Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a hematopoietic stem cell disorder in which clonal cells defective in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) biosynthesis are expanded, leading to complement-mediated hemolysis. PNH is often associated with bone marrow suppressive conditions, such as aplastic anemia. One hypothetical mechanism for the clonal expansion of GPI−cells in PNH is that the mutant cells escape attack by autoreactive cytotoxic cells that are thought to be responsible for aplastic anemia. Here we studied 2 model systems. First, we made pairs of GPI+ and GPI− EL4 cells that expressed major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and various types of ovalbumin. When the GPI-anchored form of ovalbumin was expressed on GPI+ and GPI− cells, only the GPI+cells presented ovalbumin to ovalbumin-specific CD4+ T cells, indicating that if a putative autoantigen recognized by cytotoxic cells is a GPI-anchored protein, GPI− cells are less sensitive to cytotoxic cells. Second, antigen-specific as well as alloreactive CD4+ T cells responded less efficiently to GPI− than GPI+ cells in proliferation assays. In vivo, when GPI− and GPI+ fetal liver cells, and CD4+ T cells alloreactive to them, were cotransplanted into irradiated hosts, the contribution of GPI− cells in peripheral blood cells was significantly higher than that of GPI+ cells. The results obtained with the second model suggest that certain GPI-anchored protein on target cells is important for recognition by T cells. These results provide the first experimental evidence for the hypothesis that GPI− cells escape from immunologic attack.

Introduction

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired hematopoietic stem cell disorder characterized by the presence of clonal blood cells deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)–anchored proteins. A somatic mutation of the PIGAgene, which is involved early in the biosynthesis of the GPI anchor,1 is responsible for the deficiency.1-3 Because GPI acts as a membrane anchor for many cell surface proteins,4 a loss of function ofPIGA results in the loss of all the GPI-anchored proteins from the blood cell surface. PIGA is X-linked; therefore, one hit of somatic mutation in PIGA causes GPI anchor deficiency in the hematopoietic stem cell.2 Clonal cells derived from the mutant hematopoietic stem cell occupy a big fraction of hematopoietic cells.5

The characteristic clinical triad of PNH includes hemolysis, venous thrombosis, and bone marrow failure.6,7 The activation of complement leads to the lysis of red blood cells deficient in the GPI-anchored proteins CD59 and CD55 that protect host cells from the attack by complement.4,5 An impaired regulation of complement activation may also be relevant to venous thrombosis.6,7 Bone marrow failure may be due to an autoimmune mechanism as thought to operate in idiopathic aplastic anemia (AA) that is often associated with PNH.6 7

Clonal expansion of cells derived from the mutant hematopoietic stem cell is critical for clinical manifestation of PNH. The mechanism, however, has not been elucidated. To test whether a defectivePIGA alone can cause the clonal expansion, we as well as Rosti and colleagues disrupted the mouse Piga gene, a homologue of PIGA, in embryonic stem cells and raised chimeric mice bearing GPI− cells.8,9 Because GPI-anchored proteins are essential for development,10mice with high chimerism did not survive. The analysis of a limited number of mice with very low levels of chimerism hardly showed the autonomous increase of GPI− cells. The chimeric mice, however, had GPI− cells in nonhematopoietic tissues, whereas patients with PNH have GPI− cells only in the hematopoietic system.

To overcome these problems, we made PNH model mice bearing GPI− cells only in the hematopoietic system by a combination of Cre/loxP-mediated disruption ofPiga in embryos and transplantation of their fetal liver cells into irradiated hosts. Analysis of these mice revealed that the percentage of GPI− cells remained constant; thePiga mutation alone does not account for the clonal expansion of the mutant stem cell and the second factor must be involved in the pathogenesis of PNH.11 The same conclusion was obtained from the different Cre/loxP-mediatedPiga-disrupted mice.12 The report that most healthy individuals have a small number of PIGAmutant granulocytes is consistent with this conclusion.13

Then, there have been 2 hypotheses about the second factor. One holds that the mutant clone itself gains an intrinsic ability to expand, a growth phenotype, by one or more additional genetic modifications. The other holds that the mutant clone is selected under the affected environment.6 As to the latter hypothesis, it was suggested that the affected environment may be an autoimmune process,14 because this is a widely accepted pathogenetic mechanism in idiopathic AA.15 The effector responsible in AA has not been clarified, but there are reports that CD4+T-cell clones capable of killing autologous hematopoietic progenitor cells can be generated by culturing T cells of AA patients with autologous hematopoietic progenitor cells.16,17 PNH, like AA, is reported to be strongly associated with the HLA haplotype DR218,19 and skewed usage of T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ genes.20 21 So, we assumed CD4+ T cells to be cytotoxic effectors that inhibit the hematopoiesis of normal stem cells. If this is true, there must be some difference in sensitivity to cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) between GPI+ and GPI−cells. Here, we test this hypothesis experimentally and, for the first time, show that the GPI− cell population could expand escaping CTL attack in an in vivo system.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice transgenic for ovalbumin (OVA)–specific TCR (termed OTII)22 were donated by Dr F. R. Carbone and W. R. Heath (Monash Medical School, and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Victoria, Australia). The Ly5.1 congeneic line of C57BL/6 (B6) mice was kindly provided by Dr H. Nakauchi (Tsukuba University, Ibaragi, Japan). B6 and B6.C-H2bm12/KhEg (bm12) mice were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) and the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), respectively. The experiments with mice included in this study were approved by the Review Board of the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University.

Peptides and antibodies

Peptide ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR (OVA323-339) was purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-Ly5.1, phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–heat-stable antigen (HSA), biotinylated anti–I-Abβ, -HSA, and -DX-5, allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD8 and streptavidin, and peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)–streptavidin were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti–Mac-1 (M1/70), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 53-6.7, and anti-TER119 were purified from each antibody-producing hybridoma (from Dr T. Kina, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) and biotinylated.

Cell lines

A vector for the expression of GPI-anchored OVA (GPI-OVA) was constructed by 4 parts ligation of an EcoRI-PstI fragment encoding the N-terminal signal sequence of human CD59, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified fragment corresponding to nucleotides 415-1161 of chicken OVA cDNA (to which PstI andXhoI sites were attached), anXhoI-NotI fragment encoding the human CD59 GPI attachment signal, and EcoRI- and NotI-cut pME18sf-neo, a mammalian expression plasmid. A vector for the expression of transmembrane OVA (TM-OVA) was constructed connectingEcoRI- and XbaI-cut pME18sf-neo, the same first 2 fragments used to generate the GPI-OVA vector, and a PCR-amplified fragment encoding a transmembrane region of human membrane cofactor protein (MCP; nucleotides 953-1203 of MCP cDNA of STBC/CYT2 allotype, a gift from Dr T. Seya, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka, Japan), to which XhoI and XbaI sites are attached. A vector pAc-Neo-OVA bearing native OVA cDNA was a gift from Dr T. Sato (Tokai University, Kanagawa, Japan). Expression vectors for I-Ab α and β chains were kindly provided by Dr L. Karlsson (R. W. Johnson Pharmaceutical Research Institute, San Diego, CA). A vector that expresses mouse Pigf cDNA was reported previously.23

We first stably transfected a Pigf-deficient clone of mouse thymoma cell line (EL4 Pigf−)24with vectors for I-Ab α and β chains and chose one clone with a high surface expression of I-Ab. We then stably transfected that clone with vectors expressing various types of OVA and selected one clone each. We further transfected the selected clones stably with either a Pigf-expressing or a control vector to obtain pairs of GPI+ and GPI−transfectants expressing various forms of OVA. To generate cells used in OVA-peptide pulse and allogeneic response experiments, the transfection with OVA-expression vector was omitted. To avoid clonal variation, the GPI+ and GPI− pairs were used as bulk populations. All the transfectants were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Cell purification

Highly purified CD4+ T cells (> 95% pure as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]) were prepared from pooled lymph nodes of OTII or bm12 mice by hypotonically lysing erythrocytes, followed by negative selection using the MACS system (cells treated with a cocktail of biotinylated anti-CD8, -HSA, -I-Abβ, and -B220 monoclonal antibodies [mAbs], followed by streptavidin beads; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany). Bone marrow cells, flushed from femurs, were depleted of lineage-marker positive cells by negative selection using the MACS system (cells treated with a cocktail of anti-CD4, -CD8, -B220, -Mac-1, and -DX-5 mAbs, followed by streptavidin beads).

In vitro T-cell proliferation

Purified CD4+ T cells from OTII or bm12 mice (3 × 105/well) were mixed with various types of EL4 transfectants (5 × 105/well) in flat-bottom 96-well plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mMl-glutamine, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The EL4 cells were pretreated with 50 μg/mL mitomycin C (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) for 1 hour and washed 3 times with the medium. For some experiments, they were pulsed with OVA peptides (5 or 10 μM). Proliferation was assessed on days 4 and 5 by pulsing cultures with [3H]thymidine for 4 hours.

In vivo experimental model of PNH

Mice transgenic for hCMV-Cre were generated in the B6 strain according to a previous report.25 Mice with aPiga gene bearing loxP sites within intron 5 and the 3′ flanking region (termed Pigaflox) were reported previously.26 The generation of Piga-disrupted hematopoietic stem cells using these 2 mouse strains was also reported.11 Briefly, we crossedPigaflox males with the hCMV-Cretransgenic females. All female embryos should be heterozygous forPigaflox and among them those that received theCre transgene would become heterozygous for Pigadisruption and mosaic for Pig-a expression due to random X inactivation. We collected fetal liver cells on 14 days after coitus (dac) as a source of stem cells and transferred them (3 × 106/mouse) intravenously into lethally irradiated B6 hosts (900 cGy irradiation from a 137Cs source). We cotransplanted them with or without purified CD4+ T cells of bm12 mice (7.5 × 104 cells/mouse) together with lineage marker–negative bm12 bone marrow cells (106cells/mouse) to prevent death from aplasia.27 To distinguish fetal liver–derived cells from other cells, we used mice whose Ly5 allele was 5.1 for the donor of fetal liver and 5.2 for the host and bm12 mice. Flow cytometric analysis of the peripheral blood cells of these chimeric mice was reported previously.11

Results

We tested 2 models to obtain experimental evidence for the hypothesis that expansion of the GPI− cell population seen in PNH is caused by survival of GPI− cells in the presence of autoreactive T cells.6,14 We focused on CD4+ T cells.28 In the first model, we tested a specialized situation where a putative autoantigen recognized by CD4+ T cells is derived from GPI-anchored proteins (Figure1A). In the second model, we tested whether a lack of GPI-anchored proteins on antigen-presenting cells (APCs; or target cells) affects stimulation of (or recognition by) CD4+ T cells (Figure 1B).

Two experimentally tested models.

(A) A putative autoantigen recognized by CD4+T cells is derived from GPI-anchored proteins. GPI+ cells (left) process GPI-anchored proteins and present antigenic peptides on MHC class II molecules, whereas GPI− cells (right) do not present such antigenic peptides. (B) Some GPI-anchored protein is a ligand for some costimulatory molecules on CD4+ T cells. GPI+ cells (left) efficiently stimulate CD4+ T cells, whereas GPI− cells (right) do not.

Two experimentally tested models.

(A) A putative autoantigen recognized by CD4+T cells is derived from GPI-anchored proteins. GPI+ cells (left) process GPI-anchored proteins and present antigenic peptides on MHC class II molecules, whereas GPI− cells (right) do not present such antigenic peptides. (B) Some GPI-anchored protein is a ligand for some costimulatory molecules on CD4+ T cells. GPI+ cells (left) efficiently stimulate CD4+ T cells, whereas GPI− cells (right) do not.

Cells defective in GPI biosynthesis are unable to present antigenic peptides of GPI-anchored proteins on MHC class II molecules

To test whether antigenic peptides derived from endogenous GPI-anchored proteins are presented on MHC class II molecules and if so whether the presentation is dependent on GPI anchoring, we used the GPI-anchored form of OVA as a model antigen. We isolated CD4+ T cells from lymph nodes of OTII mice that express transgenic TCR specific for an OVA-derived peptide presented on I-Ab molecules. These T cells were stimulated with GPI+ and GPI− EL4 cell lines expressing I-Ab and various forms of OVA. We first used TM-OVA to confirm that the GPI− EL4 cell line is able to present peptides derived from OVA on I-Ab molecules. The GPI− EL4 cell line expressing TM-OVA (shaded bar) stimulated the CD4+ T cells (Figure2). The efficiency was about one third that of the GPI+ EL4 cell line expressing TM-OVA (black bar; 34 000 versus 90 000 cpm; Figure 2). We then tested the presentation of OVA peptides derived from GPI-OVA. The GPI+EL4 cell line expressing GPI-OVA stimulated the CD4+ T cells (black bar), indicating that antigenic peptides derived from GPI-anchored proteins can be presented on MHC class II molecules. In contrast, GPI− EL4 transfected with the same cDNA encoding GPI-OVA did not stimulate the CD4+ T cells (shaded bar). The same GPI− EL4 stimulated the CD4+ T cells when exogenous OVA peptides were added (white bar), confirming that GPI− EL4 had an intact machinery for MHC class II–dependent antigen presentation. Therefore, cells defective in GPI anchor biosynthesis are not able to present antigenic peptides of GPI-anchored proteins on MHC class II molecules.

GPI anchor–negative cells do not present antigenic peptides of GPI-anchored proteins on MHC class II molecules.

CD4+ T cells isolated from a TCR-transgenic mouse (OTII) were mixed with EL4 cells transfected with various forms of OVA and treated with mitomycin C. Proliferation was assessed on day 4. TM-OVA indicates EL4 cells transfected with the transmembrane form of OVA; GPI-OVA, EL4 cells transfected with GPI-anchored OVA; native OVA, EL4 cells transfected with native OVA; vector, vector-transfected EL4 cells; ▨, EL4 cells defective in GPI anchor biosynthesis; ▪, EL4 cells with normal GPI anchor biosynthesis; and ■, GPI− EL4 cells pulsed with OVA peptide. Data (mean + SD of duplicate samples) were from a representative of 7 experiments, all with similar results.

GPI anchor–negative cells do not present antigenic peptides of GPI-anchored proteins on MHC class II molecules.

CD4+ T cells isolated from a TCR-transgenic mouse (OTII) were mixed with EL4 cells transfected with various forms of OVA and treated with mitomycin C. Proliferation was assessed on day 4. TM-OVA indicates EL4 cells transfected with the transmembrane form of OVA; GPI-OVA, EL4 cells transfected with GPI-anchored OVA; native OVA, EL4 cells transfected with native OVA; vector, vector-transfected EL4 cells; ▨, EL4 cells defective in GPI anchor biosynthesis; ▪, EL4 cells with normal GPI anchor biosynthesis; and ■, GPI− EL4 cells pulsed with OVA peptide. Data (mean + SD of duplicate samples) were from a representative of 7 experiments, all with similar results.

When GPI anchors are not attached to proteins that are normally GPI anchored, the proteins are not expressed on the cell surface due either to degradation in the cytoplasm or to secretion into the extracellular space.4 Peptides generated in the cytoplasm would not be presented on MHC class II molecules. To test whether OVA destined for extracellular secretion is presented on MHC class II molecules, we used GPI+ and GPI− EL4 cells expressing native-secreted OVA (native OVA in Figure 2). The antigenic peptide was not presented on class II molecules irrespective of the presence of GPI (shaded and black bars). Taken together with the above result that GPI− cells presented OVA peptide from TM-OVA, it is suggested that the cell surface expression of GPI-anchored proteins is required for the presentation of antigenic peptides on MHC class II molecules. These results indicate that if a putative autoantigen recognized by CD4+ T cells is derived from GPI-anchored proteins, GPI anchor–deficient cells would be more insensitive to CD4+ T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity than GPI anchor–sufficient cells.

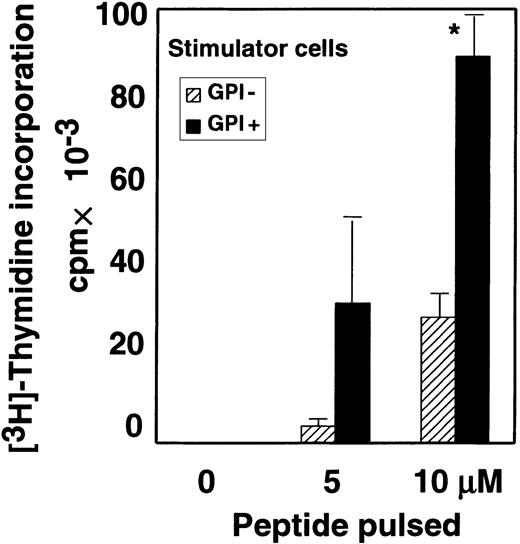

GPI-anchored protein-negative cells are less efficient than GPI-anchored protein-positive cells in MHC class II–mediated stimulation of CD4+ T cells

As described above, the GPI− EL4 cell line presented TM-OVA–derived peptide significantly but less efficiently than the GPI+ counterpart (TM-OVA in Figure 2). FACS analysis showed that the surface expression of TM-OVA and I-Ab on these 2 cell lines was similar (mean fluorescent channels of GPI+and GPI− cells were 295 and 245 for TM-OVA, and 115 and 145 for I-Ab, respectively.). Considering that a number of GPI-anchored proteins are involved in cell-to-cell interactions, we next compared the stimulation of CD4+ T cells in the presence and absence of GPI-anchored proteins on APCs. To eliminate the intracellular antigen-processing step, we compared GPI+ and GPI− EL4 cell lines that express I-Abmolecules but not TM-OVA. These cell lines were pulsed with various concentrations of OVA peptides and then tested for their ability to stimulate CD4+ T cells from OTII mice. Stimulation of CD4+ T cells by GPI− cells was significantly weaker than that by the GPI+ counterpart (Figure3). These results suggest that GPI-anchored proteins costimulate antigen presentation by enhancing cell-to-cell interaction and that GPI− cells would be less sensitive to cytotoxic CD4+ T cells.

Some GPI-anchored proteins on APCs facilitate interaction with T cells.

Purified OTII-CD4+ T cells were incubated with I-Ab–expressing EL4 cells pulsed with various concentrations of OVA peptide. Data represent 1 of 2 experiments. ▨ indicates EL4 cells defective in GPI anchor biosynthesis; ▪, EL4 cells with normal GPI anchor biosynthesis; and *, difference significant (P < .05) as determined with the Studentt test.

Some GPI-anchored proteins on APCs facilitate interaction with T cells.

Purified OTII-CD4+ T cells were incubated with I-Ab–expressing EL4 cells pulsed with various concentrations of OVA peptide. Data represent 1 of 2 experiments. ▨ indicates EL4 cells defective in GPI anchor biosynthesis; ▪, EL4 cells with normal GPI anchor biosynthesis; and *, difference significant (P < .05) as determined with the Studentt test.

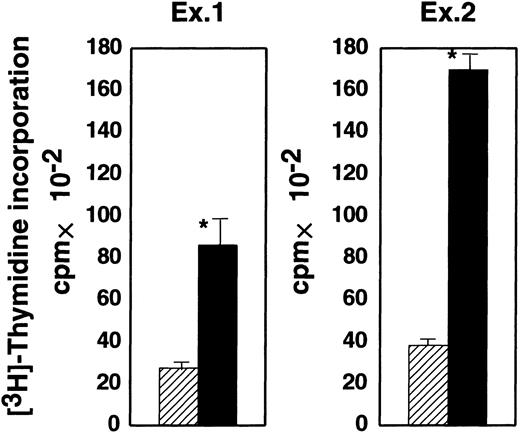

GPI− cells stimulate allogeneic CD4+ T cells less efficiently than GPI+ cells in a proliferation assay

The bm12 mouse has a mutation in the I-Abβ gene. CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice are allogeneic to cells bearing wild-type I-Ab molecules.29 We compared the proliferative response of bm12 CD4+ T cells to GPI− and GPI+ EL4 cells expressing I-Ab (shaded and black bars, respectively, in Figure4). The response of CD4+ T cells was much weaker to GPI− EL4 than GPI+EL4 cells (2900 versus 8000 cpm in experiment 1 and 3800 versus 17 000 cpm in experiment 2). Therefore, GPI-anchored proteins on stimulator cells are important for the activation of CD4+ T cells in the allogeneic response.

GPI− EL4 cells were less efficient in proliferative activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells than GPI+ EL4 cells.

Purified CD4+ T cells from a bm12 mouse were incubated with GPI− (shaded) and GPI+ (black), I-Ab–expressing EL4 cells. Proliferation was assessed on day 4. Two similar experiments are shown; ▨ indicates GPI−; ▪, GPI+; and * indicates difference significant (P < .05).

GPI− EL4 cells were less efficient in proliferative activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells than GPI+ EL4 cells.

Purified CD4+ T cells from a bm12 mouse were incubated with GPI− (shaded) and GPI+ (black), I-Ab–expressing EL4 cells. Proliferation was assessed on day 4. Two similar experiments are shown; ▨ indicates GPI−; ▪, GPI+; and * indicates difference significant (P < .05).

GPI− multipotential hematopoietic cells could escape CTL attack in vivo

Based on the result regarding the allogeneic response in vitro, we next established an in vivo experimental system to compare the susceptibilities of GPI+ and GPI−hematopoietic cells to cytotoxic T cells. There is a report that the transfer of a small number of CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice to lightly irradiated B6 mice causes lethal pancytopenia due to a severe graft-versus-host reaction in bone marrow.27 We transplanted a mixture of GPI+ and GPI− fetal liver cells of B6 background as a source of hematopoietic stem cells into lethally irradiated B6 mice with or without CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice as a source of CTLs (Figure5). To prevent the death of the recipient mice from aplasia, lineage marker–negative bone marrow cells of bm12 mice were also cotransplanted. The cells derived from fetal liver cells were Ly5.1+, whereas bm12 mice and recipient mice were Ly5.2+.

In vivo experimental system to test resistance of GPI anchor–defective hematopoietic cells to cytotoxic cells.

Pigaflox males were crossed withhCMV-Cre transgenic females. Female embryos that had theCre transgene became heterozygous for the Pigadisruption and mosaic for Piga expression due to random X inactivation. Fetal liver cells of the mosaic embryos on 14 dac were transferred to lethally irradiated B6 recipients together with lineage marker–negative bone marrow cells of bm12 mice, with or without purified CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice. To distinguish fetal liver–derived cells from recipient-derived and bm12 bone marrow–derived cells, mice with the Ly5.1 allele were used as a source of fetal livers and mice with the Ly5.2 allele were used for the recipients and as a source of bone marrow.

In vivo experimental system to test resistance of GPI anchor–defective hematopoietic cells to cytotoxic cells.

Pigaflox males were crossed withhCMV-Cre transgenic females. Female embryos that had theCre transgene became heterozygous for the Pigadisruption and mosaic for Piga expression due to random X inactivation. Fetal liver cells of the mosaic embryos on 14 dac were transferred to lethally irradiated B6 recipients together with lineage marker–negative bone marrow cells of bm12 mice, with or without purified CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice. To distinguish fetal liver–derived cells from recipient-derived and bm12 bone marrow–derived cells, mice with the Ly5.1 allele were used as a source of fetal livers and mice with the Ly5.2 allele were used for the recipients and as a source of bone marrow.

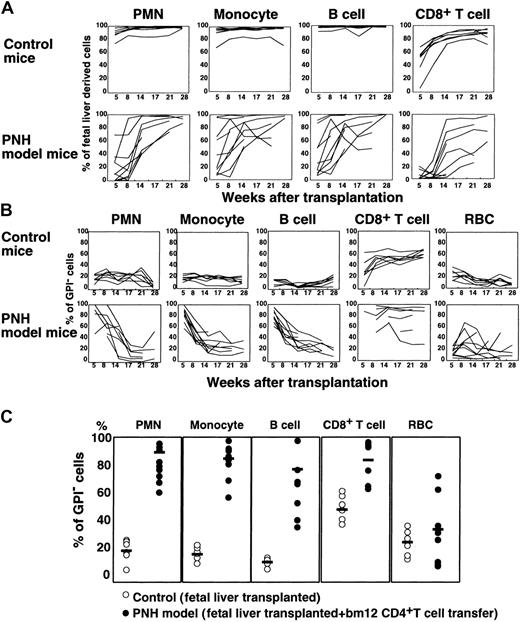

At 5 to 28 weeks after transplantation, we determined percentages of GPI− cells in Ly5.1+ cells of various blood cell lineages to see whether GPI− cells escaped from CTL attack (Figure 6). In mice without CD4+ T cells, Ly5.1+ fetal liver–derived cells dominated in the blood, most likely because syngeneic fetal liver cells were more efficient than allogeneic bone marrow cells in engraftment (control mice in Figure 6A). GPI− cells in polymorphonuclear cells (PMNCs) and monocytes numbered about 20% (control mice in Figure 6B). When CD4+ T cells were cotransplanted (PNH model mice in Figure 6A), percentages of fetal liver–derived cells in PMNCs and monocytes were lower at 5 and 8 weeks (lower than 20% in some mice), indicating that bm12 CD4+ T cells killed a large number of B6 fetal liver–derived cells. Under these conditions, percentages of GPI− cells in PMNCs and monocytes were markedly increased at 5 and 8 weeks (nearly 100% in some mice; Figure 6B-C), indicating that GPI+ cells were selectively killed. In B cells, the contribution of GPI−cells in the absence of CD4+ T cells was lower than in myeloid cells (about 10% versus 20%, control mice in Figure 6B) consistent with our previous report.11 Nevertheless, in the presence of CD4+ T cells, the percentage of GPI− cells became very high (PNH model mice in Figure 6B-C) with a decrease of fetal liver–derived B cells (Figure 6A) at 5 and 8 weeks, again showing selective elimination of GPI+cells. In CD8+ T cells, fetal liver–derived cells appeared slower than in other cell types (control mice in Figure 6A) but the percentage of GPI− cells was higher (Figure 6B) consistent with our report.11 In the presence of allogeneic CD4+ T cells, the percentage of fetal liver–derived CD8+ T cells decreased markedly at 8 weeks (Figure 6A), whereas the percentage of GPI− CD8+ T cells increased (Figure 6B-C). Due to a lack of Ly5 expression, erythrocytes derived from B6 fetal liver cannot be distinguished from those derived from bm12 bone marrow. The percentage of GPI− erythrocytes in the absence of CD4+ T cells was 10% to 40% at 5 to 14 weeks (control mice in Figure 6B). It increased in some mice in the presence of CD4+ T cells, however, not significantly (Figure 6B-C). These results indicate that GPI−multipotential hematopoietic cells are more resistant to CTL attack.

GPI− multipotential hematopoietic cells can escape CTL attack.

(A) Percentages of Ly5.1+ fetal liver–derived cells in various blood cells of individual mice were shown as a function of weeks after transplantation. Upper panels, control mice (n = 7) that received transplants of GPI+ and GPI−fetal liver cells, and lineage marker–negative bm12 bone marrow cells; lower panels, experimental mice (n = 9) that received transplants of fetal liver cells and lineage marker–negative bm12 bone marrow cells together with CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice. (B) Percentages of GPI− cells in fetal liver–derived cells of various blood cell types plotted as a function of weeks after transplantation. Control and experimental mice were the same as those in panel A. (C) Percentages of GPI− cells in various blood cell lineages determined 5 and 8 weeks after transplantation are shown (data for PMNCs and monocytes are at 5 weeks and for B and T cells and erythrocytes are at 8 weeks). ○ indicates control mice (n = 7); ●, experimental mice (n = 9). Bars represent mean percentages.

GPI− multipotential hematopoietic cells can escape CTL attack.

(A) Percentages of Ly5.1+ fetal liver–derived cells in various blood cells of individual mice were shown as a function of weeks after transplantation. Upper panels, control mice (n = 7) that received transplants of GPI+ and GPI−fetal liver cells, and lineage marker–negative bm12 bone marrow cells; lower panels, experimental mice (n = 9) that received transplants of fetal liver cells and lineage marker–negative bm12 bone marrow cells together with CD4+ T cells from bm12 mice. (B) Percentages of GPI− cells in fetal liver–derived cells of various blood cell types plotted as a function of weeks after transplantation. Control and experimental mice were the same as those in panel A. (C) Percentages of GPI− cells in various blood cell lineages determined 5 and 8 weeks after transplantation are shown (data for PMNCs and monocytes are at 5 weeks and for B and T cells and erythrocytes are at 8 weeks). ○ indicates control mice (n = 7); ●, experimental mice (n = 9). Bars represent mean percentages.

In mice that received cotransplantations with CD4+T cells, percentages of fetal liver–derived cells increased with time (Figure 6A) in association with a decrease in the percentage of GPI− cells (Figure 6B). Both percentages were similar to those in the control mice without bm12 CD4+ T cells at 21 weeks after transplantation. Therefore, GPI+ multipotential hematopoietic stem cells of fetal livers were not eliminated by bm12 CD4+ T cells and on decline of the allogeneic CD4+ T cells provided GPI+ progeny in blood. This indicates that multipotential hematopoietic progenitors but not stem cells express MHC class II I-A molecules and are sensitive to allogeneic CD4+ T cells. This again indicates that expansion of the GPI− cell population occurred only under selection by allogenic T cells. The results in this mouse model support the idea that if autoimmune cytotoxic CD4+ T cells recognize multipotential hematopoietic cells, GPI− cells would survive and expand.

Discussion

This study presents the first experimental evidence that supports the immunologic selection hypothesis for the clonal expansion of PNH cells. Especially, it was demonstrated that GPI−hematopoietic cells become dominant in model mice on selection by allogeneic CD4+ T cells (Figure 6). Until now there has been only clinical evidence for the immunologic selection hypothesis. The frequent association of PNH with AA,30,31 taken together with the presence of PIG-A mutant blood cells in most healthy individuals,13 has been the basis of the suggestion that an autoimmune process promotes clonal expansion. We assumed CD4+ T cells to be cytotoxic effectors and established 3 experimental systems to test 2 hypothetical mechanisms of the immunologic selection (Figure 1). First, we tested a specialized situation in which the antigen recognized by CD4+ T cells is derived from GPI-anchored protein (Figure 1A) and showed that GPI+ APCs present the antigen derived from GPI-anchored proteins on MHC class II molecules, whereas GPI− APCs do not (Figure 2). GPI-anchored proteins like other cell surface transmembrane proteins would reach, via the endocytic pathway, a compartment where proteins are processed for presentation on MHC class II molecules. Proteins normally GPI anchored are not expressed on the surface of GPI− APCs; hence, there is no presentation on the MHC class II molecules. Our data suggest that if the relevant autoantigen is derived from GPI-anchored proteins, PNH cells may be resistant to CD4+ CTL (Figure 1A).

Second, we demonstrated using in vitro systems that GPI−APCs do not stimulate antigen-specific and allogeneic CD4+T cells efficiently (Figures 3 and 4). We think that some GPI-anchored protein on APCs acts as a ligand for costimulatory molecules on T cells (Figure 1B). A candidate molecule is CD48 that is expressed on the surface of APCs and interacts with CD2 on T cells. An experiment using CD48 knockout mice revealed that the alloresponse of CD4+ T cells was significantly lower without CD48 on the surface of APCs.32 Indeed, GPI+ EL4 cells used as model APCs in our experiments expressed CD48, whereas GPI− EL4 cells did not (data not shown). Because CD2 is widely expressed on T cells, costimulation mediated by interaction of CD48 and CD2 would be involved in our in vitro experimental systems.

Third, using allogeneic CD4+ T cells in a transplantation system, we demonstrated the expansion of the GPI− hematopoietic cell population in vivo on selection by T cells (Figure 6). In this system, the expansion was seen only transiently. Both GPI+ and GPI− multipotential hematopoietic stem cells were spared and when allogeneic T cells declined, the dominance of GPI− cells disappeared. It is most likely that the mouse stem cells derived from fetal liver do not express MHC class II I-A molecules and the selection occurred in the multipotential hematopoietic progenitors that presumably express I-A+.27 In this regard, this mouse model is different from AA where multipotential hematopoietic stem cells are a target of autoimmunity. However, it is likely that MHC class II molecules are expressed on the multipotential hematopoietic stem cells in patients with AA because interferon γ, which induces MHC class II expression in various cells,33 is expressed in cells from patients with AA.28 Also, there is a report that human multipotential hematopoietic stem cells express HLA-DR.34 Therefore, the multipotential hematopoietic stem cells could be recognized by CD4+ T cells in a human system.

As shown in our mouse system, expansion of the GPI−population due to selection at the progenitor level is reversible if the stem cells are spared; when the CTLs are present, GPI−cells would continuously proliferate and when CTLs disappear, the expansion would also stop. It is possible that some of the reported patients with PNH with spontaneous remission were mediated by a similar mechanism.35 The candidate GPI-anchored protein responsible for the selection in our mouse model would be CD48 because Blazar and colleagues reported that when bm12 CD4+ T cells were transplanted into lightly irradiated B6 mice, the death of recipient mice due to aplasia was nearly completely prevented by infusion of anti-CD48 mAbs.36 Human CD48 is also GPI anchored. Although human CD48 does not bind CD2 with high affinity, it binds to CD244 2B4, a recently identified costimulatory molecule on T cells.37 38

The PNH cells are present in a large proportion of AA patients.39,40 Although the percentage of GPI− cells is higher in AA patients than healthy individuals, the cells are frequently stable and do not reach a size big enough to cause the clinical manifestation of PNH.39GPI− cells stimulate T cells less efficiently, but the stimulation is not completely abolished. It is possible that under strong marrow-damaging conditions, expansion may be limited. When the patients are treated with immunosuppressive therapies, such as antithymocyte globulin or cyclosporin A, and if the therapeutic effect is partial, GPI− cells may proliferate selectively, resulting in the development of PNH. If the therapy is very effective, selection may disappear, leading to the growth of GPI+cells and remission of AA.40

We are not proposing that selection is the only mechanism of clonal expansion in PNH. The 2 hypotheses (see “Introduction”) are not mutually exclusive and both may be operating. We think that selection may not be sufficient for high-level expansion of the PIG-Amutant clone seen in so-called florid PNH. Such a clone may have a growth phenotype, like benign tumors, owing to additional cytogenetic abnormalities. Consistent with this idea, there is a recent report that the early growth response gene (EGR1), a zinc finger transcription factor, is up-regulated in all cases of PNH studied.41 When immunologic damage occurs in a pool of hematopoietic stem cells, the surviving GPI− stem cells would be forced to proliferate. Then the possibility of a second genetic abnormality increases, resulting in the generation of a subclone having a growth phenotype. Up-regulation of EGR1 may be due to a genetic abnormality other than the PIGA somatic mutation. It is well known that some patients with PNH eventually develop acute myelogenous leukemia from within the PNH clone.6 It is conceivable that the further accumulation of genetic abnormalities in a benign tumorlike subclone leads to the generation of a leukemic clone.

The identification of GPI-anchored proteins responsible for the immunologic selection, the demonstration of the target protein that is recognized by autoreactive CTLs in PNH, and the search for additional cytogenetic abnormalities responsible for the growth phenotype are critical to further understand clonal expansion in PNH.

We thank Drs F. R. Carbone, H. Nakauchi, T. Sato, L. Karlsson, T. Seya and T. Kina for their gifts, Dr W. Hazenbos for discussion, Dr Shuichi Yamada for generating transgenic mice, and Keiko Kinoshita and Fumiko Ishii for technical assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 18, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1669.

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Taroh Kinoshita, Department of Immunoregulation, Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, 3-1 Yamada-oka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan; e-mail:tkinoshi@biken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal