The potential for a splenectomy-sparing medical therapy to manage patients with severe chronic idiopathic (immune) thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) prompted Godeau and colleagues to evaluate rituximab for this indication. Their prospective observational study provides evidence that rituximab may indeed be splenectomy-sparing for some patients.

Rituximab is a chimeric CD20-reactive monoclonal antibody with established efficacy in B-cell lymphomas and rheumatoid arthritis, and with increasing application in a variety of autoimmune disorders, including ITP. In a previous systematic review1 that included 313 rituximab-treated chronic ITP patients—of whom half had not (yet) undergone splenectomy—platelet count response was achieved in 62.5%.

The French investigators have now evaluated this treatment option for adult patients with severe chronic ITP for whom splenectomy was being considered, by performing a multicenter prospective observational study of rituximab administered at 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 consecutive weeks. All of the patients had chronic ITP (> 6 months duration), with severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 30 × 109/L). Moreover, all treatments active against ITP had to have been stopped for at least 2 weeks before the first rituximab infusion, except for corticosteroids, which (if being given) had to be stopped within 21 days following the first rituximab infusion. The study enrolled 60 patients from 8 centers in France. All patients had previously received corticosteroids and/or intravenous gammaglobulin, with more than 80% showing transient response to these first-line therapies, and 21 patients (with a median platelet count of 15 × 109/L) were taking corticosteroids because of bleeding at the time of the first rituximab infusion.

Response to rituximab treatment was defined as a platelet count increase to 50 × 109/L or higher, and with at least a doubling from pretreatment baseline. The primary end point was response that persisted at 1-year follow-up, without institution of any other therapy (including corticosteroids, or a repeat course of rituximab). Secondary end points were response at 2 years and the number of patients requiring splenectomy. The authors used an open-label, single-arm study design, and considered the effect of rituximab significant if it surpassed a preset minimum target of 25% response rate at 1 year (Fleming's single-stage design2 ).

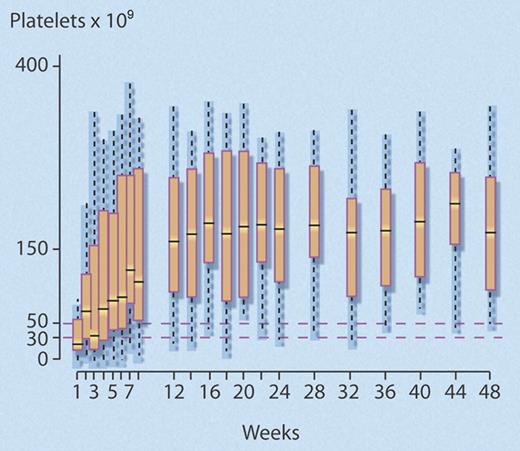

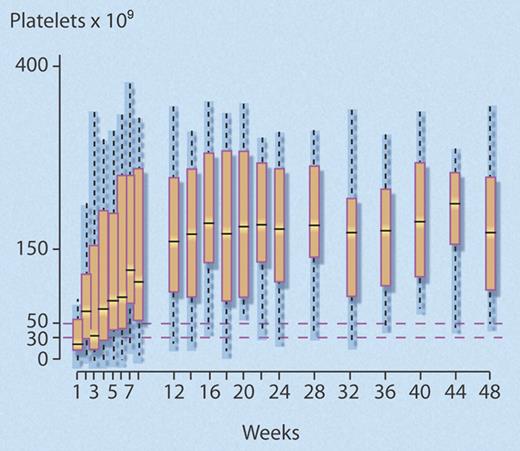

The investigators found that 24 (40%) of 60 (95% confidence interval [CI], 28%-52%) study patients met the predefined criteria for response at 1year, which was significantly better than the 25% comparison rate (P = .007). Median time to response was rapid (4 weeks; interquartile range [IQR], 3-7 weeks), and most (18 of 24) responders maintained normal platelet counts (> 150 × 109/L) after 1 year (see figure). Of the 36 (60%) patients who failed to respond, 25 eventually underwent splenectomy, the efficacy of which did not seem to be altered by prior rituximab treatment, as 15 (60%) of 25 responded.

Successive platelet counts for the 24 (40%) of 60 nonsplenectomized patients with chronic ITP who achieved a good response to rituximab that persisted to 48 weeks. Good response was defined as a platelet count greater than or equal to 50 × 109/L, with at least a doubling of the baseline platelet count, and no requirement for any agent to treat ITP. Median time to response was 4 weeks. Central bar indicates median; top and bottom box limits, 1st and 3rd quartile, respectively; and whisker limits, extreme data points. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

Successive platelet counts for the 24 (40%) of 60 nonsplenectomized patients with chronic ITP who achieved a good response to rituximab that persisted to 48 weeks. Good response was defined as a platelet count greater than or equal to 50 × 109/L, with at least a doubling of the baseline platelet count, and no requirement for any agent to treat ITP. Median time to response was 4 weeks. Central bar indicates median; top and bottom box limits, 1st and 3rd quartile, respectively; and whisker limits, extreme data points. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

Of the 24 responders, 20 maintained their response after 2 years, representing 33.3% of the initial cohort. In a regression analysis, younger age was associated with response to rituximab (odds ratio [OR]: 1.82 [1.26-2.63] per 10 years; P = .001). The data also suggested the magnitude of the initial response to rituximab predicted for response at 1 year, as follows: among 21 patients whose platelet count rose up to or above 150 × 109/L within the first 2 weeks following rituximab infusions, 18 (86%) had good responses at 1 year, while only 6 (40%) of the 15 patients with platelet counts between 50 and 150 × 109/L, and none of the 24 patients whose platelet counts did not rapidly reach 50 × 109/L, achieved a good response at 1 year.

In terms of safety, side effects occurred in 22 (36.7%) of 60 patients. Most were mild infusional reactions, although sigmoiditis and serum sickness were observed. Eight additional severe events that were judged unrelated to rituximab therapy occurred during the 2-year study, including atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and colon and pancreatic cancer.

Based on these results, it appears that the use of rituximab early in the course of chronic ITP may spare or delay splenectomy in some patients. This conclusion is congruent with other lines of evidence suggesting that rituximab may be most effective for patients with a short disease duration,3 possibly as a result of the reversion of T-cell abnormalities following depletion of the CD20+ B-cell pool.4

The observations by Godeau and coworkers will fuel the debate about timing of rituximab in chronic ITP,5 but randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to establish a definitive role for early rituximab administration in nonsplenectomized ITP patients. RCTs are particularly important in ITP because spontaneous remissions are known to occur6 and because formal evaluations of treatment efficacy that include clinically important end points—such as bleeding and quality-of-life—are needed.7

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.E.W. declares no competing financial interests. D.M.A. has received an operating grant from Hoffmann-LaRoche (Mississauga, ON), and has consulted for Amgen (Mississauga, ON). ■