In this issue of Blood, Bagratuni et al1 develop a multistep clinical model of Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) against which genome sequencing has been anchored to aid prognostication. The ability to predict an individual patient’s survival or response to specific therapy is a pillar of modern cancer medicine. For patients with WM following the identification of mutations in MYD88 and CXCR4, customized therapy became a reality.2 However, the ability to reliably predict an individual patient’s prognosis has remained difficult. Fundamental insights into cancer biology have been derived by studying the progression of precursors to symptomatic stages of cancer. Importantly, superimposing genomics on top of clinical staging systems has allowed individual prognostication. For WM there are now indications that individual prognostication and interception of the disease at precursor stages is becoming a reality.

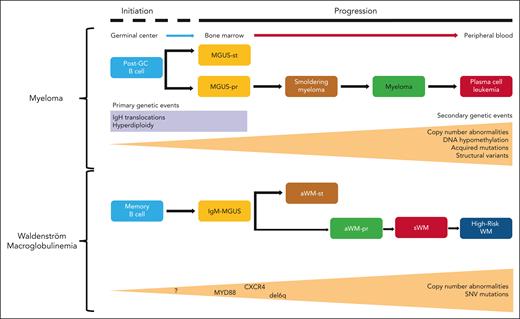

Insights into such models come from the related plasma cell dyscrasia, multiple myeloma (MM) where the relationship of monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS), smoldering MM, newly diagnosed MM, and relapsed MM, when integrated with genomics has delivered clinical utility3,4 (see figure). The immortalization of a myeloma initiating cell through a limited number of chromosomal translocations or hyperdiploidy occurs decades prior to clinical presentation.3,4 Once immortalized the random acquisition of mutations can lead to disease progression. Most mutations either exert a negative impact on fitness or are removed by the immune system. However, rare, acquired variants that associate with a positive impact on survival benefit lead to increased clonal fitness, the net result of which is disease progression. Despite the apparent randomness of these evolutionary processes, a temporal relationship between a limited number of key oncogenic drivers develops.

Multistep disease models of MM and WM. (Upper panel) The current clinical and genetic multistep model of the initiation and progression of MGUS to MM. (Lower panel) The newly proposed multistep model of WM where sequencing data have been mapped onto the clinical disease stages of IgM-MGUS, aWMst, aWMpr, and symptomatic WM. Increasing tumor mutational burden and CNA are characteristics of disease progression. SNV, single nucleotide variant.

Multistep disease models of MM and WM. (Upper panel) The current clinical and genetic multistep model of the initiation and progression of MGUS to MM. (Lower panel) The newly proposed multistep model of WM where sequencing data have been mapped onto the clinical disease stages of IgM-MGUS, aWMst, aWMpr, and symptomatic WM. Increasing tumor mutational burden and CNA are characteristics of disease progression. SNV, single nucleotide variant.

Could such a system be developed for WM? Clinically, immunoglobulin M (IgM)-MGUS and asymptomatic WM, are primarily differentiated by disease bulk and have a risk of progression of 1.5% to 12%.5,6 Clinical stage WM is differentiated from precursors by the presence of symptoms. The genetic architecture underlying precursor and clinical stages of WM has remained largely unclear until now. The multistep model of WM described by Bagratuni et al proposes a link between IgM-MGUS, asymptomatic WM (aWM), and symptomatic WM (sWM) and refines aWM into asymptomatic stable WM (aWMst) and asymptomatic progressive WM (aWMpr).

Whole exome sequencing (WES) is used to characterize the mutation pattern at each disease stage with the aim of defining the risk of progression and potentially the need for therapy. Although the study has some limitations, such as its relatively small sample size and the absence of paired nontumor samples for all cases, these are mitigated by the rarity of the disease and the novelty of the approach taken. WES corroborated the presence of known mutations in MYD88 and CXCR4,7 and identified other recurrently mutated genes including KMT2C, NOTCH1, ARID1B, KMT2D, ARID1A, and CD79B. In line with the proposed disease model, patients had a progressive increase in bone marrow infiltration at later stages and this was accompanied by an increase in tumor mutational burden. The prevalence of mutations increased at late stages with these stages having higher frequency of mutations in CD79B and CREBBP, implying a role as drivers of progression.

Interestingly, the MYD88L265 variant allele frequency (VAF) was significantly higher in aWMpr, suggesting it becomes more clonal over time and potentially suggests the possibility of a pre-WM MYD88 nonmutated disease stage. In sWM, MYD88 mutations are predominantly clonal, whereas CXCR4, EZH2, KMT2D, NFKB1, ARID1A, ARID1B, and NOTCH3 are subclonal, aligning them with a role in progression. Counterintuitively, however, CXCR4 was more frequently mutated in aWMst by comparison with patients with aWMpr, suggesting that its role in progression is more complicated than previously thought. The authors also integrate copy number abnormalities (CNA) into their model and show that patients with IgM-MGUS and aWMst have significantly less CNA compared to those with aWMpr and sWM. They show that del6q is more frequent in sWM by comparison with stable precursors. At first glance, this finding is somewhat at odds with the observation that del6q and dup18q are clonal in three-quarters of patients. However, using paired samples from different stages of the model they clarify a role for del6q in progression.

The real value of WES is its potential predictive value for risk progression based on the presence of more than 4 genomic abnormalities. By integrating the presence of driver mutations, CNAs and clinical parameters, patients can be stratified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on a risk score. Using this score on a validation cohort, all patients with aWMpr were successfully identified as being high-risk, however, there was a small false positive rate with some aWMst and IgM-MGUS cases being identified as high-risk. Patients with no WM-relevant mutations had low prediction risk scores.

Biologically the authors clearly identify intraclonal heterogeneity in WM consistent with Darwinian evolutionary processes being mediators of progression. This supposition is also supported by an increasing mutational burden, late acquisition of recurrent driver mutations, and the acquisition of del(6q) at later stages. Although the work is novel, the study is small and is unlikely that it will be the final word in this area. It does, however, set the field up for a lively debate about several important areas. Outstanding questions include the presence of low-level VAF for MYD88 at early disease phases raising the possibility of a pre-WM disease phase before the acquisition of MYD88 mutations. The results also raise the question of whether there are subsets of IgM-MGUS that are entirely benign and never progress to clinical stages. Moving forward it is important to integrate other biological insights such as the 2 molecular subsets of WM MBC-like and PC-like8 and the role of the immune microenvironment.9 Taken together with other recent publications this work suggests that genomic profiling and precision medicine will play an important role in WM management and will identify patients who can be reassured about their low-risk of progression and identify patients at high-risk of progression, who may be suitable for interception strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.