To evaluate the efficacy of a combined modality treatment (MACOP-B plus mediastinal radiotherapy) and the advantages of Gallium-67-citrate single-photon emission (67GaSPECT) over computed tomography (CT) for restaging in patients with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) with sclerosis. Between 1989 and 1998, 50 previously untreated patients with PMLBCL with sclerosis (70% with bulky mass) were treated with MACOP-B regimen plus mediastinal radiotherapy. The radiologic clinical stage with evaluation of tumor size included CT and 67GaSPECT at diagnosis, after chemotherapy, and after radiotherapy. Forty-three patients (86%) achieved a complete response and 7 were nonresponders to treatment. For the imaging evaluation, only 47 patients were evaluable because 3 had disease progression during chemotherapy. After treatment, 3/5 (60%) patients with positive 67GaSPECT and negative CT scan relapsed, as against 0/21 (0%) with negative 67GaSPECT and CT scan. Twenty-one patients had a positive CT scan: of these, the 4 with positive 67GaSPECT all progressed, whereas there were no relapses among the 17 with negative 67GaSPECT. After radiotherapy, there was a decrease of positive CT (from 33 to 21 cases) and of positive 67GaSPECT (from 31 to 9 cases). Relapse-free survival rate was 93% at 96 months (median 39 months). In patients with PMLBCL with sclerosis, MACOP-B plus radiation therapy is a very useful first-line treatment and radiation therapy may play an important role. As regards restaging, 67GaSPECT should be considered the imaging technique of choice at least in patients who show CT positivity.

PRIMARY MEDIASTINAL large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) with sclerosis is now considered to be a particular clinical and pathological entity and has been included in the R.E.A.L. classification1 among the aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. It has a characteristic morphologic and immunophenotypic picture2-5 showing a diffuse proliferation of large cells with clear cytoplasm and the presence of variable degrees of sclerosis that causes its typical compartmentalization pattern. PMLBCL with sclerosis also presents with characteristic clinical features that are almost specific, and with predominant or exclusive mediastinal involvement. Women outnumber men by two to one, and the median age is less than 30 years. The patients show a bulky mediastinal mass often invading adjacent organs and structures (lung, superior vena cava, pleura, pericardium, and the chest wall) producing typical symptoms of cough, chest pain, and dyspnea.6-9 Bulky mediastinal disease is observed in more than 60% to 70% of the patients and intrathoracic extension to adjacent organs is present in about 50% of patients. Only 20% of the patients are in stage III-IV at diagnosis and extranodal spread or bone marrow involvement are rare. PMLBCL with sclerosis can at times present with superior venacaval compression or obstruction and, for this reason, requires rapid completion of diagnosis and staging.

Several early reports10-12 described PMLBCL with sclerosis as an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis when the patients were treated with the Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, Vincristine, and Prednisone (CHOP) regimen followed by radiation therapy, whereas others13-16 reported good results using first-generation chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP or CHOP-like. Other reports17-21 have also described good results using other third-generation Methotrexate, Adiramycin, Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Prednisone, and Bleomycin (MACOP-B) or MACOP-B–like regimens and radiotherapy. The use of high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission has been recommended in some reports22,23 but remains unproven. In this study, we report the clinical findings and response to MACOP-B chemotherapy regimen and mediastinal radiotherapy in 50 consecutive patients with PMLBCL with sclerosis enrolled in a prospective trial who underwent computed tomography (CT) and Gallium-67-citrate single-photon emission (67GaSPECT) for routine restaging during and after treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 1989 and 1998 in our Institute and in Department of Hematology, “La Sapienza” University (Rome, Italy), 50 consecutive patients with PMLBCL with sclerosis completed treatment with MACOP-B regimen and mediastinal radiotherapy. Criteria for entry into the study included: histologic diagnosis of PMLBCL with sclerosis according to the R.E.A.L. classification1; stage I with bulky disease and stages II-IV as outlined by the Ann Arbor conference24; no prior therapy. Radiological clinical staging with evaluation of tumor size included total body CT and 67GaSPECT. CT was monitored at diagnosis (before therapy), at the end of chemotherapy, and 3 months after radiotherapy. 67GaSPECT was monitored at the time of diagnosis and at the end of chemotherapy and 3 months after radiotherapy (if conducted earlier 67GaSPECT can provide false positives and, therefore, mislead even experienced clinicians).25 The remaining staging procedures included bone marrow biopsy and hematologic and biochemical survey. The extent of mediastinal disease was defined by a mediastinal mass ratio (MMR), calculated by measuring the maximum intrathoracic diameter; MMR that exceeded one third or a mass measuring ≥10 cm in its largest single diameter, as measured by CT, was considered as bulky.

Patients’ characteristics.

Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 31 years (range, 21 to 55 years); 30 (60%) were females and 20 (40%) males. Forty-two (84%) had stage I-II and 8 (16%) stage III-IV disease. One patient had bone marrow involvement. Systemic B symptoms were present in only 14 (28%) patients. At diagnosis, 17 (34%) patients had clinical features of superior vena cava syndrome whereas 17 (34%) had pleural and 8 (16%) pericardial effusions, respectively. The mediastinal involvement was bulky at presentation in 35 (70%) patients.

Treatment protocol.

All patients were treated with the MACOP-B regimen as previously described by Klimo et al.26 After 4 to 6 weeks from the completion of the chemotherapy program, all patients received radiation therapy to the mediastinum with a tumor dose ranging from 30 to 36 Gy over 4 to 5 weeks on a schedule of 180 cGy/day for 5 days per week; a 6-MV linear accelerator was used. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Evaluation of response.

Complete response was defined as a complete regression of all assessable disease or a response ≥80% of residual mediastinal mass in the size of clinically apparent disease without any evidence of regrowth on completion of induction therapy. The mediastinal mass was always measured in terms of product of the largest two perpendicular diameters. For the purpose of this study, results of67GaSPECT were not considered when assigning response status after therapy. All patients had positive 67GaSPECT at the time of diagnosis and at least one documented67GaSPECT after the completion of combination therapy. Partial response was defined as the reduction of at least 50% of known disease with disappearance of the systemic manifestations. No response was defined as less than 50% reduction of the measurable tumor or progression of the disease. Survival was calculated from the beginning of treatment until death or last follow-up. Relapse-free survival was estimated from the date of documented complete remission (CR) to the last follow-up or relapse. The overall survival and relapse-free survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.27

RESULTS

Three out of 50 (6%) patients showed a disease progression during MACOP-B regimen and, for this reason, these patients were not included on the imaging evaluation with both CT and 67GaSPECT.

The imaging outcome, which provided two possible situations, is summarized in Table 2. Regarding CT scan, 33 of 47 (70%) patients had residual mediastinal tumor masses (≤ 20% of the initial volume) after MACOP-B, and after radiation therapy 21 of 47 (44%) patients presented residual masses at CT. Regarding67GaSPECT, 31/47 (66%) patients showed persistent abnormal uptake after MACOP-B while following radiotherapy setting, only 9 of 47 (19%) patients were still 67GaSPECT positive. At the end of treatment (see Table 3), 38 of 47 patients (81%) were gallium negative and none of these patients relapsed. Nine patients (19%) had persistent gallium-positive disease in the mediastinum; in 5, the CT suggested CR but 3 of these 5 relapsed; in 4, CT scan was also abnormal and all 4 patients had progressive disease. Therefore, our data argue strongly that gallium-scan negativity is an important prognostic factor in restaging patients treated for PMLBCL. It is noteworthy that after radiotherapy, 12 of 33 (36.5%) patients who had a CT residual mediastinal tumor after chemotherapy showed a negative CT. In addition, 22 of 31 (71%) patients with positive 67GaSPECT after MACOP-B obtained a negative 67GaSPECT after radiotherapy.

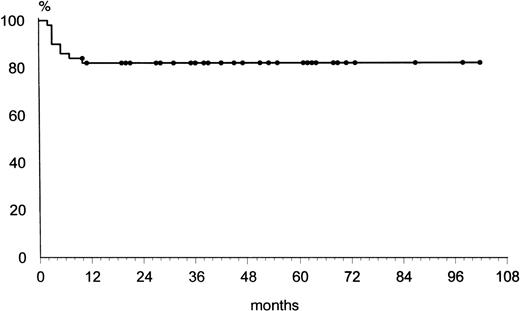

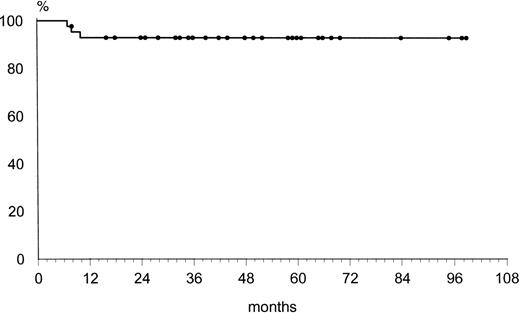

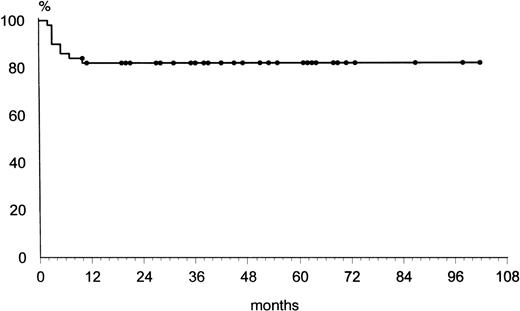

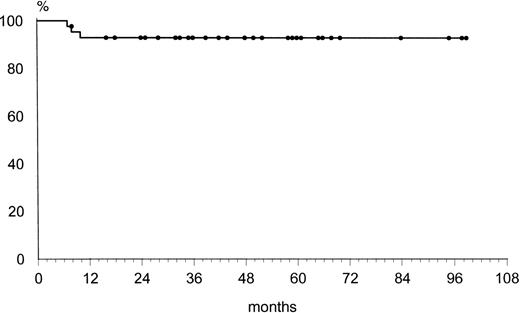

At the time of this analysis, 40 of 43 (93%) CR patients remain in continuous CR with a median follow-up of 39 months (range 7 to 99 months). Three relapses were observed at 7, 8, and 10 months, respectively: the first (mediastinum and lung relapse) subsequently died after 25 months because of disease progression; the second (mediastinum and kidney relapse) died after 8 months because of disease progression in spite of two courses of the Ifosfamide, Epirubicin, and Etoposide (IEV) regimen28 and autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation; the third (mediastinum and breast relapse) achieved a second continuous CR after five courses of the IEV regimen.28 All these 3 patients were CT negative but67GaSPECT positive after the combined first-line treatment. The other 2 patients with the same imaging situation after MACOP-B and radiation therapy are still in continuous CR after 24 and 42 months. No relapses were recorded in any of the other patients who had negative67GaSPECT, independently of CT. As shown in Fig 1, the overall survival was 82% at 96 months. The relapse-free survival curve of the 43 patients who achieved CR showed a plateau at 93% (Fig 2) at 96 months.

Relapse-free survival curve of 43 complete responders after MACOP-B and radiation therapy.

Relapse-free survival curve of 43 complete responders after MACOP-B and radiation therapy.

DISCUSSION

The pathological and clinical characteristics of PMLBCL with sclerosis have been well documented.1-5 The urgency of the initial presentation and its locally aggressive and invasive course justify the idea that this lymphoma should prompt a rapid conclusion of diagnosis and staging procedures. Response to treatment and clinical outcome have varied from one series to another, probably owing to the small number of patients in most series and the heterogeneity of treatment. Early studies suggesting that PMLBCL with sclerosis were unusually aggressive with a poorer prognosis with respect to other large-cell lymphomas10-12 have been contradicted by more recent reports. CR rates of 53% to 80% have been reported after initial therapy with a 50% to 65% overall survival rate at 5 years.13-21 Regarding the use of different chemotherapeutic regimens (CHOP or CHOP-like v third-generation regimens), a recent report by Fisher et al29 showed that results with CHOP are equivalent to results with intensive third-generation regimens, and this may moderate calls for the use of more-aggressive protocols in PMLBCL with sclerosis. Nevertheless, the debate is still open because comparison of the advantages of the two different regimens is difficult, and, there is also the problem of explaining the different CR and survival rates reported from different institutions that use similar treatments, most likely due to patient selection. In addition, the issue of adjuvant radiotherapy after chemotherapy also remains open, although it seems likely that it could play an important role in this locally aggressive disease, particularly in the presence of bulky presentation.

The management of PMLBCL with sclerosis can be complicated by the presence of residual masses of uncertain significance. Few clinical tools are available to help identify patients in apparent CR or partial remission (PR) who have occult residual disease. Incomplete regression of a lymphomatous mass despite apparently effective therapy constitutes a major problem in the treatment of this lymphoma, especially in patients presenting with a bulky mediastinum. In many cases, such residual masses consist of residual fibrotic tissue with no active lymphomatous component, whereas in other cases active residual disease may still be present. This dilemma can occur after combined modality treatment (chemotherapy and radiation therapy). Recently, some reports21,25 30-32 have stressed the potential usefulness of 67GaSPECT scanning to discriminate between active residual tumor and benign fibrous tissue.

To our knowledge the present study is the largest currently available focusing on the real role of first-line MACOP-B regimen in combination with radiation therapy and on the real efficacy of67GaSPECT scanning in the qualitative evaluation of residual mediastinal masses detected by CT in patients with PMLBCL with sclerosis. In our study of 50 consecutive patients the MACOP-B regimen plus mediastinal radiotherapy yielded a CR rate of 86% with only 7 nonresponders and a relapse-free survival of 93% at a median follow-up of 39 months. In the context of this combined therapeutic approach, radiation therapy turned out to be an important adjuvant treatment. Indeed, after its administration there was a decrease of positive CT from 33 to 21 cases and of positive 67GaSPECT from 31 to 9 cases. As expected, CT showed a considerable percentage of residual masses in the mediastinum after MACOP-B and radiation therapy, with a persistent mass constituting ≤20% of the initial disease being present in 45% of our patients.

All four CT+, 67GaSPECT+ patients evidenced disease progression in the 67GaSPECT+sites. This figure strongly contrasts with complete absence of relapses among the 17 CT+, 67GaSPECT−patients. Moreover, it is noteworthy that 3/5 (60%) CT− patients who turned out to be67GaSPECT+ relapsed within 10 months in mediastinal sites in which disease had been present at diagnosis. Finally, further evidence that 67GaSPECT+restaging shows induction failure was supplied by the rapidity with which the positive cases relapsed: 7/9 (78%)67GaSPECT+ patients developed clinical disease within 12 months of completing the combined modality treatment.

These findings lead us to conclude that a sequential weekly treatment of a protocol such as MACOP-B, because of its continuous antineoplastic effect over 3 months, may be considered a very useful first-line therapeutic approach for PMLBCL with sclerosis. Secondly, this study may provide a confirmation of 67GaSPECT’s utility as a specific tool for discriminating fibrotic and tumor tissue and therefore its validity in the restaging of mediastinal masses in these lymphomas after combined modality therapy. This restaging technique allows identification of a subset of patients with residual radiographic abnormalities who need no further therapy (negative67GaSPECT) and of poor prognosis patients who do require further treatment (ie, autologous bone marrow transplantation). Thirdly, radiation therapy may have a pivotal role in this combined modality of treatment. However, given the young age of the patient it is not possible to ascertain whether radiation therapy is required for the patients who became gallium-scan negative with chemotherapy. Further studies are needed to assess the possibility of using67GaSPECT to select those patients who really require the addition of radiation therapy after chemotherapy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Pier Luigi Zinzani, MD, Istituto di Ematologia e Oncologia Medica “Seràgnoli” Policlinico S. Orsola, Via Massarenti 9, 40138 Bologna, Italy.