Key Points

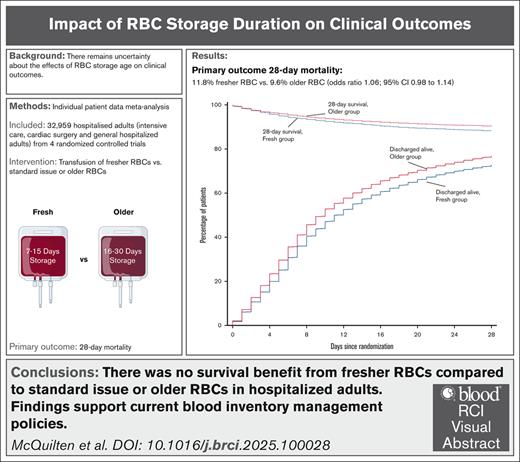

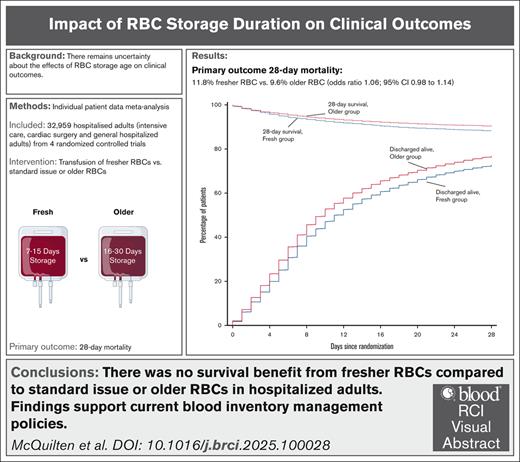

In an individual patient data meta-analysis (n = 33 549), there was no survival benefit from transfusing fresher vs older RBC units.

Findings support current blood inventory management policies and are applicable to most hospitalized adults.

Visual Abstract

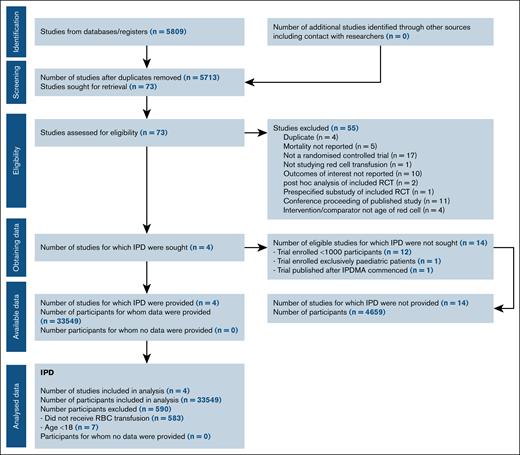

Randomized trials reported no benefit from transfusion of red blood cell (RBC) units stored for shorter durations compared with standard care. However, there was insufficient evidence to exclude harms at extremes of storage age or explore subgroup differences. We performed an individual patient data meta-analysis to determine the effect of fresher vs older RBC transfusion on 28-day mortality in hospitalized adults. Individual patient data were sought from clinical trials that randomized >1000 adult patients. For the meta-analysis, we used a logistic regression model with a trial-specific fixed effect. Four studies provided individual data from 33 549 patients enrolled from March 2009 through December 2016 from 12 countries. After exclusions, 32 959 (98.2%) patients were included in the analysis. Patients received a median of 2 (interquartile range [IQR], 1-4) RBC units with a storage duration of 10 (IQR, 7-15) days in the fresh and 23 (IQR, 16-30) days in the older group. Death occurred in 1446 of 12 236 patients (11.8%) in the fresher and 1984 of 20 572 patients (9.6%) in the older group (odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.98-1.14; P = .124). No significant subgroup differences were identified. We found an association between receiving 1 and ≥2 RBC units with storage age of ≤7 days and higher mortality (odds ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.35; P = .024; and odds ratio, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32; P = .015; respectively), but not with any RBC units with storage age of ≥35 days. Adjusted analyses confirmed these findings. Our findings support current blood inventory management policies and are applicable to most hospitalized adults. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT05482737.

Introduction

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are one of the most commonly undertaken medical interventions worldwide.1 RBC units can be stored up to 42 days (35 in some jurisdictions). Storage of RBCs has supported more effective inventory management, but there have been concerns about the relative clinical benefits and risks of transfusing RBCs at younger (“fresher”) or prolonged storage ages. During storage after donation, RBCs undergo well-described biochemical and biophysical changes, which may alter their ability to traverse blood vessels, deliver oxygen, and survive in vivo,2 whereas the storage medium accumulates inflammatory and bioreactive mediators.1 Recent metabolomic research has identified particular metabolic alterations occurring in specific storage-age windows, but the clinical relevance of these changes is unknown.1

Previous observational studies suggested an association between transfusion of older RBCs and worse clinical outcomes.3 More recently, a target trial emulation performed using a real-world data set, suggested that transfusion of RBCs stored for >1 or 2 weeks was associated with increased risk of mortality and thromboembolism.4 However, observational studies have significant limitations, including unmeasured cofounding, time-varying confounding (timing and volume of transfusions may influence both exposure and outcome), immortal time bias, and misclassification of exposure. In response to the preclinical and observational data, a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to evaluate the effect of RBC storage age on clinical outcomes.

Trial level meta-analysis of 16 RCTs found no statistically significant differences in effects of transfusing longer-stored RBCs compared with shorter storage ages on mortality.5 However, the confidence intervals (CIs) of the pooled estimate included the potential for 1% to 2% benefit, and up to 9% harm from fresher RBC transfusion. None of these RCTs had sufficient numbers of patients receiving RBCs at either storage age extreme (storage age of ≤7 days or ≥35 days) to explore possible consequences of RBC transfusion at these limits. Given that RBC transfusion is a very common intervention, evidence of harm at different storage ages would have significant implications for patients and blood transfusion services globally.

Our goal was to pool individual patient data from major RCTs to determine the effect of fresher vs older RBC transfusion on 28-day mortality in hospitalized adults. Using an individual patient data meta-analysis (IPDMA), rather than a conventional meta-analysis, would allow us to improve the precision of treatment estimates, explore treatment effects in major subgroups not possible in previous meta-analyses, explore the effect of transfusion of RBCs at the extremes of storage age, and further strengthen any inferences of benefit or harm.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an IPDMA and report our results according to the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) of individual patient data statement.6

The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT05482737), a priori hypotheses were prespecified in The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (937699 Steiner National Institutes of Health), and an a priori statistical analysis plan completed; the full protocol and statistical analysis plan is available with the text of this article. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and had approval from Monash University Human research ethics committee (project identity no., 23584).

Study search and selection process

We identified eligible studies from our published systematic review,5 which conducted searches to 21 July 2017 in Medline (OvidSP), 20 July 2017 in EMBASE (OvidSP), and June 2017 in the Cochrane Library (supplemental). We updated the database searches on 20 October 2022 to assess the representativeness of included studies in our IPDMA (but did not seek individual patient data from any trials published after our cutoff date, due to completion of our grant funding at this time).

Study inclusion

The search criteria and methods for study selection for our previous systematic review have been published elsewhere.5 In brief, studies were considered eligible if they were RCTs that enrolled hospitalized patients and compared transfusion of fresher RBCs with transfusion of standard issue (“first-in first-out” RBC unit issue policy) or older RBCs. Eligible studies for our IPDMA were those that enrolled >1000 adult patients and agreed to contribute trial data. This was partly based on our previous systematic review, in which trials of >1000 participants contributed >95% of all included patients in the meta-analysis.

Study population

A modified intention-to-treat population including only patients aged >17 years who received at least 1 RBC transfusion were included for all analyses.

Data collection processes

We obtained approval to access individual patient data from each of the trials from their relevant ethics committees and regulatory agencies. Once approvals were received and data transfer agreements in place, we securely transferred the data to Monash University for data cleaning and analysis.

Before start of this analysis, the case report forms, data dictionaries, and study protocols were compared, and similarities and dissimilarities discussed across the trial teams to inform the final combined data set. Similar variables and parameters were checked for consistency across the trials before finally being imported into the combined database.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 28-day mortality, defined as any death occurring in the first 28 days after randomization. Secondary outcomes included (1) time until death (censored at day 28), (2) patients discharged alive from the hospital at day 28, and (3) hospital length of stay (censored at day 28). The time zero of all outcomes was the date of randomization.

Analysis plan

All analyses were conducted in the modified intention-to-treat population described earlier and were performed according to treatment allocation. The study was performed using 1 stage modeling with trial as a fixed effect.7 Heterogeneity between trials was determined by fitting a fixed interaction term between treatment arm and trial, whereas overall treatment effect was reported with trial treated as a fixed effect without the interaction term. A sensitivity analysis was performed using a mixed-effects logistic regression with trial as a random effect, to assess the impact of modeling choices on the estimated treatment effect and its generalizability on the primary outcome. Primary analyses were conducted with patients retained in their original, randomly assigned groups and were unadjusted for baseline risk factors. Additional analyses adjusted for age, sex, patient ABO blood group, and location at randomization (in or outside of intensive care units) were performed. In addition, complete case analysis was carried out for all the outcomes.

Baseline characteristics are expressed as counts and percentages and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The primary outcome was analyzed using a logistic regression model and reported as odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs. The incidence of patients discharged alive from the hospital at day 28 was assessed using cumulative incidence curves and reported as subdistribution hazard ratios and 95% CIs estimated from a Fine-Gray competing risk model with death before discharge treated as competing event. Time until death at day 28, intensive care unit and hospital length of stay were assessed with median regression models reported as median difference and 95% CI, and performed using an interior point algorithm and with standard errors calculated using bootstrap with 1000 replications. In addition, time to 28-day mortality and hospital discharge alive was plotted in cumulative incidence curves.

Prespecified subgroups according to baseline characteristics were age (<65 vs ≥65 years), sex (male vs female), intensive care unit admission at randomization, ABO group (A, B, AB, or O), past history of stroke, past history of diabetes, current surgical admission, past history of cardiovascular disease, use of renal replacement therapy, and current cardiovascular surgery. Given differences in blood supply management between jurisdictions, we also performed a subgroup analysis by country. To determine whether the relationship between treatment and the primary outcome differs between these subgroups, fixed interaction terms between treatment and subgroup were added in the main model for the primary outcome. To further ascertain whether the treatment-subgroup interaction varied between trials, a three-way fixed interaction between trial, treatment, and subgroup was also reported.

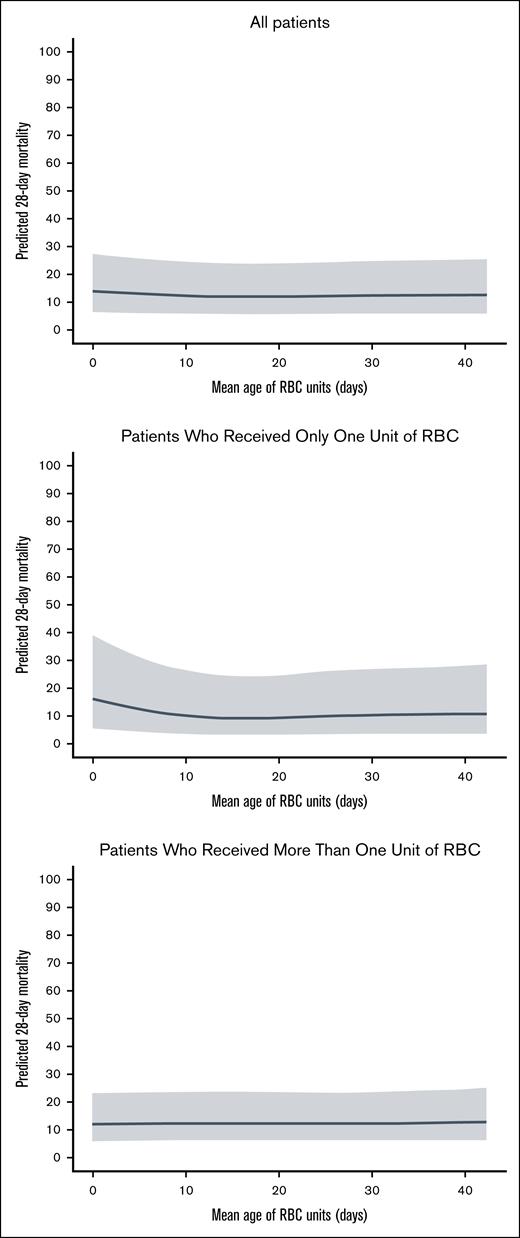

We performed an exploratory analysis to compare the primary outcome in patients who received RBCs at the extremes of storage age. To explore the effect of transfusing fresh RBCs, we compared outcomes in patients allocated to the fresh group who received 1 unit of RBCs with storage age of ≤7 days and ≥2 RBC units with storage age of ≤7 days with all patients allocated to the older group (irrespective of whether they received RBCs with storage age of ≤7 days). We repeated this analysis, using a cutoff of ≤10 days to define fresher RBCs. Then, to explore the effect of transfusing older RBCs, we compared outcomes in those patients allocated to the older group who received 1 and ≥2 RBC units with storage age of >35 days with all patients allocated to the fresh group (irrespective of whether they received a transfusion of RBCs with storage age of >35 days). Finally, to explore possible nonlinear relationship between RBC storage duration and mortality, we performed a restricted cubic spline logistic regression model assessing the association between the mean storage duration of transfused RBC units and 28-day mortality, adjusted for the number of units transfused (single vs multiple), and with trial included as a random effect. We present these results visually to explore potential nonlinear relationships: (1) 1 including all patients, adjusted for number of units transfused; (2) 1 restricted to patients who received only 1 RBC unit; and (3) 1 restricted to patients who received >1 unit.

Hypothesis tests were 2-sided, with a significance level of 5%. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using R (R, version 4.3.3, Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study selection and IPD obtained

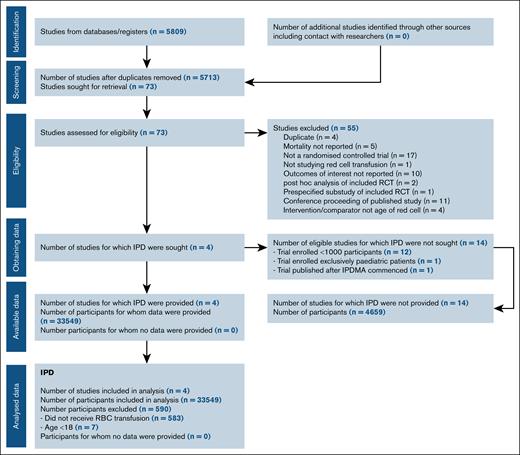

Figure 1 shows PRISMA individual patient data study flow. Four studies were included: ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation; ISRCTN44878718),8 RECESS (Red-Cell Storage Duration Study; NCT00991341),9 INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management; ISRCTN08118744),10 and TRANSFUSE (Standard Issue Transfusion versus Fresher Red-Cell Use in Intensive Care; ACTRN12612000453886).11 These 4 trials included 95% (n = 33 549) of all enrolled patients in the previous meta-analysis.5 Twelve trials that individually enrolled <1000 patients who had experienced trauma,12,13 were admitted to intensive care units,14,15 underwent cardiac surgery,16,17 or were hosptialized,18 or enrolled pediatric patients,19-23 were excluded. Only 1 trial that enrolled >1000 adult patients was identified after our cutoff date.24 Further details of the included and excluded studies12-26 are outlined in supplemental Table 1. Risk of bias of included studies has been reported in our previous meta-analysis,5 in which the included trials were assessed as low risk of bias, with the exception of blinding of participants and personnel in 2 studies.9,10

Patients

From March 2009 through December 2016, the 4 trials enrolled 33 549 patients at 162 centers in Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Finland, Ireland, Israel, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, United Kingdom, and the United States. After exclusion of patients aged <17 years and patients who did not receive an RBC transfusion, 32 959 (98.2%) were included in the primary analysis (supplemental Figure 1). There were no important issues identified in checking the individual patient data. Patient characteristics at baseline are reported in Table 1. Patients’ allocation was performed in a 1:2 ratio in the INFORM study, and in a 1:1 ratio in the other 3 trials.

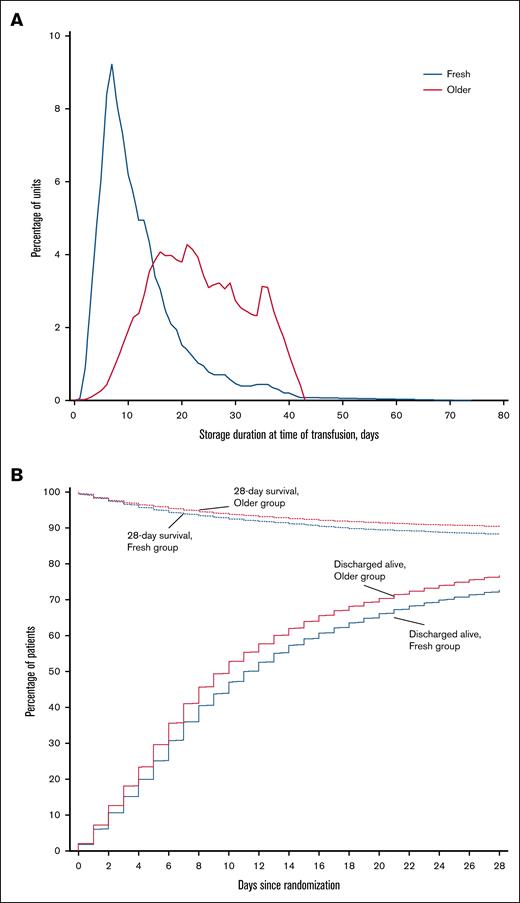

Intervention

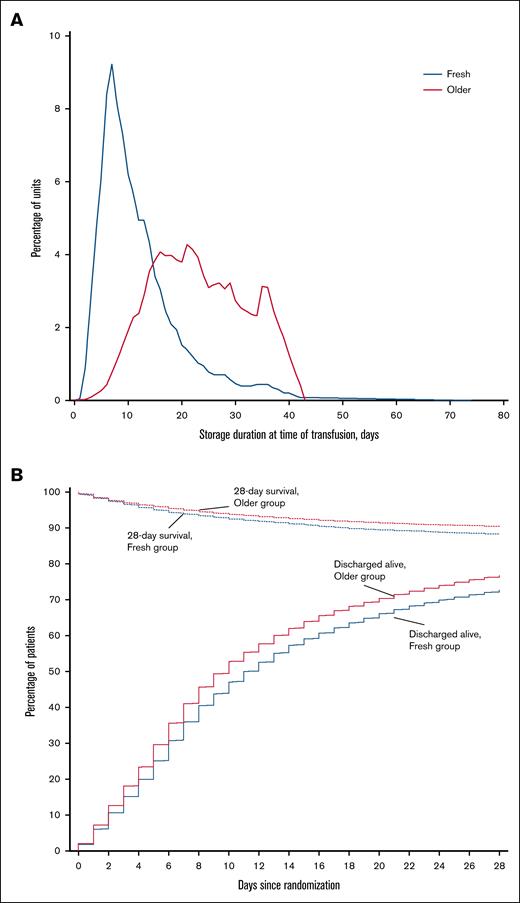

Characteristics of the intervention are reported in Table 2. Patients in each group received a median of 2 (IQR, 1-4) RBC units. The median storage duration of transfused RBCs per patient was 10 (IQR, 7-15) days in the fresh group and 23 (IQR, 16-30) days in the older group (P < .001; Figure 2A).

Storage duration of RBC units and survival to hospital discharge according to study group. (A) Storage duration of RBC units by study group. The blue line indicates the distribution of storage durations for RBC units transfused in participants who were randomly assigned to receive fresher RBC units, and the red line indicates the distribution of storage durations for RBC units transfused in participants assigned to receive older RBC units. (B) Patients who survived to hospital discharge and were discharged alive during the first 28 days after randomization. Patients were censored at day 28 after randomization.

Storage duration of RBC units and survival to hospital discharge according to study group. (A) Storage duration of RBC units by study group. The blue line indicates the distribution of storage durations for RBC units transfused in participants who were randomly assigned to receive fresher RBC units, and the red line indicates the distribution of storage durations for RBC units transfused in participants assigned to receive older RBC units. (B) Patients who survived to hospital discharge and were discharged alive during the first 28 days after randomization. Patients were censored at day 28 after randomization.

Primary outcome

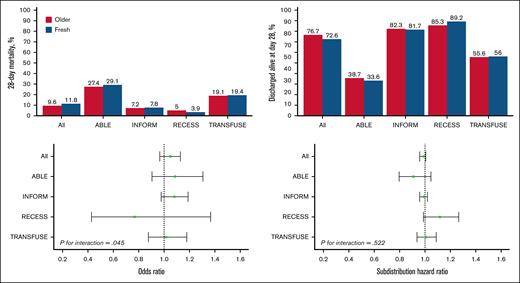

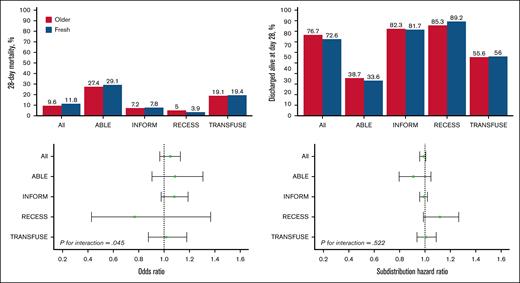

There was no statistically significant difference in 28-day mortality between the 2 groups (Table 3). Death occurred in 1446 of 12 236 patients (11.8%) in the fresh group and in 1984 of 20 572 patients (9.6%) in the older group (Figure 2B; Table 3). After accounting for the studies as fixed effect, the OR was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.98-1.14; P = .124) and there was no statistically significant interaction with respect to treatment effect among the trials (P = .645; Figure 3). After adjustment for age, sex, blood group, and intensive care unit admission at randomization, the results were similar, with an OR of 1.05 (95% CI, 0.97-1.13; P = .235; supplemental Table 2).

Heterogeneity of treatment effect according to studies. Top graphs, percentage of 28-day mortality (left top) and discharged alive at day 28 (right top) in the pooled data set and according to included studies. Bottom graphs, OR of fresh vs older for 28-day mortality (left bottom) and subdistribution hazard ratio of fresh vs older for discharged alive at day 28 (right bottom).

Heterogeneity of treatment effect according to studies. Top graphs, percentage of 28-day mortality (left top) and discharged alive at day 28 (right top) in the pooled data set and according to included studies. Bottom graphs, OR of fresh vs older for 28-day mortality (left bottom) and subdistribution hazard ratio of fresh vs older for discharged alive at day 28 (right bottom).

Secondary outcomes

Time until death, percentage of patients discharged alive from hospital by day 28, and hospital length of stay were similar between groups (Table 3; Figure 2B). There was no statistically significant interaction with respect to treatment effect among the trials in relation to any of the secondary outcomes (Figure 3). Adjusted analyses confirmed the main findings (supplemental Table 2).

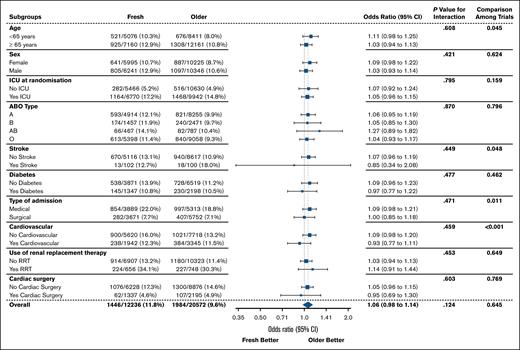

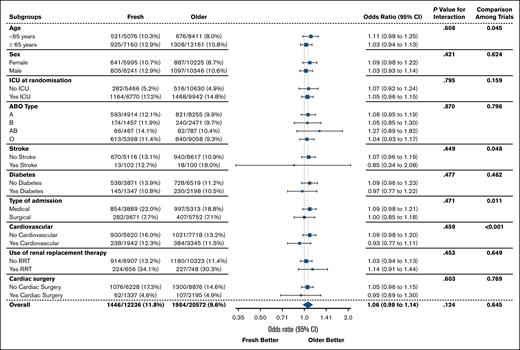

Subgroup analyses

Of the prespecified patient subgroup analyses, none had significant interactions (Figure 4). There was no evidence of benefit associated with fresh RBCs according to age, place of admission at randomization, ABO blood group, presence of comorbidities, or use of renal replacement therapy.

Twenty-eight–day mortality according to patient subgroup. ICU, intensive care unit; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

Twenty-eight–day mortality according to patient subgroup. ICU, intensive care unit; RRT, renal replacement therapy.

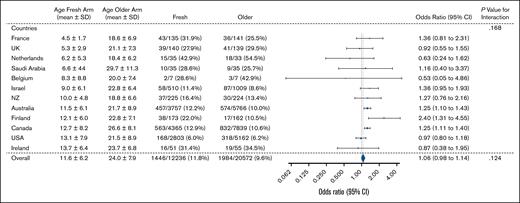

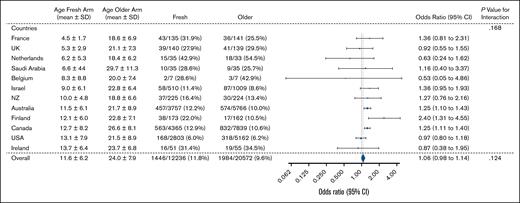

Subgroup analysis by country is shown in Figure 5. The mean (±standard deviation) age of RBCs in the fresh group varied by country, from 4.5 ± 1.7 days in France to 13.7 ± 6.4 days in Ireland. The 3 countries with the largest recruitment were Canada (n = 12 204), Australia (n = 9523), and the United States (n = 7965). Overall, there was no significant evidence of heterogeneity by country. However, in both Canada and Australia, the effect estimate favored the older group (Canada: OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11-1.40; and Australia: OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.43). In contrast, there was no difference in the primary outcome in the United States subgroup (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.80-1.18).

Twenty-eight–day mortality according to country of treatment. NZ, New Zealand; SD, standard deviation; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States.

Twenty-eight–day mortality according to country of treatment. NZ, New Zealand; SD, standard deviation; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States.

Sensitivity analysis

In the mixed-effect logistic regression of the primary outcome with trial as a random effect, the unadjusted OR was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.98-1.14; P = .123) and the adjusted OR was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.97-1.13; P = .231).

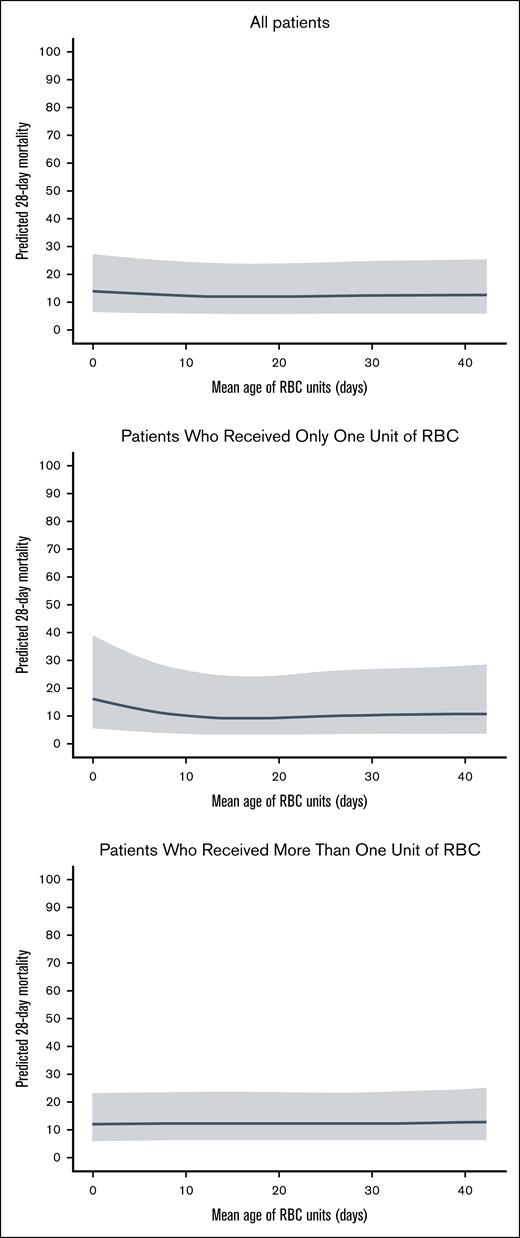

Exploratory analyses

The impact of transfusion of RBCs at the extremes of storage age are shown in Table 4. In the fresh group, patients who received transfusion with 1 RBC unit stored for ≤7 days (n = 1909) and ≥ RBC units stored for ≤7 days (n = 2876) had an increased risk of 28-day mortality compared with all patients allocated to the older group (irrespective of the age of RBCs they received), after accounting for the studies as a fixed effect (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02-1.35; P = .024; and OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32, P = .011; respectively). These associations remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, ABO blood group, and location at randomization (Table 4). Considering transfusion of older RBCs, there was no significant increase in 28-day mortality in patients allocated to the older group who were received transfusion with 1 RBC units with storage age of >35 days (n = 3076) and ≥2 RBC units with storage age of >35 days (n = 2432) compared with all patients allocated to the fresh group (irrespective of the age of RBCs received; adjusted OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.88-1.17; P = .753; and adjusted OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.88-1.19; P = .737).

Plots to visually explore potential nonlinear relationships between RBC age and mortality are shown in Figure 6.

Relationship between mean age of RBCs and predicted 28-day mortality.

Discussion

In this IPDMA of the 4 largest multicenter RCTs evaluating storage age of transfused RBCs, we found no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of 28-day mortality between adults allocated to fresh as compared with older RBC transfusion. Pooling individual patient data allowed us to evaluate major subgroups and the effects of receiving RBCs at the extremes of storage age. We found no difference in major patient subgroups, including by underlying diagnosis type (medical vs surgical, cardiac surgery) or comorbidities (stroke, diabetes, renal replacement therapy). In subgroup analysis by country of treatment, although there was no overall evidence of heterogeneity, of the 3 largest countries, we observed an increase in mortality in the fresh group compared with older group in Canada and Australia but not in participants from the United States. Finally, when examining effect of transfusion of RBCs at the extreme of storage age, we found an association between transfusion of RBCs with storage age of ≤7 days, but not >35 days, with increased mortality.

The overall relative effect from receiving fresher RBCs lay between a 2% decrease and a 14% increase in mortality. Our findings strengthen inferences from the 4 large trials, which individually found no overall benefit from transfusion of fresher compared with older RBCs in adult patients. In contrast, our results, if anything, indicate that fresher RBCs may be associated with worse outcomes. Together, these findings suggest that blood services may continue to manage their inventory as per current policies, which is to issue the oldest available RBC unit.

In subgroup analysis by country of treatment, we observed an increase in mortality in the fresh group compared with the older group in Canada and Australia (with very similar effect estimates) but not in participants from the United States. Possible mechanisms that could modify the effect of fresher RBCs compared with older RBCs on mortality between countries include differences in RBC additive solutions and manufacturing processes. For example, both Canada and Australia manufacture RBCs using a buffy coat method, whereas the blood services at participating sites in the United States did not use this method. Other differences between countries include red cell additive solutions. RBC manufacturing methods, which differ in temperature storage after collection and timing of leucodepletion, and different additive solutions, have been linked with differences in RBC characteristics and immunomodulatory activities.27-29 For example, manufacturing methods have been shown to affect presence of extravascular vesicles, which are associated with different immunomodulatory effects of the supernatants in the RBC unit.

In an analysis to explore the effects of transfusion of RBCs at the extremes of storage age, we found an association between transfusion of RBCs with storage age of ≤7 days, but not >35 days, with increased mortality. The biological basis for a possible link between transfusion of fresher RBCs and mortality is not clear and remains hypothetical. In previous meta-analysis of RCTs, transfusion of fresher RBCs was found to be associated with increased risk of infections,5 which could contribute to morbidity and mortality. Some observational studies have also reported associations with worse outcomes with fresher RBCs in different clinical contexts. For example, a recent study in renal transplant recipients found an association between fresher RBCs and worse transplant survival.30 The authors postulated that longer stored RBCs may have immunomodulatory properties that would favorably influence graft survival. It should be noted that our analysis, although analyzed according to treatment allocation, included a subset of participants defined by information available after randomization, and the results should therefore be considered as exploratory only.

Strengths

We followed a prespecified analysis plan and reported our findings according to PRISMA individual patient data. We were able to obtain individual data from 4 of the largest randomized trials conducted, which included >95% of patients enrolled in all studies identified in previous meta-analysis.5 Analysis of individual patient data allowed us to standardize analyses and evaluate key subgroups.

Limitations

Small differences in trial design, interventions, and outcomes may have decreased our ability to find true differences in clinical consequences of fresher RBCs. The definition of “fresh” and “older” RBCs was determined by the trial design of the 4 trials. There were no data on blood donor characteristics or individual product characteristics (eg, type of additive solution) available to include in our analysis. We were unable to analyze other important clinical outcomes, including infection and organ failure. It is plausible that age of red cells may have adverse effects on these outcomes, which is not captured in our IPDMA. Our multivariable models were adjusted for variables common to the 4 trials but may not have included all important parameters that may have resulted in unmeasured confounding. In our updated search, we identified only 1 new study published after our cutoff date that met our inclusion criteria.24 This was a single-center trial in 1387 adults undergoing cardiac surgery comparing transfusion of RBCs stored for ≤14 days vs ≥20 days. The trial was stopped early due to enrollment constraints and reported no difference in the primary end point of morbidity and mortality (16/701 vs 24/686; OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.5-1.2). It is unlikely that inclusion of this trial would have substantially affected our results.

We believe, with our findings, future large trials to address consequences of storage age of RBC transfusion on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients are unlikely to be performed. However, given the evolving understanding of metabolic alterations during RBC storage and novel RBC storage methods,31 further research in potentially high-risk subgroups may be warranted. Furthermore, future studies should also focus on patient populations who receive, or for whom some clinicians preferentially request, fresher RBC units as current standard care, such as patients who have experienced trauma and pediatric recipients of cardiac surgery.

Conclusions

We found no survival benefit from transfusing hospitalized adults with fresher compared with older RBC units. There was sufficient evidence to raise concerns, notably in 2 countries, but an insufficient amount to conclusively infer that RBCs stored for ≤7 days were harmful to patients. Our findings support current blood inventory management policies and are applicable to most hospitalized adults who would not have been excluded from the 4 trials. Based on our results, clinicians should not request fresher RBCs for most hospitalized adults who require RBC transfusion.

Acknowledgments

Susan F. Assmann died before submission of this manuscript (2022); the authors acknowledge her critical contributions to the concept, design, funding, and conduct of the study. The authors thank Richard J. Cook for contributions to the planning of this study and advice regarding statistical analysis.

This study was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1R21HL145377-01). Z.M. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leaders fellowship (GNT1194811) and D.J.C. by a leadership fellowship (GNT2016324). The project was also supported by the NHMRC-funded Blood Synergy program (GNT1189490).

Authorship

Contribution: M.E.S., Z.M., P.H., N.M.H., S.J.S., D.T., J.L., L.v.d.W., C.F., D.A.F., J.E., A.N., M.T., and D.J.C. conceived and designed the study; M.E.S., Z.M., P.H., N.M.H., J.L., and D.J.C. provided the individual trial data; Z.M. and A.S.N. collated and analyzed the data; Z.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Zoe McQuilten, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, 553 St Kilda Rd, Melbourne 3004, Australia; email: zoe.mcquilten@monash.edu.

References

Author notes

Z.M. and M.E.S. contributed equally to this study as joint first authors.

Individual data have not been deposited to a publicly accessible database. For inquiries regarding original data, please contact the corresponding author, Zoe McQuilten (zoe.mcquilten@monash.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.