Visual Abstract

Platelets play crucial roles in hemostasis, thrombosis, and immunity, but our understanding of their complex biogenesis (thrombopoiesis) is currently incomplete. Deeper insight into the mechanisms of platelet biogenesis inside and outside the body is fundamental for managing hematological disorders and for the development of novel cell-based therapies. In this article, we address the current understanding of in vivo thrombopoiesis, including mechanisms of platelet generation from megakaryocytes (proplatelet formation, cytoplasmic fragmentation, and membrane budding) and their physiological location. Progress has been made in replicating these processes in vitro for potential therapeutic application, notably in platelet transfusion and bioengineering of platelets for novel targeted therapies. The current platelet-generating systems and their limitations, particularly yield, scalability, and functionality, are discussed. Finally, we highlight the current controversies and challenges in the field that need to be addressed to achieve a full understanding of these processes, in vivo and in vitro.

Introduction

Platelets are sentinels of vascular integrity.1 They monitor blood vessel walls, and upon detection of injury, adhere and rapidly aggregate to form a clot, which prevents excessive blood loss in hemostasis but can also form an occlusive thrombus in pathological settings.2,3 Our understanding of platelet biology and their multiple functions is now substantial,1,3,4 but we still currently lack a detailed understanding of their formation. This is partly a product of the complexity of this uniquely mammalian process. Platelets derive from large polyploid megakaryocytes (MKs), which differentiate from hematopoietic stem cells principally in the bone marrow niche.5-9 Each MK is estimated to produce up to 3000 platelets.7,8,10 Evidence shows that multiple MK phenotypes exist, including distinct platelet-producing and immune subtypes. Although the lung may harbor predominantly immune MKs, the absolute number may be greater in the marrow.11-15 MK maturation and phenotyping is discussed extensively elsewhere.9,16-18

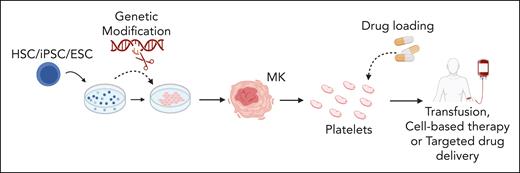

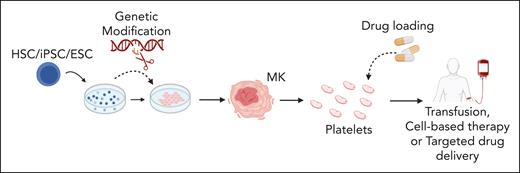

There are multiple potential applications for in vitro–generated platelets, schematically summarized in Figure 1, including discovery research, biomedical testing, and tailored therapies. A high-yield platelet generation system could allow constant availability of fresh, nonimmunogenic platelets for clinical transfusion, thereby overcoming reliance on donor-derived platelets with short shelf lives (5-7 days) and contamination risks.19,20 Anucleates cannot be genetically modified once they are generated, which makes bioengineering platelets challenging,3 and therefore, systems capable of producing platelets ex vivo from modified precursors are being developed. Tailored therapies using bioengineered platelets include factor VIII delivery for treatment of hemophilia A,21 targeted delivery of fibrinolytics22 or other agents,23 and modification of granule content to promote tissue repair.24

Proposed applications of in vitro-produced platelets. Stem cells (human-derived HSCs, iPSCs, and ESCs) are differentiated into MKs. During culture, stem cells or derived MKs can be genetically modified to modulate expression of key genes. Subsequently, native or genetically modified MKs may be used to generate platelets tailored for specific therapeutic purposes. The uses of these in vitro–derived platelets include cell-based therapies, transfusion medicine, and targeted drug delivery for a range of clinical issues including thrombocytopenia, ischemic and inflammatory conditions, enhanced tissue repair, and targeting processes in cancer development. ESCs, embryonic stem cells; HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Proposed applications of in vitro-produced platelets. Stem cells (human-derived HSCs, iPSCs, and ESCs) are differentiated into MKs. During culture, stem cells or derived MKs can be genetically modified to modulate expression of key genes. Subsequently, native or genetically modified MKs may be used to generate platelets tailored for specific therapeutic purposes. The uses of these in vitro–derived platelets include cell-based therapies, transfusion medicine, and targeted drug delivery for a range of clinical issues including thrombocytopenia, ischemic and inflammatory conditions, enhanced tissue repair, and targeting processes in cancer development. ESCs, embryonic stem cells; HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells. Figure created with BioRender.com.

This review aims to cover our current understanding of how platelets are made, both in the body and outside the body in artificial systems. The key uncertainties remain the identification of the sites of platelet biogenesis and their relative contributions, the signaling mechanisms that control the process, and the molecular mechanisms by which MKs sense their environment. The understanding of these uncertainties are incomplete but the current progress will be discussed. It is also important for there to be discussions around the controversies and challenges within the field, which currently hinder progress. These are largely the consequence of clarity over definitions of structures, such as proplatelets, and deficiencies in the techniques used to visualize or quantify them, particularly in vivo. These are areas that the field needs to resolve, and some of these are listed in Table 1 with suggested solutions.

Platelet generation in vivo

Since the discovery of platelets by Giulio Bizzozero almost 150 years ago, there have been substantial advances in our understanding of their role and the regulation of their function.1 There is compelling evidence that supports the production of platelets through multiple mechanisms at distinct sites, and redundancy is a common feature of mammalian physiology, particularly when the processes are essential for life. The mechanisms and locations of thrombopoiesis that are discussed hereafter are not, necessarily, mutually exclusive.

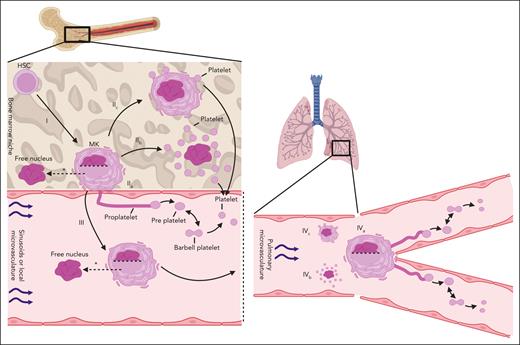

Currently, 3 major cellular mechanisms for platelet generation are hypothesized and include (1) proplatelet formation, (2) cytoplasmic fragmentation (also called explosive fragmentation), and (3) membrane budding.27-31 These mechanisms may occur at multiple sites in the adult mammal with the 2 most prominent sites being (1) the interface of the bone marrow niche and sinusoidal vasculature and (2) the microvasculature of the body, principally the lungs.28,29 In the following sections, the production of functional platelets is described. There is significant heterogeneity in what is classified as a functional platelet. This is discussed in Table 1 and within “Generating platelets in vitro,” including a call for united parameters to define a functional platelet.

Mechanisms of platelet generation

The molecular and cytoskeletal mechanisms through which proplatelet extensions from MKs are formed have been studied and reviewed in detail25,26,32-36 and are summarized in Figure 2. Some of the earliest observations come from Wright, who observed “giant cells” (which would later become known as MKs) with “nearly all the cytoplasm in the form of pseudopod-like processes” more than 100 years ago.37 The classical proplatelet model proposes that immobilized MKs extend long microtubule-driven extensions (proplatelets) from the bone marrow space into the flowing blood of the sinusoidal vessels. The extended membrane is subjected to shear forces that promote the pinching off of either long proplatelets or enlarged platelets called preplatelets (∼2-3 times the size of a platelet).28,33,38-41 Free-floating proplatelets can also pinch into preplatelets. Preplatelets deform into barbell-shaped objects (reversibly) before severing in the middle to produce 2 daughter platelets28,39,42 (Figure 2, IIa and IVa). These preplatelets and platelet barbells can also be found in circulating human blood.41 Becker and De Bruyn presented early in vivo data for the role of proplatelets in platelet production.43 They visualized the extending protrusions of the MKs from the bone marrow niche into sinusoids and suggested that this was the origin of platelets and larger cytoplasmic fragments (preplatelets).41,43 It is well established that proplatelets and platelet barbells exist in vivo and in vitro.33,39,43,44 Choi et al showed that platelets produced in static human-derived MK cultures via a proplatelet mechanism are functional (aggregate, express P-selectin, and integrin αIIbβ3 in response to agonists).44 However, Wang et al showed that platelet-like particles that were produced under static culture conditions were not comparable with donor platelets.45 Mouse intravital microscopy has been used to show that bone marrow–resident MKs release full proplatelets and other cytoplasmic fragments.40,46,47 In addition, imaged mouse lungs have shown platelet release from immobilized proplatelet-forming MKs.48 Platelet release from proplatelets in vivo is much more efficient than static in vitro cultures, which may indicate an important role for shear stress.49 Other factors such as endothelial signals are also likely key.50,51

Schematic of the hypothesized platelet production mechanisms in the bone marrow and the lung vasculature. Left-hand side: platelet production in the bone marrow. Right-hand side: platelet production in the lung vasculature. (I) HSCs differentiate and mature into MKs within the bone marrow niche. (II) Thrombopoiesis is hypothesized to occur via 3 different mechanisms in the bone marrow. (IIa) Proplatelet formation in which long, fine protrusions are extended from the bone marrow niche into the sinusoidal vasculature. Shear forces aid in the release of whole proplatelets or large preplatelets that interconvert into barbell platelets that pinch off to form 2 individual platelets. (IIb) Cytoplasmic (explosive) fragmentation in which case preformed platelet territories are released upon MK eruption. (IIc) Membrane budding in which case platelets are formed and released from the MK plasma membrane. (III) Whole MKs migrate out of the bone marrow niche, retaining or leaving behind their nucleus (as indicated by the dotted horizontal line in the nucleus), in the form of large protrusions driven by multiple membrane fusion events. MKs may generate platelets intravascularly as they passage within the venous vasculature. (IV) Thrombopoiesis occurring in the lung vasculature. (IVa) Immobilized MKs extend proplatelets and undergo similar platelet release mechanisms as seen in (IIc), (IVb) cytoplasmic fragmentation, and (IVc) membrane budding. ∗MKs may enucleate within the bone marrow niche26 or within the systemic vasculature50 before thrombopoiesis. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Schematic of the hypothesized platelet production mechanisms in the bone marrow and the lung vasculature. Left-hand side: platelet production in the bone marrow. Right-hand side: platelet production in the lung vasculature. (I) HSCs differentiate and mature into MKs within the bone marrow niche. (II) Thrombopoiesis is hypothesized to occur via 3 different mechanisms in the bone marrow. (IIa) Proplatelet formation in which long, fine protrusions are extended from the bone marrow niche into the sinusoidal vasculature. Shear forces aid in the release of whole proplatelets or large preplatelets that interconvert into barbell platelets that pinch off to form 2 individual platelets. (IIb) Cytoplasmic (explosive) fragmentation in which case preformed platelet territories are released upon MK eruption. (IIc) Membrane budding in which case platelets are formed and released from the MK plasma membrane. (III) Whole MKs migrate out of the bone marrow niche, retaining or leaving behind their nucleus (as indicated by the dotted horizontal line in the nucleus), in the form of large protrusions driven by multiple membrane fusion events. MKs may generate platelets intravascularly as they passage within the venous vasculature. (IV) Thrombopoiesis occurring in the lung vasculature. (IVa) Immobilized MKs extend proplatelets and undergo similar platelet release mechanisms as seen in (IIc), (IVb) cytoplasmic fragmentation, and (IVc) membrane budding. ∗MKs may enucleate within the bone marrow niche26 or within the systemic vasculature50 before thrombopoiesis. Figure created with BioRender.com.

The existence of proplatelets in vivo is clear, but their contribution to overall platelet production is contested. Potts et al showed that very low proportions of MKs form proplatelets when compared with those with membrane buds.30 Our group have used intravital correlative light electron microscopy to visualize the process of MK exit from the bone marrow space into the sinusoid in high resolution. This was followed by 3-dimensional (3D) volume reconstruction by electron microscopy, which demonstrated the presence of proplatelets in the sinusoidal space, although very few were directly connected to MK bodies. MKs were shown to extrude into the sinusoidal space as whole cells or large protrusions rather than as generally finer, microtubule-driven proplatelet extensions. The results of this study suggested that proplatelets are part of the platelet generation mechanism but may be formed within the vasculature rather than as extensions from the bone marrow niche.26

A second proposed mechanism, cytoplasmic fragmentation (Figure 2, IIb and IVb), involves prepackaging of platelets within the MK itself in regions called platelet territories. The MK then explodes and releases these internally generated platelets, leaving only the large MK nucleus behind.27,31 Phase-contrast microscopy has been used to capture this process in vivo.27,31 Multiple sources allude to fragmentation of MKs into platelets, both in bone marrow and lungs, however, much of these data are restricted to in vitro studies.27,31,52,53 It is also postulated that a chain of platelet territories within MKs are released when MKs fragment or explode, and these were termed protoplatelets.27 Key evidence for this mechanism was presented by Nishimura et al.54 They showed that bone-marrow resident MKs rupture and release platelet-like particles into the local circulation of live mice. Their data suggest that MKs can rupture to release a large number of platelets under acute situations that require increases in platelet count, such as inflammation. Interleukin-1α seems to be key in this process. The authors hypothesized that proplatelet formation contributed to steady-state platelet production and that cytoplasmic fragmentation was a compensatory stress mechanism.

Finally, membrane budding is a mechanism that proposes that platelets emerge and pinch off directly from the plasma membrane of a nonproplatelet-forming MK (Figure 2, IIc and IVc).30,55,56 Potts et al presented intravital microscopy data in support of membrane budding as the major mechanism of platelet production in mouse fetal liver and adult bone marrow.30 They suggested that membrane budding can account for 89% of the total number of platelets at steady state and that it was mechanistically distinct from proplatelet formation. The membrane buds on MK surfaces were platelet sized, had a cytoskeleton continuous with the MK, and were not products of apoptosis. Although MKs are often described as sessile in the bone marrow niche and spleen because they are not migrating or extending proplatelets,30,40 Potts et al showed that many of these cells are actually producing platelets via membrane budding. They confirmed proplatelet formation in the bone marrow, but platelet release from these proplatelet extensions was not observed.30 Italiano et al dispute these claims and instead suggested that the buds were microvesicles based on the differences in morphology and organelle content observed using transmission electron microscopy.57 A more comprehensive analysis of budding bone marrow–resident MKs is required.

Location of platelet generation

MKs can be found both within tissue spaces and the vasculature and therefore platelet generation may, in theory, proceed in either compartment. A mechanism for platelet migration from the bone marrow space into the vasculature, however, has not been uncovered to date.30 This weakens the theories of platelet release into the bone marrow space. One possible molecular mechanism may involve sphingosine-1-phosphate, which has been proposed to form a chemotactic gradient that guides the migration of platelets or proplatelet extensions from the marrow space into the sinusoids, although conflicting evidence has also been published.46,58

All mechanisms of platelet generation (proplatelet formation, cytoplasmic fragmentation, and membrane budding) have been proposed to occur in the bone marrow space or the vasculature.27,28,30,31 As mentioned, intravital visualization of platelet formation and release via membrane budding within the bone marrow niche has been shown.30 Cytoplasmic fragmentation of MKs has also been visualized in fixed human bone marrow and intravitally in rabbit bone marrow.27

In vivo evidence for proplatelet formation within bone marrow comes from studies that showed protrusion of the extensions of MKs into sinusoids.40,43,46 These protrusions are described as proplatelets, but with the limited resolution of intravital microscopy, it is more appropriate that they are termed protrusions. Using correlative light electron microscopy, we have shown that MK-derived structures in the sinusoidal space can be characterized as either large protrusions (>3 μm in diameter) or as proplatelets (≤3 μm).26 From this analysis, >90% of MK extensions from the marrow space were large protrusions and few were proplatelets. However, once detached from the MK cell body in the vascular space, 72% of the released extensions were proplatelets as opposed to large protrusions. This study has 2 key conclusions. First, MKs can migrate from the bone marrow niche into the circulation, which may facilitate platelet production at extramedullary sites.30,26,48 Second, intravascular platelet production likely occurs in the bone marrow, and this may involve proplatelet formation and extension within sinusoidal space. This highlights the need for defined criteria of proplatelet extensions and large protrusions, as discussed in Table 1.

The observation that MKs enter sinusoids, either with or without their nucleus (which seems to be left in the marrow space in some cells), suggests that platelet generation may take place at sites distant from the bone marrow.26 The lungs, in particular, have been proposed to be a site of thrombopoiesis partly because it is the first microvasculature encountered by MKs that are circulating in the vasculature from the marrow space. Lefrançais et al visualized platelet release from the end of MKs that formed proplatelets in the lung vasculature.48 Using this, they postulated that proplatelet-mediated platelet production in the lungs could account for ∼50% of all platelets in the blood. These MKs that produce platelets in the lungs were shown to be of bone marrow origin, because they were seen exiting the niche into the venous flow. The Poncz group has shown previously that, when MKs are intravenously transfused in mice, the observed increase in platelet number was principally associated with MK deposition in the lungs rather than in the bone marrow.30,26,45,48,59 They have also recently shown that recirculating mouse- and human-derived MKs release cytoplasmic fragments, which was associated with an increase in platelet count, in a catch-and-release style within the pulmonary vasculature.60 We also have shown recently that the passage of mouse MKs through pulmonary vasculature in an ex vivo heart-lung mouse model led to the generation of large numbers of platelets (discussed below).50 This model highlighted several key features of lung vasculature–based thrombopoiesis. Importantly, it was found that multiple rounds of MK recirculation in the lungs were required to prime MKs for platelet generation. An early step before platelet generation was the movement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell, followed by enucleation, which also has been observed by the Poncz group.60 Oxygen was also required for this process, and interactions with the local endothelium was likely to be a critical potentiator.50

Currently, a major challenge is to determine the relative contribution of different organs to the platelet biomass, whether that is intravascular (from marrow, lung, and potentially other organs) or directly from tissue spaces (principally marrow). One criticism of lung-based thrombopoiesis is that the number of MKs within the lung tissue is low, as suggested by Asquith et al.61 In that study, however, the lung vasculature was flushed before MK counting, and therefore counts were principally of lung-resident MKs rather than also including potential platelet-producing MKs in the vasculature of the lung.61 In addition, the residence time of MKs that transit through the pulmonary vasculature is likely to be less than an hour. In their ex vivo study, Zhao et al demonstrated that MKs could passage through the lung microvasculature, thereby substantially diminishing the number of intravascular MKs found in lung tissue. Interestingly, Potts et al showed low MK numbers in the lungs, but a relatively high proportion of those present were in a proplatelet conformation.30

Some reports argue that the low MK numbers found in blood and the paucity of MKs within the lung vasculature suggest a minor role for the lung in generating platelets.61-63 However, postpulmonary blood has been shown to have a higher platelet count than prepulmonary blood,64 thereby supporting the concept that platelet generation can occur in the lung vasculature. Computational data also have suggested that the number of MKs in circulating blood is sufficient to produce appropriate steady-state platelet numbers.65,66 In addition, ∼50% of patients with severe acute respiratory syndromes exhibit thrombocytopenia,67 suggesting a possible role for the lung in platelet generation. Interestingly, some patients with right-to-left shunting congenital heart defects have low platelet counts, which recover upon repair of the shunt, indicating that the lack of MK passage through the lungs may be sufficient to lower pulmonary platelet production.68

It has been proposed that the physical shape, molecular environment, and mechanical forces in the lung vasculature are supportive of platelet production.48 Notably, glycoprotein Ib-V-IX–von Willebrand factor (vWf) signaling in MKs can promote proplatelet formation,69 and pulmonary endothelial cells express very high levels of vWf.51,70 Moreover, shear stress and vWf binding, in tandem, promote greater proplatelet formation.71 Tropomyosin 4 (Tpm4)–/– mice provide key evidence for the existence of 2 distinct locations of thrombopoiesis that work independently of one another.50 Our work shows that tropomyosin 4 (Tpm4) is absolutely essential for lung vasculature–mediated thrombopoiesis in vitro, but given that Tpm4–/– mice have platelets (albeit at lower numbers than wild type mice), the inference is that Tpm4-independent platelet generation must also be possible at sites other than the lung.50 In other words, the data suggest that there may be at least 2 mechanistically distinct mechanisms that mediate platelet generation. More studies are required to understand the relative contributions of intravascular vs tissue-derived thrombopoiesis, bone marrow vs lung, and whether these switch in different systemic situations, such as hemostatic urgency or inflammation, and if compensatory mechanisms are at play.

Finally, there is evidence that the spleen may also provide an alternative site of platelet production.72,73 The spleen is a known reservoir of MKs, and recent work by Valet et al showed that the number of resident MKs and levels of thrombopoiesis increase during acute inflammation.72 The platelets produced appeared to be phenotypically distinct with greater expression of the leukocyte-interacting CD40 ligand. Increased platelet-leukocyte interaction mediates thromboinflammation and facilitates bacterial defense and the resolution of infection.72 This provides strong evidence for the involvement of multiple organ sites in MK maturation and possibly also platelet production and how these sites may change depending on systemic pathology. This also raises the question of whether different platelet production sites may have the capacity to produce different platelet phenotypes under different physiological or pathological conditions.

Generating platelets in vitro

Beyond a fundamental understanding of how mammalian systems generate platelets, a detailed understanding of thrombopoiesis will eventually enable the mimicking of in vivo biology to generate large numbers of platelets in vitro. In turn, sophisticated in vitro systems will help to provide clues about the fundamental mechanisms in thrombopoiesis in vivo. Since the 1990s, advances in cell culture techniques, bioreactors, and 3D biocompatible materials have been coupled with the emergence of new regenerative-medicine breakthroughs, such as the discovery of human embryonic stem cells74 and human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs).75,76 This has led to substantial advances in ex vivo platelet generation research with an increasing number of manuscripts being published on this topic every year.77 This section will review published in vitro platelet-producing systems by describing their design and comparing their platelet-producing efficiency with specific focus on the contrast with physiological processes in which a single MK is estimated to generate up to 3000 platelets. Table 2 summarizes this, including the source of input cells and assays used to characterize the generated platelets and their functionality as reported in the original article.

Using flow and shear stress

Soon after the discovery of thrombopoietin in 1994,95 the first functional human platelets were generated in vitro from CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells.44 Many iterations of cell culture systems have been developed in the subsequent years to differentiate stem cells into MKs and to push them toward proplatelet formation. The release of platelets into the media makes them easy to collect and analyze. However, in static culture, only ∼10% of human MKs release platelets96 and thus the yield of these systems remained low. For example Takayama et al estimated that 48 platelets were produced per initial stem cell, and Lu et al estimated that 6.7 platelets are produced per MK.80,79 In 2005, a 3-step culture system claimed to produce a high number of platelets per input CD34+ cell; however, no clear yield per input cell was stated, which makes direct comparison challenging.78

In 2009, high shear stress was found to play a critical role in in vitro platelet synthesis,69 which led many to apply flow in an attempt to enhance platelet production. Notably, building on their previously developed, perfused 3D hydrogel system that produced 20 platelets per starting cell in 2009,81 Lasky and Sullenbarger managed to increase platelet numbers two- to threefold in 2011 by introducing shear forces to mimic bone marrow venous sinuses and increasing oxygenation.82 Similarly, in 2016, Strassel et al used a simple model of successively pipetting cultured cells to introduce shear forces and produce ∼30 platelets per MK,85,97 which Pongérard et al then tripled in 2023 by combining turbulent and laminar flow in an in vitro sphere system.86 In the mid-2010s, Blin et al and Ito et al used microfluidic systems to flow MKs through coated pillar forests, thereby inducing shear stress and the production of ∼4 and 14 platelets per MK, respectively.84,83 Ito et al further showed that introducing turbulent flow into a suspension culture bioreactor increased the yield to 70 to 80 platelets per MK, and this enabled scaling of production toward clinically suitable numbers.84

Mimicking the bone marrow

In a search for increased yield and better functionality, many have attempted to mimic known in vivo processes. Notably, following the increased evidence that bone marrow sinusoids are a central zone for platelet generation, in vitro systems that attempt to simulate the interface between the marrow niche and the vasculature have been developed. Between 2013 and 2018, 3 different systems used flow and gaps in microfluidic or scaffold structures to push MKs to protrude and produce proplatelet structures. Nakagawa et al used ordered arrays of pores within a 3D scaffold87; Avanzi et al exposed MKs to increased flow, which led them to protrude through nanofiber membranes88; whereas Martinez et al trapped MKs into slits.89 These small-scale systems still showed relatively low yields that ranged from <1 to 100 platelets per MK.

To better encapsulate the physiological milieu of platelet biogenesis beyond the basic structural features of the bone marrow, the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the interplay between the vascular and osteoblastic niches need to be considered. Although the previously mentioned microfluidic systems have included thrombopoietic agents and other factors such as vWf to immobilize MKs, different combinations of shear stress, materials, and cocultures might be beneficial. For example, Thon et al designed a microfluidics system based on the dimensions of human venules in the bone marrow that is capable of integrating ECM components and vascular endothelial cells, which produced ∼30 platelets per human MK in 2014.93 This number slightly increased to >40 when primary murine MKs were used.

Others have focused on combining the characteristics of both the vascular and osteoblastic niches to drive scaffold-seeded MKs toward proplatelet protrusion into vascular-like microtubes and pores, which leads to platelet release. Starting in 2011, Pallotta et al used a 3D silk microtubular bioreactor system that lead to the production of 200 platelets per proplatelet-extending MK or an average of 14 platelets per input MK.92 Then, in 2015, Di Buduo et al described a porous silk sponge with ECM components, cytokines, and endothelium-derived proteins; however, despite successfully producing the cytoplasmic protrusions of MKs, this system only produced ∼6 platelets per seeded MK.91 Building on this, Tozzi et al improved the sponge structure in 2018 to mimic the bone marrow–vascular network interface by allowing seeded MKs to protrude into sinusoid-like channels, which generated >120 platelets per MK.90

Using animal models

Many in vitro systems are based on the assumption that MK cells and fragments need to migrate through the endothelial barrier for optimal platelet shedding before their subsequent exposure to the blood flow.98 It is uncertain if this process requires the physical forces and MK shape changes or the cell-cell and molecular interactions specific to the bone marrow and vascular environment. To advance the in vitro platelet generation field and make cost-effective transfusion units, it is critical to get a better understanding of the essential components that make platelet biogenesis so efficient in the body. The issues that are currently seen could be because these in vitro systems do not fully encapsulate the in vivo complexity of cellular interactions or oxygen concentration necessary for the efficient maturation of MKs or their release from protrusions and platelets.

Although ex vivo animal systems are predicted to be the most complete models of in vivo function, when Fujiyama et al used ex vivo porcine bone marrow to passage human MKs in 2020, this only made <5 platelets per MK.94 Thus, other organ systems, such as microvessels, have recently been investigated as potential regions of significant platelet production. Our group recently used a pulmonary-based system to generate platelets ex vivo50 in which the infusion of murine bone marrow–derived MKs into ex vivo mouse lung vasculature led to the production of ∼3000 platelets per input MK, the highest number to date by an order of magnitude. We demonstrated that mimicking the branching microvasculature structure in a microfluidic system generated ∼490 murine platelets per MK. Although significantly lower, this is still a considerable improvement over previous in vitro systems. Although these platelets showed physiological responses to agonists in vitro, they remain to be tested for in vivo functionality and life span. Furthermore, although other groups have successfully infused human MKs into murine pulmonary vasculature in vivo, future work will need to be undertaken to reproduce this ex vivo yield using human cells, an indispensable step toward medical application. Nonetheless, it remains an important advance in platelet generation outside the body and points to the importance of the vasculature for efficient platelet biogenesis.

Limitations and the field going forward

Overall, small-scale in vitro systems allow for calculated designs because the induced shear stress is easily predictable using computational fluid dynamics analysis. Notably, findings seem to indicate that flow forces alone are not enough to push MKs toward efficient platelet production, and the answer may lie in the type of shear they are subjected to (turbulent, laminar, or a combination of both) and the combination of microvasculature structures, mechanical forces, pH, and oxygenation. Although essential for discovery research, these devices are challenging to scale up and most human in vitro systems make 10× to 100× fewer platelets per MK than in vivo. Notably, to match a single apheresis donation, a platelet production system must yield 3 × 1011 functional platelets per 300 mL (or 1012 per L).99,100 When considering that hiPSC-derived MKs remain largely inefficient at thrombopoiesis and that most patients require 2 to 3 units at a time, the commercialization of current approaches faces major challenges because of the costs associated with input cells to reach the desired output.101

To date, Ito et al’s large-scale turbulent flow bioreactor remains one of the most efficient and clinically relevant systems in recent years simply because of its expansion capabilities.84 Its use in the 2022 first-in-hiPSC-derived platelets autologous transfusion study represents an important step within the field.102 Although there was a slight transient increase in D-dimer (a coagulation marker) and white blood cell count 24 hours after transfusion, it was considered safe by the Efficacy and Safety Assessment Committee. In flow cytometry analyses, larger platelets were found in the peripheral blood after transfusion, however, these gradually decreased, and the corrected count increment (evaluation of transfusion effectiveness) was not found to be increased. This could be because of the low number of cells transfused (30×, 10×, and 3× fewer cells than a typical transfusion unit), measurement timings, or an as yet unexplained increased in vivo clearance.

Overall, many challenges remain before in vitro–derived platelets can reach medical application. Although science and technology have advanced in leaps and bounds, there is now a critical need for guidelines on MK and generated platelet characterization to ensure consistency and quality across studies. Moving forward, clear and uniform accounting of the MK nature and maturity and of platelets in vitro and, when possible, in vivo functionality is paramount to ensure the development of safe products. The number of platelets generated per MK should also be clearly stated, which is unfortunately not the case currently. Standardizing reporting in the platelet generation field would ensure reproducibility and reliability of findings, thereby working toward more transparent science aimed at clinical translation. Crucially, there is bidirectional synergy between in vitro and in vivo thrombopoiesis in which furthering the knowledge of one will, in turn, improve the other. By fostering collaborations and integrating advancements in technology with understanding of platelet biology, future research has the potential for transformative progress in transfusion medicine, regenerative therapies, and in the treatment of hematological disorders.

Final perspectives

The authors believe that a large hurdle in the platelet generation field is the lack of standardized definitions and criteria for defining mature MKs, proplatelets, large protrusions, and platelets themselves. Suggestions have been made in this review (Table 1), but open discussions of these points should now be made. This would improve reproducibility and transparency in our understanding of platelet generation biology in the hope of producing efficient in vitro platelet-producing systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ingeborg Hers and Samir Taoudi (University of Bristol, United Kingdom) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Support from the Wellcome Trust (Investigator Award 219472/Z/19/Z), the British Heart Foundation (SP/F/21/150023, PG/21/10760, FS/4yPhD/F/23/34195), and the University of Bristol is gratefully acknowledged.

Authorship

Contribution: J.A.F., N.T., and A.W.P. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alastair W. Poole, School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Biomedical Sciences Building, University Walk, Bristol BS8 1TD, United Kingdom; email: a.poole@bristol.ac.uk.