Key Points

A genetic RiboTag-based murine model allows identification of reticulated platelets in mice without RNA-binding dyes.

Reticulated platelets increase after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury with enhanced activation and distinct transcriptional profile.

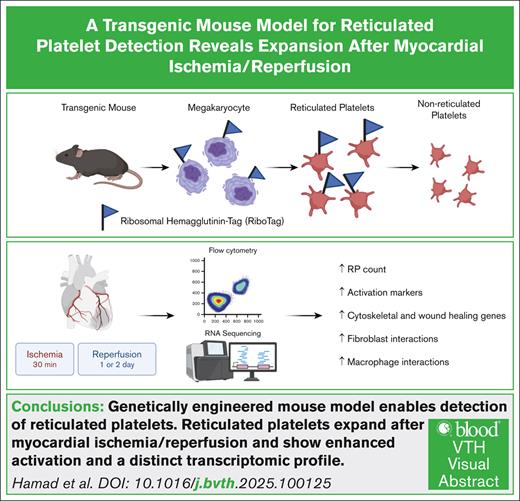

Visual Abstract

Reticulated platelets are newly formed, RNA-rich platelets with heightened reactivity. Although elevated levels are observed after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, their functional contributions to postischemic pathology remains poorly defined. We aimed to determine whether reticulated platelets actively contribute to inflammation and repair following myocardial ischemia and reperfusion, rather than serving solely as biomarkers of platelet turnover. We generated Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice, in which hemagglutinin-tagged ribosomal proteins are selectively expressed in megakaryocytes and platelets. Using hemagglutinin-based flow cytometry, we identified reticulated platelets without relying on nucleic acid dyes. Surface marker expression and agonist responsiveness were evaluated ex vivo. Bulk RNA sequencing was performed on sorted reticulated and non-reticulated platelets 48 hours after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Hemagglutinin-based detection revealed a time-dependent increase in circulating reticulated platelets after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, confirmed by conventional dye-based methods. These platelets exhibited higher baseline expression of glycoprotein Ibα and greater agonist-induced activation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and P-selectin. Transcriptomic profiling demonstrated enrichment of genes associated with platelet activation, cytoskeletal reorganization, and wound healing. Ligand-receptor analysis suggested interactions between reticulated platelets and cardiac endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages. In conclusion, reticulated platelets constitute a transcriptionally distinct, hyperreactive platelet subset that may modulate post–ischemia/reperfusion inflammation and tissue remodeling. This genetic model provides a platform for mechanistic studies and may inform therapeutic strategies targeting platelet-mediated responses in cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the United States.1 Although prompt reperfusion therapies have improved outcomes, many patients experience residual myocardial damage, adverse remodeling, and recurrent events.2-5 Platelets are key players in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, mediating thrombosis, inflammation, and tissue remodeling.6-11 Reticulated platelets (RP) are newly generated, RNA-rich, immature platelets with active translational machinery and heightened reactivity.12,13 RP contain more α- and dense granules and show higher expression of P-selectin and glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa, which enhances adhesion and thrombus formation.14-16 Elevated levels of circulating RP have been observed in patients after myocardial I/R injury and correlate with poor response to antiplatelet therapies.17,18 However, although RP are often used as biomarkers of platelet turnover, their potential to actively shape post–myocardial I/R pathology remains poorly understood. Recent studies have highlighted that RP exhibit distinct transcriptional and phenotypic profiles, characterized by elevated surface expression of GPVI and CD63 and increased fibrinogen binding, linking them to thromboinflammatory and reparative responses following vascular injury.19-21 Current detection methods for RP rely on RNA-binding dyes, such as SYTO13 or thiazole orange (TO), which stain nucleic acids to distinguish young platelets.14-16,22 Although widely used, these approaches have important limitations, as they can stain DNA and nonspecifically label other cell types or microparticles.14,22 Furthermore, because RP lack unique surface markers to distinguish them from mature platelets, their identification within complex tissues is not feasible using RNA-binding dye–based methods, as the signal from surrounding nucleated cells can easily obscure the relatively weak signal from RP.16 Moreover, most studies have quantified RP percentages without directly probing their activation state or molecular identity.

To overcome these limitations, we used a genetically engineered mouse model enabling cell type–specific tagging of ribosomes. In this RiboTag system, the ribosomal protein gene Rpl22 carries a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged exon activated by Cre recombinase.23 As RP retain ribosomes and active translation, the HA tag serves as a specific marker for their identification, whereas aging platelets lose the tag as ribosomes degrade.13 To achieve megakaryocyte-specific expression, we generated Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice by crossing mice in which Cre recombinase is driven by the platelet factor 4 (Pf4) promoter,24 resulting in HA-tagged ribosomes in newly formed platelets.

The purpose of our study was to establish, to our knowledge, the first genetically engineered murine model for RP detection and to investigate their role in post–myocardial I/R repair and remodeling.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

A comprehensive list of all materials and reagents used in this study can be found in supplemental Table 1. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the German Animal Protection Law and approved by the state government authorities in Baden-Württemberg, Germany (approval no. 35-9185.81/G-20/60).

Generation of Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice

To generate a mouse model for RP detection, male hemizygous Pf4-Cre mice [C57BL/6-Tg(Pf4-icre)Q3Rsko/J; stock no. 008535, The Jackson Laboratory, Ellsworth, ME]24 were crossed with female homozygous RiboTag mice (B6N.129-Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J; stock no. 011029, The Jackson Laboratory).23 The RiboTag allele carries a floxed Rpl22 exon with a C-terminal HA tag, consisting of 3 HA epitopes inserted immediately upstream of the stop codon. Because the Pf4-Cre mice express codon-improved Cre recombinase under the control of the Pf4 promoter is active in megakaryocytes. In the resulting Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice, Cre-mediated recombination occurs specifically in megakaryocytes, enabling the expression of HA-tagged Rpl22 in this lineage.

Genotyping of Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice

Genomic DNA was isolated using the Extract-N-Amp Tissue Kit (Sigma), and polymerase chain reactions (PCR) was performed using the KAPA2G Fast HotStart PCR Kit (Merck) according to the manufacturer instructions. Primer sequences, expected amplicon sizes, and thermal cycling conditions for both Pf4-Cre and RiboTag alleles are provided in supplemental Table 2. Representative genotyping results are shown in supplemental Figure 1. Only male Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice (aged 10-14 weeks) carrying both Pf4-Cre and homozygous RiboTag alleles were included in experiments.

Murine model of myocardial I/R injury

Myocardial I/R injury was induced as previously described.8 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (4.8 mg/kg), with buprenorphine (125 μg/kg) for analgesia. Warmed saline with 5% glucose (500 μL) was given to prevent dehydration. Mice were intubated, mechanically ventilated (peak pressure level 10 cm H2O; 110 breaths per minute, inspiration:expiration [I:E] = 1:1.5), and maintained at 37°C. Anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane; vital signs (SpO2, heart rate, and respiratory rate) were monitored throughout the surgery. A left thoracotomy was performed, and the left anterior descending (LAD) artery was transiently occluded using an 8-0 nylon suture and a 0.61-mm polyethylene tube for 30 minutes, ischemia was confirmed visually by myocardial blanching. Reperfusion was initiated by removing the tube. The chest was closed, mouse extubated, and postoperative buprenorphine injection administered (every 8 hours). Sham controls underwent identical procedures without arterial occlusion.

Blood collection

Mice were euthanized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg), and blood was collected by cardiac puncture into a 24-gauge heparin-coated syringes. Samples were anticoagulated with enoxaparin (1.5 μg/mL) and diluted 1:10 with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline containing calcium and magnesium (DPBS+/+). All samples were processed within 30 minutes after blood collection.

Flow cytometry staining protocols

Detection of RP using RiboTag

Diluted blood samples were incubated with a thrombin receptor agonist (protease-activated receptor 4 [PAR-4] peptide, 400 μM) or DPBS+/+ (15 minutes, room temperature [RT]). Following this, samples were stained with mouse anti-mouse/rat CD62P-PE/Cy7 (1:100) and rat anti-mouse CD41/61-PE (JON/A, 1:25) or corresponding isotype controls (15 minutes, RT, in the dark). Samples were then mixed and incubated with prewarmed (37°C) Phosflow lyse/fix buffer (BD Biosciences; 15 minutes, RT, in the dark), followed by centrifugation at 700g (5 minutes, RT). Pellets were resuspended in DPBS+/+ and stained with rat anti-mouse-CD42b-DyLight 649 (1:50, 15 minutes, RT, in the dark). After washing with DPBS+/+ (700g, 5 minutes, RT), samples were permeabilized using 0.1% TritonX-100 (10 minutes, RT). Following permeabilization, cells were washed in DPBS+/+ supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (700g, 5 minutes, RT, repeated 3 times) and stained with mouse anti-HA.11-Brilliant Violet 421 or isotype control (30 minutes, RT, in the dark). Samples were washed with DPBS+/+ supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (700g, 5 min, RT), resuspended in DPBS+/+ and analyzed using flow cytometry.

RP detection using SYTO 13 or TO

Staining of RP with SYTO 13 (green in color) and TO was performed as previously described.16 Diluted blood samples were incubated with prewarmed (37°C) Phosflow lyse/fix buffer (15 minutes, RT), centrifuged (700g, 5 minutes, RT) resuspended in DPBS+/+, and stained either with SYTO 13 or TO (25 μM) and anti-CD42b-DyLight 649 (1:50) simultaneously (15 minutes, RT, in the dark). Samples were washed with DPBS+/+ (700g, 5 min, RT), resuspended, in DPBS+/+ and analyzed using flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry data analysis and gating

Flow cytometry data were acquired using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with and analyzed using FlowJo version 10 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation with statistical analyses performed on GraphPad Prism (version 9). Two-tailed unpaired or paired t tests were used for comparisons of means between 2 groups. Repeated-measures 1-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction was applied for >2 groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. For clarity, RP detected by the RiboTag model are referred to as RiboTag-RP, those detected using SYTO 13 as SYTO-RP, and those detected using TO as TO-RP.

RNA sequencing sample preparation

Male C57BL/6J mice (10-14 weeks; Jackson Laboratories, no. 000664) underwent 30 minutes of ischemia followed by 48-hour reperfusion. Blood was collected, anticoagulated, and diluted 1:2 in Tyrode’s buffer (134mM NaCl, 0.34mM Na2HPO4, 2.9mM KCl, 12mM NaHCO3, 5mM glucose, and 0.35% bovine serum albumin; pH adjusted to 7.0). Washed platelets were isolated by sequential centrifugation (100g, 5 minutes, RT, no brake), the supernatant was removed to a fresh tube. The same was then repeated with a light brake (100g, 5 minutes, RT, brake 5) and the resulting supernatant transferred to a fresh tube. Finally, platelets were pelleted in the presence of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2; 1 μg/mL; Cayman) to avoid activation (700g, 5 min, RT, brake 9). Platelets were adjusted to 1 × 105/μL in Tyrode's buffer, and 1-mL aliquots were stained with rat anti-mouse CD41-BV421, anti-CD45-APC, anti-CD62P-PE, (all at 1:100), and SYTO 13 (25μM, 15 minutes, RT, dark). After centrifugation (700g, 5 minutes, RT, with PGI2), pellets were resuspended in 2 mL of Tyrode’s buffer. Platelet fixation was omitted to preserve RNA integrity.

Platelets were gated as CD41+, CD62P−, CD45−. RP and non-RP were defined as the top and bottom 20% of SYTO 13 fluorescence using a BD FACS Aria Fusion (70-μm nozzle). Approximately 4 × 106 platelets per population were collected into RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) with 1% β-mercaptoethanol, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C.

RNA-seq library preparation

RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the NuGEN Ovation SoLo Kit (Tecan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) were used for size selection. Library quality was assessed by high sensitivity assay (Agilent), with Tape station (Agilent). Libraries were sequenced in paired-end mode using Illumina NovaSeq. Raw data are available under BioProject PRJNA1290364.

Bioinformatics

Bioinformatic analyses were processed on the European Galaxy platform.25. Low-quality reads and adapters were removed using Trim Galore. Reads were aligned to Mus musculus (mm9) genome using RNA-STAR.26 Preribosomal Rn45s reads were excluded and PCR duplicates removed using RmDup. Transcript abundance was quantified using htseq-count,27 and differential expression analysis performed using DEseq228 (log2 fold change >1; q < 0.05). Gene function enrichment was performed using Cytoscape–ClueGo.29 Cell-cell ligand-receptor interactions were inferred using published single-cell RNA-seq data sets of mouse hearts 3 days after myocardial infarction30 and visualized in R.

Results

Successful detection of RP using RiboTag

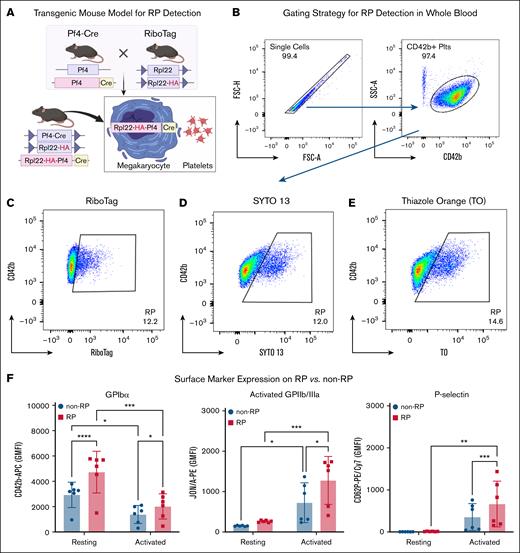

To detect circulating RP in mice, we used Pf4-Cre:RiboTag transgenic animals in which HA-tagged Rpl22 is selectively expressed in megakaryocytes and platelets (Figure 1A). Using flow cytometry, RP were readily identified based on HA (RiboTag) signal within the CD42b+ platelet gate, appearing as a distinct population from non-RP (Figure 1B-C). We compared this genetic approach with nucleic acid dye–based methods using SYTO 13 and TO, which similarly identified RP populations (Figure 1D-E). The specificity of the anti-HA antibody was confirmed in peripheral whole blood cells using an isotype control (supplemental Figure 2). Although the primary analysis in this study used male mice, RiboTag expression was confirmed in both sexes (supplemental Figure 3).

RiboTag-based identification and phenotypic characterization of RP in naïve mice. (A) Schematic of the Pf4-Cre:RiboTag transgenic mouse model, enabling lineage-specific HA tagging of ribosomes in megakaryocytes and their progeny. (B) Gating strategy for platelet identification in whole blood, based on singlet selection and CD42b positivity. (C-E) Representative flow cytometry plots showing RP detection using HA-RiboTag (RiboTag-RP) (C), SYTO 13 nucleic acid staining (SYTO-RP) (D), and TO staining (TO-RP) (E). (F) Expression of platelet surface markers in RiboTag-RP vs non-RP under resting and activated (PAR-4 agonist, 400 μM) conditions. Resting RiboTag-RP displayed higher expression of GPIbα (CD42b), and higher levels of activated GPIIb/IIIa (JON/A binding) and P-selectin (CD62P) following agonist-induced activation. Values from 6 mice are shown as GMFI ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). Statistical comparisons were made by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. rpl22, ribosomal protein l22.

RiboTag-based identification and phenotypic characterization of RP in naïve mice. (A) Schematic of the Pf4-Cre:RiboTag transgenic mouse model, enabling lineage-specific HA tagging of ribosomes in megakaryocytes and their progeny. (B) Gating strategy for platelet identification in whole blood, based on singlet selection and CD42b positivity. (C-E) Representative flow cytometry plots showing RP detection using HA-RiboTag (RiboTag-RP) (C), SYTO 13 nucleic acid staining (SYTO-RP) (D), and TO staining (TO-RP) (E). (F) Expression of platelet surface markers in RiboTag-RP vs non-RP under resting and activated (PAR-4 agonist, 400 μM) conditions. Resting RiboTag-RP displayed higher expression of GPIbα (CD42b), and higher levels of activated GPIIb/IIIa (JON/A binding) and P-selectin (CD62P) following agonist-induced activation. Values from 6 mice are shown as GMFI ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 6). Statistical comparisons were made by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. rpl22, ribosomal protein l22.

To further characterize the functional phenotype of naïve RP, we compared surface expression of platelet markers between RiboTag-RP and non-RP populations. In the resting state, RiboTag-RP displayed significantly elevated GPIbα (CD42b), exhibiting a 1.6-fold increase in geometric mean fluorescence intensity (GMFI) compared to non-RP (4895 ± 1567 vs 3022 ± 942; P < .0001; n = 6). This difference remained significant following activation with PAR-4 agonist (GMFI: 1958 ± 920 vs 1328 ± 667; P = .0153; n = 6; Figure 1F, left). Activated GPIIb/IIIa (CD41/61) expression increased significantly upon agonist stimulation in both groups indicating effective platelet activation. However, RiboTag-RP consistently demonstrated higher activated GPIIb/IIIa (1277 ± 595 vs 724 ± 492; P = .0294; n = 6; Figure 1F, middle). P-selectin (CD62P) surface levels were also significantly elevated in activated RiboTag-RP compared to their non-RP counterparts (GMFI: 885 ± 561 vs 468 ± 306; P = .001; n = 6; Figure 1F, right), suggesting increased α-granule content or release upon stimulation. These findings confirm that RP are not only identifiable by both RiboTag labeling and dye-based approaches, but also exhibit a distinct, activation-prone phenotype marked by enhanced expression of key platelet receptors.

Myocardial I/R injury induces a time-dependent increase in RP

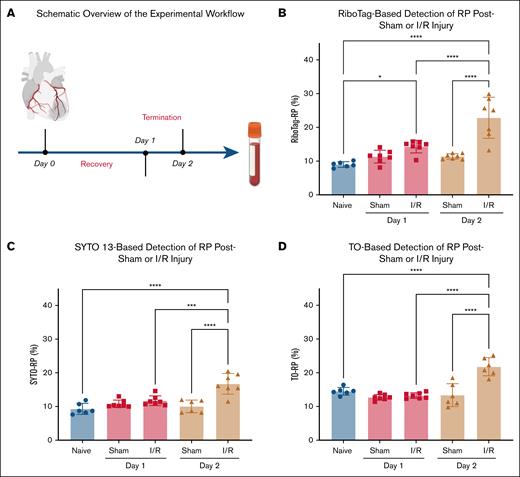

To investigate how myocardial I/R injury affects RP production, we used a murine model in which ischemia was induced by transient ligation of the LAD coronary artery for 30 minutes, followed by reperfusion for either 1 or 2 days (Figure 2A). Circulating RP levels were quantified using 3 independent methods: RiboTag-based labeling (RiboTag-RP), SYTO 13 staining (SYTO-RP), and TO staining (TO-RP).

Myocardial I/R injury triggers a time-dependent increase in circulating RP. (A) Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. Myocardial I/R injury was induced by 30-minute ligation of the LAD coronary artery followed by reperfusion for 1 or 2 days. Sham-operated mice underwent the same procedure without LAD ligation. RP were quantified at baseline and postsurgery using 3 independent flow-cytometric detection methods. (B) RiboTag-based detection of RP in whole blood revealed a modest increase in RiboTag-RP percentage on day 1 after I/R injury and a significant elevation by day 2, compared to sham controls. (C) SYTO 13 nucleic acid staining confirmed the I/R-induced increase in SYTO-RP levels at day 2, with no significant change on day 1. (D) TO staining yielded similar increase in TO-RP levels at day 2, supporting a robust thrombopoietic response after I/R injury. Data from 6 to 7 mice per group are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Myocardial I/R injury triggers a time-dependent increase in circulating RP. (A) Schematic overview of the experimental workflow. Myocardial I/R injury was induced by 30-minute ligation of the LAD coronary artery followed by reperfusion for 1 or 2 days. Sham-operated mice underwent the same procedure without LAD ligation. RP were quantified at baseline and postsurgery using 3 independent flow-cytometric detection methods. (B) RiboTag-based detection of RP in whole blood revealed a modest increase in RiboTag-RP percentage on day 1 after I/R injury and a significant elevation by day 2, compared to sham controls. (C) SYTO 13 nucleic acid staining confirmed the I/R-induced increase in SYTO-RP levels at day 2, with no significant change on day 1. (D) TO staining yielded similar increase in TO-RP levels at day 2, supporting a robust thrombopoietic response after I/R injury. Data from 6 to 7 mice per group are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001, ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

RiboTag analysis revealed a baseline circulating RiboTag-RP percentage of 9% ± 0.8% in unoperated mice (n = 6, Figure 2B). On day 1, RiboTag-RP increased to 14% ± 2% in I/R mice compared to 11% ± 2% in sham (n = 7; not significant; Figure 2B). By day 2, RiboTag-RP levels in myocardial I/R injury mice were significantly elevated (22% ± 6% vs 11% ± 1%; P < .0001; n = 7). SYTO-RP and TO-RP measurements confirmed this trend (Figure 2C-D). Using both dyes, no significant differences were detectable on day 1 but a robust elevation in SYTO-RP and TO-RP percentages by day 2 in I/R mice vs sham controls. These results indicate that RP increases progressively following I/R injury.

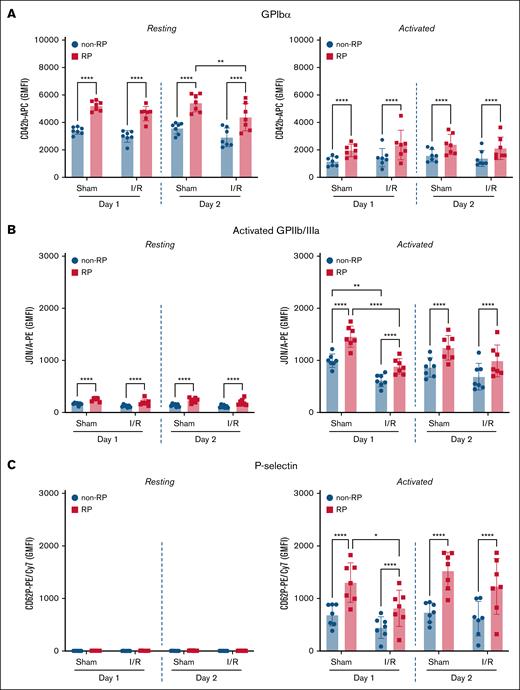

RP show elevated GPIbα and heightened responsiveness after I/R injury

To assess phenotypic differences between RP and non-RP in the setting of myocardial I/R injury, we performed RiboTag-based flow cytometry on day 1 and day 2 following ischemia induction. Surface expression of GPIbα (CD42b) was consistently higher on RiboTag-RP relative to non-RP on both days following I/R injury (day 1: 4644 ± 526 vs 2977 ± 426; day 2: 4382 ± 990 vs 2912 ± 678; n = 7; P < .0001). Similar differences were observed in sham-operated mice (day 1: 5211 ± 355 vs 3400 ± 263; day 2: 5414 ± 638 vs 3576 ± 417; n = 7; P < .0001; Figure 3A). Following PAR-4 stimulation, surface GPIbα decreased overall, as expected with activation, but remained significantly higher on RiboTag-RP compared with non-RP across all groups (Figure 3A, right).

RP display higher surface receptor expression and enhanced agonist responsiveness compared to non-RP, with altered phenotype after I/R injury. Flow-cytometric analysis was performed on whole blood from Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice 1 and 2 days after sham or myocardial I/R injury. (A) Surface expression of GPIbα (CD42b) was significantly higher in RiboTag-RP compared to non-RP under all conditions. RiboTag-RP retained significantly elevated levels at rest and after PAR-4 agonist stimulation. (B) GPIIb/IIIa activation (JON/A binding) was significantly greater in RiboTag-RP vs non-RP in both sham and I/R groups, although overall activation was modestly reduced after I/R injury. (C) Surface P-selectin (CD62P) expression was negligible at rest and markedly increased after PAR-4 stimulation, with RiboTag-RP consistently showing higher levels than non-RP. Data represent GMFI ± SD (n = 7). Statistical testing: 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

RP display higher surface receptor expression and enhanced agonist responsiveness compared to non-RP, with altered phenotype after I/R injury. Flow-cytometric analysis was performed on whole blood from Pf4-Cre:RiboTag mice 1 and 2 days after sham or myocardial I/R injury. (A) Surface expression of GPIbα (CD42b) was significantly higher in RiboTag-RP compared to non-RP under all conditions. RiboTag-RP retained significantly elevated levels at rest and after PAR-4 agonist stimulation. (B) GPIIb/IIIa activation (JON/A binding) was significantly greater in RiboTag-RP vs non-RP in both sham and I/R groups, although overall activation was modestly reduced after I/R injury. (C) Surface P-selectin (CD62P) expression was negligible at rest and markedly increased after PAR-4 stimulation, with RiboTag-RP consistently showing higher levels than non-RP. Data represent GMFI ± SD (n = 7). Statistical testing: 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Functional platelet responses paralleled these phenotypic differences. Baseline activated GPIIb/IIIa (JON/A binding) remained low across groups but was consistently higher on RiboTag-RP than on non-RP (Figure 3B, left). Upon PAR-4 stimulation, RiboTag-RP demonstrated significantly greater GPIIb/IIIa activation in both I/R and sham groups (Figure 3B, right). After I/R injury, RiboTag-RP showed a ∼1.4-fold higher activation compared to non-RP on both day 1 (883 ± 148 vs 614 ± 120), and day 2 (989 ± 305 vs 686 ± 257; P < .0001 for both, n = 7). Baseline P-selectin (CD62P) surface expression was minimal across all groups (Figure 3C, left). Following PAR-4 stimulation, RiboTag-RP displayed significantly higher CD62P exposure compared to non-RP in both I/R and sham conditions (Figure 3C, right). In I/R injury mice, RiboTag-RP showed a ∼1.8-fold increase on day 1 (RP vs non-RP: 814 ± 344 vs 446 ± 205), and a approximately twofold increase on day 2 compared to non-RP counterparts (RP vs non-RP: 1231 ± 532 vs 615 ± 329; P < .0001 for both, n = 7). Sham-operated mice exhibited similar differences between RP and non-RP.

To further assess the dynamics of RP activation following I/R injury, we measured activated GPIIb/IIIa and P-selectin exposure on PAR-4–stimulated RiboTag-RP across naïve, sham-operated, and I/R-injured mice. Activated GPIIb/IIIa showed no significant differences between RiboTag-RP from sham or I/R conditions on either day when compared to RiboTag-RP from naïve mice (supplemental Figure 4) However, RiboTag-RP from I/R mice showed a ∼40% reduction in GPIIb/IIIa activation compared to their sham counterparts on day 1 (P < .0001, n = 7). Furthermore, RiboTag-RP from sham-operated mice displayed significantly higher P-selectin expression on both day 1 and day 2 (approximately twofold higher) compared to naïve RiboTag-RP, whereas RiboTag-RP from I/R-injured mice showed no differences in P-selectin exposure relative to naïve mice on both days (supplemental Figure 4). Notably, activated RiboTag-RP from I/R mice showed ∼38% less P-selectin expression compared to their sham counterparts on day 1 (P =.0425, n = 7). Collectively, these results confirm that RP exhibit enhanced surface GPIbα expression and heightened agonist responsiveness compared to non-RP.

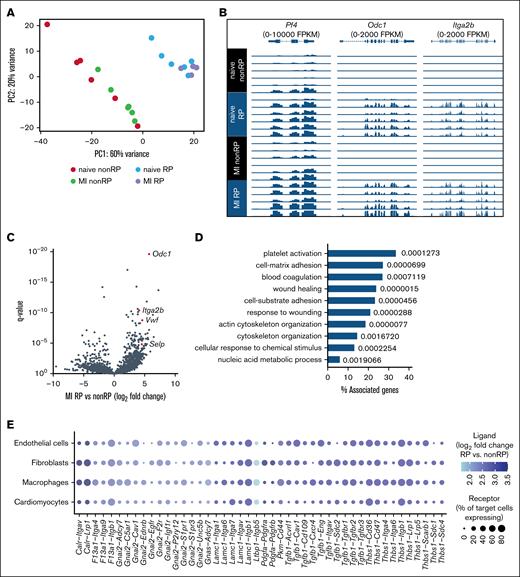

RP exhibit a distinct transcriptomic signature compared to non-RP

To define the molecular phenotype of RP in the context of myocardial I/R injury, we performed bulk RNA sequencing of flow cytometry–sorted SYTO-RP and non-RP from mice 48 hours after myocardial I/R injury. Principal component analysis revealed robust segregation between SYTO-RP and non-RP samples, with principal component 1 accounting for 60% of the total variance, underscoring substantial transcriptomic divergence between the 2 populations (Figure 4A).

RNA sequencing of RP and non-RP after experimental myocardial I/R injury. (A) Principal component analysis of gene expression in mouse RP and non-RP isolated by flow cytometry on day 2 after I/R injury based on SYTO 13 intensity (brightest vs dimmest 20% sorted in lysis buffer; n = 4-6 per group). (B) Expression of Pf4, Odc1, and Itga2b in SYTO-RP and non-RP. (C) Differential gene expression analysis comparing SYTO-RP and non-RP after myocardial I/R injury. (D) Top 10 biological processes enriched (with q values) among genes upregulated in SYTO-RP vs non-RP as derived from Gene Ontology. (E) Predicted cell-cell communication between RP and cardiac cells after I/R injury. Receptor expression in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and cardiomyocytes was derived from Molenaar et al.30 MI, myocardial infarction.

RNA sequencing of RP and non-RP after experimental myocardial I/R injury. (A) Principal component analysis of gene expression in mouse RP and non-RP isolated by flow cytometry on day 2 after I/R injury based on SYTO 13 intensity (brightest vs dimmest 20% sorted in lysis buffer; n = 4-6 per group). (B) Expression of Pf4, Odc1, and Itga2b in SYTO-RP and non-RP. (C) Differential gene expression analysis comparing SYTO-RP and non-RP after myocardial I/R injury. (D) Top 10 biological processes enriched (with q values) among genes upregulated in SYTO-RP vs non-RP as derived from Gene Ontology. (E) Predicted cell-cell communication between RP and cardiac cells after I/R injury. Receptor expression in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and cardiomyocytes was derived from Molenaar et al.30 MI, myocardial infarction.

Expression of platelet lineage markers such as Pf4, Itga2b, and the biosynthetic enzyme Odc1 was markedly enriched in RP (Figure 4B). Differential gene expression analysis identified a total of 436 transcripts significantly upregulated and 128 transcripts significantly downregulated in RP compared to non-RP (|log2 fold change| > 1, q < .05; Figure 4C; supplemental Table 3). Among the upregulated genes, several were associated with platelet activation and thromboinflammatory function, including Selp (P-selectin), Vwf (von Willebrand factor), and Itga2b (integrin αIIb), paralleling the enhanced surface GP expression and agonist responsiveness observed in functional assays. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of RP-upregulated genes revealed significant overrepresentation of biological processes linked to platelet activation, cytoskeletal reorganization, cell-substrate adhesion, coagulation, and wound healing (Figure 4D).

To further explore the potential of RP to engage in heterocellular interactions, we integrated ligand expression profiles from RP with receptor expression patterns from published single-cell RNA-seq datasets of cardiac endothelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and cardiomyocytes after ischemic injury.30 This analysis identified several candidate ligand-receptor interactions, including Tgfb1–Tgfbr2, Thbs1–Cd36, and Pdgfa–Pdgfra (Figure 4E). Among the candidate interactions, fibroblasts and macrophages appeared to be the most prominently engaged targets, although endothelial and cardiomyocyte signaling pathways also emerged as potential targets. Collectively, these findings establish RP as a transcriptionally distinct platelet subset with potential roles in both thromboinflammatory signaling and myocardial tissue remodeling following ischemic injury.

Discussion

We introduce and validate the first genetically engineered murine model for detecting and characterizing RP, a functionally distinct platelet subset. Leveraging a RiboTag-based strategy that labels megakaryocyte-derived ribosomes with an HA epitope, we provide a flow cytometry–compatible method to identify RP in whole blood. Our RiboTag system provides a genetically encoded, highly specific tag to detect RP (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 2). We validated this approach by comparing RP frequencies detected by RiboTag to those obtained using SYTO 13 and TO. Compared to nucleic acid–binding dyes, the RiboTag approach offers greater specificity by eliminating nonspecific staining and dye artifacts, although it requires genetic modification.

Consistent with prior studies in humans and animal models, we observed a significant increase in circulating RP following myocardial I/R injury.17,31,32 Using the RiboTag model in parallel with SYTO 13 and TO, we detected an early and progressive expansion of the RP population after myocardial I/R injury (Figure 2). This increase likely reflects enhanced thrombopoiesis in response to acute platelet consumption and inflammatory signaling. Elevated RP levels have been associated with infarct severity, platelet reactivity, platelet hyperactivity, and increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events.14,18,31 Our findings reinforce this concept and highlight the RiboTag system as a sensitive tool for detecting dynamic changes in platelet turnover.

We show that RP display significantly higher levels of GPIbα compared with non-RP, both at baseline and following PAR-4 stimulation (Figure 3A). GPIbα is a key adhesion receptor mediating platelet tethering under high shear, and its elevated expression in RP may enhance thrombotic potential. GPIbα expression decreased following myocardial I/R injury at baseline and showed a dramatic reduction after PAR-4 ex vivo agonist stimulation, indicating significant modulation of GPIbα under these conditions. This reduction may result from a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 (ADAM17) -mediated shedding of the GPIbα ectodomain, also known as glycocalicin. Others have shown that this process can be stimulated by platelet activation.33,34

The pronounced increase in GPIIb/IIIa activation observed in RP following PAR-4 stimulation across sham and I/R conditions underscores their hyperreactive phenotype (Figure 3B). This elevation is consistent with clinical observations showing higher GPIIb/IIIa expression on platelets from I/R patients compared to controls.35 Additionally, the heightened responsiveness of RP supports the concept that GPIIb/IIIa plays a central role in mediating platelet-endothelium interactions under pathological flow conditions. Indeed, antagonizing GPIIb/IIIa during reperfusion has been shown to confer cardioprotection in animal models by reducing platelet adhesion and infarct size.7,9,36 P-selectin, a marker of α-granule release, is implicated in leukocyte recruitment, endothelial activation, and platelet-mediated inflammation.37 The increased surface exposure in RP further shows the proinflammatory character of this subpopulation (Figure 3C).

To gain mechanistic insights into the functional differences between RP and non-RP, we performed bulk RNA sequencing of sorted platelet populations 48 hours after I/R using SYTO 13 to avoid the RNA degradation associated with fixation/permeabilization required for HA staining.14,16 Principal component analysis demonstrated clear segregation between RP and non-RP, confirming distinct transcriptional signatures. Canonical platelet markers such as Pf4 and Itga2b were enriched in RP, validating their megakaryocytic origin and immature status. We identified upregulation of genes involved in cytoskeletal remodeling (Acta1, Pkn2, Trpc6), adhesion (Vwf, Selp), and inflammatory signaling (Tgfb1, Thbs), many of which are known to influence platelet function and intercellular communication.38-40 Gene Ontology analysis revealed significant enrichment in biological processes including platelet activation, integrin signaling, and wound response pathways. These findings suggest that RP are pre-equipped with a transcriptional response capacity tailored for thromboinflammatory activity and tissue interaction. Although anucleate, young platelets retain a residual transcripts and translation capacity modulating their functional responses.13,14 Our data provide one of the first comprehensive molecular maps of RP during myocardial I/R injury and lay the groundwork for future studies into their regulatory networks. Although traditionally viewed as hemostatic, our evidence supports broader platelet roles in inflammation, fibrosis, and myocardial healing.31,41 RP, given their enhanced responsiveness and gene expression profile, may amplify these effects. Our ligand-receptor interaction analysis indicated that RP-derived mediators such as transforming growth factor β1, thrombospondin-1, and platelet-derived growth factor may interact with receptors expressed by endothelial cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, and cardiomyocytes, suggesting a role for RP in modulating post I/R myocardial remodeling. Although we did not directly measure infarct size or remodeling outcomes, our findings support a model in which RP contribute to the cellular cross talk that shapes myocardial healing following I/R injury. Whether RP activity promotes repair or contributes to adverse fibrosis and inflammation remains to be determined.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, detection of RiboTag-positive RP requires fixation and permeabilization to allow intracellular staining of the HA epitope. This limits the use of this model for in vivo imaging or real-time tracking of RiboTag-RP and restricts its compatibility with ex vivo applications that require viable platelets (eg, adoptive transfer). Second, our analysis focused on early time points after I/R injury (24-48 hours), which does not capture the full kinetics of platelet turnover or the later phases of tissue remodeling. Third, quantification of GPIbα expression was performed within CD42b+-gated platelet events, which may influence mean fluorescence intensity estimates. Fourth, although ligand-receptor interaction analysis suggests potential communication between RP and cardiac cell types, these remain computational predictions requiring functional validation. Despite these limitations, this study introduces a genetically encoded model for RP detection and provides foundational insights into the phenotype and function of RP during myocardial I/R injury.

Conclusions

We present a genetically encoded model for detecting RP and apply it to uncover dynamic and functional changes in RP following myocardial I/R injury. Our findings establish RP as a hyperreactive, transcriptionally distinct platelet subset with the potential to influence thromboinflammatory signaling and myocardial remodeling. This platform lays the foundation for future mechanistic studies and opens new avenues for investigating platelet heterogeneity in cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Lighthouse Core Facility for technical support. Some figures were created in biorender.com. Hamm, P. (2025) https://biorender.com/x1wv22l.

This study was part of SFB1425, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation; project 422681845). The Lighthouse Core Facility is funded in part by the Medical Faculty, University of Freiburg (projects 2023/A2-Fol and 2021/B3-Fol), and the DFG (project number 450392965).

Authorship

Contribution: M.A. Hamad designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; N.S. and K.K. supervised the project and contributed to experimental design and data interpretation; A.L. performed bioinformatic analysis; J.M., S.P.F., P.I., M.Z., and L.A. contributed to data collection; M.A. Hollenhorst, P.K., and T.G.N. provided intellectual input and revised the manuscript; D.D. conceived the study and supervised the project; and all authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for T.G.N. is Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland.

Correspondence: Muataz Ali Hamad, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, 77 Ave Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115; email: mahamad@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

RNA sequencing data have been deposited in BioProject (identification no. PRJNA1290364).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.