Key Points

The FL24Cx is an assay that can, before treatment, identify patients with FL at high risk for progression or death.

The FL24Cx was rigorously developed and independently validated to predict EFS24 in pretreatment formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies.

Visual Abstract

Although follicular lymphoma (FL) typically follows an indolent course, patients with FL who experience early events, such as transformation or progression, have increased risk of death related to lymphoma. The FL24Cx is an algorithm based on a 45-target gene expression profiling (GEP) assay, which was developed and trained using 265 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples on a reliable platform to predict, at the time of diagnosis, whether a patient will experience an event within 24 months. The modeling also confirmed and relied upon previously reported synergy between immune response (IR) gene expression signatures IR1 and IR2. Once locked, the 5-factor logistic regression FL24Cx model was independently validated in a retrospectively assessed cohort of 232 patients from 2 immunochemotherapy-treated arms of SWOG Cancer Research Network S0016 phase 3 clinical trial, in which it assigned 169 patients to the low-risk group with 29 events before 24 months (17.2%) and 63 patients to the high-risk group with 24 events before 24 months (38.1%). The relative risk of an event within 24 months after registration among patients who were classified into the high-risk group relative to patients who were classified into the low-risk group was 2.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.41 to 3.51). An up-front GEP biomarker, such as the FL24Cx, rigorously validated in a clinical laboratory and with a clinically relevant turnaround time, could identify and steer enrollment of patients at high risk for early events in clinical trials, thus enabling timely interpretation of such trials and increasing the pace of innovation.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent lymphoma, accounting for ∼30% of all lymphomas, and has a 10-year overall survival (OS) of ∼80%. However, some patients experience a more aggressive disease course, including early progression of FL or transformation to an aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Asymptomatic and low tumor burden or limited stage patients can initially be managed by observation1 or treated with radiotherapy or rituximab monotherapy. In contrast, symptomatic and high–tumor burden patients, generally defined by Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria,2 are typically managed at diagnosis with immunochemotherapy, systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy combined with an anti-CD20 antibody (such as rituximab or obinutuzumab).3-7 Thus, there is a wide range of approaches to patient management based on clinical risk.8

The most commonly used clinical predictor of poor outcome is the FL International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), which stratifies patient survival risk based on 5 variables: hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, stage, number of nodal sites, and age. Developed in 2004, in the prerituximab era, the FLIPI divides patients into low-, intermediate-, or high-risk groups with variable predicted 5-year OS of 91%, 78%, 53%, respectively; with more contemporary 5-year OS estimates ≥85% for the intermediate and 75% for the high-risk category.9-11 More recently, a subset of patients was identified at highest risk for excess mortality if they experienced progression or relapse events occurring before 24 months after initial chemotherapy. This risk factor is arguably the most powerful predictor of patient outcome, dividing patients into 2 groups with 5-year OS of 90% and 50%.12 However, this parameter cannot be assessed at diagnosis because 24 months need to pass before risk of early events can be assessed. Subsequent studies have defined early events in different ways, by sometimes including or excluding transformation to high-grade lymphoma or death.12-14 Herein, the term event-free survival at 24 months (EFS24) will be used inclusive of all events including recurrence, progression, transformation, or death.

Previously, we developed several lymphoma diagnostic and prognostic gene expression profiling (GEP) assays using the nCounter platform (nanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA) and have demonstrated the platform’s robustness and reproducibility in lymphoid malignancies, even when used with degraded RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues and used in a clinical diagnostic reference laboratory.15-22 Of note, the success rate of GEP-based assays on specimens received from patients with lymphoma in the hospital clinical laboratory has been in excess of 90%, which compares very favorably to sequencing studies using FFPE tissue.21,23

This study was designed to fill a medical void by creating a reproducible assay on a platform with a strong track record of utility in FFPE biopsies that can risk-stratify patients with FL up front when treatment with immunochemotherapy is under consideration. We identified prognostic genes and gene signatures from previous publications, trained a model to predict early progression events using FFPE tissues from a prospective observational cohort study, and then performed independent validation using the locked model in a US Intergroup phase 3 randomized clinical trial. Herein, we describe our approach to creating the 45-gene “FL24Cx” assay to predict EFS24 failure, with the goal that this tool could be incorporated into risk stratification for clinical trial design.

Methods

Patient cohorts

Three groups of previously described patient data and samples were analyzed in this study. Each study group underwent institutional review board protocol submission and approval at their respective institutions in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The training cohort was a combination of 2 groups of samples: FFPE tissues, sister blocks to snap frozen tumor biopsies, previously analyzed using Affymetrix U133 2.0 arrays on frozen tissues by the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project (https://llmpp.nih.gov/lymphoma/), and FFPE tissues or extracted RNA provided by the University of Iowa–Mayo Clinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Lymphoma Molecular Epidemiological Resource (MER).24 The training cohort (n = 265) represented a real-world, population-based patient cohort in which patients received 1 of the following immunochemotherapy treatments: BR (bendamustine with rituximab; n = 44 [20%]), R-CHOP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; with or without rituximab maintenance; n = 112 [50%]), R-CVP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; with or without rituximab maintenance; n = 69 [30%]), and unknown combination (n = 40). The independent validation cohort, in contrast, consisted of FFPE tissues from a standardized phase 3 clinical trial (SWOG S0016) provided by the SWOG Cooperative Group Lymphoma Committee (https://www.swog.org/clinical-trials/s0016; www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00006721). No serial biopsies were available for analysis.

Initial selection of candidate genes

We surveyed the literature, in which extensive discovery work has been documented, for relevant candidate genes and signatures and identified: 66 genes related to immune response (IR; IR1/IR2),25 24 genes related to tumor biology and microenvironment,19,26 9 genes related to T-cell infiltration,27 and 21 housekeeping genes. A comprehensive review of whole transcriptome data from the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project database yielded some of the signatures previously reported, along with a subset of 24 candidate genes describing stromal biology, which were included for a total candidate gene pool of 144 genes (123 target and 21 housekeeping).

Primary end point

EFS24 was defined as a dichotomous end point excluding patients censored with <24 months of follow-up. In early model exploration, we noted that the biology underpinning progression events appeared relevant to deaths, but irrelevant to the few recorded transformation events; thus, for more accurate model building, patients who experienced a transformation event within 24 months (8 patients) were ultimately excluded from the training set. In the SWOG S0016 validation cohort, neither clinical nor histological evaluation for transformation was assessed at first relapse/progression. We therefore included all progression, relapse (which may have included transformation), and death events within 24 months of trial registration.

FFPE expression laboratory analysis

All FFPE tissues were reviewed by an expert lymphoma hematopathologist (L.M.R.) to confirm the diagnosis of FL and, if needed, macrodissected to achieve a minimum tumor content of at least 60%. RNA was extracted using a modified protocol for the XTRACT 16+ (AutoGen, Holliston, MA) or, for smaller biopsies, manually via the All-Prep FFPE DNA/RNA kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and nucleic acid products were quantified using UV-Vis spectrophotometry via Nanodrop One (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Extracted RNA samples were analyzed on the nCounter platform (nanoString Technologies) using 144 custom oligonucleotide probe sets and the Elements XT TagSet chemistry. Gene counts were log2 transformed, and each sample was then normalized by subtracting the average signal of the 21 housekeeping genes, to arrive at final expression measures.

Division of genes into predictive classes

Predictive genes that performed well in FFPE were divided into 5 categories. The first consisted of genes for which high expression had been previously identified with poor prognosis. Most of these were from Huet et al,19 and FOXP1 was also included due to its association with poor prognosis.26 The second group consisted of genes from the Huet et al publication for which high expression was associated with good prognosis. The third group consisted of the genes CD27 and CD28, which had been identified as potentially associated with good prognosis.27 The final 2 groups were genes in the IR1 and IR2 signatures, which had been previously identified as having a synergistic relationship to survival.25 The 21 housekeeping genes used for normalization were excluded from risk analysis.

FL24Cx model training

Multiple model architectures, including Lasso, support vector machines, and random forests, were evaluated using all 123 target genes on the training set. The most accurate model relied on the demonstration that the IR2 signature, while not significant univariately, acted as a refinement on the other signatures. Therefore, its association with survival was viewed in terms of how it added significance and impacted the other signatures. Similarly, the significance of other signatures was assessed in context of the extent to which they added to IR2.

In the first stage of the modeling process, a gene expression signature was generated for each of the 5 gene sets by taking an unweighted average of the expressions of all genes in that set. In the second stage, each gene was associated with its coefficient in a multivariate linear logistic regression model of EFS24 status consisting of that gene and ≥1 of the weighted signature averages. If that gene was not part of the IR2 gene set, then a model consisted of that gene and the unweighted IR2 signature average. If the gene was in the IR2 gene set, then the model consisted of that gene and the 4 unweighted non-IR2 signature averages. Five genes were removed at this stage for having coefficients in the opposite direction of their expected biology. In the third stage, the signature averages were recalculated. However, rather than being unweighted, the signature averages were weighed according to their associated coefficients previously calculated. The final FL24Cx predictor score is the result of a 5-factor logistic regression, wherein each gene set is treated as a factor, fit to the binary EFS24 end point using these weighted signature averages, excluding 73 additional target genes based on nonsignificance and lack of reproducibility within the training set. The maximal Youden statistic28 of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for this score vs EFS24 (supplemental Figure 1) was used to determine the optimal cut point to divide samples into a poor prognosis (“high risk,” likely to have an early event) and good prognosis group (“low risk,” likely to achieve EFS24).

To evaluate the accuracy of this predictor within the training set, we performed 10-fold internal crossvalidation. Briefly, the training set was randomly divided into 10 groups, without replacement. The model was trained using 9 groups, including variable selection, weight calculation, and cut-point identification, and evaluated on the remaining group. This is repeated 10 times, using each group as the validation set once.

Similar to other digital GEP assays, a lower limit quality cutoff was established; samples are called “poor quality” if the geometric mean of the housekeeping genes is <128 raw counts (or 7.0 in the log2-transformed counts).

The final genes in the model are listed in supplemental Table 1 with basic annotation from genecards.org. The 45-gene, 5-factor algorithm, including gene coefficients and threshold, was locked down before assessing in the independent validation cohort.

Independent validation

Blinded S0016 clinical trial samples (n = 272) were analyzed with the locked FL24Cx algorithm, and FL24Cx risk category calls were transferred to the SWOG Lymphoma Committee Biostatics group for correlation with patient outcomes and known clinical risk factors. The SWOG S0016 randomized phase 3 trial in FL compared R-CHOP to RIT-CHOP (R-CHOP followed by 131I-tositumomab consolidative radioimmunotherapy), finding similar outcomes.29,30

FL24Cx vs Huet validation comparison

Due to being performed on the same platform and some shared target genes, we compared the predictive ability of the FL24Cx model to that of the previously reported prognostic predictor from Huet et al19 by taking the log2 normalized nCounter gene expression counts for the genes in the Huet model, multiplied them by the weights specified in their article and calculated the signature score. Because the genes were evaluated as part of a different nCounter CodeSet and a different set of housekeeping genes, we could not directly translate the cut point to divide the samples into low-risk or high-risk prognostic groups. Instead, we evaluated the Huet model’s ability to predict EFS24 on the validation set with an ROC curve and compared it to a similar ROC curve based on the FL24Cx score (supplemental Figure 2). Recognizing that the scores were based on many of the same genes and therefore correlated, we evaluated the significance of the difference using bootstrapping. Data sets of equal size to the respective original were generated by resampling the original data with replacement. Then Huet and FL24Cx ROC curves were both regenerated from this set, and the difference between the areas under the curve (AUC) was calculated. This was repeated 10 000 times. Two-sided P values for the AUC difference were calculated by dividing the observed AUC difference on the complete data by the standard deviation of the bootstrapped AUC differences and comparing those values to the quantiles of a standard normal distribution.

Evaluation of IR1-IR2 synergy

Independently from the FL24Cx model, we reinvestigated the synergistic relationship between IR1 and IR2 that had been previously observed.25 We separately fitted 6 logistic regression models predicting EFS24. The first 2 consisted of modeling EFS24 as a function or IR1 alone in the training and validation sets, the next 2 consisted of fitting EFS24 as a function of IR2 alone in the training and validation sets, and the final 2 consisted of modeling EFS24 with a 2-variable model including both IR1 and IR2 in the training and validation sets.

Results

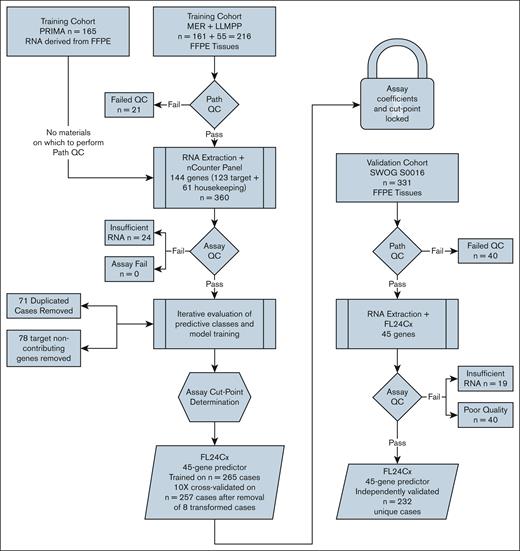

Figure 1 depicts the overall study schema. Briefly, the 144-gene nCounter panel was processed on 360 samples, 195 of which were from FFPE tissues qualified by on-site expert hematopathologist review, and 165 of which were from previously extracted RNA with accompanying pathology data; 24 patient samples were removed for inadequate RNA. After iterative modeling, during which 71 duplicate samples were found and excluded and 78 genes were eliminated, the locked 45-gene predictor was independently validated on 232 unique samples passing quality control metrics. Summary statistics for the training and validation cohorts are provided in Table 1.

Schematic diagram of study. The 144-gene nCounter panel was processed on 360 samples: 195 from FFPE tissues qualified by on-site expert hematopathologist review, and 165 from previously extracted RNA with accompanying pathology data, after which 24 samples were removed for inadequate RNA. After iterative modeling, during which 71 duplicate samples were identified and excluded and 78 genes were eliminated, the locked 45-gene predictor was independently validated on 232 unique samples that passed quality control metrics. LLMPP, Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project; MER, Molecular Epidemiological Resource; QC, quality control.

Schematic diagram of study. The 144-gene nCounter panel was processed on 360 samples: 195 from FFPE tissues qualified by on-site expert hematopathologist review, and 165 from previously extracted RNA with accompanying pathology data, after which 24 samples were removed for inadequate RNA. After iterative modeling, during which 71 duplicate samples were identified and excluded and 78 genes were eliminated, the locked 45-gene predictor was independently validated on 232 unique samples that passed quality control metrics. LLMPP, Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project; MER, Molecular Epidemiological Resource; QC, quality control.

Summary statistics of training and validation cohorts

| . | Training cohort LLMPP/MER n = 265, n (%) . | Validation cohort SWOG S0016 n = 232, n (%) . | 2-Sided P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 58 | 53 | |

| Sex, male | 153 (58) | 131 (56) | .800 |

| Elevated β2M | 51 (69) | 143 (62) | .300 |

| Unknown | 191 | 0 | |

| B symptoms | 50 (20) | 63 (27) | .067 |

| Unknown | 16 | 1 | |

| Bulk, >10 cm | 24 (10) | 51 (22) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 19 | 0 | |

| BM involvement | 95 (47) | 127 (55) | .089 |

| Unknown or indeterminate | 61 | 1 | |

| Histologic grade 3A | 77 (29) | 16 (7) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| Stage | <.001 | ||

| I-II | 56 (21) | 2 (1) | |

| III-IV | 207 (79) | 230 (99) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | |

| FLIPI risk | .002 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 74 (29) | 63 (27) | |

| Intermediate (2) | 79 (31) | 107 (46) | |

| High (3-5) | 99 (39) | 62 (27) | |

| Unknown | 13 | 0 | |

| FL24Cx risk | .024 | ||

| Low risk | 168 (63) | 169 (73) | |

| High risk | 97 (37) | 63 (27) |

| . | Training cohort LLMPP/MER n = 265, n (%) . | Validation cohort SWOG S0016 n = 232, n (%) . | 2-Sided P value∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median, y | 58 | 53 | |

| Sex, male | 153 (58) | 131 (56) | .800 |

| Elevated β2M | 51 (69) | 143 (62) | .300 |

| Unknown | 191 | 0 | |

| B symptoms | 50 (20) | 63 (27) | .067 |

| Unknown | 16 | 1 | |

| Bulk, >10 cm | 24 (10) | 51 (22) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 19 | 0 | |

| BM involvement | 95 (47) | 127 (55) | .089 |

| Unknown or indeterminate | 61 | 1 | |

| Histologic grade 3A | 77 (29) | 16 (7) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| Stage | <.001 | ||

| I-II | 56 (21) | 2 (1) | |

| III-IV | 207 (79) | 230 (99) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | |

| FLIPI risk | .002 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 74 (29) | 63 (27) | |

| Intermediate (2) | 79 (31) | 107 (46) | |

| High (3-5) | 99 (39) | 62 (27) | |

| Unknown | 13 | 0 | |

| FL24Cx risk | .024 | ||

| Low risk | 168 (63) | 169 (73) | |

| High risk | 97 (37) | 63 (27) |

β2M, β2-microglobulin; LLMPP, Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project; MER, Molecular Epidemiological Resource.

Pearson χ2 test.

Internal crossvalidation of the training cohort

Figure 2A visualizes expression levels for all 45 genes in the 5-factor (gene group) FL24Cx signature in all training samples (n = 265), ordered according to increasing model score, and demonstrates the optimal score cut point at which failure to achieve EFS24 is enriched in the poor prognosis or “high-risk” group, and achieving EFS24 is enriched in the good prognosis or “low-risk” group. Because the survival data were used to determine the model architecture, we applied 10-fold internal crossvalidation to reduce bias. The internally cross-validated low-risk group represented 63% of the samples and experienced a 13% EFS24 failure rate, whereas the high-risk group represented 37% of the samples and experienced a 49% EFS24 failure rate (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier curve of EFS in the training cohort stratified by cross-validated FL24Cx calls is shown in Figure 2B. The relative risk of failing EFS24 among patients classified into the high-risk group compared to those in the low-risk group was 2.49.

Development of the FL24Cx gene expression signature. (A) Heat map of 45-gene signature in training cohort with gene group designations and mapped to EFS24. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of EFS in cross-validated training data (24 months marked with vertical line), stratified by FL24Cx, with low-risk calls represented by the solid blue line and high-risk calls represented by the dashed red line.

Development of the FL24Cx gene expression signature. (A) Heat map of 45-gene signature in training cohort with gene group designations and mapped to EFS24. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve of EFS in cross-validated training data (24 months marked with vertical line), stratified by FL24Cx, with low-risk calls represented by the solid blue line and high-risk calls represented by the dashed red line.

Relationship between FL24Cx risk group prediction and failure to achieve EFS24 on internally cross-validated and validation cohorts

| . | Low risk by FL24Cx, n (%) . | High risk by FL24Cx, n (%) . | 2-Sided χ2P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal 10-fold crossvalidation of training cohort (n = 2570)∗ | n = 1609 (63) | n = 961 (37) | |

| Achieved EFS24, n = 1890 (74%) | 1396 (87) | 494 (51) | |

| Failed to achieve EFS24, n = 680 (26%) | 213 (13) | 467 (49) | N/A† |

| External independent validation cohort (n = 232) | n = 169 (73) | n = 63 (27) | |

| Achieved EFS24, n = 179 (77%) | 140 (83) | 39 (62) | |

| Failed to achieve EFS24, n = 53 (23%) | 29 (17) | 24 (38) | .0007 |

| . | Low risk by FL24Cx, n (%) . | High risk by FL24Cx, n (%) . | 2-Sided χ2P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal 10-fold crossvalidation of training cohort (n = 2570)∗ | n = 1609 (63) | n = 961 (37) | |

| Achieved EFS24, n = 1890 (74%) | 1396 (87) | 494 (51) | |

| Failed to achieve EFS24, n = 680 (26%) | 213 (13) | 467 (49) | N/A† |

| External independent validation cohort (n = 232) | n = 169 (73) | n = 63 (27) | |

| Achieved EFS24, n = 179 (77%) | 140 (83) | 39 (62) | |

| Failed to achieve EFS24, n = 53 (23%) | 29 (17) | 24 (38) | .0007 |

N/A, Not Applicable.

Eight of 265 samples with transformed status were excluded (257 samples × 10 model iterations = 2570).

No P value is reported in the internal validation of the training cohort.

Independent validation

The FL24Cx model, with locked weights and threshold, was applied unchanged, and in a fully blinded fashion to the previously unseen SWOG S0016 cohort. This group of patients represented those who received immunochemotherapy and had sufficient tissue for analysis. Of the attempted samples (n = 272), 40 were called “poor quality,” leaving 232 evaluable patients, corresponding to a sample success rate of 85%, including >20-year-old blocks and paraffin-dipped slides which required a more strenuous deparaffinization process before extraction. Patient characteristics by FL24Cx call are provided in supplemental Table 2. Patient characteristics between the subset of the S0016 cohort assayed were comparable to those of the combined S0016 R-CHOP and RIT-CHOP arms,29 with the exception of serum β2-microglobulin (supplemental Table 3). There was no interaction between the treatment arm and FL24Cx call (P = .15; data not shown).

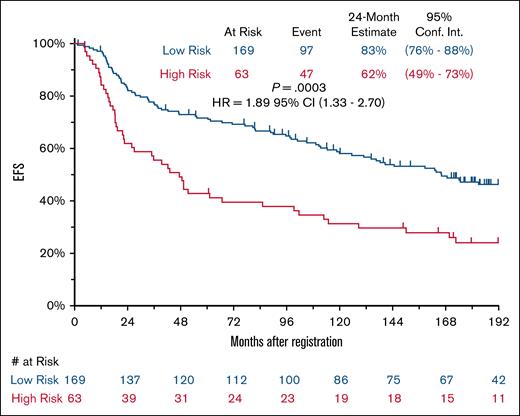

The successfully assayed samples derived from 232 patients, including 169 in the low-risk group and 63 in the high-risk group. The low-risk group experienced 29 (17.2%) EFS24 failures, whereas the high-risk group experienced 24 (38.1%) EFS24 failures (2-sided χ2P = .0007; Table 2). The relative risk of experiencing an early event among patients classified into the high-risk group compared to those in the low-risk group was 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.41-3.51); EFS for the cohort stratified by FL24Cx is shown in Figure 3 (hazard ratio for high-risk group, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.33-2.70; 2-sided log-rank P = .0003). OS at 15 years stratified by FL24Cx included 66% survival in the high-risk group and 76% in the low-risk group (hazard ratio, 1.17;95% CI, 0.70-1.94; log-rank P = .55; supplemental Figure 3A). FL-specific mortality, assessed by cumulative incidence function at 15 years stratified by FL24Cx, was 22% in the high-risk group (95% CI, 12-34), and 12% in the low-risk group (95% CI, 8-18; Gray P = .0806). OS at 15 years after 2-year landmark stratified by EFS24 showed 50% survival in the failed-to-achieve-EFS24 group and 77% survival in the achieved-EFS24 group (hazard ratio, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.44-4.49). FL-specific cumulative incidence function at 15 years stratified by EFS24 was 30% in the failed-to-achieve-EFS24 group (95% CI, 15-47), and 8% in the achieved-EFS24 group (95% CI, 4-13; Gray P = .0001.

Kaplan-Meier curve of EFS in validation cohort stratified by FL24Cx. Low-risk calls are represented by the blue line, and high-risk calls are represented by the red line. HR, hazard ratio.

Kaplan-Meier curve of EFS in validation cohort stratified by FL24Cx. Low-risk calls are represented by the blue line, and high-risk calls are represented by the red line. HR, hazard ratio.

FL24Cx vs Huet model

With the caveat that, due to difference in overall CodeSet, we could not fully recreate the model presented by Huet et al,19 an ROC analysis comparing the predictive power of the FL24Cx to the Huet model in the validation cohort showed a trend toward better performance of the FL24Cx model, although not the point of statistical significance (2-sided bootstrap P = .17).

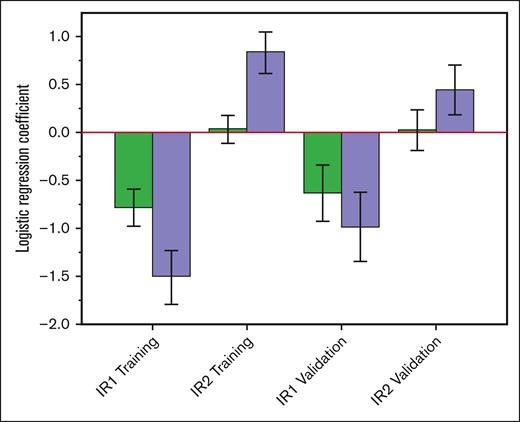

IR1-IR2 synergy

We confirmed the previously reported synergistic association of IR1 and IR2 in both the training and the validation cohort. In both cohorts, the IR1 and IR2 signature scores were well correlated (training, r = 0.56; validation, r = 0.60). Further, all model coefficients in both the training and validation sets showed a marked increase in magnitude when they were part of a combined model than when they were evaluated as single variables (Figure 4).

Bar graph of IR1/IR2 signature synergy. Green bars (left) show the coefficients for single-variable logistic regression models of EFS24 including either IR1 or IR2 alone. Purple bars (right) show their coefficients when included in a combined 2-variable model. Separate results are shown for both the training and validation cohorts. The increased magnitude of the coefficients in the combined model shows that they act synergistically. Error bars indicate the estimated standard error of the coefficients from the logistic models.

Bar graph of IR1/IR2 signature synergy. Green bars (left) show the coefficients for single-variable logistic regression models of EFS24 including either IR1 or IR2 alone. Purple bars (right) show their coefficients when included in a combined 2-variable model. Separate results are shown for both the training and validation cohorts. The increased magnitude of the coefficients in the combined model shows that they act synergistically. Error bars indicate the estimated standard error of the coefficients from the logistic models.

Prediction of transformation

Supplemental Figure 5 depicts the average model score grouped by outcome (higher model score is associated with poor prognosis/high risk). We observed that the average model score for the patients who transformed within 24 months was not significantly different from patients with no events. However, there was a significant difference in model scores between those experiencing early progression and transformation events, despite the small sample sizes (supplemental Figure 5).

Discussion

Due to the lengthy natural history of FL, clinical trial read out can take a long time when enrolling minimally selected populations. An up-front assay, rigorously validated in a clinical laboratory, to identify patients at high risk of early failure is the missing tool to rapidly conduct informative trials. By steering enrollment toward patients with a high risk of early failure, trials can be interpreted in a timely fashion to increase the pace of innovation.

Efforts to gauge patient OS risk at diagnosis or before treatment initiation based on tumor, rather than patient, characteristics are numerous. Pathological classification into grades 1, 2, 3A, and 3B have been traditionally used and provide important information. Although both grades 1 and 2 are considered low grade, grade 3B is considered more closely related to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with grade 3A still under study.31,32 The prognostic significance of many immunohistochemical markers, such as for Ki67, MUM1, or tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, have also been reported,31-42 as well as risk models combining biological and clinical factors such as assessing lack of intrafollicular CD4 expression as a modular addition to the FLIPI, termed “BioFLIPI.”43 GEP has been successfully used to interrogate FL biology associated with OS19,25 and first uncovered the importance of the tumor microenvironment in defining relevant biology and outcome.25

Whole exome sequencing has identified key genes and genomic breakpoints impacting FL biology,44-46 and genetic aberrations have been incorporated into prognostic models based on patient and tumor characteristics such as the m7-FLIPI,23 trained to failure-free survival, and the progression of disease at 24 months (POD24)–PI,47 trained to POD24. The m7-FLIPI and POD24-PI integrate the impact of nonsilent mutations in 7 or 3, respectively, key genes with the FLIPI score, with m7-FLIPI also using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status. Following initial publication, it appears that the utility of these models may vary for patients treated with different immunochemotherapy regimens.47-49 In addition, these clinical and biological models continue to reinforce that patients experiencing early events have less favorable outcomes.50-52 A comparison of the performance characteristics of FL24Cx vs m7-FLIPI and POD24-PI is shown in supplemental Table 4. Briefly, the FL24Cx performs similarly to both; however, the referenced sequencing method used for m7-FLIPI and POD24-PI is laborious, time consuming, requires 1 μg of DNA, has a higher technical failure rate (20.5% vs 14.7% of FL24Cx, and 2.5% of Lymph3Cx in newly diagnosed patients in real time53), and is dependent upon downstream analysis methods for somatic mutation detection, especially in the absence of matched normal specimens.

The newly developed FL24Cx algorithm performed well to predict EFS24 failure in the initial modeling, crossvalidation, and independent validation cohorts. However, it did not ultimately perform well to predict OS in the S0016 patient cohort with over 20 years of clinical follow-up. Because early events and OS are correlated, it was initially expected that the algorithm may also predict OS; however, the algorithm was specifically trained to EFS24 and thus is likely more indicative of true disease-specific events. An assessment of disease-specific cumulative incidence in the S0016 validation cohort revealed only 33 of 72 deaths (45%) were specific to FL, and when stratified by FL24Cx, the high-risk group had nearly twice the incidence rate of the low-risk group.

As individual signatures, IR1 and IR2 were strongly correlated, with IR1 showing a modest association with good survival and IR2 showed negligible association. However, when the 2 variables were combined into a multivariate model it was found that IR1 had a strong positive association with survival and IR2 had a strong negative association with survival. Effectively, the difference between IR1 and IR2 likely indicates different proportions of cell types within an overall difference in IR that is important to survival rather than the absolute number of infiltrating cells.25

A limitation of this work is the lack of distinction between progression and transformation events; however, progression events without transformation are much more frequent, associated with poor outcomes, and are thus important to identify.54 In the training set, we observed that although the model performed well for predicting disease progression and death, it did not independently predict transformation events (supplemental Figure 5). Excluding the transformation events in the training cohort did not decrease the power of the FL24Cx to predict EFS24 because, in our training cohort, progression accounted for nearly all of the early events, which is consistent with similar recently reported cohorts.55 FL transformation is known to occur from a wide variety of genetic aberrations and heterogeneous mechanisms via divergent clonal evolution.46,56,57 Nevertheless, in follow-up, we intend to explore FL24Cx utility in patients being treated with other chemotherapy backbones, such as bendamustine, which reduces FL progressions, whereas the number of transformations remains static, resulting in transformations accounting for a greater proportion of events.14,58,59 Furthermore, to assess FL24Cx utility in other treatment regimens, we will analyze samples from additional chemotherapy and nonchemotherapy regimens (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03269669, NCT01216683, NCT03789240, and NCT03223610) conducted by National Cancer Institute cooperative groups, intramural programs, and if possible, other studies of clinical interest. No serial biopsy samples before therapy were analyzed, so the stability of the signature over time is not known.

Although another algorithm developed on the nCounter platform by Huet et al19 performed well in our validation cohort, adjustments could be made to optimize it for the EFS24 end point. A specific clinical score, known as the FLIPI24, has also been developed to assess EFS24, and will be a source of future research to see how it performs compared against, and in addition to, the FL24Cx in a modular approach.51 Mutational data, to date, have been correlated with OS, not EFS24, which will be an on-going direction of investigation for future publications.

Ultimately, the powerful combination of tumor biology assessed by gene expression, sequencing, and spatial transcriptomics with clinical data (FLIPI or FLIPI24) will likely help to plan rational targets of frontline or rescue therapeutic intervention and understand long-term survival for high-risk patients, which current clinical models alone do not.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge members of the Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project research consortium who contributed and analyzed frozen materials for the initial Dave et al article, and some of whom also provided matched formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sister blocks for the migration to the nCounter platform, as well as their critical review of the assay development process. Part of the visual abstract was created using BioRender.com. Ramsower, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/3u27sb2.

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Lymphoma (P50-CA97274 [J.R.C.]); Hope Foundation 2023 Impact Award (L.M.R.); and NCI awards (UH2CA292129 [L.M.R.]; and U10CA180888 and U10CA180819 [J.W.F.]).

The authors acknowledge their late colleague Oliver Press, the original principal investigator of the S0016 trial.

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.R. designed research, performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; G.W. designed research, contributed vital analytical tools, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; H.L. and M.L.L. analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; J.R.C. and M.J.M. collected and contributed data, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; R.M. collected data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; A.C.R. collected data and wrote the manuscript; A.J.N., B.K.L., T.E.W., T.M.H., J.W.F., and D.W.S. contributed samples and data and wrote the manuscript; R.K., M.S., S.M.S., C.S., and L.M.S. contributed data and wrote the manuscript; and L.M.R. designed research, performed research, contributed samples and data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.C. reports research funding from Genentech and Genmab; and serves as a member of the safety and monitoring committee for Protagonist (all unrelated to this study). M.J.M. reports research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Roche/Genentech, and Genmab; and consultancy for BMS (all unrelated to this study). R.K. reports research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, and Roche; and has equity ownership in Telix Pharmaceuticals and ITM Isotope Technologies Munich SE (all unrelated to this study). D.W.S. reports consultancy for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genmab, Kite/Gilead, Roche, and Veracyte; research funding from Roche/Genentech; and is an inventor on patents describing the use of gene expression to subtype aggressive B-cell lymphomas, including one licensed to nanoString Technologies (all unrelated to this study). S.M.S. reports consultancy for Genmab, Regeneron, and Foresight; and S.M.S.'s spouse is employed by Caris Life Sciences (all unrelated to this study). B.K.L. reports research funding from Genentech, AbbVie, and Astra Zeneca (unrelated to this study). L.M.R. reports honoraria from Roche Tissue Diagnostics; and is an inventor on patents describing the use of gene expression to subtype aggressive B-cell lymphomas, including one licensed to nanoString Technologies (all unrelated to this study). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lisa M. Rimsza, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine–Tucson, The University of Arizona, 1501 N Campbell Ave, Tucson, AZ 85724; email: lrimsza@arizona.edu.

References

Author notes

C.A.R. and G.W. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Lisa M. Rimsza (lrimsza@arizona.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.