As our approaches to the management of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have become more effective, they have introduced new administrative complexities. These include challenges pertaining to medication administration and financial implications of treatment choices. Because approximately half of these patients are typically treated outside of larger referral centers, these difficulties are being passed on to clinicians in settings that rarely encounter this complex disease. Instead of an evidence-focused review on contemporary management of ALL in adults, this article seeks to highlight how some of these important medical advances may be difficult to operationalize outside of high-volume centers. It will also attempt to identify areas in which clinicians and investigators might consider modifying their respective approaches to mitigate how the realities of modern medical care may affect our ability to optimally manage these patients now and in the future.

Introduction

Outcomes for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have improved significantly over the past several decades.1 There are multiple advances to which these favorable developments may be credited, some of which have leveraged novel, first-in-class technologies. Our ability to risk-stratify patients has become more sophisticated, which speaks to an expanding knowledge of the underlying biology of the disease. The use of sensitive techniques for disease detection have made ALL one of the few diseases in which minimal or measurable residual disease is an established tool for routine medical practice.2 The assays on which these methods rely are now helping clinicians recognize more accurately basic tenets of cancer treatment, such as when our interventions are likely to work and how well they have worked. This information can then be used to guide far more complicated decisions, such as whether to refer patients for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) while in first remission.3

The treatments themselves have also evolved remarkably. At the dawn of the 21st century, a “one-size-fits-all” approach of multiagent chemotherapy regimens was still being used across the spectrum of ages and disease subtypes.4-7 Unfortunately, when these complex treatments failed, the prognosis was very poor. Nearly all adult patients with relapsed or refractory ALL died within 2 years, either from their disease or complications from unsuccessful attempts to treat it with more chemotherapy.8 Fortunately, new treatments were first developed in the relapsed/refractory setting.9-13 These included the first agents in entirely new classes of immunotherapy drugs. There was also the advent of ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which could be safely added to chemotherapy in cases in which the disease harbors the BCR::ABL1 translocation or is Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+).14-16 We have also seen increased use of so-called pediatric-inspired therapy in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with Ph– ALL based on compelling retrospective and prospective data.17,18 Although randomized trials were infrequent, these advances in the 2000s and 2010s led to significant changes in practice patterns and the outlook for patients.

In just the last few years, we have seen impressive results emerge from prospective trials that have brought some of these immunotherapy agents into the frontline setting.19-24 This has also helped usher in a more refined way of thinking about ALL in adults, with Ph– and Ph+ disease treated in distinctly different ways. Some of these newer strategies have also helped facilitate less reliance on cytotoxic chemotherapy, a particular challenge for older adults (eg, older than 60 years) who develop ALL. Arguably the most impressive example of this is in Ph+ B-cell ALL: this can now be treated effectively with approaches that consist primarily of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and blinatumomab; this can mean no systemic chemotherapy, infrequent hospitalizations, and a diminishing role of HCT.25-27 Indeed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have evolved to reflect these latest treatment approaches.28 The most recent iteration includes separate pathways for newly diagnosed B vs T lineage and Ph+ vs Ph– disease, along with a variety of options for AYAs vs adults (including specific recommendations for older adults and those with significant medical comorbidities).

Coinciding with the advent of many of these latest developments, my postfellowship medical career began in 2014. Since that time, my clinical practice and research have focused almost entirely on adults with ALL. I have therefore witnessed firsthand the remarkable changes that have occurred in the management of this rare and difficult disease. I have also been fortunate enough to play a modest role in the study and implementation of some of these latest advances. It is with the pride that has come from these opportunities that I offer the following perspective: we are undoubtedly making the treatment of this disease better for many who are impacted by it; however, these efforts are also making it increasingly difficult to deliver such excellent outcomes to those outside the most well-resourced and specialized settings. Many of our newest strategies introduce layers of administrative complexity to a disease whose treatment was already on the extreme end of this spectrum.

As we ponder future clinical trials, I believe our small field could benefit from reflecting on its strategies and priorities, to avoid leaving large swaths of the population behind (even within a country as well-resourced as the United States). Although I hope a broad audience finds this interesting, the readers I am primarily targeting are investigators in academia and industry who help advance the treatment of adults with ALL and strive to usher in further improvements. I seek not to disparage the steps we have taken but rather to encourage a path that helps our future progress affect as many patients as possible.

Practical considerations when treating adults with ALL

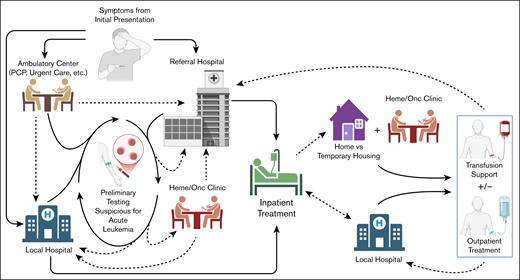

When considering the current landscape of adult ALL management, it is important to understand how and where this typically occurs, which is somewhat unique (Figure 1). To those of us who treat this disease regularly, these will be familiar concepts. However, for those with less direct experience (eg, our industry partners who contribute to study design), it is critically important to understand this context, because these patients and their medical providers face these challenges routinely.

Complex interplay between inpatient vs outpatient care and local vs referral medical systems that makes up the current management of adults with ALL. When these patients come to medical attention, they can do so via different entry points. An initial evaluation typically identifies some suspicious findings. From here, many are referred to larger centers with expertise in managing this diagnosis. However, this is not the case for all, particularly if getting to the referral center is prohibitively difficult for logistical or financial reasons; in these cases, patients will often remain at their local hospital, as long as this facility can provide the required level of care. Treatment for ALL typically starts within days of the initial diagnosis and virtually always on an inpatient basis. After a period of inpatient observation, patients who are medically stable may discharge with close outpatient follow-up, provided this center is able to deliver the necessary ongoing care. Otherwise, they may require a longer period of inpatient monitoring to ensure they have consistent access to critical supportive care such as transfusions and any ongoing treatment their regimen includes, etc. Then, depending on the specific approach being used and social factors, management may require repeated hospitalization, continued treatment as an outpatient, and/or referral back to a local facility. Dashed lines are meant to represent transitions in the location of care delivery (eg, inpatient to outpatient). Heme/Onc, hematology/oncology; PCP, primary care provider. Figure created using biorender.com. Cassaday R.D. (2025) https://biorender.com/05k7ae9.

Complex interplay between inpatient vs outpatient care and local vs referral medical systems that makes up the current management of adults with ALL. When these patients come to medical attention, they can do so via different entry points. An initial evaluation typically identifies some suspicious findings. From here, many are referred to larger centers with expertise in managing this diagnosis. However, this is not the case for all, particularly if getting to the referral center is prohibitively difficult for logistical or financial reasons; in these cases, patients will often remain at their local hospital, as long as this facility can provide the required level of care. Treatment for ALL typically starts within days of the initial diagnosis and virtually always on an inpatient basis. After a period of inpatient observation, patients who are medically stable may discharge with close outpatient follow-up, provided this center is able to deliver the necessary ongoing care. Otherwise, they may require a longer period of inpatient monitoring to ensure they have consistent access to critical supportive care such as transfusions and any ongoing treatment their regimen includes, etc. Then, depending on the specific approach being used and social factors, management may require repeated hospitalization, continued treatment as an outpatient, and/or referral back to a local facility. Dashed lines are meant to represent transitions in the location of care delivery (eg, inpatient to outpatient). Heme/Onc, hematology/oncology; PCP, primary care provider. Figure created using biorender.com. Cassaday R.D. (2025) https://biorender.com/05k7ae9.

Most patients come to medical attention due to symptoms or signs that are a direct consequence of their leukemia; in other words, it is exceedingly rare that this is an incidental finding or stumbled upon during routine screening or monitoring visits. Because of this and the fact that the disease generally progresses briskly, patients are often whisked urgently toward facilities that can manage high-grade hematologic malignancies. This can sometimes be done first as an outpatient, but unless the patient can be seen within a few days, they often end up in an emergency department for worsening complications from their leukemia (eg, pain and consequences of severe cytopenias, etc) and/or concerns from the referring physician about what might happen to them in an ambulatory setting. If the patient is in a more remote location, this may require medical input on options for safe transportation. Even when patients are seen in our clinic first for an outpatient consultation, they invariably require hospital admission to facilitate treatment delivery.

This very short time from initial suspicion to confirmed diagnosis to treatment initiation requires systems to be very nimble. This is important not only for patient safety but also for inpatient resource utilization. We generally will not start treatment until we have independently confirmed the diagnosis is ALL, which can be done most rapidly via multiparameter flow cytometry on peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirate. In some cases, this is sufficient to make treatment decisions. However, there are cases in which treatment may change significantly based on the Ph status (eg, pediatric-inspired therapy vs hyperCVAD [part A: hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone, alternating with part B: methotrexate and cytarabine] plus ponatinib for an AYA with Ph– vs Ph+ ALL, respectively). The days that it takes to obtain this information can be spent addressing other important matters: helping the patient and family come to grips with this highly consequential diagnosis, counsel them on different treatment options, place a central venous catheter, pursue fertility preservation if desired, and complete additional staging workup when appropriate, etc. Before treatment starts, and when the disease burden is high, it is also important to consider plans for future minimal or measurable residual disease testing. Some assays require a baseline sample for characterization, so failing to address this early could complicate evaluations of response later.29

This initial workup can be complicated further by the need to assess sites of extramedullary disease. When this is the dominant presentation (ie, <25% marrow blasts), it is called lymphoblastic lymphoma. The most important of these is the central nervous system (CNS), with the leptomeninges being the most common anatomic location.30 All patients must undergo lumbar puncture (LP) for diagnostic evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid and for administration of intrathecal chemotherapy.28 The optimal timing of the first LP can be difficult to ascertain: although most protocols require one at diagnosis, circulating blasts raise concerns about seeding the CNS after a traumatic LP. Furthermore, contaminating the laboratory cerebrospinal fluid specimen with peripheral blood can confound interpretation of both cytospin and multiparameter flow cytometry. Some centers (including our own) will delay the first LP until peripheral blasts clear after a few days of systemic therapy.31 This common practice does not align with eligibility criteria that mandate knowing CNS status before initiating therapy. Then there is the issue of evaluating non-CNS sites of extramedullary disease, often dictated by the presence of localizing symptoms. Positron emission tomography (PET) is often pursued, for which there are formalized response criteria.28 For reasons of financial reimbursement (explored further under “Barriers to care delivery for adults with ALL”), this can be challenging to perform on hospitalized patients. Because ALL and lymphoblastic lymphoma are generally treated the same, it can be difficult to justify efforts to obtain PET in these often-fraught first few days. Because it is arguably most important to see what persists by PET after treatment, it can still be pursued later as an outpatient when practically less challenging.

Once treatment begins, close monitoring for the unique complications of starting induction therapy is required. This includes tumor lysis syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation. These risks have usually passed within 3 to 4 days, after which the barriers to hospital discharge become more general medical in nature: whether symptoms are adequately controlled, whether there is an outpatient care plan in place, and whether the patient has secure housing and caregivers, etc. Patients will frequently require transfusion support, so they will need to remain in or near a facility that can provide this level of care on short notice. Depending on the specific treatment chosen, there may be additional chemotherapy to deliver in the subsequent days and weeks to complete the induction course. Importantly, this level of care may exceed what most cancer centers can provide for an outpatient, meaning the patient may remain in the hospital for the first 3 to 4 weeks of treatment. In particularly well-staffed centers such as ours, we can typically discharge patients ∼4 to 5 days into their induction course, with the remainder of care provided in our clinic (barring any complications).

From there, things generally pivot toward consolidation therapy, which (again) may require more hospital admissions in addition to frequent outpatient visits. For example, the C10403 pediatric-inspired regimen can generally be administered entirely in an ambulatory setting.18 On the contrary, the 2 components of hyperCVAD (ie, parts A and B) have schedules of chemotherapy administration that would be very difficult to give to an outpatient (eg, IV infusions every 12 hours),32 so this approach typically requires alternating between hospitalization and ambulatory care. All regimens will include ongoing LPs for intrathecal chemotherapy. For Ph– and for some approaches in Ph+ B-cell ALL, the inclusion of blinatumomab for consolidation typically requires hospitalization at least for the start of the first 2 4-week treatment cycles.23,33 These inpatient stays can be brief if the drug can be delivered via an outpatient infusion service through a central venous catheter. Because this agent is typically not added until several months into treatment, there is usually more time to make the necessary preparations.

The point of this description is to emphasize the relatively short amount of time and inpatient setting under which virtually all adults with ALL are treated. Therefore, the choices that are made in those hectic first days will reverberate across many encounters with the health care system, including the potential for multiple (and sometimes lengthy) hospitalizations. It is also worth reiterating that I work at a large academic referral center, so our system is equipped and staffed to address some of these unique challenges. Nonetheless, similar to any medical institution, our processes are not perfect. From informal discussions with colleagues in similar roles at other centers and through working with referring physicians who send patients to our facility, I suspect the preceding descriptions are largely reflective of how most hospitals and clinics that treat this disease operate. Future work could survey a range of treaters of adults with ALL to better understand some of these details, particularly when limitations have been identified. Prospective studies could then account for these during their design and implementation.

Barriers to care delivery for adults with ALL

Expert panels such as those convened by NCCN and European LeukemiaNet advocate that these patients are treated in high-volume centers when possible.28,34 When it comes to pursuing chimeric antigen receptor–modified T-cell therapy or HCT, such referrals are essential, because these options are only available at accredited sites. Despite these overarching beliefs about the optimal approach to managing adults with ALL, it is estimated that only approximately half of adults with ALL in the United States are treated at academic centers.35 This is true even among AYAs, in whom the trends toward the use of complicated and specialized pediatric-inspired therapy would seemingly provide an even greater motivation.36 Some centers have formalized AYA programs to cater specifically to the unique needs of this vulnerable population (eg, dedicated fertility counseling and social services, etc).37 For the half who are treated at such institutions, this can still come with its own set of psychosocial and logistical challenges if they do not live nearby: transportation, housing, adequate caregiver support, loss or interruption of their employment (and thus income), and displacement from established social networks, etc. On the contrary, this means that the remaining half of patients not treated in academic centers may be receiving their care at smaller-volume facilities with less experience in the nuances of this diagnosis. When hospitals and clinics encounter these uncommon patients, they may rely on a certain level of institutional comfort or experience to ensure the care they deliver is safe, effective, and expedient.

Consider a rural oncology practice that only sees 1 adult with ALL every few years: there may or may not be sufficient bandwidth among their staff (providers, pathologists, pharmacists, nurses, etc) to integrate all the “latest and greatest” advances, some of which are not applicable to most patients they serve. This is likely why the hyperCVAD regimen remains a very common choice in such practices. Although not used as the chemotherapy backbone in the most recent randomized trials,23,38,39 there are analogous single-arm studies with hyperCVAD from which the superiority of these interventions may be extrapolated.16,33,40 From a more practical perspective, it is a relatively straightforward regimen to administer (at least by ALL standards) and versatile across a range of patient and disease characteristics.32 It also does not routinely include any uncommon or high-cost medications, a feature that makes it easier to implement. This particular topic will be explored next.

The cost of medications is another important factor in the feasibility of caring for adults with ALL. There are numerous variables that contribute to this: an exhaustive review of them is outside the scope of this commentary, but others have taken on this complicated topic.41 However, there are some important practical considerations for clinicians to consider beyond basic details such as individual drug cost and patient insurance coverage. For example, pharmacies affiliated with outpatient infusion centers may be less comfortable procuring expensive drugs for rarely seen indications, particularly if the shelf life is short or the storage requirements are cumbersome.

Then there are the differences in reimbursement for inpatient vs outpatient delivery of medications. Outpatient drug administration is billed separately, allowing health care organizations to be paid specifically for this service. Added to this is the reality that price markups by hospital-based outpatient centers is common and significant, including for cancer medications.42,43 In contrast, most hospitals in the United States are paid under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System.44 Devised by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, it relies on Diagnosis Related Groups to assign predetermined amounts that are paid to hospitals, based in part on severity of illness.45 Essentially, hospitals receive a set amount per patient for the care delivered during an admission, regardless of the specific interventions delivered. Because hospitals must spend money to acquire high-cost items such as expensive oncology therapeutics, this structure can dramatically undercut the net intake the hospital ultimately receives. Thus, hospitals have less financial liability when these events occur on an outpatient basis.

These pressures may not be felt directly by clinicians on the frontlines, but their impacts are more apparent when trying to treat an adult with ALL. Smaller facilities may choose not to include certain medications on their formularies that are uniquely used for this rare indication (eg, pegaspargase and inotuzumab ozogamicin [InO]) due to some of the factors previously mentioned. Challenges can also arise with blinatumomab due to both its cost and its reliance on prolonged continuous infusion. I have heard anecdotes from colleagues that work in smaller systems in which this can influence their treatment decisions. Table 1 highlights some of the practical issues that can be encountered with drugs that are uniquely used for ALL; again, as noted in the “Practical Considerations” section, those tasked with helping design clinical trials in adults with ALL may have less personal experience with some of these challenges.

Selection of drugs used in the treatment of adults with ALL and the characteristics that make them challenging to administer

| Drug name (and class) . | NCCN recommended use . | FDA-approved indications . | Unique challenges with delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blin (BiTE) | Combined with TKI for Ph+ B-ALL R/R B-ALL Consolidation after chemotherapy for Ph– B-ALL | Consolidation after chemotherapy for Ph– B-ALL MRD+ B-ALL R/R B-ALL | High cost Administered via 28-d continuous IV infusion Idiosyncratic side-effect profile |

| Brexu-cel, obe-cel, and tisa-cel (CAR-T) | R/R B-ALL∗ | R/R B-ALL∗ | High cost Available only at certified sites Complexities of cell collection and manufacturing Idiosyncratic side-effect profile |

| InO (ADC) | Induction therapy of B-ALL aged ≥65 years Combined with mini-hyperCVD for newly diagnosed or R/R B-ALL R/R B-ALL (including with TKI for Ph+ ALL) | R/R B-ALL | High cost |

| Nelarabine (antimetabolite) | Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed T-ALL R/R T-ALL | T-ALL that has not responded to or relapsed after 2 prior chemotherapy regimens | High cost Very rare indication |

| Pegaspargase (asparaginase) | Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed and R/R Ph– ALL Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for R/R Ph+ ALL refractory to TKI | Combination with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed ALL | High cost Idiosyncratic side-effect profile Limited shelf life |

| Ponatinib (TKI) | Combined with blin, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid for newly diagnosed Ph+ B-ALL Single agent or combined with blin or InO for R/R Ph+ ALL | Combined with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL T315I mutated Ph+ ALL or if no other TKIs are indicated | Copay considerations for prescription coverage May only be available through specialty mail-order pharmacy |

| Recombinant Erwinia asparaginase (asparaginase) | Substitution for pegaspargase after hypersensitivity reaction as part of multiagent chemotherapy regimen | Part of multiagent chemotherapy regimen after hypersensitivity to Escherichia coli–derived asparaginase | High cost Idiosyncratic side-effect profile Very rare indication |

| Drug name (and class) . | NCCN recommended use . | FDA-approved indications . | Unique challenges with delivery . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blin (BiTE) | Combined with TKI for Ph+ B-ALL R/R B-ALL Consolidation after chemotherapy for Ph– B-ALL | Consolidation after chemotherapy for Ph– B-ALL MRD+ B-ALL R/R B-ALL | High cost Administered via 28-d continuous IV infusion Idiosyncratic side-effect profile |

| Brexu-cel, obe-cel, and tisa-cel (CAR-T) | R/R B-ALL∗ | R/R B-ALL∗ | High cost Available only at certified sites Complexities of cell collection and manufacturing Idiosyncratic side-effect profile |

| InO (ADC) | Induction therapy of B-ALL aged ≥65 years Combined with mini-hyperCVD for newly diagnosed or R/R B-ALL R/R B-ALL (including with TKI for Ph+ ALL) | R/R B-ALL | High cost |

| Nelarabine (antimetabolite) | Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed T-ALL R/R T-ALL | T-ALL that has not responded to or relapsed after 2 prior chemotherapy regimens | High cost Very rare indication |

| Pegaspargase (asparaginase) | Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed and R/R Ph– ALL Combined with multiagent chemotherapy for R/R Ph+ ALL refractory to TKI | Combination with multiagent chemotherapy for newly diagnosed ALL | High cost Idiosyncratic side-effect profile Limited shelf life |

| Ponatinib (TKI) | Combined with blin, chemotherapy, or corticosteroid for newly diagnosed Ph+ B-ALL Single agent or combined with blin or InO for R/R Ph+ ALL | Combined with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Ph+ ALL T315I mutated Ph+ ALL or if no other TKIs are indicated | Copay considerations for prescription coverage May only be available through specialty mail-order pharmacy |

| Recombinant Erwinia asparaginase (asparaginase) | Substitution for pegaspargase after hypersensitivity reaction as part of multiagent chemotherapy regimen | Part of multiagent chemotherapy regimen after hypersensitivity to Escherichia coli–derived asparaginase | High cost Idiosyncratic side-effect profile Very rare indication |

Drugs are listed in alphabetical order by generic name. All uses are as single agents unless designated as combinations.

ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; blin, blinatumomab; BiTE, bispecific T-cell engager; brexu-cel, brexucabtagene autoleucel; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor–modified T-cell therapy; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; InO, inotuzumab ozogamicin; obe-cel, obecabtagene autoleucel; MRD, measurable/minimal residual disease; R/R, relapsed or refractory; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

For tisa-cel only, the NCCN recommendation and FDA approval include these qualifications: age <26 years with either refractory disease or second or greater relapse.

The issue of reimbursement for inpatient vs outpatient administration of medications is particularly important in ALL. Although many centers (including ours) can deliver much of the care in an ambulatory setting, admission to the hospital is necessary under many different circumstances. As noted above, virtually everyone requires admission when they are first diagnosed. Thus, if the initial therapy chosen includes early and/or frequent administration of costly medications, these challenges will be encountered. This may be limited to modest administrative hurdles, such as requesting approval from hospital-appointed high-cost drug committees.46 It may also lead to weightier discussions with hospital administrators who must concern themselves with broader issues such as institutional cost containment.

Suggestions for potential improvement

The successes we have seen with the latest approaches for adults with ALL make it difficult to articulate a plausible case for change. As a physician, my primary responsibility is for the patient and family with whom I sit in that examination or hospital room. It is highly gratifying to offer therapies that are more effective and less toxic. However, if we can also make these treatments more feasible and attainable without sacrificing their attributes, we stand to ease burdens on our medical infrastructure. Most aspirational, we also may find approaches that help those afflicted with this disease in lower-resource areas. In this context, I propose several strategies that could be implemented and tested to advance these goals (Table 2); those that I think deserve particular attention are detailed further below.

Suggestions for how to address practical challenges and shortcomings in the current management of adults with ALL

| Proposed action . | Issues addressed . | Potential benefits . |

|---|---|---|

| Confirm feasibility of later phases of treatment plan when frontline therapy is initially selected | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers | Better adherence to intended (and presumably optimal) treatment plan Mitigate challenges related to patient housing and transportation Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems |

| Transition high-cost IV medications to outpatient administration when appropriate | Possible discrepancies between inpatient and outpatient reimbursement for medication administration | Improved financial compensation for medical system Simplify inpatient pharmacy workflows by reducing utilization of rarely used medications |

| Consider likely sites of care when designing prospective studies of novel agents and/or combinations | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Possible discrepancies between inpatient and outpatient reimbursement Overall costs of care | Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Improved financial compensation for medical system Reduce financial toxicity |

| Commit to performing randomized controlled trials to validate superiority of treatment approaches | Limited evidence to support optimal treatment sequencing Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Overall costs of care | Increase confidence in effectiveness of treatment plans Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Reduce financial toxicity (if more costly approaches do not improve outcomes) |

| Invest in clinical trials studying approaches that remain feasible in lower-resource settings | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Overall costs of care | Increase confidence in effectiveness of treatment plans Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Mitigate challenges related to patient housing and transportation Reduce financial toxicity (if more costly approaches do not improve outcomes) |

| Proposed action . | Issues addressed . | Potential benefits . |

|---|---|---|

| Confirm feasibility of later phases of treatment plan when frontline therapy is initially selected | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers | Better adherence to intended (and presumably optimal) treatment plan Mitigate challenges related to patient housing and transportation Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems |

| Transition high-cost IV medications to outpatient administration when appropriate | Possible discrepancies between inpatient and outpatient reimbursement for medication administration | Improved financial compensation for medical system Simplify inpatient pharmacy workflows by reducing utilization of rarely used medications |

| Consider likely sites of care when designing prospective studies of novel agents and/or combinations | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Possible discrepancies between inpatient and outpatient reimbursement Overall costs of care | Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Improved financial compensation for medical system Reduce financial toxicity |

| Commit to performing randomized controlled trials to validate superiority of treatment approaches | Limited evidence to support optimal treatment sequencing Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Overall costs of care | Increase confidence in effectiveness of treatment plans Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Reduce financial toxicity (if more costly approaches do not improve outcomes) |

| Invest in clinical trials studying approaches that remain feasible in lower-resource settings | Complexity of contemporary treatment approaches Frequent transitions of care between referral and local medical centers Overall costs of care | Increase confidence in effectiveness of treatment plans Preserve comfort level of community providers and medical systems Mitigate challenges related to patient housing and transportation Reduce financial toxicity (if more costly approaches do not improve outcomes) |

Whether on an individual patient basis or when making broader recommendations such as those from NCCN or European LeukemiaNet, the complex downstream environment in which patients with ALL are managed must be considered (Figure 1). If every patient were managed at high-volume centers for the duration of their treatment, these systems should be equipped to deliver all aspects of care, regardless of how the regimen changes. However, given the frequent transitions in care that occur, it is imperative that the approach chosen at the time of initial diagnosis can “travel” with the patient to wherever they might go. In the case of a patient being transferred a greater distance to a referral center at initial diagnosis, smaller medical facilities closer to their home may face serious challenges trying to implement something that is new and different for them. Otherwise, patients may get “stuck” and face additional psychosocial stresses from being displaced for a longer time. This is arguably most apparent with regimens that routinely include blinatumomab during consolidation.20,21,23 There is optimism that a new subcutaneous formulation of this drug will lessen some of the burdens imposed by the continuous IV formulation; definitive clinical trials with this product are still ongoing.47

One relatively simple intervention that could be used (and may already occur in some centers) is to make subtle adjustments to the schedule of drug administration when possible. If a treatment can just as safely and effectively be given a day or 2 earlier or later without it occurring during a scheduled hospitalization, this could sidestep issues with Diagnosis Related Groups-based reimbursement, yielding a significant net financial benefit for the medical system. One applicable example is the first dose of pegaspargase given with the remission induction course of C10403: the schedule in the original trial allowed this dose to be administered between days 4 and 6.18 If medically appropriate, patients could be observed for the first few days of induction for things such as tumor lysis syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation, with pegaspargase deferred until after discharge. Unfortunately, some regimens lack this flexibility by virtue of their design. Those that rely primarily (if not entirely) on InO during induction would necessitate some inpatient administration of this drug for virtually all patients.22,48

Researchers should keep these matters in mind when studies are developed to test new combinations or novel drugs. Clearly, pharmacologic characteristics that optimize safety, promote synergistic anticancer activity, and feasibility are the top priorities. In many oncology indications, treatment is primarily in the outpatient domain. Convenience is often emphasized to make the treatment more palatable for real-world implementation. This leads to most or all the drugs being given together or in rapid succession to cut down on clinic visits and associated travel. However, in a world where treatment is occurring in the hospital also, this approach potentially introduces these administrative challenges. Unfortunately, these patients generally need to come to clinic multiple times per week during treatment already for supportive care (see the “Practical Considerations” section; Figure 1), undercutting the convenience argument. Take for example the mini-hyperCVD plus InO combination pioneered at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Although the dosing approach has changed over time, the latest iteration gives InO on days 2 and 8.49 Fractionating into 2 doses appears to reduce toxicity, but otherwise there is no known biologic or pharmacologic rationale for this specific timing. In most systems, the day 2 dose would need to be given inpatient to coordinate with the concurrent administration of mini-hyperCVD. On the contrary, when our group studied the combination of InO with dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin), InO is given on days 8 and 15.50 This allowed for us to administer >90% of these doses as an outpatient.51 Although I cannot claim superiority of one approach over the other, practical matters such as this deserve consideration, particularly when traditional outcomes such as response rate and survival are similar.

The final point on which to elaborate here is the importance of randomized controlled trials. In a disease as rare as adult ALL, such efforts are monumental; those who have successfully completed them are to be commended.7,10,11,23,38 Perhaps their greatest value in our field now is to ensure we understand the impact of sequencing of treatments. Single-arm trials with both InO and blinatumomab upfront may have yielded improvements when compared to historical controls.48,49 However, what these approaches cannot address is a fundamental question: is it truly the inclusion of both InO and blinatumomab in the frontline setting that is driving these gains, or would enough patients derive benefit if one or both drugs were reserved for use in the salvage setting to offset the apparent advantages of giving both to everyone upfront? Furthermore, if these strategies are implemented broadly, they would introduce some of the same logistical and financial issues described above but for many more patients. If they become viewed as standard or preferred despite the lack of head-to-head comparisons, centers that cannot or have not implemented these immunotherapy-based strategies would be left behind. Importantly, there are some efforts underway that may help address some of these questions while enough in our field consider them unanswered.52,53

Conclusions

The advances made to the treatment of adults with ALL in the last 10 years have been remarkable. Although our field should be proud of these accomplishments and the impact they have had on patients, we must also be mindful of how we bring these incredible therapies and technologies to everyone affected by this disease. It is my contention that we can still push our field forward while being better stewards of finite resources, particularly when many medical centers are facing difficult choices over how they use diminishing funds and staff. I also believe some of these concepts could apply more broadly across hematology/oncology. By doing so, we may have an even greater impact on these challenging diseases and the diverse range of communities they afflict.

Authorship

Contribution: R.D.C. conceived of the topic, wrote the manuscript, and created the tables and figure.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.D.C. reports research funding from Amgen, Kite/Gilead, Incyte, Merck, Pfizer, Servier, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; consultancy fees/honoraria from Autolus, Amgen, Jazz, Kite/Gilead, and Pfizer; membership on a board or advisory committee for Autolus and PeproMene Bio; and reports that their spouse was employed by and owned stock in Seagen.

Correspondence: Ryan D. Cassaday, University of Washington, 825 Eastlake Ave E, Mailstop J4-200, Seattle, WA 98109-1023; email: cassaday@uw.edu.