Key Points

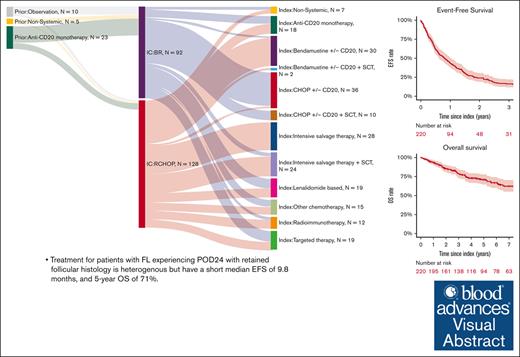

Patients with FL experiencing POD24 with retained follicular histology have a short median EFS of 9.8 months and 5-year OS of 71%.

After POD24, cause of death in patients with FL is predominantly due to lymphoma despite infrequent subsequent transformation events.

Visual Abstract

Progression of disease within 24 months of initial immunochemotherapy (POD24) is a negative prognostic factor for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL). There is no standard treatment after POD24. Assembling an academic-based cohort from the Lymphoma Epidemiology of Outcomes Consortium for Real World Evidence, we evaluated patterns of care and outcomes for 220 patients with FL with POD24 and retained FL histology. Therapy after POD24 was heterogeneous, with no treatment category accounting for >25% of the total. Among patients initially treated with bendamustine-rituximab, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (R-CHOP) was the predominant second-line choice (48%). Among patients initially treated with R-CHOP, aggressive salvage therapy was the predominant second-line choice (38%). Overall response rate to therapy after POD24 was 64% (95% confidence interval [CI], 56-70); complete response rate was 39% (95% CI, 32-46). The median event-free survival for therapy after POD24 was 9.8 months (95% CI, 7.3-12.1); 5-year overall survival (OS) was 71% (95% CI, 65-78). OS was inferior for patients aged >70 years (hazard ratio [HR], 2.31; 95% CI, 1.27-4.20) and those with high-risk FL International Prognostic Index scores at diagnosis (HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.23-3.60). No treatment category stood out with more favorable results. Cause of death was predominantly lymphoma related. Patients with follicular histology at their POD24 event had a low cumulative incidence of transformation (1.1% at 5 years). Our study is among the largest cohorts describing contemporary patterns of care for patients with POD24, providing a focused data set useful for interpreting and designing prospective clinical trials in this population.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the second-most common lymphoma and the most common indolent lymphoma in the United States and Western Europe.1,2 Although outcomes have improved over time and the overall survival (OS) for patients at 10 years after diagnosis is ∼80%,3 lymphoma-related events and lymphoma-related death still constitute a significant risk to patients. Results of the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS) demonstrated that patients with relapse or progression of disease within 24 months of initial immunochemotherapy (POD24) of frontline immunochemotherapy (IC) had a 5-year OS of 50% vs 90% for those without.4 Data from the Follicular Lymphoma Analysis of Surrogate Hypothesis, which included multiple international randomized clinical trials with heterogeneous treatments, similarly validated POD24 as a clinical end point of importance and redemonstrated its association with early mortality.5 Efforts to better identify patients at risk of POD24 and mitigation strategies are areas of ongoing research efforts.6-9

Treatment of patients with retained follicular histology at POD24 constitutes a specific clinical challenge. Although guidelines are available for relapsed FL, there is no established standard of care. Specific guidelines for the treatment of POD24 are based on modest available evidence and expert opinion.10 Recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network address refractory disease but not specifically POD24 in their treatment algorithms, with mention of treatment with anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy based on recently published data in this population.11-13 European guidelines similarly lack established standards, with consideration of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in those eligible.14 These diverse recommendations underscore a lack of consensus regarding the optimal therapy for this patient subset, which has historically relied on post hoc analyses of outcomes for subgroups with POD24.

The Lymphoma Epidemiology of Outcomes (LEO) Consortium for Real World Evidence database included a large multicenter US cohort of relapsed or refractory FL, including patients from the LEO Cohort study (NCT02736357) and LEO-participating institutions.15,16 This analysis uses the LEO Consortium for Real World Evidence database to address what therapeutic choices are made in patients with FL after POD24 in contemporary academic practices and what outcomes are observed.

Methods

Patients with POD24 FL were identified at 8 academic centers in the United States participating in the LEO Cohort study (NCT02736357; https://leocohort.org/): Cornell University, Emory University, Mayo Clinic Rochester, MD Anderson, University of Iowa, University of Miami, University of Rochester, and Washington University in St Louis. Patients included in this analysis were enrolled in the prospective LEO Cohort study, the prospective University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence Molecular Epidemiology Resource, or identified from the institutional databases at each LEO Center.15-17 Clinical data, including details at each line of therapy, were abstracted from medical records into a central database maintained by the LEO Cohort Biostatistics and Informatics Core. All pathology at diagnosis was confirmed by expert lymphoma clinicians or hematopathologists at each center, and pathology reports at relapse were clinician reviewed. All management decisions for those not on a clinical trial protocol were per the practice of the treating physicians. This study was approved by a centralized institutional review board coordinated at the Mayo Clinic.

Inclusion criteria identified patients initially diagnosed with biopsy-proven FL grade 1 to 3A between 15 February 2002 and 11 December 2019 who received an initial course of IC. We defined IC as either “BR” (bendamustine + anti-CD20 antibody [rituximab (R)] or obinutuzumab) or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (R-CHOP) (anti-CD20 antibody + cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). Patients under observation or receiving radiation or anti-CD20 antibody monotherapy before initial IC were included to create a more inclusive definition similar to other large databases and the SWOG 1608 trial (NCT03269669). All patients had POD24 as defined by nonresponse, progression, or change in treatment due to inefficacy within 24 months of the beginning of IC and initiated subsequent therapy after POD24. Patients with biopsy-proven transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or FL grade 3B at the time of POD24 (n = 56) were excluded from the study.

The index therapy was defined as the first treatment after initial IC. Therapeutic groups were generated to reflect similar characteristics and/or frequency of a diverse number of regimens and agent types. “BR” and “R-CHOP” represented regimens as detailed for IC categories. “Intensive salvage” regimens described multiagent, dose-dense, highly myelosuppressive combinations that almost always included a platinum or ifosfamide. “Lenalidomide-based” was defined as any lenalidomide-containing regimen unless including R-CHOP, BR, or intensive salvage combinations. Regimens not meeting above criteria and including agents such as those targeting Bruton tyrosine kinase, CD137, CD47, immune checkpoints, histone de acetylase, interleukin-15, interleukin-2, JAK2, PI3K, or the proteasome were grouped as “targeted therapies.” Anti-CD20 monotherapy and radioimmunotherapy were each grouped separately. All other systemic therapies were grouped as “other chemotherapy.” Clinical trial participants were grouped by the treatment they received when known.

The principal end points of interest were event-free survival (EFS) and OS. Other end points were overall response rate (ORR), complete response rate (CRR), and duration of response (DOR). Responses were assessed via Lugano or Cheson criteria by positron emission tomography (PET) scan, computed tomography (CT) scan, and/or by clinician assessment. EFS was defined as the time from initiation of index therapy to the first progression, relapse, transformation, initiation of a new line of treatment for lack of efficacy, or death from any cause. DOR was defined as the time from the date of first response on index therapy to progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from initiation of index therapy to death from any cause.

Time-to-event variables were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between subgroups were evaluated using an unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model. Transformation was modeled as a cumulative incidence with death as a competing risk; causes of death were modeled using a competing risk approach. Cause of death was determined via a review of death certificate copy and/or medical records using a standard protocol and classified as the result of lymphoma (progression or transformation), treatment, unrelated cancer, other causes, or unknown. Treatment-related mortality was broadly defined and further classified into infection, cardiac, or secondary malignancy (myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia). All analyses used complete case data on all eligible patients. Numbers of patients in subsets and/or with missing data for analysis variables are provided in results tables. All models and results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P values are not reported because there were no formal hypotheses tested. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding patients who received nonsystemic or R-monotherapy before IC and following the original NLCS definition of POD24 (event within 24 months of diagnosis and IC within 6 months of diagnosis).4 All analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2).

Results

Clinical characteristics at diagnosis

A total of 220 patients were identified who received treatment for POD24 after first-line R-CHOP or BR (174 from the prospective LEO Cohort and 46 from retrospective augmentation; supplemental Figure 1). The median age of patients at diagnosis was 56 years (range, 23-81; interquartile range [IQR], 48-64). Most patients were male (n = 128 [59%]), White (n = 174 [79%]), and had an initial stage of III to IV (92%). Histologic grade at diagnosis was 1 to 2 in 81% and 3A in 15%. More patients had high- (50%) and intermediate-risk (33%) FL International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) scores than low-risk scores (17%). Bone marrow involvement was seen in 59% of patients with bone marrow assessments (Table 1).

Patient characteristics at diagnosis and index therapy

| . | At diagnosis (N = 220) . | At index therapy (N = 220) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 56 (48-64) | 58 (49-66) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 128 (58%) | — |

| Female | 92 (42%) | — |

| Race | ||

| White | 174 (79%) | — |

| African American | 8 (4%) | — |

| Other | 11 (5%) | — |

| Unknown | 27 (12%) | — |

| Stage | ||

| I-II | 16 (8%) | 21 (12%) |

| III-IV | 182 (92%) | 161 (88%) |

| Missing | 22 | 38 |

| Histologic grade | ||

| Grade 1-2 | 177 (80%) | 161 (73%) |

| Grade 3A | 32 (15%) | 39 (18%) |

| Unknown 1-3A | 11 (5%) | 20 (9%) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2002-2010 | 87 (40%) | — |

| 2011-2020 | 133 (60%) | — |

| Eastern cooperative group PS | ||

| 0-1 | 136 (92%) | 155 (97%) |

| 2-4 | 12 (8%) | 4 (3%) |

| Missing | 72 | 61 |

| B symptoms | ||

| None reported | 219 (86%) | 245 (96%) |

| Yes | 37 (14%) | 11 (4%) |

| Lactated dehydrogenase | ||

| Not elevated | 83 (61%) | 92 (68%) |

| Elevated | 53 (39%) | 44 (32%) |

| Missing | 84 | 84 |

| Hemoglobin | ||

| <12 | 35 (25%) | 35 (23%) |

| >12 | 106 (75%) | 120 (77%) |

| Missing | 79 | 65 |

| Number of nodal groups | ||

| 0-4 | 68 (37%) | 110 (60%) |

| >4 | 115 (63%) | 72 (40%) |

| Missing | 37 | 38 |

| Bulky disease | ||

| No | 119 (72%) | 135 (85%) |

| Yes | 46 (28%) | 24 (15%) |

| Missing | 55 | 61 |

| Bone marrow involvement | ||

| Yes | 105 (59%) | 38 (29%) |

| No | 73 (41%) | 93 (71%) |

| Missing | 42 | 89 |

| FLIPI | ||

| 0-1 | 24 (17%) | 34 (26%) |

| 2 | 46 (33%) | 46 (35%) |

| 3-5 | 69 (50%) | 51 (39%) |

| Missing | 81 | 89 |

| GELF criteria | ||

| ≥1 GELF criteria | 100 (45%) | 74 (34%) |

| No reported GELF criteria | 120 (55%) | 146 (66%) |

| Treatment location | ||

| LEO Center | 91 (43%) | 124 (58%) |

| Other center | 122 (57%) | 91 (42%) |

| Missing | 7 | 5 |

| Clinical trial status | ||

| Treated on trial | 7 (3%) | 40 (19%) |

| Not on trial | 199 (97%) | 169 (81%) |

| Missing | 14 | 11 |

| . | At diagnosis (N = 220) . | At index therapy (N = 220) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 56 (48-64) | 58 (49-66) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 128 (58%) | — |

| Female | 92 (42%) | — |

| Race | ||

| White | 174 (79%) | — |

| African American | 8 (4%) | — |

| Other | 11 (5%) | — |

| Unknown | 27 (12%) | — |

| Stage | ||

| I-II | 16 (8%) | 21 (12%) |

| III-IV | 182 (92%) | 161 (88%) |

| Missing | 22 | 38 |

| Histologic grade | ||

| Grade 1-2 | 177 (80%) | 161 (73%) |

| Grade 3A | 32 (15%) | 39 (18%) |

| Unknown 1-3A | 11 (5%) | 20 (9%) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2002-2010 | 87 (40%) | — |

| 2011-2020 | 133 (60%) | — |

| Eastern cooperative group PS | ||

| 0-1 | 136 (92%) | 155 (97%) |

| 2-4 | 12 (8%) | 4 (3%) |

| Missing | 72 | 61 |

| B symptoms | ||

| None reported | 219 (86%) | 245 (96%) |

| Yes | 37 (14%) | 11 (4%) |

| Lactated dehydrogenase | ||

| Not elevated | 83 (61%) | 92 (68%) |

| Elevated | 53 (39%) | 44 (32%) |

| Missing | 84 | 84 |

| Hemoglobin | ||

| <12 | 35 (25%) | 35 (23%) |

| >12 | 106 (75%) | 120 (77%) |

| Missing | 79 | 65 |

| Number of nodal groups | ||

| 0-4 | 68 (37%) | 110 (60%) |

| >4 | 115 (63%) | 72 (40%) |

| Missing | 37 | 38 |

| Bulky disease | ||

| No | 119 (72%) | 135 (85%) |

| Yes | 46 (28%) | 24 (15%) |

| Missing | 55 | 61 |

| Bone marrow involvement | ||

| Yes | 105 (59%) | 38 (29%) |

| No | 73 (41%) | 93 (71%) |

| Missing | 42 | 89 |

| FLIPI | ||

| 0-1 | 24 (17%) | 34 (26%) |

| 2 | 46 (33%) | 46 (35%) |

| 3-5 | 69 (50%) | 51 (39%) |

| Missing | 81 | 89 |

| GELF criteria | ||

| ≥1 GELF criteria | 100 (45%) | 74 (34%) |

| No reported GELF criteria | 120 (55%) | 146 (66%) |

| Treatment location | ||

| LEO Center | 91 (43%) | 124 (58%) |

| Other center | 122 (57%) | 91 (42%) |

| Missing | 7 | 5 |

| Clinical trial status | ||

| Treated on trial | 7 (3%) | 40 (19%) |

| Not on trial | 199 (97%) | 169 (81%) |

| Missing | 14 | 11 |

GELF, Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires.

First-line IC treatment characteristics

The median time from diagnosis to first-line IC was 1 month (IQR, 0.5-4.4). Thirty-eight patients (17%) received select prior therapy or were observed before initiating IC, including 23 patients receiving anti-CD20 monotherapy, 5 patients receiving nonsystemic therapy such as radiation, and 10 patients who were observed. A total of 128 patients (58%) received R-CHOP, and 92 patients (42%) received BR. Patients treated with IC through 2009 (n = 50) were exclusively treated with R-CHOP, whereas BR was more common (n = 91 [59%]) in patients treated in or after 2011. Patients who received R-CHOP were younger than those who received BR (median age, 53 vs 62 years, respectively). There was a slight male predominance in both treatment groups (R-CHOP, 56%; BR, 61%). More patients with FL 3A were treated with R-CHOP (n = 29 [81%]) than BR (n = 7 [19%]). Patients receiving R-CHOP had a higher Eastern cooperative group performance status (PS; Eastern cooperative group PS 2-4, 11% vs 3% for those with BR). Sixty-two percent of patients receiving BR had high-risk FLIPI compared with 46% of patients receiving R-CHOP (Table 1). POD24 was defined by progression on imaging in 86% of patients (PET 50%, CT 35%, and other imaging 1%), change in treatment in 2%, clinical assessment as progression in 2%, and was not listed in 10%.

Patient characteristics at index therapy after POD24

Characteristics at index therapy after POD24 were broadly similar to diagnosis and frontline IC (Table 1). The median age at index therapy was 58 years (range, 27-93; IQR, 49-66). One hundred forty-six patients (66%) underwent biopsy before index therapy, as did all 56 patients excluded for transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or FL grade 3B at the time of POD24. Histologic grade remained predominantly grade 1 to 2 in 73% vs 17% with grade 3A. Stage, ECOG PS, and incidence of elevated lactated dehydrogenase were generally similar between diagnosis and the time of index therapy (Table 1).

The median time from initiation of BR/R-CHOP to index treatment was 14 months (range, 1.4-42.8; IQR, 9-20.7); this did not differ significantly between patients who received R-CHOP (13 months) vs BR (16 months).

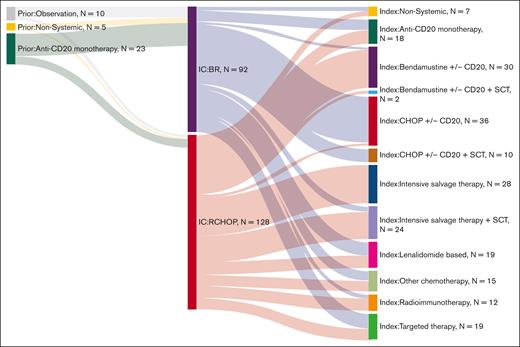

Patterns of index treatment after POD24

Index therapy after POD24 (initiated between June 2003 and April 2022) was heterogeneous, with no treatment strategy applied to more than a quarter of patients, and 19% of patients received therapy as part of a clinical trial. The most frequent therapeutic strategies at index therapy were intensive salvage chemotherapy (n = 52 [24%]), R-CHOP (n = 46 [21%]), and BR (n = 32 [15%]; Figure 1). Nineteen patients (9%) were treated with targeted agents, of whom 5 patients received PI3Ki. Lenalidomide-based therapy was used in 19 patients (9%). Anti-CD20 monotherapy was used in 18 patients (8%). Other less frequent choices are depicted in Figure 1.

The most frequent treatment at POD24 for patients who received R-CHOP in first line was intensive salvage chemotherapy ± hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT; n = 48), followed by BR (n = 30) and anti-CD20 monotherapy (n = 10). The most frequent treatment at POD24 for patients who received BR in first line was R-CHOP (n = 44), followed by targeted therapies (n = 11) and lenalidomide-based therapy (n = 10; Figure 1). Over the study period, 61 patients (28%) received HSCT, and 17 patients (8%) received CAR-T therapy at any time after the index line.

In total, 16% of all patients (n = 36) underwent HSCT as part of index therapy: 32 underwent ASCT, 3 underwent allogeneic transplants, and 1 HSCT was unclassified. Of 128 patients who had first-line R-CHOP, 48 (38%) proceeded to salvage chemotherapy, but only 20 of these received ASCT. Two patients received BR after R-CHOP and underwent consolidation with ASCT (Figure 1). Interestingly, only 4 patients who had BR in the first line had salvage therapy as index therapy, with all 4 undergoing ASCT consolidation; most patients who had frontline BR and underwent ASCT in later lines had R-CHOP before transplant (n = 10).

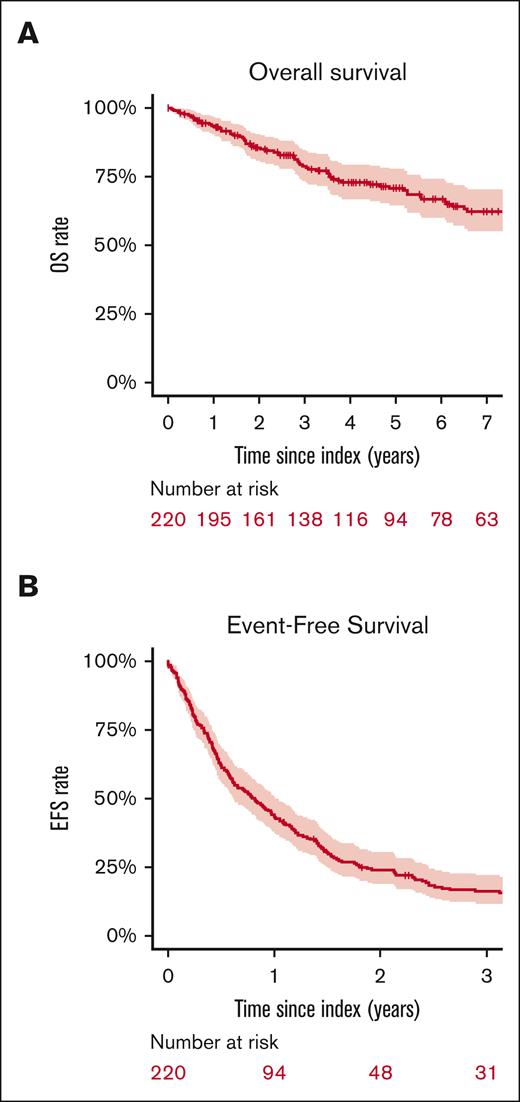

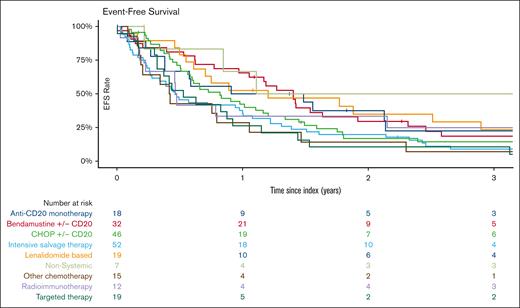

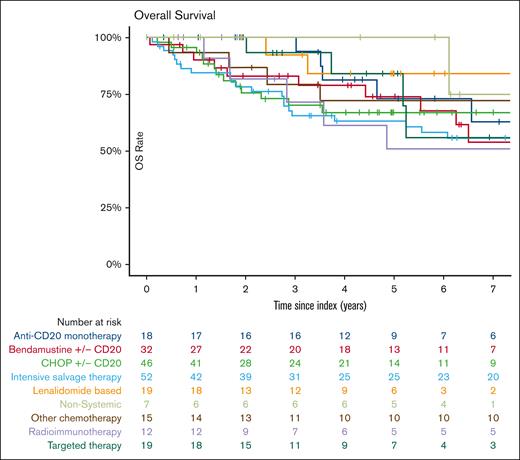

Survival outcomes after POD24

With a median follow-up of 62 months (IQR, 57-105), the median EFS after treatment for POD24 was 9.8 months (95% CI, 7.3-12.1). EFS was 24% (95% CI, 19-31) at 2 years and 12% (95% CI, 9-18) at 5 years (Figure 2). EFS did not significantly vary with index treatment, with the exceptions of “other chemotherapy” regimens (median EFS, 5.4 months [95% CI, 2.8-27.6]; hazard ratio [HR], 1.9 [95% CI, 1.1-3.3] vs BR/R-CHOP) and intensive salvage therapy (median EFS, 5.5 months [95% CI, 3.4-12]; HR, 1.49 [95% CI 1.02-2.2] vs BR/R-CHOP) (Table 2, Figures 3 and 4). No difference in EFS was seen based on age groups (18-59 vs 60-69 vs 70+ years), gender, historical cohort (2002-2010 vs 2011-2020), first-line IC regimen, FLIPI at diagnosis (FLIPI 0-1 vs FLIPI 2; FLIPI 0-1 vs FLIPI 3-5), or clinical trial participation.

Outcomes at index therapy by index treatment

| Treatment group . | N . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All treatments | 220 | 100 | 24% (19-30) | 71% (64-78) |

| Anti-CD20 monotherapy | 18 | 8 | 37% (20-69) | 73% (53-100) |

| Bendamustine ± CD20 | 32 | 15 | 30% (17-51) | 74% (59-93) |

| CHOP ± CD20 | 46 | 21 | 17% (9-33) | 67% (54-84) |

| Intensive salvage therapy | 52 | 24 | 20% (11-35) | 63% (51-78) |

| Lenalidomide based | 19 | 9 | 35% (19-66) | 84% (66-100) |

| Nonsystemic | 7 | 3 | 50% (22-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Other chemotherapy | 15 | 7 | 14% (4-52) | 72% (52-100) |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 12 | 5 | 33% (15-74) | 51% (28-94) |

| Targeted therapy | 19 | 9 | 11% (3-39) | 84% (66-100) |

| Treatment group . | N . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All treatments | 220 | 100 | 24% (19-30) | 71% (64-78) |

| Anti-CD20 monotherapy | 18 | 8 | 37% (20-69) | 73% (53-100) |

| Bendamustine ± CD20 | 32 | 15 | 30% (17-51) | 74% (59-93) |

| CHOP ± CD20 | 46 | 21 | 17% (9-33) | 67% (54-84) |

| Intensive salvage therapy | 52 | 24 | 20% (11-35) | 63% (51-78) |

| Lenalidomide based | 19 | 9 | 35% (19-66) | 84% (66-100) |

| Nonsystemic | 7 | 3 | 50% (22-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Other chemotherapy | 15 | 7 | 14% (4-52) | 72% (52-100) |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 12 | 5 | 33% (15-74) | 51% (28-94) |

| Targeted therapy | 19 | 9 | 11% (3-39) | 84% (66-100) |

At the time of data cutoff (3 November 2023), 71 patients had died (32%). OS was 86% (95% CI, 81-91) at 2 years and 71% (95% CI, 65-78) at 5 years. OS did not vary either by first-line IC regimen, historical cohort or index treatment regimen, or clinical trial participation. Age ≥70 years at diagnosis was associated with inferior OS (HR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.3-4.4), compared with age 18 to 59 years, as was high-risk FLIPI (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2-3.5) compared with low-risk FLIPI. Further comparisons are detailed in Table 3 and supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Among the 36 patients who ultimately underwent transplant consolidation after index treatment, the median EFS from transplant was 14.4 months (95% CI, 10.0-25.1), the 2-year EFS was 37% (95% CI, 24-58), and the 5-year OS was 68% (95% CI, 54-87).

Outcomes at index therapy by index treatment subset by 1L IC

| Treatment group . | BR . | R-CHOP . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . | n . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . | |

| All treatments | 92 | 100 | 20% (13-31) | 66% (56-79) | 128 | 100 | 26% (20-35) | 73% (66-82) |

| Anti-CD20 monotherapy | 8 | 9 | 31% (10-96) | 54% (26-100) | 10 | 8 | 40% (19-85) | 89% (71-100) |

| Bendamustine ± CD20 | 2 | 2 | 0% (NA to NA) | 100% (100-100) | 30 | 23 | 32% (19-54) | 72% (56-93) |

| CHOP ± CD20 | 44 | 48 | 15% (7-31) | 65% (51-83) | 2 | 2 | 50% (13-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Intensive salvage therapy | 4 | 4 | 33% (7-100) | 100% (100-100) | 48 | 38 | 19% (10-34) | 61% (49-77) |

| Lenalidomide based | 10 | 11 | 50% (27-93) | 83% (58-100) | 9 | 7 | 22% (7-75) | 83% (58-100) |

| Nonsystemic | 3 | 3 | 50% (13-100) | 100% (100-100) | 4 | 3 | 50% (19-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Other chemotherapy | 7 | 8 | 0% (NA to NA) | 36% (12-100) | 8 | 6 | 25% (8-83) | 100% (100-100) |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 3 | 3 | 33% (7-100) | 67% (30-100) | 9 | 7 | 33% (13-84) | 50% (25-100) |

| Targeted therapy | 11 | 12 | 9% (1-59) | 70% (42-100) | 8 | 6 | 12% (2-78) | 100% (100-100) |

| Treatment group . | BR . | R-CHOP . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . | n . | % . | 2-year EFS (95% CI) . | 5-year OS (95% CI) . | |

| All treatments | 92 | 100 | 20% (13-31) | 66% (56-79) | 128 | 100 | 26% (20-35) | 73% (66-82) |

| Anti-CD20 monotherapy | 8 | 9 | 31% (10-96) | 54% (26-100) | 10 | 8 | 40% (19-85) | 89% (71-100) |

| Bendamustine ± CD20 | 2 | 2 | 0% (NA to NA) | 100% (100-100) | 30 | 23 | 32% (19-54) | 72% (56-93) |

| CHOP ± CD20 | 44 | 48 | 15% (7-31) | 65% (51-83) | 2 | 2 | 50% (13-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Intensive salvage therapy | 4 | 4 | 33% (7-100) | 100% (100-100) | 48 | 38 | 19% (10-34) | 61% (49-77) |

| Lenalidomide based | 10 | 11 | 50% (27-93) | 83% (58-100) | 9 | 7 | 22% (7-75) | 83% (58-100) |

| Nonsystemic | 3 | 3 | 50% (13-100) | 100% (100-100) | 4 | 3 | 50% (19-100) | 100% (100-100) |

| Other chemotherapy | 7 | 8 | 0% (NA to NA) | 36% (12-100) | 8 | 6 | 25% (8-83) | 100% (100-100) |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 3 | 3 | 33% (7-100) | 67% (30-100) | 9 | 7 | 33% (13-84) | 50% (25-100) |

| Targeted therapy | 11 | 12 | 9% (1-59) | 70% (42-100) | 8 | 6 | 12% (2-78) | 100% (100-100) |

1L, first line; NA, not available.

The cause of death was primarily progressive lymphoma (54%), followed by complications of therapy (14%), secondary malignancies (3%), and other causes (10%). Causes of death were unable to be determined for 20% cases. The 5-year incidence of all lymphoma-related deaths was 21% (95% CI, 16-28), and the 5-year incidence of all non–lymphoma-related deaths was 2% (95% CI, 0.8-5.7; supplemental Figure 3).

Treatment response and histologic transformation after POD24

ORR for any treatment was 64% (95% CI, 56-70). CRR for any treatment was 39% (95% CI, 32-46). DOR at 2 years was 34% (95% CI, 26-45). Outcomes from index therapy by therapeutic class are displayed in supplemental Table 1. One hundred ninety-six patients (89%) received at least 1 subsequent line of treatment after index therapy.

Histologic transformations occurring after POD24 were uncommon, with only 4 patients having a documented transformation event during follow-up and a 5-year cumulative incidence of transformation of 1.1% (95% CI, 0.3-4.5; supplemental Figure 2).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis using the original NLCS definition of POD24 was performed with 165 patients meeting the inclusion criteria (event within 24 months of diagnosis and IC within 6 months of diagnosis, excluding treatment before IC).4 Demographics and baseline data did not differ between the primary and sensitivity analyses. The median time from diagnosis to POD24 event was 15 months (IQR, 9.3-21.4). Sixty-eight percent of patients received R-CHOP, and 32% of patients received BR as frontline IC. Intensive salvage therapy ± ASCT was the most frequent POD24 treatment, used in 46 patients (28%), followed by R-CHOP in 31 (19%) and BR in 24 (15%). Transplant consolidation was performed in 27 patients (16%) as part of index therapy. Considering all subsequent lines of therapy, ASCT was used in 32% (n = 52), and 9% (n = 15) received CAR-T therapy by the study cutoff. With a median follow-up of 62 months, the median EFS was 9.5 months (95% CI, 7-12). EFS at 2 years was 22% (95% CI, 17-30). The 5-year OS was 71% (95% CI, 64-79; supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

We report one of the largest multicenter data sets on the patterns of care and outcomes for patients with POD24 FL retaining follicular histology in the current era. We identified that therapy for FL in US academic settings is heterogeneous, with frequent incorporation of aggressive strategies. We also found that the median EFS for therapy after POD24 was only 9.8 months, setting an important contemporary benchmark for outcomes in this group. The 5-year OS was 71%. OS was inferior for older patients and those with high-risk FLIPI scores at diagnosis. Among patients who died, the cause of death was predominantly (88% of known causes) related to lymphoma. Patients with retained follicular histology at their POD24 event had a low cumulative incidence of subsequent transformation (1.1% at 5 years). These findings confirm that early events after IC portend a poor prognosis even in the absence of transformation.

There is no consensus on the standard of care for POD24 FL, and there is a paucity of data on which to build evidence-based recommendations. A 2019 expert recommendation suggested clinical trial options, which was used in 19% of our cohort, resulting in no clinically or statistically significant difference in survival or response rates in our participants.10 Other recommendations include consideration of anti-CD20 antibody and CHOP or bendamustine, depending which was used as first line, followed by consideration of ASCT in those who are transplant eligible. For those not eligible for transplant, consideration of lenalidomide combined with anti-CD20 antibodies, among other options, have also been proposed. However, most recommendations are based on expert consensus from retrospective studies and subset analyses of prospective trials in the absence of clinical trial results specifically focused on the POD24 population.10

Second-line therapies for FL reported in comparative effectiveness literature most commonly report utilization of BR, R-monotherapy, ASCT, R-CHOP, and other R-chemotherapy regimens, but these lack specificity for POD24 patients.16,18 POD24 patients were evaluated in a subset analysis of the NLCS, which, in contrast to our study, was mostly based in the community setting rather than academic centers.19 Patients in our study were much less likely to receive R-monotherapy at index after POD24 (30% NLCS vs 8% in our cohort) and R-alkylator regimens (∼20% vs 15%) and were more likely to receive nonapproved agents on a clinical trial (4.4% vs 9%), anthracyclines (18% vs 21%), and HSCT (3.5% vs 16%), reflecting the patient heterogeneity of our cohort.19

Practice patterns in our cohort commonly used traditional chemotherapy as the next treatment for patients with POD24. It is important to recognize that the practice patterns represent an aggregate of treatments over 2 decades and do not constitute a contemporary snapshot of current strategies; this may underestimate the degree to which other, newer agents may be used. Immunomodulatory regimens containing lenalidomide, although not available throughout the entirety of the study cohort era, represented 9% of choices in our cohort. Use of targeted therapies such as Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, checkpoint inhibitors, histone de acetylase inhibitors, or other investigational agents was insufficiently frequent to result in informative outcomes. In this cohort, the frequent utilization of intensive salvage therapy, most notably after R-CHOP, differs from its utilization in an unselected post-IC relapse population.16

We found that the median EFS after POD24 treatment was very low at 9.8 months. Transient EFS has been reported for POD24 patient subsets in many clinical trials and observational studies, which report progression free survival or EFS ranging from 5.6 to 30.4 months for noncellular therapy. Most patients have an event or progression within 2 years of second-line therapy, with DOR of ∼12 to 15 months.19-31 With no standard treatment strategy for patients after POD24 and no strong evidence of improved results for those treated in the past 10 years, our results support efforts to develop novel treatment modalities, such as cellular therapies or bispecific antibodies, to improve outcomes for this patient population, moving them to earlier lines of therapy. For instance, phase 2 studies with CAR-Ts showed a median progression free survival of 40 months (axicabtagene ciloleucel) and 36 months (tisagenleleucel) in subsets of patients with at least 2 prior lines of therapy and a history of POD24, respectively.32,33 In a similar trial subpopulation, epcoritamab represented the potential of bispecific antibodies, with ORR and CRR of 80% and 61%, respectively.34 Further evaluations of cellular therapies are underway, such as the ZUMA-22 study (NCT05371093), which randomizes high-risk relapsed/refractory patients with FL enriched for POD24 to axicabtagene ciloleucel vs standard-of-care regimens.35

Since the sentinel report in 2015 describing 5-year OS of 50% after early relapse of FL, POD24 has continued to be validated as an important predictor of poor long-term outcomes and informs a priority objective in the global strategy for clinical research in FL.4,36,37 The 5-year OS in our study of 71% was consistent with the pooled clinical trial cohort data from Follicular Lymphoma Analysis of Surrogate Hypothesis, which showed a 5-year OS of 71.2% in >1500 patients with FL with POD24 after chemotherapy, rituximab, or both.38 Eighty-five POD24 patients pooled from 3 Swiss SAKK trials using nonchemotherapy regimens experienced a 5-year OS of 69%.39 The German Low Grade Lymphoma Study group analyzed 113 POD24 patients from 2 trials using induction chemotherapy with or without rituximab and showed a 5-year OS of 77% for those with second-line ASCT and 59% for those who did not undergo ASCT.31 The patients in this cohort who underwent transplant had a 5-year OS of 68% (95% CI, 54-87). Comparisons across reports are challenging because our cohort was exclusively treated in the first line with IC and excluded POD24 transformation events, with a high rate of biopsy. Our cohort had a more inclusive definition of POD24, allowing for R-monotherapy, nonsystemic therapy, and observed patients; however, our sensitivity analysis using the original (stricter) definition of POD24 from NLCS still showed a 5-year OS of 71%.

Our cohort with evaluation of patients with only retained follicular histology is consistent with many clinical trials but may differ from previous observational studies that included patients with transformed disease as the early event.13,20-28 On the GALLIUM trial investigating obinutuzumab-based frontline therapy, patients who had POD24 with transformed histology had a 2-year OS of ∼48%, compared with 73% for those without transformation.40 However, only 15% of patients were biopsied at first progression in GALLIUM. In an observational cohort of 328 patients with transformed FL, the 2-year OS was 54% for patients with transformation within 2 years after starting IC.41

With similar OS and uniformly short EFS across described subpopulations, POD24 FL likely represents a unique biology. Previous reports have linked early relapse after IC to anomalies in the tumor microenvironment or T-follicular helper cells.7,8 Additional efforts are ongoing to evaluate genetic and epigenetic markers that may predict POD24. Genetic panels such as CCP-32 were able to predict a poor-outcome group with an observed POD24 phenotype of 56%, compared with samples with a predicted good outcome having only 18% incidence of POD24. Although imperfect, these studies provide emerging evidence of underlying biologic differences that drive POD24.42

Many clinical trials in POD24 FL lack maturity to report 5-year survival, and therefore outcomes focus on ORR and complete response. Reported treatment responses in patients with POD24 FL have significant heterogeneity, with ORRs ranging from 33% to 93% and CRRs as low as 12% to as high as 72% with CAR-T.12,13,24,43,44 Our study is consistent with previous noncellular therapy findings, with ORR of 64% and CRR of 39% . However, in this retrospective study, response assessments were not conducted at standardized time points or subject to central review, and they comprised heterogeneous strategies inclusive of PET, CT, and clinical assessment; thus, the accuracy of response assessments in this study is potentially lower than what is obtained from clinical trials.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is strengthened by the use of a sensitivity analysis that showed similar EFS and OS using the more stringent definition by NLCS, which excluded observation or other forms of treatment. Our current definition may also differ from other observational studies or clinical trials.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The retrospective observational nature does not allow for conclusions or comparisons of therapies due to uncontrolled selection bias. The practice patterns likely contain selection bias based on the academic practices of the LEO Consortium. The study’s findings, therefore, may not be reflective of “real-world” data. The time period selected for this study is too early to account for the routine use of bispecific antibodies and CAR-Ts, because these are only currently approved after ≥2 lines of therapy. We include ASCT use in the description of patterns of care but did not consider ASCT as a treatment group due to inherent time-dependent biases of getting to ASCT.

The data presented fill an important knowledge gap regarding practice patterns and subsequent outcomes in patients with POD24 FL. Although multiple options exist for relapsed/refractory FL, these data demonstrate that there is no clearly superior approach for treating patients at POD24. The data from this study will also help provide critical context for clinical trial results, and researchers may be able to use the data when designing future clinical trials. The data presented here also serve as a reminder that although 5-year OS is ∼70% in POD24 with retaining follicular histology, patients’ journeys with this disease are marked by limited DORs, and lymphoma-related mortality rates remain high. With such frequent and multiple relapses, novel therapies with longer response duration are critically needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Cancer Institute (Lymphoma Epidemiology of Outcomes U01CA195568 and University of Iowa/Mayo Clinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence P50CA097274) and the Lymphoma Research Foundation (Jaime Peykoff Follicular Lymphoma Initiative Priority Research grant). J.R.D.’s efforts on the project were supported by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant Iowa Stimulating Access to Research in Residency Scholars Program (R38 HL150208).

Authorship

Contribution: J.R.D., M.C.L., B.K.L., M.J.M., and C.C. contributed to conception and/or design of the study/research; J.R.D., M.C.L., U.D., T.M.H., I.S.L., Y.W., L.J.N., C.S., D.C., P.M., J.P.L., J.B.C., B.S.K., J.R., W.R.B., J.L.K., J.W.F., J.R.C., C.R.F., B.K.L., M.J.M., and C.C. contributed to collection and/or assembly of the data; J.R.D., M.C.L., U.D., T.M.H., I.S.L., Y.W., L.J.N., C.S., D.C., P.M., J.B.C., B.S.K., J.R., W.R.B., J.L.K., J.W.F., J.R.C., C.R.F., B.K.L., M.J.M., and C.C. contributed to analysis and/or interpretation of the data; J.R.D., M.C.L., B.K.L., M.J.M., and C.C. drafted the manuscript; and all authors provided the final approval for the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.W. reports research funding from LOXO Oncology, Novartis, MorphoSys, Innocare, Incyte, Genentech, Eli Lilly, and Genmab; membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for LOXO Oncology, TG Therapeutics, Innocare, Incyte, Eli Lilly, BeiGene, Kite, Janssen, and AstraZeneca; consultancy fees from Innocare and AbbVie; and honoraria from Kite. L.J.N. reports honoraria from Gilead Sciences/Kite Pharma, AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Genentech, Inc, Genmab, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Takeda, AbbVie, Daiichi Sankyo, DeNovo, Caribou Biosciences, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, and ADC Therapeutics; and research funding from Gilead Sciences/Kite Pharma, Genentech, Inc, Genmab, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, Caribou Biosciences, and Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene. P.M. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Epizyme, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Pepromene, and Daiichi Sankyo. I.S.L. reports membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Lymphoma Research Foundation; research funding from the National Cancer Institute; honoraria from Adaptive; current employment with University of Miami; and consultancy fees from BeiGene. J.R.C. reports research funding from Genmab, Bristol Myers Squibb, NanoString, and Genentech; membership on an entity's board of directors or advisory committees for Bristol Myers Squibb; and safety monitoring committee fees from Protagonist. C.R.F. reports consultancy fees from BeiGene, N-Power Medicine, Genentech Roche, SeaGen, Bayer, AbbVie, Genmab, Gilead, Spectrum, Pharmacyclics Jansen, Karyopharm, Denovo Biopharma, and Foresight Diagnostics; research funding from 4D, MorphoSys, Genentech Roche, Acerta, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, AbbVie, Gilead, Pfizer, Nektar, Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, Takeda, Guardant, Iovance, Kite, Celgene, Novartis, Ziopharm, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, National Cancer Institute, V Foundation, Adaptimmune, Allogene, TG Therapeutics, Xencor, CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research, Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas, Amgen, and Cellectis; and is a current holder of stock options in a privately held company in N-Power Medicine and Foresight Diagnostics. C.C. reports research funding from SecuraBio, GenMab, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Verastem, and Genentech; consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Genentech; and leadership role fees from Follicular Lymphoma Foundation. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Carla Casulo, Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642; email: carla_casulo@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

Author notes

J.R.D. and M.C.L. contributed equally to this study and are joint first authors.

M.J.M. and C.C. contributed equally to this study and are joint senior authors.

Data sharing policies and the process to request LEO data that support the findings of this study can be found on the LEO Cohort website (https://leocohort.org/). The data are not publicly available.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.