Abstract

Recombination activating gene-1 (RAG-1) andRAG-2 are expressed in lymphoid cells undergoing the antigen receptor gene rearrangement. A study of the regulation of the mouse RAG-2 promoter showed that the lymphocyte-specific promoter activity is conferred 80 nucleotide (nt) upstream of RAG-2. Using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay, it was shown that a B-cell–specific transcription protein, Pax-5, and a T-cell–specific transcription protein, GATA-3, bind to the −80 to −17 nt region in B cells and T cells, respectively. Mutation of the RAG-2 promoter for Pax-5– and GATA-3–binding sites results in the reduction of promoter activity in B cells and T cells. These results indicate that distinct DNA binding proteins, Pax-5 and GATA-3, may regulate the murine RAG-2 promoter in B and T lineage cells, respectively.

Recombination activating gene-1 (RAG-1)1 and RAG-2 are the essential and tissue-specific components of the V(D)J recombination.1,2 It has been demonstrated that these genes are sufficient for the recognition and initial cleavage of DNA containing recombination signal sequences.3-6 Disruption of either RAG-1 or RAG-2 in the germline of a mouse completely prevented the rearrangement of immunoglobulin (Ig) and T cell receptor (TCR) genes and blocked the development of mature B and T lymphocytes.7,8 It has also been shown that the mutation of human RAG-1 or RAG-2caused severe combined immunodeficiency without B lymphocytes9 and Omenn syndrome with a few antigen repertoires of lymphocytes.10

RAG-1 and RAG-2 expressions are lymphoid-specific and are regulated developmentally.11,12RAG-1 andRAG-2 are expressed in pro-B cells or pro-T cells in a concordant manner when rearrangement of the IgH or TCRβchain gene occurs. Secondary expression of RAG-1 andRAG-2 occurs when the IgL or TCRα chain loci undergo VJ rearrangement to produce mature B or T cells. Recently it has been demonstrated that antigen stimulation induces reexpression ofRAG-1 and RAG-2 in mature lymphocytes in peripheral lymphoid organs,13-15 which indicates that RAG-1and RAG-2 play a role in editing the lymphocyte repertoire in the periphery.16

We and others have been studying the transcriptional regulation of the RAG gene.17-19 It has been shown that the 5′ flanking region of the human RAG-1 gene functions as a minimal promoter, but it does not confer lymphocyte-specific expression of RAG-1. Concerning the lymphocyte-specificity and differentiation stage–specificity of the RAG-1 expression, it has been demonstrated that alteration of the chromatin structure detected by deoxyribonucelase I (DNase I) hypersensitivity takes place in accordance with the RAG-1 expression.19 20 In this report we describe the lymphocyte-specific promoter activity of the mouse RAG-2 5′ flanking region and demonstrate that distinct lymphoid-specific transcriptional factors are required for activation of the murine RAG-2 promoter in B and T lymphocytes.

Materials and methods

Isolation of mouse RAG-2 genomic clones

Mouse RAG-2 genomic clones were isolated from a λ FIX II library (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and screened by using a radio-labeled full-length mouse RAG-2 complementary DNA (cDNA)1 as described previously.17 Several clones were isolated, and 2 of them (mRAG-2-4 and mRAG-2-6) were analyzed by restriction enzyme mapping and DNA sequencing (Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing FS Ready Reaction Kit; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA).

5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE)

5′ RACE was performed (5′ RACE System; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, poly-A+ RNA was prepared from thymocytes and reverse transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT) for 50 minutes at 42°C with 2.5 pmoles of gene-specific primer 1 (GSP1) located at 392-412 base pair (bp) of mouse RAG-2 cDNA1 (5′-GAG TCT ATG CTG CCT TTG TA-3′). After ribonuclease (RNase) H digestion, cDNA was purified with GLASSMAX spin cartridge and tailed with deoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate (dCTP) using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. The cDNA was subsequently amplified in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using an anchor primer and GSP2, which is located at 165-184 bp of mouse RAG-2 cDNA (5′-CAU CAU CAU CAU TGA CCC ACT GTT ACC ATC TG-3′). PCR conditions included 1 cycle of 2 minutes at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of 0.5 minutes at 94°C, 0.5 minutes at 55°C, 2 minutes at 72°C, and finally an extension for 7 minutes at 72°C. The amplified products were subcloned into pT7Blue-T vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and subjected to DNA sequencing analysis as described above.

Cell lines and cell culture

The following cell lines were used for transfection or preparation of nuclear extracts: 18.8.1 (pre–B cell, RAG-2+),21 BAL17 (B cell, RAG-2+), and WEHI279 (B cell, RAG-2−)22 (gift of K Sakaguchi, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan); WEHI231 (B cell, RAG-2−)21 and M1 (myeloid, RAG-2−) (gift of Dr H. Kikutani, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan); LSB11-1 (T cell, RAG-2+)21; EL4 (T cell, RAG-2−)21; 110TC (T cell, RAG-2−)21; WEHI3 (myeloid, RAG-2−)22; L (fibroblast, RAG-2−); and NIH3T3 (fibroblast, RAG-2−). Expression of RAG-2 mRNA in the cell lines was examined by RT-PCR as described by Chun et al.23 All cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide (CO2).

Construction of plasmids

RAG-2 promoter fragments were generated by PCR using the cloned genomic DNA as a template; the oligonucleotide 1 as a common 3′ primer; and the oligonucleotides 2 (−639 to +147 nt genomic DNA fragment [−639/+147]), 3 (−430/+147), 4 (−86/+147), and 5 (−41/+147) as 5′ primers. Amplified fragments were cloned into the pT7Blue-T vector. The fragments were then cut out by digesting with NcoI and SalI restriction enzymes and reinserted into the NcoI and XhoI restriction enzyme sites of the PicaGene basic vector 2 or enhancer vector 2 (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). To prepare the luciferase construct with either the −251/+147 or +44/+147 fragment, the luciferase construct with the −430/+147 fragment was digested with either restriction enzymesNdeI and HindIII or NdeI and PstI and then blunt-end ligated. Mouse βTCR 3′ enhancer24was cloned into the SpeI and KpnI restriction enzyme sites of the luciferase constructs in the PicaGene basic vector 2.

For preparation of the −86/+147 fragment with a mutation for a Pax-5 binding site (M2 mutation), the −86/−17 fragment with the M2 mutation was prepared by PCR using the cloned genomic DNA as a template and primers 6 and 7, and the −33/+147 fragment with the M2 mutation was prepared using primers 1 and 8. The −86/+147 fragment with the M2 mutation was amplified using both the −86/−17 fragment with the M2 mutation and the −33/+147 fragment with the M2 mutation as templates and primers 1 and 4. The −86/+147 fragment with mutation for the GATA binding site was prepared by PCR using the cloned genomic DNA as a template and primers 1 and 9.

Transfection and luciferase assay

For transfection of luciferase constructs into cells other than fibroblasts, the DEAE dextran method was used. Briefly, 5 × 106 cells were incubated in 1 mL 0.5 mg/mL diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) dextran (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in Tris-buffered (tris[hydroxymethyl] aminomethane–buffered) saline containing 5 μg luciferase reporter gene and 5 μgpSRα-lacZ gene17 for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS and 100 μmol/L chloroquine (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) for 60 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then spun down and reincubated in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS at 37°C. For transfection into fibroblasts, the calcium phosphate method was used. Briefly, DNA precipitation was prepared by adding 456 μL DNA solution containing 15 μg luciferase reporter gene, 15 μgpSRα-lacZ gene, and 0.25 mol/L calcium dichloride (CaCl2) into 456 μL 0.05 mol/L HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.1), 0.28 mol/L sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.7 mmol/L sodium dihydrogenphosphate (NaH2PO4), and 0.7 mmol/L disodium hydrogenphosphate (Na2HPO4). After 30 minutes incubation at room temperature, the DNA precipitate was added evenly over a 10-cm plate of cells in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (D-MEM) containing 10% FCS. Cells were harvested 22-24 hours after transfection, and luciferase activity and β-galactosidase activity was measured as described previously.17

The luciferase constructs used for the luciferase reporter gene assay contained either the βTCR enhancer or SV40 enhancer to augment the transcriptional activity. This was done because a genomic DNA fragment spanning from the −1.1 kb to +147 nt or its truncated fragments linked upstream of the luciferase gene showed undetectable luciferase activity in the absence of an enhancer region in any cell lines including the RAG-2–expressing lymphocyte cell lines. The constructs with the βTCR enhancer were introduced into RAG-2–expressing (LSB11-1, 18.8.1, or BAL17) cell lines or RAG-2–nonexpressing (EL4 or 110TC) lymphoid cell lines. The constructs with the SV40 enhancer were introduced into nonlymphoid cell lines (L and NIH3T3) as well as 18.8.1, a pre–B cell line.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed according to the method described by Schreiber et al.25 The following fragments were used as a probe DNA: −80/−17 fragment, −85/−56 fragment, or the fragment containing the tandemly repeated GATA binding sequence. The probe DNA was labeled with α-32P-dATP by filling with the Klenow fragment. Nuclear extracts (2 μL) were incubated with the 32P-labeled probe DNA at room temperature for 20 minutes in 15 μL reaction mixture containing 4% Ficoll 400 (Pharmacia), 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.9), 50 mmol/L potassium chloride (KCl), 1 mmol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1 mmol/L dithiothreital (DTT), 0.25 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 1-2 μg poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia). After incubation samples were loaded onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel, which was prerun for 1 hour at 4°C (100 V) in Tris-glycine buffer and electrophoresed at 4°C (100 V) for 2-3 hours. The gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan). For preparation of nuclear extracts containing recombinant GATA-3, an expression vector for mouse GATA-3 cDNA (gift of Dr M. Yamamoto, Tsukuba University, Tsukuba, Japan) was transfected into 293T cells by a calcium phosphate method, and nuclear extracts were prepared 24 hours after transfection.

Where indicated, competitor DNA or antibodies to transcription factors (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were added to the binding reaction. Competitor DNA was prepared by PCR using the following primer pairs (fragments): 6/10 (−80/−17), 6/11 (−80/−42), 6/12 (−80/−30), 13/12 (−65/−30), 13/10 (−65/−17), or 14/10 (−51/−17). For preparation of the mutated −80/−17 fragment, the following primer pairs (fragments) were used: 6/15 (−80/−17M1), 6/7 (−80/−17M2), 6/16 (−80/−17M3), or 6/17 (−80/−17M4). Consensus binding sequences of c-Myb, Ikaros,26 GATA-3, or Pax-5 or mutated binding sequences of Pax-527 were prepared by annealing oligonucleotides of 18/19, 20/21, 22/23, 24/25, or 26/27 primer pairs, respectively. Fragments −85/−56 or −85/−56 with mutation for a GATA binding site were prepared by annealing oligonucleotides of 28/29 or 9/30 primer pairs.

Oligonucleotides

The following oligonucleotides were used in this study: 1, 5′-GGGGTACCATGGCCAGAGGGGCTGCTTATC-3′; 2, 5′-CCATCTAAGCTTTGTGGAAG-3′; 3, 5′-CCTGTATTCACAGGCATCAC-3′; 4, 5′-TTCTGTCTCCCTCAACCATC-3′; 5, 5′-AGGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCC-3′; 6, 5′-GCTCTAGATCTCCCTCAACCATCACAGG-3′; 7, 5′-TAACGTTCG- TAACTGACTGTGACCTC-3′; 8, 5′-GTCAGTTACGAACGTTACACCAGTACAC-3′; 9, 5′-TTCTGTCTCCCTCAACCAAGACAGGGGTGC-3′; 10, 5′-GCTCTAGATAACGGGAGTAACTGAC-3′; 11, 5′-GCCTTCCCCCTCCCTGCACCC-3′; 12, 5′-TGACTGTGACCTCCTTCCCC-3′; 13, 5′-ACAGGGGTGCAGGGAGGGGGAA-3′; 14, 5′-AGGGGGAAGGAGGTCACAGT-3′; 15, 5′-TACATGGAGTAACTGACTGTGAC-3′; 16, 5′-TAACGGGATGCACTGACTGTGACCTCCTT-3′; 17, 5′-TAACG-GGAGTACAGGACTGTGACCTCCTT-3′; 18, 5′-TACAGGCATAACGGTTCCGTAGT-GA-3′; 19, 5′-TCACTACGGAACCGTTATGCCTGTA-3′; 20, 5′-GTTTCCATGACATCATGATGGGGGT-3′; 21, 5′-ACCC- CCATCATGATGTCATGGAA-3′; 22, 5′-CACTTGATAACAGAAAGTGATAACTCT-3′; 23, 5′-AGAGTTATCACTTTCTGTTATCAAGTG-3′; 24, 5′-TACCCTTGATCAAAGCAGTGTGACGGTAGC-3′; 25, 5′-GCTACCGTCACACTGCTTTGATCAAG-3′; 26, 5′-GACCCTTGATCA- AAGCAGTATGATGGTAGC-3′; 27, 5′-GCTACCATCATACTGCTTTGATCAAG-3′; 28, 5′-TTCTGTCTCCCTCAACCATCACAGGGGTGC-3′; 29, 5′-TTGCACCCCTGTGATGGTTGAGGGAGACAG-3′; 30, 5′-TTGCACCCCTGTCTTGGTTGAGGGAGACAG-3′.

Results

Isolation of mouse RAG-2 genomic DNA clones and characterization of its 5′ flanking region

Mouse genomic clones mRAG-2-4 and mRAG-2-6, which contain the total DNA region of the published mouse RAG-2 cDNA,1 were isolated by screening a mouse genomic DNA library. Restriction enzyme mapping, Southern blot hybridization, DNA sequencing analysis of these clones, and Southern blot hybridization analysis of mouse genomic DNA revealed that the mouse RAG-2 genome consists of 3 exons (data not shown).

To determine the transcription start site of the mouse RAG-2 genome, 5′ RACE was performed using mouse thymocyte poly-A+ RNA. We sequenced 16 clones that contain anticipated restriction enzyme sites. As shown in Figure1, transcription initiated primarily from 2 adjacent nucleotides. No TATA box is present at the 5′ upstream region of the mouse RAG-2 genome. At the major transcription initiation site, there is a sequence (CTCACTGG) similar to an initiator sequence (CTCANTCT), which directs the initiation site of transcription.28 Comparison of nucleotide sequences around the transcription initiation site of the mouse and the human RAG-2 genome (Figure 1B) revealed that the promoter region is conserved between mice and humans. The reported transcription initiation site of the human RAG-2 genome is about 30 bp downstream from that of the mouse RAG-2 genome.29

Characterization of the mouse RAG-2 promoter region.

(A) Mapping of the transcription initiation site of mouse RAG-2by 5′ RACE. The darkened circle denotes the transcription initiation sites of independent cDNA clones characterized by DNA sequence analysis. The major transcription initiation site (+1) and the first exon (boxed) are noted. An arrow indicates the 5′ end of the reported mouse RAG-2 cDNA.1 (B) Alignment of the mouse RAG-2 promoter region with that of the human RAG-2 promoter region. The major transcription initiation site (+1) is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes the identical nucleotide (indicated by a capital letter). Some spaces (dotted lines) are inserted to produce maximal matching. Initiator sequence-like sequence is underlined. Boxed sequences indicate the −80/−17 fragment used as a probe for EMSA in Figures 4 and 5.

Characterization of the mouse RAG-2 promoter region.

(A) Mapping of the transcription initiation site of mouse RAG-2by 5′ RACE. The darkened circle denotes the transcription initiation sites of independent cDNA clones characterized by DNA sequence analysis. The major transcription initiation site (+1) and the first exon (boxed) are noted. An arrow indicates the 5′ end of the reported mouse RAG-2 cDNA.1 (B) Alignment of the mouse RAG-2 promoter region with that of the human RAG-2 promoter region. The major transcription initiation site (+1) is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes the identical nucleotide (indicated by a capital letter). Some spaces (dotted lines) are inserted to produce maximal matching. Initiator sequence-like sequence is underlined. Boxed sequences indicate the −80/−17 fragment used as a probe for EMSA in Figures 4 and 5.

Lymphoid-specific promoter activity in mouse RAG-25′ flanking region

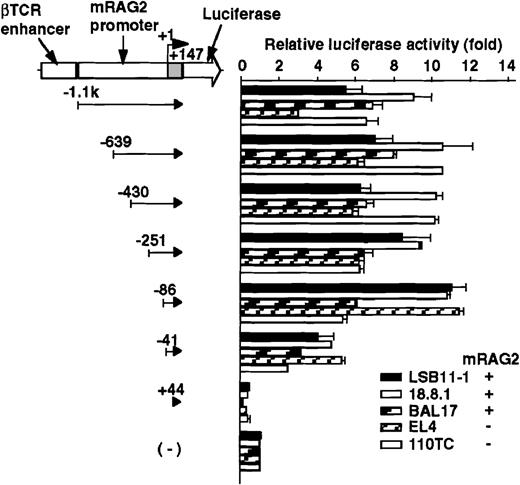

The promoter activity of the 5′ flanking region of the mouseRAG-2 gene was examined by a transient expression assay using luciferase reporter gene constructs (Figures 2 and 3). Because the luciferase activity of the mouse RAG-2 promoter constructs was too weak to be detected, we inserted the βTCR enhancer or SV40 enhancer to augment the transcriptional activity (data not shown). Luciferase constructs containing −1.1 kb to +147 nt genomic DNA fragment and its truncated fragments with the βTCR enhancer were transfected intoRAG-2–expressing lymphoid cell lines (LSB11-1, 18.8.1, or BAL17) and RAG-2–nonexpressing lymphoid cell lines (EL4 or 110TC), and relative luciferase activity was determined. As shown in Figure 2, a fragment containing −1.1 kb to +147 nt exhibited a significant promoter activity not only inRAG-2–expressing lymphoid cell lines but also inRAG-2–nonexpressing lymphoid cell lines. Successive deletion of 5′ flanking region from −1.1 kb to −86 nt did not affect the promoter activity. A significant decrease in the RAG-2 promoter activity was seen when sequences between −86 and −41 nt were deleted. The promoter activity was completely lost by the deletion of sequences between −41 and +44 nt.

Promoter activity of the 5′ flanking region of the mouse RAG-2 in lymphoid cells.

Schematic diagram of luciferase reporter constructs fused to RAG-2 promoter sequences is shown on the left, and the promoter activity in various lymphoid cells is on the right. For the luciferase reporter constructs and the pSRα-LacZ reference plasmids, 5 μg of each were transfected into 5 × 106 mouse lymphoid cell lines (see “Materials and methods”), and their activities were assessed 22-24 hours later. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity, and luciferase construct without a promoter fragment was given a reference value of 1. Error bars indicate deviation of 3-4 experiments.

Promoter activity of the 5′ flanking region of the mouse RAG-2 in lymphoid cells.

Schematic diagram of luciferase reporter constructs fused to RAG-2 promoter sequences is shown on the left, and the promoter activity in various lymphoid cells is on the right. For the luciferase reporter constructs and the pSRα-LacZ reference plasmids, 5 μg of each were transfected into 5 × 106 mouse lymphoid cell lines (see “Materials and methods”), and their activities were assessed 22-24 hours later. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity, and luciferase construct without a promoter fragment was given a reference value of 1. Error bars indicate deviation of 3-4 experiments.

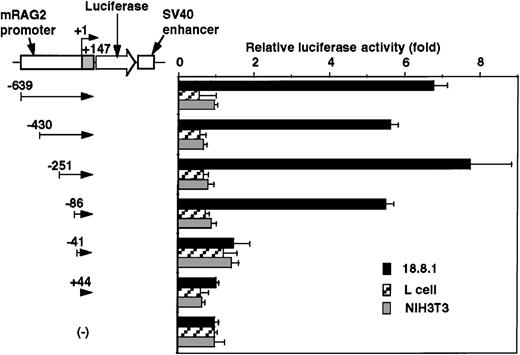

To determine the cell specificity of the promoter region, luciferase constructs containing −639/+147 nt genomic DNA fragment and its truncated fragments with SV40 enhancer were transfected into a lymphoid cell line (18.8.1) and nonlymphoid cell lines (L and NIH3T3), and the relative promoter activity was assessed. As shown in Figure3, the promoter activity was detected in the 18.8.1 cell line but not in either the L or NIH3T3 cell lines. The promoter activity was drastically reduced when DNA fragments were truncated from −86 to −41 nt in 18.8.1 cells. These results indicate the presence of the positive lymphoid-specific regulatory element(s) between the −86 and +44 nt region.

Promoter activity of the 5′ flanking region of mouse RAG-2 in nonlymphoid cells.

Schematic diagram of luciferase reporter constructs fused to RAG-2 promoter sequences is shown on the left, and promoter activity in lymphoid 18.8.1 or nonlymphoid cells (L and NIH3T3) is on the right. Promoter activities were analyzed as in Figure 2. Error bars indicate deviation of 3 experiments.

Promoter activity of the 5′ flanking region of mouse RAG-2 in nonlymphoid cells.

Schematic diagram of luciferase reporter constructs fused to RAG-2 promoter sequences is shown on the left, and promoter activity in lymphoid 18.8.1 or nonlymphoid cells (L and NIH3T3) is on the right. Promoter activities were analyzed as in Figure 2. Error bars indicate deviation of 3 experiments.

Mouse RAG-2 promoter binding protein expressed in B-cell lineage

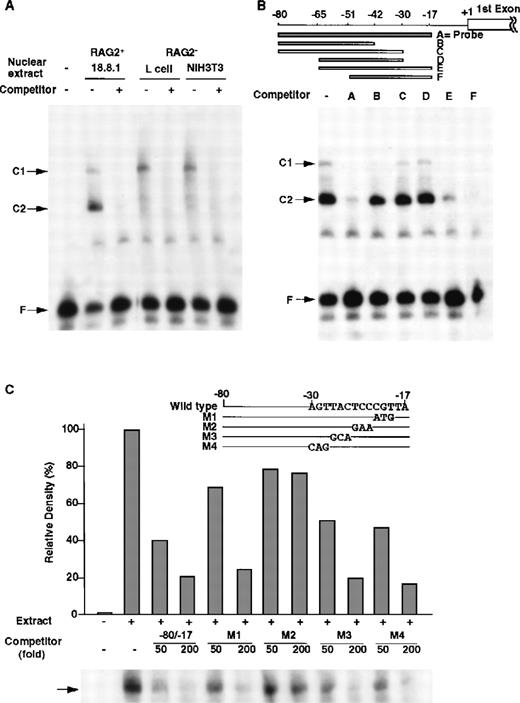

Between −86 nt and +1 (a transcription initiation site), the −80/−17 nt region was well conserved between the mouse and human RAG-2 5′ upstream region (Figure 1B), and this region exhibited the full promoter activity (data not shown). Thus, DNA binding proteins to the −80/−17 promoter region were searched by EMSA (Figure 4). By using the −80/−17 DNA fragment as a probe, only 2 major DNA/protein complexes were detected in the nuclear extract prepared from the 18.8.1 cells (Figure 4A, C1 and C2 complexes). The unlabeled −80/−17 fragment completely inhibited the formation of the C1 and C2 complexes, which indicated that some nuclear proteins specifically bound to the fragment to form the C1 and C2 complexes. The C1 complex was detected not only in the nuclear extract of 18.8.1 pre–B cells but also in the NIH3T3 or L fibroblast cells. In contrast, the C2 complex was detected only in the nuclear extract of the 18.8.1 cells (Figure 4A).

DNA binding proteins that bind to the −80/−17 nt region of the RAG-2 promoter in B-lineage cells.

(A) Nuclear proteins binding to RAG-2 promoter. EMSA was performed as described in “Materials and methods” by incubating nuclear extracts prepared from 18.8.1 cells, L cells, or NIH3T3 cells and the32P-labeled probe DNA (the −80/−17 nt region of the RAG-2 promoter in Figure 1B) in the absence or presence of 100-fold the excess amount of cold probe DNA. C1 and C2 indicate complexes of nuclear protein and probe DNA, and F indicates free probe DNA. (B) Analysis of the R2BP binding region. EMSA was performed using nuclear extracts prepared from 18.8.1 cells and the32P-labeled probe DNA as mentioned above in the presence of various competitor DNA (A-F), as depicted on the top. (C) Mutation analysis of the binding region of R2BP. The RAG-2 promoter fragment (−80/−17 nt region) containing altered nucleotides was prepared (M1-M4, shown on the top). EMSA was performed as in panel B in the presence of 50-fold and 200-fold molar excess of the wild type −80/−17 fragment and the M1, M2, M3, or M4 fragment. Histograms indicate the relative density of the C2 complex shown on the bottom. The density of the C2 complex, in the absence of a competitor, is denoted as 100%.

DNA binding proteins that bind to the −80/−17 nt region of the RAG-2 promoter in B-lineage cells.

(A) Nuclear proteins binding to RAG-2 promoter. EMSA was performed as described in “Materials and methods” by incubating nuclear extracts prepared from 18.8.1 cells, L cells, or NIH3T3 cells and the32P-labeled probe DNA (the −80/−17 nt region of the RAG-2 promoter in Figure 1B) in the absence or presence of 100-fold the excess amount of cold probe DNA. C1 and C2 indicate complexes of nuclear protein and probe DNA, and F indicates free probe DNA. (B) Analysis of the R2BP binding region. EMSA was performed using nuclear extracts prepared from 18.8.1 cells and the32P-labeled probe DNA as mentioned above in the presence of various competitor DNA (A-F), as depicted on the top. (C) Mutation analysis of the binding region of R2BP. The RAG-2 promoter fragment (−80/−17 nt region) containing altered nucleotides was prepared (M1-M4, shown on the top). EMSA was performed as in panel B in the presence of 50-fold and 200-fold molar excess of the wild type −80/−17 fragment and the M1, M2, M3, or M4 fragment. Histograms indicate the relative density of the C2 complex shown on the bottom. The density of the C2 complex, in the absence of a competitor, is denoted as 100%.

To determine the specificity of the expression of these DNA binding proteins, nuclear extracts from various cell lines were prepared and analyzed by EMSA. As shown in Table 1, the nuclear protein forming C2 complex was found in the extracts of all B-lineage cells but not in those of the other lineage cells including the T-lineage cells. The C1 complex was detected in extracts of all cell lines investigated (data not shown). We referred the protein forming C2 complex as the RAG-2 promoter binding protein (R2BP).

To determine the binding region of R2BP, a series of RAG-2 promoter deletions were prepared and used as competitors for EMSA (Figure 4B). DNA fragments of −80/−17, −65/−17, or −51/−17 interfered in the formation of the C2 complex, while DNA fragments lacking the −30 to −17 nt region (−80/−42, −80/−30, or −65/−30) could not inhibit the formation of the C2 complex, which shows that the −30 to −17 nt region was indispensable for the binding of R2BP. To identify the nucleotides responsible for the binding of R2BP, the −80/−17 DNA fragments with serial nucleotide alterations between −30 and −17 nt (M1, M2, M3, or M4) were generated, and their ability to inhibit the formation of the C2 complex in EMSA was investigated. As shown in Figure 4C, the wild type −80/−17 fragment and either the M1, M3, or M4 fragment completely inhibited the C2 complex formation, whereas the M2 fragment failed to inhibit the C2 complex formation. The results clearly show that the altered nucleotides in the M2 fragment are critical for the binding of R2BP.

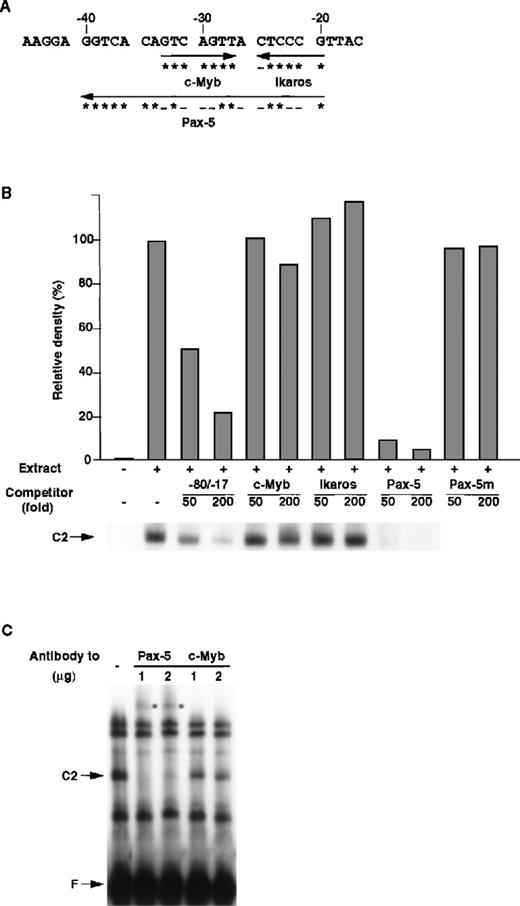

Figure 5A shows the putative transcription factors that bind between the −40 and −17 nt region of the mouse RAG-2 promoter. To clarify which transcription factor(s) is responsible for the formation of the C2 complex, consensus binding sequences of c-Myb, Ikaros, and Pax-5 were generated, and their ability to inhibit the formation of the C2 complex was tested. As shown in Figure 5B, c-Myb binding and Ikaros binding sequences did not inhibit the binding of R2BP, whereas Pax-5 binding sequences completely inhibited the binding of R2BP to the −80/−17 DNA fragment. The mutant Pax-5 binding DNA sequence, to which Pax-5 cannot bind,27 did not inhibit the binding of R2BP. Furthermore, anti–Pax-5 antibody, but not anti–c-Myb antibody, caused a supershift of the C2 complex (Figure 5C). These results show that R2BP corresponds to Pax-5.

Identification of R2BP as a Pax-5.

(A) Putative binding sites of transcription factors in the RAG-2 promoter. The asterisk denotes a nucleotide identical with consensus binding sequences (c-Myb, 5′-GNCNGTT-3′; Ikaros, 5′-T/CGGGAA/T-3′; Pax-5, 5′-CTTGA/GTCAAA/TGCAGT/CGT/GG/AACG/CG/ATAGC-3′27), and the minus sign shows a nucleotide nonidentical with consensus binding sequences. (B) Competition of R2BP binding with the consensus sequence of Pax-5. EMSA was performed as in Figure 4 using nuclear extract prepared from 18.8.1 cells and the −80/−17 nt RAG-2 promoter region as a probe. The consensus binding sequence for the c-Myb, Ikaros, Pax-5, or Pax-5 binding sequence mutant (Pax-5m) was used as a competitor. Histograms indicate the relative density of the C2 complex shown on the bottom. The density of the C2 complex in the absence of the competitor is denoted as 100%. (C) The effect of anti–Pax-5 antibody on EMSA. EMSA was performed as described above in the absence or the presence of anti–Pax-5 or anti–c-Myb antibody. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–Pax-5 antibody.

Identification of R2BP as a Pax-5.

(A) Putative binding sites of transcription factors in the RAG-2 promoter. The asterisk denotes a nucleotide identical with consensus binding sequences (c-Myb, 5′-GNCNGTT-3′; Ikaros, 5′-T/CGGGAA/T-3′; Pax-5, 5′-CTTGA/GTCAAA/TGCAGT/CGT/GG/AACG/CG/ATAGC-3′27), and the minus sign shows a nucleotide nonidentical with consensus binding sequences. (B) Competition of R2BP binding with the consensus sequence of Pax-5. EMSA was performed as in Figure 4 using nuclear extract prepared from 18.8.1 cells and the −80/−17 nt RAG-2 promoter region as a probe. The consensus binding sequence for the c-Myb, Ikaros, Pax-5, or Pax-5 binding sequence mutant (Pax-5m) was used as a competitor. Histograms indicate the relative density of the C2 complex shown on the bottom. The density of the C2 complex in the absence of the competitor is denoted as 100%. (C) The effect of anti–Pax-5 antibody on EMSA. EMSA was performed as described above in the absence or the presence of anti–Pax-5 or anti–c-Myb antibody. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–Pax-5 antibody.

Mouse RAG-2 promoter binding protein expressed in T-cell lineage

Using the −80/−17 RAG-2 promoter fragment, we could not detect any DNA binding protein specifically expressed in the T-cell lineage. Search for putative binding sites of transcription factors revealed that a potential GATA binding sequence (CATC) exists in the −80/−66 sequence (Figure 6A), which is conserved between mice and humans (Figure 1B). Thus, we prepared a DNA fragment containing a tandem repeat of the GATA binding sequence (Figure 6, legend) and performed EMSA. As shown in Figure 6B, the C3 and C4 complexes were formed by proteins in the EL4 extract, and these complexes were inhibited by the GATA binding sequence as well as the −85/−56 sequence. Inhibition by the −85/−56 fragment was specific because the −51/−17 fragment did not inhibit the formation of the C3 and C4 complexes (data not shown).

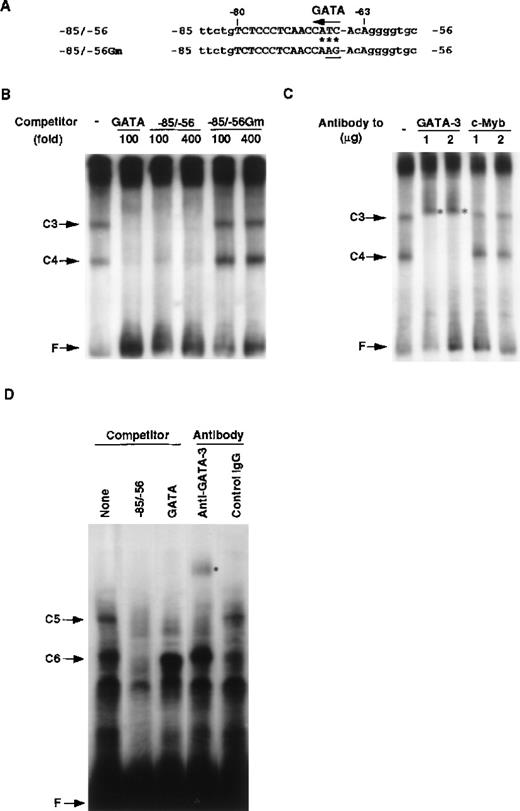

Identification of T-cell–specific binding protein as GATA-3.

(A) Putative binding site for the GATA family in the RAG-2 promoter. Possible GATA binding site present in the −85/−56 RAG-2 promoter region is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes a nucleotide identical with the consensus GATA family binding sequences 5′-TATC-3′. The TC in the putative GATA binding site was altered to AG (underlined) in the −85/−56 Gm. (B) Nuclear proteins binding to the RAG-2 promoter in T cells. EMSA was performed by incubating nuclear extract prepared from EL4 cells and the32P-labeled probe containing GATA binding sites (5′-AAGCTTGATGCT- CTAGATAACGGGAGTAGCTCTAGATAACGGGGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCCGT- TATCTAGAGCGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCCGTTAGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCC- GTTATCTAGAGCATCGAATTC-3′) in the presence of 4 mmol/L magnesium chloride (MgCl2). C3 or C4 indicates a nuclear protein complex with probe DNA, and F indicates a free probe DNA. As a competitor, we used 100-fold or 400-fold molar excess of consensus binding sequences for GATA, the −85/−56 fragment, or the −85/−56 Gm. (C) The effect of anti–GATA-3 antibody on EMSA. EMSA was performed as described above in the presence of anti–GATA-3 or anti–c-Myb antibody. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–GATA-3 antibody. (D) Binding of GATA-3 to the −85/−56 region. EMSA was performed by incubating nuclear extracts prepared from 293T cell transfectants of GATA-3 and the 32P-labeled −85/−56 fragment. C5 or C6 indicates a complex of a nuclear protein and probe DNA, and F indicates a free probe DNA. A 200-fold molar excess of the −85/−56 fragment and consensus binding sequences for GATA were used as competitors. We used 0.5 μg anti–GATA-3 antibody or control mouse IgG for the supershift analysis. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–GATA-3 antibody.

Identification of T-cell–specific binding protein as GATA-3.

(A) Putative binding site for the GATA family in the RAG-2 promoter. Possible GATA binding site present in the −85/−56 RAG-2 promoter region is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes a nucleotide identical with the consensus GATA family binding sequences 5′-TATC-3′. The TC in the putative GATA binding site was altered to AG (underlined) in the −85/−56 Gm. (B) Nuclear proteins binding to the RAG-2 promoter in T cells. EMSA was performed by incubating nuclear extract prepared from EL4 cells and the32P-labeled probe containing GATA binding sites (5′-AAGCTTGATGCT- CTAGATAACGGGAGTAGCTCTAGATAACGGGGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCCGT- TATCTAGAGCGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCCGTTAGTCACAGTCAGTTACTCCC- GTTATCTAGAGCATCGAATTC-3′) in the presence of 4 mmol/L magnesium chloride (MgCl2). C3 or C4 indicates a nuclear protein complex with probe DNA, and F indicates a free probe DNA. As a competitor, we used 100-fold or 400-fold molar excess of consensus binding sequences for GATA, the −85/−56 fragment, or the −85/−56 Gm. (C) The effect of anti–GATA-3 antibody on EMSA. EMSA was performed as described above in the presence of anti–GATA-3 or anti–c-Myb antibody. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–GATA-3 antibody. (D) Binding of GATA-3 to the −85/−56 region. EMSA was performed by incubating nuclear extracts prepared from 293T cell transfectants of GATA-3 and the 32P-labeled −85/−56 fragment. C5 or C6 indicates a complex of a nuclear protein and probe DNA, and F indicates a free probe DNA. A 200-fold molar excess of the −85/−56 fragment and consensus binding sequences for GATA were used as competitors. We used 0.5 μg anti–GATA-3 antibody or control mouse IgG for the supershift analysis. The asterisk denotes the band shifted with the anti–GATA-3 antibody.

At the top of the gel, a high molecular weight complex was observed, but the complex was not competed by the −85/−56 fragment, indicating that the DNA binding protein(s) forming this complex does not bind to the −85/−56 promoter region. The −85/−56 fragment with a mutation for the putative GATA binding sequence (Figure 6A) did not inhibit the C3 and C4 complex formation. The C3 and C4 complexes were detected in the nuclear extracts from other T cell lines, but they were not detected in those from B cell lines or nonlymphoid cell lines (Table2). These results indicate that a GATA binding protein may be responsible for the formation of the C3 and C4 complexes and that it binds to a possible GATA binding site located at the −68/−66 fragment of the mouse RAG-2 promoter. The C3 complex may correspond to the complex with 2 GATA proteins, and the C4 complex may correspond to one with a single GATA protein. Because GATA-3 is a T-cell–specific GATA family, we examined whether or not GATA-3 bound to the RAG-2 promoter. As shown in Figure 6C, anti–GATA-3 antibody, but not anti–c-Myb antibody, caused the supershift of the C3 and C4 complexes.

To further confirm the binding of GATA-3 to the −85/−56 fragment, we used the −85/−56 fragment as a probe and performed EMSA. Nuclear extracts containing recombinant GATA-3 were prepared from 293T cell transfectants and used for EMSA. As shown in Figure 6D, 2 protein/DNA complexes, C5 and C6, were formed, and the formation of these complexes were inhibited by the unlabeled −85/−56 fragment. In those complexes, only the C5 complex was specifically competed out by the consensus GATA binding sequence and supershifted by the binding of the anti–GATA-3 antibody. These results confirmed that GATA-3 binds to the −85/−56 mouse RAG-2 promoter fragment and forms the C5 complex. When EMSA was performed using the DNA fragment containing the tandem repeat of the GATA binding sequence and the nuclear extracts containing recombinant GATA-3, the signal of the GATA-3 complex was more than 100-fold stronger than that formed with the −85/−56 fragment. Furthermore, when EMSA was performed using the nuclear extracts prepared from EL4 cells and the −85/−56 fragment as a probe, GATA-3 binding was not observed (data not shown). Taken together, although the affinity of GATA-3 to the −85/−56 fragment was not high, GATA-3 in T-cell nuclear extracts bound to the mouse RAG-2 promoter region.

Possible involvement of Pax-5 or GATA-3 in RAG-2 promoter activity in B or T cells

To examine whether Pax-5 or GATA-3 is involved in mouse RAG-2 promoter activity, luciferase constructs with the −86/+147 mouse RAG-2 promoter fragment containing the mutation for a Pax-5 binding site (M2) (Figure 4C) or for a GATA binding site (Gm) (Figure 6A) were transfected into a pre–B cell line, 18.8.1 cells, or an immature T cell line, LSB11-1, and the relative luciferase activity was measured. As shown in Figure 7, the M2 binding site exhibited a decreased promoter activity in the 18.8.1 cells but not in the LSB11-1 cells. Contrary to this, the Gm showed significantly decreased promoter activity in the LSB-11 cells but not in the 18.8.1 cells. The result suggests that Pax-5 is involved in activation of the RAG-2 promoter in B-lineage cells, and GATA-3 is involved in the activation of the RAG-2 promoter in T-lineage cells.

Possible involvement of Pax-5 and GATA-3 in mouse RAG-2 promoter activity.

Luciferase constructs were transfected together with pSRα-LacZ reference plasmids into 5 × 106 B-lineage cells (18.8.1) or T-lineage cells (LSB11-1) and analyzed for activity as shown in Figure 2. Four luciferase constructs were used: without a promoter, with the wild type −86/+147 RAG-2 promoter (WT), or with the promoter containing a nucleotide alteration in either the Pax-5 binding site (M2) (Figure 4C) or GATA binding site (Gm) (Figure6A). Representative data of 3 independent experiments are shown.

Possible involvement of Pax-5 and GATA-3 in mouse RAG-2 promoter activity.

Luciferase constructs were transfected together with pSRα-LacZ reference plasmids into 5 × 106 B-lineage cells (18.8.1) or T-lineage cells (LSB11-1) and analyzed for activity as shown in Figure 2. Four luciferase constructs were used: without a promoter, with the wild type −86/+147 RAG-2 promoter (WT), or with the promoter containing a nucleotide alteration in either the Pax-5 binding site (M2) (Figure 4C) or GATA binding site (Gm) (Figure6A). Representative data of 3 independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

To understand the regulatory mechanism of the RAG gene expression, we cloned the mouse RAG-2 genomic genes, determined its transcription initiation site as well as the core promoter region, and demonstrated the involvement of separate transcription factors in the regulation of RAG-2 promoter activity in B- and T-lineage cells. The transcription initiation site of mouse RAG-2, approximately 30 bp upstream from that of human RAG-2, was determined by 5′ RACE (Figure 1). We found that the 5′ flanking regions of both mouse and human RAG-2 were highly conserved, indicating that the fundamental transcriptional regulation of RAG-2 may be conserved between mice and humans. As demonstrated in the 5′ flanking region of human RAG-1 andRAG-2,17,18,29 no canonical TATA box is located within anticipated distances from the transcription initiation site of mouse RAG-2. However, a sequence (CTCACTGG) similar to an initiator sequence (consensus, CTCANTCT) was found at the major transcription initiation site. An initiator-like sequence (CTCTCTTT) is also located at the transcription initiation site of human RAG-2, as described by Zarrin et al.29 An initiator sequence directs the initiation site of transcription in some TATA-less promoter, such as the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase gene,28 and may play a role in localizing the transcriptional machinery to the RAG-2 promoter.

The 5′ flanking region of the mouse RAG-2conferred a significant level of luciferase activity when transfected into RAG-2–expressing as well as RAG-2–nonexpressing lymphoid cell lines (Figure 2). However, its promoter region did not exhibit the luciferase activity when transfected into nonlymphoid cell lines (Figure 3). This clearly indicates that the minimal promoter region of the mouse RAG-2 contains a cis-element that confers lymphoid-specific expression of RAG-2. It also indicates that the differentiation stage-specific expression of RAG-2 may be regulated by other mechanisms such as the enhancer or suppresser cis-element or alteration of the chromatin structure. Concerning the chromatin structure, we20 and Fuller et al19demonstrated the appearance of DNase I hypersensitive sites surrounding mouse or human RAG-1, which is located adjacent toRAG-2 and expressed in concert with RAG-2, and that their appearance accompanies lymphocyte development and RAG-1expression.

To search the transcriptional factors regulating the lymphoid-specific RAG-2 promoter activity, EMSA was performed with the core RAG-2 promoter fragment. We demonstrated that Pax-5 binds to the core promoter region in B-lineage cells and that GATA-3 binds to the region in the T-lineage cells (Figures 4-6). So far, there has been no identification of common lymphoid-specific factors that bind to the core RAG-2 promoter region. Furthermore, the alteration of nucleotides that abolished the binding of Pax-5 resulted in a decrease of the promoter activity in a B cell line but not in a T cell line. In contrast, the change of nucleotides that abolished the binding of GATA-3 exhibited a decrease of the promoter activity in a T cell line but not in a B cell line (Figure 7). The results indicate that these sites are important for the RAG-2 promoter activity when analyzed by luciferase reporter gene assay. It should be necessary to demonstrate the binding of Pax-5 or GATA-3 to these sites in situ in order to prove the physiological importance of these transcription factors in RAG-2 promoter activity.

It is noted that mutations in both Pax-5 binding and GATA-3 binding sites did not reduce the promoter activity to the background level, which indicates that other factor(s) may also be involved in the RAG-2 promoter activity. It is also noted that alteration of the Pax-5 binding site of the promoter region caused a significant enhancement of the promoter activity in a T cell line (Figure 7B). The data pose a possibility that repressing factor(s) bind to the Pax-5 binding site in T-lineage cells. In this respect, Figure 4 indicates the presence of an additional factor(s) other than Pax-5 or GATA-3 that binds to the −80/−17 mouse RAG-2 promoter region. The DNA binding protein forming the C1 complex existed in the extracts prepared from all cell lineages, and the complex formation was inhibited by the fragments −65/−17 and −51/−17, which demonstrates that the protein binding site may overlap with that of Pax-5. The database search revealed putative transcription factor binding sites in the −51/−17 fragment including the binding sites for CF-1, which interact with the c-myc and actin promoter as well as the immunoglobulin enhancer30; CREB, a cyclic adenosine monophosphate CcAMP response element binding protein31; and AP-1, a fos/jun complex.32 These factors are ubiquitously expressed and could repress the mouse RAG-2 promoter activity in T cells. This is merely a speculation and should be investigated at the molecular level.

Pax-5 is specifically expressed in B cells in lymphoid organs.33 It has been shown that B-cell differentiation was completely blocked at an early precursor stage in mice lacking Pax-5, although T-cell differentiation was not affected.34 On the contrary, GATA-3 was specifically expressed in T-lineage cells,35 and GATA-3−/−ES cells failed to differentiate into T-lineage cells.36 Recently it has also been indicated that GATA-3 is involved in Th2 cell development from the Th0 precursor cells.37 In this study we showed that these key transcription factors, which are involved in the commitment of either B or T lineage, play an important role in the promoter activity of mouse RAG-2. Concerning transcription factors regulating lymphocyte development, PU.1 and Ikaros are expressed in pluripotent stem cells, lymphoid progenitors, and immature or mature lymphocytes.38 During the commitment to lymphocytes, E2A, early B cell factor (EBF), and Pax-5 are expressed in B-lineage cells, and GATA-3 is expressed in T-lineage cells, which indicates that commitment to lymphocytes is regulated by different factors rather than common factors in B- and T-lineage cells.

Recently, Nutt et al39 showed that Pax-5–deficient pro-B cells, which had been expanded on stroma cells in the presence of interleukin-7 (IL-7), expressed RAG-1 and RAG-2, and the data indicated that Pax-5 is not necessarily required forRAG expression. However, it should be noted that the data also demonstrated that B-lymphoid progenitor cells could never be detected in Pax-5–deficient fetal liver, which strongly suggests that the function of Pax-5 can be compensated for by the other factors derived from stroma cells and/or IL-7. As described above, E2A and EBF are potential transcription factors during early B-cell development. However, no putative binding sites for these factors were present up to 86 nt in the mouse RAG-2 promoter region. It should be clarified whether such B-cell–specific transcription factors bind to a cis-element in the other region to regulate RAG-2 expression or whether other novel transcription factors are induced by signals from bone marrow stroma cells and IL-7.

During the preparation of our manuscript, a report40indicating the involvement of Pax-5 in the regulation of the RAG-2 promoter in B cells was published. Lauring and Schlissel40have characterized the promoter of the mouse RAG-2 gene and determined the transcription initiation site. When compared to the data in the present study, the transcription start site they determined was 29 nt downstream. They have also shown that deletion of the RAG-2 promoter region to −42 nt still possesses a full promoter activity in B-lineage cells. The authors concluded that the 3′ downstream region from the −42 nt was essential for the promoter activity in B-lineage cells. However, in this study we demonstrated that deletion of the RAG-2 promoter sequences to −86 nt showed a full promoter activity, but its deletion to −41 nt resulted in a decrease, by half, of the promoter activity in B-lineage cells (Figure2). This indicates that the −86/−42 fragment is also involved in the RAG-2 promoter activity in B-lineage cells. In the case of T-lineage cells, they indicated that the −127/−78 region was indispensable for the promoter activity. However, we have shown here that the deletion to −86 nt still exhibited the full promoter activity in T-lineage cells, and we finally found that GATA-3 was bound to the −80/−56 region with a core sequence of 5′-ATC-3′ at −68 nt. Our data show that the −80/−42 region plays an important role in T-cell–specific regulation of the RAG-2 promoter activity. These contradictions between our data and theirs may be derived from the differences of reporter genes used. With this regard, we used luciferase reporter constructs with βTCR enhancer to augment the transcriptional promoter activity of RAG-2 in this study.

Analysis of the mouse RAG-2 promoter has provided insight into the basis of constitutive expression of RAG-2 in lymphocytes. Our study shows that the 5′ flanking region of mouse RAG-2contains the promoter that confers lymphocyte-specific expression ofRAG-2 and that distinct DNA binding proteins may separately regulate RAG-2 expression in B- and T-lineage cells. Lauring and Schlissel40 have demonstrated that Pax-5 binds to the RAG-2 promoter in vivo by in vivo footprint analysis. To demonstrate the role of GATA-3 in RAG-2 promoter activity in vivo, we should further analyze the binding of GATA-3 to the promoter region in T cells by in vivo footprint analysis as well as the effect of dominant negative GATA-3 on RAG-2 expression in T cells. It should also be noted that factors which confer the regulatory mechanisms for transcriptional activation as well as inactivation of the RAG-2gene during lymphocyte development remain to be clarified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr K. Sakaguchi for providing 18.8.1, WEHI279, and BAL17 cell lines; Dr H. Kikutani for donating M1 and WEHI3 cell lines; and Dr M. Yamamoto for the generous gift of GATA-3 cDNA.

Supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan (11470169), Tokyo, Japan.

Reprints:Atsushi Muraguchi, Department of Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical University, 2630 Sugitani, Toyama, 930-0194 Japan; e-mail:gucci@ms.toyama-mpu.ac.jp.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.