TO THE EDITOR:

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric malignancy, accounting for 25% of all childhood cancers and 80% of leukemias. It is a highly heterogeneous hematological malignancy, arising from transformed B-cell (B-ALL) or T-cell (T-ALL, ≈15%) precursors.1,2 In the previous decades, survival rates in T-ALL have significantly improved with event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival exceeding 85% in contemporary clinical trials.3,4 However, <25% of the relapsed patients survive, underscoring the need for new relapse predictors.3 Recent high-throughput analysis provided insights into the molecular landscape, enabling the identification of potential therapeutic targets and risk-stratification markers.5 For example, a recent study developed and validated a 14-gene mutation-based risk prediction model for T-ALL using targeted exome sequencing, highlighting the value of genetic profiling to define molecular risk groups in adult and pediatric cohorts.6 RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) enables the detection of fusion genes, expression profiles, and point mutations, which, taken all together, can be very relevant at diagnosis for patient stratification.7 In this study, we characterize a small cohort of patients with T-ALL with RNA-seq and focus on recurrent alterations to study their putative prognostic impact at diagnosis.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional ethics committees of the CEIm-E (Comité de ética para la investigación de medicamentos de Euskadi; PI+CES-BIOEF 2023-12).

Nine pediatric patients diagnosed with T-ALL between 2013 and 2018 in Spanish hospitals and treated under the SEHOP-PETHEMA 2013 protocol were analyzed in this study (SEHOP-PETHEMA cohort). Clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in supplemental Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 10 years (range 4-14 years), and male-to-female ratio was 2:1. One-third of the patients experienced at least 1 clinical event and died during follow-up. Blasts were measured in the cerebrospinal fluid for the assessment of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, stratifying patients into CNS1 (no blasts), CNS2 (<5 blasts/μL), and CNS3 (≥5 blasts/μL). Overall, 3 patients presented CNS involvement at diagnosis (1 CNS2 and 2 CNS3) and 2 were positive for end-of-induction minimal residual disease (MRD ≥ 1%). To study the genetic landscape of these patients, RNA-seq was performed as follows: total RNA (rRNA-depleted) obtained from tumor cells at diagnosis was sequenced using the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Reads were aligned to the hg38 reference using STAR version 2.7.9a,8 fusions detected with Arriba,9 and variants called and annotated using VarScan10 and Annovar,11 respectively. We selected exonic variants with ≥15 alternative allele reads and excluded synonymous or nonframeshift variants, those with a variant allele frequency smaller than 10% to remove subclonal alterations, and variants annotated in dbSNP with population frequencies >0.01. Alterations reported in >10% of samples but not previously annotated in Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer as mutated in T-ALL were discarded as potential artifacts.

Arriba reported 11 high-confidence fusion genes in 6 samples, from which only STIL::TAL1, a subtype-specific microdeletion in T-ALL, was observed in >1 sample (supplemental Table 2). This was identified in 2 patients without any clinical event during follow-up, supporting its association with good prognosis.12,13 Regarding point mutations and indels, 607 alterations (14-174 alterations per sample) were reported by VarScan (supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, 36 genes were altered in >1 sample, with USP7 being the most frequently mutated with 5 alterations in 3 patients. Remarkably, 2 of 3 patients who had an event during follow-up reported at least 1 alteration in USP7 (S353Kfs∗10 in TALL03 and E1034D, F1035L, and E1036Lfs∗7 in TALL09), whereas only 1 of the 6 patients without any clinical event did (R301Pfs∗14 in TALL04), none of them previously reported in T-ALL. The USP7 alterations found in our exploratory SEHOP-PETHEMA cohort were validated using Sanger sequencing on patients’ DNA at diagnosis.

USP7 encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme, a class of proteases responsible for cleaving protein-ubiquitin bonds. By removing ubiquitin modifications, these enzymes counteract the function of ubiquitin ligases such as MDM2, which targets TP53 protein, thereby regulating protein stability.14 Key targets of USP7 include PTEN, DNMT1, or the already mentioned MDM2 and TP53, being a crucial regulator in several diseases and cancer phenotypes.14-16USP7 is overexpressed in most cancers, which has led to significant research in recent years to identify USP7 inhibitors as promising novel drugs for the treatment of several malignances, including ALL.17

Considering the exploratory results obtained in the SEHOP-PETHEMA cohort, we extended the analysis to public data from patients treated according to Children’s Oncology Group AALL0434 clinical trial protocols, including 1276 patients analyzed in Pölönen et al18 to evaluate the consistency of these findings in a larger cohort (referred to as COG cohort here onwards). Access to public patient data was obtained through dbGaP (phs002276.v2.p1 and phs000218.v1.p119), BAM files were retrieved from the GDC20 and Kids First21 data portals, and variants were called and selected using the same pipeline as for our exploratory cohort. Additional cohorts were assessed for inclusion but were excluded due to a limited number of relevant cases or lack of disease representativeness.

Moreover, 146 USP7 variants were identified in 98 samples (7.68%), from which 70 were nonsynonymous single nucleotide variants (SNVs) that were present in 49 patients (3.84%; Figure 1A; supplemental Table 4). USP7 alterations and SNVs were enriched in TAL1 molecular group patients (91.84% and 85.71%, respectively), and no association between early T-cell precursor (ETP) immunophenotype and USP7 SNVs was observed (supplemental Table 5). The COG cohort demonstrated an 82.9% EFS and 84.5% disease-free survival (DFS), matching recent literature frequencies.3,4 When patients were classified based on USP7 alterations, those with USP7 SNVs had worse EFS and DFS (EFS: 78.9% vs 83.1%, P = .25; DFS: 75.5% vs 84.9%, P = .044). However, when restricting the analysis to pediatric patients (<15 years; n = 1032), thereby excluding adolescents and young adults based on previous studies,22 the differences became more pronounced. In this age group, patients reporting USP7 SNVs had poorer survival (EFS: 73.5% vs 82.9%, P = .045; DFS: 71% vs 84.9%, P = .0068; Figure 1B-C), suggesting a stronger clinical impact of USP7 SNVs in pediatric patients compared with adolescent and young adults. Interestingly, USP7 expression levels were comparable across patient groups, indicating that these differences in survival are unlikely to be explained by expression differences (supplemental Table 6).

USP7 alterations and survival outcomes in pediatric patients with T-ALL. (A) Lollipop plot23 revealing 146 USP7 alterations identified in the COG cohort. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for EFS comparing patient groups based on USP7 SNVs. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for DFS.

USP7 alterations and survival outcomes in pediatric patients with T-ALL. (A) Lollipop plot23 revealing 146 USP7 alterations identified in the COG cohort. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for EFS comparing patient groups based on USP7 SNVs. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for DFS.

In T-ALL, USP7 has been proposed to play an oncogenic role by deubiquitinating and stabilizing NOTCH1, a key driver of malignant transformation in this leukemia subtype.24,25 In addition, mutations in NOTCH1 and/or FBXW7, which result in constitutively active NOTCH1 signaling in ∼60% of patients, have been associated with good prognosis in some studies, highlighting the relevance of this gene in T-ALL.5

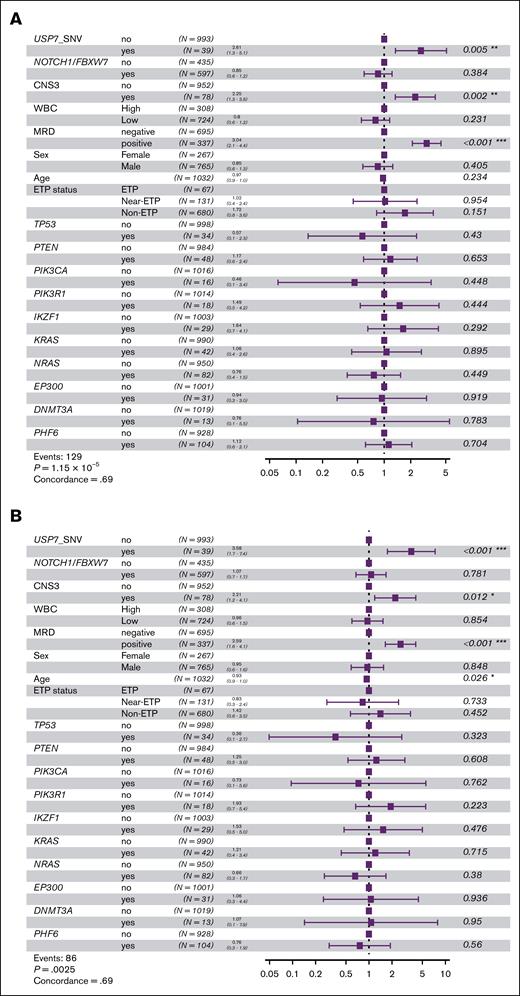

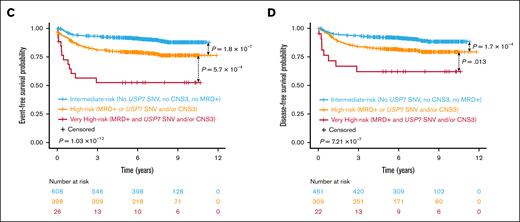

To further investigate, we analyzed those 2 genes and those included in the prognostic model proposed by Simonin et al6 using the same methodology (supplemental Table 4). We, then, evaluated the status of these genes alongside clinical variables previously associated with prognosis, such as end-of-induction MRD, white blood cell count (as a dichotomous variable: high ≥200 × 109/L and low), or CNS status, and USP7 SNVs in multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses in the subset of pediatric patients in the COG cohort. USP7 SNVs, CNS3 status, and positive MRD consistently turned up as independent markers of poor prognosis in EFS and DFS analyses (Figure 2A-B).

Survival outcomes in pediatric patients with T-ALL based on risk by key gene alterations and clinical variables. (A) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for EFS incorporating USP7 SNVs, alterations in the model genes of Simonin et al, and clinical variables. (B) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for DFS. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for EFS comparing risk groups by statistically significant variables in Cox analyses: CNS3 status, MRD, and USP7 SNVs. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for DFS.

Survival outcomes in pediatric patients with T-ALL based on risk by key gene alterations and clinical variables. (A) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for EFS incorporating USP7 SNVs, alterations in the model genes of Simonin et al, and clinical variables. (B) Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for DFS. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for EFS comparing risk groups by statistically significant variables in Cox analyses: CNS3 status, MRD, and USP7 SNVs. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve for DFS.

On the basis of these results, patients were stratified into risk groups as follows: those with positive MRD along with USP7 SNVs and/or CNS3 status were classified as “very high-risk”; patients with either positive MRD or USP7 SNVs and/or CNS3 status were considered as “high-risk” patients; and those without any of these poor prognosis markers were assigned to the “intermediate-risk” group. This stratification resulted in significantly different EFS and DFS outcomes across risk groups (EFS: 52.3% vs 76.3% vs 87.8%, P = 1.03 × 10−12; DFS: 62% vs 79.4% vs 88.5%, P = 7.21 × 10−7; Figure 2C-D).

Jin et al26 found that USP7 and USP11 affect LCK signaling in ALL, a pathway dysregulated in 30% to 45% of T-ALL cases and linked to dasatinib sensitivity. In our data, the gene ontology (GO) term including LCK (GO:0007169) was highly enriched in overrepresentation analyses with significantly differentially expressed genes between children with and without USP7 SNVs (q = 2.98 × 10−12), suggesting USP7 SNVs may affect this pathway, although LCK gene expression differences are subtle (supplemental Table 6). Although further validation is warranted, these results raise the possibility that dasatinib could be explored as an alternative therapeutic strategy in high-risk pediatric patients with T-ALL harboring USP7 SNVs.

Overall, our data suggest that USP7 SNVs may represent a novel marker of poor prognosis, which, in combination with MRD and CNS status, could help identify a subgroup of very high-risk pediatric patients with T-ALL.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Basque Biobank, integrated in the Spanish Biobank Network of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), for the sample and data procurement. The authors also thank Cheng Cheng from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for his help and assistance with the analysis of unpublished data. Technical and human support provided by IZO-SGI SGIker (UPV/EHU, MICINN, GV/EJ, ESF) is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by Fundación Mutua Madrileña (AP171202019), Fundación vasca de innovación e investigación sanitarias (BIO20/CI/015/BCB), and the Basque Government (IT1559-22 and 2021111028). U.I. was supported by the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) through a predoctoral fellowship. A.G.-C. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Fundación Vasca de Innovación e Investigación Sanitarias (BIO20/CI/016/BIOEF).The results analyzed and published here are based in whole or in part upon data generated by the Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program projects and by the National Cancer Institute's Childhood Cancer Data Initiative supplemental funding to share data generated in this project with the research community under grant no. 3P30CA008748-54S3 phs.002276.v2.p1. The results published here are in part based upon data generated by the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/target) initiative, phs000464.

Contribution: U.I., I.M.-G., and E.L.-L. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, and writing of the original draft; U.I. and E.A. contributed to software, formal analysis, and visualization; A.G.-C. contributed to resources and investigation; R.L.-A., J.A.-M., M.R.-O., D.S., and I.A. contributed to resources; I.A., I.M.-G., and E.L.-L. contributed to funding acquisition; all authors contributed to the review and final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Idoia Martin-Guerrero, Department of Genetics, Physical Anthropology and Animal Physiology, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of The Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Barrio Sarriena s/n, 48940 Leioa, Basque Country, Spain; email: idoia.marting@ehu.eus.

References

Author notes

RNA-sequencing data are available at the Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA1186080. Code used for survival analyses is available at: https://github.com/uillar/USP7_T-ALL.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.