TO THE EDITOR:

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare but life-threatening thrombotic disorder characterized by widespread microvascular thrombosis, severe thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia. It results from a deficiency of ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motifs 13), either due to mutations in the ADAMTS13 gene (congenital TTP) or due to autoantibodies that inhibit or accelerate clearance of ADAMTS13 (immune-mediated TTP [iTTP]). ADAMTS13 cleaves von Willebrand factor (VWF) to regulate its multimer size. In the absence of ADAMTS13, ultralarge VWF multimers accumulate and spontaneously bind platelets.1,2 The resulting VWF- and platelet-rich microthrombi occlude the systemic microvasculature, causing life-threatening ischemic organ crises such as stroke and myocardial infarction.3,4 Prompt diagnosis and treatment with plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy are critical to prevent organ damage and reduce mortality. In Japan, caplacizumab was approved by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in 2022, 3 years after approval by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, and has been incorporated into national treatment guidelines as an add-on to standard therapy since 2023.

The regulation of VWF size and activity is essential to maintain vascular integrity and prevent excessive thrombosis. In addition to cleavage by ADAMTS13, VWF can be proteolyzed by plasmin. We previously discovered that plasminogen activation occurs during TTP attacks and suggested that hypoxia-induced endothelial activation drives local urokinase-type plasminogen activator-dependent plasmin generation.5 Although endogenous plasmin alone is insufficient to resolve VWF-platelet complexes in the absence of ADAMTS13, we recently showed that the plasmin-mediated cleavage of VWF generates distinct fragments that may serve as a biomarker of microvascular thrombosis.6,7

Our recent work introduced a novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that specifically detects plasmin-cleaved VWF (pcVWF), demonstrating its potential as a tool to assess plasmin-mediated proteolysis of VWF in various thrombotic conditions.7 Elevated pcVWF levels were observed in patients with acute iTTP. However, the initial study included only a small number of patients (n = 26) and lacked detailed clinical data.7 To address this limitation, we validated the assay in a larger, well-characterized iTTP cohort. We analyzed pcVWF levels during acute attacks using plasma samples from the unique Japanese iTTP registry and correlated these with clinical and laboratory parameters. Samples were collected at the Department of Blood Transfusion Medicine at Nara Medical University, under the approval of the ethics committee of the Nara Medical University and conducted under the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. In this study, 83 plasma samples from patients with iTTP obtained during the acute phase before initial treatment were randomly selected. All samples were obtained at the patients’ first iTTP episode and were collected between 2004 and 2020, which is before the approval of caplacizumab in Japan. According to the Japanese diagnostic and treatment guidelines for TTP in 2023, iTTP was defined by the presence of severe thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, along with a marked deficiency in ADAMTS13 activity (<10% of normal levels) and detectable ADAMTS13 inhibitors.8 Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1, whereas details on received therapies and causes of death for the 15 patients who died during the acute phase are listed in supplemental Table 1.

The levels of pcVWF and VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) were determined using ELISA.7 To compare pcVWF ELISA results of patients with acute iTTP with those of healthy donors, plasma samples from healthy volunteers (n = 43; 23 females, 20 males; median age, 42 years; interquartile range, 32.0-55.0) were used. These samples were collected between 2023 and 2025 and prepared from blood samples acquired through venous phlebotomy with the ethical approval of the University Medical Center Utrecht. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk, D’Agostino and Pearson, and Anderson-Darling tests. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. Correlations were assessed using Spearman rank correlation coefficient. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

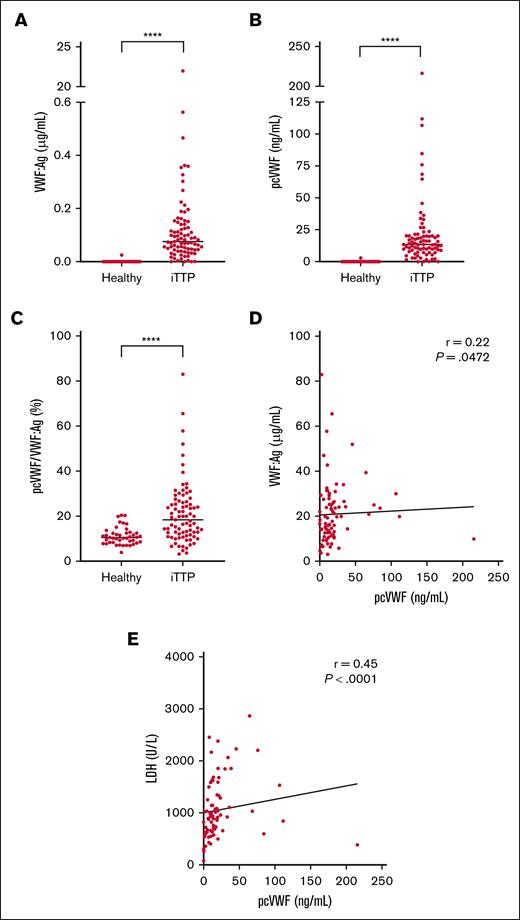

VWF:Ag levels were elevated in patients with acute iTTP (18.4 μg/mL [11.8-26.2]) compared to healthy controls (10.4 μg/mL [8.3-12.4]) (P < .0001; Figure 1A), which is a common finding in acute TTP, in the context of endothelial activation and the absence of ADAMTS13. Accordingly, pcVWF levels were significantly elevated in patients with acute iTTP (13.5 ng/mL [8.4-20.3]) compared to healthy donors (0 ng/mL [0-0]) (P < .0001; Figure 1B), confirming the presence of pcVWF during acute TTP episodes. The ratio of pcVWF over VWF:Ag demonstrates that the elevation of pcVWF is not merely a consequence of increased VWF:Ag levels, but rather a result of a greater fraction of VWF being cleaved by plasmin (P < .0001; Figure 1C). To further illustrate this relationship, we plotted VWF:Ag levels against pcVWF levels for each individual patient (Figure 1D), which showed a weak correlation (r = 0.22; P < .05).

Elevated pcVWF levels in patients with acute iTTP. (A) VWF:Ag levels and (B) pcVWF levels were measured using ELISA in healthy donors (n = 43) and patients with acute iTTP (n = 83). (C) pcVWF levels were divided by VWF:Ag to determine the fraction of pcVWF relative to total VWF:Ag. Graphs show individual values with medians. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk, D’Agostino and Pearson, and Anderson-Darling tests. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) VWF:Ag levels plotted against pcVWF levels for each patient. (E) LDH levels from routine hospital testing were plotted against pcVWF. Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the correlations in panels D-E. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Elevated pcVWF levels in patients with acute iTTP. (A) VWF:Ag levels and (B) pcVWF levels were measured using ELISA in healthy donors (n = 43) and patients with acute iTTP (n = 83). (C) pcVWF levels were divided by VWF:Ag to determine the fraction of pcVWF relative to total VWF:Ag. Graphs show individual values with medians. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk, D’Agostino and Pearson, and Anderson-Darling tests. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. (D) VWF:Ag levels plotted against pcVWF levels for each patient. (E) LDH levels from routine hospital testing were plotted against pcVWF. Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to evaluate the correlations in panels D-E. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Subsequently, we aimed to correlate pcVWF levels to clinical characteristics from the cohort of patients with iTTP. Given that all patients were severely thrombocytopenic, no correlation could be observed between pcVWF levels and platelet counts (r = −0.16; P = .14). A moderate correlation was observed between pcVWF and lactate dehydrogenase levels (r = 0.45; P < .001), reflective of end-organ damage, intravascular hemolysis, or both (Figure 1E). However, no significant correlation was observed between pcVWF levels and creatinine (r = 0.17; P = .13) or total bilirubin (r = 0.12; P = .29). In addition, the Gray test was used in survival analysis to compare the cumulative incidence of TTP-related death in the presence of competing risks (ie, non–TTP-related death). When patients were divided into 2 groups based on pcVWF levels, low (below the median of 13.5 ng/mL) and high (above the median), no difference was observed in the cumulative risk of 1-year TTP-related death between the groups (P = .915). This indicates that pcVWF is a biomarker of acute disease without any predictive value for future TTP-related deaths.

Some aspects of the study design should be considered. Healthy controls were recruited in the Netherlands rather than Japan, which may introduce ancestry-related differences. Although variation in VWF:Ag levels across populations has been described, potential differences for pcVWF are not yet known. ABO blood group data were not available for the controls, and the control cohort was younger on average than the patients, although sex distribution was comparable. Although these factors warrant attention in future studies, they are unlikely to account for the large differences in pcVWF observed between patients and controls.

In conclusion, our study provides further evidence of the significance of pcVWF as a biomarker of ongoing microvascular thrombosis. It remains unclear whether plasmin activation during TTP is simply a byproduct of severe acute episodes and endothelial damage or whether it influences disease severity at any time during the course of the disease. The novel thrombolytic agent Microlyse leverages this system by locally enhancing plasmin activation at sites of microvascular obstruction, effectively breaking down VWF-rich microthrombi in mouse models of TTP and stroke.9,10 Our current findings underscore the need for future studies measuring pcVWF in other cohorts of patients with thrombosis with enhanced ultralarge-VWF accumulation, such as ischemic stroke, sepsis, and preeclampsia. This will help to improve our understanding of the clinical relevance of plasmin-mediated VWF degradation and to adjust treatment strategies to support the local degradation of VWF-rich microthrombi.

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by a research grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (grant number 20FC1024 [M.M.]).

Contribution: H.E.O., C.T., and K.S. designed the study; H.E.O. performed the experiments; K.S. and M.M. recruited the patients; H.E.O., C.T., K.V., M.M., and K.S. analyzed the data and interpreted the results; H.E.O., C.T., and K.S. wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.V. received speaker fees from Sanofi and participated in the advisory boards of Takeda. M.M. provided consultancy services for Takeda, Alexion Pharma, and Sanofi; received speaker fees from Takeda, Alexion Pharma, Asahi Kasei Pharma, and Sanofi; and received research funding from Alexion Pharma, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Asahi Kasei Pharma, and Sanofi. K.S. received speaker fees from Sanofi and participated in the advisory boards of Takeda and Alexion Pharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hinde El Otmani, CDL Research, University Medical Center Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, 3584 CX Utrecht, The Netherlands; email: h.elotmani-2@umcutrecht.nl.

References

Author notes

Data are available from the corresponding author, Hinde El Otmani (h.elotmani-2@umcutrecht.nl), on request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.