Abstract

Treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) has evolved over the last 20 years in response to our increased understanding of the pathophysiology of this complex immune disorder. New treatments in development have taken advantage of our evolving understanding of the biology of this disease to target new mechanisms and expand the available ways in which to approach patients with this disorder. This review focuses on novel therapeutics in the ITP pipeline and discusses the pathophysiology of ITP that has led to their development.

Learning Objectives

Understand how new insights into the pathophysiology of ITP have led to novel drug development

Describe new therapies in clinical trials for treatment of ITP and their potential role in disease management

CLINICAL CASE

A 24-year-old man diagnosed with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) approximately 15 months ago presents for a follow-up visit for his chronic ITP. He has had previously documented responses to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and corticosteroids but has not had a sustained response to either treatment, despite platelet counts that increase to >150 × 109/L with treatment. His platelet count has remained <20 × 109/L even with a treatment trial with two different oral thrombopoietin receptor agonists. He was unable to tolerate fostamatinib due to hypertension and has been unwilling to take weekly subcutaneous injections. He did not respond to rituximab and is not interested in splenectomy. While he has minimal bleeding symptoms at baseline even with severe thrombocytopenia, he prioritizes an active lifestyle and participates in competitive downhill skiing to maintain his mental health and well- being. What other treatment options are emerging or available, and what other treatments could be considered?

Introduction

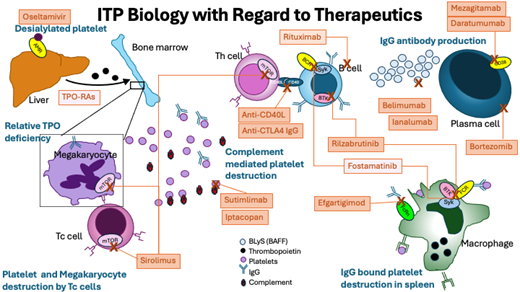

Treatment for ITP has continued to evolve since the first descriptions of splenectomy in 1916. Corticosteroids for the treatment of ITP were introduced in 1950,1 and IVIg for pediatric ITP2 emerged as a treatment in 1981. As the search for viable nonsurgical treatment options continued, the use of immunomodulatory therapies available for other indications to manage ITP were explored, leading to the use of azathioprine, dapsone, vincristine, and mycophenolate mofetil. With the advent of new treatments, IVIg and corticosteroids have moved to play more of a role for rescue therapy, while thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs), rituximab, fostamatinib, and splenectomy play more of a role in the daily management of longer-lasting disease. More recent studies of the pathophysiology of ITP have determined that suboptimal platelet production plays a key role in the thrombocytopenia, leading to the development of the multiple TPO-RAs: rhTPO, romiplostim, eltrombopag, hetrombopag, and avatrombopag, which have been approved for use in various countries for treatment of chronic ITP in adults3-5 and even in children.6 Further insights into different pathophysiologic mechanisms have led to trials of other medications exploring novel immune pathways. These include blocking antibody reuptake mechanisms, inhibiting other immune cells, including B and T cells, and even targeting complement to affect the balance between platelet production and destruction and improve platelet counts.7 Further, ongoing clinical trials and input from patient advocacy organizations have shifted the focus in therapeutic management from only looking at a single parameter (the patient's platelet count) to understanding the impact of ITP on the patient and determining the best course of therapy using shared decision-making. This review will describe the novel therapies in late clinical trials (Table 1) as well as those currently in development in relation to their proposed mechanism of action in ITP (Figure 1).

Pathophysiology of ITP and key therapeutic targets. AMR, Ashwell-Morell receptor; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; BCR, B-cell receptor; BLyS, B lymphocyte stimulator; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; FCR, Fc receptor; FcRn, neonatal Fc receptor; IgG, immunoglobulin; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Tc, cytotoxic T cell; Th, helper T cell. Drugs in light orange boxes are FDA approved for ITP and not discussed in this article but are shown for completeness; they include fostamatinib and TPO-RAs, thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Rituximab is shown and has sufficient literature to support its use, although it does not have FDA or other regulatory indication for use in ITP.

Pathophysiology of ITP and key therapeutic targets. AMR, Ashwell-Morell receptor; BAFF, B-cell activating factor; BCR, B-cell receptor; BLyS, B lymphocyte stimulator; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; FCR, Fc receptor; FcRn, neonatal Fc receptor; IgG, immunoglobulin; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Tc, cytotoxic T cell; Th, helper T cell. Drugs in light orange boxes are FDA approved for ITP and not discussed in this article but are shown for completeness; they include fostamatinib and TPO-RAs, thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Rituximab is shown and has sufficient literature to support its use, although it does not have FDA or other regulatory indication for use in ITP.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibition

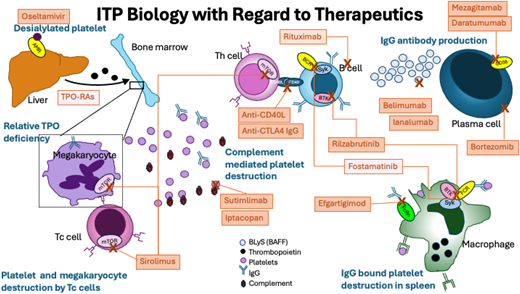

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) is expressed widely, and because it is a downstream mediator of the B-cell receptor, it plays a role in B-cell maturation and differentiation affecting antibody production and likely has a role in Fcg receptor function.8 Several BTK inhibitors have been created since the initial development of ibrutinib for B-cell malignancy.9 Rilzabrutinib (PRN1008, Sanofi) (Figure 2) was developed to treat immune diseases as an oral, reversible inhibitor of BTK. In an open-label, phase 1/2 clinical trial of 60 patients with refractory ITP, 40% of patients had a platelet count response (defined as platelet count >50 × 109/L × 2 or doubling of baseline count), with patients meeting the primary endpoint spending 65% of the study with platelet count >50 × 109/L and overall patients spending a mean of 29% of weeks of the study with platelet count >50 × 109/L.10 There were no treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or higher and no serious adverse events, and the regimen was well tolerated in a highly pretreated group of patients. The long-term extension study results of the initial phase 1/2 study were recently published and demonstrated long-term responses without any new safety signals.11 The dose brought forward to the phase 3 clinical trial was 400 mg BID, which is currently being studied in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults and pediatric patients (aged >12 years) that recently completed enrollment of adults (NCT04562766).

Structure of rilzabrutinib and proposed function in ITP. Mechanism of action of rilzabrutinib in ITP. Reproduced from Kuter et al. Rilzabrutinib versus placebo in adults and adolescents with persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia: LUNA 3 phase III study. Ther Adv Hematol. 2023;14. doi:10.1177/20406207231205431.

Structure of rilzabrutinib and proposed function in ITP. Mechanism of action of rilzabrutinib in ITP. Reproduced from Kuter et al. Rilzabrutinib versus placebo in adults and adolescents with persistent or chronic immune thrombocytopenia: LUNA 3 phase III study. Ther Adv Hematol. 2023;14. doi:10.1177/20406207231205431.

One major potential concern of BTK inhibition in ITP is the known effect of currently approved BTK inhibitors on platelet function.12 Although the effects of this inhibition on primary hemostasis are still unclear,13 there is a reported risk of gastrointestinal bleeding,14 which would seem to preclude use in severely thrombocytopenic patients. However, rilzabrutinib has been developed to minimize the impact on platelet function through more targeted kinase inhibition and has been shown not to significantly affect platelet function.

Neonatal Fc receptor blockade

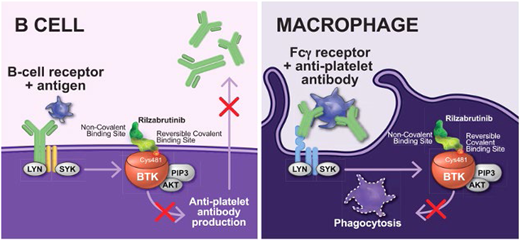

The predominant autoantibodies in ITP are immunoglobulin G (IgG), which bind most often to the two most prevalent platelet glycoprotein receptors: the fibrinogen receptor (GPIIb/IIIa) and the von Willebrand factor receptor (GPIb/IX).15 These autoantibodies may bind to megakaryocytes, leading to destruction within the bone marrow and/or decreased proliferation,16 and bind to platelets, which results in platelet uptake by splenic macrophages, leads to complement mediated lysis, and causes platelet desialylation or directs platelet apoptosis (Figure 1). IgG levels are naturally controlled through the function of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which takes up maternal IgG in utero,17 then continues to work to recycle IgG in circulation, prolonging the half-life of this important immunologic molecule.18 Two neonatal FcRn inhibitors have been developed and examined in immunologic disease: efgartigimod and rozanolixizumab (Figure 3). Efgartigimod alpha (Vyvgart, argenx SE) is an engineered human IgG1 antibody Fc-fragment designed to preferentially bind to FcRn and prevent the uptake and recycling of IgG. It is currently approved for use in treatment of myasthenia gravis in the United States and European Union.

Mechanism of action of neonatal Fc receptors in maintaining IgG levels. (A) Protection of IgG from degradation, and (B) how FcRn inhibitors disrupt IgG recycling. In (A), IgG is ingested by pinocytosis. Pinocytotic vesicles fuse with acidic endosomes in which FcRn can bind IgG. Excess unbound IgG and other proteins enter the lysosome and are degraded. IgG bound to FcRn is retained and released by exocytosis. In (B), FcRn inhibitors bind to FcRn in both neutral and acidic environments. In the presence of FcRn inhibitors, ingested IgG is unable to bind to FcRn; the unbound IgG enters the lysosome and is degraded. For illustrative purposes, albumin binding is not shown. Reproduced from Patel and Bussel 37 with permission under CC license.

Mechanism of action of neonatal Fc receptors in maintaining IgG levels. (A) Protection of IgG from degradation, and (B) how FcRn inhibitors disrupt IgG recycling. In (A), IgG is ingested by pinocytosis. Pinocytotic vesicles fuse with acidic endosomes in which FcRn can bind IgG. Excess unbound IgG and other proteins enter the lysosome and are degraded. IgG bound to FcRn is retained and released by exocytosis. In (B), FcRn inhibitors bind to FcRn in both neutral and acidic environments. In the presence of FcRn inhibitors, ingested IgG is unable to bind to FcRn; the unbound IgG enters the lysosome and is degraded. For illustrative purposes, albumin binding is not shown. Reproduced from Patel and Bussel 37 with permission under CC license.

The phase 2 trial (NCT03102593)19 in patients with primary ITP investigated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated that in the 38 randomized patients, intravenous infusion of efgartigimod was well tolerated, with 1 case of pneumonia during the open-label treatment period and other no serious adverse events attributable to efgartigimod. The study was not powered to address a predefined primary endpoint.

Patients were assigned to 1 of 2 dose levels of efgartigimod (5 or 10 mg/kg) dosed weekly for 4 weeks; in both treatment groups, platelet count responses were achieved in more patients in the treatment group than in the placebo group, with 38% of active-treatment patients achieving a platelet count >50 × 109/L for more than 10 cumulative days compared to the placebo group (0%). More patients receiving efgartigimod had improvement in platelet count (>50 on 2 more measures; 46%) vs placebo (25%). The international working group definition of response (platelet count 30-100 × 109/L and a doubling from baseline confirmed on at least 2 consecutive counts ≥7 days apart) was met in 38.5% of patients in each treatment group and 16.7% of patients in the placebo group. In addition, in both efgartigimod groups, there was a reduction in bleeding events (from 46.2% to 7.7% in the 5 mg/kg group; 38.5% to 7.7% in the 10 mg/kg group) compared to placebo (33.3% to 25%).

There was 1 patient who experienced worsening of ITP, leading to drug discontinuation considered unlikely related to efgartigimod (grade 4), There was 1 patient with efgartigimod and 2 with placebo who experienced at least 1 event that study investigators considered treatment related. The proposed mechanism of action of FcRn blockade was confirmed by a reduction of total immunoglobulin levels in both groups of patients getting efgartigimod, with a maximum mean reduction of about 60% in both groups. Platelet-specific antibodies also decreased by about 40% in 66.7% to 70% of patients receiving efgartigimod.

The phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (ADVANCE SC: NCT04687072 and ADVANCE IV:NCT04188379) have been completed and reported in abstract form but are not yet peer reviewed.

Rozanolixizumab (Rystiggo, UCB) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for myasthenia gravis as well and was evaluated in a phase 2, open-label study as a subcutaneous infusion in persistent or chronic ITP patients (NCT02718716) in a trial that was recently completed with results published.20 This study enrolled 65 patients. The primary objective was safety, with a secondary objective of efficacy. The most common treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were headache, vomiting, and diarrhea. They were all mild. There were no treatment- related severe AEs, and the 4 severe AEs reported were all bleeding or thrombocytopenia related to the primary diagnosis. There were multiple dosing cohorts in this study including single and multiple dose cohorts at multiple dosing levels, and dose-dependent responses were observed with >50% platelet count ≥50 × 109/L in the highest single dose cohorts and 7% to 27% in the lower, multiple dose cohorts. Two phase 3 trials were launched. However, both were terminated in 2022 by UCB, which decided not to pursue further the ITP indication.

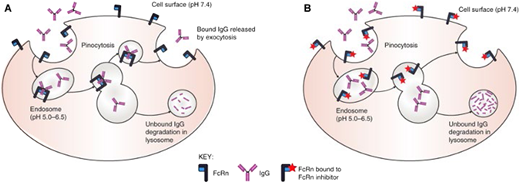

Complement inhibition

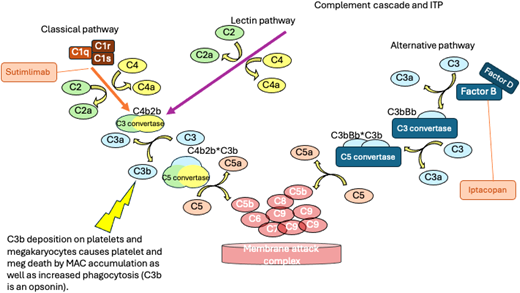

One mechanism of platelet destruction in ITP that has emerged in recent years as a potential contributor to thrombocytopenia in a subset of patients and as a potential mechanism for targeting by novel therapeutics is the observation that glycoprotein- associated IgG on platelets can fix complement, resulting in accumulation of C3b on the platelet membrane that can contribute to platelet phagocytosis21 and to platelet destruction by the membrane attack complex. In addition, in ITP, deposition on platelet membranes appears to activate the classical complement pathway, leading to generation of C3 and activation of autoreactive B cells (Figure 4).22

The complement cascade and the locations where inhibitors being studied in ITP act. The places where C3b is generated are noted. C3b is a potent opsonin increasing phagocytosis of platelets. Deposition of complement on platelets and megakaryocytes leads to the formation of the terminal complement complex (membrane attack complex) and cell death.

The complement cascade and the locations where inhibitors being studied in ITP act. The places where C3b is generated are noted. C3b is a potent opsonin increasing phagocytosis of platelets. Deposition of complement on platelets and megakaryocytes leads to the formation of the terminal complement complex (membrane attack complex) and cell death.

The observation of complement deposition on platelets of patients with ITP led to the development of sutimlimab (Enjaymo, Sanofi), which is a humanized monoclonal anti-C1s antibody. By preventing complement activation at C1 (Figure 4), the lectin and alternative pathways are left intact to allow for ongoing normal immune activation, but the deposition of C3 on the surface of platelets is reduced, decreasing B-cell activation.22

Sutimlimab has undergone a phase 1 open-label study (NCT03275454) with 12 adults with chronic, refractory ITP. Patients received treatment for 11 doses (21 weeks) followed by a 9-week washout period (part A) and then could continue in the extension period for additional treatment (part B); the primary outcome was safety and tolerability of multiple doses of sutimlimab. There was 1 serious adverse event of migraine in part A and 1 of diverticulitis in part B, and no adverse events led to discontinuation. The efficacy objective was to evaluate the change in platelet count in response to treatment with secondary endpoints of complete response (CR), duration of response, and time to response. In 12 patients, 42% showed an overall platelet count response concomitant with evidence of complement inhibition with sutimlimab (given at 6.5 g IV every 2 weeks, if <75 kg, or 7.5 g, if >75 kg). Platelet counts dropped in patients who responded during planned washout.23 Importantly, patient responses in this early study were rapid, with 33% of patients demonstrating a response (by International Working Group definition) after 24 hours and 17% with CR at 24 hours, suggesting that complement inhibition may be a novel therapeutic target with very rapid onset of action that could be particularly useful in patients with severe thrombocytopenia and bleeding.

Iptacopan (LNP023, Novartis) is an oral factor B inhibitor (Figure 4). Factor B functions by reducing downstream activation of the alternative pathway and the amount of active C3 convertase and thereby decreasing the generation of C3a, C5a, and membrane attack complexes. This approach does not affect the classical and lectin pathways of complement activation. Iptacopan has been studied in other immune disorders where complement activation plays a key role, including PNH24 and nephrotic syndrome,25 where key side effects include headache and abdominal pain. There is a phase 2 study (NCT05086744) of iptacopan in autoimmune hematologic disease open for patients with cold agglutinin disease and ITP, although the study is not currently enrolling patients.

Plasma cell depletion and alternative ways to decrease autoantibody production

Autoantibodies have been known to play an essential role in the development of ITP for a long time. B-cell directed therapies have shown efficacy in ITP starting with rituximab26 and form the basis for some of the novel therapies currently under investigation, including BTK inhibition and complement blockade. However, these therapies do not target nondividing memory cells such as plasma cells. The efficacy of splenectomy even after rituximab suggests that plasma cells play a role in ITP biology and are a potential target for novel therapies (Figure 1).

Targeting CD 38: CD38 (cyclic ADP ribose hydrolase) is found on many immune cells including NK cells, B cells, and T cells but is highly expressed on plasma cells and was initially targeted for therapies in multiple myeloma.27 Daratumumab (Darzalex, Janssen) is a monoclonal anti-CD38 antibody approved for treatment of multiple myeloma that is currently being investigated in an open-label phase 2 dose-escalation study in primary ITP in adults (NCT04703621). Mezagitamab (TAK-079, Takeda) is a fully humanized monoclonal anti-CD38 antibody that is also under investigation in ITP but in a randomized phase 2 study (NCT0427924). Both antibodies are administered as weekly subcutaneous injections.

Targeting the proteosome: In looking for plasma cell targeting therapies, the field of multiple myeloma presents fertile ground for ITP discovery. Bortezomib (Velcade, Millennium) is a proteosome inhibitor developed for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma. Several case reports and a small case series have examined the efficacy of bortezomib in ITP patients,28-30 and there are currently 2 clinical trials recruiting in China, a phase 2, open-label, single-arm study of IV bortezomib (NCT03013114) and a phase 3 randomized trial of bortezomib + rituximab vs rituximab (NCT03443570).

Targeting B-cell activating factor (BAFF): Ianalumab (VAY736, Novartis) is a monoclonal antibody targeting BAFF (also known as B lymphocyte stimulator or BLyS); it is in development for autoimmune hepatitis, multiple sclerosis, Sjogren's syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis. Because BAFF is required for B-cell proliferation (Figure 1), ianalumab is expected to decrease total autoantibody production, leading to downstream increased platelet counts. There is currently a phase 2 open-label, single-arm study evaluating efficacy and safety in primary ITP patients who have failed at least corticosteroids and TPO-RA (NCT05885555) as well 2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase 3 studies of ianalumab: 1 vs placebo in addition to corticosteroids in newly diagnosed patients (NCT05653349) and 1 vs placebo in addition to TPO-RA in patients who fail corticosteroids (NCT05653219). An alternative drug, belimumab, which is also a monoclonal anti-BAFF antibody, is being studied in a phase 3 randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing belimumab vs placebo plus rituximab in patients with persistent or chronic ITP (NCT05338190). Both of these medications are administered subcutaneously (ianalumab and belimumab).

The results of a prospective, phase 2b trial using belimumab intravenously in combination with rituximab (NCT03154385) were published in 2021 by investigators in France.31 This prospective, open-label study enrolled 15 patients (median age of 50 years; 12/15 female) who received 1000 mg rituximab IV × 2 doses given 2 weeks apart and belimumab IV at 10 mg/kg × 5 doses given week 0 + 2 days, week 2 + 2 days and then again on week 4, 8, and 12. In this study, 80% (95% CI 52-96) of patients met the primary outcome, which was an overall response at week 52 (CR + response) with 66.7% ((5% CI 38-88) achieving a CR defined as platelet count >100 × 109/L corresponding to 10/15 patients. Response was defined according to the International Working Group definition. Secondary outcomes included responses at earlier time points, bleeding events, hypogammaglobulinemia degree and duration, severe infections, and gamma globulin subclass levels during the study. There were 31 adverse events reported during the study, 5 of which were related to infusion of rituximab (grade 1). Overall, 26 of the adverse events were grade 1, with 8 possibly related to treatment (2 = bronchitis; 3 = nasopharyngitis; 1 = arthralgia; 1 = cystitis; 1 = candid vulvovaginitis). One grade 2 event of serum sickness and moderate arthralgia and rash occurred with second rituximab infusion. While there was a decrease in serum IgG and IgM titers between baseline and week 24 (median 0.98 g/L IgG and 0.42 g/L IgM), only 1 patient experienced moderate hypogammaglobulinemia (serum Ig titers 4.9 g/L and IgG 4.7 g/L) and recovered by week 24. The study supported the development of the further phase 3 studies.

Other mechanisms previously studied or under investigation

AntiCD40 ligand: CD40 ligand (CD154) is expressed on activated CD4+ T cells, platelets, and endothelial cells and interacts with CD40 on B cells in an essential interaction required for immunoglobulin class switching and the T-cell dependent humoral response. Blocking CD40 ligand in animal models has been shown to decrease autoantibody production (REF), and in 2008, an open-label phase 1-2 pilot study of 2 monoclonal anti-CD40 ligand antibodies in 46 patients (≥16 years of age with chronic ITP and refractory to several conventional therapies with platelet count ≤30 × 109/L) was reported.32 Two different monoclonal antibodies were evaluated/reported in the same study: an initial monoclonal antibody was studied in 15 patients (hu5c8), and toralizumab was studied in 31 patients at doses of 5-20 mg/kg every 2 weeks for a total of 16 weeks. The primary platelet outcome was an increase in platelet count >20 × 109/L from baseline, giving a sustained platelet count ≥30 × 109/L for at least a month. A complete response was defined as a platelet count >150 × 109/L on at least 2 occasions 1 week apart, and a partial response was platelet count >50 × 109/L. There was a 16% response rate in the toralizumab arm. One patient died during the study of intracranial hemorrhage 18 hours after infusion of the study drug; there were no adverse events related to study medications and no thromboembolic events. The development of thromboembolic events in animal models and then subsequently in clinical trials in multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease led to discontinuation of toralizumab development, but novel drugs targeting this mechanism are in development.

Oseltamivir: Recent work focused on platelet glycoprotein modification as a result of the immune response in ITP has highlighted the important role of the liver and the Ashwell-Morell receptor in platelet lifespan. Anti-GPIb alpha antibodies induce platelet activation and result in loss of platelet surface sialylation (desialylation), which is mediated by neuraminidase.33 Oseltamivir is a neuraminidase inhibitor developed to treat influenza infection and has been reported in a few case series and 1 series with literature review.34 Outcomes in these studies vary, as do the ages of patients (from 5 years to 79 years of age) and the prior therapies and response rates (from 40% to 100% with the caveat that the 100% responses are all in single case reports). Responses to the antiviral are between 5 and 30 days after starting antiviral therapy, and without randomized trials, the data are hard to interpret. However, the drug has been well tolerated (generally 75 mg twice daily, orally for 5 days) without reported side effects in these very small studies of 1-10 patients.

Sirolimus: An inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), sirolimus (rapamycin) was initially demonstrated to be highly effective in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) with FAS mutations or other associated molecular changes.35 A subsequent multicenter, open-label, prospective study in children and young adults with refractory autoimmune cytopenias (NCT00392951) reported the responses to sirolimus of 30 patients who had previously failed multiple other lines of treatment.36 In this cohort, 12 patients had ALPS, 4 of the remaining patients had refractory ITP, while 8 of them had non-ALPS-related multilineage autoimmune cytopenias (Evans syndrome), 2 had lupus, 2 had common variable immunodeficiency with autoimmune cytopenias, and 2 had autoimmune hemolytic anemia. In this mixed population, the best responses (resolution of cytopenias) were in patients with multilineage cytopenias with or without ALPS, whereas single-lineage cytopenias had the least response. In patients with ALPS, 11/12 patients experienced a hematologic CR within 3 months of starting (CR defined as normalization of hematologic parameters) and 8/12 non-ALPS patients had multilineage cytopenias. The most common toxicity was grade 1 or 2 mucositis (10/30 patients) most often within the first 3 months of initiating treatment. This study suggested that in patients with secondary autoimmune cytopenias, sirolimus is potentially an effective therapy, especially in the pediatric population. Since then, several additional studies have shown similar efficacy in multilineage cytopenias, with some even demonstrating markedly better efficacy than the first study in single-lineage cytopenias (PMID 28267088, 32771553, 37967535, 38741164).

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

While this young adult is relatively asymptomatic from a bleeding perspective, his thrombocytopenia is affecting his quality of life and his ability to participate in activities that are meaningful to him. As such, offering participation in a clinical trial evaluating one of the many novel therapeutics in development seems reasonable, and referral to a center with access to clinical trials is appropriate for discussion. By providing access and participation in clinical trials, we gain insights into novel therapies and pathophysiology and develop additional treatments for patients with ongoing ITP that has not responded to current therapy.

Future directions and conclusions

The world of ITP treatment is evolving rapidly with novel therapies targeting specific mechanisms of disease being developed to address the ongoing unmet need for treatments for many patients. Still unaddressed is the wide gap in available therapies for pediatric patients vs adults with ITP and the lack of understanding of the determinants of bleeding phenotype, especially in pediatric disease. While the strides we have made are certainly encouraging and offer hope to patients and families, there continues to be a need for more of an understanding of the biology of this disease, the features that define differences in patient responses, and the tools to predict best treatments before patients spend years cycling through therapies to find the one that “works.” Understanding which patients benefit from more aggressive therapies because of high bleeding risk vs those who can be managed with an approach geared more to addressing issues of quality of life is critical to developing the next generation of interventions in ITP.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Michele P. Lambert: membership on advisory board: Octapharma, Dova, Principia, Rigel, Argenx, PDSA, 22qSociety, and CdLS Foundation; consultancy: Novartis Dova, Principia, Argenx, Rigel, Sobi, Sanofi, Janssen; research funding: FWGBD, PDSA, NIH, Sysmex, Novartis, Principia, Argenx, Dova, Octapharma, Sanofi.

Off-label drug use

Michele P. Lambert: All of the medications and therapies discussed in this article are in clinical trials and not approved by the FDA for use in the manner discussed.