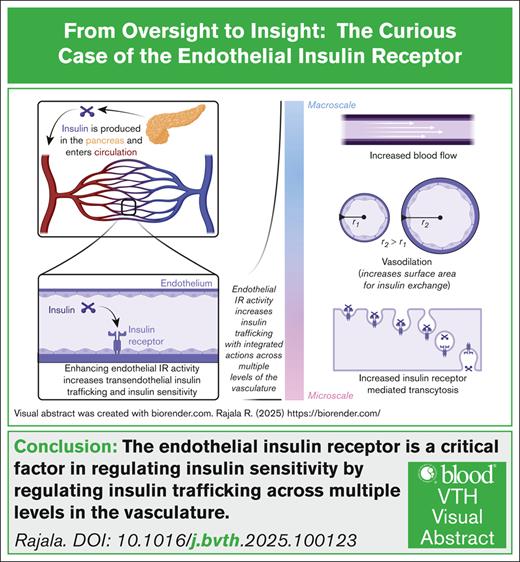

Visual Abstract

Visual abstract was created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/

Visual abstract was created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/

Insulin is produced in the pancreas and regulates blood glucose levels by binding to the insulin receptor (IR) thereby stimulating glucose uptake into cells. Inadequate insulin production or dysregulated IR signaling leads to diabetes. Most research, to date, has focused on enhancing insulin production or correcting impaired IR signaling in tissues of nutrient exchange, for example, muscle or fat. However, the transendothelial trafficking of insulin to target tissues is also crucial in regulating organismal responses to insulin. In fact, this process has been established as the rate-limiting step for glucose disposal. Initially, it was believed that the transendothelial trafficking of insulin was dependent on endothelial IR. Unfortunately, subsequent studies have demonstrated that mice lacking endothelial IR possess minimal changes in insulin sensitivity. These studies have contributed to the widespread belief that endothelial IR does not regulate insulin trafficking and insulin sensitivity. However, recent genetic studies from our laboratory, and others, have shown that enhancing endothelial IR activity improves insulin sensitivity. These studies underscore the crucial role of endothelial IR in regulating insulin trafficking and metabolism. Now that researchers have conclusively demonstrated the presence and function of IR on endothelial cells (ECs) in vivo, it is essential to clarify why this receptor has been so controversial. Additionally, this timely review aims to encourage vascular biology researchers to explore how endothelial IR is regulated and identify new roles for this receptor on ECs.

Introduction

Diabetes affects >537 million adults worldwide and is projected to reach 783 million by 2045.1 The disease is driven by a failure of the hormone insulin’s ability to signal.2 In type 1 diabetes (T1D), the disease is driven by an autoimmune loss of insulin production2 whereas type 2 diabetes (T2D), is driven by metabolic inflammation-mediated insulin resistance.1 Insulin resistance refers to the loss of insulin’s action on the insulin receptor (IR), resulting in elevated blood glucose levels. Approximately 40% of adults in the United States are currently affected by insulin resistance. Both T1D and T2D lead to a decreased ability for glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissues. Understanding the insulin lifecycle is key to designing therapeutics against diabetes.

Insulin is secreted by β cells in the pancreas and released into the portal vein, allowing it to circulate in the bloodstream and reach its target tissues. Insulin then exits the vasculature and binds to parenchymal IRs to signal various physiological actions, notably glucose uptake.3 The primary site of action for insulin is in skeletal muscle, which accounts for up to 85% of glucose uptake.4 Previous studies have demonstrated that the concentrations of insulin in the bloodstream differ from those in the underlying parenchyma, suggesting that trafficking across the vascular endothelium is the rate-limiting step in insulin signaling.5 However, information on how the vasculature affects insulin signaling is limited, which is disappointing given that this pathway may be a promising therapeutic target.

The vascular endothelium comprises the innermost layer of cells in blood vessels and covers a surface area of ∼270 to 720 m2 in humans.6 Until the last 60 years, the endothelium was thought of as simply a sheet of nucleated cellophane, nothing more than an inert barrier to carry blood.7 However, the endothelium is now understood to be a dynamic and vital tissue with crucial functions in every single organ.8-10 In the case of insulin signaling the endothelium plays roles in controlling insulin trafficking through altering blood flow to tissues, changing the surface area of blood vessels via nitric oxide (NO)–mediated vasodilation,11,12 and regulating receptor-mediated insulin transcytosis.3,5,13 All of these effects are regulated by endothelial IR signaling. However, at the same time, in vivo genetic studies that removed IR from endothelial cells (ECs) suggested limited roles for endothelial IRs in affecting insulin sensitivity.12 This review addresses this controversy and provides a vision of how this debated receptor functions in the endothelium based on recent breakthroughs in endothelial IR research.14,15

A brief history of endothelial IR and its controversy

The theory that EC IR regulates the transendothelial trafficking of insulin is controversial.5 As early as 1978, IRs were detected on cultured ECs.16 Within the next decade, insulin was shown to be rapidly internalized and trafficked through ECs with little to no degradation.17,18 By the end of the 1980s, Yang et al carefully measured insulin concentrations in plasma and lymph in dogs after insulin infusions. Lymph fluid was used because its insulin levels are arguably equivalent to those of interstitial fluid. These studies revealed that the concentrations of plasma insulin were consistently higher than those of lymph after infusions,19,20 suggesting the endothelium regulates insulin trafficking. Around the same time, studies by Bar et al demonstrated that IRs on small capillaries in rats were critical for trafficking insulin to parenchymal tissues.21 By the end of the 1990s, it was shown that insulin is trafficked by the ECs through distinct plasmalemmal vesicles.22 Taken together, these studies suggested that transendothelial insulin trafficking was the rate-limiting step for glucose disposal and was dependent on EC IR-mediated vesicular transport.

However, this theory quickly came under fire. By the early 2000s, with the advent of Cre-lox technology and EC-specific Cre drivers, researchers were able to generate mice with the EC-specific deletion of IR (IrECko).

Interestingly, IrECko mice demonstrated limited changes in insulin sensitivity or glucose homeostasis.12 However, later studies did show delays in insulin signaling in certain tissues (ie, skeletal muscle, brown fat, and parts of the brain).23 These findings suggested a lesser role for endothelial IR in mediating insulin sensitivity. Additionally, recent single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) studies by Kalucka et al identified limited IR expression in skeletal muscle capillaries,24,25 which further argues for a lesser role for EC IR in regulating insulin trafficking. This has resulted in the common perception that endothelial IR does not play a role in transendothelial insulin trafficking or influence insulin sensitivity, until now.

Genetic models resulting in endothelial IR gain of function reveal it to modulate insulin sensitivity

Although evidence regarding the impact of endothelial IR on insulin sensitivity is mixed, a growing body of research demonstrates that heightened endothelial IR activity enhances insulin sensitivity. In 2020, a study by Sun et al found that mice with endothelial-specific overexpression of transcription factor EB (Figure 1) exhibited increased expression of the IR signaling adaptor proteins IR substrate 1 and 2 (IRS1 and IRS2). As a result, these mice exhibited heightened insulin sensitivity and improved systemic glucose tolerance while on a high-fat diet, a model of T2D. These studies indicated that although the loss of endothelial IR had minimal effects on insulin sensitivity, enhancing endothelial IR signaling could still improve insulin sensitivity. However, it was not until 2025 that researchers were able to establish that directly increasing the activity of the endothelial IR itself was sufficient to improve insulin sensitivity in vivo.

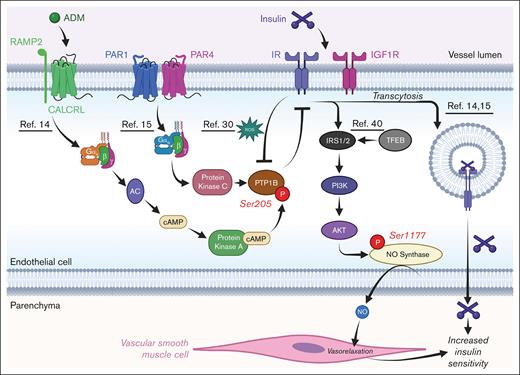

Schematic of how IR signaling in ECs is regulated. Depiction of how various receptors cross talk with IRs; relevant references are underlined. AKT, protein kinase B; cAMP, cyclic AMP; PAR, protease-activated receptor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RAMP, receptor activity-modifying protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Schematic of how IR signaling in ECs is regulated. Depiction of how various receptors cross talk with IRs; relevant references are underlined. AKT, protein kinase B; cAMP, cyclic AMP; PAR, protease-activated receptor; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RAMP, receptor activity-modifying protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

These studies were conducted in 2 laboratories that focused on cross talk between IRs and G protein–coupled receptors in ECs. The first study by Cho et al found that adrenomedullin, a peptide hormone with increased levels in patients with T2D,26 activates the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CALCRL) in ECs. Activation of CALCRL triggers Gαs signaling, increasing adenylate cyclase activity, cyclic AMP levels, and protein kinase A (PKA) activity in the cell. This rise in PKA activity leads to phosphorylation of Ser205 of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), which increases the phosphatase activity of the enzyme.14 PTP1B is a negative regulator of insulin signaling,27 whose inhibition results in increased IR activity and enhanced insulin uptake and transcytosis in EC in vitro.11,14,15,28-30 Thus, activation of endothelial CALCRL was found to reduce IR activity in ECs in a PTP1B-dependent manner14 (Figure 1). Concordantly, mice with EC-specific deletion of CALCRL (CalcrlECko) have increased endothelial IR activity and improved systemic glucose tolerance during challenge with a high-fat diet. This suggests that enhancing endothelial IR activity improves insulin sensitivity.

The second study by Rajala and Griffin found that loss of protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 (PAR1/4) in ECs, which are activated by thrombin and other proteases,31,32 also reduced PTP1B activity in ECs15 (Figure 1). In this case, loss of PAR1/4 resulted in reduced Gαq signaling, which, in turn, reduced protein kinase C (PKC) activity in the cell15 (Figure 1). This loss of PKC likely resulted in reduced Ser378 phosphorylation of PTP1B,33 a potential activating mark for the enzyme.14 Mice with EC-specific deletions of PAR1/4 (Par1/4ECko) demonstrated increased insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance and were also protected against a streptozotocin model of T1D. Furthermore, this protection from streptozotocin was attenuated in Par1/4ECko mice with genetic reductions in endothelial IR (Insr). This further suggests that rises in insulin sensitivity in Par1/4ECko mice were dependent on enhanced endothelial IR activity. In either case, it appears that reducing the signaling of certain heterotrimeric G-protein subunits (Gαs or Gαq) increases IR activity in ECs in a PKA- or PKC-dependent manner, thereby promoting insulin sensitivity.

Therefore, the endothelial IR appears crucial for regulating insulin sensitivity in vivo. However, questions remain over why the early studies on IrECko mice failed to display reduced insulin sensitivity12 and why the expression of Insr appears to be low in scRNAseq data sets of muscle ECs.24,25 In the case of the former, it is possible that insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF-1R/Igf1r), which is also present in the vascular endothelium, can still bind insulin (albeit with 100-fold less affinity).34,35 In fact, it has been shown that IGF-1R is severalfold more abundant than IR in ECs,36 which may compensate for its lower binding affinity to insulin. As a result, it is possible that IGF-1R can still bind and traffic insulin even when IR is absent in ECs.35,37 To wit, it has been shown that the use of an IGF-1R–neutralizing antibody in vitro reduced transendothelial insulin trafficking, similar to the use of an IR-neutralizing antibody.38 Therefore, to reduce insulin sensitivity by modifying EC insulin trafficking, one may need to lose both IR and IGF-1R. Concordantly, mice with EC-specific IRS2 deletion (Irs2ECko) showed more substantial reductions in insulin sensitivity than IrECko mice.12,23,39,40 However, because IRS2 is recruited to both activated IR and IGF-1R in response to ligand stimulation of each receptor,41 this phenotype may be akin to dual loss of IR and IGF-1R in ECs.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations when this theory is extended in vivo. In the case of NO, it has been shown that loss of IGF-1R increases NO42 and the overexpression of IGF-1R in ECs, resulting in reduced NO bioavailability.43 This is the opposite of what happens with activation and loss of IR,42 because IR activity positively correlates with NO production.14 Therefore, although each receptor’s physical presence may redundantly mediate insulin’s transendothelial trafficking, they might also exhibit nonredundant antagonistic signaling in ECs. This is somewhat consistent with findings from Rajala and Griffin, who demonstrated that their Par1/4ECko mice with heightened insulin sensitivity possessed only increased activity of IR but not IGF-1R.15 Thus, it appears that endothelial enhancements of insulin sensitivity are mediated by enhancing IR-specific signaling.

Nonetheless, this interpretation of IR/IGF-1R redundancy on ECs is reasonable. Given that transendothelial insulin trafficking is rate-limiting for glucose disposal, it would be expected that ECs would use redundant mechanisms. However, future studies generating endothelial IR/IGF-1R double-knockout mice are needed to conclusively demonstrate whether IGF-1R acts redundantly to IR in the endothelium to regulate insulin sensitivity. These studies may need to be done in an inducible manner, because it has been previously shown that IR/IGF-1R double-knockout mice display perinatal lethality due to cardiovascular defects.44 Moreover, these studies could take advantage of cell-specific degron systems45 that would allow for rapid and reversible removal of proteins from ECs in vivo. This result is achieved by using synthetic ligands to mobilize target proteins to E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes, enabling rapid degradation of the target. This approach enables the swift removal of both receptors on ECs, which may be advantageous for discerning long-term effects mediated by insulin signaling (vascular tone, capillary number) vs short-term effects mediated by insulin trafficking (transcytosis).

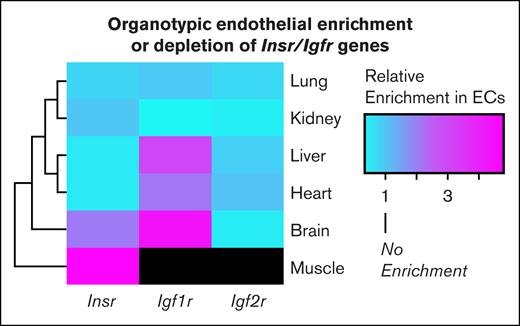

Regarding the second question about why Insr expression appears low in scRNAseq data sets of muscle ECs, as discussed in a recent review by Williams and Wasserman,25 this low expression might be an inherent artifact of the scRNAseq method. The technique of scRNAseq requires the dissociation of cells into a single-cell suspension. However, cells tightly embedded in tissue are often missed during sequencing. Given that ECs are tightly embedded in muscle fibers, it is possible and likely that scRNAseq misses sequencing of ECs in muscle. Furthermore, ECs and other cells have been shown to undergo phenotypic drift during tissue digestion and trituration during scRNAseq processing.46,47 For these reasons, many researchers are embracing the technique of translating ribosome affinity purification, which isolates ribosome-bound mRNAs from specific cell types by using a cell-type–specific promoter to label ribosomal proteins with an affinity tag.46,48-50 This technique allows researchers to profile actively translated transcripts in vivo while avoiding issues of phenotypic drift. Using this approach, Rajala and Griffin recently demonstrated that the muscle endothelium has enriched expression of Insr when compared with the muscle parenchyma.15 I extended these findings in this review by surveying an atlas of endothelial translating ribosome affinity purification data from all organs.15,46 I found that the enrichment of Insr was unique to the endothelium of the muscle but not to the brain, liver, lung, heart, and kidney (Figure 2). Therefore, with the advent of these studies, there appears to be sufficient evidence that endothelial IR is a meaningful receptor on ECs whose activation improves insulin sensitivity. However, the question remains whether EC IRs promote insulin sensitivity through receptor-mediated transcytosis or alternative mechanisms.

TRAP reveals organotypic enrichment and depletion of endothelial IR. Heat map of endothelial enrichment scores of select IR family genes across different organs. The figure was generated using publicly available translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) data from Cleuren et al46 and Rajala and Griffin.15 The enrichment score is defined as . Black shading refers to enrichment scores, which were not publicly available. Igf2r, insulin growth factor receptor 2.

TRAP reveals organotypic enrichment and depletion of endothelial IR. Heat map of endothelial enrichment scores of select IR family genes across different organs. The figure was generated using publicly available translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) data from Cleuren et al46 and Rajala and Griffin.15 The enrichment score is defined as . Black shading refers to enrichment scores, which were not publicly available. Igf2r, insulin growth factor receptor 2.

To transcytose or not to transcytose?

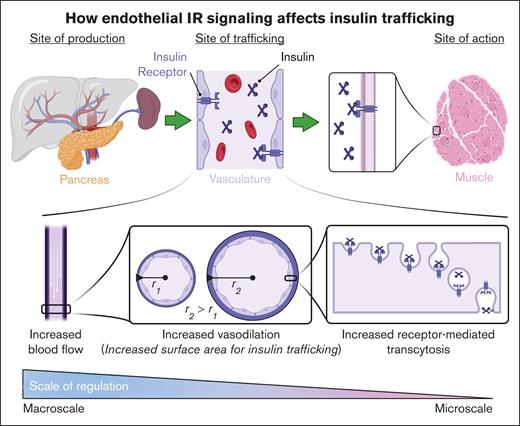

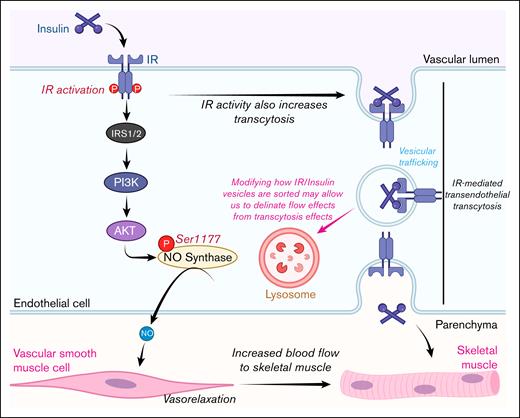

The role of IR-mediated transendothelial insulin transcytosis has been the most challenging aspect to clarify when the mechanisms of insulin delivery in vivo are studied. Thus far, it has been impossible to separate the effects that endothelial IR signaling has on insulin transcytosis from its impact on blood flow. However, given that the trafficking of insulin from microcirculation to the interstitium is the rate-limiting factor for glucose uptake, this type of multilevel regulation is to be expected. This regulation would enable insulin to promote its own trafficking at multiple levels of the vascular bed, ranging from the macroscale to the microscale (Figure 3).

Schematic of how endothelial IR signaling affects insulin trafficking. The upper panel illustrates the lifecycle of insulin, from its production site to its site of action. The lower panel depicts the multiple levels of regulation (macro and micro) that the endothelium uses to regulate insulin trafficking. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Schematic of how endothelial IR signaling affects insulin trafficking. The upper panel illustrates the lifecycle of insulin, from its production site to its site of action. The lower panel depicts the multiple levels of regulation (macro and micro) that the endothelium uses to regulate insulin trafficking. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

On the macroscale, insulin increases blood flow by increasing heart rate51 and the vasodilation of blood vessels,14,52,53 thereby increasing the surface area for insulin exchange and promoting insulin sensitivity. On the microscale, it is known that enhancing endothelial IR activity improves insulin transcytosis, as demonstrated in recent studies by Rajala and Griffin15 and Cho et al.14 However, it remains unknown how exactly increasing IR activity enhances transcytosis. Studies by Azizi et al have shown that in adipose-derived microvascular ECs, transcytosis involves vesicle internalization, dependent on dynamin and clathrin, but not caveolin or cholesterol.54 However, it does appear that endothelia from large vessels11,38,55 and lung microvascular ECs56 use caveolin for insulin uptake. This suggests that organotypic and zonation-specific heterogeneity exists with insulin uptake. However, it is currently unknown whether changes in IR activity influence the activity of dynamin, clathrin, and caveolin in the ECs, warranting future investigation.

Another possibility is that increased basal IR phosphorylation/activity may enhance internalization dynamics. It has been shown that spliceforms of IR associated with high basal activity also have more rapid internalization and a higher binding affinity to insulin.15,57,58 Therefore, it is possible that phosphorylating the C-terminal loops to activate IR before insulin binding may enhance receptor internalization and promote insulin binding; however, this also remains to be studied.

Nonetheless, these studies are limited because they still do not prove that receptor-mediated transcytosis occurs in vivo. However, determining the mechanism of insulin trafficking in vitro may enable the design of genetic experiments to ascertain whether IR-mediated transcytosis occurs in vivo.

How can one determine that receptor-mediated transendothelial transcytosis occurs in vivo?

Drawing insights from the fact that recent genetic models clarified the role of endothelial IR in regulating insulin sensitivity, it appears probable that a similar approach will ultimately resolve this debate. The issue at hand is distinguishing effects driven by endothelial-IR–mediated changes in blood flow from effects driven by endothelial-IR–mediated transcytosis. I postulate that the solution exists by better identifying how IR/insulin vesicles avoid degradation in ECs.22,54 By identifying the protein machinery that mediates the intercellular trafficking of these vesicles, for example, lysosomal sorting nexins,59 researchers may be able to distinguish effects mediated by IR signaling from IR-mediated transcytosis (Figure 4). For example, if it were known that specific epitopes of insulin-bound IR interacting with a particular sorting protein hindered its localization to lysosomes, then modifying these epitopes in vivo in ECs could lead to the lysosomal degradation of insulin in ECs. This would block the effects of IR-dependent transcytosis while still maintaining IR signaling. Notably, conducting these experiments may need to be performed in Igf1rECko mice due to receptor redundancy, as previously discussed.

Schematic of how targeting intercellular sorting could validate the endothelial IR transcytosis hypothesis. AKT, protein kinase B; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Schematic of how targeting intercellular sorting could validate the endothelial IR transcytosis hypothesis. AKT, protein kinase B; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Why might insulin be routed by IR-mediated transendothelial transcytosis: endocrine vs paracrine control of glucose disposal?

Although the concept of IR-mediated transendothelial trafficking is controversial, this form of trafficking offers key benefits. As with all endocrine hormones, insulin production in the pancreas occurs distanl from the site of action (skeletal muscle/fat; Figure 3). The primary role of insulin is to promote the movement of glucose transporters such as glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) to the cell membrane, enabling glucose uptake into myocytes and adipocytes.60 However, because GLUT4 is a passive transporter, a strong concentration gradient is required to ensure efficient and rapid glucose uptake. This concentration gradient forms due to the delay between the rise in glucose levels and the delivery of insulin to the interstitium. This delay is partly due to a lag in insulin production after a rise in blood glucose and processing and clearance of insulin by the liver61,62 before it reaches peripheral circulation. However, another considerable portion of the delay comes from the time it takes for insulin to move from the bloodstream into the parenchymal tissue. By having insulin’s transendothelial trafficking be a rate-limiting step in glucose disposal, the body ensures a strong concentration gradient for glucose by the time insulin reaches its target.

Another noteworthy benefit of having receptor-dependent transendothelial trafficking of insulin is the ability to abrogate control from the site of production to be closer to the site of action. Without this form of regulation, the action of insulin is only controlled in an endocrine manner by oscillating the levels of insulin production and secretion. However, by making transendothelial insulin trafficking the rate-limiting step in insulin action, the entire vasculature effectively serves as a reservoir from which insulin can be drawn into surrounding tissues. This setup may allow individual tissues to control insulin delivery by locally modulating EC IR activity, as recent studies suggest.14,15 Because most cells lie within 100 to 200 μm of a capillary,63 this mechanism would allow for the decentralized regulation of glucose uptake throughout the vascular network. Although this idea is compelling, extensive experimentation is required to confirm that such a regulation exists. Future studies should investigate whether parenchymal cells secrete factors in response to insulin saturation to limit transendothelial insulin transcytosis. Additionally, if transendothelial insulin transcytosis can be limited, is this regulation dependent on endothelial IR? Answering these questions would allow us to better understand how the endothelium controls insulin trafficking.

What is the relationship between endothelial insulin transcytosis and diabetes?

Does diabetes alter endothelial IR-mediated transendothelial trafficking?

Diabetes reduces endothelial IR expression

Studies by Rajala and Griffin showed that the muscle endothelium selectively reduces expression of Insr in T1D mice induced with streptozotocin.15 This suggests that IR in muscle ECs is uniquely sensitive to changes induced by diabetes. Because endothelial IR regulates transendothelial trafficking of insulin, this reduction in endothelial IR could reduce the amount of insulin trafficked to the parenchyma, further exacerbating the diabetic phenotype.

Diabetes increases PTP1B activity and levels

Similarly, studies by Cho et al have shown that T2D pathology leads to increased PTP1B activity in ECs.14 It has also been shown that PTP1B levels increase with diabetic inflammation, in a tumor necrosis factor α–dependent manner,64 although this has yet to be shown in ECs. In both cases, increasing PTP1B functionality in ECs would reduce transendothelial trafficking of insulin and insulin sensitivity in mice. Additionally, it has been shown that the fatty acid palmitate, which is often used to model inflammatory responses triggered by diabetes,65 also reduces endothelial insulin transcytosis in vitro.66 Palmitate has been shown to increase PTP1B expression in cells.67,68 However, whether PTP1B is responsible for reductions in palmitate-mediated endothelial insulin transcytosis remains unknown. Regardless of the mode of PTP1B induction, this relationship between inflammation, PTP1B activity, and endothelial IR trafficking may serve a critical role in regulating the size of adipose tissue. Insulin is a potent adipogenic hormone that promotes the uptake of circulating fatty acids and increases triglyceride synthesis.69 However, in obesity, hypertrophic adipose tissue releases cytokines and promotes inflammation,70 leading to increased PTP1B activity in nearby ECs. This relationship may serve as a form of negative regulation, in which the increased endothelial PTP1B activity aims to reduce further insulin trafficking to the inflamed, hypertrophic adipose tissue, thereby potentially helping to limit further growth.

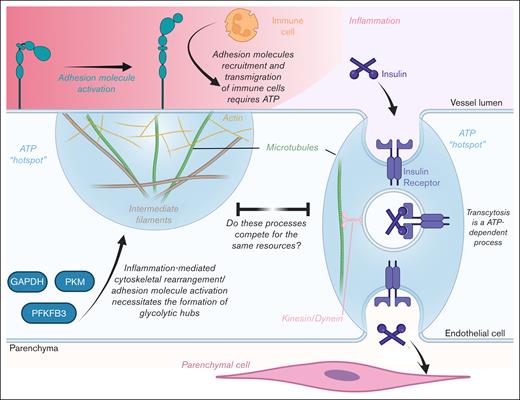

Does diabetic inflammation reduce transendothelial insulin trafficking by competing for ATP hot spots?

Studies have shown that ECs generate “glycolytic hubs” during angiogenesis (Figure 5).71,72 These hubs are microdomains on the plasma membrane in which glycolytic enzymes are recruited via binding to filamentous actin, thereby generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hot spots. During tip cell formation, the actin cytoskeleton is drastically remodeled to form filopodia and lamellipodia. However, these structures require the hydrolysis of large amounts of ATP, which necessitates the generation of these hot spots.

Schematic of how inflammation may potentially reduce endothelial insulin transcytosis by competing for ATP hot spots. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PFKFB3, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3; PKM, pyruvate kinase M1/2. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Schematic of how inflammation may potentially reduce endothelial insulin transcytosis by competing for ATP hot spots. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PFKFB3, 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3; PKM, pyruvate kinase M1/2. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Interestingly, similar remodeling of the cytoskeleton occurs during endothelial inflammation when actin is redistributed from a cortical ring to stress fibers, thereby altering the shape of the cell.73,74 Additionally, the cytoskeleton also undergoes rearrangement to regulate vascular permeability and immune-cell transendothelial migration.73,75,76 Moreover, inflammation stimulates the expression and activation of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecule, and selectins). These molecules bind corresponding ligands on the surface of immune cells, thereby facilitating immune cell adhesion and transmigration.66,77 All these processes require substantial ATP in a localized manner.75,78 Thus, there is evidence that inflammation also generates and consumes ATP hot spots required for cytoskeleton remodeling and transendothelial migration of immune cells. Given this, a crucial question arises: how do these processes affect the transendothelial trafficking of insulin during diabetic inflammation?

It is well established that endothelial insulin transcytosis uses vesicles.54 In neurons, it has been shown that vesicular formation, trafficking, and release consume substantial amounts of ATP.79-81 In fact, synaptic boutons, in which synaptic vesicles are constantly recycled, depend on their own mitochondria to meet these considerable energy demands.80,82 In contrast, ECs, due to their strong reliance on glycolysis, will likely use glycolytic hubs to supply the energy needed for the vesicular trafficking of insulin. However, given that glycolytic machinery is finite in an EC, one must ask whether insulin trafficking is restricted by the additional demands for cytoskeletal rearrangement placed on ECs during inflammation. If this is true, then perhaps inflammation-mediated rises in PTP1B levels and activity14,67,68 are simply protective measures by ECs to limit noninflammatory cytoskeletal rearrangement and conserve ATP during inflammation. Future studies could test this theory by examining whether insulin transcytosis creates ATP hot spots and whether these hot spots compete with those formed by inflammation.

Quo vadis, where do we go from here? Novel areas of inquiry

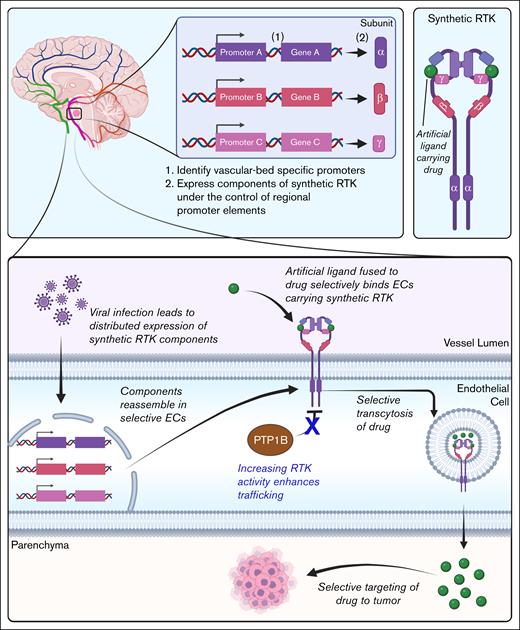

Can endothelial receptor transcytosis serve as a therapeutic target?

Although this review has primarily examined how endothelial IR-mediated insulin trafficking influences disease and vice versa, these insights into insulin trafficking have broader relevance. Receptor-mediated transcytosis in ECs could be a model for developing novel drug delivery strategies. Below, I present 1 example to illustrate how a deeper understanding of insulin transcytosis could enable more precise therapeutic targeting (Figure 6). Occasionally, neurological tumors develop in inoperable locations. Additionally, the blood-brain barrier often blocks many chemotherapy drugs from reaching brain tumors.13,83 I propose that by designing drugs that exploit receptor-mediated transcytosis, it may be possible to bypass the blood-brain barrier and selectively deliver therapeutics to the brain (Figure 6). If one can generate a synthetic receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK),84,85 which mimics IR but does not bind insulin, this artificial/synthetic RTK can be paired with an engineered ligand covalently fused to a chemotherapeutic.86 Because endothelial IR traffics insulin without degradation, this synthetic RTK could deliver chemotherapeutics to otherwise inaccessible tumors.

Schematic of a potential chemotherapeutic that takes advantage of endothelial receptor-mediated transcytosis. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Schematic of a potential chemotherapeutic that takes advantage of endothelial receptor-mediated transcytosis. Figure created with biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

Furthermore, by leveraging the concept of intraorgan vascular zonation, wherein different vascular regions within the same organ display unique transcriptomic profiles, one could identify a series of promoters specifically expressed in the vasculature surrounding the tumor. Using viral gene therapy, one could then drive the distributed expression of different components of the synthetic RTK under the control of these promoters.87,88 This approach could enhance the precision of targeted drug delivery, because the full synthetic RTK assembles only in the ECs adjacent to the tumor. As a result, the drug-carrying ligand is specifically targeted to the tumor. Lastly, the use of IR transcytosis agonists such as PTP1B inhibitors11,15,28 could also allow for enhanced drug delivery to the target. Future investigations could determine whether approaches such as these make for viable therapies.

Does endothelial IR mediate prosurvival signaling in ECs?

Studies show that IR signaling in ECs can regulate metabolism by increasing insulin sensitivity. However, little is known about the nonmetabolic roles that IR can play in ECs. In photoreceptors (PRs), IR and IGF-1R promote cell survival.89-91 Likewise, in ECs, IR kinase activity is selectively upregulated in response to activated protein C,15,92 a factor known for its protective effects on ECs,93 suggesting that IR may also support EC survival.15

Interestingly, elevated IR signaling often promotes cancer in many cells.94 This is partly because IR signaling boosts cellular anabolism,95 which is essential for the uncontrolled growth and proliferation observed in tumorigenesis. However, this phenotype is not seen in ECs and PRs. This resistance to IR-mediated cancer may be due to the unique metabolism of these cells. ECs and PRs primarily rely on glycolysis for energy production, even when oxygen is present, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect.96,97 Cancer cells also display the Warburg effect. However, unlike cancer cells, PRs and ECs can productively use their heightened cellular anabolism. PRs use their heightened metabolism to replenish their outer segment disc membranes,98 whereas ECs use their heightened metabolism for the biosynthesis of lipids and to switch from quiescence to their activated state rapidly.99 If this theory holds, then endothelial IR may be a target for diseases associated with EC loss, for example, ischemia reperfusion.100 Future studies can establish additional nonmetabolic effects that IR can mediate in ECs.

Conclusion

In summary, although the role of endothelial IR in regulating transendothelial insulin trafficking and insulin sensitivity has been controversial, recent studies suggest it does indeed play critical roles in these processes. However, key questions remain, particularly those regarding whether this receptor controls endothelial transcytosis and the cellular pathways that mediate these physiologically relevant functions in insulin resistance and diabetes, necessitating future studies in these areas.

Acknowledgments

The author regrets that some colleagues’ works could not be referenced or discussed due to space limitations. The author thanks Charmain Fernando Johnson (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation [OMRF]) for her help in proofreading this article and Courtney Griffin (OMRF) for her steadfast support during the preparation of this review. Figures 1 and 3-6 and the visual abstract were made using biorender.com. Rajala R. (2025) https://biorender.com/.

This work was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the American Heart Association (23PRE1014240) and OMRF (R.R.).

Authorship

Contribution: R.R. conceptualized the study, performed formal analysis, acquired funding, performed the investigation and visualization, designed methodology, wrote the original draft, and reviewed and edited the final draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.R. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rahul Rajala, University of Oklahoma College of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Campus, 941 Stanton L Young Blvd, BSEB 258, Oklahoma City, OK 73104-5019; email: rahul-rajala@ou.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available from the corresponding author, Rahul Rajala (rahul-rajala@ou.edu), on reasonable request.