Abstract

Vascular malformations, which result from anomalies in angiogenesis, include capillary, lymphatic, venous, arteriovenous, and mixed malformations and affect specific vessel types. Historically, treatments such as sclerotherapy and surgery have shown limited efficacy in complicated cases. Most vascular malformations occur sporadically, but some can be inherited. They result from mutations similar to oncogenic alterations, activating pathways such as PI3K-AKT-mTOR or Ras-MAPK-ERK. Recognizing these parallels, we highlight the potential of targeted molecular inhibitors, repurposing anticancer drugs for the treatment of vascular malformations. This case-based review explores recent developments in precision medicine for slow-flow and fast-flow vascular malformation.

Learning Objectives

Understand the role of a detailed vascular malformation classification in the management of patients for an optimal therapeutic strategy

Highlight the importance of considering genomic analysis in any vascular malformation, as it may help to propose targeted therapies

Introduction

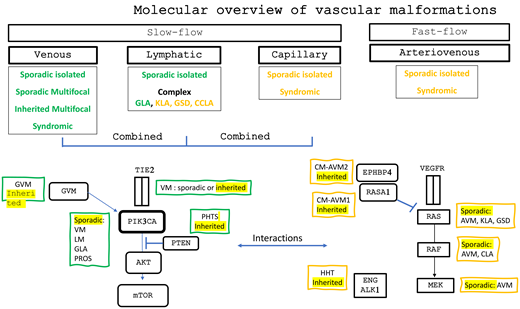

Vascular malformations result from defects during early vascular development, leading to abnormal vascular structures. These malformations are categorized according to the vessels affected and the flow speed: slow-flow malformations, including venous (VMs), capillary (CMs), lymphatic (LMs), and combined malformations, and fast-flow malformations, including arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). Most vascular malformations are congenital, generally present at birth, and expand over a lifetime. They have a significant impact on quality of life, causing chronic pain, deformities, and functional limitations. While surgery and sclerotherapy are primary treatment options, they are often insufficient or ineffective or not feasible in complex cases (Figure 1).1

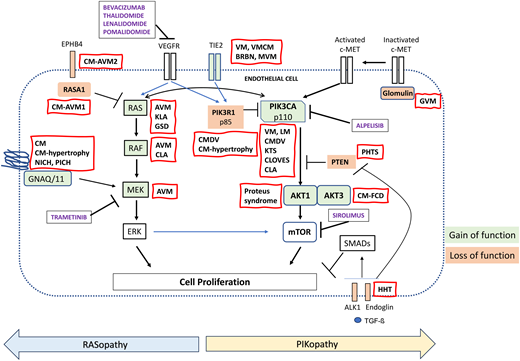

Brief overview of vascular malformation classification. CLOVES, congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies epidermal nevi and scoliosis; CLVM, capillary-lymphatic-venous malformations; CVM, capillary-venous malformation; KTS, Klippel- Trenaunay syndrome; LVM, lymphatic-venous malformations.

Brief overview of vascular malformation classification. CLOVES, congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies epidermal nevi and scoliosis; CLVM, capillary-lymphatic-venous malformations; CVM, capillary-venous malformation; KTS, Klippel- Trenaunay syndrome; LVM, lymphatic-venous malformations.

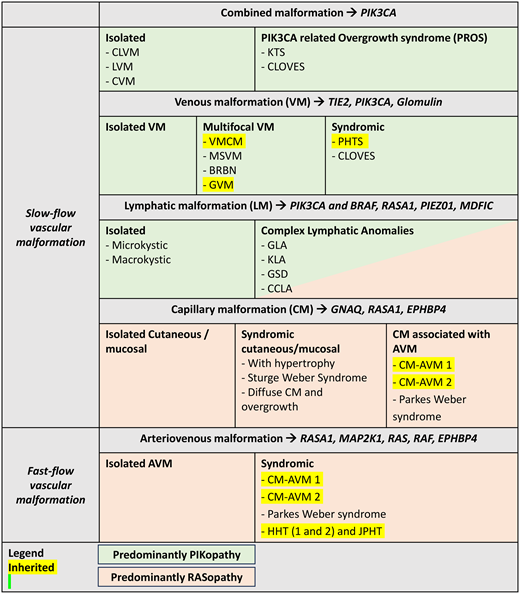

Two essential pathways regulate angiogenesis: the phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Binding of the growth factor angiopoietin (1 or 2) to TIE2 on endothelial cells (ECs) triggers the PI3K-AKT-mTOR cascade. PIK3R1 and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) negatively regulate this cascade by decreasing PI3K activity and activation of AKT. The MAPK pathway is induced by growth factors, cytokines, and G protein coupled receptor ligands that lead to the active form of guanosine triphosphate-bound Ras, which sequentially activates Raf and MAP extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (MEK1), resulting in nuclear translocation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1 and 2. Ras p21 protein activator 1 (RASA1), by converting guanosine triphosphate to guanosine diphosphate, renders Ras unable to phosphorylate Raf (Figure 2).2

Signaling pathways involved in vascular malformations. CLOVES , congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies epidermal nevi and scoliosis; KTS, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Signaling pathways involved in vascular malformations. CLOVES , congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies epidermal nevi and scoliosis; KTS, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

The majority of vascular malformations are isolated and noninherited, mainly caused by somatic gain-of- function (GOF) pathogenic variants that overactivate these pathways. However, a minority of vascular malformations are caused by inherited germline loss-of-function (LOF) pathogenic variants, mainly in tumor suppressor genes. In some malformations, a second LOF pathogenic variant in the same gene on the other chromosome pair is required to generate a complete localized LOF of the protein. Although the germline TIE2 pathogenic variants in inherited VM are GOF pathogenic variants, they also need a second hit to cause lesions. PIKopathies and Rasopathies include vascular defects in which the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and the MAPK cascades are affected, respectively (Figure 2). These pathogenic variants, shared by cancers, highlight the potential for repurposing anticancer agents for vascular malformations. Thus, correct classification of vascular malformations is crucial as specific molecular alterations may modify therapy (Table 1).

Pathogenic variants involved in vascular malformations and proposed targeted therapies

| . | Malformations . | Reported mutated gene . | Pathogenic variant type . | Target . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENOUS malformations | ||||

| Isolated | Sporadic VM | 60% TEK (L914F) 20% PIK3CA (E542-E545-H1047) | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| Multifocal | VMCM | TEK (R849W) | Germline GOF (second hit required) | |

| MVM | TEK (double mutation Y897C-R915C) | Mosaic GOF (second hit required) | ||

| BRBN | TEK (double mutations T1105N-T1106P and Y897F-R915L) | Somatic GOF | ||

| GVM | Glomulin | Germline LOF (second hit required) | Activation of PI3K downstream targets Inhibition of the TGF-ß signaling Increased protein ubiquitination | |

| LYMPHATIC malformations | ||||

| Isolated | Cystic LM | 80% PIK3CA (hot-spot E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| CLAs | GLA | 55% PIK3CA (hot-spot E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| GSD | KRAS | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK | |

| KLA | NRAS CBL | Mosaic GOF Mosaic LOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK Activation of tyrosine kinase receptors | |

| CCLA | EPHB4 | Germline LOF | Activation of Ras-RAF-MEK | |

| BRAF | Mosaic GOF | |||

| RASA1 | Somatic LOF | |||

| PIEZO1 | Germline LOF | |||

| MDFIC | Germline LOF | |||

| PIK3CA-related syndromes | ||||

| PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome | Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | PIK3CA (mostly hot spot: E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| CLOVES | PIK3CA (mostly non–hot spot) | |||

| CAPILLARY malformations | ||||

| Isolated | CM/SWS | GNAQ, GNA11 | Somatic GOF | Activation of PLCβ and ERK |

| CMDV | PIK3R1 PIK3CA (non–hot-spot mutations) | Somatic LOF Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR | |

| Association or multifocal | SWS | GNAQ, GNA11 | Somatic GOF | Activation of PLCβ and ERK |

| CM + cerebral anomalies and epilepsy | AKT3 | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR | |

| CM-AVM1 | RASA1 | Germline LOF (Second-Hit required) | Increased expression of RAS | |

| CM-AVM2 | EPHB4 | Germline LOF | Decreased expression of RASA1 | |

| ARTERIOVENOUS malformations | ||||

| Sporadic AVM | Sporadic extracranial AVM | MAP2K1 KRAS BRAF | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK |

| Syndromic HHT | HHT Juvenile polyposis HHT | ENG, ALK1, HHT3, HHT4 SMAD4 | Germline LOF | Increase activity of PI3K and decrease activity of PTEN |

| Syndromic PHTS | PHTS | PTEN | Germline LOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| . | Malformations . | Reported mutated gene . | Pathogenic variant type . | Target . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VENOUS malformations | ||||

| Isolated | Sporadic VM | 60% TEK (L914F) 20% PIK3CA (E542-E545-H1047) | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| Multifocal | VMCM | TEK (R849W) | Germline GOF (second hit required) | |

| MVM | TEK (double mutation Y897C-R915C) | Mosaic GOF (second hit required) | ||

| BRBN | TEK (double mutations T1105N-T1106P and Y897F-R915L) | Somatic GOF | ||

| GVM | Glomulin | Germline LOF (second hit required) | Activation of PI3K downstream targets Inhibition of the TGF-ß signaling Increased protein ubiquitination | |

| LYMPHATIC malformations | ||||

| Isolated | Cystic LM | 80% PIK3CA (hot-spot E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| CLAs | GLA | 55% PIK3CA (hot-spot E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| GSD | KRAS | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK | |

| KLA | NRAS CBL | Mosaic GOF Mosaic LOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK Activation of tyrosine kinase receptors | |

| CCLA | EPHB4 | Germline LOF | Activation of Ras-RAF-MEK | |

| BRAF | Mosaic GOF | |||

| RASA1 | Somatic LOF | |||

| PIEZO1 | Germline LOF | |||

| MDFIC | Germline LOF | |||

| PIK3CA-related syndromes | ||||

| PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome | Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | PIK3CA (mostly hot spot: E542-E545-H1047) | Mosaic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

| CLOVES | PIK3CA (mostly non–hot spot) | |||

| CAPILLARY malformations | ||||

| Isolated | CM/SWS | GNAQ, GNA11 | Somatic GOF | Activation of PLCβ and ERK |

| CMDV | PIK3R1 PIK3CA (non–hot-spot mutations) | Somatic LOF Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR | |

| Association or multifocal | SWS | GNAQ, GNA11 | Somatic GOF | Activation of PLCβ and ERK |

| CM + cerebral anomalies and epilepsy | AKT3 | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR | |

| CM-AVM1 | RASA1 | Germline LOF (Second-Hit required) | Increased expression of RAS | |

| CM-AVM2 | EPHB4 | Germline LOF | Decreased expression of RASA1 | |

| ARTERIOVENOUS malformations | ||||

| Sporadic AVM | Sporadic extracranial AVM | MAP2K1 KRAS BRAF | Somatic GOF | Direct activation of Ras-RAF-MEK |

| Syndromic HHT | HHT Juvenile polyposis HHT | ENG, ALK1, HHT3, HHT4 SMAD4 | Germline LOF | Increase activity of PI3K and decrease activity of PTEN |

| Syndromic PHTS | PHTS | PTEN | Germline LOF | Direct activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR |

CLOVES, congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies epidermal nevi and scoliosis; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MAP3K3, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 3.

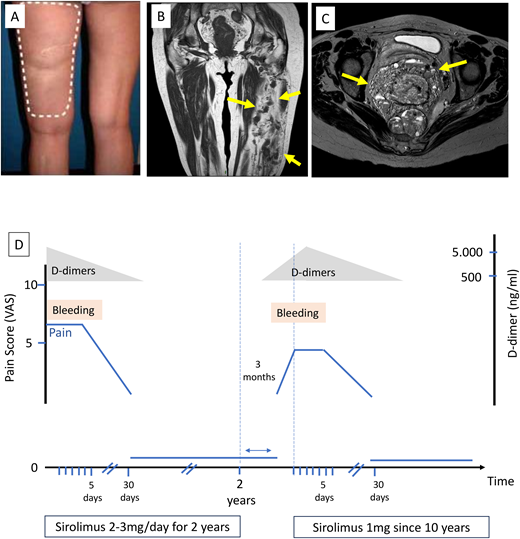

CLINICAL CASE

A 65-year-old woman has had a large lesion involving the entire left leg since birth, causing pain and swelling. She also had daily vaginal bleeding due to perineal involvement (Figure 3). D-dimer levels were very high, exceeding 5000 ng/mL, which is frequently observed in VM due to repeated thrombosis- thrombolysis cycles. Surgery was deemed unfeasible due to the extent of the lesions, and repeated sclerotherapies were not sufficient to control symptoms. Symptoms worsened over time with daily bleeding and chronic pain with a visual analogue score of around 6 out of 10 continuously and a daily exacerbation of up to 10 out of 10, requiring morphine-based treatment. There was no family history of vascular anomaly. There was no hypertrophy.

Clinical case. (A) Extensive bluish lesions on left lower limb; (B) magnetic resonance imaging showing extensive venous malformation in most of the muscles of the thigh (blue arrows); (C) magnetic resonance imaging showing involvement of the perineal area (blue arrows); (D) evolution of symptoms (bleeding and visual analogue score of the pain on sirolimus with rapid arrest of bleeding after sirolimus initiation and recurrence of symptoms after arrest of sirolimus. The reintroduction of sirolimus at a lower dose subsequently controlled the symptoms.

Clinical case. (A) Extensive bluish lesions on left lower limb; (B) magnetic resonance imaging showing extensive venous malformation in most of the muscles of the thigh (blue arrows); (C) magnetic resonance imaging showing involvement of the perineal area (blue arrows); (D) evolution of symptoms (bleeding and visual analogue score of the pain on sirolimus with rapid arrest of bleeding after sirolimus initiation and recurrence of symptoms after arrest of sirolimus. The reintroduction of sirolimus at a lower dose subsequently controlled the symptoms.

Slow-flow vascular malformations

Venous malformations—PIKopathy

TEK-related VMs

VMs usually appear on the skin or mucosal membranes as soft, bluish, and compressible lesions. Most VMs are sporadic and unifocal. Histologically, VMs are characterized by enlarged, distorted vein-like channels lined with a single layer of ECs and surrounded by disorganized smooth muscle cells (SMCs).

Sixty percent of VMs have GOF pathogenic variants in TEK, the gene encoding TIE2, leading to ligand-independent activation of TIE2.3,4TEK-related VMs are divided into 4 groups5:

1) Common VMs: The vast majority of VMs are sporadic and unifocal, mostly resulting from an L914F pathogenic variant in exon 17 of TEK. Approximately 40% of these VMs occur on the extremities, 40% in the cervicofacial area, and 20% on the trunk. There is no familial history.4

2) Multiple cutaneous and mucosal VMs (VMCMs): VMCMs are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and characterized by the presence of small, multifocal cutaneous and/or oromucosal VMs throughout the body. The R849W pathogenic variant is commonly observed as the inherited mutation, but it also requires a somatic second hit in TEK.6

3) Multifocal VMs (MVMs): Clinically similar to VMCMs, MVMs lack a family history of VMs. These malformations are more frequently located in the cervicofacial area and extremities. They are often intramuscular, well circumscribed and noncompressible on palpation. Patients with an MVM are often mosaic for the first pathogenic variant (commonly R915C) associated with a second-hit pathogenic variant (typically Y897C) in affected areas.4,7

4) Blue rubber bleb nevus (BRBN) syndrome: BRBN is caused by somatic (mosaic) TIE2 pathogenic variants, typically involving a carboxy-terminal double-pathogenic variant T1105N-T1106P, but sometimes others, including Y897F-R915L. BRBN patients are often born with a dominant lesion and develop up to hundreds of widely distributed cutaneous, rubbery, often hyperkeratotic VMs over time, predominantly on palms and soles. Gastrointestinal lesions are pathognomonic.7

PIK3CA-related VMs

Twenty percent of sporadic VMs have a somatic pathogenic variant in PIK3CA, the gene encoding the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K. The hot-spot pathogenic variants are similar to those observed in cancer and include p.Glu542Lys, p.Glu545Lys (helical domain), and p.His1047Leu (kinase domain).8 These pathogenic variants are also found in various PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes (PROS), in which vascular malformations are associated with the hypertrophy of soft and sometimes bony tissues. An example is Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, a combined malformation (capillary-lymphatic-VMs) with overgrowth of the affected limb.9 Other PROS phenotypes, such as congenital lipomatous overgrowth with vascular anomalies, epidermal nevi, and scoliosis (CLOVES) and macrocephaly-capillary malformation, are more frequently associated with non–hot-spot PIK3CA pathogenic variants.10

These pathogenic variants in TEK and PIK3CA result in the excessive activation of AKT. This activation, via FOXO1 inhibition, leads, among others, to inappropriately low platelet-derived growth factor β levels, which subsequently decrease the paracrine EC-SMC interaction.3 Targeted therapies including the inhibition of mTOR (sirolimus) or PIK3CA (alpelisib) have been shown to significantly improve the quality of life of patients.11,12

Glomuvenous malformations

Patients with glomuvenous malformations (GVMs) harbor multifocal bluish-purple, cutaneous vascular lesions, mostly located on the extremities. The lesions are painful and cannot be emptied by compression. There are no intestinal lesions. GVMs are inherited and transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner, with an LOF of Glomulin. The encoded Glomulin, expressed by ECs and SMCs, is thought to be linked to inactivate c-MET; c-MET activation would lead to the phosphorylation of Glomulin and its release from c-MET, allowing the activation of a PI3K cascade by c-MET. Glomulin exerts additional inhibitory effects on transforming growth factor ß (TGF-ß) signaling. The intra- and interpatient variability and the apparition of lesions with time support a second-hit pathogenic variant.13,14

Lymphatic malformations

LM—PIKopathy, rarely Rasopathy

LMs are subdivided into (cystic) LMs and complex lymphatic anomalies (CLAs). Cystic LMs occur as solitary lesions of variable size, classified based on their appearance into macrocystic, microcystic, and mixed cystic LMs. Macrocystic LMs manifest as large, fluid-filled cavities, commonly localized on the neck area. In contrast, microcystic and mixed cystic LMs contain small cysts and diffuse vessel-like lesions. LMs often infiltrate soft tissues and can be found anywhere on the body.

Eighty percent of common LMs have somatic hot-spot pathogenic variants in PIK3CA (E542, E545, and H1047).15 In vivo, early expression of the PIK3CAH1047R pathogenic variant during the embryonic stages is associated with macrocystic LMs, whereas expression in postnatal lymphatic vasculature results in microcystic LMs.16 Similar to VMs, sirolimus or alpelisib could be effective in the management of LMs. Somatic GOF BRAF pathogenic variants have also been described in individuals with non– PIK3CA-mutated LMs.17

CLAs—PIKopathy or Rasopathy

CLAs, by involving multiple localizations, disrupt lymphatic fluid homeostasis, leading to impaired lymph drainage and leakage of lymph into body cavities.18,19 CLAs encompass different entities, based on phenotype and molecular alterations:

1) Generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA): These are characterized by diffuse or multicentric invasive lymphatic lesions in multiple organs, including bones, liver, spleen, lungs, and soft tissues. The bone lesions do not destroy the cortical bone.

2) Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis (KLA): Clinically similar to GLA, this is histologically distinguished by the presence of foci of kaposiform spindle-shaped lymphatic ECs, with relatively frequent thrombocytopenia. Bone lesions do not destroy the cortical bone.

3) Gorham-Stout disease (GSD): Clinically similar to GLA, GSD is marked by progressive bone destruction and resorption.

4) Central conducting lymphatic anomaly (CCLA): CCLA is characterized by dilatation, malformation, and dysfunction of the major conducting abdominal or thoracic lymphatic vessels, including the thoracic duct.

Somatic activating PIK3CA pathogenic variants were detected in up to 55% of patients with GLA.20 Pathogenic variants in the MAPK pathway, including NRAS, KRAS, and ARAF, have been identified in KLA, GSD, and CCLA.21-25 In a few CCLA patients, LOF pathogenic variants in EPHB4, which encodes the ephrin B4 (EPHB4) receptor tyrosine kinase, have been detected. By binding to ephrinB2, EPHB4 enables RASA1 recruitment.26 CCLA may also be associated with distinct phenotypes, based on pathogenic variants in genes such as BRAF, MDFIC PIEZO1, or RASA1.27-30

Capillary malformations

CMs—GNAQopathy

CMs are slow-flow vascular malformations composed of enlarged capillaries and venules with thickened perivascular cell coverage. CMs may present as isolated lesions or be associated with other features, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) or diffuse CM with overgrowth (DCMO). Somatic- activating pathogenic variants in the alpha subunit of guanine nucleotide–binding protein G(q) (GNAQ) are detected in 90% of isolated CMs, in SWS, and in DCMO. GNAQ is a member of a family of heterotrimeric proteins that couple cell-surface receptors to intracellular signaling pathways. This GOF pathogenic variant in GNAQ leads to activation of phospholipase C-β (PLCβ) and ERK.34

Isolated cutaneous CMs, often referred to as port-wine birthmarks, can darken and form nodules over time. In 55% to 70% of cases, soft-tissue overgrowth is observed, especially if the CM is located on the lip or cheek.

SWS is a rare neurocutaneous disorder characterized by congenital capillary-VMs involving the face (facial port-wine birthmark), as well as the ipsilateral leptomeninges and ocular choroid. This results in cerebral (epilepsy, intellectual disability, hemiparesis, visual impairment, and migraines) and ocular (glaucoma) disorders.35

Patients with DCMO tend to have proportionate and milder overgrowth compared to those with PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum.36PIK3CA pathogenic variants have also been described in skin containing CMs and overgrown subcutaneous adipose tissue of patients with DCMO, suggesting DCMO is a part of PROS.36

CMs—PIKopathy or Rasopathy

Alteration in the PI3K-AKT cascade can also be observed in some CM patients. Somatic PIK3R1 and non–hot-spot PIK3CA pathogenic variants have been detected in CMs with dilated veins (PIK3R1-CMDV or PIK3CA-CMDV, respectively).37 Recently, somatic pathogenic variants in AKT3 were detected in 2 young patients with a CM-like phenotype associated with cerebral anomalies and severe epilepsy.38

CM-AVM is a rare disease characterized by the presence of multiple small CMs mostly located on the face and limbs, as well as AVMs present at birth, arising in the skin, muscles, bones, spine, and brain. CM-AVMs are transmitted in an autosomal- dominant manner and belong to the class of Rasopathies. There are 2 types of CM-AVM: CM-AVM1, caused by more than 40 different truncating pathogenic variants in RASA1 that require a second hit on the second allele of RASA1 for a complete loss of RASA1,39 and CM-AVM2, caused by LOF pathogenic variants in EPHB4 that result in constitutive activation of MAPK signaling.40 CM-AVM was also reported to be associated with pericardial/pleural effusions, ascites, and CCLA.41

Fast-flow vascular malformation

Sporadic AVMs

AVMs are fast-flow vascular lesions characterized by abnormal connections between arteries and veins, bypassing the capillary system. Histologically, AVMs feature thick-walled arteries of varying calibers and thick-walled arterialized veins. Present at birth, AVMs are usually isolated and can affect any tissue or organ, progressing over a lifetime. They cause deformation, severe pain, functional impairment, and life-threatening complications including necrosis, heart failure, and cerebral bleeding.

The majority of AVMs occur sporadically and manifest as isolated lesions. Somatic pathogenic variants in MAP2K1, the gene encoding MEK1, were detected in 70% of patients with sporadic extracranial AVMs.42 These pathogenic variants consist of missense or small in-frame deletions affecting the negative regulatory domain of MAP2K1, resulting in increased MEK1 activity. KRAS and BRAF GOF pathogenic variants have also been reported in AVMs, including those in the brain.43 A somatic pathogenic variant in PTEN was reported to be associated with isolated AVM in 1 patient.44

Murine models have shown that KRAS activation in ECs can generate AVMs in multiple soft tissues. Furthermore, treatment with the MEK inhibitor trametinib improved survival and normalized vessel sizes and morphology in these models.45 Based on these observations, trametinib was administered to 10 AVM patients in the phase 2 TRAMAV trial (EudraCT 2019-003573-26), resulting in an 80% clinical benefit rate (Coulie et al, submitted). Moreover, thalidomide, a potent antiangiogenic drug, showed a significant reduction in chronic pain and bleeding and healing of ulcerations.46

Syndromic AVMs

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an inherited autosomal-dominant vascular dysplasia characterized by multiple telangiectasia, found on lips, tongue, buccal and gastrointestinal mucosa, and larger AVMs, commonly in lungs, liver, and brain. The most common clinical manifestations include epistaxis, bleeding, cardiac failure, and pulmonary/portal hypertension. Although the penetrance of the disease increases with age, reaching 90% at 45 years, children can also have severe symptoms with devastating consequences. Ninety-five percent of HHT cases are caused by pathogenic variants in genes in the TGF-β/bone morphogenetic protein signaling pathway, including Endoglin (ENG, mutated in HHT1), activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1, mutated in HHT2), and MADH4 (encoding mothers against decapentaplegic homologue 4 [SMAD4] and mutated in the syndrome of juvenile polyposis and HHT).47

Located on ECs, ALK1 is a type I serine/threonine kinase receptor, and ENG acts as an auxiliary coreceptor that promotes, through the recruitment of type 1 and 2 TGF-β receptors, the phosphorylation of SMAD1, 5, and 8. Once phosphorylated, R-SMADs form heteromeric complexes with SMAD4 and translocate into the nucleus, where they regulate the vascular remodeling and angiogenesis balance. LOFs in these genes lead to destabilization of the vascular structure, as well as in indirect PI3K-AKT activation through decreased PTEN activity. Additional loci were identified on chromosome 5q31.3-32 (HHT3) and 7p14 (HHT4). Missense and stop-gain variants identified in GDF2 (encoding BMP9) have also been reported to be associated with a vascular phenotype similar to HHT.48

PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome

AVMs can also be observed in PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), including Cowden syndrome, Bannayan-Riley- Ruvalcaba syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and autism spectrum disorders associated with macroencephaly. All these diseases share LOF PTEN pathogenic variants that are inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner. Patients with PHTS have macrocephaly, lipomas, and papillomas or trichilemmomas associated with nonpathognomonic cutaneous and deeper soft-tissue vascular lesions, which may contain fast-flow vascular anomalies. Furthermore, as PTEN is an important tumor suppressor gene, patients with PHTS are predisposed to breast, endometrial, renal, and thyroid cancers.49

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient described at the beginning presents an extensive VM associated with important chronic consumptive coagulopathy. As conventional treatment with surgery was unfeasible and sclerotherapies were ineffective, sirolimus was started at 2 mg/d, and doses were adapted in order to reach a serum trough level between 10 and 15 ng/mL. Bleeding stopped after 5 days, and the pain disappeared within the first month. Sirolimus was maintained for 2 years and then stopped. A PIK3CA pathogenic variant was detected on archival tissue sample. While symptoms drastically improved, the radiological size did not change significantly. Three months after sirolimus arrest, the pain and bleeding reappeared progressively. As demonstrated in the VASE study, compared to TIE2-mutated patients, PIK3CA-mutated patients experience a more rapid response but a more rapid symptom resurgence once sirolimus is arrested.11 A reintroduction of sirolimus at a lower dose (1 mg/d) subsequently controlled symptoms; she is still on sirolimus after 10 years. Alpelisib was also tested for 3 months but arrested due to hair loss. While on sirolimus, our patient presented occasional painful episodes with increased D-dimer levels, reflecting acute thrombosis. Intermittent 21-day management with low-molecular-weight heparin, which is commonly used for these patients, resulted in the resolution of these painful symptoms.50

Conclusion

Although sirolimus was initiated in our case without genomic information, as VMs are classically PIKopathies we believe that molecular analysis is important for determining optimal treatment strategies. This case underscores the importance of the accurate classification of vascular malformations to ensure the best multidisciplinary treatment approach. Genomic testing should be recommended for all patients with vascular malformations, allowing further development of targeted therapies. The VASCERN-VASCA genetics task force curated the genes currently known to be associated with vascular anomalies to pinpoint genes that should be included in diagnostic genetic panels.51 In general, somatic testing should be performed for isolated vascular malformations, while germline testing should be proposed to patients with multifocal lesions or a familial history of vascular malformations. Geneticists should be integral members of the multidisciplinary vascular anomaly management teams.

Acknowledgments

The studies on vascular anomaly pathophysiology, genotype-phenotype correlations, preclinical modeling, theragnostics, and clinical trials have been supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique FNRS Grants T.0240.23 and P.C005.22 (to M.V.) and T.00.19.22 and P.C013.20 (to L.M.B) and by the Fund Generet, managed by the King Baudouin Foundation (Grant 2018-J1810250-211305); the Walloon Region, through the FRFS-WELBIO strategic research program (WELBIO-CR-2019C-06); the MSCA-ITN network V.A. Cure No 814316; the 21CVD03 Leducq Foundation Networks of Excellence Program grant “ReVAMP”; the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 874708 (Theralymph; all to M.V.); the Swiss National Science Foundation under the Sinergia project nro CRSII5_193694 (L.B./M.V.); the National Institutes of Health (NIH, United States, RO1HL096384-10); and the FWO scientific research network (W0014200N) on bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vascular biology and disease.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Emmanuel Seront: no competing financial interests to declare.

Angela Queisser: no competing financial interests to declare.

Laurence M. Boon: no competing financial interests to declare.

Miikka Vikkula: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Emmanuel Seront: Nothing to disclose.

Angela Queisser: Nothing to disclose.

Laurence M. Boon: Nothing to disclose.

Miikka Vikkula: Nothing to disclose.