Key Points

Novel insights in NAD+ metabolism of MM overcome the therapeutic limitations of previous NAD+ depletion strategy through NAMPT inhibitors.

Dual NAMPT/NAPRT inhibition compromise oxidative homeostasis, heightening melphalan sensitivity, suggesting a potential combination therapy.

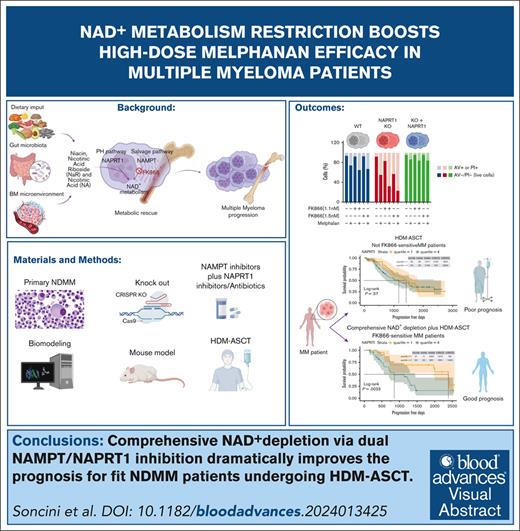

Visual Abstract

Elevated levels of the NAD+-generating enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) are a common feature across numerous cancer types. Accordingly, we previously reported pervasive NAD+ dysregulation in multiple myeloma (MM) cells in association with upregulated NAMPT expression. Unfortunately, albeit being effective in preclinical models of cancer, NAMPT inhibition has proven ineffective in clinical trials because of the existence of alternative NAD+ production routes using NAD+ precursors other than nicotinamide. Here, by leveraging mathematical modeling approaches integrated with transcriptome data, we defined the specific NAD+ landscape of MM cells and established that the Preiss-Handler pathway for NAD+ biosynthesis, which uses nicotinic acid as a precursor, supports NAD+ synthesis in MM cells via its key enzyme nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT). Accordingly, we found that NAPRT confers resistance to NAD+-depleting agents. Transcriptomic, metabolic, and bioenergetic profiling of NAPRT-knockout (KO) MM cells showed these to have weakened endogenous antioxidant defenses, increased propensity to oxidative stress, and enhanced genomic instability. Concomitant NAMPT inhibition further compounded the effects of NAPRT-KO, effectively sensitizing MM cells to the chemotherapeutic drug, melphalan; NAPRT added-back fully rescues these phenotypes. Overall, our results propose comprehensive NAD+ biosynthesis inhibition, through simultaneously targeting NAMPT and NAPRT, as a promising strategy to be tested in randomized clinical trials involving transplant-eligible patients with MM, especially those with more aggressive disease.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an aggressive blood cancer characterized by malignant plasma cell accumulation in the bone marrow (BM), leading to complications like fractures, anemia, infections, and organ damage.1-3 Despite advances in treatment, including monoclonal antibodies, proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), T-cell engagers (TCAs) and chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T), most patients eventually progress.1,4-7 Thus, there remains a crucial need to better identify those factors that are responsible for treatment resistance and thereby design innovative strategies to overcome it. Cancer cells, including MM cells, rely on altered metabolism, such as enhanced glycolysis (Warburg effect), TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, all of which depend on NAD+.8-13 Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme for NAD+ production from nicotinamide (NAM) in mammalian cells, is frequently expressed at high levels in both solid and hematologic cancers, including MM.14-18 Recent studies show that other NAD+-producing enzymes, such as nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT), which is responsible for starting the generation of NAD+ from nicotinic acid (NA), instead of from NAM, is also frequently upregulated in human malignancies.19,20 Similar to NAMPT, NAPRT was also shown to be key in maintaining NAD+ levels in cancer cells, particularly in those cancers arising from tissues in which NAPRT is normally present and active.20 All these data support NAD+ biosynthesis inhibition as an innovative therapeutic strategy for hematologic cancers as well as in several solid tumors.21 NAMPT inhibitors (eg, FK866 and CHS828) have shown promise in preclinical models for MM and other cancers, but their clinical efficacy has been limited because of compensatory NAD+ production mechanisms.15-17,22-26 In order to define the key features and the relevance of the NAD+ metabolism in MM, we comprehensively annotated NAD+-producing enzymes, NAD+ precursors, and metabolites of MM cells. By integrating mathematical modeling with metabolic, bioenergetics, and transcriptome data, we highlight the key role of NAPRT in sustaining NAD+ production, managing oxidative stress, and preventing DNA damage. We also show dual NAMPT/NAPRT targeting to effectively deplete NAD+ levels in MM cells, predisposing them to DNA damage and to cell demise in response to melphalan. Our results lay the background for exploiting NAMPT and NAPRT as therapeutic targets and as biomarkers of chemotherapy efficacy in patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM).

Materials and methods

Cell lines and primary tumor specimens, reagents, and analyses

Details on cell lines, reagents, western blotting, viability assays, drug synergy evaluation, quantitative reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and transcriptome profiling are provided in the supplemental File.

Generation of NAPRT-KO cells

NAPRT knockout (KO) cell lines were developed using the CRISPR-Cas9 system in inducible-SpCas9 KMS11 cells. Six hours before nucleofection, Cas9 expression was induced in KMS11 iCas9 cells with 1 μg/mL doxycycline. Afterward, 2.5 × 106 iCas9 KMS11 cells were nucleofected with 3 μg of human NAPRT-specific guide RNA (TrueGuide, ThermoFisher) using the DA-100 program on the Amaxa SF Cell Line 4-D Nucleofector X kit L (Lonza). Cells were then plated in 96-well plates at 1 cell per well and clonally selected. Single clones were expanded and validated by Sanger sequencing with primers: NAPRT sequence forward 5′-TACTATTAGCCCCACCCGTC-3′ and NAPRT sequence reverse 5′-GGGGACAAGGACTTCCACC-3′. The genetic profiles of KO clones are shown in supplemental Table 1.

NAPRT addback

To generate stable isogenic MM cell lines, NAPRT-overexpressing lentiviral plasmid was transduced into KMS11 NAPRT-KO clones. All lentiviral plasmids were purchased from VectorBuilder GmbH; further details are provided in the supplemental File.

In vivo mouse models

Five-week-old female NOD/SCID J mice (Charles Rivers Laboratories, France) were acclimated for 3 weeks. A total of 4.5 × 106 MM1S shScramble or shNAPRTsh#2 cells were injected subcutaneously into both flanks of each mouse. When tumors reached ∼50 mm³, mice engrafted with the same MM-edited cells were randomly assigned to either the control group (vehicle, dimethyl sulfoxide) or treatment with FK866 (30 mg/kg intraperitoneally, twice daily for 18 days, dissolved in vehicle). Tumor volume was calculated as: tumor volume = (w2 × W) × π/6, in which “w” and “W” represent the minor and major sides in mm, respectively. Mice were euthanized when tumors reached 1.5 cm³, and survival was recorded from the treatment start to euthanasia. All in vivo procedures complied with animal care regulations and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of University Hospital San Martino (protocol number 473).

Quantification of NAD+ metabolites using LC-MS/MS

Extracted samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) as detailed in the work of ElMokh et al.27

Statistical analyses

All experiments were repeated at least twice, with representative results shown in the figures. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons between 2 groups were performed using the Student t test in GraphPad Prism, with significance set at P <.05. Tumor volume was analyzed using a 2-way paired t test, and survival was assessed by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Human samples were collected at the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Policlinico San Martino (Genoa, Italy) in accordance with a protocol approved by the local ethics committee after informed consent has been obtained from each patient (institutional review board Comitato Etico Regionale Liguria 627/2022-DB id 12753). All in vivo experiments were performed in accordance with the laws and institutional guidelines for animal care, approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of University Hospital San Martino (protocol number 473).

Results

NAD+ biosynthesis of MM cells predominantly relies on PH and salvage pathways, and its dysregulation predicts clinical outcomes

Mammalian cells produce NAD+ via 3 pathways: (1) de novo synthesis from tryptophan, (2) via the Preiss-Handler (PH) pathway from NA, and (3) via the salvage pathway from NAM or nicotinamide riboside (NR; supplemental Figure 1).19,28-32 Enzymes like quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase, NAMPT, NAPRT, and nicotinamide mononucleotide kinase 1 and 2 facilitate NAD+ synthesis from these precursors.30 The contribution of each NAD+ pathway depends on factors such as tumor origin, environment, and precursor availability. However, the mechanisms by which tumor cells choose a specific NAD+ production route remain unclear.

Thus, we started our study on the NAD+ biosynthetic landscape of MM cells by analyzing the transcription levels of the abovementioned enzymes in 767 patients with MM included in the IA21 release of the CoMMpass data set and in our independent cohort of 20 patients with NDMM as well. High variability was observed, with enzymes from the salvage and PH pathways exhibiting higher expression compared with others (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry analyses confirmed these also in CD138+ cells of BM biopsies obtained from patients with MM (Figure 1B). Consistent with these observations, genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 data (depmap.org) reveal that NAMPT and NAPRT are the most critical NAD+ biosynthetic enzymes in MM cells, highlighting the combined role of multiple pathways in maintaining NAD+ levels (Figure 1C). These dependencies were also observed in other hematologic malignancies, underscoring the specific relevance of these enzymes in blood cancers over solid tumors (supplemental Figure 2B). To investigate further, we standardized a NADome signature using the CoMMpass data set with a “min-max” method33 classifying patients into low, intermediate, and high NADome groups (Figure 1D). High NADome patients had shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than low-NADome patients (median PFS, 652 vs 970 days; P = .03 and median OS, 1500 days vs not reached; P = .0001; Figure 1E). Multivariate Cox analysis confirmed that NADome signature independently predicted PFS and OS (P = .009 and P < .001), similar to International Staging System stages II and III (both P < .001) and 1q amplification (P = .146 and P = .027; supplemental Figure 3A-B). This analysis linked high NADome dysregulation with more aggressive MM and poorer outcomes. Expanding our study using the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation CoMMpass data set, we observed that amplifications in NAD+-related genes were more frequent than other alterations, with mutations in NAPRT, NAMPT, and QPRT occurring in <1% of samples, but amplifications were common, particularly in the PH and salvage pathway genes (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Using a kinetic model of NAD biosynthesis (NADnet) with transcriptomic data from CoMMpass,33 we confirmed pathway heterogeneity across patients with MM, with the PH pathway as a major NAD+ producer (Figure 1F). The correlation between NAPRT expression and NAD+ levels was the strongest among NAD+ producer genes (Figure 1G). This suggests that dual targeting of the salvage and PH pathways may enhance therapeutic efficacy in MM by achieving more effective NAD+ depletion. Given the strong predictive value of cytogenetic abnormalities for MM outcomes, we focused on the CoMMpass molecular data: NADome signature, NAMPT, and NAPRT expression were significantly upregulated in patients with t(14;16), indicating that targeting NAD+ biosynthesis is a promising therapeutic strategy, particularly for patients with this poor prognosis marker (Figure 1H).34

NAD+ biosynthesis of MM cells predominantly relies on PH and salvage pathways, and its dysregulation predicts the clinical outcome. (A) Box plot of expression levels for indicated NAD+ biosynthetic genes in MM samples included in the CoMMpass study. Red, green, and purple bars represent de novo, PH-, and salvage pathway–related genes, respectively. Orange bars represent genes shared by all the NAD+-generating pathways. The abscissa represents the gene name, whereas the ordinate displays its expression as log10 transcripts per million (TPM). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of a representative BM biopsy collected from patients with NDMM. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), GIEMSA staining, along with CD138, NADSYN, NAPRT, and NAMPT markers are shown (scale bar is 100 μm). (C) Perturbation effects of NAD+-producing enzymes expressed as CERES score across MM cell lines assessed via genomic CRISPR screening as part of the DepMap project. A CERES score of −1 identifies an essential gene. NAMPT and NAPRT have the highest dependency in MM cells. (D) Heat map of 797 patients with MM included in the CoMMpass study ordered in 3 groups by standardizing a NADome signature with a “min-max” method. Genes are categorized as either NAD+ consumers or producers, which are assigned to specific NAD+ biosynthetic pathways as in panel A. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of NADome signature, in terms of PFS and OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. Patients with high, intermediate (Int), and low MM expressing the signature are respectively reported in red, green, and blue. (F) Flux values of indicated NAD+ biosynthetic reactions obtained after integrating the MM-NADnet model with transcriptome data from patients with MM . The x-axis represents reactions, and the y-axis represents log2 flux values (μM/sec). Orange, green, light blue, and purple bars represent de novo– (R6a and R7), de novo–PH shared– (R8, R10 and R11), PH (R9), and salvage pathway–related (R19, R21, and R24) reactions, respectively. (G) Correlogram between gene log2 fold change (FC) values and metabolite log2 FC values. Rows represent metabolites and columns represent genes. The red color corresponds to positive correlation, the blue color corresponds to negative correlation, the area covered in the square corresponds to the absolute value of the correlation, and the black squares correspond to significant correlations (P < .05). (H) Analysis of NADome, NAMPT, and NAPRT expression in the CoMMpass database across patients with MM carrying indicated cytogenetic abnormalities. The expression of the NADome signature was standardized using the min-max method (gene based), and the mean gene set variation analysis (GSVA) score was subsequently calculated. The NAPRT and NAMPT expression data (expressed as log2 [TPM +1]) were obtained by selecting baseline expression data for each patient. Statistical significance between patient groups was calculated using the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P value is indicated in each insert.

NAD+ biosynthesis of MM cells predominantly relies on PH and salvage pathways, and its dysregulation predicts the clinical outcome. (A) Box plot of expression levels for indicated NAD+ biosynthetic genes in MM samples included in the CoMMpass study. Red, green, and purple bars represent de novo, PH-, and salvage pathway–related genes, respectively. Orange bars represent genes shared by all the NAD+-generating pathways. The abscissa represents the gene name, whereas the ordinate displays its expression as log10 transcripts per million (TPM). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of a representative BM biopsy collected from patients with NDMM. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), GIEMSA staining, along with CD138, NADSYN, NAPRT, and NAMPT markers are shown (scale bar is 100 μm). (C) Perturbation effects of NAD+-producing enzymes expressed as CERES score across MM cell lines assessed via genomic CRISPR screening as part of the DepMap project. A CERES score of −1 identifies an essential gene. NAMPT and NAPRT have the highest dependency in MM cells. (D) Heat map of 797 patients with MM included in the CoMMpass study ordered in 3 groups by standardizing a NADome signature with a “min-max” method. Genes are categorized as either NAD+ consumers or producers, which are assigned to specific NAD+ biosynthetic pathways as in panel A. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of NADome signature, in terms of PFS and OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. Patients with high, intermediate (Int), and low MM expressing the signature are respectively reported in red, green, and blue. (F) Flux values of indicated NAD+ biosynthetic reactions obtained after integrating the MM-NADnet model with transcriptome data from patients with MM . The x-axis represents reactions, and the y-axis represents log2 flux values (μM/sec). Orange, green, light blue, and purple bars represent de novo– (R6a and R7), de novo–PH shared– (R8, R10 and R11), PH (R9), and salvage pathway–related (R19, R21, and R24) reactions, respectively. (G) Correlogram between gene log2 fold change (FC) values and metabolite log2 FC values. Rows represent metabolites and columns represent genes. The red color corresponds to positive correlation, the blue color corresponds to negative correlation, the area covered in the square corresponds to the absolute value of the correlation, and the black squares correspond to significant correlations (P < .05). (H) Analysis of NADome, NAMPT, and NAPRT expression in the CoMMpass database across patients with MM carrying indicated cytogenetic abnormalities. The expression of the NADome signature was standardized using the min-max method (gene based), and the mean gene set variation analysis (GSVA) score was subsequently calculated. The NAPRT and NAMPT expression data (expressed as log2 [TPM +1]) were obtained by selecting baseline expression data for each patient. Statistical significance between patient groups was calculated using the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P value is indicated in each insert.

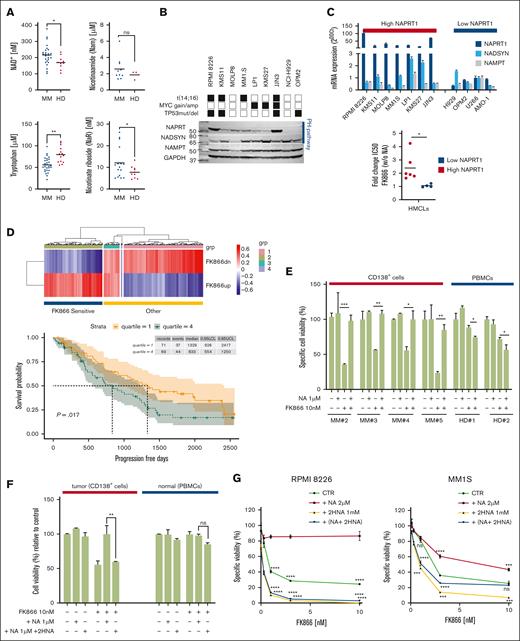

NAPRT targeting makes MM cells more sensitive to NAD+-lowering agents

Previous studies showed that targeting NAMPT with FK866 is effective against MM but spares noncancerous cells.16,17 However, its clinical success is hindered by variations in NAD+ precursor levels, influenced by diet, microbiota, and alternative NAD+ production pathways in tumors.15,25-27,35-41 We measured, by LC-MS/MS, NAD+ metabolites in BM samples from patients with MM and healthy donors and found higher NAD+ and NAM levels than control, with reversed amounts of tryptophan. Conversely, NA was undetectable in all tested samples, likely because of its rapid intracellular uptake, as well as NR, whereas nicotinic acid riboside (NAR) circulating levels were elevated in patient samples, suggesting a role for this NAD+ precursor in supporting energetic landscape of these tumor cells42 (Figure 2A). Considering the large number of enzymes and relative substrates acting in NAD+ biosynthesis, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the more branches are affected, the greater the injury results. We then tested a comprehensive NAD+ depletion strategy and confirmed that MM cells express enzymes from both the NAM salvage and PH pathways (Figure 2B). Although NAMPT and NAD synthetase 1 were uniformly expressed, a greater heterogeneity was observed regarding NAPRT levels, with the highest amounts found in those cell lines harboring t(14;16). A more focused messenger RNA (mRNA) analysis distinctly categorized a panel of human myeloma cell lines into low- and high-NAPRT–expressing groups, thus suggesting differences in their ability to use NAM or NA as NAD+ precursors. Indeed, the addition of NA made high-NAPRT–expressing cells more resistant to FK866; in contrast, no difference in terms of drug sensitivity was observed in cells carrying lower NAPRT levels at baseline (Figures 2C; supplemental Figure 5). To highlight the translational relevance of these data, FK866-induced transcriptome changes described in GSE9663643 were processed to infer patients with MM included in the CoMMpass data set. An enrichment analysis identified a group of patients with an FK866-specific signature (FK866up and FK866dn, respectively), resembling drug-treated cells (FK866 treated-like), reported as sensitive over those with different gene levels. Clinical analyses revealed that the FK866-sensitive signature resulted in better PFS and OS among patients with lower expression of NAPRT over those with higher levels (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 6; P = .017 and P = .032, respectively). Next, we tested the effects of FK866, in the presence or absence of NA, on primary plasma cells from patients with MM. As reported, NA supplementation reduced FK866’s effectiveness in MM samples. Furthermore, although FK866 was also found to be slightly active on peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors, the addition of NA did not save these cells (Figure 2E). Blood metabolites affect the tumor environment with interaction between NA and NAM that might affect the antitumor efficiency of NAMPT inhibitors (NAMPT-is).27 Thus, we tested the effect of NA supplementation on patient samples in combination with 2-hydroxynicotinic acid (2-HNA), a structural analog of NA previously reported to inhibit NAPRT enzymatic activity.19 As predicted, although NA addition fully rescued the anti-MM activity of FK866, its antitumor activity was retained in the presence of 2-HNA; a similar strategy did not have a significant effect on healthy peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Figure 2F). Finally, we confirmed these data on NAPRT-expressing cell lines as well and observed that the 2-HNA and FK866 combo were more effective than either agent alone in both cases (Figure 2G). These findings suggest that dual NAMPT/NAPRT inhibition is more effective than single-agent strategies in MM.

NAPRT targeting makes MM cells more sensitive to NAD+-lowering agents. (A) Quantification of indicated extracellular NAD+ metabolites in BM plasma derived from 15 patients with NDMM and 10 healthy donors, using LC-MS/MS. Data are mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .04 (Welch test), ∗∗P = .007 (t test). (B) Western blot (WB) showing indicated protein expression across a panel of MM cell lines with different genetic backgrounds (black and white squares refer to presence or absence of indicated abnormalities, respectively). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (bottom blot). One representative experiment is shown. (C) NAPRT, NADSYN, and NAMPT mRNA levels were evaluated in a panel of HMCLs by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using the 2-ΔΔCt method, with normalization to GAPDH. MM cells are divided into low- and high-NAPRT–expressing cells (top); the bottom panel shows the ratio (FC) of FK866 50% inhibitory concentration value for all the tested MM cell lines in the presence vs absence of NA (0.5 μM) supplementation. (D) Heat map showing FK866 activity signature expression in patients with MM derived from the CoMMpass data set grouped by GSVA method as FK866-sensitive patients (a group of patients with gene expression in accordance with FK866 treatment). “Other” includes patients with nonoverlapping profiles (top). Kaplan-Meyer curves of the PFS probability of FK866-sensitive patients, divided into quartiles for their expression of NAPRT. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value (log-rank test). First and fourth quartiles of NAPRT expression are represented in red and blue, respectively (bottom). (E) CD138+ primary cells from patients with MM (3 NDMM and 1 RRMM) and PBMCs from healthy donor (HD; n = 2), were treated with the indicated dose of FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (1 μM) for 96 hours and assessed for cell viability using CTG. (F) MM tumor (CD138+) and normal (PBMCs) cells were treated as in panel E, alone and in combination with the NAPRT inhibitor 2HNA (1 mM), and assessed for cell viability using CTG. (G) RPMI 8226 and MM1S NAPRT–expressing cells were treated with different concentrations of FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (2 μM), 2HNA (1 mM), and their combination for 72 hours. Cell viability was assessed using an MTS-based assay. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; unpaired t test. CTG, CellTiter-Glo; HMCLs, human myeloma cell lines; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium assay; ns, not significant; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; RRMM, relapsed refractory MM.

NAPRT targeting makes MM cells more sensitive to NAD+-lowering agents. (A) Quantification of indicated extracellular NAD+ metabolites in BM plasma derived from 15 patients with NDMM and 10 healthy donors, using LC-MS/MS. Data are mean ± standard deviation; ∗P < .04 (Welch test), ∗∗P = .007 (t test). (B) Western blot (WB) showing indicated protein expression across a panel of MM cell lines with different genetic backgrounds (black and white squares refer to presence or absence of indicated abnormalities, respectively). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control (bottom blot). One representative experiment is shown. (C) NAPRT, NADSYN, and NAMPT mRNA levels were evaluated in a panel of HMCLs by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using the 2-ΔΔCt method, with normalization to GAPDH. MM cells are divided into low- and high-NAPRT–expressing cells (top); the bottom panel shows the ratio (FC) of FK866 50% inhibitory concentration value for all the tested MM cell lines in the presence vs absence of NA (0.5 μM) supplementation. (D) Heat map showing FK866 activity signature expression in patients with MM derived from the CoMMpass data set grouped by GSVA method as FK866-sensitive patients (a group of patients with gene expression in accordance with FK866 treatment). “Other” includes patients with nonoverlapping profiles (top). Kaplan-Meyer curves of the PFS probability of FK866-sensitive patients, divided into quartiles for their expression of NAPRT. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value (log-rank test). First and fourth quartiles of NAPRT expression are represented in red and blue, respectively (bottom). (E) CD138+ primary cells from patients with MM (3 NDMM and 1 RRMM) and PBMCs from healthy donor (HD; n = 2), were treated with the indicated dose of FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (1 μM) for 96 hours and assessed for cell viability using CTG. (F) MM tumor (CD138+) and normal (PBMCs) cells were treated as in panel E, alone and in combination with the NAPRT inhibitor 2HNA (1 mM), and assessed for cell viability using CTG. (G) RPMI 8226 and MM1S NAPRT–expressing cells were treated with different concentrations of FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (2 μM), 2HNA (1 mM), and their combination for 72 hours. Cell viability was assessed using an MTS-based assay. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P ≤ .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; unpaired t test. CTG, CellTiter-Glo; HMCLs, human myeloma cell lines; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium assay; ns, not significant; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; RRMM, relapsed refractory MM.

NAPRT depletion reduces intracellular NAD+ content and sensitizes MM cells to NAMPT-is in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model

To investigate the role of NAPRT in MM cells, we established an in vitro system using RNA interference with 2 different NAPRT-targeting short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). As shown in Figure 3A, successful silencing with both shRNAs was confirmed at the mRNA and protein levels in RPMI8226 cells, although NAPRT-sh2 was generally more effective with no effects on NAMPT expression (data not shown). After NAPRT silencing, the intracellular NAD+ content and cell viability were measured at baseline and after FK866 exposure without NA addition. As shown in Figure 3B, NAPRT silencing resulted in a mild NAD+ shortage with NA failing to induce an intracellular NAD+ increase; instead, FK866 exposure led to significant NAD+ depletion that was more pronounced in NAPRT-depleted cells. Importantly, the rescue effect obtained with NA addition was conserved in scramble control cells but was lost in NAPRT-silenced cells thus suggesting the inability of the latter to fuel the PH pathway, despite the addition of its specific substrate. As with 2-HNA exposure, NAPRT silencing significantly sensitized MM cells to FK866 in terms of cell viability, recreating the same effect observed with the chemical approach (Figure 3C). Similar results were observed in an additional cellular model represented by MOLP8 (supplemental Figure 7A-C). We then aimed at confirming these findings in vivo by establishing a MM xenograft model. To this end, we subcutaneously injected MM1S cells transduced with scramble or NAPRT-sh2 into nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice. After tumor development, mice were randomized to be treated with the vehicle control (dimethyl sulfoxide) or FK866 (30 mg/kg; Figure 3D)17. As shown in Figure 3E, in mice that were xenografted with NAPRT-silenced cells, FK866 treatment significantly reduced tumor growth. Conversely, FK866 was less effective in those animals bearing tumor cells transduced with scramble control. Consistent with these results, benefits were observed in terms of mouse survival as well: mice carrying NAPRT-silenced tumors demonstrated an increased survival after FK866 treatment compared with mice bearing control tumors (65.5 and 59.5 days, respectively; P = .011, log-rank Mantel-Cox test; Figure 3F). Altogether, these data support NAPRT modulation as a promising strategy to improve the anti-MM activity of NAMPT-is.

NAPRT silencing reduces intracellular NAD+ content and sensitizes MM cells to NAMPT-i in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model. (A) In RPMI 8226 cells, NAPRT depletion was achieved using 2 different shRNA (sh2 and sh5) specific for NAPRT or scrambled control. NAPRT silencing was validated using qPCR (left panel) and WB (right panel) analyses. (B) Isogenic RPMI 8226 cells as in panel A were treated for 48 hours with FK866 in the presence or absence of NA and their combinations. Then, intracellular NAD+ level was determined by cyclic enzymatic assay, expressed in nmol and normalized for cell mass (mg of total proteins). (C) Cell viability of scramble, shNAPRT 2, and shNAPRT 5 RPMI 8226 cells treated with FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (2 μM), 2-HNA (1 mM), or their combos for 72 hours was measured with MTS assay and presented as a percentage of control (specific control). (D) Schematic representation of the in vivo experiment. (E) Female NOD/SCID J mice (8 weeks of age) were injected subcutaneously in both flanks with MM1S cells transduced with shNAPRT2 or scramble (4.5 × 106 viable cells). After the detection of tumors, mice from both groups were randomized and treated with either vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; scramble, n = 5; shNAPRT 2, n = 6) or FK866 (30 mg/kg; scramble and shNAPRT 2, n = 6) administered intraperitoneally twice a day for 18 days. Tumor volume was evaluated by caliper measurement. A significant delay in tumor growth was observed after treatment in shNAPRT2 cell–xenografted mice compared with scramble (∗∗∗P = .0008). Data represent the mean tumor volume ± standard deviation. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of xenograft mice bearing MM1S scramble and shNAPRT 2 tumors. Mice carrying NAPRT-silenced tumors showed increased survival after FK866 treatment compared with mice bearing control tumors (∗P = .011). n indicates the number of tumors per treatment group. Data were analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test for panels A-B,E or by log-rank Mantel-Cox test for panel F. For panels A-C, data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001; unpaired t test. CTR, control; NOD/SCID, nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency; ns, not significant; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

NAPRT silencing reduces intracellular NAD+ content and sensitizes MM cells to NAMPT-i in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model. (A) In RPMI 8226 cells, NAPRT depletion was achieved using 2 different shRNA (sh2 and sh5) specific for NAPRT or scrambled control. NAPRT silencing was validated using qPCR (left panel) and WB (right panel) analyses. (B) Isogenic RPMI 8226 cells as in panel A were treated for 48 hours with FK866 in the presence or absence of NA and their combinations. Then, intracellular NAD+ level was determined by cyclic enzymatic assay, expressed in nmol and normalized for cell mass (mg of total proteins). (C) Cell viability of scramble, shNAPRT 2, and shNAPRT 5 RPMI 8226 cells treated with FK866 in the presence or absence of NA (2 μM), 2-HNA (1 mM), or their combos for 72 hours was measured with MTS assay and presented as a percentage of control (specific control). (D) Schematic representation of the in vivo experiment. (E) Female NOD/SCID J mice (8 weeks of age) were injected subcutaneously in both flanks with MM1S cells transduced with shNAPRT2 or scramble (4.5 × 106 viable cells). After the detection of tumors, mice from both groups were randomized and treated with either vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; scramble, n = 5; shNAPRT 2, n = 6) or FK866 (30 mg/kg; scramble and shNAPRT 2, n = 6) administered intraperitoneally twice a day for 18 days. Tumor volume was evaluated by caliper measurement. A significant delay in tumor growth was observed after treatment in shNAPRT2 cell–xenografted mice compared with scramble (∗∗∗P = .0008). Data represent the mean tumor volume ± standard deviation. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of xenograft mice bearing MM1S scramble and shNAPRT 2 tumors. Mice carrying NAPRT-silenced tumors showed increased survival after FK866 treatment compared with mice bearing control tumors (∗P = .011). n indicates the number of tumors per treatment group. Data were analyzed by 2-tailed Student t test for panels A-B,E or by log-rank Mantel-Cox test for panel F. For panels A-C, data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. ∗P ≤ .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001; unpaired t test. CTR, control; NOD/SCID, nonobese diabetic severe combined immunodeficiency; ns, not significant; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

NAPRT deficiency is associated with increased oxidative stress in MM cells

The aforementioned results indicate a key role for the PH pathway rate-limiting enzyme, NAPRT, in the NAD+ output of MM cells. Consistent with this notion, NAPRT expression levels showed an adverse impact on the clinical outcome of the patients with MM included in the CoMMpass data set: specifically, patients with NAPRT expression levels in the highest quartile showed a significantly poorer OS and PFS than the others (Figures 4A; supplemental Figure 8; P = .014 and P = .058, respectively; log-rank test). PROGENy analysis of the differentially expressed transcripts between the lowest and the highest expression quartiles,44 showed significant enrichment for genes related to nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and tumor necrosis factor α signaling in the former, thus providing evidence for the occurrence of a distinctive signature in these patients (Figure 4B). Indeed, studies of nuclear extracts from MM cell lines confirmed higher nuclear levels of NF-κB in NAPRT-silenced cells than in control cells (supplemental Figure 9). Accumulating evidence shows that NF-κB, which has a key role in regulating different cellular processes, is frequently dysregulated in MM cells, supporting its targeting as a well-established anti-MM strategy.45 Among other mechanisms, NF-κB can be activated by high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and in turn, NF-κB promotes an antioxidant transcription program.46 A targeted-transcriptomic analysis of NAPRT-silenced cells revealed increased expression of genes encoding for factors that are involved in the response to ROS such as c-Jun, SOD1-2, HSPA6, Nrf2, and PGC1-α as compared with control cells (Figure 4C). Furthermore, we screened the overall oxidative stress by using dichlorofluorescein and CellROX dyes and found that NAPRT silencing globally increased cellular ROS levels over control values (Figure 4D). Similar results were observed in another cell model (supplemental Figure 10). Previous studies show that NAMPT-is induce antitumor activity via ROS increase: NAD+ depletion raises ROS levels, causing mitochondrial membrane depolarization and adenosine triphosphate depletion.47 We hypothesized that elevated ROS in NAPRT-depleted tumors may increase FK866 sensitivity. Measurements confirmed higher ROS levels, especially H2O2, in FK866-treated, NAPRT-depleted cells (Figure 4E). Using antioxidants, we found that catalase reversed FK866’s cytotoxic effect only in control cells, indicating that ROS are key in FK866 sensitivity of NAPRT-depleted MM cells (Figure 4F). Consistent with the hypothesis that NAPRT silencing would cause reduced ability to scavenge ROS and increase their levels, NAPRT-silenced cells were found to have higher levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), and reduced activity of enzymes involved in the endogenous antioxidant defenses (glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase) were detected, especially with FK866 treatment (Figure 4G-I). Importantly, all these results were confirmed in an additional silenced cell line model (supplemental Figure 11). To monitor the oxidative stress induced by these stimuli, we quantified the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH and GSSG, respectively): remarkably, NAPRT depletion caused a decrease in the GSH:GSSG ratio, which became more pronounced in FK866-treated cells (Figure 4J; supplemental Figure 12A). Alongside these changes, a drop in the NADPH/NADP+ ratio was observed, indicating that NAPRT silencing impairs redox homeostasis in MM cells, a disruption that was further intensified by FK866 treatment (Figure 4K).

NAPRT deficiency is associated with increased oxidative stress in MM cells. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of low NAPRT levels in terms of OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value (log-rank test). First and fourth quartiles of NAPRT expression are represented in red and blue, respectively. (B) PROGENy (pathway responsive genes for activity inference) was used to infer pathway activities from CoMMpass RNA-sequencing data, comparing patients with MM with low NAPRT expression (first quartile, red) with those with high expression (fourth quartile, blue). Normalized enrichment scores (NES) for each pathway were displayed. High NES indicate high enrichment. (C) Oxidative stress-related genes mRNA levels were evaluated by qRT-PCR using the 2-ΔΔCt method, with normalization to GAPDH as a housekeeping gene, in scramble and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells. (D) Detection of human reactive oxygen species (hROS) in scramble and NAPRT-silenced RPMI 8226 cells using CellROX Deep Red and 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA; for H2O2 detection) fluorescent probes. (E) Time-dependent detection of indicated hROS productions after FK866 treatment (10 nM) in control and NAPRT-silenced MM cells. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and cytosolic (cO2−) were detected by flow cytometry using DCFDA and dihydroethidium fluorescent probes, respectively. (F) Scramble and shNAPRT #2 RPMI 8226 cells were incubated with or without exogenous catalase (CAT; H2O2 scavenger, 1000 U/mL) with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (3-10 nM). Cell viability was measured after 96 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using annexin V (AV)/propidium iodide (PI) staining. (G-K) Oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde (MDA) (G), activities of antioxidant enzymes (glutathione peroxidase [GPX], glutathione reductase [GR]) (H-I), and GSH:GSSG and NADPH:NADP+ ratios (J-K) were assessed in control and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increased concentrations of FK866 (2-3 nM) for 24 hours. Panels C-G represent means (±SD) of duplicate experiments; panels H-L show representative experiments as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; unpaired t test. ns, not significant.

NAPRT deficiency is associated with increased oxidative stress in MM cells. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of low NAPRT levels in terms of OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value (log-rank test). First and fourth quartiles of NAPRT expression are represented in red and blue, respectively. (B) PROGENy (pathway responsive genes for activity inference) was used to infer pathway activities from CoMMpass RNA-sequencing data, comparing patients with MM with low NAPRT expression (first quartile, red) with those with high expression (fourth quartile, blue). Normalized enrichment scores (NES) for each pathway were displayed. High NES indicate high enrichment. (C) Oxidative stress-related genes mRNA levels were evaluated by qRT-PCR using the 2-ΔΔCt method, with normalization to GAPDH as a housekeeping gene, in scramble and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells. (D) Detection of human reactive oxygen species (hROS) in scramble and NAPRT-silenced RPMI 8226 cells using CellROX Deep Red and 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA; for H2O2 detection) fluorescent probes. (E) Time-dependent detection of indicated hROS productions after FK866 treatment (10 nM) in control and NAPRT-silenced MM cells. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and cytosolic (cO2−) were detected by flow cytometry using DCFDA and dihydroethidium fluorescent probes, respectively. (F) Scramble and shNAPRT #2 RPMI 8226 cells were incubated with or without exogenous catalase (CAT; H2O2 scavenger, 1000 U/mL) with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (3-10 nM). Cell viability was measured after 96 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using annexin V (AV)/propidium iodide (PI) staining. (G-K) Oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde (MDA) (G), activities of antioxidant enzymes (glutathione peroxidase [GPX], glutathione reductase [GR]) (H-I), and GSH:GSSG and NADPH:NADP+ ratios (J-K) were assessed in control and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increased concentrations of FK866 (2-3 nM) for 24 hours. Panels C-G represent means (±SD) of duplicate experiments; panels H-L show representative experiments as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; unpaired t test. ns, not significant.

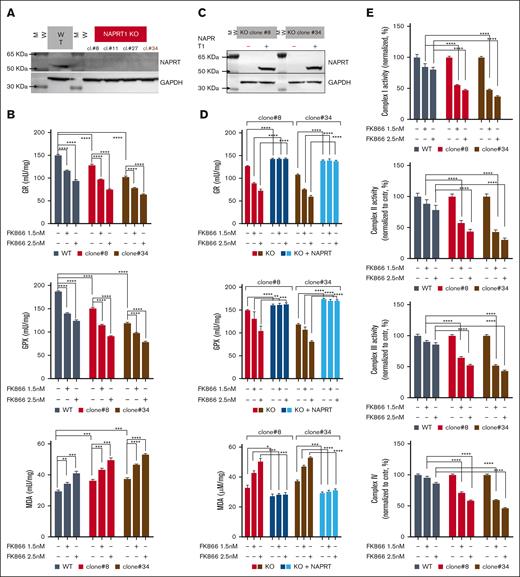

NAPRT activity is crucial for redox homeostasis and oxidative metabolism of MM cells, thus influencing the anti-MM activity of NAD+-lowering agents

Because NAPRT is highly effective in sustaining NAD+ levels, its complete knockdown is essential to achieve sensitization to NAMPT-is.48 Accordingly, we performed CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to generate NAPRT-KO cell lines that were then tested with FK866 treatment: the extensive NAD+ depletion increased MDA levels, further weakened endogenous antioxidant defenses, and lowered GSH:GSSG levels (Figure 5A-B and supplemental Figure 12B-C). To support these findings, we added-back NAPRT in both KO clones by transducing them with a lentiviral NAPRT-overexpressing vector. The reconstituted cells restored NAPRT protein levels along with their antioxidant defenses capabilities and GSH:GSSG ratio, whereas reduced MDA levels at baseline and after FK866 exposure as well (Figure 5C-D; supplemental Figure 12D). These results indicate that the loss and gain of NAPRT strongly regulate redox homeostasis in MM cells. The TCA cycle generates various metabolites using major carbohydrate sources. It occurs in mitochondria and provides large amounts of energy by producing reduced coenzymes to allow proton motive force transfer and the generation of a gradient dissipated for the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate. By transitioning between its oxidized (NAD+) and reduced (NADH) forms, NAD+ acts as a key electron transporter in cellular energy pathways.49-50 Thus, we investigated the respiratory capacity of NAPRT-KO cells after NAMPT inhibition. As shown in Figure 5E, the activities of complex 1, 2, 3, and 4 in CRISPR-Cas9 NAPRT-KO were significantly impaired during FK866 treatment, which, in turn, made these cells more sensitive to the oxidative phosphorylation inhibitor IACS-01075912 than control cells (Figure 5F).

NAPRT activity is crucial for redox homeostasis and oxidative metabolism of MM cells thus influencing the anti-MM activity of NAD+-lowering agents. (A) KMS11 cells expressing inducible Cas9 were used to generate different clones of NAPRT-KO cells. WB analysis of wild type (WT) and indicated 4 different NAPRT-KO clones of KMS11 cells confirmed specific KO. Whole-cell lysates were collected and probed with NAPRT antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Antioxidant enzymes (GR and GPX) activities and MDA levels were assessed in WT and in 2 different KMS11 NAPRT-KO clones in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 24 hours. (C) Representative WB images of KO cells (clone#8 and #34) expressing NAPRT addbacks or KO cells. (D) indicated antioxidant enzymes activities and MDA levels were assessed in NAPRT added-back and in KO cells, in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 24 hours. (E) Mitochondrial complexes (I, II, III, and IV) activities normalized to specific control (expressed as percentage, %) measured in KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO cells (clone#8 and clone#34), in the presence of 1 μM NA with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 48 hours. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). (F) Specific viability of KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO cells (clone#8 and clone#34) in the presence of 1 μM NA, was assessed. Increasing doses of FK866 (0.8-1-1.4 nM) were administered, and after 24 hours, the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) inhibitor IACS010759 (0.6 μM) was either added for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was finally measured using an MTS-based assay. In the right panel, synergism of the same experiment was analyzed by Combenefit software, using the Lowe method. A representative experiment of 2 was shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001; unpaired t test. cl., clone.

NAPRT activity is crucial for redox homeostasis and oxidative metabolism of MM cells thus influencing the anti-MM activity of NAD+-lowering agents. (A) KMS11 cells expressing inducible Cas9 were used to generate different clones of NAPRT-KO cells. WB analysis of wild type (WT) and indicated 4 different NAPRT-KO clones of KMS11 cells confirmed specific KO. Whole-cell lysates were collected and probed with NAPRT antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Antioxidant enzymes (GR and GPX) activities and MDA levels were assessed in WT and in 2 different KMS11 NAPRT-KO clones in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 24 hours. (C) Representative WB images of KO cells (clone#8 and #34) expressing NAPRT addbacks or KO cells. (D) indicated antioxidant enzymes activities and MDA levels were assessed in NAPRT added-back and in KO cells, in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 24 hours. (E) Mitochondrial complexes (I, II, III, and IV) activities normalized to specific control (expressed as percentage, %) measured in KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO cells (clone#8 and clone#34), in the presence of 1 μM NA with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (1.5-2.5 nM) for 48 hours. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6). (F) Specific viability of KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO cells (clone#8 and clone#34) in the presence of 1 μM NA, was assessed. Increasing doses of FK866 (0.8-1-1.4 nM) were administered, and after 24 hours, the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) inhibitor IACS010759 (0.6 μM) was either added for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was finally measured using an MTS-based assay. In the right panel, synergism of the same experiment was analyzed by Combenefit software, using the Lowe method. A representative experiment of 2 was shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001; unpaired t test. cl., clone.

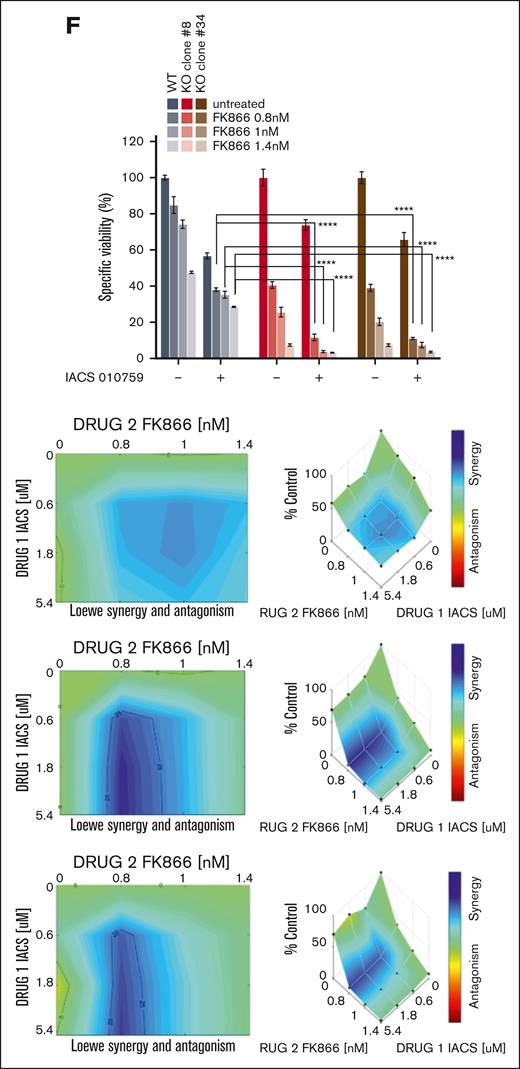

NAD+ starvation enhances melphalan’s anti-MM activity, thus improving high-dose melphalan-based programs’ efficacy

Oxidative stress destabilizes MM cell DNA, making them highly reliant on NAD+-dependent enzymes such as PARP1/2 and SIRTuins for genomic integrity.51-53 We used γ-H2A.X staining in CRISPR-Cas9 NAPRT-KO cells to assess DNA damage at baseline and after FK866 treatment, showing increased DNA damage in NAPRT-KO cells, further intensified by FK866, indicating pervasive DNA damage from NAD+ depletion (Figure 6A). We then tested the impact of NAPRT depletion on MM cell sensitivity to melphalan, a genotoxic agent used in autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) conditioning, finding that KO cells were more vulnerable, suggesting that targeting NAD+ biosynthesis exacerbates DNA damage (Figure 6B). Consistent with these data, we tested the effect of a comprehensive NAD+ restriction on the anti-MM activity of melphalan: simultaneous inhibition of PH and salvage pathways synergistically increased the antitumor activity of chemotherapy. Interestingly, NAPRT addback rescued KO phenotypes, particularly after NAMPT inhibitor addition, thus supporting the relevance of NAD+ metabolic restriction in MM cells chemotherapy sensitivity (Figure 6C). As result, the combination of 2-HNA and FK866 partially rescued melphalan sensitivity in another cell line model and in resistant MM cells (LR5; supplemental Figure 13A-C). To support translational relevance of these findings, we reanalyzed the CoMMpass data set by focusing on transplant-eligible patients receiving high-dose melphalan (HDM). As shown in Figure 6D, better outcomes were found in patients exhibiting FK866-sensitive signature and lower NAPRT expression; in contrast, no benefit was observed in non-FK866-sensitive patients receiving the same treatment (P = .003 and P = .57, respectively). In line with these data, RNA-sequencing analysis on our independent cohort of 20 patients with NDMM exposed to melphalan confirmed higher overall response rates among patients resembling FK866-sensitive cells signature, which was further improved (partial response or better) in the presence of lower NAPRT mRNA levels (Figure 6E-F; P <.023). Overall, these data suggest that complete NAD+ starvation via combined NAPRT and NAMPT inhibition could improve the efficacy of HDM-based regimens and serve as a predictive biomarker for outcomes of patients with NDMM who are transplant eligible.

NAD+ starvation enhances the anti-MM activity of genotoxic stress and results in improved HDM-based programs’ efficacy. (A) Foci of DNA damage in KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO (clone#8) cells were stained by immunofluorescence by γ-H2A.X marker (green) staining, in the presence of NA (1 μM), with or without FK866 (10 nM, 48 hours). Q-nuclear (red) was used as a nuclear reference. On the right of the panel, a graph of the quantification of foci is included. Original magnification 60× is shown and the scale bar is 20 μm. (B) WT and NAPRT-KO clone#8 cells were incubated with melphalan (20 μM). Cell death was measured after 48 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using AV/PI staining. (C) Specific viability of WT, NAPRT-KO, and NAPRT–added-back KO KMS11 cells (clone#8), in the presence of NA (1 μM), was assessed: increasing doses of FK866 (0.8-1-1.4 nM) were administered, and after 24 hours, the alkylating drug melphalan (20 μM) was either added or not for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was ultimately assessed using the annexin V/PI method. Analysis of drug synergism performed with Combenefit (HSA model) is reported in the panel on the right. (D) Kaplan-Meyer curves of the PFS probability of transplant-eligible patients receiving HDM divided as FK866 sensitive (on the left, n = 126) or not sensitive (on the right, n = 216) in the CoMMpass data set, according to their NAPRT mRNA levels (first and fourth quartiles are represented in red and blue, respectively). Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. (E-F) Heat map showing FK866 activity signature expression in 20 patients with melphalan-exposed NDMM grouped using GSVA method: patients with gene expression in accordance with FK866 treatment are highlighted in red as “FK866 sensitive.” Overall response rate (ORR; includes complete response [CR]; very good partial response [VGPR]; stable disease [SD]; partial response [PR]; and progressive disease [PD]) was measured in profiled patients with MM with a focus on NAPRT expression: patients achieving at least PR after HDM carried overlapping profiling with FK866-sensitive cells with lower NAPRT mRNA levels than others. In panels A-B,D a representative experiment of 2 was shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Unpaired t test was used for panels A,F (∗P ≤ .05).

NAD+ starvation enhances the anti-MM activity of genotoxic stress and results in improved HDM-based programs’ efficacy. (A) Foci of DNA damage in KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO (clone#8) cells were stained by immunofluorescence by γ-H2A.X marker (green) staining, in the presence of NA (1 μM), with or without FK866 (10 nM, 48 hours). Q-nuclear (red) was used as a nuclear reference. On the right of the panel, a graph of the quantification of foci is included. Original magnification 60× is shown and the scale bar is 20 μm. (B) WT and NAPRT-KO clone#8 cells were incubated with melphalan (20 μM). Cell death was measured after 48 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using AV/PI staining. (C) Specific viability of WT, NAPRT-KO, and NAPRT–added-back KO KMS11 cells (clone#8), in the presence of NA (1 μM), was assessed: increasing doses of FK866 (0.8-1-1.4 nM) were administered, and after 24 hours, the alkylating drug melphalan (20 μM) was either added or not for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was ultimately assessed using the annexin V/PI method. Analysis of drug synergism performed with Combenefit (HSA model) is reported in the panel on the right. (D) Kaplan-Meyer curves of the PFS probability of transplant-eligible patients receiving HDM divided as FK866 sensitive (on the left, n = 126) or not sensitive (on the right, n = 216) in the CoMMpass data set, according to their NAPRT mRNA levels (first and fourth quartiles are represented in red and blue, respectively). Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. (E-F) Heat map showing FK866 activity signature expression in 20 patients with melphalan-exposed NDMM grouped using GSVA method: patients with gene expression in accordance with FK866 treatment are highlighted in red as “FK866 sensitive.” Overall response rate (ORR; includes complete response [CR]; very good partial response [VGPR]; stable disease [SD]; partial response [PR]; and progressive disease [PD]) was measured in profiled patients with MM with a focus on NAPRT expression: patients achieving at least PR after HDM carried overlapping profiling with FK866-sensitive cells with lower NAPRT mRNA levels than others. In panels A-B,D a representative experiment of 2 was shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Unpaired t test was used for panels A,F (∗P ≤ .05).

Discussion

NAD+ regulates key cellular processes such as growth and metabolism, with its levels tightly balanced through consumption and biosynthesis. Disrupting NAD+ homeostasis is a druggable vulnerability, offering an innovative intervention strategy. Cancer cells manage this dependency through interconnected biochemical networks, making single-target approaches ineffective. Consistent with this, current NAD+-lowering agents targeting NAMPT have shown limited success in patients.54,55 Our study, combining mathematical modeling with in vitro and in vivo analysis, demonstrates that simultaneous targeting of multiple NAD+ biosynthetic pathways enhance anti-MM effects and boosts genotoxic agent efficacy. Our findings also identify MM-specific dependencies on both the PH and salvage pathways, whose dysregulation affects clinical outcomes. Additionally, NAPRT expression was strongly correlated with NAD+ metabolite levels in the NADnet model. Recent studies have shown that more aggressive disease exhibit increased metabolic dependencies.56-57 Indeed, a chromosomal abnormalities screen of patients with MM included in the CoMMpass data set revealed t(14;16) significantly enriched among patients with higher NADome score and NAMPT and NAPRT expression, whereas other categories were almost unaffected. Overall, these data made us speculate that interfering with the activity of both PH and salvage pathways, rate-limiting enzymes could represent an effective strategy to treat patients with MM, especially those with t(14;16). Although the molecular link between t(14;16) translocation and NAD+ biosynthesis is unclear, it may involve transcription factors regulating NAD+ producers NAPRT and NAMPT, which are upregulated in these patients.58 In vitro and in vivo, targeting NAPRT sensitizes MM cells to NAMPT inhibitors, suggesting a cooperative strategy between these pathways. These findings support blocking the PH route to enhance NAMPT inhibitor efficacy. Because NA is primarily supplied through dietary intake, we propose testing dietary NA restriction in clinical trials to boost NAMPT inhibitor activity in MM, after safety evaluation. We then functionally investigated NAPRT-depleted cells and observed that NAPRT depletion was associated with impaired effectiveness of endogenous antioxidant defenses, as evidenced by reduced activities of glutathione reductase and glutathione peroxidase, as well as a decrease in the ratio between GSH and GSSG. Additionally, we noted a consistent increase in oxidative stress and DNA damage markers, which resulted further increased after FK866 treatment. Due to the tight link between metabolism and DNA repair mechanisms,59 NAD+ restriction achieved by NAMPT/NAPRT dual inhibition boosted the genotoxic stress activity of melphalan treatment, likely due to reduced efficiency of DNA repair mechanisms that require high NAD+ levels to function properly.60 Accordingly, transcriptomic analyses revealed deeper responses with HDM-based therapies in those patients carrying a FK866-sensitive signature and lower NAPRT mRNA levels, thus supporting the clinical relevance of the identified strategy. Human blood concentrations of vitamin B3 (NA, NAM, NR, and NAR), influenced by diet and microbiota, affect the efficacy of NAD+-lowering agents.12,61 In BM samples from patients with MM and healthy donors, significant variability was found, with higher NAM and NAR levels in patients. Surprisingly, NA and NR were undetectable, likely because of their high cellular uptake. These results suggest that elevated BST1 activity in BM stromal cells may support NAD+ synthesis via the PH pathway.42,62 Recent evidence shows NAD+ metabolism also influences bacterial infections, with gut microbiota generating NA to enhance NAD+ production.27,40,41,63 This could affect the efficacy of HDM-based regimens in patients with MM. Antibiotics, by inhibiting NAPRT-mediated rescue effects, may improve the effectiveness of HDM strategies for ASCT-eligible patients. These findings align with previous research on the role of microbiota in modulating anti-MM therapies.64-67 Furthermore, a recent clinical trial showed that prophylactic levofloxacin improved therapy response and survival in patients with NDMM.68 Our data support the potential for microbiota-targeted strategies to enhance HDM effectiveness in ASCT-eligible patients. In conclusion, we demonstrate that metabolic NAD+ restriction resulting from dual NAMPT/NAPRT inhibition offers a promising approach to enhance the effectiveness of HDM-based regimens. Our study also opens the path for future clinical trials testing NA-free diets combined with metabolic drugs for patients with MM who are challenging to treat.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation for sharing the CoMMpass study data set.

This work was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG number 23438 [M.C.]), International Myeloma Society and Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation translational research award 2023, Italian Ministry of Health (GR-2016-02361523 [A.C.]), Associazione Italiana Leucemie Linfomi e Mieloma (AIL sezione di Genova) and University of Genoa, Italy.

Authorship

Contribution: D.S. and M.C. designed the research and wrote the manuscript; F.L. and E.G. performed the statistical and bioinformatic analyses; P.B. performed in vivo experiments; D.S., F.L., C.M., and G.G performed in vitro experiments; F.P, S.R., A.B., A. Nahimana, and S.B. performed metabolomics analyses; C.A. and C.N. performed mathematical modeling; L.M. performed immunohistochemistry analysis; C.V. and G.S. performed RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis; A.C., S.A., F.G., M.F., and M.G. provided patient samples; M.P. performed immunofluorescence analysis; and A. Nencioni, M.G., M.A.D., E.A., and R.M.L. revised the final version of manuscript. C.N. is a co-founder of qBiome Research Pvt Ltd, IITM campus and HealthSeq Precision Medicine Pvt Ltd, IISc campus, which have no role in this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michele Cea, Clinic of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine and Specialties, University of Genoa, Viale Benedetto XV, 6, N/A 16132 Genoa, Italy; email: michele.cea@unige.it.

References

Author notes

The NADnet biomodel has been submitted to BioModels (ID MODEL2311140001). Proprietary RNA-sequencing data are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE248379).

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Michele Cea (michele.cea@unige.it).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![NAD+ biosynthesis of MM cells predominantly relies on PH and salvage pathways, and its dysregulation predicts the clinical outcome. (A) Box plot of expression levels for indicated NAD+ biosynthetic genes in MM samples included in the CoMMpass study. Red, green, and purple bars represent de novo, PH-, and salvage pathway–related genes, respectively. Orange bars represent genes shared by all the NAD+-generating pathways. The abscissa represents the gene name, whereas the ordinate displays its expression as log10 transcripts per million (TPM). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of a representative BM biopsy collected from patients with NDMM. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), GIEMSA staining, along with CD138, NADSYN, NAPRT, and NAMPT markers are shown (scale bar is 100 μm). (C) Perturbation effects of NAD+-producing enzymes expressed as CERES score across MM cell lines assessed via genomic CRISPR screening as part of the DepMap project. A CERES score of −1 identifies an essential gene. NAMPT and NAPRT have the highest dependency in MM cells. (D) Heat map of 797 patients with MM included in the CoMMpass study ordered in 3 groups by standardizing a NADome signature with a “min-max” method. Genes are categorized as either NAD+ consumers or producers, which are assigned to specific NAD+ biosynthetic pathways as in panel A. (E) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of NADome signature, in terms of PFS and OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. Patients with high, intermediate (Int), and low MM expressing the signature are respectively reported in red, green, and blue. (F) Flux values of indicated NAD+ biosynthetic reactions obtained after integrating the MM-NADnet model with transcriptome data from patients with MM . The x-axis represents reactions, and the y-axis represents log2 flux values (μM/sec). Orange, green, light blue, and purple bars represent de novo– (R6a and R7), de novo–PH shared– (R8, R10 and R11), PH (R9), and salvage pathway–related (R19, R21, and R24) reactions, respectively. (G) Correlogram between gene log2 fold change (FC) values and metabolite log2 FC values. Rows represent metabolites and columns represent genes. The red color corresponds to positive correlation, the blue color corresponds to negative correlation, the area covered in the square corresponds to the absolute value of the correlation, and the black squares correspond to significant correlations (P < .05). (H) Analysis of NADome, NAMPT, and NAPRT expression in the CoMMpass database across patients with MM carrying indicated cytogenetic abnormalities. The expression of the NADome signature was standardized using the min-max method (gene based), and the mean gene set variation analysis (GSVA) score was subsequently calculated. The NAPRT and NAMPT expression data (expressed as log2 [TPM +1]) were obtained by selecting baseline expression data for each patient. Statistical significance between patient groups was calculated using the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; P value is indicated in each insert.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/5/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024013425/5/m_blooda_adv-2024-013425-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1765897357&Signature=PpqJFXautSUJCV8gmoZxmCQjcmsowe5XW7R9AGHMA-W4c3WMkGsyfygxr2tQpVK1Q858uUNq2VEBCNnzJ23vV9N1qwJc4h7e-5GE98NbmvS6dAPVLMvIlR1rEANhFH0CTYzXMzKI7LBt7hChHm1t4XZSFJDextCAmbo~EQo3skZT1ARt93I38wa7vKGVrW6jaTJPeZ2fhl4r49vTZ6KlXkpCGm9EmSq6R572bzCreXkMZYFLEa2cBXJhFvwncitk61nJM-jzbo-azVvva0GD7bK60tzNKTjt3upviVqkexqvSpYYUdrtA-b80RyJSIBCq8ALA1D8MF~E3IIVRQ2-TQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![NAPRT deficiency is associated with increased oxidative stress in MM cells. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the prognostic impact of low NAPRT levels in terms of OS, using the CoMMpass data set. Log-rank test is used to compute the P value (log-rank test). First and fourth quartiles of NAPRT expression are represented in red and blue, respectively. (B) PROGENy (pathway responsive genes for activity inference) was used to infer pathway activities from CoMMpass RNA-sequencing data, comparing patients with MM with low NAPRT expression (first quartile, red) with those with high expression (fourth quartile, blue). Normalized enrichment scores (NES) for each pathway were displayed. High NES indicate high enrichment. (C) Oxidative stress-related genes mRNA levels were evaluated by qRT-PCR using the 2-ΔΔCt method, with normalization to GAPDH as a housekeeping gene, in scramble and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells. (D) Detection of human reactive oxygen species (hROS) in scramble and NAPRT-silenced RPMI 8226 cells using CellROX Deep Red and 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA; for H2O2 detection) fluorescent probes. (E) Time-dependent detection of indicated hROS productions after FK866 treatment (10 nM) in control and NAPRT-silenced MM cells. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and cytosolic (cO2−) were detected by flow cytometry using DCFDA and dihydroethidium fluorescent probes, respectively. (F) Scramble and shNAPRT #2 RPMI 8226 cells were incubated with or without exogenous catalase (CAT; H2O2 scavenger, 1000 U/mL) with or without increasing concentrations of FK866 (3-10 nM). Cell viability was measured after 96 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using annexin V (AV)/propidium iodide (PI) staining. (G-K) Oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde (MDA) (G), activities of antioxidant enzymes (glutathione peroxidase [GPX], glutathione reductase [GR]) (H-I), and GSH:GSSG and NADPH:NADP+ ratios (J-K) were assessed in control and NAPRT-silenced (sh2) RPMI 8226 cells in presence of 1 μM NA, with or without increased concentrations of FK866 (2-3 nM) for 24 hours. Panels C-G represent means (±SD) of duplicate experiments; panels H-L show representative experiments as mean ± SD (n = 6). ∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P ≤ .001; unpaired t test. ns, not significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/5/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024013425/5/m_blooda_adv-2024-013425-gr4.jpeg?Expires=1765897357&Signature=C-MwvDrN3gA1xymMS~nj8VrhIkJi6n-MXAk9~BwG6Byra52J828vgpmdprlcNbk-ypNHhi9hGjO4RklXGQPNJvkkRKVrvvfCQZzvYkcPXygaxZwMUkZacJcSsLjzOfCOhGMHBfWVRWB-Jv-ZxmnvWZWtQzU-rPeIIJCupBXu1bL4u6YYKcsQsKp-rDglGpwlTwkBtLlqAlOJdtYA19FEVvwTAesC521BC3szYE5YKdpOk1-GRAti6mPBhJoEKHQfIGL~nJKrFUFWUm~khblQmAtlQdc7BvdKT27C~Zt8f-HxYNJrza2QdAHkeamOFWqXxOmrVucNRk4GEaCK5z-~Wg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![NAD+ starvation enhances the anti-MM activity of genotoxic stress and results in improved HDM-based programs’ efficacy. (A) Foci of DNA damage in KMS11 WT and NAPRT-KO (clone#8) cells were stained by immunofluorescence by γ-H2A.X marker (green) staining, in the presence of NA (1 μM), with or without FK866 (10 nM, 48 hours). Q-nuclear (red) was used as a nuclear reference. On the right of the panel, a graph of the quantification of foci is included. Original magnification 60× is shown and the scale bar is 20 μm. (B) WT and NAPRT-KO clone#8 cells were incubated with melphalan (20 μM). Cell death was measured after 48 hours of drug exposure and assessed by flow cytometry using AV/PI staining. (C) Specific viability of WT, NAPRT-KO, and NAPRT–added-back KO KMS11 cells (clone#8), in the presence of NA (1 μM), was assessed: increasing doses of FK866 (0.8-1-1.4 nM) were administered, and after 24 hours, the alkylating drug melphalan (20 μM) was either added or not for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was ultimately assessed using the annexin V/PI method. Analysis of drug synergism performed with Combenefit (HSA model) is reported in the panel on the right. (D) Kaplan-Meyer curves of the PFS probability of transplant-eligible patients receiving HDM divided as FK866 sensitive (on the left, n = 126) or not sensitive (on the right, n = 216) in the CoMMpass data set, according to their NAPRT mRNA levels (first and fourth quartiles are represented in red and blue, respectively). Log-rank test is used to compute the P value. (E-F) Heat map showing FK866 activity signature expression in 20 patients with melphalan-exposed NDMM grouped using GSVA method: patients with gene expression in accordance with FK866 treatment are highlighted in red as “FK866 sensitive.” Overall response rate (ORR; includes complete response [CR]; very good partial response [VGPR]; stable disease [SD]; partial response [PR]; and progressive disease [PD]) was measured in profiled patients with MM with a focus on NAPRT expression: patients achieving at least PR after HDM carried overlapping profiling with FK866-sensitive cells with lower NAPRT mRNA levels than others. In panels A-B,D a representative experiment of 2 was shown as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Unpaired t test was used for panels A,F (∗P ≤ .05).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/5/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024013425/5/m_blooda_adv-2024-013425-gr6.jpeg?Expires=1765897357&Signature=NW4m7UYX3n0hcZKLfTn1~mFNm2lpts3X6iZh9Wjs2EuL5FjmaXmxrxqVqD~fbEzvnnW4NdfumbJTbH-zxETo6Kyi2KyB6gdoLezYDL~GXQ3C3nSL8-jV2G5D5BZZA7MzzQZAvtjYGgmElz9Z-eUoRiPjvXI0zm4zJq4~PUyDNvb1s70g6OTpZJ1knkjNuJx07WUyu5F1p3mvpZgA4hJIJ-K8QpVX0Epykt72oKxaFDdgCMzG7Du8svMauTohpuhi3XFXLXxXKovRNKAuAgBpc9vVzPuW~mEhxE-j1ryccD~jO5bpVISIfuRvmTnjLM5yyFNngCj6rexe1g5NYELQ0w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)