Key Points

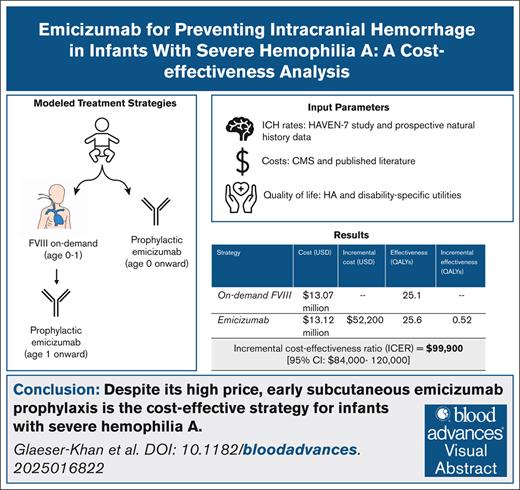

Despite its high price, subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis is the cost-effective strategy for infants with severe HA.

Cost-effectiveness is achieved due to reduction of ICH incidence and its sequela with emicizumab prophylaxis in the first year of life.

Visual Abstract

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and resulting neurologic disability are severe complications for a subset of infants with severe hemophilia A (HA). Although prophylactic factor replacement reduces bleeding risk, it is typically delayed until after age 1 year due to risks associated with central venous access placement. Emicizumab, a subcutaneous activated factor VIII (FVIII) mimetic, has demonstrated safety and efficacy in preventing ICH in infants aged <12 months in the HAVEN 7 trial. Despite its high cost, the cost-effectiveness of emicizumab prophylaxis initiated during the first year of life for infants with severe HA is not known. We developed a Markov cohort model to compare emicizumab prophylaxis to standard care (no prophylaxis) in infants aged 0 to 1 year with severe HA without FVIII inhibitors. The analysis was conducted from a US societal perspective over a lifetime horizon across all accepted willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds. The primary outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in US dollar per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). Emicizumab prophylaxis and standard care accrued 25.6 and 25.1 QALYs at costs of $13.12 million and $13.07 million, respectively, resulting in an ICER of $99 900 per QALY (95% credible interval [CI], 84 000-120 000). Scenario analysis examining prophylaxis with low-dose emicizumab resulted in an ICER of $19 600 per QALY (95% CI, 12 000-29 000). Probabilistic sensitivity analyses showed that standard-dose emicizumab is the cost-effective strategy in 100%, 66%, and 0% of 10 000 Monte Carlo iterations at WTP thresholds of $150 000, $104 000, and $50 000 per QALY, respectively, and in 100% across all WTP thresholds for low-dose emicizumab.

Introduction

Hemophilia A (HA) is an X-linked recessive bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). The severity of HA is classified based on FVIII activity levels: severe (<1% FVIII activity), moderate (1%-5%), and mild (5%-40%).1,2 Although all severities of HA are characterized by prolonged bleeding after injury or surgery, individuals with severe and, in some cases, moderate HA also experience spontaneous, life-threatening hemorrhages. Prophylactic IV FVIII concentrate decreases bleeding incidence.3 However, given the required frequency and difficulty of IV infusion, prophylactic FVIII prophylaxis before age 1 year often requires central venous access, which itself carries risk of infection, surgical complications, and line malfunctions.4 Thus, prophylactic FVIII is often started after age 1 year, leaving infants with HA at an elevated risk of bleeding, particularly intracranial hemorrhage (ICH).4,5 According to natural history data, infants with severe HA not on prophylaxis have a 2% to 3% rate of ICH in each of the first and second year of life.6 ICH in a subset of infants with severe HA is fatal or leads to lifelong neurologic disability in a subset of survivors.6,7

To obviate the need for central venous access, the goal in the care of infants and toddlers with severe HA has been to transition away from IV factor prophylaxis toward subcutaneous administration. Emicizumab is a subcutaneous activated FVIII mimetic, approved in 2018 for HA prophylaxis in all ages without inhibitors. The phase 3, open-label HAVEN 7 study showed that emicizumab was safe and effective at preventing ICH in infants with severe HA.8 However, given the expense of emicizumab, affordability concerns have been raised about such an approach, and the cost-effectiveness of such an approach is currently unknown. We sought to fill this gap by evaluating the cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis with emicizumab vs on-demand standard half-life FVIII in the first year of life for males living with severe HA in the United States.

Methods

Model structure

We built a Markov cohort model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of emicizumab prophylaxis compared to no prophylaxis for infants aged 1 month to 1 year with severe HA without FVIII inhibitors. The probability of experiencing an ICH in the first year of life on emicizumab prophylaxis was informed by the HAVEN 7 phase 3b clinical trial,8 whereas the probability of experiencing ICH for infants treated with on-demand FVIII (no prophylaxis) was informed by age- and treatment-specific global natural history data.6,9 We modeled the outcomes of surviving ICH as either surviving without disability or surviving with disability. Hemophilia-specific probabilities of infant death and disability secondary to an ICH event were informed by a published review of ICH and an ambidirectional, international pediatric hemophilia cohort.6,7 After age 1 year, all patients in both strategies in the base case were started on prophylaxis with emicizumab with 0 additional ICH events (ie, there is no comparative differential in clinical events between strategies after age 1 year). The subset of patients who sustained a disabling ICH event during the first year of life face neurologic disability–specific effects, which are documented to include a lower quality of life, higher monthly cost of medical care, and a higher background mortality, as informed by published literature10 (supplemental Material).

Our analysis was conducted from the US societal perspective over a lifetime horizon with a 100% male patient population, in accordance with the patient population of HAVEN 7.8 Transition state cycles were 1 month in duration, as previously used in hemophilia modeling work. The primary outcome was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in US dollar per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), reported nonnormatively across all accepted willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds in the United States. Both costs and health outcomes were discounted by 3% annually, as recommended in the US context.11,12 Our model was constructed using TreeAge Pro Healthcare 2024 (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA). The Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards guideline was implemented when applicable.

Model assumptions

Base-case estimates and ranges for all input parameters used in the model are reported in Table 1. We conservatively assumed that the previously documented proportion of ICH outcomes in children with HA would remain unchanged into adulthood. Specifically, we assumed that an intact neurologic status due to ICH results in complete recovery without any detriment to adult life and a nonintact neurologic status due to ICH in childhood persists throughout the lifetime. In addition, we assumed that all children aged 0 to 1 year not on prophylaxis who sustained an ICH event were then started on prophylaxis without ICH recurrence. Both assumptions were made to conservatively favor the null hypothesis (ie, that emicizumab prophylaxis is not cost-effective). We assumed that pediatric patients with persistent neurologic disabilities have 1 of their parents as a caregiver and that both the patient and their caregiver lose wages during their adult life. Specifically, patients lose wages from age 18 to 65 years, and 1 parent loses wages starting with the ICH event until they turn age 65 years (assuming an average age of first parents of 27.5 years).13 When considering lost wages, we assumed that patients and caregivers work ∼8 hours per day and ∼21 days per month. We evaluated the effect of all assumptions across extensive sensitivity and scenario analyses.

Model input parameters

| Input parameter . | Value . | Probability distribution . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utilities | |||

| Baseline HA utility, prophylaxis | 0.9378-0.0026 × age | β-PERT (varied by ±0.05 from base case) | 14,15,16 |

| Baseline HA utility, no prophylaxis | 0.6705-0.0019 × age | β-PERT (varied by ±0.05 from base case) | 14,15,16 |

| Disutility of infusion, assuming 12 FVIII infusions per month | 0.005 | β-PERT (0.004, 0.006) | 17 |

| Disutility of CVAD infection | 0.045 | β-PERT (0.036, 0.054) | 18 |

| Utilities by mRS | |||

| mRS 0 | 0.936 | 19 | |

| mRS 1 | 0.817 | ||

| mRS 2 | 0.681 | ||

| mRS 3 | 0.558 | ||

| mRS 4 | 0.265 | ||

| mRS 5 | –0.054 | ||

| Utility for no disability/mild disability after ICH, mRS 0-2 | 0.78 | β-PERT (0.63, 0.94) | Calculation (supplemental, see “Disability-specific utilities”) |

| Utility for disability after ICH, mRS 3-5 | 0.35 | β-PERT (0.28, 0.42) | Calculation (supplemental, see “Disability-specific utilities”) |

| Transition probabilities | |||

| Probability of ICH on emicizumab, yearly, age 0-1 year | 0 | β-PERT (0, 0.00000001) | 6,9 |

| Probability of ICH on standard of care, yearly, age 0-1 year | 0.024 | β-PERT (varied by ±20%) | 6,9 |

| Probability of death after ICH, age 0-1 year | 0.0714 | β-PERT (0.05712, 0.08568) | 7 |

| Probability of disability after ICH, age 0-1 year | 0.38 | β-PERT (0.304, 0.456) | 7 |

| Background mortality for males | Age dependent | US life tables | |

| Disability mortality hazard, relative to background mortality | 151% | Fixed | 10 |

| Distribution of outcomes across the mRS after ICH, 3 months after ICH | |||

| mRS 0 | 0.038 (5/132) | 20 | |

| mRS 1 | 0.22 (29/132) | ||

| mRS 2 | 0.129 (17/132) | ||

| mRS 3 | 0.234 (31/132) | ||

| mRS 4 | 0.318 (42/132) | ||

| mRS 5 | 0.061 (8/132) | ||

| Probability of CVAD infection | 0.0196 | β-PERT (0.0131, 0.0287) | 4 |

| Costs | |||

| Cost of emicizumab prophylaxis, monthly per kg | $610.10 | Fixed | CMS |

| Cost of Advate prophylaxis, monthly per kg | $454.2 | Fixed | CMS |

| Male body weight, kg | Age dependent | 21 (age 0-2 years) 22 (age 2-20 years) 23 (age 20-100 years) | |

| Cost of treating ICH | |||

| Cost of Advate to treat ICH, per kg | $3 179.40 | Fixed | CMS |

| Inpatient costs of ICH | $14 230.77 | γ (225, 63.2) | CMS |

| General population male yearly health care expenditures | Age dependent | γ (varied by ±20% from base case) | MEPS |

| Health care expenditures by mRS, 2010-2014 | |||

| mRS 0 | $10 500 | 24 | |

| mRS 1 | $10 500 | ||

| mRS 2 | $10 500 | ||

| mRS 3 | $11 484 | ||

| mRS 4 | $11 484 | ||

| mRS 5 | $11 484 | ||

| Average baseline health care expenditures for males, 2010-2014 | $6 870 | Fixed | MEPS |

| Post-ICH no-disability/mild-disability baseline cost multiplier | 1.53 | Fixed | Calculation (supplemental, see “cost multipliers”) |

| Post-ICH disability baseline cost multiplier | 1.67 | Fixed | Calculation (supplemental, see “cost multipliers”) |

| Hourly wage for a working adult | $31.48 | Fixed | 25 |

| Cost of death: child, adjusted to 2024 USD | $124 530 | γ (225.1, 553.2) | 26 |

| Cost of death: adult, adjusted to 2024 USD | $64 117 | γ (225.5, 284.4) | 27 |

| Cost of CVAD insertion | $1 144.1 | Fixed | CMS |

| Cost of CVAD removal | $214.46 | Fixed | CMS |

| Input parameter . | Value . | Probability distribution . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Utilities | |||

| Baseline HA utility, prophylaxis | 0.9378-0.0026 × age | β-PERT (varied by ±0.05 from base case) | 14,15,16 |

| Baseline HA utility, no prophylaxis | 0.6705-0.0019 × age | β-PERT (varied by ±0.05 from base case) | 14,15,16 |

| Disutility of infusion, assuming 12 FVIII infusions per month | 0.005 | β-PERT (0.004, 0.006) | 17 |

| Disutility of CVAD infection | 0.045 | β-PERT (0.036, 0.054) | 18 |

| Utilities by mRS | |||

| mRS 0 | 0.936 | 19 | |

| mRS 1 | 0.817 | ||

| mRS 2 | 0.681 | ||

| mRS 3 | 0.558 | ||

| mRS 4 | 0.265 | ||

| mRS 5 | –0.054 | ||

| Utility for no disability/mild disability after ICH, mRS 0-2 | 0.78 | β-PERT (0.63, 0.94) | Calculation (supplemental, see “Disability-specific utilities”) |

| Utility for disability after ICH, mRS 3-5 | 0.35 | β-PERT (0.28, 0.42) | Calculation (supplemental, see “Disability-specific utilities”) |

| Transition probabilities | |||

| Probability of ICH on emicizumab, yearly, age 0-1 year | 0 | β-PERT (0, 0.00000001) | 6,9 |

| Probability of ICH on standard of care, yearly, age 0-1 year | 0.024 | β-PERT (varied by ±20%) | 6,9 |

| Probability of death after ICH, age 0-1 year | 0.0714 | β-PERT (0.05712, 0.08568) | 7 |

| Probability of disability after ICH, age 0-1 year | 0.38 | β-PERT (0.304, 0.456) | 7 |

| Background mortality for males | Age dependent | US life tables | |

| Disability mortality hazard, relative to background mortality | 151% | Fixed | 10 |

| Distribution of outcomes across the mRS after ICH, 3 months after ICH | |||

| mRS 0 | 0.038 (5/132) | 20 | |

| mRS 1 | 0.22 (29/132) | ||

| mRS 2 | 0.129 (17/132) | ||

| mRS 3 | 0.234 (31/132) | ||

| mRS 4 | 0.318 (42/132) | ||

| mRS 5 | 0.061 (8/132) | ||

| Probability of CVAD infection | 0.0196 | β-PERT (0.0131, 0.0287) | 4 |

| Costs | |||

| Cost of emicizumab prophylaxis, monthly per kg | $610.10 | Fixed | CMS |

| Cost of Advate prophylaxis, monthly per kg | $454.2 | Fixed | CMS |

| Male body weight, kg | Age dependent | 21 (age 0-2 years) 22 (age 2-20 years) 23 (age 20-100 years) | |

| Cost of treating ICH | |||

| Cost of Advate to treat ICH, per kg | $3 179.40 | Fixed | CMS |

| Inpatient costs of ICH | $14 230.77 | γ (225, 63.2) | CMS |

| General population male yearly health care expenditures | Age dependent | γ (varied by ±20% from base case) | MEPS |

| Health care expenditures by mRS, 2010-2014 | |||

| mRS 0 | $10 500 | 24 | |

| mRS 1 | $10 500 | ||

| mRS 2 | $10 500 | ||

| mRS 3 | $11 484 | ||

| mRS 4 | $11 484 | ||

| mRS 5 | $11 484 | ||

| Average baseline health care expenditures for males, 2010-2014 | $6 870 | Fixed | MEPS |

| Post-ICH no-disability/mild-disability baseline cost multiplier | 1.53 | Fixed | Calculation (supplemental, see “cost multipliers”) |

| Post-ICH disability baseline cost multiplier | 1.67 | Fixed | Calculation (supplemental, see “cost multipliers”) |

| Hourly wage for a working adult | $31.48 | Fixed | 25 |

| Cost of death: child, adjusted to 2024 USD | $124 530 | γ (225.1, 553.2) | 26 |

| Cost of death: adult, adjusted to 2024 USD | $64 117 | γ (225.5, 284.4) | 27 |

| Cost of CVAD insertion | $1 144.1 | Fixed | CMS |

| Cost of CVAD removal | $214.46 | Fixed | CMS |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; USD, US dollar.

Costs

Patients in the emicizumab prophylaxis cohort were assumed to start subcutaneous emicizumab at a loading dose of 3 mg/kg weekly, followed by a maintenance dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks. After age 1 year, all patients in both strategies were assumed to receive the same prophylaxis (ie, subcutaneous emicizumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks). Medication prices were sourced from Medicare Average Sales Price Pricing. Age- and sex-specific body weights were sourced from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published literature.21-23 Patients who experienced an ICH were assumed to receive FVIII replacement treatment at a dose of 50 IU/kg twice daily for 14 days, followed by once daily for an additional 14 days, with emicizumab prophylaxis loading administered concomitantly during bleed treatment (ie, to allow maintenance dosing to start at the end of bleed treatment). All patients who experienced an ICH continued on emicizumab prophylaxis after acute bleed treatment. Additional inpatient costs of ICH were sourced from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System using the Medicare severity diagnosis-related group code 808. Our model also assumed differences in increased health resource utilization for the subset of survivors of ICH with sustained neurologic disability (ie, disability status), based on neurologic disability–specific data.24 Baseline age- and sex-specific health care expenditures were sourced from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.28 Neurologic disability status–specific expenditures were derived from prior literature, with patient age and expenditure year matched to baseline age- and sex-specific health care expenditure in Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (supplemental Material).24 For societal costs, we considered productivity losses for patients and their caregivers due to ICH sequelae and premature mortality. We sourced the average hourly wage for a working adult from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.25 All costs were inflated to 2024 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.29

Utilities

Health outcomes estimated by our model were expressed in QALYs, a measure that accounts for both health-related quality of life and length of life. Age-dependent regression-adjusted baseline utilities for patients with severe HA on prophylaxis vs not on prophylaxis were sourced from an EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) survey assessing health utilities of males aged 18 to 35 years with severe hemophilia, as previously used in hemophilia health economic evaluations in the United States and globally.14,15,30,31 The EQ-5D is a preference-based health-related quality-of-life tool used to measure patient-reported health across the dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Disability status–specific utilities were derived from a study mapping the modified Rankin Scale (mRS; a measure of disability after stroke using 6 levels) to the EQ-5D questionnaire.19 We then used data on the distribution of disability status after ICH across the mRS20 to derive utilities for surviving ICH with no or mild neurologic damage (mRS 0-3) and surviving ICH with disability (mRS 4-5; supplemental Material). The disutility of FVIII infusion was sourced from published literature.17

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

We quantified the uncertainty within the parameters of our model with a series of deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSAs). In a series of 1-way deterministic sensitivity analyses, we varied all parameters across their known 95% confidence intervals or, when not known, by ±20% of the absolute point estimate, respectively. We then propagated known uncertainty across all parameters simultaneously in each PSA. We parameterized utilities and transition probabilities with β-PERT distributions and costs with γ distributions, while simultaneously ensuring random draws from each distribution via 10 000 second-order Monte Carlo iterations.

In addition, because there have been several published exploratory reports of lower-dose emicizumab (ranging from 50% to <25% of the published trial dosage) in resource-limited countries in an effort to improve access to emicizumab,32-34 we examined a scenario analysis for the cost-effectiveness of low-dose emicizumab (1.5 mg/kg every 2 weeks; 50% of published trial dosing), assuming noninferiority of the lower prophylaxis dose in preventing ICH. In addition, we examined a second scenario analysis in which patients who experienced an ICH initiate prophylaxis with standard half-life (SHL) (Advate at a dose of 25 IU/kg 3 times a week), rather than emicizumab prophylaxis after ICH treatment. This included consideration of central venous access device (CVAD) placement, documented to increase treatment costs and patient burden.4,35 The probability of developing an infection secondary to CVAD use was based on a prior meta-analysis that reported a pooled incidence of 0.66 per 1000 CVAD days (confidence interval, 0.44-0.97).4 The cost of CVAD removal and insertion was sourced from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services price (current procedure terminology 36560 and 36590), and disutility of CVAD complications was informed by prior literature.18 In this scenario, all patients in both strategies were started on (or continued) prophylaxis with SHL, rather than emicizumab. Finally, we evaluated a scenario analysis that considered dose wastage for infants due to available vial sizes of emicizumab in the age 0- to 1-year period only (after age 1 year, there are no differences in prophylaxis between the strategies).

Results

Base case and scenario analysis

The estimated total cost, QALYs, and ICERs associated with each scenario are reported in Table 2. In the base case, emicizumab prophylaxis vs standard care accrued 25.6 and 25.1 QALYs across the life span at costs of $13.12 million and $13.07 million, respectively. The ICER for emicizumab was $99 900 per QALY (95% credible interval [CI], 84 000-120 000). When emicizumab dose was reduced by 50%, the ICER was $19 600 per QALY (95% CI, 12 000-29 000). In a scenario assuming prophylaxis with SHL after ICH treatment (and onward beyond age 1 year in both strategies), the ICER was $99 700 per QALY (95% CI, 83 000-121 000). When accounting for drug waste dose, the ICER increased to $126 300 per QALY (95% CI, 107 000-151 000), which remains well below accepted WTP thresholds in the United States.

Base case, scenario, and PSAs

| Strategy . | Cost, $ (USD) . | Incremental cost, $ (USD) . | Effectiveness, QALYs . | Incremental effectiveness, QALYs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base-case analysis | ||||

| Standard care | 13 070 300 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 13 122 500 | 52 200 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $99 900 per QALY (95% CI, 84 000-120 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, 50% emicizumab dose reduction | ||||

| Standard care | 6 648 800 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 6 659 100 | 10 300 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $19 600 per QALY (95% CI, 12 000-29 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, standard half-life prophylaxis after ICH and age 1 year | ||||

| Standard care | 9 780 700 | 23.4 | ||

| Emicizumab | 9 832 500 | 51 800 | 23.9 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $99 700 per QALY (95% CI, 83 000-121 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, emicizumab vial wastage in age 0- to 1-year period | ||||

| Standard care | 13 070 400 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 13 136 400 | 66 000 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $126 300 per QALY (95% CI, 107 000-151 000) | ||||

| Strategy . | Cost, $ (USD) . | Incremental cost, $ (USD) . | Effectiveness, QALYs . | Incremental effectiveness, QALYs . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base-case analysis | ||||

| Standard care | 13 070 300 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 13 122 500 | 52 200 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $99 900 per QALY (95% CI, 84 000-120 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, 50% emicizumab dose reduction | ||||

| Standard care | 6 648 800 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 6 659 100 | 10 300 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $19 600 per QALY (95% CI, 12 000-29 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, standard half-life prophylaxis after ICH and age 1 year | ||||

| Standard care | 9 780 700 | 23.4 | ||

| Emicizumab | 9 832 500 | 51 800 | 23.9 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $99 700 per QALY (95% CI, 83 000-121 000) | ||||

| Scenario analysis, emicizumab vial wastage in age 0- to 1-year period | ||||

| Standard care | 13 070 400 | 25.1 | ||

| Emicizumab | 13 136 400 | 66 000 | 25.6 | 0.52 |

| ICER, $126 300 per QALY (95% CI, 107 000-151 000) | ||||

Sensitivity analyses

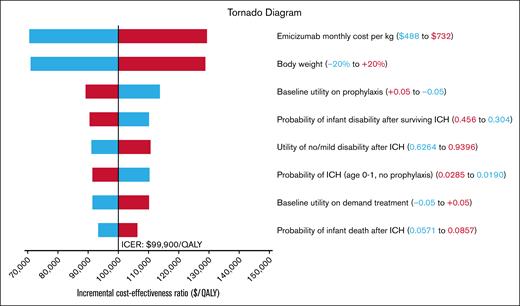

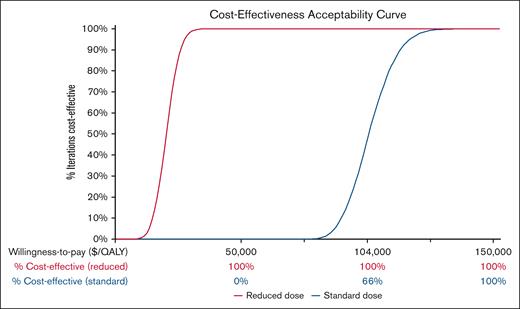

Across 1-way sensitivity analyses, the ICER for emicizumab was most sensitive to pediatric age-specific body weight, the cost of emicizumab, and the probability of ICH in the first year of life for patients not on prophylaxis. No parameter variation increased the ICER above $150 000 per QALY (Figure 1). In PSAs across WTP thresholds of $150 000, $104 000, and $50 000 per QALY for each of the base case (regular dose) and scenario analysis (reduced dose), emicizumab was favored over standard care in 100%, 66%, and 0% for the base case and 100%, 100%, and 100% for the scenario analysis, of 10 000 Monte Carlo iterations, respectively (Figure 2).

One-way deterministic sensitivity analyses. Each row illustrates analytic outcome (ie, change in ICER) results when 1 parameter is varied across its range. Ranges used in analyses are detailed in Table 1. Blue denotes ICER changes associated with lower values, whereas red denotes ICER changes associated with higher values.

One-way deterministic sensitivity analyses. Each row illustrates analytic outcome (ie, change in ICER) results when 1 parameter is varied across its range. Ranges used in analyses are detailed in Table 1. Blue denotes ICER changes associated with lower values, whereas red denotes ICER changes associated with higher values.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of PSAs. Across WTPs of $150 000, $104 000, and $50 000 per QALY, emicizumab favored over standard care in 100%, 66%, and 0% of 10 000 Monte Carlo iterations, respectively. In the low-dose emicizumab scenario, emicizumab is favored in 100% of iterations across all accepted WTPs in the United States.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve of PSAs. Across WTPs of $150 000, $104 000, and $50 000 per QALY, emicizumab favored over standard care in 100%, 66%, and 0% of 10 000 Monte Carlo iterations, respectively. In the low-dose emicizumab scenario, emicizumab is favored in 100% of iterations across all accepted WTPs in the United States.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first cost-effectiveness analysis of emicizumab in young children with severe HA. To support fully informed and transparent decision-making, we reported our cost-effectiveness results across a range of WTP thresholds rather than relying on a single benchmark. Despite conservative assumptions, we show that emicizumab prophylaxis in the first year of life is cost-effective due to ICH prevention in a subset of infants with severe HA at the most recently derived WTP threshold point estimate ($104 000 per QALY).36 These results are robust and consistent across all deterministic sensitivity analyses and PSAs. Across scenario analyses, we show that low-dose emicizumab prophylaxis is cost-effective across all accepted WTP thresholds in the United States, and scenarios accounting for FVIII prophylaxis as standard care and vial wastage do not change our conclusion.

This analysis advances the literature in several ways. Our model adds to a growing body of evidence from clinical trials and real-world data favoring the use of emicizumab prophylaxis in infants with severe HA to prevent ICH.8,37,38 This is, to our knowledge, the first study to quantify the projected lifetime benefits of such an approach. Previous economic evaluations in infants with HA have mainly focused on comparing FVIII prophylaxis with on-demand treatment without reaching a clear consensus on the cost-effectiveness of FVIII prophylaxis.18,39,40 Using subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis before age 1 year avoids the need for central venous access, which is typically required for FVIII prophylaxis in this age group and carries risks.4 Emicizumab significantly reduces the risk of ICH compared to not being on prophylaxis,6,8 which is particularly relevant in the first year of life, when it is standard practice for patients to use an on-demand treatment strategy due to venous access issues. As such, emicizumab should be strongly considered as an option for prophylaxis in the first year of life for patients with severe HA.

Although our findings support the early initiation of emicizumab prophylaxis from both clinical and economic perspectives, several real-world barriers may affect its implementation. In cases of HA without a known family history, diagnosis is often delayed beyond the neonatal period, limiting opportunities for early prophylaxis.9 This highlights the need for strategies to improve early diagnosis in this population. Even when diagnosed early, caregivers may hesitate to initiate prophylaxis due to concerns about long-term safety or unnecessary treatment.41,42 Addressing these concerns through shared decision-making will be critical to supporting early implementation in routine practice.

Given the known expense and limited availability of factor products in the care of people living with hemophilia in resource-constrained settings, these results should be considered within the context of global health equity. Although emicizumab is cost-effective across the lifetime at a WTP threshold of $150 000 per QALY, prophylaxis in the first year of life still requires a high upfront cost, which may not be feasible in a variety of contexts, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Assuming noninferiority with respect to ICH risk of 50% reduced-dose emicizumab, we show that the ICER point estimate drops below even the lowest accepted WTP threshold in the United States. However, research building on and extending the preliminary evidence for the efficacy of dose-reduced emicizumab is necessary, particularly in the 0- to 2-year age group in whom standard doses achieve higher plasma levels than older children and adults.32,43,44

This study has several strengths. First, our analysis is based on phase 3b clinical trial data evaluating the efficacy of emicizumab in infants with severe HA, and prospective natural history data inform the standard care comparison. Second, we used prophylaxis-, treatment-, and population-specific utilities. Third, our study estimates societal costs in terms of productivity losses for patients with lifelong disability (and their parents) as well as lost productivity from premature mortality.10,25,45 Finally, patients in both arms of our model are managed with the same prophylactic treatment after age 1 year without a differential effect on clinical outcomes after age 1 year, isolating specifically the lifelong benefit of emicizumab during the age 1-month to 1-year time period. This is particularly important given brisk advances in the HA prophylactic armamentarium; thus, a change to another product for prophylaxis in the future for the age ≥1 period would not change our conclusion.

We also recognize several limitations of our study, as well as areas for future research. First, the disability utilities we use are derived from an adult ICH-specific population. This limitation, which we addressed in extensive sensitivity analyses, nevertheless highlights a need for qualitative decision science research in the HA population across the life span. Second, this model does not consider bleeds other than ICH (eg, joint bleeds, which were reduced by emicizumab in the HAVEN-7 study compared to rates derived from natural history data). Because joint bleeds are reduced by emicizumab, the ICER for emicizumab is likely to be lower than what we report in this study. Third, this model does not consider the increased risk of developing inhibitors associated with being treated with FVIII concentrate (such as in the first year of life in the control arm of our model’s second scenario).46,47 Because developing inhibitors is associated with marked increase in morbidity and a significant economic burden,48-50 the ICER for emicizumab is again likely to be lower than what we report in this study. Fourth, we recognize that there are barriers to implementing early prophylaxis with emicizumab not accounted for in this model. In cases of HA without a known family history (∼30% of cases), diagnosis is often delayed, resulting in delayed prophylaxis despite availability of safe and effective prophylactic options. Fifth, our analysis is based exclusively on US pricing data, which limits generalizability given the significant international variation in the costs of emicizumab and clotting factor concentrate. Future research incorporating country-specific pricing could improve the applicability of the findings across different settings. Finally, as noted in a recent systematic review, significant heterogeneity in modeling methods, lack of clarity around assumptions and justification for input parameters, normative data presentation, and previously reported bias in cost-effectiveness studies supported by industry highlight the difficulty of comparison across study results in the hemophilia arena.51 Although our model addressed these shortcomings by being free of industry funding, reporting nonnormatively across all accepted WTP thresholds over a lifetime horizon from a societal perspective, any model is nevertheless a simplification of clinical practice for the purpose of comparing the value of emicizumab prophylaxis vs no emicizumab prophylaxis in the first year of life.

In summary, we conducted, to our knowledge, the first cost-effectiveness analysis of emicizumab vs standard care in the first year of life in the HA population. We found that emicizumab is the cost-effective strategy at WTP thresholds of $100 000 to $150 000 per QALY. When we considered a 50% dose reduction, emicizumab is cost-effective across all accepted WTP thresholds in the United States. Further qualitative health care decision science research is needed in this population across the life span, as well as research to evaluate the efficacy of dose-reduced emicizumab, especially in individuals aged <2 years, given the higher emicizumab plasma levels with routine dosing in this population than older individuals living with severe HA.

Acknowledgments

G.G. is supported by the NOMIS Foundation, the Frederick A. DeLuca Foundation, Yale Cancer Center, the Yale Bunker Endowment; National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 1K01 HL175220; and NIH, National Cancer Institute research grant CA-016359.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources. This manuscript is the result of funding in whole or in part by the NIH. It is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy. Through acceptance of this federal funding, NIH has been given a right to make this article publicly available in PubMed Central upon the Official Date of Publication, as defined by NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: S.G.-K., S.I., and G.G. conceived the study design; and all authors wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: In the past 3 years, H.M.K. has received options for Element Science and Identifeye and payments from F-Prime for advisory roles; was a cofounder of and held equity in Hugo Health; is a cofounder of and holds equity in Refactor Health and Ensight-AI; and is associated with research contracts through Yale University from Janssen, Kenvue, Novartis, and Pfizer. S.E.C. has consulted for BioMarin, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and reports research funds (to institution) from Spark Therapeutics and Sanofi. A.C. has served as a consultant for MingSight, New York Blood Center, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Synergy; and reports authorship royalties from UpToDate. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: George Goshua, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar St, New Haven, CT 06520; email: george.goshua@yale.edu.

References

Author notes

S.G.-K. and S.I. are joint first authors.

Data used in this study are from publicly sourced research, are outlined within the article, and available on request from the corresponding author, George Goshua (george.goshua@yale.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.