Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by variable clinical outcomes. Outcome prediction at the time of diagnosis is of paramount importance. Previously, we constructed a 6-gene model for outcome prediction of DLBCL patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapies. However, the standard therapy has evolved into rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP). Herein, we evaluated the predictive power of a paraffin-based 6-gene model in R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients. RNA was successfully extracted from 132 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens. Expression of the 6 genes comprising the model was measured and the mortality predictor score was calculated for each patient. The mortality predictor score divided patients into low-risk (below median) and high-risk (above median) subgroups with significantly different overall survival (OS; P = .002) and progression-free survival (PFS; P = .038). The model also predicted OS and PFS when the mortality predictor score was considered as a continuous variable (P = .002 and .010, respectively) and was independent of the IPI for prediction of OS (P = .008). These findings demonstrate that the prognostic value of the 6-gene model remains significant in the era of R-CHOP treatment and that the model can be applied to routine FFPE tissue from initial diagnostic biopsies.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It is characterized by a markedly heterogeneous clinical course and response to therapy that cannot be accurately predicted using standard histopathologic and immunophenotypic evaluation. Presently, the International Prognostic Index (IPI), which classifies patients into clinical risk-groups, is the most commonly used tool to predict response to treatment and survival.1 However, patients with identical IPI scores may still exhibit striking variability in outcome, suggesting the presence of significant residual heterogeneity within each IPI category. The latter is attributed to the molecular heterogeneity that underlies disease aggressiveness and tumor progression and has led to evaluation of molecular markers associated with clinical behavior. Multiple prognostic biomarkers have been identified that are independent of the IPI parameters in assessing patients' risk.2 They have also increased our knowledge of the pathobiology of DLBCL. However, given that lymphoma-associated biologic processes are complex, and involve multiple genes, signaling pathways, and regulatory mechanisms, it is not surprising that single markers are insufficient to accurately capture the heterogeneity of these tumors.

Recent studies have explored the relationships between DLBCL prognosis and multiple molecular features analyzed simultaneously by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of tissue microarrays (TMAs) to assess protein expression or by cDNA microarrays to assess gene expression.3-8 IHC studies are highly appealing for clinical use as they are routinely performed in pathology laboratories. IHC studies of DLBCL markers, however, have yielded conflicting results, probably due to methodological differences (lack of standardization of tissue fixation, antigen retrieval, staining protocols, and cutoffs for designating positivity of expression).2,9 These controversies limit the clinical applicability of IHC biomarkers as prognostic tools. Gene expression profiling studies yielded a “cell of origin” classification offering IPI-independent prognostic value.6,8 However, attempts to construct gene array prognostic models based on a limited number of genes have resulted in nonoverlapping lists of genes in the different models, leaving unanswered questions about their reproducibility and clinical applicability.7,8,10 In addition, whole genome array analysis requires large quantities of RNA extracted from fresh tumor samples, are technically challenging and expensive, and require the availability of fresh or frozen biopsy samples, precluding their widespread use for clinical purposes.

We previously proposed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based model for prediction of outcome in DLBCL patients based on the expression of 6 genes: LMO2, BCL6 and FN1 were associated with longer survival and CCND2, SCYA3, and BCL2 were associated with shorter survival.11 This model classified DLBCL patients into IPI-independent risk groups with significantly different 5-year survivals. This 6-gene model was validated in independent datasets reported by Rosenwald et al8 and Shipp et al7 that were based on different gene expression analysis platforms, Lymphochip or Affymetrix oligonucleotides arrays, respectively. Furthermore, we have confirmed its validity in 2 additional gene expression array datasets published recently12,13 (Table 1). However, all 4 analyzed datasets consisted of DLBCL patients treated with now outmoded chemotherapy. The current gold standard therapy has evolved to include rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP), resulting in significant improvements in patient survival.14-16 This therapeutic evolution might result in a change in the predictive value of biologic markers requiring reevaluation of the biomarkers' prognostic value in patients treated with R-CHOP. Further, the suitability of the 6-gene model for widespread clinical use would be enhanced if this model were adapted for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue and not limited to fresh or frozen specimens. Therefore, in the current study we examined the predictive power of the 6-gene model in FFPE samples of R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients. We demonstrate that the prognostic value of the 6-gene model remains significant in the era of R-CHOP treatment. Using a new RNA extraction methodology, we further show that the 6-gene model can be applied to routine FFPE tissue from initial diagnostic biopsies.

Methods

Patients

A total of 132 specimens from DLBCL patients treated at the British Columbia Cancer Agency (81 patients), University of Miami (27 patients), and Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona (24 patients) were studied. The specimens were selected based on the following criteria: (1) diagnosis of de novo DLBCL clinical stages I to IV; (2) availability of tissue obtained at diagnosis before initiation of therapy; (3) treatment with curative intent with R-CHOP; and (4) availability of follow-up and outcome data at the treating institution. Criteria commonly used for prospective studies such as normal renal and liver functions, absence of comorbid conditions, and good performance status were not applied for case selection. Patients with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma or involvement of central nervous system at presentation were not included in this study. None of the patients in the current study was included in our previous studies of gene expression profiling that led to the derivation of the 6-gene model.11

Institutional review board approval was obtained from all participating institutions for inclusion of anonymized data in this study. The following information at the time of diagnosis was collected: age, sex, performance status, stage, number of extranodal sites involved, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, the presence or absence of systemic (“B”) symptoms, and IPI score. Staging was done in all the patients according to the Ann Arbor system17 based on physical examination, bone marrow biopsy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Patients were categorized into either a low clinical risk group (IPI score 0-2) or a high clinical risk group (IPI score of 3-5), as we also did in our previous study in which the 6-gene model was constructed.11 None of the patients had a known history of HIV infection or other forms of immunosuppression. Follow-up information was obtained from the patients' medical records and included response to initial therapy based on the Cheson criteria,18 overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS). Histologic sections were reviewed to confirm the diagnoses based on features of DLBCL according to the World Health Organization classification of hematopoietic tumors.19

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from two 5-μm-thick slices of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections cut into RNase-free, 2.0-mL Eppendorf tubes, as we have previously reported.20 Briefly, sections were deparaffinized by 2 repeated incubations in 1.5 mL xylene at 37°C for 20 minutes, followed by 2 repeated incubations with 100% ethanol at 37°C for 30 minutes. Ethanol was aspirated and the pellet was allowed to air dry for 5 minutes at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 540 μL RNA lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris/HCL (pH 8.0), 0.1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; pH 8.0), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; pH 7.3) supplemented with 60 μL 60 mg/mL proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and incubated at 60°C for 20 hours until the tissue was completely solubilized. RNA was purified with an equal volume of 70% phenol (pH 4.3):30% chloroform at room temperature and precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol in the presence of 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2 (Hitachi Genetic Systems, Alameda, CA)), and 1 μL of 10 mg/mL of carrier glycogen at −20°C for 1 hour. The RNA pellet was washed once in 75% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 20 to 100 μL RNase-free water. All solutions, including lysis buffer and ethanol/water solutions, were prepared using diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)–treated water. RNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer (Gene Spec I), as we have previously reported.20 The RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol with a minor modification: addition of RNase inhibitor (Applied Biosystems) at a final concentration of 1 U/μL. The complete reaction mixes were incubated at 25°C for 10 minutes and 37°C for 120 minutes.

Real-time reverse transcription (RT)–PCR was performed using the ABI PRISMs 7900HT Sequence Detection System Instrument and software (Applied Biosystems), as previously reported.11,20,21 Briefly, commercially available Assays-on-Demand, consisting of a mix of unlabeled PCR primers and TaqMan minor groove binder (MGB) probe (FAM dye-labeled) were used for measurement of expression of the genes comprising the 6-gene model [BCL6 (Hs00277037_m1), FN1 (Hs00365058_m1), CCND2 (Hs00277041_m1), BCL2 (Hs00153350_m1), LMO2 (Hs00277106_m1), SCYA3 (Hs00234142_m1)]. For an endogenous control, we used Human TaqMan Pre-Developed Assay Reagent (PDAR; Applied Biosystems) for phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), as previously reported.11,21

PCR reactions were prepared in a final volume of 20 μL, with final concentrations of 1× TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and cDNA derived from 20 ng input RNA as determined by spectrophotometric OD260 measurements. Thermal cycling conditions comprised an initial uracil-n-glycosylase (UNG) incubation at 50°C for 2 minutes, AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase activation at 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, and annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 minute. Each measurement was performed in triplicate. Threshold cycle (Ct), the fractional cycle number at which the amount of amplified target reached a fixed threshold-was determined, as previously reported. mRNA level of each test gene was normalized to PGK1 expression and calculated by the ΔCT method. For calibration we used Raji cDNA and/or cDNA prepared from Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), obtaining ΔΔCT values for each gene in each sample.20

Statistical analysis

The normalized gene-expression values were log-transformed (on a base of 2) and the mortality predictor score was calculated based on the following equation: Mortality Predictor Score = (−0.0273 × LMO2) + (−0.2103 ×BCL6) + (−0.1878 × FN1) + (0.0346 × CCND2) + (0.1888 × SCYA3) +(0.5527 × BCL2).11 This score was used as a continuous variable or categorically ranked the patients, allowing their division into 2 groups defined as low- and high-risk groups characterized by mortality prediction score below or above the median. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval between the date of diagnoses to the date of death or last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time interval between the date of initial diagnosis and the date of disease progression or death from any cause, whichever came first, or date of last follow-up evaluation. Survival curves were estimated using the product-limit method of Kaplan-Meier and were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate regression analysis according to the Cox proportional hazards regression model,22 with OS or PFS as the dependent variables, was used to adjust for the effect of the Mortality Predictor Score and IPI or age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI). The t test or Pearson chi-square test were used to compare the clinical characteristics between the low- and high-risk patient groups of the 6-gene model. P less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

To analyze the prognostic value of the 6-gene model in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP, 132 informative patients with a median age of 58 years (range, 16-92) were studied. Patient and disease characteristics, including the 5 clinical parameters that comprise the IPI, are shown in Table 2. The follow-up period ranged from 15 days to 5.6 years (overall median 2.2 years; 25th and 75th quantiles of 1.23 and 3.76 years, respectively), and 38 patients (29%) had died. The median follow-up of patients who are alive was 2.83 years, while the median follow-up for patients who died was 0.84 years. There was no difference in the Kaplan-Meier OS survival curves between patients treated at the British Columbia Cancer Agency and other institutions (University of Miami and Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona; P = .78; Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

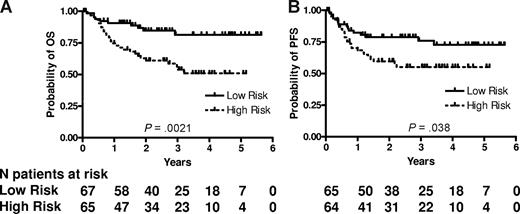

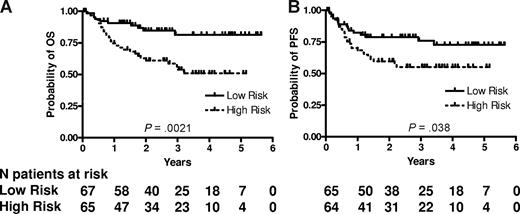

RNA was successfully extracted from all 132 specimens. The median RNA yield per specimen was 9.4 μg (range 2.0-62.3). The expression of LMO2, BCL6, FN1, CCND2, SCYA3, and BCL2 was measured and the mortality predictor score was calculated for each specimen using the equation previously constructed for CHOP-treated patients.11 We ranked the patients according to their mortality predictor scores and divided them based on the median score into 2 groups with low risk (lower than the median, 67 patients) and high risk (higher than the median, 65 patients). The groups were not equal, because 2 patients had an identical mortality score in immediate proximity to the median mortality score. Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the patients according to the risk groups predicted by the 6-gene model. Among the clinical parameters, the 6-gene model–based low- and high-risk groups differed only in their age, with the high-risk group composed of older patients, while distribution of other components of the IPI, composite IPI score, and composite age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI) score was not different between these groups (Table 2). There was a statistically significant difference in OS and PFS between these risk groups (P = .002 and P = .038, respectively; Figure 1). The rates of OS at 2 years in the low and high risk groups were 85% (95% confidence interval [CI] 76%-95%) and 61% (CI 50%-75%), respectively. The median survival has not been reached in either risk group. The model also predicted OS and PFS when the mortality predictor score was considered as a continuous variable (P = .002 and .010, respectively). Examination of the predictive power of individual genes comprising the 6-gene model revealed that expression of LMO2, BCL6, CCND2 and BCL2, examined as continuous variables, was correlated with OS, while expression of LMO2, BCL6 and BCL2 was correlated with PFS (Table 3). Notably, SCYA3 expression tended to be correlated without reaching statistical significance with prolonged survival in the analyzed R-CHOP treated patients, while in CHOP treated patients its expression was correlated with shorter survival.11

6-gene model predicts OS and PFS in patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) in 132 patients with DLBCL show that low-risk patients, as defined by the 6-gene model, exhibit significantly longer OS (P = .002) and PFS (P = .038). For the model based on a continuous variable, P = .002 for OS and P = .010 for PFS. PFS data are missing for 3 patients.

6-gene model predicts OS and PFS in patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) in 132 patients with DLBCL show that low-risk patients, as defined by the 6-gene model, exhibit significantly longer OS (P = .002) and PFS (P = .038). For the model based on a continuous variable, P = .002 for OS and P = .010 for PFS. PFS data are missing for 3 patients.

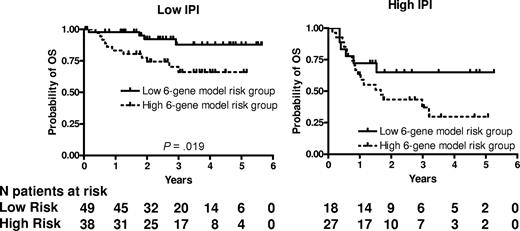

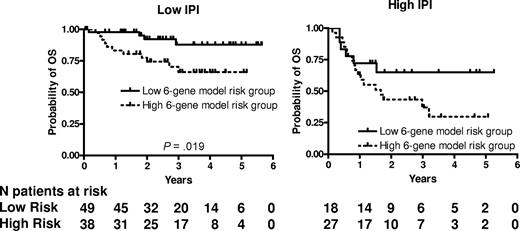

We next examined whether the prognostic significance of the 6-gene model based on the mortality predictor score was independent of the IPI score. A multivariate Cox regression analysis that included IPI scores and mortality predictor scores with OS or PFS as the dependent variables was performed. Both the IPI and the mortality predictor score (either as a categorical or continuous variable) were independent predictors of OS (Table 4) but in PFS analysis, only the IPI remained statistically significant. Notably, both the mortality prediction score and the IPI had approximately equal contribution to the prediction of the OS in the multivariate analysis. Because age was the only clinical parameter that was significantly different between the 6-gene model–based low- and high-risk groups, we performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis that included aaIPI scores and mortality predictor scores with OS or PFS as the dependent variables. Both the aaIPI and the mortality predictor score (either as a categorical or continuous variable) were independent predictors of both OS, but again in the PFS analysis, only the IPI remained statistically significant (Table 4). We next examined the prognostic power of the 6-gene model in patients with low (n = 87) and high (n = 45) IPI scores (Figure 2). In the subgroup with low IPI scores, patients with low mortality predictor scores exhibited significantly longer OS (P = .019). The group with low IPI and low mortality predictor scores exhibited a survival plateau at 87% starting from 3 years from diagnosis, which suggests that almost all patients in this group were cured. No difference in OS was observed between patients with low and high mortality predictor scores in the subgroup with high IPI scores, probably because of a small number of patients with a high IPI score, although a trend for a survival plateau was observed in the high IPI–low mortality predictor score group.

6-gene model is independent of the IPI. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS in low clinical risk (IPI score, 0-2) and high clinical risk (IPI score, 3-5) grouped into low- and high-risk groups based on the mortality prediction score calculated from the 6-gene model.

6-gene model is independent of the IPI. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS in low clinical risk (IPI score, 0-2) and high clinical risk (IPI score, 3-5) grouped into low- and high-risk groups based on the mortality prediction score calculated from the 6-gene model.

Discussion

The marked variability in the survival of DLBCL patients presents a continuous challenge to physicians and necessitates the search for better treatments and the ability to predict outcome either before or shortly after treatment initiation. Predicting outcome is important to facilitate discussion between physicians and patients, improve participation of patients in treatment decisions and allow patients to make realistic plans for their future. Furthermore, the ability to predict outcome is also important for the design of and stratification of patients enrolled on clinical trials, for comparison between and uniform reporting of studies, for development of guidelines for initial treatment, and for evaluation of new therapeutic targets. Moreover, understanding the mechanisms that underlie the predictive power of biomarkers may form the basis for future therapeutic interventions.

The 6-gene model that we had previously constructed for prediction of outcome in DLBCL patients fulfilled many features desired of prognostic biomarkers: it was confirmed in independent groups of patients (Table 1), it relied on robust and reproducible real-time PCR methodology and its predictive value was independent of other known prognostic factors, such as the IPI. However, the model did not meet one very important criterion: it was not easily available for widespread clinical use because it required RNA extracted from fresh or frozen specimens. Furthermore, changes in the therapeutic approach and introduction of new therapies require reassessment of the clinical applicability of previously recognized prognostic factors. Indeed, initial studies suggest that some individual biomarkers (BCL2 and BCL6) may lose their predictive power after addition of rituximab to the treatment regimen.23-25 Although validation of these initial observations in independent cohorts of R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients is needed, these findings dictate the need to reassess the 6-gene model in patients treated with R-CHOP.

To address these considerations, we set out to optimize methodology for RNA extraction from FFPE lymphoid tissue.20 The process of formalin fixation is known to contribute to RNA degradation or modification, which results in poor extractability of high-quality RNA by routine RNA extraction methods.26 Application of previously reported methodologies used for FFPE breast tissue did not yield reproducible results in our hands.20 Therefore, we recently developed and optimized a method for RNA extraction from FFPE lymphoid tissue.20 This method is based on modification of the lysis buffer, optimization of the digestion temperature and application of large quantities of proteinase K for complete recovery of the genetic material. It allows extraction of a sufficient quantity of high-quality long fragments of RNA amenable for quantification by either real-time PCR or possibly gene expression profiling. Furthermore, the use of this RNA for real-time PCR analysis of genes implicated in the prognosis of DLBCL demonstrated that there is an extremely high correlation (R > 0.90) in normalized gene expression between paired frozen and FFPE samples.20 Moreover, this method allows extraction of RNA from archived specimens (some of which had been stored for up to 20 years). Slight variations in formalin fixation that may exist between different institutions did not affect extractability or RNA yield (unpublished observations based on extraction of RNA from 7 different institutions).

Using this methodology we were successful in extracting high quality RNA in all 132 patient samples used in the current study. Testing the paraffin-based 6-gene model in R-CHOP–treated patients demonstrated that this model retained its predictive power for OS and PFS and was independent of the IPI score for prediction of OS. Because the number of events observed in R-CHOP–treated patients is smaller than previously seen in CHOP-treated patients,14 examination of the model in a larger cohort of patients is needed to confirm the loss of the IPI independence of the model for prediction of PFS in multivariate analysis. Of note, the patients in the low-risk group defined by the 6-gene model were younger than the patients in the high-risk group, which suggests that there may be differences in the biologic characteristics of the DLBCL tumors in different age groups.

Analysis of individual genes contained within the 6-gene model and patient outcome demonstrated that the expression of some of the genes singly was correlated with outcome in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. Higher expression of LMO2 mRNA was correlated with prolonged OS and PFS, thus confirming our recent IHC findings of longer survival in R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients whose tumors express high levels of LMO2 protein.3 Of note, there was no overlap in the FFPE samples used for these 2 studies. Similarly, higher expression of BCL6 mRNA was also correlated with longer OS and PFS of R-CHOP–treated DLBCL in our study, in contrast to the recent report by Winter et al25 that analyzed expression of BCL6 protein, suggesting either that this latter study might be underpowered and would benefit from reanalysis in a larger cohort of patients or that there are differences in predictive potential of BCL6 mRNA and protein expression. Expression of the BCL2 mRNA was correlated with shorter OS and PFS in our study. A recent IHC-based analysis of BCL2 protein expression in R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients showed no correlation with clinical outcome,23 although mRNA status was not reported in the latter study. Interestingly, expression of SCYA3 mRNA tended to be correlated with improved outcome in R-CHOP–treated patients, while it was correlated with poor outcome in our previous study of CHOP-treated DLBCL patients.11 This gene probably reflects tumor microenvironment, similar to FN1. SCYA3 is a CC chemokine that recruits a variety of cells to sites of inflammation27 and may reflect the role of tumor microenvironment in DLBCL pathogenesis. However, presently its function in B-cell lymphomas is unknown. It is possible that addition of rituximab alters SCYA3 downstream biologic function and affects its role in outcome prediction. Expression of genes reflecting microenvironment inflammatory response was previously reported to be correlated with response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma.28 Further studies to confirm these observations are needed.

We have shown that the paraffin-based 6-gene model is a robust predictor of clinical outcome in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. However, several additional hurdles need to be addressed before it can be applied in routine clinical practice. The paraffin-based 6-gene model needs to be tested by the performance of real-time PCR measurements at other institutions in independent cohorts of R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients. Furthermore, this model needs to be validated in a prospective multiinstitutional study of R-CHOP–treated DLBCL patients with a standardized written protocol that incorporates strict eligibility criteria, a uniform treatment plan, uniform sample collection and handling, and well-defined primary endpoints. Such a study is in progress. IHC analysis of the predictive power of the 6 proteins, comprising the model and comparison of the IHC-based and paraffin-based RT-PCR 6-gene models, may help to determine the best platform for future clinical application; however, presently, monoclonal antibodies useful for IHC are not available for all 6 proteins. If it can overcome these obstacles, the 6-gene model may be ready for incorporation into routine clinical practice for predicting prognosis in patients with DLBCL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants CA109335, CA122105, CA34233, and CA33399; a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Support of Continuous Research Excellence (SCORE) grant, National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) Terry Fox Program Project Grant 016003, and the Dwoskin Family Foundation. The work of R.M. was supported by a fellowship from Fundación Caja Madrid (Spain).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: R.M., J.C., and I.S.L. performed experiments and analyzed the data; R.T. analyzed the data, N.A.J., L.H.S., J.B., R.A., J.M.C., and R.D.G. contributed valuable tissues and clinical information; Y.N., G.E.B., and R.D.G. performed pathologic analysis of the specimens; and R.L. and I.S.L. conceptualized the idea of the study. All authors contributed to writing and approved the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Izidore S Lossos, MD, Sylvester Compre-hensive Cancer Center, Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology-Oncology, University of Miami, 1475NW 12th Ave (D8-4), Miami, FL 33136; e-mail: Ilossos@med.miami.edu.

References

Author notes

*R.D.G. and I.S.L. contributed equally to this work.