Abstract

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates the proliferation of bone marrow granulocytic progenitor cells and promotes their differentiation into granulocytes. G-CSF is therefore an important component of immune defense against pathogenic microorganisms: recombinant human G-CSF (rhG-CSF) is used to treat patients with a variety of neutropenias. In the present study, we screened approximately 10 000 small nonpeptidyl compounds and found 3 small compounds that mimic G-CSF in several in vitro and in vivo assays. These compounds induced G-CSF–dependent proliferation, but had no effect on interleukin-3–dependent, interleukin-2–dependent, interleukin-10–dependent, thrombopoietin (TPO)–dependent, or erythropoietin (EPO)–dependent proliferation. Each compound induced the phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription–3 (STAT3) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in a G-CSF–dependent cell line and in human neutrophils. In addition, these compounds induced hematopoietic colony formation from primary rat bone marrow cells in vitro. When subcutaneously injected into normal rats, they caused an increase in peripheral blood neutrophil counts. Furthermore, when they were administered to cyclophosphamide-induced neutropenic rats, blood neutrophil levels increased and remained elevated up to day 8. We therefore suggest that these small nonpeptidyl compounds mimic the activity of G-CSF and may be useful in the treatment of neutropenic patients.

Introduction

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates proliferation of bone marrow progenitor cells and promotes their differentiation into granulocytes.1 It exerts its biologic effects by binding to its cognate cell surface receptor, a member of the cytokine receptor superfamily.2,3 Stimulation of granulocytic cells with G-CSF leads to the activation of the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.3-7 Following binding, JAK1 and JAK2 tyrosine kinases are phosphorylated. The activated JAKs induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5, which then dimerize, translocate to the nucleus, and bind to palindromic sequence elements in the DNA. These DNA elements are related to the interferon-γ activation sites (GASs) of interferon-responsive genes, and the binding of STAT3 and STAT5 activates transcription.8

STAT3 activation is essential for G-CSF–dependent cell proliferation and granulocyte differentiation.9 Activation of the JAKs requires the membrane-proximal cytoplasmic regions of the G-CSF receptor (box 1 and box 2).6,10 However, both membrane-proximal and membrane-distal regions of the G-CSF receptor are required for MAPK-dependent activation and proliferation.4,5

Recently, transgenic mice lacking G-CSF were generated by targeted disruption of the G-CSF gene in embryonic stem cells.11 The G-CSF–deficient mice had chronic neutropenia and impaired neutrophil mobilization, resulting in a marked inability to control infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Thus, G-CSF is an important factor in immune defense against pathogenic microorganisms. Recombinant human G-CSF is in fact used to treat patients suffering from a variety of neutropenias.12 These patients have well-defined metabolic defects, the control of which depends on exogenous injections of peptidyl G-CSF. It could be useful to develop alternative therapies for these disorders involving small compounds that mimic human G-CSF. A small nonpeptidyl molecule, SB247464, was found to activate mouse G-CSF receptors,13 but was unable to stimulate human G-CSF receptors. Here, we describe 3 small nonpeptidyl compounds that mimic human and rat G-CSF in vitro and in vivo, and reduce neutropenia.

Materials and methods

Hematopoietic growth factor and reagents

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 were synthesized by SSP (Chiba, Japan). Recombinant mouse interleukin-3 (rmIL-3), recombinant human G-CSF (rhG-CSF), recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO), recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO), recombinant human interleukin-10 (rhIL-10), and recombinant mouse interleukin-2 (rmIL-2) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Plasmids

Human G-CSF receptor (GCSFR), EPO receptor (EPOR), TPO receptor (TPOR), and IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) cDNAs were amplified from Quick-clone (human spleen) (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primer pairs used were as follows: GCSFR forward, 5′-AAGAATTCATGGCAAGGCTGGGAAACTGCA-3′; GCSFR reverse, 5′-GAATTCTTCTAGAAGCTCCCCAGCGCCTCCA-3′; EPOR forward, 5′-AAGAATTCATGGACGACCTCGGGGCGTCCCTCT-3′; EPOR reverse, 5′-AAGAATTCCTAAGAGCAAGCCACATAGCTGGGG-3′; TPOR forward, 5′-AAGAATTCATGCCCTCCTGGGCCCTCTTCATGG-3′; TPOR reverse, 5′-AAGAATTCTCAAGGCTGCTGCCAATAGCTTAGT-3′; IL-10R forward, 5′-AAGAATTCATGCTGCCGTGCCTCGTAGTGCTGC-3′; and IL-10R reverse, 5′-AAGAATTCGTCACTCACTTGACTGCAGGCTAGA -3′. Amplification was performed with a Perkin Elmer DNA thermal cycler 9600 (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA); it involved 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 seconds, and annealing and extension at 68°C for 4 minutes. The PCR products were cloned into vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the nucleotide sequences of the inserts were determined. The full-length cDNAs were ligated into the EcoRI site of vector pIRESpuro (Clontech) to create pIRESpuro-GCSFR, pIRESpuro-IL-10R, pIRESpuro-TPOR, and pIRESpuro-EPOR.

Stable transfection with GCSFR, EPOR, TPOR, or IL-10R expression plasmids

The mouse pro-B cell line BAF/B03 was maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and rmIL-3 (7 × 10–10 M). They were transfected by electroporation with p–internal ribosome entry site–puromycin GCSFR (pIRESpuro-GCSFR) (2 μg), pIRESpuro-EPOR (4 μg), pIRESpuro-TPOR (4 μg), or pIRESpuro-IL-10R (3 μg). Clones resistant to puromycin (2 μg/mL) (Sigma) were selected by limiting dilution in medium containing rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M), rhEPO (1 U/mL), rhTPO (6 × 10–10 M), or rhIL-10 (5 × 10–10 M). The stably transfected cell lines obtained are referred to as BAF/GCSFR, BAF/EPOR, BAF/TPOR, and BAF/IL10R, respectively.

Cell growth

BAF/B03 was maintained in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS and rmIL-3 (7 × 10–10 M). The BAF/GCSFR, BAF/EPOR, BAF/TPOR, and BAF/IL10R cell lines and the IL-2–dependent cell line CTLL-2 were maintained in DMEM (Sigma) with 10% FBS and rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M), rhEPO (1 U/mL), rhTPO (6 × 10–10 M), rhIL-10 (5 × 10–10 M), or rmIL-2 (6 × 10–10 M), respectively. Neutrophils were purified from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (after informed consent) by centrifugation on Mono-poly resolving medium (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan). Fresh peripheral blood was layered onto Mono-poly resolving medium and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 400g at room temperature; the neutrophil fraction was washed with PBS and recentrifuged for 10 minutes at 250g. The neutrophil purity was demonstrated by Wright-Giemsa staining (greater than 98% purity). The purified neutrophils were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS, made freshly for each experiment. They were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air in a humidified atmosphere.

Proliferation assay

Cells were cultured at 5 × 104 cells per well for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhG-CSF, rmIL-3, rhEPO, rhTPO, rhIL-10, rmIL-2, or small compounds, in the presence of 0.001% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Cell proliferation was measured with a cell counting kit (Dojin, Kumamoto, Japan) with 2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (WST-1) (5 × 10–3 M) and 1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methylsulfate (1-methoxy PMS) (2 × 10–4 M) as substrate, and cultured for 2 hours at 37°Cin a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Optical density was measured at 450 nm in a microplate reader (Corona; Ibaragi, Japan).

Immunoblot analysis

BAF/GCSFR cells were deprived of serum and growth factors for 6 hours at 37°C, and 3 × 107 cells per sample were incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes with a small compound (10–6 M) or rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). The reaction was terminated with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were lysed by incubation for 1 hour at 4°C in lysis buffer, M-PER (Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 2 mM Na3VO4 and with 5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 30 μg/mL leupeptin, and 10 μg/mL aprotinin as protease inhibitors. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 15 000g for 20 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant stored at –80°C until use. Protein concentration was determined with the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins in the cell lysates (50 μg) were suspended in Laemmli reducing sample buffer, consisting of 58 mM Tris-HCl (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl), 6% glycerol, 1.67% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.002% bromophenol blue, and 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (pH 6.8), and boiled for 5 minutes, then separated by gel electrophoresis (5% to 20% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [SDS-PAGE]). Following transfer of the proteins to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, blocking was performed with Tris-buffered saline–Tween (TBST) (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) containing 5% bovine saline albumin (BSA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After blocking, the membrane was probed with antibodies for 1 hour in blocking buffer. The antibodies used were against STAT3 (1:1000 dilution) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); phospho-STAT3 (1:500 dilution) (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); MAPK (1:1000 dilution) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA); or phospho-MAPK (1:1000 dilution) (New England Biolabs). After washing in TBST, the membrane was incubated with the second antibody (goat-antirabbit immunoglobulin G [IgG] coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA), and developed by means of the electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Purified human neutrophils (1.9 × 107 cells per condition) were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes with the small compounds (10–6 M) in the presence of 0.001% DMSO, or with rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). Cell lysates were prepared as described. For STAT3 immunoprecipitation, proteins in the cell lysates (500 μg) were incubated overnight at 4°C with an antibody against STAT3 (4 μg) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and protein A–sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were added for 1 hour at 4°C. After 3 washes in lysis buffer, proteins were eluted from the beads by boiling in Laemmli reducing sample buffer. They were then separated by gel electrophoresis (5% to 20% SDS-PAGE), transferred to a PVDF membrane, and detected by means of an antibody against phospho-STAT3. Another specific antibody was used to detect STAT3 expression. Immunoblotting of activated MAPK was performed with antibodies directed against phospho-MAPK.

Colony-forming assay

Bone marrow cells were harvested from both femoral bones of 8-week-old male Sprague-Dawley CD rats (Charles River Japan, Yokohama, Japan). Cells (5 × 104/0.5 mL) were incubated at 37°C for 8 days with varying concentrations of the small compounds, or of rhG-CSF, in DMEM containing 30% FBS, 0.9% methylcellulose, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1% BSA in a humidified CO2 incubator. Colonies containing more than 30 cells were counted by phase-contrast microscopy. The number of granulocyte colony-forming unit (CFU-G) colonies per 5 × 104 cells is shown.

Cytologic analysis

Colonies from the colony-forming unit assay were recovered from the methylcellulose layer, and the cells in these colonies were washed with PBS, fixed by Side Spin (IRIS, Norwood, MA), and stained with Diff Quik (Kokusai Shiyaku, Hyogo, Japan).

Compounds

Cyclophosphamide (CPA) (Endoxan; Shionogi Pharmaceuticals, Osaka, Japan) was dissolved in sterile distilled water. Commercial filgrastim (rhG-CSF; Kirin Brewery, Tokyo, Japan) and SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 nitrate were dissolved in vehicle solution (saline containing 1% DMSO).

Animals and treatments

Male Sprague-Dawley–derived CD rats (CD rats) aged 6 weeks were obtained from Charles River Japan. Following a 7-day acclimatization period, they were randomly assigned to different groups and housed, 5 per cage, in a room at 21 to 26°C with 50% to 60% humidity, on a 12:12–hour light-dark schedule. In the single-administration study on normal rats, 11 groups of 5 male CD rats were used. They each received a single subcutaneous dose of 0 (vehicle control, saline containing 1% DMSO); 0.3, 3, or 30 mg/kg SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 nitrate; or 100 μg/kg rhG-CSF. In the repeated-administration study on normal rats, 11 groups of 5 male CD rats were used. They received 4 single daily subcutaneous treatments (days 1-4) of 0 (vehicle control, saline containing 1% DMSO); 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 nitrate; or 30 μg/kg rhG-CSF. In the study on neutropenic rats, again, 11 groups of 5 male CD rats were used. All received a single intraperitoneal dose of 25 mg/kg CPA (day 0). They also received daily subcutaneous doses of 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 nitrate or 30 μg/kg rhG-CSF on days 1-4, and the remaining CPA group received vehicle (saline containing 1% DMSO).

Parameters evaluated

All the animals were checked daily for general conditions and potential clinical symptoms. To determine hematologic parameters, blood samples (0.2 mL per animal) were collected from the orbital venous plexus with the use of slight diethylether anesthesia. Samples from the single administration were taken at 0, 5, 10, 24, and 48 hours after administration. Blood samples from multiple administration of normal and neutropenic groups were taken during the pretest period (day –2) and on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. On days 1, 2, 3, and 4, they were taken 8 hours after each administration. Red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and platelets were counted by means of an automatic microcell counter F-820 (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Differential cell counts were performed on at least 100 cells per blood smear stained with Diff Quik. To calculate the absolute numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes in peripheral blood, the total leukocyte count was multiplied by the corresponding differential count. The body weight of each of the animals was recorded on day –2 and day 9.

Statistical analysis

Significance was determined by Student t test or Dunnett test. Data were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistically significant differences were P < .05 and P < .01.

Results

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 stimulate proliferation of BAF/GCSFR cells

We have developed a high-throughput, cell proliferation–based screening assay using the human G-CSF–dependent cell line BAF/GCSFR to identify small compounds that mimic human G-CSF. This cell line was originally derived from the mIL-3–dependent cell line BAF/B03.14 The BAF/GCSFR cells proliferate in response to rhG-CSF or rmIL-3 and undergo apoptosis when deprived of these growth factors. In the assay, the BAF/GCSFR cells are exposed to synthetic compounds at a concentration of 10–6 M, and cell proliferation is determined after 48 hours. Among the approximately 10 000 small synthetic compounds screened, we identified 3 related active compounds, designated SSCL02446, SSCL02447, and SSCL02448, in the primary screening. These 3 compounds and a related inactive compound, SSCL02444, are depicted in Figure 1A. All are imidazole derivatives; SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 have long alkoxy chains, while SSCL02444 has a fluorobenzyloxy structure at the same position.

Structure and in vitro effects of the 3 active compounds and the related inactive compound. (A) The active compounds along with the related inactive compound are as follows: SSCL02446, 2-[5-chloro-2-(heptyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02447, 2-[5-chloro-2-(octyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02448, 2-[5-chloro-2-(nonyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; and SSCL02444: 2-[2-(2-fluorobenzyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-pentanol. (B) G-CSF–induced cell proliferation. The BAF/GCSFR cells were cultured for 48 hours with varying concentrations of rhG-CSF, SSCL02446, SSCL02447, SSCL02448, or SSCL02444. Cell proliferation was measured with WST-1/1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methyl sulfate (PMS) as substrate (n = 5; mean). Standard errors of the mean were less than 5% and were therefore omitted. (C) IL-3–dependent cell proliferation. BAF/B03 cells were cultured for 48 hours in media containing various concentrations of rmIL-3, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (D) EPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/EPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhEPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (E) TPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/TPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhTPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (F) IL-10–dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/IL10R cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhIL-10, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (G) IL-2–dependent cell proliferation. CTLL-2 cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium containing various concentrations of rmIL-2 or the small compounds.

Structure and in vitro effects of the 3 active compounds and the related inactive compound. (A) The active compounds along with the related inactive compound are as follows: SSCL02446, 2-[5-chloro-2-(heptyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02447, 2-[5-chloro-2-(octyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02448, 2-[5-chloro-2-(nonyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; and SSCL02444: 2-[2-(2-fluorobenzyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-pentanol. (B) G-CSF–induced cell proliferation. The BAF/GCSFR cells were cultured for 48 hours with varying concentrations of rhG-CSF, SSCL02446, SSCL02447, SSCL02448, or SSCL02444. Cell proliferation was measured with WST-1/1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methyl sulfate (PMS) as substrate (n = 5; mean). Standard errors of the mean were less than 5% and were therefore omitted. (C) IL-3–dependent cell proliferation. BAF/B03 cells were cultured for 48 hours in media containing various concentrations of rmIL-3, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (D) EPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/EPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhEPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (E) TPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/TPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhTPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (F) IL-10–dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/IL10R cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhIL-10, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (G) IL-2–dependent cell proliferation. CTLL-2 cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium containing various concentrations of rmIL-2 or the small compounds.

Stimulation by SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 was dose dependent and maximal at 10–6 M, as with rhG-CSF (Figure 1B). SSCL02444 did not induce growth at any dose (Figure 1B), suggesting that the alkoxy chain is the key structural feature responsible for activity. To determine whether the activity of these compounds is specific to G-CSF–dependent cell proliferation, we tested them on cells that proliferate in response to rmIL-3, rhEPO, rhTPO, rhIL-10, or rmIL-2. They had no effect (Figure 1C-G). Thus, all 3 compounds appear to be specific agonists of the G-CSF receptor.

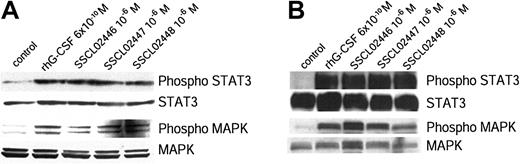

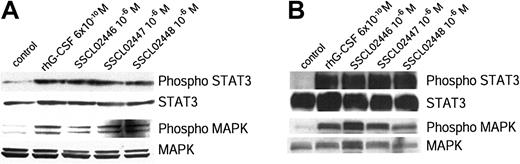

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 stimulate phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAP kinase

G-CSF has been shown to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5, as well as of its own receptor.6,10,15-18 Activation of STAT3 in this way is required for G-CSF–dependent proliferation and granulocyte differentiation.19 To determine whether the 3 alkoxy chain compounds activate this signal transduction pathway in the same way as G-CSF, BAF/GCSFR cells were treated with these compounds or rhG-CSF. Proteins in the cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, and phospho-STAT3 and STAT3 were detected by immunoblotting. All 3 compounds induced phosphorylation of STAT3 (Figure 2A), as did G-CSF.6,9,10,15-18 As expected, the inactive SSCL02444 did not cause any phosphorylation (data not shown). Because G-CSF has been shown to activate the Ras/MAPK pathway,4,6,20 we next examined activation of MAPK by the small compounds. These also phosphorylated MAPK (Figure 2A).

Tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in BAF/GCSFR cells and human neutrophils. (A) BAF/GCSFR cells were treated for 15 minutes at 37°C with the small compounds (10–6 M) or rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and examined with antibodies against STAT3, phospho-STAT3, MAPK, or phospho-MAPK. (B) Phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in human neutrophils. Purified human neutrophils were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with small compounds (10–6 M) or rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). Proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with an antibody against STAT3. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with an antibody against phospho-STAT3. Expression of STAT3 was detected with an antibody specific to this protein. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and the gels stained with antibodies to phospho-MAPK and MAPK. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in BAF/GCSFR cells and human neutrophils. (A) BAF/GCSFR cells were treated for 15 minutes at 37°C with the small compounds (10–6 M) or rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and examined with antibodies against STAT3, phospho-STAT3, MAPK, or phospho-MAPK. (B) Phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in human neutrophils. Purified human neutrophils were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with small compounds (10–6 M) or rhG-CSF (6 × 10–10 M). Proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with an antibody against STAT3. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with an antibody against phospho-STAT3. Expression of STAT3 was detected with an antibody specific to this protein. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and the gels stained with antibodies to phospho-MAPK and MAPK. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments.

To determine whether their activity is species-specific, we examined phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in healthy human neutrophils. Lysates of treated human neutrophils were immunoprecipitated with anti-STAT3 and immunoblotted. Again, all 3 compounds phosphorylated STAT3 and MAPK (Figure 2B).

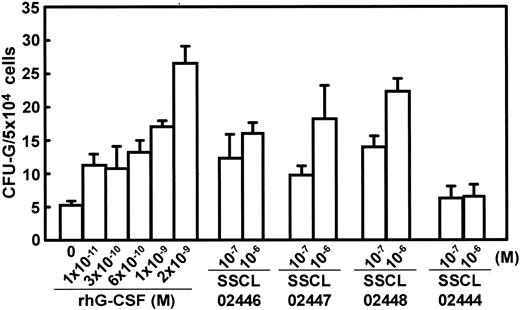

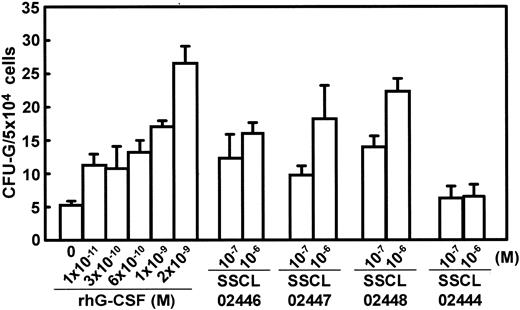

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 stimulate granulocyte colony formation in vitro

G-CSF normally acts on granulocytic precursor cells in the bone marrow, inducing their proliferation and differentiation.2,21 To determine whether SSCL02446, SSCL02447, and SSCL02448 also act on rodent G-CSF receptors, normal CD rat bone marrow cells were cultured for 8 days in the presence of each compound. The numbers of granulocytic colonies CFU-Gs1 were counted by microscopy. All the compounds stimulated the formation of granulocyte colonies (Figure 3), and the optimal concentrations were again 10–6 M in each case. However, the colonies formed in response to the 3 novel compounds appeared uniformly smaller than those induced by rhG-CSF (data not shown). Colonies stimulated by G-CSF were mainly CFU-G colonies (approximately 70%), and the remaining colonies were granulocytes and macrophages (CFU-GMs) or only macrophages (CFU-Ms) (Table 1). Colonies stimulated by SSCL02446, SSCL02447, and SSCL02448 were mainly CFU-G colonies (approximately 60%), and the remaining colonies were CFU-GMs or CFU-Ms (Table 1). Thus, each of the novel compounds mimics rat and human G-CSF.

Effect of SSCL02446 to SSCL0248 and G-CSF on granulocyte colony formation by rat bone marrow cells. Bone marrow cells were plated in methylcellulose-containing medium supplemented with various concentrations of the small compounds or rhG-CSF, and incubated at 37°C for 8 days. Colonies were observed microscopically, and those containing more than 30 cells were counted (n = 5; mean ± SEM). Thereafter, colonies were recovered from the methylcellulose layer and analyzed by Diff Quik stain.

Effect of SSCL02446 to SSCL0248 and G-CSF on granulocyte colony formation by rat bone marrow cells. Bone marrow cells were plated in methylcellulose-containing medium supplemented with various concentrations of the small compounds or rhG-CSF, and incubated at 37°C for 8 days. Colonies were observed microscopically, and those containing more than 30 cells were counted (n = 5; mean ± SEM). Thereafter, colonies were recovered from the methylcellulose layer and analyzed by Diff Quik stain.

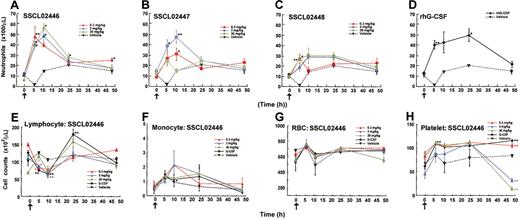

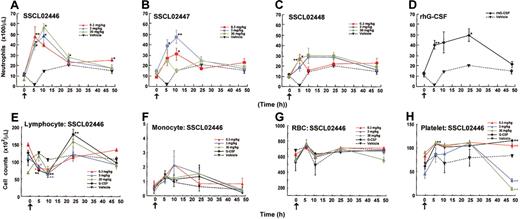

A single administration of SSCL02446 to SSCL0248 causes neutrophil release from bone marrow

Having established that SSCL02446, SSCL02447, and SSCL02448 stimulate rat granulopoietic precursor cells in vitro, we found it of interest to determine whether they also induce granulopoiesis in vivo. Since administration of human G-CSF to normal rats has been shown to increase peripheral neutrophils,22-24 we used this criterion to test for granulopoiesis in vivo. As shown in Figure 4A-C, subcutaneous administration of any of the compounds to normal CD rats resulted in an increase in peripheral blood neutrophils. Neutrophil counts increased 2- to 3-fold compared with vehicle-injected rats for 10 hours, and then declined. SSCL02446 was the most potent of the 3 compounds (Figure 4A). As expected, rhG-CSF also increased the number of circulating neutrophils (Figure 4D). A single administration of SSCL02446 had no significant effect on the number of monocytes and RBCs (Figure 4F-G). Lymphocyte counts were less affected by SSCL02446 (Figure 4E). Platelet counts decreased slightly and transiently at 48 hours (Figure 4H). A single administration of rhG-CSF increased numbers of lymphocytes, and the effect on RBC, monocyte, and platelet counts was less marked. Administration of vehicle had no effect on cell counts.

Effect of a single administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in normal CD rats. Male CD rats were injected subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (panel A), SSCL02447 nitrate (panel B), SSCL02448 nitrate (panel C), or rhG-CSF (panel D). Neutrophil (panels A-D), lymphocyte (panel E), monocyte (panel F), RBC (panel G), and platelet (panel H) counts were measured in peripheral blood. The arrows indicate the times of administration of small compounds and rhG-CSF. Blood samples were collected from the orbital sinus at 0, 5, 10, 24, and 48 hours after administration. Each point represents the mean of cell counts on 4 or 5 rats ± SEM. Differential cell counts were performed on at least 100 cells in each blood smear stained with Diff Quik. Significant differences (*P < .05; **P < .01) from vehicle were assessed by the Dunnett test.

Effect of a single administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in normal CD rats. Male CD rats were injected subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (panel A), SSCL02447 nitrate (panel B), SSCL02448 nitrate (panel C), or rhG-CSF (panel D). Neutrophil (panels A-D), lymphocyte (panel E), monocyte (panel F), RBC (panel G), and platelet (panel H) counts were measured in peripheral blood. The arrows indicate the times of administration of small compounds and rhG-CSF. Blood samples were collected from the orbital sinus at 0, 5, 10, 24, and 48 hours after administration. Each point represents the mean of cell counts on 4 or 5 rats ± SEM. Differential cell counts were performed on at least 100 cells in each blood smear stained with Diff Quik. Significant differences (*P < .05; **P < .01) from vehicle were assessed by the Dunnett test.

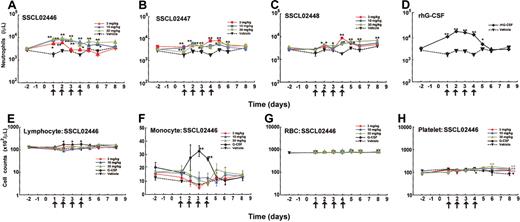

Repeated administration of SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 causes neutrophil release from bone marrow

To further characterize neutrophil release from bone marrow, SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 were administered subcutaneously to normal rats once daily for 4 days, and cell numbers and cell types were characterized. In the single-administration study, SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 increased neutrophil count within 10 hours; therefore, on days 1 to 4, blood samples were collected 8 hours after each administration. As shown in Figure 5A-C, a significant increase in peripheral neutrophil count was observed with each compound. SSCL02446 was the most potent of the 3 compounds, causing a 3- to 4-fold rise in neutrophil count on day 2 (Figure 5A). These levels were maintained until day 4 and returned to normal after cessation of administration. As expected, rhG-CSF also increased the number of circulating neutrophils (Figure 5D). Repeated administrations of SSCL02446 produced no significant change in numbers of lymphocytes, monocytes, or RBCs (Figure 5E-G). Platelet counts were slightly increased on day 6 and day 8 (Figure 5H). Repeated administration of rhG-CSF raised the number of lymphocytes and monocytes transiently, as reported previously25 (Figure 5E-F). RBC and platelet counts were less affected than neutrophil counts (Figure 5G-H).

Effect of repeated administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in normal CD rats. Male CD rats were injected subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (A), SSCL02447 nitrate (B), SSCL02448 nitrate (C), or rhG-CSF (D). Neutrophil (A-D), lymphocyte (panel E), monocyte (panel F), RBC (panel G), and platelet (panel H) counts were measured in peripheral blood. Peripheral blood cells were collected on day –2 and days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. On days 1, 2, 3 and 4, they were collected 8 hours after each administration. Other details were as described in the legend to Figure 4.

Effect of repeated administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in normal CD rats. Male CD rats were injected subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (A), SSCL02447 nitrate (B), SSCL02448 nitrate (C), or rhG-CSF (D). Neutrophil (A-D), lymphocyte (panel E), monocyte (panel F), RBC (panel G), and platelet (panel H) counts were measured in peripheral blood. Peripheral blood cells were collected on day –2 and days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. On days 1, 2, 3 and 4, they were collected 8 hours after each administration. Other details were as described in the legend to Figure 4.

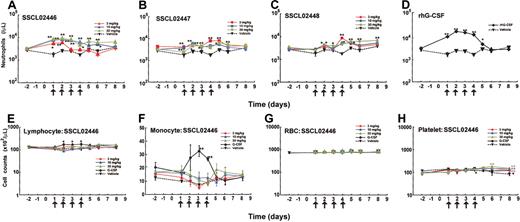

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 increase neutrophil levels in CPA-treated rats

As G-CSF is currently used to treat patients with neutropenia, we tested whether the novel compounds were also effective in the model neutropenic CD rats. We first determined that the minimum dose of CPA that reduced neutrophil numbers was 25 mg/kg in male CD rats (data not shown). Male CD rats were pretreated intraperitoneally with this dose on day 0. After that, SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 were administered subcutaneously once daily for 4 days. There was a dramatic increase in circulating neutrophils that continued until day 8 (Figure 6A-C). Again, SSCL02446 was the most effective of the 3 compounds, inducing a 7- to 8-fold rise in neutrophil counts on day 2. The rhG-CSF also induced granulopoiesis (Figure 6D), as reported previously.26 Cytologic analysis revealed mature neutrophils in the blood of rats treated with each of the small compounds (data not shown).

Effect of repeated administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in neutropenic CD rats. Male CD rats were injected intraperitoneally with 25 mg/kg CPA on day 0 (arrowhead), and thereafter treated subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (panel A), SSCL02447 nitrate (panel B), SSCL02448 nitrate (panel C), or rhG-CSF (panel D) on 4 consecutive days (days 1-4), and neutrophil counts were measured in peripheral blood. The arrows indicate the times of administration of small compounds and rhG-CSF. On day –2 and days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8, peripheral blood cells were collected. On days 1, 2, 3, and 4, they were collected 8 hours after each administration. Each point represents the mean of counts on 4 or 5 rats ± SEM. Blood smears from each group were stained with Diff Quik, and differential counts were performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Significant differences (*P < .05; **P < .01) from vehicle control were assessed by Dunnett test.

Effect of repeated administration of the small compounds on peripheral blood cell levels in neutropenic CD rats. Male CD rats were injected intraperitoneally with 25 mg/kg CPA on day 0 (arrowhead), and thereafter treated subcutaneously with SSCL02446 nitrate (panel A), SSCL02447 nitrate (panel B), SSCL02448 nitrate (panel C), or rhG-CSF (panel D) on 4 consecutive days (days 1-4), and neutrophil counts were measured in peripheral blood. The arrows indicate the times of administration of small compounds and rhG-CSF. On day –2 and days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8, peripheral blood cells were collected. On days 1, 2, 3, and 4, they were collected 8 hours after each administration. Each point represents the mean of counts on 4 or 5 rats ± SEM. Blood smears from each group were stained with Diff Quik, and differential counts were performed as described in “Materials and methods.” Significant differences (*P < .05; **P < .01) from vehicle control were assessed by Dunnett test.

Discussion

Small nonpeptidyl compounds that mimic human G-CSF

G-CSF is widely used to treat or prevent neutropenia in a variety of clinical settings. In addition to its well-characterized ability to induce neutrophil production, G-CSF is a potent inducer of neutrophil release from bone marrow. A previous study showed that a nonpeptidyl mimic of G-CSF, SB247646, induced proliferation through the G-CSF receptor and mediated neutrophil release from the bone marrow in mice though not in humans.13 However, the murine G-CSF receptor sequence required for SB247464 activity is distinct from that required for G-CSF binding. It is therefore important to find small nonpeptidyl compounds that can mimic human G-CSF in vivo. In the present study, we identified 3 synthetic small compounds that had proliferative activity among about 10 000 compounds screened (Figure 1A).

It is interesting to consider the structure of these compounds: SB247464 has 2-fold rotational symmetry, which is compatible with its functioning as a ligand to dimerize G-CSF receptors.13 On the other hand, SSCL02446 to SSCL02448, which are imidazole derivatives with long alkoxy chains, have asymmetric structures. One asymmetrical compound, TM41, has been shown to have activity equivalent to the native ligand, thrombopoietin.27 Evidently, several properties are required of an alternative ligand: to induce a conformational change of the receptor, which then induces receptor-receptor interaction, and to induce a cascade of cellular events that ultimately activate STATs and MAPK, which regulate gene expression and stimulate cell growth or other cellular changes. We have shown here that SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 induce proliferation and bring about the phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in BAF/GCSFR and in normal human neutrophils (Figure 2). The fact that these compounds stimulate early events in the G-CSF signal transduction pathway and that only the G-CSF–dependent cell line can respond to both G-CSF and these small compounds indicates that SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 act through the receptor. However, the precise mechanism by which these small compounds interact with G-CSF receptor is unclear, and these issues are currently under investigation.

SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 stimulate in vitro and in vivo granulopoiesis

G-CSF normally acts on granulocyte precursor cells in the bone marrow, promoting their proliferation and differentiation. SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 were active in the primary colony-forming assay (Figure 3). However, the colonies formed in response to the 3 novel compounds appeared uniformly smaller than those induced by rhG-CSF (data not shown). This suggests that terminal differentiation is induced after fewer divisions, or that the target cell is further along the myeloid differentiation lineage than the CFU-GM target of G-CSF. SB247464 has previously been shown to have a similar effect.13

We tested the in vivo efficacy of SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 in normal and CPA-induced neutropenic rats. Single subcutaneous administration of SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 increased peripheral blood neutrophils (Figure 4). Neutrophil counts increased 3-fold within 10 hours and then declined, whereas stimulation of neutrophil counts by rhG-CSF was maintained for 24 hours. Presumably, the novel compounds are cleared more rapidly from the circulation. The response to SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 is too rapid to be due to production of neutrophils from bone marrow progenitor cells; instead they probably stimulate release of preformed neutrophils from the bone marrow cavity or other storage sites, such as blood vessels.

Multiple administrations of SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 over 4 days also resulted in induction of neutrophil release (Figure 5). No significant changes in lymphocyte counts were observed with SSCL02446 (Figure 5).

CPA is an alkylating agent that is used in chemotherapy against leukemia and neoplasms, but one of its major side effects is myelosuppression due to damage to hematopoietic stem cells and precursor cells and to the hematopoietic microenvironment.28-33 Administration of SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 over 4 days to CPA-induced neutropenic rats caused a dramatic increase in neutrophil count that continued until day 8 (Figure 6). Again, SSCL02446 was the most effective of the 3 compounds. Although it was previously shown that repeated administration of SB247464 elevated peripheral neutrophil counts in normal mice, the effect on neutropenic mice was not examined.13 Thus, the present study provides the first evidence of a granulopoietic effect of small nonpeptidyl G-CSF–mimetics.

SSCL02446 was the most potent of the 3 compounds tested; probably because of differences in solubility in the vehicle solution, saline containing 1% DMSO. SSCL02446 is more soluble than SSCL02447 or SSCL02448, since it has the shortest alkoxy chain (Figure 1A) and thus may be more rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream after subcutaneous administration. Neutrophils are released from bone marrow in a regulated fashion to maintain constant numbers and to combat infection. Despite its clinical and biologic importance, the mechanism that regulates neutrophil release from bone marrow is poorly understood. Recent evidence indicates that G-CSF–induced G-CSF receptor signaling maintains basal levels of circulating neutrophils largely by regulating their release from the bone marrow.34 The segment of the G-CSF receptor that mediates neutrophil release corresponds to the membrane-proximal 87 amino acids. Furthermore, this region is sufficient to activate JAK and Src family tyrosine kinases, the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway, and some components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.5,35,36

Cytokines (G-CSF, EPO, IL-2, interferon-β [IFN-β], insulin, and so on) are widely used clinically as useful pharmaceutic agents. The small nonpeptidyl compounds that mimic the corresponding protein should be considered as the possible next generation of pharmaceutic agents.

Overall, our studies suggest that SSCL02446 to SSCL02448, small, nonpeptidyl compounds, are capable of mimicking the in vitro and in vivo function of G-CSF: namely, the activation of STAT3 and MAPK and induction of neutrophil release from the bone marrow. G-CSF is currently being used clinically in the following capacities: (1) to reduce the incidence of infection in patients receiving chemotherapy for nonlymphoid malignancies12 ; (2) to reduce neutropenia after bone marrow transplantation; (3) to reduce neutropenia in patients with severe chronic neutropenia; (4) to mobilize hematopoietic progenitor cells into the peripheral blood for collection by leukapheresis; and (5) to reverse neutropenia in patients with AIDS. We believe that SSCL02446 to SSCL02448 are the first small nonpeptidyl compounds that mimic the activity of human G-CSF. SSCL02446 in particular may be useful as a substitute for peptidyl G-CSF.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 25, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2307.

Several of the authors (K.K., S.E., K.T., T.N., S.S., T.K.) are employed by the companies whose potential product was studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We are grateful to Dr R. Palacios, Dr M. Hatakeyama, and Dr T. Taniguchi for providing the BAF/B03 cells. We also thank Dr H. Hasegawa, M. Tokizawa and Y. Kaneko for synthesizing the compounds, and the members of the chemical compound synthetic laboratory for their invaluable comments.

![Figure 1. Structure and in vitro effects of the 3 active compounds and the related inactive compound. (A) The active compounds along with the related inactive compound are as follows: SSCL02446, 2-[5-chloro-2-(heptyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02447, 2-[5-chloro-2-(octyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02448, 2-[5-chloro-2-(nonyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; and SSCL02444: 2-[2-(2-fluorobenzyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-pentanol. (B) G-CSF–induced cell proliferation. The BAF/GCSFR cells were cultured for 48 hours with varying concentrations of rhG-CSF, SSCL02446, SSCL02447, SSCL02448, or SSCL02444. Cell proliferation was measured with WST-1/1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methyl sulfate (PMS) as substrate (n = 5; mean). Standard errors of the mean were less than 5% and were therefore omitted. (C) IL-3–dependent cell proliferation. BAF/B03 cells were cultured for 48 hours in media containing various concentrations of rmIL-3, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (D) EPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/EPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhEPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (E) TPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/TPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhTPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (F) IL-10–dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/IL10R cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhIL-10, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (G) IL-2–dependent cell proliferation. CTLL-2 cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium containing various concentrations of rmIL-2 or the small compounds.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/3/10.1182_blood-2003-07-2307/6/m_zh80030455900001.jpeg?Expires=1768413473&Signature=kUuUL1l-LvLZgvcLg5BnhQn8T~SIK3DCmGSUE6bFejdJoKVlKLACMoK0Si8wqTUA-WeK-IJRcMbp9e~giOEGgTDmC8xHf-Qe~Qlonzq0satX2cB-A7XCuAYdh9uT5Iv-gunK8w3iQoq0aZUWu-PglvNF-2iT7FIn04fzLa2VETZ6KnuVC-S8LY2G7sihQ6WjZEa0WNH6rIgMR6kkDlUzQ6cBV07SqvdfZeral3ijpxM0qWZzbkJVP77ImSfL4G-DM0VlrGQ1vicQAqoSsQvLKt6n3DdPh1fr9cWfsoE9Or4m~a8vcfflgZSBP01b5FVdH4zof2RBzyI-~u4w6SmqLQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Structure and in vitro effects of the 3 active compounds and the related inactive compound. (A) The active compounds along with the related inactive compound are as follows: SSCL02446, 2-[5-chloro-2-(heptyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02447, 2-[5-chloro-2-(octyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; SSCL02448, 2-[5-chloro-2-(nonyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-propanol; and SSCL02444: 2-[2-(2-fluorobenzyloxy)phenyl]-1-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)-2-pentanol. (B) G-CSF–induced cell proliferation. The BAF/GCSFR cells were cultured for 48 hours with varying concentrations of rhG-CSF, SSCL02446, SSCL02447, SSCL02448, or SSCL02444. Cell proliferation was measured with WST-1/1-methoxy-5-methylphenazinium methyl sulfate (PMS) as substrate (n = 5; mean). Standard errors of the mean were less than 5% and were therefore omitted. (C) IL-3–dependent cell proliferation. BAF/B03 cells were cultured for 48 hours in media containing various concentrations of rmIL-3, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (D) EPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/EPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhEPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (E) TPO-dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/TPOR cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhTPO, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (F) IL-10–dependent cell proliferation. The BAF/IL10R cell line was cultured for 48 hours with various concentrations of rhIL-10, rhG-CSF, or the small compounds. (G) IL-2–dependent cell proliferation. CTLL-2 cells were cultured for 48 hours in medium containing various concentrations of rmIL-2 or the small compounds.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/103/3/10.1182_blood-2003-07-2307/6/m_zh80030455900001.jpeg?Expires=1768413474&Signature=pZMmmvACRCBHIEQIDxsbU-JPODx0M-MCFDxFu8T~sWUqS1QwCzSe7MNJJR~1D3QYCbPCCpxZvQExgl1Po5YBs4AaTqFFDBoSMegHxUgMcWB3eWDmWPBAQXtYoB7IzQ5vwsxwZvOs19iJGdBDKBa2k4cLb7aio9sjpe~GR-CXloCR0p3HkeY9OfREfuPgE6lRPR~Mp0pnVYVkq8RdkqHNnlQ6xvpRtKG52OsGQjdOC2F21amExpnDfECVRYn11mrVgqWAMPSccwSZ6BTQTsdNY5JQsFN5Ykz1gxFP6uQWvvUTzSjTcZuoRxj4~4vrFnkA2BB6ts1leuX4iTF5brV2sg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)