Key Points

Fitusiran prophylaxis maintained long-term bleeding control in participants with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors.

Fitusiran was associated with an improved safety profile on an AT-based dose regimen, compared with the original dose regimen.

Visual Abstract

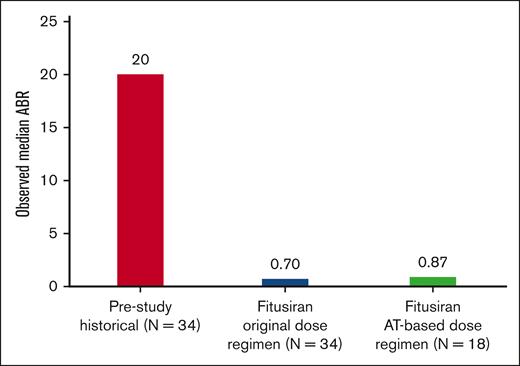

Fitusiran is an investigational small interfering RNA therapeutic that targets antithrombin (AT) to rebalance hemostasis in people with hemophilia. Here, we present the results of a completed phase 2 open-label extension study, which evaluated the long-term safety and efficacy of fitusiran in participants with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors. Male participants who had completed the phase 1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02035605) were enrolled. Participants received monthly subcutaneous fitusiran (50 or 80 mg) under the original dose regimen until a voluntary dosing pause in 2020, after which the AT-based dose regimen was introduced, targeting the recommended AT activity levels of 15% to 35%. Thirty-four participants (hemophilia A, n = 27; hemophilia B, n = 7) were enrolled in the phase 2 study and treated with fitusiran for a median exposure of 4.1 years. Adverse events reported on the original and the AT-based dose regimen were consistent with the identified risks of fitusiran. After implementation of the AT-based dose regimen, there were no thrombotic events, and a reduction in the incidence of elevated transaminases and biliary events was reported. The observed median annualized bleed rate (ABR) on the AT-based dose regimen (0.87) was comparable with the ABR under the original dose regimen (0.70). Furthermore, fitusiran prophylaxis was associated with improved health-related quality of life compared with baseline and provided successful hemostatic control during surgical procedures and invasive interventions. Overall, fitusiran was well tolerated, and effective bleeding control was maintained on an AT-based dose regimen. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02554773.

Introduction

Bleeding in hemophilia A and B is the result of deficiencies of factor VIII (FVIII) and FIX, respectively, leading to insufficient thrombin generation (TG) and disrupted hemostasis.1-3 Treatment strategies for restoring TG to achieve hemostasis in people with hemophilia currently rely on replacing or mimicking the deficient factor.4,5 Prophylaxis is recommended as the standard of care for those with a severe bleeding phenotype6; and until recently, the mainstay prophylactic therapy for people with hemophilia has been to replace the deficient factor with clotting factor concentrates (CFCs) or to treat with bypassing agents (BPAs), that is, when inhibitors are present.6-8

Nonfactor therapies are being developed as alternative therapeutic agents that are not neutralized by anti-factor inhibitors.9 Emicizumab, the first approved agent in this class, is a bispecific monoclonal antibody administered by subcutaneous (SC) injection, which mimics the action of activated FVIII.10-15 It has been approved for routine prophylaxis of bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia A, with or without inhibitors.10,11 Rebalancing agents aim to increase TG by inhibition of naturally occurring anticoagulants (such as antithrombin [AT], tissue factor pathway inhibitor [TFPI], and activated protein C).14-18 Concizumab, a monoclonal antibody against tissue factor pathway inhibitor, was first approved in Canada in 2023 for the treatment of hemophilia B with inhibitors.19 Gene therapy products have also been recently approved (ie, valoctocogene roxaparvovec and etranacogene dezaparvovec), which aim to treat or prevent bleeds in hemophilia A or B by enabling long-term expression through the incorporation of a functioning gene (FVIII or FIX) at therapeutic levels.20,21

Fitusiran is an investigational, SC prophylactic small interfering RNA (siRNA) therapeutic, which lowers AT activity levels and aims to increase TG, with the goal of rebalancing hemostasis in people with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors.15,22 Preclinical data, results from a randomized controlled phase 1 clinical study, and 3 completed phase 3 studies demonstrated dose-dependent AT lowering and increased TG, resulting in improved bleed control in patients who received fitusiran.15,22-28

This manuscript reports the results of the fitusiran phase 2 open-label extension (OLE) study, which was designed to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of fitusiran in male participants with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors, who tolerated and completed fitusiran treatment in the phase 1 study.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This phase 1/2 multicenter, multinational, nonrandomized, long-term, OLE study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02554773) was initiated in September 2015 and completed in March 2023. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and consensus ethical principles derived from international guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legally authorized representatives before enrollment in the study.

Participants who had previously completed the phase 1 multiple ascending dose study and received ≥1 SC dose of fitusiran, ranging from 0.225 mg/kg to 1.8 mg/kg or 50 mg or 80 mg fixed doses, were enrolled (supplemental Figure 1). All participants were transitioned to either 50 mg or 80 mg monthly SC fitusiran after no more than 4 monthly doses in this study.

The study was placed on hold on 01 September 2017 after a fatal event confirmed as an intracranial hemorrhage due to a cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), adjudicated by an independent neuroradiologic review of imaging. The event was initially misdiagnosed as a subarachnoid (primary cerebral) hemorrhage and treated with high doses (ie, >30 IU/kg) of FVIII concentrate, which exceeded the permitted dose of ≤30 IU/kg FVIII that was recommended per protocol at the time and was repeatedly administered over a course of days to weeks. As a result of this event, risk mitigation measures were introduced, including the recommendations for the management of thrombotic events, revised recommendations for the management of sepsis, and additional exploratory laboratory assessments. Furthermore, the breakthrough bleed management guidelines were updated, with recommendations for the use of a lower dose and frequency of CFCs/BPAs than previously allowed (supplemental Table 1). The study was restarted in December 2017, and dosing subsequently resumed.

A voluntary dosing pause was implemented on 30 October 2020 due to nonfatal thrombotic events observed in other clinical studies within the fitusiran clinical program.29 A thorough evaluation of the thrombotic events was conducted, which showed the incident rate of vascular thrombotic events per 100 patient-years in AT categories <10%, 10% to 20%, and >20% was 5.9, 1.5, and 0, respectively, suggesting that very low (<10%) AT activity levels were associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events.29 This led to the introduction of a modified dose regimen, on 25 November 2020, as a risk mitigation measure for thrombotic events, which targeted the recommended AT activity levels of 15% to 35%. A reduced dose of 50 mg administered SC every second month was selected to minimize the occurrence of AT activity levels <10%.29 At a reduced dose of 50 mg every second month, if a participant had >1 AT activity level <15%, the participant was required to permanently discontinue fitusiran. Participants previously exposed to fitusiran at a monthly dose of 50 mg or 80 mg with no more than 1 AT activity level <15% at any time during fitusiran treatment had the option to remain on either dose, respectively (supplemental Figure 2). This modified dose regimen is hereafter referred to as the “AT-based dose regimen.”

Eligible participants were males aged ≥18 years with moderate or severe, clinically stable, hemophilia A or B as evidenced by a laboratory FVIII or FIX level ≤5% at screening or based on a historic laboratory report, who had tolerated fitusiran dosing and completed the phase 1 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02035605). Exclusion criteria included liver disease, known HIV, and history of venous thromboembolism. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the supplemental Appendix.

Study assessments and measurements

Baseline demographic characteristics were assessed at the time of enrollment in the parent study. The primary objective was to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of fitusiran in male participants with moderate or severe hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors. Safety assessments included reported treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs; TEAEs), serious AEs, and AEs of special interest including thromboembolic events, transaminase elevations (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] and/or aspartate transaminase [AST] >3 times upper limit of normal [ULN]), and cholelithiasis/cholestasis; and clinical laboratory evaluations including antidrug antibodies (ADAs).

Secondary objectives were to investigate the long-term efficacy of fitusiran by assessing annualized bleed rate (ABR), spontaneous ABR, and joint ABR during the efficacy period; to characterize AT reduction and TG increase by measuring AT activity levels and TG over time; to characterize the pharmacokinetics of fitusiran (using plasma and urine samples); and to assess changes in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) over time using EuroQoL 5-dimensional questionnaire 5-level and haemophilia quality of life questionnaire (Haem-A-QoL) total score and domain scores. HRQoL scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating improvements in QoL. Further details of HRQoL scores are provided in the supplemental Appendix.

The exploratory objective of this study was to assess the safety and hemostatic efficacy rating for operative procedures performed while on study, based on the hemostatic rating scale adapted from International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Scientific and Standardization Committee definitions.30 The hemostatic efficacy assessment was conducted using a perioperative questionnaire completed by the investigator on the day of the procedure and on postoperative visits 1 and 2. The hemostatic efficacy rating scale for major operative procedures (supplemental Table 2) and the definition of major surgery are included in the supplemental Appendix.

Statistical analysis

All measures of safety and efficacy included in the analysis were summarized using descriptive statistics. Estimates of ABR were calculated as the number of bleed events occurring after the first significant dose (defined as a single dose of fitusiran ≥20 mg) in the parent study or this study and until the end of study visit. The historical ABR was based on 6-month bleed history before the parent study entry. Definitions of the analysis periods can be found in the supplemental Appendix.

Both efficacy and safety analyses under the original and AT-based dose regimens were performed separately, unless otherwise specified. Before the voluntary dosing pause, the analysis period for efficacy end points started from the date of the first significant dose up to the earlier of the 2020 voluntary dosing pause date or the last day of study follow-up. For participants under the AT-based dose regimen, both efficacy and safety data were analyzed from the dose restart day 1 up until the last day of study follow-up. Details of the analysis sets can be found in the supplemental Appendix.

Results

Baseline demographics and patient disposition

For participants under the original dose regimen, safety analysis set 1, the median age was 36.5 years, and all were aged <65 years. For participants under the AT-based dosing regimen, safety analysis set 2, the median age was 36.0 years. The majority of participants in safety analysis set 1 and safety analysis set 2 were White (97.1% and 100% of participants, respectively) and were from Europe (94.1% and 88.9%, respectively; Table 1).

Demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline

| Original dose regimen . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Inhibitor (n = 15) . | Noninhibitor (n = 19) . | Overall (N = 34) . | ||||||

| Hemophilia A (n = 13) . | Hemophilia B (n = 2) . | Total (n = 15) . | Hemophilia A (n = 14) . | Hemophilia B (n = 5) . | Total (n = 19) . | Hemophilia A (n = 27) . | Hemophilia B (n = 7) . | Total (n = 34) . | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 34.0 (6.9) | 25.0 (2.8) | 32.8 (7.2) | 40.6 (12.8) | 36.6 (10.9) | 39.6 (12.2) | 37.4 (10.8) | 33.3 (10.6) | 36.6 (10.7) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 74.9 (15.1) | 85.7 (6.5) | 76.3 (14.6) | 77.1 (10.0) | 74.1 (14.2) | 76.4 (10.9) | 76.1 (12.5) | 77.4 (13.2) | 76.3 (12.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||

| Caucasian/White | 13 (100) | 2 (100) | 15 (100) | 13 (92.9) | 5 (100) | 18 (94.7) | 26 (96.3) | 7 (100) | 33 (97.1) |

| Asian/Oriental | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 1 (2.9) |

| Region, n (%) | |||||||||

| North America | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.9) |

| Europe | 13 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 14 (93.3) | 13 (92.9) | 5 (100) | 18 (94.7) | 26 (96.3) | 6 (85.7) | 32 (94.1) |

| Moderate FVIII or FIX (1%-5%), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (8.8) |

| Severe FVIII or FIX (<1%), n (%) | 13 (100) | 2 (100) | 15 (100) | 13 (92.9) | 3 (60.0) | 16 (84.2) | 26 (96.3) | 5 (71.4) | 31 (91.2) |

| Historic ABR at parent study entry, median (Q1; Q3) | 40.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 40.0 (26.0; 54.0) | 40.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 7.0 (0.0; 24.0) | 4.0 (4.0; 6.0) | 4.0 (0.0; 22.0) | 20.0 (4.0; 40.0) | 6.0 (4.0; 26.0) | 20.0 (4.0; 38.0) |

| History of hepatitis C, n (%) | 11 (84.6) | 0 | 11 (73.3) | 12 (85.7) | 3 (60.0) | 15 (78.9) | 23 (85.2) | 3 (42.9) | 26 (76.5) |

| Exposure, median (Q1; Q3), d∗ | 1054.0 (359.0; 1138.0) | 1271.0 (1101.0; 1441.0) | 1101.0 (359.0; 1258.0) | 1265.5 (479.0; 1534.0) | 1382.0 (1128.0; 1556.0) | 1382.0 (479.0; 1555.0) | 1133.0 (359.0; 1415.0) | 1382.0 (1101.0; 1556.0) | 1135.0 (479.0; 1441.0) |

| AT-based dose regimen | |||||||||

| Inhibitor (n = 8) | Noninhibitor (n = 10) | Overall (N = 18) | |||||||

| Hemophilia A (n = 6) | Hemophilia B (n = 2) | Total (n = 8) | Hemophilia A (n = 6) | Hemophilia B (n = 4) | Total (n = 10) | Hemophilia A (n = 12) | Hemophilia B (n = 6) | Total (n = 18) | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 35.2 (4.6) | 25.0 (2.8) | 32.6 (6.2) | 46.7 (17.9) | 35.8 (12.4) | 42.3 (16.2) | 40.9 (13.8) | 32.2 (11.2) | 38.0 (13.4) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 85.8 (14.2) | 96.5 (4.6) | 88.5 (13.1) | 78.0 (13.2) | 79.4 (16.2) | 78.5 (13.6) | 81.9 (13.7) | 85.1 (15.5) | 82.9 (13.9) |

| Moderate (1%-5%), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (16.7) |

| Race, Caucasian/White, n (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (100) | 8 (100) | 6 (100) | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 18 (100) |

| Region, n (%) | |||||||||

| North America | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (11.1) |

| Europe | 6 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (100) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) | 5 (83.3) | 16 (88.9) |

| Severe FVIII or FIX (<1%), n (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (100) | 8 (100) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) | 11 (91.7) | 4 (66.70) | 15 (83.3) |

| Historic ABR at parent study entry, median (Q1; Q3) | 34.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 40.0 (26.0; 54.0) | 37.0 (20.0; 51.0) | 1.0 (0.0; 24.0) | 4.0 (2.0; 5.0) | 3.0 (0.0; 6.0) | 20.0 (1.0; 43.0) | 5.0 (4.0; 26.0) | 18.0 (2.0; 38.0) |

| History of hepatitis C, n (%) | 6 (100) | 0 | 6 (75.0) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) | 11 (91.7) | 2 (33.3) | 13 (72.2) |

| Exposure, median (Q1; Q3), d† | 546.5 (298.0; 615.0) | 471.0 (400.0; 542.0) | 525.0 (349.0; 600.0) | 574.5 (559.0; 594.0) | 570.5 (397.5; 596.0) | 570.5 (559.0; 594.0) | 574.5 (432.5; 603.5) | 555.0 (400.0; 573.0) | 568.0 (400.0; 594.0) |

| Original dose regimen . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Inhibitor (n = 15) . | Noninhibitor (n = 19) . | Overall (N = 34) . | ||||||

| Hemophilia A (n = 13) . | Hemophilia B (n = 2) . | Total (n = 15) . | Hemophilia A (n = 14) . | Hemophilia B (n = 5) . | Total (n = 19) . | Hemophilia A (n = 27) . | Hemophilia B (n = 7) . | Total (n = 34) . | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 34.0 (6.9) | 25.0 (2.8) | 32.8 (7.2) | 40.6 (12.8) | 36.6 (10.9) | 39.6 (12.2) | 37.4 (10.8) | 33.3 (10.6) | 36.6 (10.7) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 74.9 (15.1) | 85.7 (6.5) | 76.3 (14.6) | 77.1 (10.0) | 74.1 (14.2) | 76.4 (10.9) | 76.1 (12.5) | 77.4 (13.2) | 76.3 (12.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||

| Caucasian/White | 13 (100) | 2 (100) | 15 (100) | 13 (92.9) | 5 (100) | 18 (94.7) | 26 (96.3) | 7 (100) | 33 (97.1) |

| Asian/Oriental | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 1 (2.9) |

| Region, n (%) | |||||||||

| North America | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.9) |

| Europe | 13 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 14 (93.3) | 13 (92.9) | 5 (100) | 18 (94.7) | 26 (96.3) | 6 (85.7) | 32 (94.1) |

| Moderate FVIII or FIX (1%-5%), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (8.8) |

| Severe FVIII or FIX (<1%), n (%) | 13 (100) | 2 (100) | 15 (100) | 13 (92.9) | 3 (60.0) | 16 (84.2) | 26 (96.3) | 5 (71.4) | 31 (91.2) |

| Historic ABR at parent study entry, median (Q1; Q3) | 40.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 40.0 (26.0; 54.0) | 40.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 7.0 (0.0; 24.0) | 4.0 (4.0; 6.0) | 4.0 (0.0; 22.0) | 20.0 (4.0; 40.0) | 6.0 (4.0; 26.0) | 20.0 (4.0; 38.0) |

| History of hepatitis C, n (%) | 11 (84.6) | 0 | 11 (73.3) | 12 (85.7) | 3 (60.0) | 15 (78.9) | 23 (85.2) | 3 (42.9) | 26 (76.5) |

| Exposure, median (Q1; Q3), d∗ | 1054.0 (359.0; 1138.0) | 1271.0 (1101.0; 1441.0) | 1101.0 (359.0; 1258.0) | 1265.5 (479.0; 1534.0) | 1382.0 (1128.0; 1556.0) | 1382.0 (479.0; 1555.0) | 1133.0 (359.0; 1415.0) | 1382.0 (1101.0; 1556.0) | 1135.0 (479.0; 1441.0) |

| AT-based dose regimen | |||||||||

| Inhibitor (n = 8) | Noninhibitor (n = 10) | Overall (N = 18) | |||||||

| Hemophilia A (n = 6) | Hemophilia B (n = 2) | Total (n = 8) | Hemophilia A (n = 6) | Hemophilia B (n = 4) | Total (n = 10) | Hemophilia A (n = 12) | Hemophilia B (n = 6) | Total (n = 18) | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 35.2 (4.6) | 25.0 (2.8) | 32.6 (6.2) | 46.7 (17.9) | 35.8 (12.4) | 42.3 (16.2) | 40.9 (13.8) | 32.2 (11.2) | 38.0 (13.4) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 85.8 (14.2) | 96.5 (4.6) | 88.5 (13.1) | 78.0 (13.2) | 79.4 (16.2) | 78.5 (13.6) | 81.9 (13.7) | 85.1 (15.5) | 82.9 (13.9) |

| Moderate (1%-5%), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (16.7) |

| Race, Caucasian/White, n (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (100) | 8 (100) | 6 (100) | 4 (100) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) | 6 (100) | 18 (100) |

| Region, n (%) | |||||||||

| North America | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (11.1) |

| Europe | 6 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (100) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) | 5 (83.3) | 16 (88.9) |

| Severe FVIII or FIX (<1%), n (%) | 6 (100) | 2 (100) | 8 (100) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) | 11 (91.7) | 4 (66.70) | 15 (83.3) |

| Historic ABR at parent study entry, median (Q1; Q3) | 34.0 (20.0; 48.0) | 40.0 (26.0; 54.0) | 37.0 (20.0; 51.0) | 1.0 (0.0; 24.0) | 4.0 (2.0; 5.0) | 3.0 (0.0; 6.0) | 20.0 (1.0; 43.0) | 5.0 (4.0; 26.0) | 18.0 (2.0; 38.0) |

| History of hepatitis C, n (%) | 6 (100) | 0 | 6 (75.0) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) | 11 (91.7) | 2 (33.3) | 13 (72.2) |

| Exposure, median (Q1; Q3), d† | 546.5 (298.0; 615.0) | 471.0 (400.0; 542.0) | 525.0 (349.0; 600.0) | 574.5 (559.0; 594.0) | 570.5 (397.5; 596.0) | 570.5 (559.0; 594.0) | 574.5 (432.5; 603.5) | 555.0 (400.0; 573.0) | 568.0 (400.0; 594.0) |

If Q2M regimen was administrated for the last recommended dose, duration of treatment exposure in days = (date of last dose of study drug under the AT-based dose regimen – date of first dose of study drug under the AT-based dose regimen) + 56. If QM regimen was administrated for the last recommended dose, duration of treatment exposure (days) = (date of last dose of study drug under the AT-based dose regimen – date of first dose of study drug under the AT-based dose regimen) + 28.

Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3; QM, once monthly; Q2M, every second month.

Duration of treatment exposure (days) = (date of last dose of study drug under the original dose regimen – date of first dose of study drug in LTE14762 study) + 28, excluding the 2 dose suspensions in LTE14762.

Participants exposed to ≥1 doses under the AT-based dose regimen were summarized.

In safety analysis set 1 (original dose regimen), 31 participants (91.2%) had severe hemophilia at study entry, 26 (76.5%) had a history of hepatitis C, and the median historical ABR was 20 (minimum, 0; maximum, 80). In safety analysis set 2 (AT-based dose regimen), 15 participants (83.3%) had severe hemophilia at study entry, 13 participants (72.2%) had a history of hepatitis C, and the median historical ABR was 18 (minimum, 0; maximum, 80).

Of the 34 participants enrolled in the study (supplemental Figure 3), 34 received ≥1 fitusiran dose (50 mg or 80 mg) since the first dose in the treatment period under the original dose regimen, with a median duration of fitusiran treatment exposure of 1135.0 days (3.1 years; Table 1). Eighteen participants received ≥1 dose under the AT-based dose regimen (supplemental Figure 3), with a median duration of fitusiran treatment exposure of 568.0 days (1.6 years; Table 1). Overall, 34 participants initiated the original dose regimen, 18 restarted the study with the AT-based dose regimen, and 12 completed the study, with an overall median duration of fitusiran treatment exposure of 1584.0 days (4.1 years) from the first significant dose in the treatment period until the end of the study.

Safety

In safety analysis set 1 (original dose regimen), 33 of 34 participants (97.1%) experienced ≥1 TEAE (Table 2). The most common TEAEs included ALT increase (n = 10 participants [29.4%]), headache (n = 9 [26.5%]), arthralgia (n = 8 [23.5%]), injection site erythema (n = 7 [20.6%]), and nasopharyngitis (n = 7 [20.6%]). Treatment-emergent serious AEs (TESAEs) were reported in 13 participants (38.2%) in safety analysis set 1. The most common TESAE was cholecystitis in 2 participants (5.9%). Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis were regarded as TEAEs of special interest; and overall, in the original dose regimen period, 4 participants (11.8%) reported cholecystitis and cholelithiasis (each 2 participants [5.9%]).

AEs

| Original dose regimen . | Overall (N = 34) . |

|---|---|

| TEAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TEAE | 33 (97.1) |

| Leading to study discontinuation∗ | 5 (14.7) |

| Leading to study withdrawal† | 3 (8.8) |

| Most common TEAEs, n (%) | |

| ALT increased | 10 (29.4) |

| Headache | 9 (26.5) |

| Arthralgia | 8 (23.5) |

| Injection site erythema | 7 (20.6) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (20.6) |

| Back pain | 6 (17.6) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (17.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (17.6) |

| Transaminase increased | 6 (17.6) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (11.8) |

| Cough | 4 (11.8) |

| Gastrointestinal reflux disease | 4 (11.8) |

| Vomiting | 4 (11.8) |

| Influenza-like illness | 4 (11.8) |

| Pain in extremity | 4 (11.8) |

| TESAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TESAE | 13 (38.2) |

| Leading to study withdrawal‡ | 1 (2.9) |

| Most common TESAE, cholecystitis, n (%) | 2 (5.9) |

| AT-based dose regimen | Overall (N = 18) |

| TEAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TEAE | 14 (77.8) |

| Leading to study discontinuation§ | 1 (5.6) |

| Leading to study withdrawal|| | 1 (5.6) |

| Most common TEAEs, n (%) | |

| COVID-19 | 2 (11.1) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (11.1) |

| TESAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TESAE | 1 (5.6) |

| Leading to study withdrawal¶ | 1 (5.6) |

| Most common TESAE, hepatocellular carcinoma, n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

| Original dose regimen . | Overall (N = 34) . |

|---|---|

| TEAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TEAE | 33 (97.1) |

| Leading to study discontinuation∗ | 5 (14.7) |

| Leading to study withdrawal† | 3 (8.8) |

| Most common TEAEs, n (%) | |

| ALT increased | 10 (29.4) |

| Headache | 9 (26.5) |

| Arthralgia | 8 (23.5) |

| Injection site erythema | 7 (20.6) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (20.6) |

| Back pain | 6 (17.6) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (17.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 (17.6) |

| Transaminase increased | 6 (17.6) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (11.8) |

| Cough | 4 (11.8) |

| Gastrointestinal reflux disease | 4 (11.8) |

| Vomiting | 4 (11.8) |

| Influenza-like illness | 4 (11.8) |

| Pain in extremity | 4 (11.8) |

| TESAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TESAE | 13 (38.2) |

| Leading to study withdrawal‡ | 1 (2.9) |

| Most common TESAE, cholecystitis, n (%) | 2 (5.9) |

| AT-based dose regimen | Overall (N = 18) |

| TEAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TEAE | 14 (77.8) |

| Leading to study discontinuation§ | 1 (5.6) |

| Leading to study withdrawal|| | 1 (5.6) |

| Most common TEAEs, n (%) | |

| COVID-19 | 2 (11.1) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (11.1) |

| TESAE, n (%) | |

| At least 1 TESAE | 1 (5.6) |

| Leading to study withdrawal¶ | 1 (5.6) |

| Most common TESAE, hepatocellular carcinoma, n (%) | 1 (5.6) |

AEs leading to study drug discontinuation included dyspnea (n = 1), transaminases increased (n = 2), atrial thrombosis (n = 1), and CVST (initially misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage, [n = 1]).

AEs leading to study withdrawal included CVST (initially misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage, [n = 1]), dyspnea (n = 1), and transaminase increased (n = 1).

Serious AE leading to study withdrawal was CVST (initially misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage).

AE leading to study drug discontinuation was hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1).

AE leading to study withdrawal was hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1).

Serious AE leading to study withdrawal was hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1).

Five TEAEs in 5 participants (14.7%) were reported to result in discontinuation of the study drug and included dyspnea, 2 events of transaminases increased, atrial thrombosis, and CVST (initially misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage; Table 2). The events of dyspnea, transaminases increased, and CVST led to study withdrawal in 3 participants (8.8%).

The TEAEs of atrial thrombosis and transaminases increased were assessed by the investigator as serious and related to fitusiran; the TEAEs of dyspnea and ALT increased were categorized as nonserious but related to fitusiran. The TEAE of CVST, initially misdiagnosed as subarachnoid hemorrhage, was confirmed to be a CVST by an independent adjudication committee, which included 3 neuroradiologists who reviewed the participant’s computed tomography imaging results (Table 3). The CVST, which was misdiagnosed and treated as a subarachnoid hemorrhage, resulted in death, and the event was recategorized from not related to fitusiran to possibly related to fitusiran.

Summary of thrombotic events

| Hemophilia subtype and inhibitor status . | Dosing regimen . | Other treatments . | Last AT activity level before the event . | Medical history . | Thrombotic event . | Description of the event . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient with Hemophilia A without inhibitor | Original dose regimen | Concomitant use of factor concentrate in excess of the current bleed management guidelines | 15.9% | Hepatitis C positive, cholecystitis, and smoking history (10 cigarettes a day). No history of drug or alcohol abuse. The family history included a fatal ICH in a male sibling with hemophilia at the age of 2 months. | CVST occurred in 2017∗ | The participant was initially suspected of having viral meningitis but was subsequently diagnosed with subarachnoid hemorrhage on the basis of CT imaging. The participant’s clinical course deteriorated despite the administration of FVIII concentrate 2-3 times a day and the participant died secondary to cerebral edema. After this event, the participant’s CT scans were reviewed, and it was confirmed that the initiating event was a CVST, not a subarachnoid hemorrhage. As a result, the assessment of causality was changed from not related to possibility related to fitusiran. |

| Patient with hemophilia B with inhibitor | Original dose regimen | Concomitant use of BPA (rFVIIa) in excess of the current bleed management guidelines in fitusiran clinical studies | 11.7% | The participant developed an inhibitor to FIX as an infant with the first few exposures to FIX concentrates. Coincident with the development of the FIX inhibitor the participant manifested with anaphylaxis. He had a prolonged attempt of desensitization to FIX along with immunosuppression, but this culminated in the development of nephrotic syndrome, so this was abandoned. Before the initiation of fitusiran, the participant had almost continuous bleeding into his left elbow and most of the bleeds occurred with the use of an arm sling or splint over weeks at a time despite attempts at intensified dosing and prophylaxis. | Atrial thrombosis detected in 2019 | The participant was evaluated by general surgery due to right lower quadrant discomfort. A CT scan confirmed a right atrial mass. Fitusiran dosing was interrupted, and the patient was started on FXa inhibitors. The mass did not change in size during treatment with anticoagulation and the participant began to bleed again under FXa inhibitors. The participant resumed fitusiran and continued to be dosed at 80 mg QM until the program wide hold in 2020, and restarted under 50 mg Q2M with the AT-based dose regimen. A follow-up echocardiogram showed enlargement of the right atrial mass. The event was assessed by the investigator as related to fitusiran, which was subsequently permanently discontinued. |

| Hemophilia subtype and inhibitor status . | Dosing regimen . | Other treatments . | Last AT activity level before the event . | Medical history . | Thrombotic event . | Description of the event . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient with Hemophilia A without inhibitor | Original dose regimen | Concomitant use of factor concentrate in excess of the current bleed management guidelines | 15.9% | Hepatitis C positive, cholecystitis, and smoking history (10 cigarettes a day). No history of drug or alcohol abuse. The family history included a fatal ICH in a male sibling with hemophilia at the age of 2 months. | CVST occurred in 2017∗ | The participant was initially suspected of having viral meningitis but was subsequently diagnosed with subarachnoid hemorrhage on the basis of CT imaging. The participant’s clinical course deteriorated despite the administration of FVIII concentrate 2-3 times a day and the participant died secondary to cerebral edema. After this event, the participant’s CT scans were reviewed, and it was confirmed that the initiating event was a CVST, not a subarachnoid hemorrhage. As a result, the assessment of causality was changed from not related to possibility related to fitusiran. |

| Patient with hemophilia B with inhibitor | Original dose regimen | Concomitant use of BPA (rFVIIa) in excess of the current bleed management guidelines in fitusiran clinical studies | 11.7% | The participant developed an inhibitor to FIX as an infant with the first few exposures to FIX concentrates. Coincident with the development of the FIX inhibitor the participant manifested with anaphylaxis. He had a prolonged attempt of desensitization to FIX along with immunosuppression, but this culminated in the development of nephrotic syndrome, so this was abandoned. Before the initiation of fitusiran, the participant had almost continuous bleeding into his left elbow and most of the bleeds occurred with the use of an arm sling or splint over weeks at a time despite attempts at intensified dosing and prophylaxis. | Atrial thrombosis detected in 2019 | The participant was evaluated by general surgery due to right lower quadrant discomfort. A CT scan confirmed a right atrial mass. Fitusiran dosing was interrupted, and the patient was started on FXa inhibitors. The mass did not change in size during treatment with anticoagulation and the participant began to bleed again under FXa inhibitors. The participant resumed fitusiran and continued to be dosed at 80 mg QM until the program wide hold in 2020, and restarted under 50 mg Q2M with the AT-based dose regimen. A follow-up echocardiogram showed enlargement of the right atrial mass. The event was assessed by the investigator as related to fitusiran, which was subsequently permanently discontinued. |

CT, computed tomography; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage.

As assessed by an independent adjudication committee including review of the patient’s CT scans by 3 independent neuroradiologists, who all confirmed that the initiating event was a CSVT and not a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

In safety analysis set 2 (AT-based dose regimen), 14 of 18 participants (77.8%) experienced ≥1 TEAE (Table 2). The most common TEAEs were COVID-19 and viral upper respiratory tract infection (both reported in 2 participants [11.1%]). There were no “suspected or confirmed thromboembolic events,” and there were no events of cholecystitis or cholelithiasis reported during the AT-based dose regimen. There was 1 drug discontinuation/withdrawal due to a TESAE of hepatocellular carcinoma (in a participant who had a history of chronic hepatitis C), which was assessed by the investigator as not related to fitusiran.

Six participants (17.6%) with hemophilia A were reported to have “ALT or AST elevations >3× ULN” in safety analysis set 1 (original dose regimen; supplemental Table 3), which were classified by the investigator as nonserious, and the majority were rated as mild or moderate in severity; 4 of 6 participants reported a history of alcohol consumption before the ALT/AST elevations occurred.

One participant (5.6%) was reported to have “ALT or AST elevations >3× ULN” in safety analysis set 2 (AT-based dose regimen; supplemental Table 3). The participant had increased transaminases, which led to study drug discontinuation due to withdrawal of consent. The participant reported a history of alcohol consumption before the occurrence of ALT/AST elevations.

Overall, 2 participants in the original dose regimen period developed ADAs. One participant was ADA positive at month 10 (titer, 200) and ADA negative at subsequent time points (months 13 and 16); the ADA response in this participant was considered transient. The second participant was ADA positive at month 48 in the original dose regimen period (titer, 400) and at months 60 and 72 (titer, 100) in the AT-based dose regimen period but was ADA negative at the end of treatment (month 84). No other participants were ADA positive during the AT-based dose regimen period. No associated safety or efficacy findings were reported in these 2 participants in the ADA positivity window.

Bleeding episodes

Fitusiran prophylaxis maintained effective bleed protection over a 6-year period. The observed median ABR during the efficacy period was 0.70 (quartile 1 [Q1], 0.00; quartile 3 [Q3], 3.97) in the original dose regimen and 0.87 (Q1, 0.00; Q3, 5.36) in the AT-based dose regimen period (Figure 1).

Overall, the spontaneous ABR and joint ABR in the original dose regimen and in the AT-based dose regimen were similar. The median observed spontaneous ABR was 0.33 (Q1, 0.00; Q3, 1.68) in the original dose regimen period and 0.00 (Q1, 0.00; Q3, 3.84) in the AT-based dose regimen period (supplemental Figure 4). The median observed joint ABR was 0.55 (Q1, 0.00; Q3, 2.83) in the original dose regimen period and 0.87 (Q1, 0.00; Q3, 3.84) in the AT-based dose regimen period (supplemental Figure 5).

Assessment of AT activity levels and TG

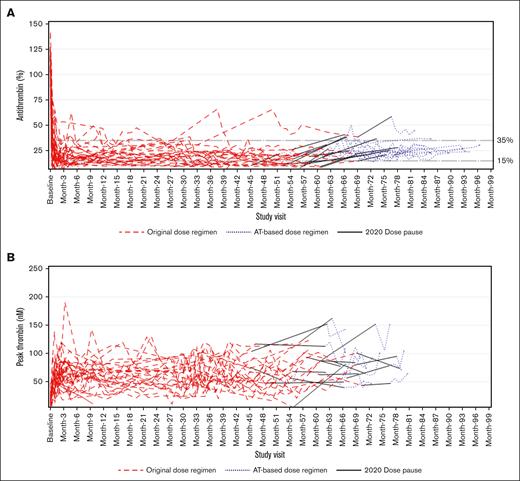

In the original dose regimen period, monthly dosing with fitusiran resulted in sustained lowering of AT activity levels, with a mean reduction of 96% (standard deviation [SD], 12) from baseline to end point (ie, last available assessment before the end of study) and a mean AT percentage change from baseline to end point of –86% (SD, 4) starting at month 1 and persisting over several months. In the AT-based dose regimen, the mean reduction and mean AT percentage change from baseline to end point (ie, last available assessment before end of study) were 82% (SD, 15) and –77% (SD, 9), respectively. There were 3 participants who discontinued the study in the AT-based dose regimen period due to >1 AT activity level <15%. The AT activity levels of the remainder of the participants were maintained between 15% to 35% (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 6).

Assessment of antithrombin (AT) and thrombin activity. (A) Spaghetti plot of AT (%) activity level over time. (B) Spaghetti plot of peak thrombin (nM) over time.

Assessment of antithrombin (AT) and thrombin activity. (A) Spaghetti plot of AT (%) activity level over time. (B) Spaghetti plot of peak thrombin (nM) over time.

Consistent with the mechanism of action of fitusiran, TG increased with AT lowering (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 7), from a mean at baseline of 17 nM (SD, 10) to a peak mean of 74 nM (SD, 27) by end point evaluation (ie, last available assessment under the original dose regimen) that remained elevated during the course of fitusiran treatment for the overall participants in the original dose regimen period (ie, 66 months). In the AT-based dose regimen period, TG increased from a mean at baseline of 15 nM (SD, 6) to a peak mean of 88 nM (SD, 29) by end point evaluation (ie, last available assessment on AT-based dose regimen) for the overall participants, although TG assessments were only included for the first 6 months under the AT-based dose regimen. This was due to an issue with a new batch of trigger reagent used for the TG assay introduced on 06 October 2021, which affected the measurement of TG in participant samples after this date. This meant that samples from 17 participants in the AT-based dose regimen analysis set were excluded from the data analysis. Details of the issue with the trigger reagent can be found in the supplemental Appendix. AT lowering correlated with TG peak increase until the point in which the samples had to be excluded, and no further conclusions could be made.

During the clinical hold in 2017, AT activity levels in patients previously receiving fitusiran progressively increased. The mean AT recovery was >60% at 5 months after dosing interruption (mean, 69% [SD, 17]), with a mean AT recovery of 7% per month over 11 months. Consequently, TG gradually decreased, with a peak mean of 24 nM (SD, 13) by month 5 of the clinical hold.

Patient-reported outcomes

Reductions in Haem-A-QoL “total” and “physical health” scores were observed in 14 of 34 participants in the original dose regimen period and 9 of 18 participants in the AT-based dosing period (Figure 3). The number of participants included in the Haem-QoL analysis represents the participants who had a recorded value at baseline and the respective listed month. Not all participants had a baseline value because Haem-A-QoL was not an end point under the original protocol, and participants only had a baseline value if they rolled over into the phase 2 OLE study after the protocol amendment was implemented. Reductions of 7.1 points in “total” score and 10 points in “physical health” score are regarded as practical thresholds for identifying notable improvements in HRQoL.31 Thus, observed reductions in both the “total” and “physical health” scores under both dose regimens are indicative of HRQoL benefits, with meaningful improvements observed under the AT-based dose regimen.

Change from baseline in Haem-A-QoL domains.∗A reduction of 7.1 points in “total score” is regarded as a clinically meaningful improvement and is depicted by the dashed line.31 †A reduction of 10 points in “physical health” is regarded as a clinically meaningful improvement and is depicted by the dashed line.31 ‡Last non-missing assessment on or before the first significant dose. §Under the original dose regimen the mean change in baseline was through 24 months (n = 14). ǁUnder the AT-based dose regimen the mean change from baseline was through 12 months (n = 9).

Change from baseline in Haem-A-QoL domains.∗A reduction of 7.1 points in “total score” is regarded as a clinically meaningful improvement and is depicted by the dashed line.31 †A reduction of 10 points in “physical health” is regarded as a clinically meaningful improvement and is depicted by the dashed line.31 ‡Last non-missing assessment on or before the first significant dose. §Under the original dose regimen the mean change in baseline was through 24 months (n = 14). ǁUnder the AT-based dose regimen the mean change from baseline was through 12 months (n = 9).

Perioperative management

Six participants receiving the original dose regimen underwent a total of 9 major surgical procedures, and 1 participant receiving the AT-based dose regimen underwent 1 major surgical procedure (Table 4; supplemental Table 4). Fitusiran treatment was paused for 2 of 9 procedures (surgery 1 and 3) under the original dose regimen but was continued for the majority of procedures (7/9 procedures [77.8%] under the original dose regimen; and 1/1 procedure [100%] under the AT-based dose regimen). After major surgery, excellent hemostatic efficacy was reported by the investigator for 5 of 9 procedures (surgeries 1, 2, 6, 7, and 9) in the original dose regimen period and 1 of 1 procedure (surgery 10) in the AT-based dosing period. Hemostatic efficacy was not rated/reported by the investigator for 4 of 9 procedures (surgeries 3-5 and 8) under the original dose regimen, although hemostatic management was successful. No blood components or AT concentrate were given during any of the procedures (although AT concentrate was given 1 day before surgery 10, which was a tooth extraction under the AT-based dose regimen), and blood loss was minimal.

Summary of surgical procedures performed during trial

| Surgery no. . | Hemophilia subtype and inhibitor status . | Fitusiran dosing regimen . | AT activity level on day of or before surgery and timing . | Type of procedure . | Perioperative hemostatic agent(s) used . | Hemostasis efficacy rating∗ . | AEs in perioperative period . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HA | Discontinued before surgery, due to dosing hold | 54.2% (at time of procedure) | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | FVIII | Excellent | CRP increased, LDH increased |

| 2 | HB with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 12.3% (on day of surgery) | Right ankle fusion and Achilles tendon lengthening | rFVIIa | Excellent | None |

| 3 | HA with inhibitors | Paused due to surgery | 17.7% (62 days before surgery) | Left knee total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | Anemia postoperative, blood loss anemia, and post procedural edema |

| 4 | HA with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.0% (1 day before surgery) | Metal plate removal and right hip total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | Mild postoperative hematoma reported 1 day after surgery, which required no treatment; postoperative anemia |

| 5 | HA with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 12.6% (1 day before surgery) | Left knee total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | None |

| 6 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 15.0% (1 day before surgery) | Nasal septoplasty | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 7 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.3% (21 days before surgery) | Endoscopic Cholecystectomy | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 8 | HA | Original dose and regimen ongoing | 15.7% (18 day before surgery) | Extraction of two wisdom teeth | None | Not rated‡ | None |

| 9 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.2% (3 days before surgery) | Bilateral knee replacement | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 10 | HB | AT-based dose regimen ongoing | 12.2% (2 day before surgery) | Tooth extraction | AT III (human) (before surgery) Tranexamic acid (day of procedure) | Excellent | None |

| Surgery no. . | Hemophilia subtype and inhibitor status . | Fitusiran dosing regimen . | AT activity level on day of or before surgery and timing . | Type of procedure . | Perioperative hemostatic agent(s) used . | Hemostasis efficacy rating∗ . | AEs in perioperative period . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HA | Discontinued before surgery, due to dosing hold | 54.2% (at time of procedure) | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | FVIII | Excellent | CRP increased, LDH increased |

| 2 | HB with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 12.3% (on day of surgery) | Right ankle fusion and Achilles tendon lengthening | rFVIIa | Excellent | None |

| 3 | HA with inhibitors | Paused due to surgery | 17.7% (62 days before surgery) | Left knee total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | Anemia postoperative, blood loss anemia, and post procedural edema |

| 4 | HA with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.0% (1 day before surgery) | Metal plate removal and right hip total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | Mild postoperative hematoma reported 1 day after surgery, which required no treatment; postoperative anemia |

| 5 | HA with inhibitors | Original dose regimen ongoing | 12.6% (1 day before surgery) | Left knee total replacement | aPCC | Not reported† | None |

| 6 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 15.0% (1 day before surgery) | Nasal septoplasty | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 7 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.3% (21 days before surgery) | Endoscopic Cholecystectomy | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 8 | HA | Original dose and regimen ongoing | 15.7% (18 day before surgery) | Extraction of two wisdom teeth | None | Not rated‡ | None |

| 9 | HA | Original dose regimen ongoing | 13.2% (3 days before surgery) | Bilateral knee replacement | FVIII | Excellent | None |

| 10 | HB | AT-based dose regimen ongoing | 12.2% (2 day before surgery) | Tooth extraction | AT III (human) (before surgery) Tranexamic acid (day of procedure) | Excellent | None |

Please see supplemental Table 4 in the supplemental Appendix for more detail of the hemostatic efficacy and safety of operative procedures, including a description of the dose and timing of perioperative hemostatic treatment.

aPCC, activated prothrombin complex concentrate; CRP, C-reactive protein; HA, hemophilia A; HB, hemophilia B; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; rFVIIa, activated recombinant FVII.

The hemostatic efficacy rating of the procedure was assessed by the respective investigators.

Although the hemostatic efficacy rating was not reported for these procedures, it was noted by the investigator that each of these procedures were covered by fitusiran alone with the perioperative hemostatic plan using only reduced doses and frequency of aPCC as recommended in the bleed management dosing guidelines in the protocol. None of these procedures required AT reversal, and no excessive bleed occurred during surgeries. Thus, it was concluded that fitusiran in association with reduced dose and frequency of aPCC administered perioperatively demonstrated successful hemostatic management.

The procedure was covered by fitusiran alone without using any FVIII concentrate dose perioperatively. The procedure did not require AT reversal, and no excessive bleed occurred during the surgery. Fitusiran has demonstrated successful hemostatic management without any adjunction of FVIII concentrate perioperatively.

Discussion

Overall, participants were treated with fitusiran for a median exposure of 4.1 years during the study. Risk-mitigation measures including bleed management guidance (using reduced doses and frequency of CFCs/BPAs) as well as a revised dose regimen targeting AT activity levels of 15% to 35% were implemented successfully. Long-term safety and efficacy data are consistent with the findings of parts C and D of the phase 1 study in which participants were exposed to similar doses and regimen of fitusiran as this study, with doses ranging from 0.225 mg/kg to 1.8 mg/kg or 50 mg or 80 mg fixed monthly doses.22,25

Participants with hemophilia treated with fitusiran maintained effective bleed control on the AT-based dose regimen, regardless of hemophilia type and inhibitor status. Fitusiran was well tolerated, and the overall safety profile appeared to be more favorable in participants receiving the AT-based dose regimen relative to the original dose regimen in this small cohort. With the AT-based dose regimen, there were no thrombotic events, and the incidence of elevated transaminases and biliary events was reduced. In addition, ADA data indicate that fitusiran has low potential to elicit an immunogenic response.

Long-term safety assessments conducted during the original dose regimen period and the AT-based dose regimen period showed that the benefit-risk profile of fitusiran during long-term dosing was favorable, and the type and frequency of reported AEs were generally consistent with the identified risks of fitusiran, including events of liver transaminase elevations, thrombosis, cholecystitis, and cholelithiasis.

Two cases of thrombosis occurred over the course of the study. Within the general population, the risk of thrombosis may be increased by exogenous factors, such as surgery or immobilization, or endogenous factors, such as cancer, obesity, or disorders of hypercoagulation.32 In the context of hemophilia treatment and restoring TG, the risk of thrombosis should be a consideration when nonfactor therapies are used concomitantly with other hemostatic agents, such as CFCs/BPAs, to treat bleeding episodes.33 In this study, both thrombotic events occurred under the original dose regimen, and in both cases, the patients were given concomitant CFCs/BPAs in excess of the current bleed management guidelines and had no other thrombotic risk factors. After the introduction of the revised breakthrough bleed management guidelines for fitusiran and the AT-based dose regimen, no additional thrombotic events were reported in this study.

It has been suggested that it may be useful to evaluate patients with hemophilia for thrombophilia before starting nonfactor therapies, to help ascertain the risk of thrombotic events.33 Participants in the fitusiran trials were all screened for known major hereditary thrombophilias including FV Leiden, protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, and prothrombin mutation (G20210A). Patients with a known coexisting thrombophilic disorder were excluded from the trial.

In this study, the majority of elevations in liver enzymes ALT or AST >3× ULN were classified as mild to moderate in severity; they were transient and resolved and were less frequent on the AT-based dose regimen. Similarly, cholecystitis and cholelithiasis were reported in 2 participants each (5.9%) on the original dose regimen but not on the AT-based dose regimen. The mechanism of action of fitusiran relies on targeted delivery of the drug to the liver where AT is synthesized.34 Therefore, occurrence of hepatic AEs is also of particular interest, especially in a population with a high incidence of chronic hepatitis C or prior infection. The underlying pathophysiology for the development of transaminase elevations, cholecystitis, and cholelithiasis is unknown, and these risks remain under investigation in ongoing trials. Transaminase elevations have also been reported with approved siRNA therapies for other indications.35,36 Risk mitigation measures for hepatotoxicity are implemented in ongoing clinical studies and include transaminase monitoring and guidelines for withholding and permanent discontinuation of fitusiran.

Treatment with fitusiran resulted in sustained lowering of AT activity levels and a substantial decrease in observed median ABRs, spontaneous ABRs, and joint ABRs over a 6-year period compared with baseline. Haem-A-QoL assessments taken during the study showed improvements with both the original dose regimen and AT-based dose regimen compared with baseline. This included an improvement in the score for “physical health,” which evaluates painful swelling, joint pain, pain with movement, difficulty walking, and time to get ready, and is regarded as one of the domains that reflect key impairments in QoL.31 Further observations will be made to assess the changes in Haem-A-QoL in ongoing studies.

Successful perioperative hemostatic control while receiving SC fitusiran was observed in 7 of 7 participants (100%) who underwent surgery.

Limitations of this phase 2 study include its open-label design, the small study population, and the absence of a control group. However, extensive long-term exposure to fitusiran was achieved on both original and AT-based dose regimens, with an average of 3 and 1.5 years, respectively. Despite 2 periods in which fitusiran treatment was paused in 2017 and 2020, a substantial number of participants completed the entire study. The limited sample size meant that analyses were sensitive to variability caused by individual participants, and calculated mean was affected by outliers. However, adequate bleed control was maintained on fitusiran prophylaxis, both at the original and AT-based dose regimens throughout 6 years of fitusiran exposure.

Conclusion

Fitusiran, an investigational SC prophylactic siRNA therapeutic, targets AT to rebalance hemostasis in people with hemophilia A or B, with or without inhibitors. In this small cohort, the overall safety profile of fitusiran appeared to be more favorable in participants receiving the AT-based dose regimen relative to the original dose regimen, and effective bleeding control was maintained on the AT-based dose regimen. After the implementation of the AT-based dose regimen, no thrombotic events, no cholecystitis/cholelithiasis, and a reduction in ALT/AST elevations were reported.

The results of this long-term study indicate that fitusiran prophylaxis was effective at reducing AT and restoring sufficient TG to achieve hemostasis and reducing bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia A and B, with and without inhibitors, under both the original and the AT-based dose regimen. HRQoL was improved with fitusiran in the study participants compared with baseline. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that fitusiran was effective in providing successful bleed control during surgical procedures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators, health care providers, research staff, and patients who participated in this fitusiran phase 2 open-label extension study.

Medical writing and editing support were provided by Emily Foster of Lucid Group Communications Ltd, and this support was funded by Sanofi.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors had access to primary clinical trial data, had full editorial control of the manuscript, and provided their final approval of all content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.W.P. has received consultancy fees from ApcinteX, ASC Therapeutics, Bayer, BioMarin, CSL Behring, HEMA Biologics, Freeline, LFB, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Regeneron/Intellia, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Takeda, Spark Therapeutics, and uniQure; has received research funding from Siemens; and holds a membership on a scientific advisory committee for GeneVentiv and Equilibra Bioscience. T.L. is a principal investigator of clinical trials for Bayer, Octapharma, Sanofi-Alnylam, and Sanofi-Bioverativ; has served on advisory boards for Roche and Sobi; and has served as a lecturer for Novo Nordisk, Roche, and Sobi. S.M. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaking, and educational events from Sobi, Roche, and Novo Nordisk; has participated in advisory boards for Takeda, Roche, Chugai Pharmaceutical, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Sobi, and Sanofi; and has received support for attending meetings from Octapharma, Roche, Sobi, and Novo Nordisk. I.H. has received consultancy fees from Bayer, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Roche, Shire/Takeda, Sobi, and UniQure; has received multisponsoring for a hemophilia nurse at the Hemophilia Comprehensive Care Center from Bayer, Biotest, CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Pfizer, Shire/Takeda, and Sobi; and has been an employee of Novo Nordisk since February 2022. A.T. has received advisory fees from Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sobi, and Takeda; financial support for congresses/courses from Novo Nordisk, Takeda, and Sobi; and financial support for hemophilia nurse and physiotherapy activities/projects from CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Roche, and Sobi. P.C. has served on advisory boards for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, ApcinteX, CSL Behring, Chugai, Freeline, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Spark, Sobi, and Takeda, and has received research funding from Bayer, CSL Behring, Freeline, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Takeda, and Sobi. M.V.R. reports research funding to the University of Pittsburgh from BioMarin, Sanofi, SPARK, and Takeda, and serves on advisory boards of BeBio, BioMarin, Hema Biologics, Sanofi, SPARK, and Takeda. L.F., L.A.M., S.K., S.A., and M.D. are Sanofi employees and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company.

Correspondence: Steven W. Pipe, Departments of Pediatrics and Pathology, University of Michigan, 1500 E Medical Center Dr, MPB D4207, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5718; email: ummdswp@med.umich.edu.

References

Author notes

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level data and related study documents, such as the clinical study report, study protocol (with amendments), blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and data set specifications. Of note, patient-level data will be anonymized, and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants. Further information related to Sanofi’s data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at https://vivli.org/.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.