Abstract

Controversy exists concerning the preferential infection and replication of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) within naive (CD45RA+) and memory (CD45RO+) subsets of CD4+ lymphocytes. To explore the susceptibility of these subsets to HIV-1 infection, we purified CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO) cells from normal donors and subjected them to a novel monokine activation culture scheme. Following HIV-1 infection and interleukin-2 (IL-2) induction, viral production measured on day 13 was 19-fold greater in RO cultures compared with RA cultures. IL-2–stimulated proliferation in uninfected control cultures was equivalent. To explore the mechanisms by which RA cells were reduced in viral production capacity, RA and RO cells were exposed to HIV-1 followed by treatment with trypsin, and then phytohemagglutinin antigen (PHA)-stimulated at days 4, 7, and 10 postinfection. HIV-1 production in day 4 postinfection RA and RO cultures was analogous, indicating that viral fusion and entry had occurred in both cell types. However, whereas similarly treated day 7 and 10 postinfection RO cultures produced virus, HIV-1 was markedly reduced or lost in the corresponding RA cultures. These results suggest that a temporally labile postfusion HIV-1 complex exists in unstimulated RA cells that requires cellular activation signals beyond that provided by IL-2 alone for productive infection.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY virus-1 (HIV-1) selectively infects cells bearing the CD4 receptor, principally T lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages, and disease progression features a gradual loss of CD4 cells with a concomitant increase in viral burden.1-3 Recent investigations have attempted to clearly define the infected and virus-producing T-cell subgroup by focusing on the two general subsets of CD4 T lymphocytes: CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO).

T-lymphocyte cell-surface isoforms, CD45RA (naive) and CD45RO (memory), are formed by alternative splicing of the mRNA4 and phenotypically represent functionally different subsets. T cells expressing a predominance of CD45RA respond well to mitogenic stimulation, express low levels of adhesion molecules, produce few cytokines, and differentiate into CD45RO cells when activated. In contrast, T cells with a predominant CD45RO phenotype respond well to recall antigens, express adhesion molecules, modulate B-cell responses to facilitate Ig production, and produce many cytokines.5-13

There have been conflicting reports as to whether one or both of these CD45 subsets are susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether RA or RO cell loss during HIV-1 disease is due to direct or indirect results of viral infection. In vivo and ex vivo studies of HIV-1–infected cells using cell fractionation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques demonstrated a preferential infection of the RO subset; however, culture methods were not developed to demonstrate preferential infection after cell expansion.14

Other recent investigations measuring HIV-1 cells in patients by flow cytometric analysis (FCA) indicate a loss of the RO subset early in the course of HIV-1 infection, followed by depletion of both RA and RO subsets as the disease progresses.15,16 In contrast, other groups using similar methods report an equal loss of RA and RO subsets early in the infection, with increasing loss of both subsets as the disease progresses.17 18

Roederer et al19 also used FCA to characterize a large group of HIV-1–infected patients with low CD4 counts (<500/μL). Although the primary focus of their study was to investigate CD8 naive cell loss, they also demonstrated a profound loss of the CD4 naive subset with a concomitant increase in the CD4 memory subset. This study and the others did not use virologic culture methods to examine cell loss due to direct and indirect effects of HIV-1 infection.

In the present study, we use unique cell culture techniques20 to preserve the RA phenotype during cellular proliferation and examine, by virologic culture methods and flow cytometry, the fate of purified RA and RO cells when subjected to in vitro HIV-1 infection. We demonstrate a reduced capacity for viral production in RA cells compared with RO cells when unstimulated cultures are maintained postinfection, suggesting the existence of an unstable HIV-1 intermediate in the RA population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of RO and RA populations.Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from normal healthy donors were separated from whole blood by gradient density separation (Lymphocyte Separation Medium; Organon Teknika, Durham, NC) and were washed two times in phosphate-buffered saline. Macrophages were removed by plastic adherence. CD4 cells were purified by column exclusion (Human CD4 Subset Column Kit; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Purified CD4 cells were further separated into pure RA and RO populations by negative selection using anti-CD45RA (clone L48) and anti-CD45RO (clone UCHL-1) monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and anti–mouse IgG magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as previously described.20

Culture conditions and viral infection.To prepare lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced monokine supernatant (LS), adhered macrophages (approximately 2 × 105) were incubated in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, and 1 μg/mL LPS (Sigma, St Louis, MO). After 24 hours, the supernatants were filtered (0.2 μm) and stored at −20°C.

As a prerequisite to infection, RA and RO cells were first incubated for 3 days in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, and 50% LS. RA and RO cultures were then infected with HIV-1 (Lai) at a multiplicity of infection of 10−3 or 5 × 10−4, incubated for 3 hours, and washed one time in RPMI 1640. After infection, the cultures were either suspended in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, 50% LS, and 10% purified interleukin-2 ([IL-2] Advanced Biotechnologies Inc, Columbia, MD) or phytohemagglutinin antigen (PHA)-stimulated (0.05% PHA; DIFCO Laboratories, Detroit, MI) at 20 hours postinfection. LS and IL-2 for the appropriate cultures were replenished at 3-day intervals. The use of LS plus IL-2 supplementation after infection provided physiologic activation signals for the cultures and maintained the RA phenotype during prolonged culture. Culture supernatant samples were taken approximately every 3 days for analysis by reverse transcriptase (RT) assay. Parallel uninfected cultures were similarly instituted as controls.

For determination of viral production when PHA-stimulated at various time points postinfection, RA and RO cells were exposed to HIV-1 (Lai) for 3 hours, washed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution without calcium or magnesium (HBSS), and then treated with 1 mL trypsin (0.05% trypsin, 0.53 mmol/L EDTA; GIBCO, Gaithersburg, MD) per 2 × 106 cells for 30 minutes at 37°C.21 The effectiveness of this protocol on extracellular HIV-1 removal was verified in preliminary experiments comparing p24 antigen levels in cellular lysates after infection at 37°C and 0°C (data not shown).21 After trypsin treatment, cells were washed three times in HBSS and maintained in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, and 50% LS. Aliquots of 106 cells were removed from these cultures on days 4, 7, and 10 and PHA-stimulated, and supernatants were taken for RT analysis every 2 days.

FCA.Two-color FCA was performed on cells stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD45RA and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 (Leu-3a), FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 and PE-conjugated anti-CD45RO, FITC-conjugated anti-CD45RA and PE-conjugated anti-CD45RO, or FITC-conjugated anti-CD45RA and PE-conjugated anti-CD62L (all from Becton Dickinson). Analyses were made on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems) using the Consort 30 software program.

Assays for viral detection and cell proliferation.Quantitation of HIV-1 replication by RT assay of culture supernatants was made using the methods reported by Willey et al.22 Results were determined on a Packard Matrix 96 Direct Beta Counter or as pixel values from a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). HIV-1 antigen detection was performed using the Coulter HIV-1 p24 Antigen Assay as directed by the manufacturer (Coulter Corp, Miami, FL).

Cell proliferation assays were performed in triplicate using 1 × 105 cells per well pulsed with 1 μCi 3H-thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Costa Mesa, CA) per well, and the cells were harvested 18 hours later. Tritiated thymidine uptake was determined on a Packard Matrix 96 Direct Beta Counter (Downers Grove, IL).

RESULTS

Purity of RA and RO subsets.In preliminary experiments, IL-2–induced HIV-1 infection of unseparated lymphocyte populations indicated that RO cells were being lost at a faster rate than RA cells. To clarify this issue, we first purified RA and RO subsets so that by FCA the populations consisted of 90% RA and 81% RO cells, respectively (Fig 1). Minor groups within these populations were 7% CD45RA+/CD4− in the RA population, and 9% CD45RO+/CD4−, 4% CD45RO−/CD4+, and 7% CD19−/CD56−/CD8− in the RO population (Fig 1). Similar percentages were attained in subsequent preparations. To further characterize the RA subset, cells were stained before infection with anti-CD62L, and 77% of the RA subset expressed a high density of the CD62L receptor (data not shown). CD4 receptor expression in RA and RO populations after isolation was similar when measured by FCA, with a mean channel fluorescence of 182 and 191, respectively (data not shown).

Purification of CD4 subsets. Ungated 2-color flow cytometric stain of (A) CD45RA and CD4 and (B) CD45RO and CD4 cultures after purification. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

Purification of CD4 subsets. Ungated 2-color flow cytometric stain of (A) CD45RA and CD4 and (B) CD45RO and CD4 cultures after purification. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

Maintenance of the RA population.To determine the growth dynamics of individual subsets in culture with IL-2 and LS, we examined uninfected RA and RO populations by FCA during a 2-week period. Eleven days after IL-2/LS treatment, 43.3% (39%/90%) of RA cells retained their phenotype (Fig 2). By day 11 in culture, 11% of the cells had converted to the CD45RO+/CD4+ phenotype and an additional 46% (Fig 2) were found to be CD45RO+/CD4− and CD3+ (data not shown). In comparison, the CD45RO+/CD4+ population 11 days after IL-2/LS treatment remained unchanged (78% CD45RO+/CD4+) (Fig 2).

Maintenance of phenotype expression in the CD4 subsets. Two-color FCA of (A) CD45RA and CD4, and (B) CD45RO and CD4 uninfected lymphocyte populations maintained for 11 days in RPMI 1640, 10% IL-2, and 50% LS. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

Maintenance of phenotype expression in the CD4 subsets. Two-color FCA of (A) CD45RA and CD4, and (B) CD45RO and CD4 uninfected lymphocyte populations maintained for 11 days in RPMI 1640, 10% IL-2, and 50% LS. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

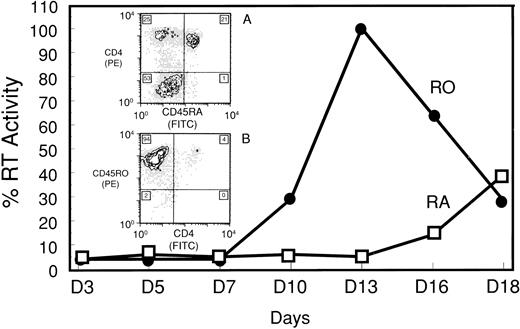

Susceptibility of RA and RO subsets to HIV-1 infection.The susceptibility of pure CD45 subsets to HIV-1 infection was determined by LS supplementation and induction with IL-2, a culture system that permitted prolonged maintenance of the original cellular phenotypes. After day 7 postinfection, RT activity in the RO culture supernatant dramatically increased in response to IL-2 induction and peaked by day 13. In marked contrast, IL-2–stimulated RA cultures showed little capacity to support HIV-1 replication. Only a small increase in supernatant RT activity of RA cultures was detected by day 13 (19-fold less than RO), which eventually reached only about 40% of the peak activity of the RO culture (Fig 3). In subsequent experiments, results were highly reproducible with respect to the kinetics and magnitude of virus production (data not shown).

IL-2–induced HIV-1 production in CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO) purified subsets. RT assay of supernatants from IL-2–stimulated, HIV-1–infected RA and RO cultures. Peak RT activity (day 13) showed a 19-fold difference between the 2 cultures. RT activity was converted to a percent based on maximal activity of the RO culture. Cell proliferation of the corresponding uninfected cultures was measured by 3H-thymidine uptake. Stimulation indices for the RA culture on days 7 and 10 were 3.71 and 4.34, respectively. The corresponding results for the RO culture on days 7 and 10 were 3.62 and 5.16, respectively. Inserts, 2-color FCA of IL-2–stimulated, HIV-1–infected (A) RA and (B) RO cultures 18 days postinfection. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

IL-2–induced HIV-1 production in CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO) purified subsets. RT assay of supernatants from IL-2–stimulated, HIV-1–infected RA and RO cultures. Peak RT activity (day 13) showed a 19-fold difference between the 2 cultures. RT activity was converted to a percent based on maximal activity of the RO culture. Cell proliferation of the corresponding uninfected cultures was measured by 3H-thymidine uptake. Stimulation indices for the RA culture on days 7 and 10 were 3.71 and 4.34, respectively. The corresponding results for the RO culture on days 7 and 10 were 3.62 and 5.16, respectively. Inserts, 2-color FCA of IL-2–stimulated, HIV-1–infected (A) RA and (B) RO cultures 18 days postinfection. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

In IL-2–induced cultures, FCA of HIV-1–infected cultures on day 18 indicated that 21% of RA cells retained their original phenotype. Twenty-five percent of the culture had shifted to a RO phenotype and 53% were a nonstaining population (Fig 3, inset A). The nonstaining population was similar to that seen on day 11 in the uninfected RA culture. In contrast, only 4% of the RO population remained CD4+, as 94% of the infected culture shifted to a CD45RO+/CD4− phenotype (Fig 3, inset B). Results on days 7 and 10 showed that both uninfected RA and RO cultures proliferated to a similar extent in response to IL-2 treatment (Fig 3).

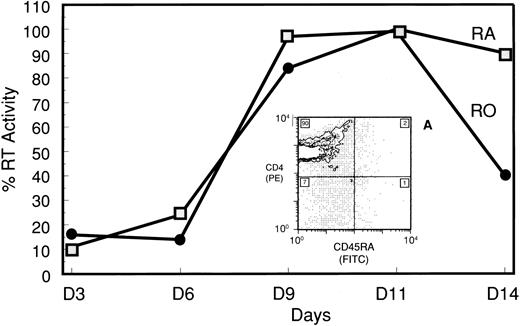

The competency of the purified subsets to support HIV-1 replication under more standard culture conditions was confirmed using PHA stimulation. Here, induction of RT activity for both cultures was nearly identical in response to PHA, increasing on day 6 and peaking by day 11 (Fig 4). FCA of the uninfected RA culture on day 7 post-PHA indicated that all RA cells had shifted to a CD45RO+/CD4+ phenotype (Fig 4, inset A).

PHA-induced HIV-1 production in the CD45RA+/CD4+ subset and conversion to CD45RO phenotype. RT assay of supernatants from HIV-infected CD45RA+/CD4+ and CD45RO+/CD4+ cultures that were PHA-stimulated 20 hours postinfection. RT activity was converted to a percent based on maximal activity of the CD45RO+/CD4+ culture. Insert A, 2-color FCA of PHA-stimulated, uninfected CD45RA+/CD4+ cells 7 days after stimulation. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

PHA-induced HIV-1 production in the CD45RA+/CD4+ subset and conversion to CD45RO phenotype. RT assay of supernatants from HIV-infected CD45RA+/CD4+ and CD45RO+/CD4+ cultures that were PHA-stimulated 20 hours postinfection. RT activity was converted to a percent based on maximal activity of the CD45RO+/CD4+ culture. Insert A, 2-color FCA of PHA-stimulated, uninfected CD45RA+/CD4+ cells 7 days after stimulation. The number in each quadrant is the population percentage.

To further explore the mechanism by which RA cells exhibited a reduced capacity for HIV-1 replication, HIV-1–infected RA and RO cultures were PHA-stimulated at various time points postinfection. Unlike the previous PHA-induction experiment, purified RA and RO cells were treated with trypsin after exposure to HIV-1 to prevent carryover of extracellular virus that might infect any RA cells upon conversion to RO, as well as to examine viral fusion and entry while the cells retained their original phenotype. Clear evidence of viral fusion and entry in RA cells was observed by quantifying intracellular p24 antigen immediately after infection and subsequent treatment with trypsin (RA, 17 pg/mL p24 antigen; RO, 29 pg/mL p24 antigen). Furthermore, RA cultures stimulated with PHA on day 4 postinfection expressed HIV-1 in a kinetic fashion analogous to RO cultures (Fig 5). RA cultures that were PHA-stimulated before day 4 (data not shown) or on day 4 (Fig 5) postinfection produced peak levels of virus equivalent to or greater than the levels in RO cultures.

Delayed PHA induction of HIV-1–infected CD45RA+/CD4+ and CD45RO+/CD4+ cultures. Infected cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, and 50% LS. On days 4, 7, and 10 postinfection, aliquots of 106 cells from each culture were removed and PHA-stimulated. After PHA stimulation, supernatants were collected every 2 days to determine RT activity, which is expressed as pixel values from PhosphorImager analysis.

Delayed PHA induction of HIV-1–infected CD45RA+/CD4+ and CD45RO+/CD4+ cultures. Infected cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640, 10% human AB serum, and 50% LS. On days 4, 7, and 10 postinfection, aliquots of 106 cells from each culture were removed and PHA-stimulated. After PHA stimulation, supernatants were collected every 2 days to determine RT activity, which is expressed as pixel values from PhosphorImager analysis.

Hypothetical fate of CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO) lymphocyte subsets in vivo during HIV-1 infection. (1) Infected thymic/precursor emigrants allow fewer cells into the peripheral circulation, resulting in a lower RA population. (2) A lower RA population leads to less differentiation into RO cells, resulting in a reduced RO population. (3) Infected RO cells are lost and cytokine feedback to stimulate RA proliferation is decreased, resulting in both lower RA and RO populations.

Hypothetical fate of CD45RA+/CD4+ (RA) and CD45RO+/CD4+ (RO) lymphocyte subsets in vivo during HIV-1 infection. (1) Infected thymic/precursor emigrants allow fewer cells into the peripheral circulation, resulting in a lower RA population. (2) A lower RA population leads to less differentiation into RO cells, resulting in a reduced RO population. (3) Infected RO cells are lost and cytokine feedback to stimulate RA proliferation is decreased, resulting in both lower RA and RO populations.

The events resulting in proviral integration in the RA population were collectively examined by PHA stimulation of the cultures on days 4, 7, and 10 postinfection. Infected RA cultures that were PHA-stimulated at day 7 postinfection had a markedly reduced capacity to replicate HIV-1 compared with similarly treated RO cultures (Fig 5). Furthermore, the ability of RA cells to replicate HIV-1 was completely lost in day 10 PHA cultures (Fig 5). In contrast, RO cells were still capable of replicating HIV-1 to peak levels equivalent to or greater than those in day 4 and day 7 PHA cultures (Fig 5). By 3H-thymidine uptake, RA and RO cultures both responded well to PHA stimulation when tested during the course of day 7 and day 10 cultures. Additionally, at these time points, both cultures contained equivalent numbers of viable cells by trypan blue exclusion (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The study presented here, using a modified culture system that permits in vitro proliferation and retention of a purified RA subset, has demonstrated that this cell subpopulation is significantly less capable of supporting HIV-1 replication than the RO subset. The RA subpopulation was found to be greatly reduced in its capacity to produce virus particles when compared with the RO subpopulation, and the difference in viral production between the subsets was reflected not only in the slower kinetics of virus replication but also in the loss of inducible virus.

Selective losses of CD4 T lymphocytes in HIV-1–infected individuals is a distinguishing feature of progression to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). A number of investigations attempting to unravel the selective functional loss of T-cell responsiveness have suggested that decreases in both T-cell proliferation and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activities occur during AIDS progression. Furthermore, in one study, relative selective phenotypic losses within the CD4 population have been attributed to the naive subset.19 Other studies have shown that the major population of infected CD4 cells reside in the memory subset and are attributed to the functional abnormalities observed in AIDS.14 Whereas both RA (naive) and RO (memory) cells contribute to the overall cellular immune response, this disparity between the subset observed to be infected and the subset that appears to be depleted in vivo must be linked to the overall pathogenesis.

Recently, it has been reported that in vitro naive uninfected T cells in the absence of antigenic stimulation could be activated with cytokines to proliferate, while retaining their phenotype and effector function.20 If such an antigen-independent pathway were operational in vivo, it would predict that this mechanism might contribute to peripheral expansion and maintenance of the naive population without conversion to the memory phenotype, thus preserving the naive pool. We have applied this novel pathway of activation to gain insight into the influence that HIV-1 might have on effector cell recruitment and maintenance of these two crucial immune subsets in vivo.

A previous study identified preferential HIV-1 infection of the memory subset, but did not address the susceptibility to infection of either naive or memory cells or the fact that activation of naive cells causes conversion to the memory phenotype.14 In our studies, preparatively purified CD45RA+/CD4+ cells, induced to proliferate by a novel activation pathway and to retain a majority of the CD45RA+/CD4+ phenotype, were recalcitrant to productive infection induced by IL-2 treatment. The virus that was produced in RA cultures may be derived from a minor population of cells such as the CD45RA+/CD62L low-density phenotype.19

The mechanism resulting in a decreased HIV-1 expression rate in the RA relative to the RO population could be at several points in the infection cycle. Our data from the day 4 PHA experiment indicate that HIV-1 can fuse with and enter RA cells. In this experiment, the cells were treated with trypsin after infection to ensure that subsequent HIV-1 expression was not a consequence of intact virions remaining adhered to the RA cell surface and entering the cell concordant with an activation signal. Therefore, it is probable that the restricted viral replication in RA cells is due to an inability of HIV-1 to completely reverse-transcribe23 or achieve nuclear transport and integration24 until the necessary cellular activation signals are received. This possibility is further supported by the inability of RA cells to replicate HIV-1 if the activation signal is delayed 7 to 10 days postinfection, as also shown in our PHA experiment. However, this experiment cannot resolve at which point between viral fusion and proviral integration the defect in RA cells resides.

Alternative explanations for the loss of HIV-1 expression in RA cells relative to RO cells other than a lack of proviral integration must be considered. After infection, HIV-1 may integrate in RA cells but enter a state of absolute latency. It might be argued that in such a latent state, expression from the integrated provirus requires induction signals other than those provided by PHA or IL-2 treatment. However, the temporal loss of the capacity to replicate HIV-1 in PHA-treated RA cultures does not suggest that such a state of latency is achieved as an immediate consequence of infection. Therefore, integration and proviral latency in infected RA cells would have to occur in concert with the temporal loss of an unintegrated intermediate to produce the observed expression pattern. Integration during PHA-induced conversion of CD45RA naive cells to the CD45RO phenotype may result in proviral latency due to the nonphysiologic nature of the activation signal. It also remains possible that an unintegrated HIV-1 intermediate is inherently more stable in the intracellular environment of CD45RO cells, allowing for its prolonged maintenance postinfection before cellular activation, although this was not demonstrated in a recent study.25 Investigations are currently under way using our system to determine the HIV-1 integration status of these cells.

Clearly, intracellular pathways leading from engagement of the T-cell receptor versus pathways induced by IL-2 and monokines may have different effects on HIV-1 postfusion complex stability and nuclear transport. This is further evidenced by a recent study investigating T-cell receptor signaling of cells. Recently, it was reported that costimulation of CD4+ cells by anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 cross-linking provided a proliferative signal to the cells that conferred resistance to infection by HIV-1. Furthermore, this antiviral effect occurred early in the viral life cycle, similar to our findings.26 In another study, enhanced viral replication was seen in RO cells induced by T-cell receptor cross-linking; however, they were less responsive in the capacity to proliferate.25 Such information further supports intracellular control and separation of events leading to proliferation and virus production following ligand activation.

In a previous investigation, HIV-1 proviral DNA was detected in purified naive CD4 lymphocytes in six of nine patients by PCR.14 This would indicate that either HIV-1 integration had occurred in these cells or an unintegrated and/or partially reverse-transcribed RNA species was detected. This finding is supported by studies detecting proviral DNA sequences in unstimulated CD45RA cells 8 days postinfection.25 In another study, unintegrated HIV DNA persisted through day 14 postinfection of unfractionated quiescent lymphocytes, and integration occurred only upon activation.24

It was important to determine phenotypically which subsets survived and which were being lost to infective processes after weeks in culture under this novel activation procedure. FCA of RA cultures indicated the emergence of a CD45RA−/CD4− subpopulation. This may indicate a switch from RA to CD45RO+/CD4− or may be the result of outgrowth of a minor contaminating population. Because we did not compare long-term culture in LS plus IL-2 against a mixture of recombinant monokines plus IL-2, we cannot rule out any effects that LPS may have in long-term culture. Such a CD4− subpopulation never appeared in RO cultures or in PHA-activated cultures. Since this subpopulation appeared to expand in all long-term RA cultures regardless of infection, it was interpreted to be uninfected. However, this is yet to be confirmed, since analysis of viral production was halted at 3 weeks, and it is possible that this emerging subset was infected but resisted viral-induced cytopathic effects due to surface CD4 loss. Since we did not rely on CD4 downmodulation as an indicator of viral infection, this double-negative CD45RA−/CD4− subpopulation, which grows out, was not interpreted to confound the results.

These in vitro findings are in accordance with other studies that have analyzed the predominance of CD4 T-cell subsets in HIV-1–infected individuals by FCA. Klimas et al27 identified 25 HIV-1–positive asymptomatic males with relatively early infection, and found a loss in the CD4 memory subset. Another study, using 49 HIV-1–positive patients, found lower CD4 memory subsets in 61% of these individuals, with this percentage corresponding to the asymptomatic and persistent generalized lymphadenopathy group. The remaining 39% were patients with AIDS-defining illnesses and decreased CD4 counts, reflecting no selective loss between memory and naive cells.15 Still another study found lower CD4 memory subsets in asymptomatic HIV-1–infected individuals.28 These investigations have clearly identified CD4 memory subset losses in patients with relatively early and late disease progression.

The loss of the RO subpopulation to HIV-1 infection with depletion and changes in the RA population, seen in our data and those of others, is suggestive of a potential mechanism for AIDS pathogenesis. Several possible explanations for the in vivo mechanism of cell loss exist. One might suggest that infected thymic precursor emigrants allow fewer RA cells into the peripheral pools. This would lead to a lower RA population, resulting in fewer cells differentiating into RO. Secondly, loss of RO cells due to infection might result in less supportive cytokine production and cytokine feedback for RA expansion and infection combined with a shorter expected cell life, making the RO subpopulation particularly susceptible to loss.29 Furthermore, chronic immune stimulation30-32 persisting from the presence of HIV and other infections serves to activate memory populations, resulting in continuous RO infection and subsequent loss. These potential mechanisms of cellular elimination may explain the dysregulated recruitment of cells into the naive pool (Fig 6).

In conclusion, the ability to infect cells under more physiologic conditions and to maintain and proliferate RA cells in culture has enabled us to demonstrate differences in the rate of viral production and susceptibility between naive and memory subpopulations. The ability of RA cells to replicate HIV-1 appears to be restricted at a postfusion event, possibly before proviral integration but after reverse transcription. These in vitro findings may be helpful in explaining possible in vivo CD4 loss and replenishment dynamics.

Address reprint requests to Thomas M. Folks, PhD, RDB/DASTLR/NCID/CDC, MS-G19, 1600 Clifton Rd NE, Atlanta, GA 30333.