blood showed leukemic engraftment levels in the bone marrow of 70% of control animals.

Leukemic content in bone marrow and spleens.

End-point determinations of leukemic levels in bone marrow and spleens are shown for mice engrafted with SK leukemia (left) or OF leukemia (right) treated with anti-SK or anti-OF CTLs or control injections. Engraftment levels are expressed as the percentage leukemic cells of all nucleated cells in the bone marrow or spleen cell suspensions. Each bar represents the mean of 4 to 8 mice. The asterisk represents statistically significant differences (P ≤ .05).

Leukemic content in bone marrow and spleens.

End-point determinations of leukemic levels in bone marrow and spleens are shown for mice engrafted with SK leukemia (left) or OF leukemia (right) treated with anti-SK or anti-OF CTLs or control injections. Engraftment levels are expressed as the percentage leukemic cells of all nucleated cells in the bone marrow or spleen cell suspensions. Each bar represents the mean of 4 to 8 mice. The asterisk represents statistically significant differences (P ≤ .05).

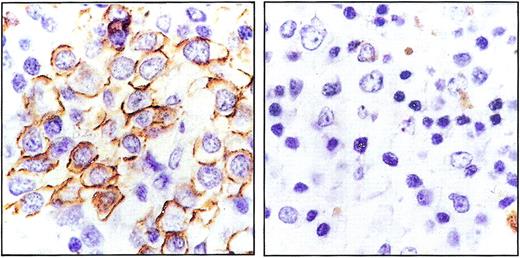

In OF-engrafted anti-OF–treated animals, organ analysis revealed achievement of partial remissions in both spleen and bone marrow. Immunostained spleen sections of OF-engrafted mice treated with anti-OF or anti-SK CTLs are shown in Figure 4.

Partial remissions in bone marrow and spleen.

Spleen sections of OF-engrafted mice treated with anti-SK CTLs (left) or anti-OF CTLs (right). Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and immunostained with peroxidase-linked antihuman CD20. Original magnification × 600.

Partial remissions in bone marrow and spleen.

Spleen sections of OF-engrafted mice treated with anti-SK CTLs (left) or anti-OF CTLs (right). Sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and immunostained with peroxidase-linked antihuman CD20. Original magnification × 600.

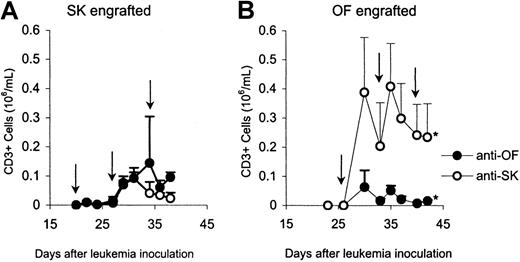

Monitoring of effector cells during CTL therapy

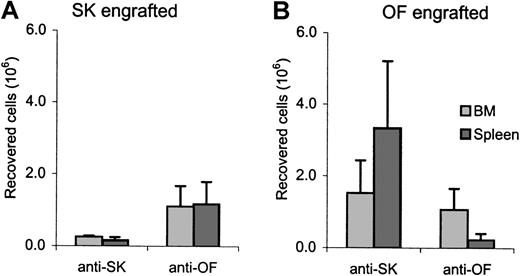

Blood samples were also analyzed for the presence of the infused CTLs. In mice that received IL-2 alone no CD3+ cells were detected at any time. In the peripheral blood of all mice that received CTL treatment, CD3+ cells could be observed after the first CTL administration (Figure 5). In SK-engrafted as well as in OF-engrafted mice, higher numbers of CD3+ cells were observed in the animals that had been treated with the cross-combination CTLs than in mice that were treated with the specific CTLs, although a significant difference was only observed in the OF-engrafted mice. At the experimental end point, effector cells were also observed in bone marrow and spleen (Figure6). All recovered cells expressed CD3 and TCRαβ. As observed in peripheral blood, significantly higher numbers of CD3+ cells were found in the organs of the animals treated with cross-combination CTLs than in the animals treated with the specific CTLs.

Monitoring of effector cells.

CD3+ cell counts in peripheral blood of SK-engrafted (left) and OF-engrafted (right) mice treated with anti-SK or anti-OF CTLs. The time points of CTL administration are indicated by arrows. The asterisk represents a statistically significant difference (P ≤ .05).

Monitoring of effector cells.

CD3+ cell counts in peripheral blood of SK-engrafted (left) and OF-engrafted (right) mice treated with anti-SK or anti-OF CTLs. The time points of CTL administration are indicated by arrows. The asterisk represents a statistically significant difference (P ≤ .05).

Recovery of CD3+ cells in bone marrow and spleen.

Total numbers of recovered CD3+ cells at experimental end point in bone marrow and spleen of CTL-treated SK-engrafted (left) and OF-engrafted (right) mice. Total CD3+ cell numbers in the bone marrow compartment were calculated from the numbers recovered from 2 femurs.

Recovery of CD3+ cells in bone marrow and spleen.

Total numbers of recovered CD3+ cells at experimental end point in bone marrow and spleen of CTL-treated SK-engrafted (left) and OF-engrafted (right) mice. Total CD3+ cell numbers in the bone marrow compartment were calculated from the numbers recovered from 2 femurs.

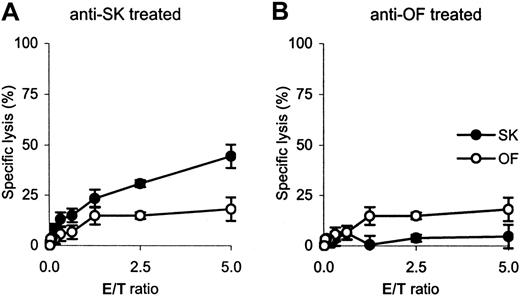

To further characterize the CD3+ cells that were recovered at the experimental end point, the cell populations from 2 experiments with SK-engrafted mice and from a single experiment with OF-engrafted mice were further cultured in vitro. Expansion of the CTLs using their specific stimulator cells was observed only for CD3+ cells recovered from the anti-OF– and anti-SK–treated OF-engrafted mice. The cytotoxicity of the ex vivo–expanded CTLs was tested in a standard 51Cr release assay after the first stimulation and demonstrated to be diminished as compared to the cytotoxicity of the infused CTL lines (Figure 7). No further expansion was observed after a second stimulation with leukemic cells.

Cytotoxicity of ex vivo–expanded CTLs.

Analysis is shown for anti-SK and anti-OF CTLs recovered from OF-engrafted mice as determined in a standard 51Cr-release assay. The recovered CTLs display diminished cytotoxicity as compared to Figure 1A.

Cytotoxicity of ex vivo–expanded CTLs.

Analysis is shown for anti-SK and anti-OF CTLs recovered from OF-engrafted mice as determined in a standard 51Cr-release assay. The recovered CTLs display diminished cytotoxicity as compared to Figure 1A.

Discussion

In this study, we present an animal model for human adoptive cellular immunotherapy using in vitro–generated and –expanded CTLs. Administration of the in vitro–generated and –expanded CTLs to NOD/scid mice engrafted with human ALL cells resulted in complete and partial remissions in contrast to animals receiving control treatment, and the in vivo antileukemic effect of the CTLs was exerted with the MHC-restricted specificity that was generated in vitro.

The NOD/scid mouse model offers several opportunities for studying the effects and kinetics of human CTL therapy. Human cells, both leukemia and effector cells, can be easily identified from the NOD/scid mouse background using standard flow cytometric techniques. More importantly, there are no restrictions on the HLA type of the leukemic cells or the donors that are used in the NOD/scid mouse because of its murine and immunodeficient nature. As demonstrated in this study, cellular immunotherapy of human leukemia can be studied in an allogeneic setting because neither of the 2 cell populations needs to be syngeneic with the host.

Some studies on the efficacy of human CTLs to eradicate human malignant hematopoietic cells before or after engraftment into immunodeficient mice have already been described. It has been demonstrated that in vitro–generated mHAg-specific cytotoxic effector cells can prevent engraftment of acute myeloid leukemia, when incubated with the malignant cells before inoculation into NOD/scid mice.11In vitro EBV-specific CTLs significantly prolonged survival in mice engrafted with EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid B-cell lines.12 Moreover, these EBV-specific CTLs were shown to specifically home to autologous and not HLA-mismatched tumors and cause tumor regression. Another study reported antileukemic efficacy of in vitro–generated autologous cytokine-induced killer cells in scid mice engrafted with human CML cells.16 Although these reports clearly demonstrate the feasibility of studying human effector cell efficacy in the scid mouse in vivo environment, a more refined model that covers the events between inoculation of effector cells and clinical response is needed. Such a model could be used to clarify the kinetic aspects of CTL therapy and to determine effector cell population qualities that result in optimal in vivo antileukemic efficacy.

In this study, during the experimental period 3 consecutive doses of CTLs were administered and LCCs in the treated mice dropped at a constant rate in comparison to control-treated mice. These results indicate that the in vivo effect of the infused CTLs was instantaneous and CTLs exerted their effect directly on administration. The degree of HLA disparity between patient and donor correlated with the in vivo antileukemic reactivity. Anti-SK CTLs exerted superior specific antileukemic efficacy as compared to anti-OF CTLs in vivo because during the treatment period LCCs decreased by 3 logs in SK-engrafted mice treated with anti-SK CTLs against 2 logs in OF-engrafted mice treated with anti-OF CTLs. Furthermore, in the first group complete remissions were obtained, whereas in the second group only partial remissions were observed. In vitro cytotoxicity analysis revealed that anti-SK CTL reactivity was both HLA class I and II restricted, whereas anti-OF CTL reactivity was HLA class I restricted only. These results suggest that HLA class II–restricted T cells may be needed for an optimal efficacy of adoptively transferred CTLs as reported elsewhere in humans17 as well as in CD4-deficient mice18receiving adoptive immunotherapy for viral infections.

Of the cumulative dose of 100 × 106 CTLs that was administered to the mice during the experimental period, only a fraction could be recovered at the experimental end point. Remarkably, more CTLs could be recovered from animals that were treated with CTLs that were not specific for the leukemia engrafted in the animals. Although the in vitro–generated CTLs were capable of homing to engrafted leukemic cells and subsequently of specific recognition and cytotoxicity, their proliferative capacity after administration appeared to be compromised. Similar observations have been made previously in scid mice engrafted with either human CTL clones or lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells.19 In vivo, this may be in part the result of activation-induced cell death or induction of anergy. This may be due to a discrepancy between the in vitro culture conditions and the conditions in the living host. Although the mice were given IL-2 daily for 5 days after each CTL administration, serum levels may have differed from the in vitro IL-2 levels resulting in activation-induced cell death through cytokine deprivation.20 The model offers an opportunity to investigate whether adaptations in the culturing conditions, such as changes of IL-2 concentration or application of different cytokines in vitro, may result in a prolonged in vivo lifespan and improved in vivo survival and expansion of the cultured CTLs.

As reported previously, we demonstrated the generation and clinical application of leukemia reactive CTLs by repeated stimulation of donor with leukemic cells from the HLA-identical patient.9 In contrast to in vitro–generated and –expanded EBV or cytomegalovirus epitope–specific CTLs,17 21 leukemia reactive CTLs may be very heterogenous with respect to epitope specificity and effector cell type. It has been suggested that non-MHC–restricted effector cells may contribute significantly to the antileukemic effect after transplantation. In this study, 2 alloreactive CTL lines with MHC-restricted specificity for leukemic cells from either of 2 patients were generated. The CTL lines consisted predominantly of CD3+TCRαβ+ cells, but considerable amounts of CD3−CD56+ NK cells and CD3+TCRγδ+ cells were generated, and both lines were demonstrated to contain an MHC-nonrestricted cytotoxic component. It is likely that this MHC-nonrestricted cytotoxicity was exerted by CD3−CD56+ NK cells because it could be entirely inhibited by the addition of K562 cells that do not express HLA molecules. However, other MHC-nonrestricted cytotoxic effector mechanisms such as IL-2–induced LAK activity may have contributed to the overall cytotoxicity and cross-reactivity of the CTL lines. In vivo, however, no cross-reactivity was observed and cross-combination–treated animals showed leukemic progression identical to animals receiving no CTLs. In addition to this observation, the effector cells that were recovered from treated mice exclusively displayed a CD3+TCRαβ+ immune phenotype and no CD3−CD56+ or CD3+TCRγδ+ cells were recovered although they were present in the administered CTL populations. These results indicate that for allogeneic CTLs, the MHC-restricted CD3+TCRαβ+ component present in the in vitro cultures represents the CTLs with the highest in vivo antileukemic efficacy and highest engraftment potential.

In conclusion, we have established an animal model for human immunotherapy in which the dynamics of CTL therapy can be studied in great detail. The first results obtained in this model demonstrated that MHC-restricted specificity that was imposed in vitro by repeated stimulation with the leukemic cells was maintained in vivo and instantaneously exerted an antileukemic effect after adoptive transfer. The results indicate that HLA-restricted CD3+TCRαβ+ CTLs displayed the highest in vivo antileukemic efficacy, and the combination of HLA class I– and II–restricted cytotoxicity was superior to an HLA class I–restricted cytotoxic response. However, the in vivo survival and expansion capacities of the transferred CTLs appeared to be compromised, and recovered CTLs showed diminished reactivity. The model offers the opportunity to study kinetics of CTL therapy and can be used to determine the optimal effector cell properties required for optimal in vivo engraftment and antileukemic efficacy of in vitro–expanded CTLs.

The authors wish to thank L. Leenheer from the Department of Pathology for preparing the spleen sections and for performing immunohistochemistry and Dr A. H. Zwinderman for advice on statistical evaluation.

Supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds) grant 2000-2213.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Bart A. Nijmeijer, Department of Hematology, Leiden University Medical Center, C2R, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: b.a.nijmeijer@lumc.nl.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal