Abstract

Arteriovenous-lymphatic endothelial cell fates are specified by the master regulators, namely, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1. Whereas Notch is expressed in the arteries and COUP-TFII in the veins, the lymphatics express all 3 cell fate regulators. Previous studies show that lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) fate is highly plastic and reversible, raising a new concept that all 3 endothelial cell fates may coreside in LECs and a subtle alteration can result in a reprogramming of LEC fate. We provide a molecular basis verifying this concept by identifying a cross-control mechanism among these cell fate regulators. We found that Notch signal down-regulates Prox1 and COUP-TFII through Hey1 and Hey2 and that activated Notch receptor suppresses the lymphatic phenotypes and induces the arterial cell fate. On the contrary, Prox1 and COUP-TFII attenuate vascular endothelial growth factor signaling, known to induce Notch, by repressing vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and neuropilin-1. We show that previously reported podoplanin-based LEC heterogeneity is associated with differential expression of Notch1 in human cutaneous lymphatics. We propose that the expression of the 3 cell fate regulators is controlled by an exquisite feedback mechanism working in LECs and that LEC fate is a consequence of the Prox1-directed lymphatic equilibrium among the cell fate regulators.

Introduction

The mammalian lymphatic system is derived from the blood vascular system.1,2 During early embryogenesis, a subset of venous endothelial cells expresses the homeodomain transcriptional factor Prox1 and migrates out to form the initial lymphatic vessels. These Prox1-positive migrating cells undergo lymphatic differentiation by up-regulating lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC)–specific genes and down-regulating blood vascular endothelial cell-specific genes. During the LEC differentiation process, Prox1 functions as the master regulator for lymphatic system development, and Prox1-deficient mice fail to form the lymphatic system.2

Notch receptors and ligands are known to be specifically expressed in the arterial compartment and control the arterial identity and morphogenesis during vascular development.3-7 Loss-of-function mutations of Notch result in loss of the expression of the arterial markers and up-regulation of the venous markers in the arterial compartments. Conversely, ectopic overexpression of Notch up-regulates the arterial markers in the venous compartments and suppresses the venous endothelial cell identity, perturbing the normal arteriovenous specification.8 In addition, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) acts upstream of Notch pathway for the arterial endothelial cell specification, and inhibition of VEGF interferes with normal arterial development.6,9 Therefore, VEGF and Notch pathways play a key role in formation of the arterial vessels during development.

Chicken ovalbumin upstream transcription factor (COUP-TF)–II has been known to be required to maintain the venous endothelial cell fate by suppressing the Notch signal.7,10 COUP-TFII is selectively expressed in venous, but not arterial, endothelial cells, and genetic ablation of COUP-TFII during development results in abnormal arterialization of the veins, characterized by up-regulation of the arterial markers (Notch, neuropilin-1, jag-1, Hey1, and ephrinB2) in the venous compartment.10 Notably, activated Notch, Hey1, and Hey2 have been shown to repress the promoter activity of COUP-TFII in HEK293 cells using COUP-TFII promoter reporter constructs.11 This genetic relationship suggests the presence of a negative feedback regulation between the arterialization signal (Notch) and the venous cell fate specification (COUP-TFII).

Previous studies demonstrate that LECs display remarkable cell fate plasticity. We and others reported that ectopic expression of Prox1 can reprogram vascular endothelial cells to adopt lymphatic phenotypes12,13 and that human herpesvirus-8 induces a pathologic lymphatic reprogramming of vascular endothelial cells.14-17 Moreover, it has been shown that LEC identity is reversible and ablation Prox1 resulted in dedifferentiation of LECs.18 Interestingly, whereas Notch is expressed in the arterial endothelial cells and COUP-TFII is mainly in the veins, LECs express all 3 master control genes, Notch,19 COUP-TFII,20 and Prox1.2 These findings put forward a new concept that all 3 endothelial cell identities may be coreside in LECs and that a subtle change in these cell fate regulators resulting from physiologic and pathologic stimuli can result in a dramatic reprogramming of their cell fate.

In this study, we investigated the regulatory relationship among these 3 endothelial cell fate regulators in LECs and propose a novel model that the endothelial cell fate regulators, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1, are under an exquisite feedback control mechanism and dynamically regulate each other in LECs. We hypothesize that this cross-regulation may provide the molecular basis underlying the remarkable cell fate plasticity of LECs.

Methods

Cell culture and gene expression

Human primary dermal LECs were isolated from neonatal foreskins and cultured as described.12,20 Isolation of human endothelial cells was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (Principal Ivestigator: Y.-K.H.). Transfection into endothelial cells was performed using Amaxa Systems as described.21 Vectors for human Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD),22 Hey123,24 and Hey2,25 and adenovirus for Prox1,12 COUP-TFII,20 and NICD22 were previously described. Adenovirus-expressing human Hey1 was constructed by transferring an XbaI/NotI fragment from pcDNA-hCHF2 (Dr Michael Chin, Harvard Medical School)23 into pAdTrack-CMV.26 Final construct was transfected into HEK293 cells to produce adenovirus. Adenovirus-expressing human V5-tagged NICD1 and mouse Hey2 were obtained from Dr Lucy Liaw (Maine Medical Center Research Institute).27 Plasmids expressing mouse FLAG-Hey1 (pcDNA3.1 HERP2FLAG) and mouse FLAG-Hey2 (pcDNA3.1 HERP1FLAG) were provided by Dr Laurence H. Kedes (University of Southern California).25,28 Human Hes1 adenovirus29 was provided by Dr Douglas Ball (Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions). A plasmid (pcDNA3-NICD) encoding NICD was a gift of Dr Stephen Blacklow (Harvard Medical School). Sequences of siRNA for Hey1 are listed (supplemental Figure 2, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), and those for other genes are available on request. Microarray analyses were performed using Affymetrix HG-U133A, and signal values and present/absent calls were generated using Affymetrix Microarray Analysis Suite (Version 5.0). Recombinant Jag1 and Dll4 were from R&D Systems. All microarray data have been uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus public database under accession number GSE20978.

Luciferase assay and reporter constructs

Luciferase assays were carried out in HEK293T by transfection for 48 hours in triplicates, and luciferase activity was measured using Bright-Glo reagent (Promega) and normalized by total protein amount. Luciferase reporter constructs harboring a 10-kb murine COUP-TFII promoter (pCoupTFIIA)11 were obtained from Dr Manfred Gessler (University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg, Germany) and its derivatives were generated as follows: pCoupTFIIA was digested by NheI, KpnI/HindIII, and KpnI/EcoRI and self-ligated to make pCoupTFIIB (−5.5 kb), pCouTFIIC (−3.2 kb), and pCouTFIID (−2.0 kb), respectively. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) promoter constructs30 were provided by Dr Stephen Safe (Texas A&M University). Luciferase constructs harboring a 0.9-kb human neuropilin-1 (NP-1) promoter31 or a 5-kb mouse NP-1 promoter32 were generous gifts from Drs Michael Klagsbrun (Harvard Medical School) and Achim Gossler (Institute for Molecular Biology, Hannover, Germany), respectively.

Western blot and immunostaining analyses

Western blot analyses were carried out as described.12 Sources of the antibodies are Prox1 (Chemicon), LYVE-1 (Upstate Biotechnology), VEGFR-3 (eBioscience), human podoplanin (D2-40, Covance), COUP-TFII (R&D Systems), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); VEGFR-2, NP-1 (C-19), Np-2, Notch-1, and p27Kip1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); phosphor-VEGFR-2 (Tyr1175; Cell Signaling Technology), and Ephrin B2 and ephB4 (Dr Parkash Gill, University of Southern California). Immunostainings were performed on frozen human foreskin sections as described12 using antibodies against human podoplanin (Covance), Prox1 and LYVE-1 (ReliaTech), and Notch1 and Notch4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

EMSA

Electromobility shift assays (EMSA) was performed as described33 with bacterially produced recombinant full-length human Prox1 and COUP-TFII proteins. Human Prox1 cDNA was cloned into BamHI/EcoRI site of pRSET B (Invitrogen). GST-COUP-TFII expression vector34 was a gift from Dr Tomoshige Kino (National Institutes of Health). His-tagged Prox1 and GST-COUP-TFII recombinant proteins were overexpressed in BL21(DE3)pLysS (Promega). To make the EMSA probes, oligonucleotides for human VEGFR2 promoter (CCGCACGGGAGAGCCCCTCCTCCGCTCCGG, CGGGGCGGGGCCGGAGCGGAGGAGGGGCTC) were annealed and extended by Klenow in the presence of [32P] dCTP. Protein/DNA binding reaction was performed by incubating 32P-labeled DNA (50 000 cpm) and fusion proteins (0.2 μg) in a buffer (20mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.9, 0.5mM dithiothreitol, 0.1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 150mM KCl, 15% glycerol, 0.3 μg of poly[dI-dC]) at 25°C for 20 minutes and then subjected to 8% polyacrylamide electrophoresis in Tris-borate/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed as published.35 Briefly, chromatins of cell lysate of LECs were sheared by sonication and precleared. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-Prox1, rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti–COUP-TFII or mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies at 4°C overnight. Precipitated genomic DNA was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a set of primers for human VEGFR2 promoter (AGATTCTCGGCCACTTCAGA, CCAGGAGAGAACATCCCAGA) and human NP-1 promoter (CCAAATCTCGGGAAACAATG, AGTGTCGCTGTGGTGTGAAG).

Results

Notch signaling down-regulates Prox1 expression

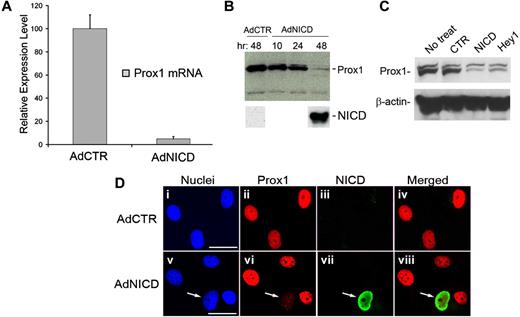

To investigate the effect of Notch signaling in LECs, we performed a series of in vitro analyses using primary LECs isolated from human foreskins. We adenovirally expressed human NICD, a constitutively active form of Notch1 receptor,22 in primary LECs and found that NICD strongly repressed the steady-state level of Prox1 mRNA within 48 hours (Figure 1A). We also confirmed decreased Prox1 protein expression in primary LECs by NICD using Western blot analyses (Figure 1B). To avoid a possible artifact that could result from adenovirus infection, we transiently transfected a nonviral plasmid vector for NICD into primary LECs and verified the NICD-mediated repression of Prox1 protein (Figure 1C). Because cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β, have been shown to repress Prox1 expression in LECs,36 we asked whether the NICD-mediated repression of Prox1 can be caused through a paracrine effect induced by diffusible factor(s) that may be released from neighboring NICD-overexpressing cells. To address this question, we transduced LECs with adenovirus expressing a V5-tagged NICD for 48 hours and performed immunofluorescent analysis for Prox1 and the V5 tag. Notably, Prox1 down-regulation was observed only in NICD-expressing LECs, but not in closely neighboring cells (Figure 1D arrow). Taken together, our data demonstrate that Notch down-regulates Prox1 expression in primary LECs and that this down-regulation of Prox1 is not the result of a paracrine effect.

Activated Notch receptor represses Prox1 expression. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR study shows that adenoviral expression of human NICD in primary human LECs for 48 hours significantly reduced the level of Prox1 mRNA. AdCTR indicates control adenovirus; and AdNICD, NICD-expressing adenovirus. Data are mean plus or minus SD relative to the value of AdCTR. (B) Western blot assay demonstrates a gradual reduction of Prox1 protein level after adenoviral transduction of LECs with NICD at 10, 24, and 48 hours. (C) Western blot assay shows that transient transfection of primary human LECs with a control plasmid vector (CTR, pcDNA3), NICD (pcDNA3-NICD), or Hey1-expressing (pcDNA-hCHF2) plasmids for 48 hours resulted in a significant reduction in the Prox1 protein level. (D) Immunofluorescence analyses of primary LECs that were transduced with either a control (AdCTR, i-iv) or V5-tagged human NICD-expressing (AdNICD, v-viii) adenovirus for 48 hours against nuclei (i,v), Prox1 (ii,vi), V5-tag NICD (iii,vii), and merged images (iv,viii). Arrows in images v to viii point to an LEC with down-regulated Prox1 expression resulting from NICD expression, demonstrating an autonomous regulation of Prox1 by Notch. Bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope with a 63× objective and processed with AxioVision Digital Imaging software.

Activated Notch receptor represses Prox1 expression. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR study shows that adenoviral expression of human NICD in primary human LECs for 48 hours significantly reduced the level of Prox1 mRNA. AdCTR indicates control adenovirus; and AdNICD, NICD-expressing adenovirus. Data are mean plus or minus SD relative to the value of AdCTR. (B) Western blot assay demonstrates a gradual reduction of Prox1 protein level after adenoviral transduction of LECs with NICD at 10, 24, and 48 hours. (C) Western blot assay shows that transient transfection of primary human LECs with a control plasmid vector (CTR, pcDNA3), NICD (pcDNA3-NICD), or Hey1-expressing (pcDNA-hCHF2) plasmids for 48 hours resulted in a significant reduction in the Prox1 protein level. (D) Immunofluorescence analyses of primary LECs that were transduced with either a control (AdCTR, i-iv) or V5-tagged human NICD-expressing (AdNICD, v-viii) adenovirus for 48 hours against nuclei (i,v), Prox1 (ii,vi), V5-tag NICD (iii,vii), and merged images (iv,viii). Arrows in images v to viii point to an LEC with down-regulated Prox1 expression resulting from NICD expression, demonstrating an autonomous regulation of Prox1 by Notch. Bars represent 50 μm. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope with a 63× objective and processed with AxioVision Digital Imaging software.

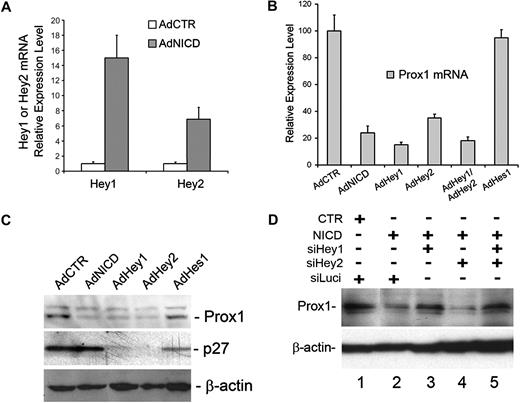

Down-regulation of Prox1 by activated Notch is mediated by Hey1

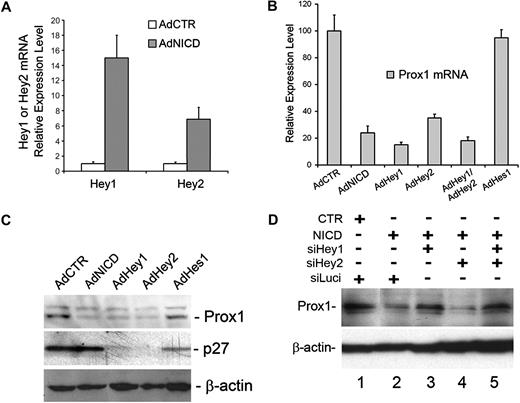

We next investigated the modulation of global transcriptional profiles by NICD in primary LECs, which were transduced for 10 or 24 hours with either a control or NICD adenovirus using microarray analyses. Notably, our microarray study again confirmed the NICD-mediated Prox1 down-regulation (Table 1). We then found that Hey1 and Hey 2, among many Notch downstream effectors tested, were most prominently up-regulated in NICD-overexpressed LECs at both time points (Table 1). We verified the NICD-induced up-regulation of Hey1 and Hey2 in LECs using quantitative real-time reverse-transcribed (RT)–PCR (Figure 2A). We next asked whether Notch effector proteins can repress Prox1 expression and thus adenovirally expressed Hey1, Hey2, and Hes1 in primary LECs. Indeed, adenoviral expression of NICD, Hey1, or Hey2 in primary LECs showed a strong repression of Prox1 mRNA expression (Figure 2B). Coexpression of Hey1 and Hey2 did not show either additive or synergistic repression, suggesting that the 2 proteins may redundantly function in regulating Prox1 expression. In an interesting comparison, Hes1 was unable to repress Prox1 expression in LECs. Consistently, Prox1 protein expression was also significantly reduced by adenoviral expression of NICD, Hey1, or Hey2 (Figure 2C) and by transient transfection of a plasmid vector expressing Hey1 (Figure 1C). Again, Hes1 did not repress Prox1 protein expression in LECs, although Hes1 significantly repressed its known target gene p27Kip137 (Figure 2C). Notably, although p27Kip1 was not regulated by NICD, it was significantly repressed by Hey1 and Hey2, suggesting that Notch receptor and its effectors differentially regulate p27Kip1 in LECs (Figure 2C). We next asked whether Hey1 and/or Hey2 are required for NICD-mediated Prox1 repression and performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of Hey1 and/or Hey2 in the presence of NICD in primary LECs. We found that, whereas Hey2 knockdown alone did not affect the NICD-mediated Prox1 repression, Hey1 single knockdown and Hey1/2 double knockdown significantly abrogated the NICD-mediated Prox1 repression (Figure 2D). Interestingly, we found that Hey1 single knockdown resulted in down-regulation of not only Hey1, but also Hey2 (supplemental Figure 1). This unexpected down-regulation of Hey2 by Hey1 knockdown in LECs was further confirmed using 4 different Hey1 siRNA duplexes, of which sequences are significantly different from that of Hey2 mRNA, thus excluding a possibility of Hey1 siRNA cross-targeting Hey2 mRNA (supplemental Figures 2-4). The molecular mechanism underlying this regulation remains to be investigated. Together, our data indicate that Prox1 is a target gene of Hey1 and Hey2 and that activated Notch receptor represses Prox1 through these 2 effector proteins.

Activated Notch receptor down-regulates Prox1 through Hey proteins. (A) Expression of Hey1 and Hey2 was determined by quantitative RT-PCR in LECs that were transduced with a control or NICD-expressing adenovirus for 48 hours. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR assay showing the repression of Prox1 mRNA in primary human LECs by adenoviral expression of NICD (AdNICD), Hey1 (AdHey1), Hey2 (AdHey2), Hey1 and Hey2 (AdHey1/AdHey2), and Hes1 (AdHes1) for 48 hours. (C) Expression of Prox1 and p27Kip1 proteins was determined by Western blot analyses in primary LECs that were transduced with AdCTR, AdNICD, AdHey1, or AdHes1 for 48 hours. (D) The expression of Prox1 protein after cotransfection of LECs with a control (CTR) or NICD-expressing plasmid vector along with siRNA duplexes for the firefly luciferase (siLuci), Hey1 (siHey1), and Hey2 (siHey2) for 48 hours. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of AdCTR.

Activated Notch receptor down-regulates Prox1 through Hey proteins. (A) Expression of Hey1 and Hey2 was determined by quantitative RT-PCR in LECs that were transduced with a control or NICD-expressing adenovirus for 48 hours. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR assay showing the repression of Prox1 mRNA in primary human LECs by adenoviral expression of NICD (AdNICD), Hey1 (AdHey1), Hey2 (AdHey2), Hey1 and Hey2 (AdHey1/AdHey2), and Hes1 (AdHes1) for 48 hours. (C) Expression of Prox1 and p27Kip1 proteins was determined by Western blot analyses in primary LECs that were transduced with AdCTR, AdNICD, AdHey1, or AdHes1 for 48 hours. (D) The expression of Prox1 protein after cotransfection of LECs with a control (CTR) or NICD-expressing plasmid vector along with siRNA duplexes for the firefly luciferase (siLuci), Hey1 (siHey1), and Hey2 (siHey2) for 48 hours. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of AdCTR.

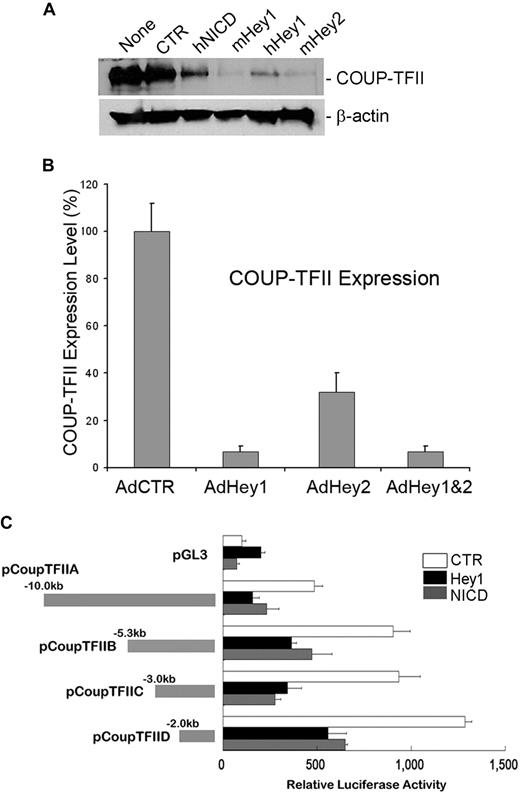

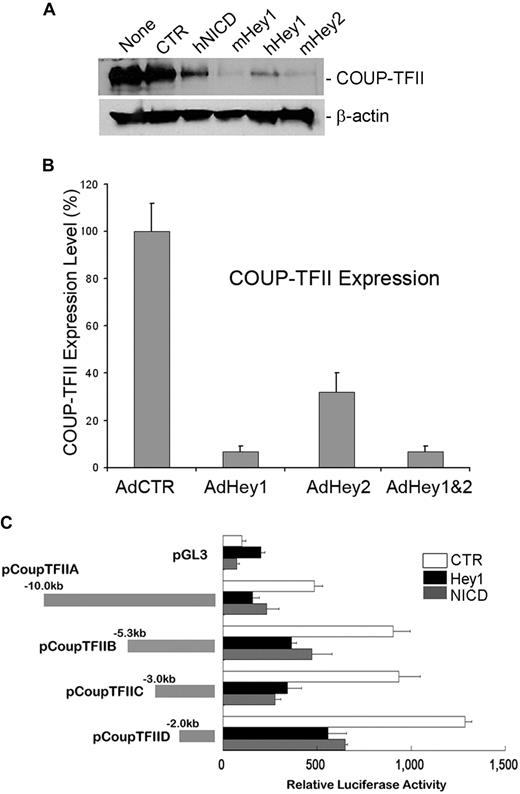

Notch signal proteins down-regulate COUP-TFII in LECs

We and others have recently reported that Prox1 physically and functionally interacts with the orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII to specify the lymphatic cell fate.20,38 Because our current study revealed that Notch protein represses Prox1 expression in LECs, we next asked whether Notch also regulates COUP-TFII in LECs. To address this question, we transiently transfected various NICD-, Hey1-, and Hey2-expressing plasmid vectors into human primary LECs and determined the level of COUP-TFII protein by Western blot analyses. Indeed, COUP-TFII was significantly down-regulated by NICD, Hey1, and Hey2 (Figure 3A). We then asked whether this Notch-mediated COUP-TFII repression occurs at the mRNA level by determining the COUP-TFII mRNA expression in LECs transduced by Hey1 and/or Hey2 adenovirus and found that Hey1 and Hey2 could repress the expression of COUP-TFII mRNA (Figure 3B). Because multiple mechanisms have been proposed for Hey1/Hey2-mediated gene regulation,39 we next asked whether NICD and Hey1 regulate the COUP-TFII promoter for the repression and investigated the response of the COUP-TFII promoter to NICD and Hey1 using a series of COUP-TFII promoter reporter constructs. We found that a 2-kb proximal promoter of COUP-TFII is sufficient to respond to NICD and Hey1-mediated repression (Figure 3C). Taken together, our data demonstrate that Notch pathway proteins (Notch receptor, Hey1, and Hey2) repress the expression of COUP-TFII by regulating its promoter activity.

Down-regulation of COUP-TFII by Notch pathway proteins in LECs. (A) Expression of COUP-TFII protein in LECs that were transiently transfected with a control vector (CTR, pcDNA3) or vectors expressing human NICD (hNICD, pcDNA3-hNICD), mouse Hey1 (mHey1, pcDNA3.1 HERP2FLAG), human Hey1 (hHey1, pcDNA-hCHF2), or mouse Hey2 (mHey2, pcDNA3.1 HERP1FLAG). None indicates untransfected LECs. (B) Expression of COUP-TFII mRNA was determined by quantitative RT-PCR in LECs that were transduced with a control (AdCTR), Hey1 (AdHey1), and/or Hey2 (AdHey2) adenovirus after 48 hours. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of AdCTR. (C) Repression of COUP-TFII promoter activity by human NICD and Hey1. Mouse COUP-TFII promoter luciferase constructs were cotransfected with a control (CTR), Hey1, or NICD vector into HEK293 cells for 48 hours, and the promoter activity was determined by luciferase activity that was normalized with the amount of whole cell lysate used. pGL3 indicates pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). Data are relative luciferase activity ± SD.

Down-regulation of COUP-TFII by Notch pathway proteins in LECs. (A) Expression of COUP-TFII protein in LECs that were transiently transfected with a control vector (CTR, pcDNA3) or vectors expressing human NICD (hNICD, pcDNA3-hNICD), mouse Hey1 (mHey1, pcDNA3.1 HERP2FLAG), human Hey1 (hHey1, pcDNA-hCHF2), or mouse Hey2 (mHey2, pcDNA3.1 HERP1FLAG). None indicates untransfected LECs. (B) Expression of COUP-TFII mRNA was determined by quantitative RT-PCR in LECs that were transduced with a control (AdCTR), Hey1 (AdHey1), and/or Hey2 (AdHey2) adenovirus after 48 hours. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of AdCTR. (C) Repression of COUP-TFII promoter activity by human NICD and Hey1. Mouse COUP-TFII promoter luciferase constructs were cotransfected with a control (CTR), Hey1, or NICD vector into HEK293 cells for 48 hours, and the promoter activity was determined by luciferase activity that was normalized with the amount of whole cell lysate used. pGL3 indicates pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). Data are relative luciferase activity ± SD.

Notch ligands, Jag-1 and Dll4, repress Prox1 and COUP-TFII in LECs

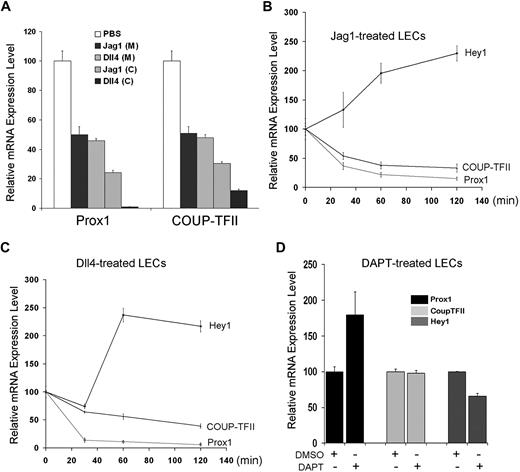

Our data above (Figures 1,Figure 2–3) demonstrated that activated Notch receptor can repress Prox1 and COUP-TFII expression. We then asked whether activation of LECs by Notch ligands would recapitulate the same regulation and treated LECs with soluble Jag1 and Dll4 recombinant proteins. Soluble Jag1 or Dll4 recombinant protein was either directly added in culture media of LECs or precoated on the culture plates before seeding of LECs. We found that both approaches resulted in down-regulation of Prox1 and COUP-TFII in LECs (Figure 4A). Moreover, we studied the dynamics of this regulation by measuring the early response of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII gene expression on addition of soluble Jag1 or Dll4 recombinant protein in culture media of primary LECs. Notably, within 60 minutes, both Notch ligands could activate Hey1 expression and repress the expression of Prox1 and COUP-TFII in LECs (Figure 4B-C). In addition, to assess whether Notch pathway is active in isolated and cultured LECs, we inhibited Notch receptor with DAPT and determined the expression of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII. Notably, Notch inhibition in LECs resulted in only marginal alteration in the expression of Hey1 and Prox1 and no change in COUP-TFII expression (Figure 4D), suggesting that, at least under our in vitro culture condition, Notch pathway may be not significantly active in LECs and/or inhibition of Notch pathway is not sufficient to further induce Prox1 expression. Taken together, these data demonstrate that, consistent with Prox1/COUP-TFII regulation by activated Notch receptor (NICD), Notch ligands can also repress the expression of Prox1 and COUP-TFII in postdevelopmental LECs.

Regulation of Prox1 and COUP-TFII by Notch ligands. (A) Notch ligands, Jag1 and Dll4, down-regulate Prox1 and COUP-TFII in primary LECs. Soluble Jag1 or Dll4 recombinant protein was either added to culture media (200 ng/mL) of LECs or precoated (1 μg/mL) on culture dishes before LEC culturing. After 24-hour activation by the soluble ligands in media (M) or 48-hour activation by precoated ligands (C), LECs were harvested for quantification of the expression of Prox1 and COUP-TFII. (B-C) Early response in the expression of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII in LECs by soluble Notch ligands. Soluble Jag1 (100 ng/mL; B) or Dll4 (100 ng/mL; C) was added in LEC-culture media, and total RNA was harvested after 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes for quantitative RT-PCR analyses. (D) Regulation of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII in LECs on inhibition of Notch signal pathway. LECs were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) or Notch inhibitor DAPT (60 nM), and total RNA was harvested after 24 hours for quantitative RT-PCR analyses. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) treatment (A), 0-hour time point (B-C), or DMSO treatment (D).

Regulation of Prox1 and COUP-TFII by Notch ligands. (A) Notch ligands, Jag1 and Dll4, down-regulate Prox1 and COUP-TFII in primary LECs. Soluble Jag1 or Dll4 recombinant protein was either added to culture media (200 ng/mL) of LECs or precoated (1 μg/mL) on culture dishes before LEC culturing. After 24-hour activation by the soluble ligands in media (M) or 48-hour activation by precoated ligands (C), LECs were harvested for quantification of the expression of Prox1 and COUP-TFII. (B-C) Early response in the expression of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII in LECs by soluble Notch ligands. Soluble Jag1 (100 ng/mL; B) or Dll4 (100 ng/mL; C) was added in LEC-culture media, and total RNA was harvested after 0, 30, 60, and 120 minutes for quantitative RT-PCR analyses. (D) Regulation of Hey1, Prox1, and COUP-TFII in LECs on inhibition of Notch signal pathway. LECs were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) or Notch inhibitor DAPT (60 nM), and total RNA was harvested after 24 hours for quantitative RT-PCR analyses. Data are mean ± SD relative to the value of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) treatment (A), 0-hour time point (B-C), or DMSO treatment (D).

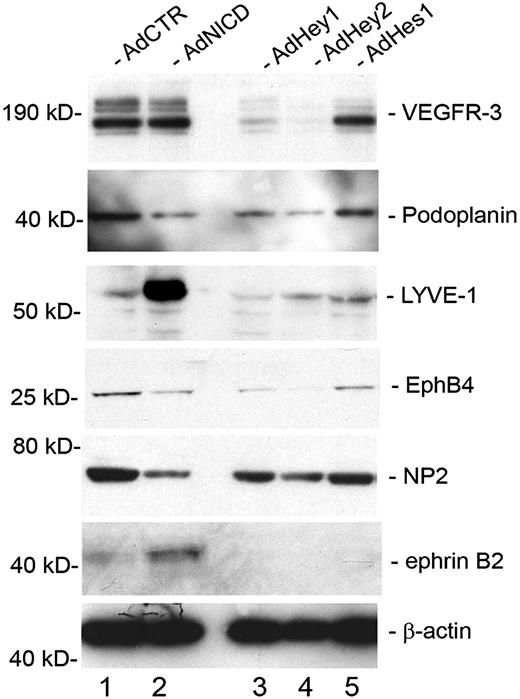

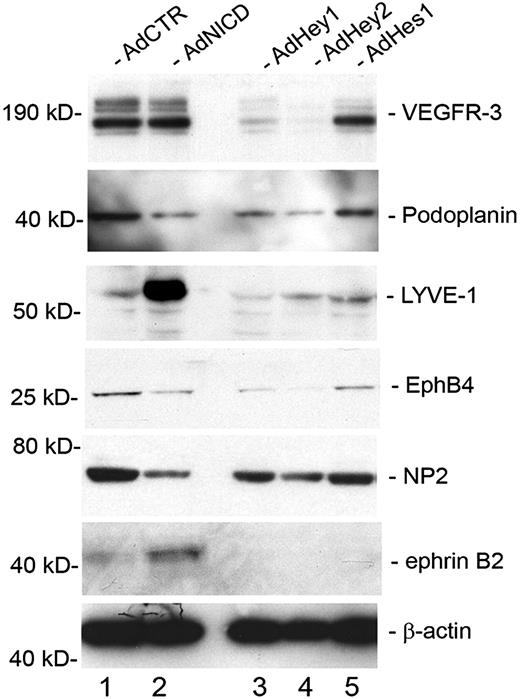

Notch signal regulates other lymphatic markers

We next asked whether Notch and its downstream effectors (Hey1, Hey2, and Hes1) can regulate other endothelial-lineage genes, in addition to Prox1 and COUP-TFII, in LECs. Activated Notch receptor has been previously shown to induce the expression of the lymphatic-specific gene VEGFR-3 in blood vascular endothelial cells.19 In an interesting comparison, overexpression of activated Notch in primary LECs did not induce an additional up-regulation of VEGFR-3 (Figure 5). We hypothesize that VEGFR-3 is already highly expressed in LECs, and an additional activation signal by NICD may not further increase the expression of VEGFR-3. More notably, however, we found that VEGFR-3 was significantly down-regulated by Hey1 and Hey2, but not significantly by Hes1. Another lymphatic marker podoplanin was down-regulated by NICD, Hey1, and Hey2, but not by Hes1. In contrast, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1 was strongly up-regulated by NICD but down-regulated by Hey1 and Hey2. Moreover, EphB4 and NP-2, which are known to be expressed in the veins and certain lymphatics,40,41 were down-regulated by NICD, Hey1, and Hey2, but not by Hes1. Finally, the arterial marker ephrinB2 was up-regulated only by NICD, but not by Hey1, Hey2, or Hes1. We also found that activated NICD strongly down-regulated a number of other previously reported lymphatic markers, including coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor,42,43 c-Maf,14,44 plakoglobin,13 transforming growth factor-α,14 aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 A1,14 and growth hormone receptor14,45 (Table 2). Taken together, these data indicate that Notch signal suppresses the lymphatic phenotypes and possibly augments the arterial phenotype in postdevelopmental LECs.

Regulation of lineage-specific gene expression by Notch signal proteins in primary LECs. Western blot analyses showing the expression of vascular markers for lymphatic (VEGFR-3, podoplanin, LYVE-1), venous (EphB4, NP-2), and arterial (ephrinB2) endothelial cells in primary LECs that were transduced with a control (AdCTR), NICD (AdNICD), Hey1 (AdHey1), Hey2 (AdHey2), or Hes1 (AdHes1)–expressing adenovirus for 48 hours.

Regulation of lineage-specific gene expression by Notch signal proteins in primary LECs. Western blot analyses showing the expression of vascular markers for lymphatic (VEGFR-3, podoplanin, LYVE-1), venous (EphB4, NP-2), and arterial (ephrinB2) endothelial cells in primary LECs that were transduced with a control (AdCTR), NICD (AdNICD), Hey1 (AdHey1), Hey2 (AdHey2), or Hes1 (AdHes1)–expressing adenovirus for 48 hours.

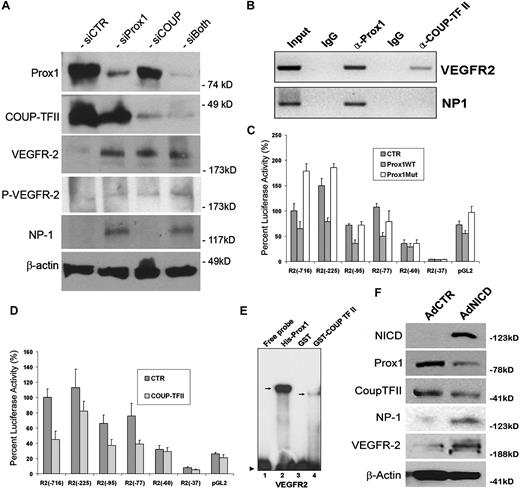

Regulation of VEGF signaling in LECs by Prox1 and COUP-TFII

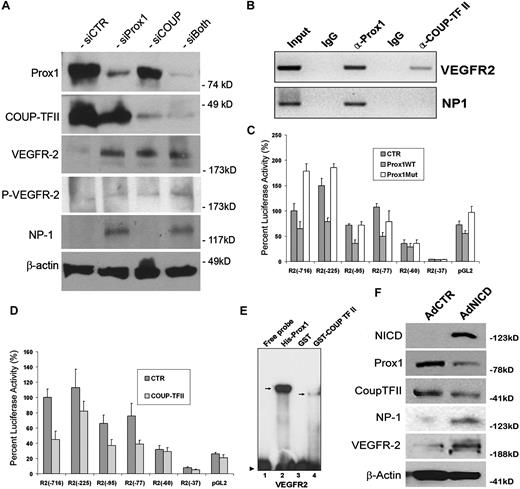

Previous studies have shown that VEGF acts upstream of Notch pathway for the arterial differentiation6 and that a local concentration of VEGF appears to determine the arteriovenous endothelial cell fate,46,47 suggesting that VEGF and Notch function as the major endothelial cell-fate regulating pathways in vasculogenesis. Our data above (Figures 1,Figure 2–3) demonstrated that Notch signal down-regulates 2 key lymphatic cell fate regulators, Prox1 and COUP-TFII, suggesting that the arterial signal may suppress a developmental program specifying for lymphatic differentiation. Therefore, we next set out to investigate the effect of Prox1 and COUP-TFII in regulation of VEGF signal in cultured LECs by inhibiting Prox1 and/or COUP-TFII in LECs using siRNA. We found that Prox1 knockdown in LECs induced the expressions of VEGFR-2 and its coreceptor NP-1, and phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 (Figure 6A). COUP-TFII knockdown resulted in increased expression and phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 but did not induce NP-1 expression in LECs. This finding is notable because NP-1 was shown to be up-regulated when COUP-TFII was ablated in venous endothelial cells in vivo.10 We hypothesize that this cell type-specific differential regulation of NP-1 by COUP-TFII is the result of the presence of Prox1, which can still repress NP-1 in LECs, even when functional COUP-TFII is deficient. Double knockdown of Prox1 and COUP-TFII caused a moderate up-regulation in the expression and phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 (Figure 6A). These data indicate that Prox1 and COUP-TFII suppress VEGF signaling by down-regulating its receptors, VEGFR-2 and NP-1, in LECs.

Control of VEGF signaling by LEC-fate regulators, Prox1 and COUP-TFII. (A) Western blot analyses show that knockdown of Prox1 and/or COUP-TFII up-regulates the expression of VEGFR-2 and/or NP-1 and activates phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 (Y1175). (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrate that, although Prox1 protein is associated with the proximal promoters of VEGFR-2 and NP-1, COUP-TFII protein is associated only with the VEGFR-2 promoter. (C-D) Repression of the VEGFR-2 proximal promoter by Prox1 (C) or COUP-TFII (D). A series of VEGFR-2 promoter constructs was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells for 48 hours with a control (CTR), wild-type Prox1 (Prox1WT), or DNA-binding mutant (Prox1Mut) vector. Each number (eg, −716) represents the distal end of human VEGFR-2 promoters, and all of them end at +268.30 Only 10% of luciferase activity was charted for pGL2 (pGL2-Basic vector) because of low activities of VEGFR-2 promoters. Data are relative luciferase activity ± SD. (E) Prox1 and COUP-TFII recombinant proteins bind to the VEGFR-2 proximal promoter. EMSA was performed against a DNA probe with sequences between −90 and −51 nucleotides of human VEGFR-2 promoter30 using recombinant His-Prox1, GST, or GST-COUP-TFII protein. (F) Up-regulation of NP-1 and VEGFR-2 by activated Notch receptor in LECs. Western blot analyses show the Notch-mediated regulation of Prox1, COUP-TFII, NP-1, and VEGFR-2.

Control of VEGF signaling by LEC-fate regulators, Prox1 and COUP-TFII. (A) Western blot analyses show that knockdown of Prox1 and/or COUP-TFII up-regulates the expression of VEGFR-2 and/or NP-1 and activates phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 (Y1175). (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrate that, although Prox1 protein is associated with the proximal promoters of VEGFR-2 and NP-1, COUP-TFII protein is associated only with the VEGFR-2 promoter. (C-D) Repression of the VEGFR-2 proximal promoter by Prox1 (C) or COUP-TFII (D). A series of VEGFR-2 promoter constructs was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells for 48 hours with a control (CTR), wild-type Prox1 (Prox1WT), or DNA-binding mutant (Prox1Mut) vector. Each number (eg, −716) represents the distal end of human VEGFR-2 promoters, and all of them end at +268.30 Only 10% of luciferase activity was charted for pGL2 (pGL2-Basic vector) because of low activities of VEGFR-2 promoters. Data are relative luciferase activity ± SD. (E) Prox1 and COUP-TFII recombinant proteins bind to the VEGFR-2 proximal promoter. EMSA was performed against a DNA probe with sequences between −90 and −51 nucleotides of human VEGFR-2 promoter30 using recombinant His-Prox1, GST, or GST-COUP-TFII protein. (F) Up-regulation of NP-1 and VEGFR-2 by activated Notch receptor in LECs. Western blot analyses show the Notch-mediated regulation of Prox1, COUP-TFII, NP-1, and VEGFR-2.

To further corroborate these findings, we asked whether Prox1 and/or COUP-TFII proteins are physically associated with the promoter regions of VEGFR-2 and/or NP-1 and performed chromatin immunoprecipitation against Prox1 and COUP-TFII proteins in human primary LECs. Indeed, Prox1 was found to be associated with the VEGFR-2 and NP-1 promoters (Figure 6B). In comparison, COUP-TFII protein was associated with the promoter of VEGFR-2 but not NP-1. These data are consistent with our findings that, whereas Prox1 knockdown up-regulated VEGFR-2 and NP-1, COUP-TFII knockdown activated the expression of VEGFR-2, not NP-1, in LECs (Figure 6A).

Moreover, we asked whether the Prox1 and COUP-TFII–mediated regulations occur at the transcriptional level and studied the promoters of VEGFR-2 and NP-1 using the promoter-reporter constructs of VEGFR-2 and NP-1. Report assays using a series of promoter deletion constructs showed that the proximal promoter of VEGFR-230 can be repressed by wild-type Prox1 protein, but not by a DNA-binding defective mutant Prox1 protein,33 and that a proximal promoter fragment spanning from −77 to +268 nucleotides30 was sufficient to deliver the Prox1-mediated repression (Figure 6C). Similarly, we studied the regulation of the VEGFR-2 promoter by COUP-TFII and observed a comparable pattern of VEGFR-2 promoter repression by COUP-TFII: a proximal promoter spanning from −77 to +268 nucleotides30 was sufficient to deliver the COUP-TFII–mediated repression (Figure 6D). For both cases, a shorter VEGFR-2 promoter (−60 to +268 nucleotides30 ) was not able to deliver their repression (Figure 6C-D), indicating the presence of cis-elements for Prox1 and COUP-TFII between −77 to −60 nucleotides of the VEGFR-2 promoter. Consistent with the results from double-knockdown study (Figure 6A), coexpression of Prox1 and COUP-TFII did not yield a significant additive or synergistic repression of the VEGFR-2 promoter activity (data not shown).

We then asked whether Prox1 and COUP-TFII proteins can bind to the putative cis-elements that may reside between −77 and −60 nucleotides of the VEGFR-2 promoter and performed EMSA using purified Prox1 and COUP-TFII recombinant proteins and DNA oligonucleotides harboring DNA sequences between −77 to −60 nucleotides of the VEGFR-2 promoter. Our EMSA study revealed that Prox1 and COUP-TFII protein indeed bind to the cis-elements of the VEGFR-2 promoter and that Prox1 shows a much higher affinity than COUP-TFII (Figure 6E). We also performed NP-1 promoter reporter assays using 2 previously characterized proximal promoters of NP-1: 0.9-kb31 and 5-kb32 promoter constructs. We found that neither of the reporter constructs was responsive to the Prox1-mediated repression (supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that additional regulatory elements may be necessary for the Prox1-mediated regulation of NP-1.

In addition, because Prox1 and COUP-TFII knockdown resulted in down-regulation of NP-1 and VEGFR-2, we asked whether activated Notch can up-regulate NP-1 and VEGFR-2. Indeed, we found that adenoviral ectopic expression of NICD significantly up-regulated NP-1 and VEGFR-2 (Figure 6F). Taken all together, our data indicate that Prox1 and COUP-TFII suppress the VEGF signaling in LECs by down-regulating the VEGF receptors, VEGFR-2 and NP-1.

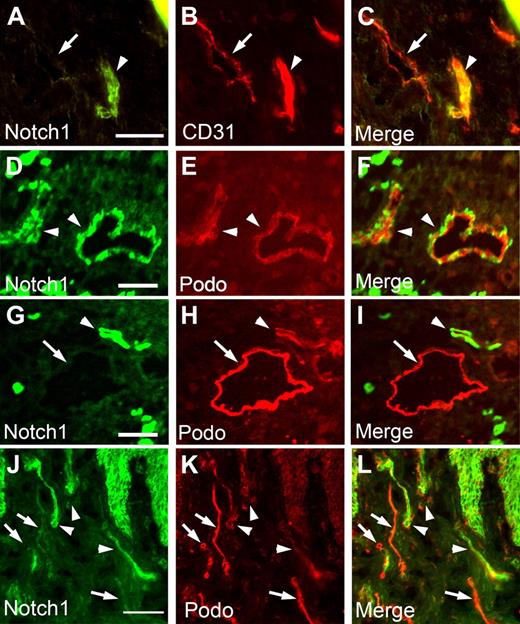

Podoplanin-based lymphatic heterogeneity is associated with differential expression of Notch

Wick et al48 have recently reported 2 subsets of lymphatic vessels with different expression levels of podoplanin and accordingly termed LECpodo-high versus LECpodo-low. Importantly, they display different characteristics in immune cell trafficking and cytokine productions, such as CCL21.48 Because our data showed that podoplanin is down-regulated by activated Notch, Hey1, and Hey2 in LECs (Figure 5), we asked whether the differential expression of podoplanin in these 2 distinct lymphatic subpopulations is associated with differential expression of Notch. We thus performed immunofluorescent studies of human neonatal foreskins with antipodoplanin and anti-Notch1 antibodies. Indeed, we found that most podoplanin-low lymphatic vessels (LECpodo-low) expressed a high level of Notch1 and, reciprocally, podoplanin-high lymphatic vessels (LECpodo-high) showed only a low expression of Notch (Figure 7). Moreover, our study revealed that activated Notch receptor significantly suppresses the expression of CCL21 (Table 2), consistent with the previous report48 that CCL21 is down-regulated in the podo-low lymphatics, compared with the podo-high lymphatic vessels. Together, our findings demonstrate that Notch signal may play an important role in specification of LECpodo-high and LECpodo-low subpopulations during lymphatic development.

Inverse correlation between the expressions of Notch receptor and podoplanin in postdevelopmental human cutaneous lymphatics. Human neonatal foreskin sections were stained for Notch1 (A,D,G,J) and CD31 (B) or podoplanin (E,H,K). Merged images are shown (C,F,I,L). (A-C) Arrowhead indicates a CD31-high, Notch-high blood vessel, and arrow points to a CD31-low, Notch-low lymphatic vessel. (D-L) All arrowheads mark Notch-high, podoplanin-low lymphatic vessels, and all arrows indicate Notch-low, podoplanin-high lymphatic vessels. Note the inverse correlation in the expression levels of Notch versus podoplanin in panels I and L. Bars represent 100 μm. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope with a 63× objective and processed with AxioVision Digital Imaging software.

Inverse correlation between the expressions of Notch receptor and podoplanin in postdevelopmental human cutaneous lymphatics. Human neonatal foreskin sections were stained for Notch1 (A,D,G,J) and CD31 (B) or podoplanin (E,H,K). Merged images are shown (C,F,I,L). (A-C) Arrowhead indicates a CD31-high, Notch-high blood vessel, and arrow points to a CD31-low, Notch-low lymphatic vessel. (D-L) All arrowheads mark Notch-high, podoplanin-low lymphatic vessels, and all arrows indicate Notch-low, podoplanin-high lymphatic vessels. Note the inverse correlation in the expression levels of Notch versus podoplanin in panels I and L. Bars represent 100 μm. Fluorescent images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope with a 63× objective and processed with AxioVision Digital Imaging software.

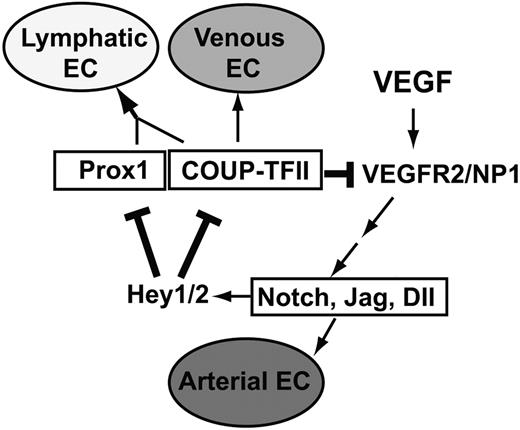

A feedback regulatory mechanism for the endothelial cell fate regulators in LECs

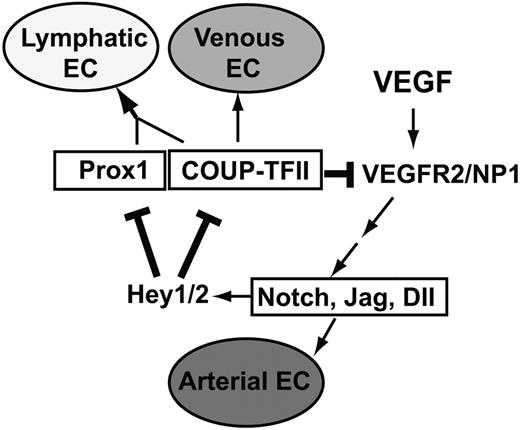

Our findings in this study enable us to add 2 new regulatory components in a previously proposed model of endothelial cell fate regulation7,10 (Figure 8). Addition of these new regulatory components establishes a novel feedback mechanism, which allows a cross-regulation among the cell fate regulators Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1. In this mechanism, whereas Notch signal represses the expression of Prox1 and its interacting partner COUP-TFII through Hey1 and Hey2, Prox1 and COUP-TFII repress NP-1 and VEGFR-2 and attenuate VEGF activity, which is known to induce Notch pathway. Together, we built a model of an exquisite cross-regulation among the cell fate controllers for the arterial (Notch), venous (COUP-TFII), and lymphatic (Prox1) endothelial cells. We propose that this cross-regulation mechanism plays an important role in LEC-fate specification and the remarkable plasticity of LECs.

Our working model of an exquisite negative feedback control mechanism among the major cell fate regulators, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1. Our data presented in this study allow us to add 2 new regulatory components (bolded lines) to the previously proposed model7,10 for endothelial cell fate specification. VEGF acts upstream of Notch, which regulates the arterial endothelial cell (EC) fate, and COUP-TFII governs venous EC fate. Prox1 interacts with COUP-TFII to specify LEC fate. Hey1 and Hey2 (Hey1/2) suppress Prox1 and COUP-TFII, which down-regulate VEGF receptors, VEGFR-2 and NP-1, to control VEGF activity.

Our working model of an exquisite negative feedback control mechanism among the major cell fate regulators, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1. Our data presented in this study allow us to add 2 new regulatory components (bolded lines) to the previously proposed model7,10 for endothelial cell fate specification. VEGF acts upstream of Notch, which regulates the arterial endothelial cell (EC) fate, and COUP-TFII governs venous EC fate. Prox1 interacts with COUP-TFII to specify LEC fate. Hey1 and Hey2 (Hey1/2) suppress Prox1 and COUP-TFII, which down-regulate VEGF receptors, VEGFR-2 and NP-1, to control VEGF activity.

Discussion

Endothelial cells are known to display unique cellular features, namely, heterogeneity and plasticity. Recent studies using gain- or loss-of-function mutations and ectopic expression models have revealed that endothelial cells retain astonishing flexibilities in their arteriovenous-lymphatic cell fate specifications. For example, ectopic Notch expression induces the arterial phenotypes in the venous compartment and, reciprocally, inhibition of Notch causes venous phenotypes in the arterial vessels.5-7,49 Although deletion of COUP-TFII resulted in an abnormal arterialization of venous endothelial cells,10 ectopic expression of Proxo1 induces lymphatic reprogramming of blood vascular endothelial cells12,13 and genetic ablation of Prox1 reverses lymphatic cell fate to regain blood vascular phenotypes.18

An interesting notion has been forwarded that the arteriovenous endothelial cell fate specification may be a consequence of a tug of war between 2 dynamic, opposing but complementary forces, likened to yin-yang.7 In this view, the arterial force is dominant in the arterial compartment and suppresses the venous force. Similarly, the venous force is dominant in the vein compartment and represses the arterial force. A number of previous studies have yielded experimental data that are largely consistent with this notion. Similarly, data from our current study enable us to extend this notion to the lymphatic compartment. However, in contrast to arterial or venous vessels that selectively express only their own cell fate regulator (Notch in the arteries and COUP-TFII in the veins), the lymphatic vessels are now found to express all 3 cell fate-regulatory genes, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1.18-20 These findings raised an intriguing question how these 3 seemingly opposing regulatory forces can coexist and eventually exhibit only 1 cell type (ie, LEC). We think that our data presented here provide a compelling answer to this question, namely, “cell fate equilibrium.” We showed that Notch signal pathway suppresses the lymphatic master control gene Prox1 and its interacting partner COUP-TFII in LECs. In turn, Prox1 and COUP-TFII control the expression of VEGFR-2 and neuropilin-1, both of which transduce the VEGF signal to activate Notch signal pathway. Thus, these inter-regulatory relationships form an exquisite, dynamic, and negative feedback loop, where the activity (or force) of each regulatory component, representing an endothelial cell fate, is cross-controlled and balanced to reach an equilibrium toward the lymphatic cell fate in LECs. Furthermore, our working model proposes that LEC fate may not be governed by a 2-way turn ON-OFF switch, rather by a dial switch that allows a gradient increase or decrease in the lymphatic cell fate force. Supporting this notion are the previous finding48 that lymphatic vessels are heterogeneous in regards of podoplanin expression and our current finding that Notch expression is heterogeneous and also inversely associated with podoplanin expression in lymphatic vessels.

In addition, our cell fate equilibrium model predicts the constant requirement of the Prox1-derived lymphatic force to sustain the lymphatic equilibrium in LECs under the normal physiologic condition. Importantly, it has been shown that Prox1 is required to maintain LEC fate during embryonic, postnatal, and adult stage and that inhibition of Prox1 in any predevelopmental or postdevelopmental stages resulted in a loss of LEC identity and acquisition of blood vascular endothelial cell phenotypes.18 Accordingly, when pathologic or genetic insults disturb this cell fate equilibrium, endothelial cells may lose their original identity and exhibit new and mixed cell phenotypes, as exemplified by various vascular malformations or endothelial malignancies. For instance, it has been known for many years that Kaposi sarcoma displays both blood and lymphatic endothelial cell markers, and we and others found that Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus up-regulates Prox1 to induce a pathologic lymphatic reprogramming when the virus infects blood vascular endothelial cells.14-17,50 In addition, various angiosarcomas express mixed endothelial phenotypes of blood and lymphatic capillaries,51 and highly proliferative intratumoral lymphatics abnormally express a blood vessel marker CD34.52 Moreover, proliferating infantile hemangioma cells strongly express the LEC marker LYVE-1.53 Notably, all of these malignancies commonly exhibit a crisis or reprogramming in endothelial cell identity and therefore suffer catastrophic consequences, most notably blood-filled lymphatics, which is also a characteristic feature of Prox1-deleted lymphatic vessels in mice.18

Our feedback model provides an important clue to the question of how COUP-TFII suppresses Notch activity to maintain the venous endothelial cell identity. A previous study showed that genetic ablation of COUP-TFII causes an up-regulation of Notch and its downstream genes,10 and the underlying molecular mechanism remains to be defined. We found that knockdown of COUP-TFII results in up-regulation of VEGFR-2, which transduces the VEGF signal, which is known to up-regulate Notch gene expression.5,6,9 Therefore, we propose that COUP-TFII suppresses Notch gene expression by attenuating VEGF signal transduction pathway. Interestingly, we did not find NP-1 up-regulation by knockdown of COUP-TFII in LECs, which is the case in venous endothelial cells of COUP-TFII null mice.10 We speculate that knockdown of COUP-TFII alone in LECs may not be sufficient for up-regulation of NP-1 because Prox1 continues to repress NP-1 expression.

In conclusion, we established a feedback regulatory model among the 3 major endothelial cell fate regulators, Notch, COUP-TFII, and Prox1, in LECs and demonstrate that their regulatory equilibrium may play an important role in the arteriovenous-lymphatic cell fate specification and LEC plasticity. We think that our current study advances the understanding of endothelial cell fate regulation and provides a molecular basis of the plasticity and heterogeneity of LECs. Moreover, our model may help to define unknown histogenetic origin of various endothelial malignancies with valuable therapeutic insights. Finally, it will be of great interest to know whether a comparable cell fate specification mechanism is at play in other cell types, such as neuronal, hepatic, or retinal lineage cells that express Prox1.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (grants CA69184 and CA92644; M.D.); and the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, the March of Dimes Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R21HL082643 and 1R01HD059762; Y.-K.H.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.K., J.Y., S.L., W.T., B.A., S.R., I.C., H.H.O., and J.W.S. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments; G.P.D. and C.J.K. provided materials; M.D. and Y.-K.H. designed, supervised, and analyzed the research; and Y.-K.H. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Young-Kwon Hong, Departments of Surgery, and of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Southern California, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, 1450 Biggy St, NRT6501, Mail Code 9601, Los Angeles, CA 90033, e-mail: young.hong@usc.edu.

References

Author notes

J.K. and J.Y. contributed equally to this study.