Key Points

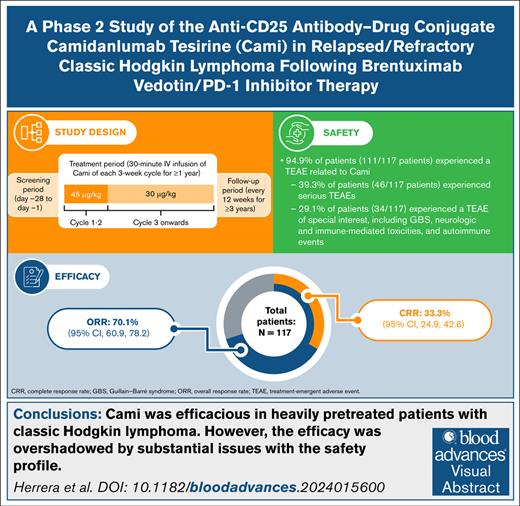

Cami produced an overall and complete response rate of 70% and 33%, respectively, in relapsed/refractory cHL.

Substantial safety issues, including skin toxicities and neurologic immune-related adverse events, were observed with Cami.

Visual Abstract

Outcomes in classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) have steadily improved; however, additional therapies are needed for patients who relapse or do not respond to novel agents. Here, we report the efficacy and safety of camidanlumab tesirine (Cami), an anti-CD25 antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with relapsed/refractory cHL after brentuximab vedotin/programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor therapies from the phase 2 ADCT-301-201 study. Eligible patients were adults with cHL who had received ≥3 previous lines of systemic therapy (or ≥2 if ineligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant). Patients received 45 μg/kg Cami (IV, once every 3 weeks) in cycles 1 to 2, followed by 30 μg/kg IV once every 3 weeks for ≤1 year. The primary end point was overall response rate (ORR) per 2014 Lugano classification. Secondary end points included complete response rate (CRR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). In total, 117 patients were enrolled with a median age of 37.0 years (range, 19-87). The ORR was 70.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 60.9-78.2), with a CRR of 33.3% (95% CI, 24.9-42.6). The median PFS was 9.13 months (95% CI, 5.3-15.0); median OS was not reached. Thirty-three (28.2%) patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-emergent adverse events; the most common reasons were skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (n = 10 [8.5%] patients), infections and infestations (n = 5 [4.3%]), and nervous systems disorders (n = 5 [4.3%]). Guillain-Barré–type or polyradiculopathy-type events occurred in 8 (6.8%) patients. Cami was efficacious in this heavily pretreated population; however, the efficacy was overshadowed by substantial issues with the safety profile. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT04052997.

Introduction

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) typically presents in young adults and accounts for ∼10% of cases of newly diagnosed lymphoma.1-4 Although outcomes have steadily improved over the years, ∼10% to 20% of patients with cHL do not respond to treatment or experience relapse.5 There is no consensus on preferred late-line salvage regimens, and choice of therapy depends on previous treatments the patient has already received.6,7 Patients who have previously received brentuximab vedotin (BV) and programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor therapies have limited options, and novel agents are needed to improve patient outcomes.8-11

Camidanlumab tesirine (Cami) is an anti-CD25 antibody-drug conjugate with a pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) payload (SG3199) that has demonstrated encouraging efficacy as a single agent in a phase 1 study in relapsed/refractory (R/R) lymphomas.12 The maximum tolerated dose was not reached; the dose levels of 45 μg/kg and 30 μg/kg were identified as the recommended doses for expansion for patients with cHL. The most common observed adverse events (AEs), such as elevated liver enzymes, rash, fatigue, edema, and effusion, were consistent with other studies using the SG3199 PBD payload and were generally reversible and manageable with dose delays or reductions.12-14 Of 77 patients with cHL, 5 (∼6%) developed Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) or polyradiculopathy after treatment with Cami. Further investigation of these events demonstrated that GBS events were not associated with dose, cycle number, or previous immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.12,15 In terms of efficacy, Cami showed high response rates in a heavily pretreated population. Of the 37 evaluable patients with R/R cHL who received a dose of 45 μg/kg, the overall response rate (ORR) was 86.5%, of whom 48.6% had a complete response (CR).12

Here, we report results from the ADCT-301-201 phase 2 study, which was conducted to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of Cami in R/R cHL.

Methods

Study oversight

ADCT-301-201 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04052997) was an open-label, single-arm, multicenter study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Cami in patients with R/R cHL conducted at 73 sites in 11 countries (supplemental Table 1).

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years (or ≥16 years for sites in the United States); had a diagnosis of cHL with measurable disease per the 2014 Lugano classification16; received ≥3 previous lines of systemic therapy, including hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), BV, checkpoint inhibitors approved for cHL, or ≥2 previous lines in patients who were ineligible for HSCT; had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status grade of 0 to 2; and had adequate organ function (absolute neutrophil count of ≥1.0 × 103/μL, platelet count of ≥75 × 103/μL without transfusion in the past 2 weeks; alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, or gamma-glutamyl transferase of ≤2.5 × the upper limit of normal [ULN] without liver involvement [alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase of ≤5.0 × ULN in cases of liver involvement]; total bilirubin of ≤1.5 × ULN [total bilirubin of ≤3.0 × ULN with direct bilirubin of ≤1.5 × ULN in patients with known Gilbert syndrome]; and blood creatinine ≤3.0 × ULN or calculated creatinine clearance of ≥30 mL/min by the Cockcroft-Gault equation17). Patients were excluded in cases of history of hypersensitivity or positive serum human antidrug antibody to a CD25 antibody; allogeneic or autologous HSCT ≤60 days before the start of study drug; active graft-versus-host disease, except for nonneurologic symptoms as a manifestation of grade ≤1 chronic graft-versus-host disease; post-HSCT lymphoproliferative disorders; active second primary malignancy (other than nonmelanoma skin cancers, nonmetastatic prostate cancer, in situ cervical cancer, and ductal or lobular carcinoma in situ of the breast); history of symptomatic autoimmune disease; history of neuropathy considered of autoimmune origin or cHL with central nervous system involvement; history of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis; or other significant medical comorbidities.

Study treatment and procedures

Patients received 45 μg/kg Cami (IV, once every 3 weeks) in cycles 1 to 2 (21-day cycles), followed by 30 μg/kg IV once every 3 weeks for subsequent cycles for ≤1 year or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or other discontinuation criteria. Patients who experienced clinical benefit could continue the treatment past 1 year on a case-by-case basis. Patients were premedicated with dexamethasone (4 mg orally, twice daily) to mitigate PBD-associated toxicities the day before Cami infusion, the day of the Cami infusion (≥2 hours before infusion if it was not possible to give the day before; otherwise, any time before infusion), and the day after each Cami infusion, unless contraindicated. Disease assessments used positron emission tomography–computed tomography and were conducted at screening, at 6 weeks and 12 weeks after the first infusion, every 9 weeks throughout treatment, at the end of treatment, every 12 weeks for 1 year after the end of treatment, and then every 6 months until disease progression or initiation of other anticancer therapy except for HSCT or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

Outcomes

The primary end point of the ADCT-301-201 study was ORR according to the 2014 Lugano classification,16 as determined by central review in all treated patients. Central imaging review was performed by 2 blinded independent reviewers with adjudication by a third blinded independent reviewer in cases of discordance. Secondary end points included the CR rate (CRR), duration of response (DOR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival. The safety of Cami was assessed via frequency and severity of AEs, as well as changes from baseline of safety laboratory values, vital signs, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, and 12-lead electrocardiograms. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were defined as an AE that occurred or worsened in the period extending from the first dose of Cami to either 30 days after the last dose of Cami in this study or the start of a new anticancer therapy/procedure. Non-TEAEs were defined as occurring >30 days after the last dose of Cami or after the start of subsequent anticancer therapy. The following AEs, regardless of seriousness or causality, were considered AEs of special interest (AESIs): GBS (including variants such as acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy), polyradiculopathy, autonomic nervous system imbalance, nerve palsy, grade ≥3 neurologic- and immune-mediated toxicities, and autoimmune events. Rashes were not defined as AESIs because they are well-described toxicities of PBD dimers,13 with the exception of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, exfoliative dermatitis, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. A protocol specified interim safety enrollment pause was triggered after the occurrence of ≥2 cases of GBS or other relevant severe neurologic toxicity. During the safety pause, a detailed independent review was performed by the data and safety monitoring board and it was recommended that the study resume. The impact of Cami on health-related quality of life was assessed via European Quality-of-Life 5-Dimension 5-Level and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, General, including the lymphoma-specific subscale questionnaires. CD25 expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and histoscore (H-score) in tumor biopsy samples. H-score was reported as a composite score of the percent of positive cells and the degree of positivity as follows: negative (0), weakly (1+), moderately (2+), and strongly (3+) stained membranes. The H-score, with a potential range of 0 to 300, was calculated as follows: H-score = [(1 × % weakly stained cells) + (2 × % moderately stained cells) + (3 × % strongly stained cells)].18 Additionally, soluble CD25 (sCD25) and CCL17 levels were measured in serum via immunoassays; patients with values falling outside of quantifications levels were excluded from analyses.

Statistical methods

A sample size of 100 was estimated to provide >98% power to distinguish between an active therapy with a 55% true response rate and a therapy with a response rate of <35% with a 1-sided α of .025. The all-treated population consisted of all patients who received ≥1 dose of Cami. Time-to-event end points were analyzed via the Kaplan-Meier method. Responses were analyzed via percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences between biomarker levels in responders and nonresponders were assessed via box plots and statistical significance of differences was inferred using Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction (threshold for significance, P = .05). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were performed to evaluate the predictive potential of biomarker variables. Area under the curve and the maximum Youden index (0-1) were used to measure the sensitivity and specificity of the predictive responses, respectively. Biomarker and ROC analyses were performed using the statistical program R, version 4.3.1, packages stats and pROC.

All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol and amendments were approved by the appropriate institutional review board for each study site. The study was conducted according to good clinical practice, as outlined by the International Council for Harmonisation, except for 1 serious breach in which the sponsor recommended implementation of a prolonged contraception period (9.5 months instead of 6.5 months for women and 6.5 months instead of 16 weeks for men) before obtaining regulatory approval of this change. This change was later included within a protocol amendment, which was approved by regulatory bodies of all participating countries.

Results

Patients

In total, 117 patients were enrolled in ADCT-301-201 and received ≥1 dose of Cami (Figure 1). The median age was 37.0 years (range, 19-87), and the median number of previous lines of systemic therapy was 6 (range, 3-19). Thirty-six (30.8%) patients relapsed after the last previous line of therapy, and 66 (56.4%) patients were refractory to the last previous line of therapy (Table 1). One patient was included in the all-treated population who did not receive previous BV treatment; this was recorded as a protocol deviation. The median follow-up was 20.1 months (range, 1.2-39.4). Among all patients, the median treatment duration was 85.0 days (range, 1-349) and the median number of treatment cycles was 5.0 (range, 1-15). Fifty-eight (49.6%) patients reported ≥1 dose delay, whereas 22 (18.8%) reported ≥1 dose decrease. The most common primary reasons for treatment discontinuation were disease progression (48 [41.0%] patients), unacceptable toxicity (34 [29.1%] patients), and transition to transplant (14 [12.0%] patients; Figure 1). After discontinuing Cami treatment, 18 (15.4%) patients received HSCT without any intervening anticancer therapy (allogeneic, 14 [12.0%] patients; autologous, 4 [3.4%] patients). After the completion of planned accrual, the ADCT-301-201 study was stopped by the sponsor, with the data cutoff date of 27 January 2023, because the data were considered mature, and continued data collection was not expected to substantially affect the overall conclusions of the study. All ongoing patients were in follow-up at that time. For responders, at least 20 months had elapsed since their initial response.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics of the all-treated population

| Characteristic . | N = 117 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 73 (62.4) |

| Female | 44 (37.6) |

| Age, median (range), y | 37.0 (19-87) |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| <60 years | 91 (77.8) |

| ≥60 years | 26 (22.2) |

| Region, n (%) | |

| North America | 56 (47.9) |

| Europe | 61 (52.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 101 (86.3) |

| Black or African American | 5 (4.3) |

| Asian | 3 (2.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (4.3) |

| Missing | 2 (1.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (6.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 104 (88.9) |

| Missing | 6 (5.1) |

| ECOG performance status score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 64 (54.7) |

| 1 | 47 (40.2) |

| 2 | 6 (5.1) |

| Extranodal, n (%) | 47 (40.2) |

| Constitutional symptoms, n (%) | |

| Absence of B symptoms | 62 (53.0) |

| B symptoms | 50 (42.7) |

| Missing | 5 (4.3) |

| Disease stage as study entry, n (%) | |

| I/II | 28 (23.9) |

| III/IV | 89 (76.1) |

| Previous systemic therapies, median (range) | 6.0 (3-19) |

| Previous systemic therapies, n (%) | |

| ≤5 previous lines | 45 (38.5) |

| 6-7 previous lines | 30 (25.6) |

| ≥8 previous lines | 42 (35.9) |

| Previous radiotherapy, n (%) | 55 (47.0) |

| Previous HSCT, n (%) | 74 (63.2) |

| Only autologous | 59 (50.4) |

| Only allogeneic | 3 (2.6) |

| Both | 12 (10.3) |

| None | 43 (36.8) |

| Response to first line of systemic therapy,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 79 (67.5) |

| Refractory† | 29 (24.8) |

| Response to most recent line of systemic therapy,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 36 (30.8) |

| Refractory† | 66 (56.4) |

| Response to last checkpoint inhibitor,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 33 (28.2) |

| Refractory† | 71 (60.7) |

| Characteristic . | N = 117 . |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 73 (62.4) |

| Female | 44 (37.6) |

| Age, median (range), y | 37.0 (19-87) |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| <60 years | 91 (77.8) |

| ≥60 years | 26 (22.2) |

| Region, n (%) | |

| North America | 56 (47.9) |

| Europe | 61 (52.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 101 (86.3) |

| Black or African American | 5 (4.3) |

| Asian | 3 (2.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (4.3) |

| Missing | 2 (1.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (6.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 104 (88.9) |

| Missing | 6 (5.1) |

| ECOG performance status score, n (%) | |

| 0 | 64 (54.7) |

| 1 | 47 (40.2) |

| 2 | 6 (5.1) |

| Extranodal, n (%) | 47 (40.2) |

| Constitutional symptoms, n (%) | |

| Absence of B symptoms | 62 (53.0) |

| B symptoms | 50 (42.7) |

| Missing | 5 (4.3) |

| Disease stage as study entry, n (%) | |

| I/II | 28 (23.9) |

| III/IV | 89 (76.1) |

| Previous systemic therapies, median (range) | 6.0 (3-19) |

| Previous systemic therapies, n (%) | |

| ≤5 previous lines | 45 (38.5) |

| 6-7 previous lines | 30 (25.6) |

| ≥8 previous lines | 42 (35.9) |

| Previous radiotherapy, n (%) | 55 (47.0) |

| Previous HSCT, n (%) | 74 (63.2) |

| Only autologous | 59 (50.4) |

| Only allogeneic | 3 (2.6) |

| Both | 12 (10.3) |

| None | 43 (36.8) |

| Response to first line of systemic therapy,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 79 (67.5) |

| Refractory† | 29 (24.8) |

| Response to most recent line of systemic therapy,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 36 (30.8) |

| Refractory† | 66 (56.4) |

| Response to last checkpoint inhibitor,∗n (%) | |

| Relapse | 33 (28.2) |

| Refractory† | 71 (60.7) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Missing or nonevaluable responses are not included.

Refractory was defined as having a best response to a line of treatment of stable disease or progressive disease.

Efficacy

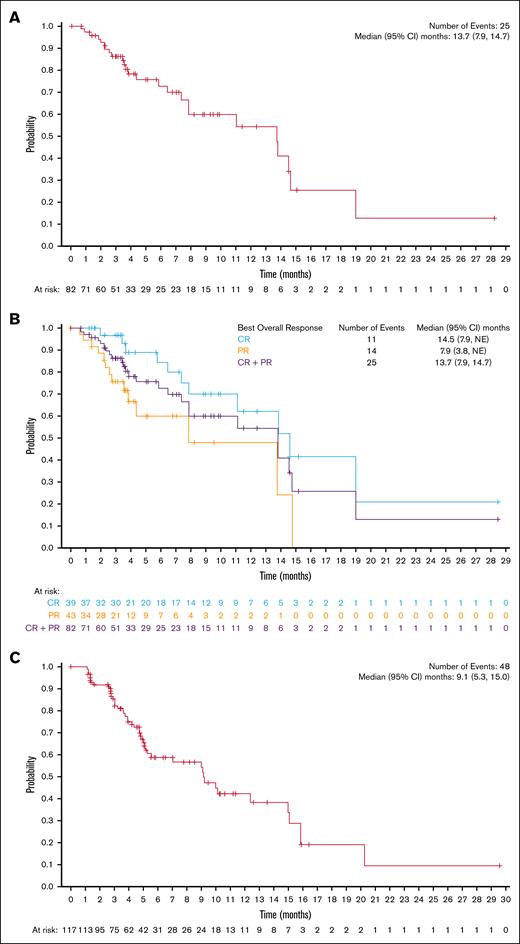

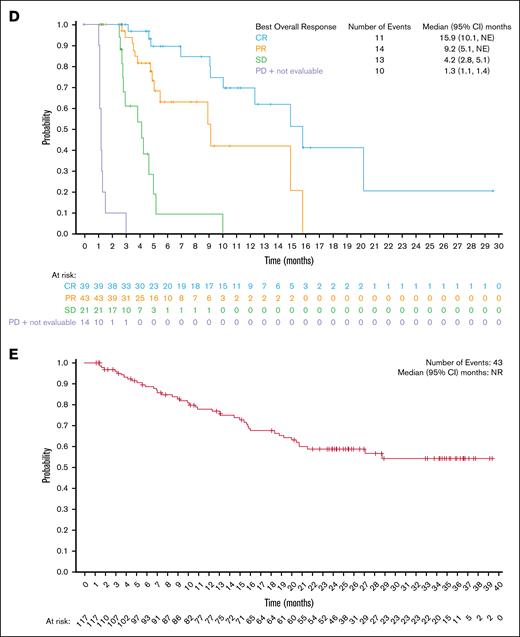

Among all treated patients, the ORR was 70.1% (82/117 patients; 95% CI, 60.9-78.2), and the CRR was 33.3% (39/117 patients; 95% CI, 24.9-42.6; supplemental Table 2). The median DOR was 13.7 months (95% CI, 7.9-14.7; Figure 2A), with a 54.4% (95% CI, 35.8-69.6) probability of maintaining response for 12 months. Among patients with a CR, the median DOR was 14.5 months (95% CI, 7.9 to not estimable [NE]; Figure 2B), with a 62.1% (95% CI, 36.4-79.9) probability of maintaining response for 12 months. The median time to first response (either CR or partial response) was 41.0 days (range, 32-148), whereas the median time to first response of CR was 45.0 days (range, 36-222), and the median time to best overall response was 43.0 days (range, 32-222). The median PFS was 9.1 months (95% CI, 5.3-15.0; Figure 2C). When analyzed by best overall response, the median PFS was 15.9 months (95% CI, 10.1 to NE) for patients who achieved a CR, 9.2 months (95% CI, 5.1 to NE) for patients with a partial response, 4.2 months (95% CI, 2.8-5.1) in patients with stable disease, and 1.3 months (95% CI, 1.1-1.4) for patients with progressive disease or who were not evaluable (Figure 2D). The median overall survival was not reached (95% CI, NE to NE; Figure 2E). The ORR and CRR were generally consistent across clinically relevant subgroups included in the analysis compared with the overall population (Figure 3). Notably, patients who were refractory to frontline treatment had an ORR of 72.4% (95% CI, 52.8-87.3) and a CRR of 34.5% (95% CI, 17.9-54.3); patients who had received ≥8 previous lines of therapy had an ORR of 73.8% (95% CI, 58.0-86.1) and a CRR of 38.1% (95% CI, 23.6-54.4); and patients who had received previous stem cell transplant had an ORR of 74.3% (95% CI, 62.8-83.8) and a CRR of 41.9% (95% CI, 30.5-53.9). Demographic and baseline disease characteristics for North American and European patients are provided in supplemental Table 3.

Estimates of duration of response, PFS, and OS. Kaplan-Meier of (A) DOR in the all-treated population, (B) DOR by best overall response, (C) PFS in the all-treated population, (D) PFS by best overall response, and (E) overall survival in the all-treated population. NR, not reached; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Estimates of duration of response, PFS, and OS. Kaplan-Meier of (A) DOR in the all-treated population, (B) DOR by best overall response, (C) PFS in the all-treated population, (D) PFS by best overall response, and (E) overall survival in the all-treated population. NR, not reached; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Subgroup analyses of response rates. Subgroup analysis of (A) ORR and (B) CRR in the all-treated population.

Subgroup analyses of response rates. Subgroup analysis of (A) ORR and (B) CRR in the all-treated population.

Safety

A summary of TEAEs is given in supplemental Table 4. All Cami infusions, with the exception of 1 that was interrupted owing to a grade 2 infusion-related reaction, were completed and well tolerated; no severe or serious instances of hypersensitivity were reported. Infusion-related reactions of any grade occurred in 5 (4.3%) patients, all grade 1 or 2. The most common TEAEs of any grade were fatigue (45 [38.5%] patients), maculopapular rash (38 [32.5%] patients), and pyrexia (35 [29.9%] patients; Table 2). The most common TEAEs of grade ≥3 were lymphopenia (12 [10.3%] patients), thrombocytopenia (11 [9.4%] patients), and anemia (10 [8.5%] patients; Table 2; supplemental Table 5). A summary of TEAEs reported in patients who received allogeneic transplant before enrollment (n = 15) is given in supplemental Table 6.

Most common TEAEs (any grade, at least 10% incidence; grade 3 or higher, at least 3% incidence) by system organ class and severity in the all-treated population

| Any grade TEAE,∗ n (%) . | N = 117 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 2 . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 92 (78.6) | 29 (24.8) | 26 (22.2) |

| Maculopapular rash | 38 (32.5) | 12 (10.3) | 8 (6.8) |

| Rash | 31 (26.5) | 11 (9.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Pruritus | 28 (23.9) | 6 (5.1) | 4 (3.4) |

| Erythema | 14 (12.0) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (5.1) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 84 (71.8) | 33 (28.2) | 9 (7.7) |

| Fatigue | 45 (38.5) | 19 (16.2) | 5 (4.3) |

| Pyrexia | 35 (29.9) | 7 (6.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Peripheral edema | 14 (12.0) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Chills | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 64 (54.7) | 24 (20.5) | 9 (7.7) |

| Nausea | 32 (27.4) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Constipation | 20 (17.1) | 5 (4.3) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 19 (16.2) | 3 (2.6) | 3 (2.6) |

| Vomiting | 13 (11.1) | 6 (5.1) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (10.3) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Investigations | 56 (47.9) | 18 (15.4) | 19 (16.2) |

| Increased GGT | 20 (17.1) | 9 (7.7) | 6 (5.1) |

| Increased ALT | 15 (12.8) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.6) |

| Increased AST | 14 (12.0) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Increased lipase | 9 (7.7) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (4.3) |

| Increased amylase | 9 (7.7) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.4) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 56 (47.9) | 8 (6.8) | 17 (14.5) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 21 (17.9) | 2 (1.7) | 9 (7.7) |

| Hyperglycemia | 14 (12.0) | 4 (3.4) | 4 (3.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 14 (12.0) | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Decreased appetite | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | 54 (46.2) | 11 (9.4) | 8 (6.8) |

| Headache | 19 (16.2) | 4 (3.4) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| GBS | 4 (3.4) | 0 | 4 (3.4) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 51 (43.6) | 14 (12.0) | 32 (27.4) |

| Anemia | 29 (24.8) | 14 (12.0) | 10 (8.5) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 24 (20.5) | 3 (2.6) | 11 (9.4) |

| Neutropenia | 19 (16.2) | 8 (6.8) | 9 (7.7) |

| Lymphopenia | 18 (15.4) | 2 (1.7) | 12 (10.3) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 39 (33.3) | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) |

| Dyspnea | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| Cough | 12 (10.3) | 3 (2.6) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 38 (32.5) | 12 (10.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| Arthralgia | 19 (16.2) | 8 (6.8) | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 23 (19.7) | 11 (9.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Insomnia | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Endocrine disorders | 22 (18.8) | 15 (12.8) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 12 (10.3) | 7 (6.0) | 0 |

| Any grade TEAE,∗ n (%) . | N = 117 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade 2 . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 92 (78.6) | 29 (24.8) | 26 (22.2) |

| Maculopapular rash | 38 (32.5) | 12 (10.3) | 8 (6.8) |

| Rash | 31 (26.5) | 11 (9.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Pruritus | 28 (23.9) | 6 (5.1) | 4 (3.4) |

| Erythema | 14 (12.0) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (5.1) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 84 (71.8) | 33 (28.2) | 9 (7.7) |

| Fatigue | 45 (38.5) | 19 (16.2) | 5 (4.3) |

| Pyrexia | 35 (29.9) | 7 (6.0) | 1 (0.9) |

| Peripheral edema | 14 (12.0) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Chills | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 64 (54.7) | 24 (20.5) | 9 (7.7) |

| Nausea | 32 (27.4) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Constipation | 20 (17.1) | 5 (4.3) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 19 (16.2) | 3 (2.6) | 3 (2.6) |

| Vomiting | 13 (11.1) | 6 (5.1) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (10.3) | 8 (6.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Investigations | 56 (47.9) | 18 (15.4) | 19 (16.2) |

| Increased GGT | 20 (17.1) | 9 (7.7) | 6 (5.1) |

| Increased ALT | 15 (12.8) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.6) |

| Increased AST | 14 (12.0) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Increased lipase | 9 (7.7) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (4.3) |

| Increased amylase | 9 (7.7) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.4) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 56 (47.9) | 8 (6.8) | 17 (14.5) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 21 (17.9) | 2 (1.7) | 9 (7.7) |

| Hyperglycemia | 14 (12.0) | 4 (3.4) | 4 (3.4) |

| Hypokalemia | 14 (12.0) | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Decreased appetite | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | 54 (46.2) | 11 (9.4) | 8 (6.8) |

| Headache | 19 (16.2) | 4 (3.4) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 12 (10.3) | 2 (1.7) | 0 |

| GBS | 4 (3.4) | 0 | 4 (3.4) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 51 (43.6) | 14 (12.0) | 32 (27.4) |

| Anemia | 29 (24.8) | 14 (12.0) | 10 (8.5) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 24 (20.5) | 3 (2.6) | 11 (9.4) |

| Neutropenia | 19 (16.2) | 8 (6.8) | 9 (7.7) |

| Lymphopenia | 18 (15.4) | 2 (1.7) | 12 (10.3) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 39 (33.3) | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) |

| Dyspnea | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| Cough | 12 (10.3) | 3 (2.6) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 38 (32.5) | 12 (10.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| Arthralgia | 19 (16.2) | 8 (6.8) | 0 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 23 (19.7) | 11 (9.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Insomnia | 16 (13.7) | 5 (4.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Endocrine disorders | 22 (18.8) | 15 (12.8) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 12 (10.3) | 7 (6.0) | 0 |

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate aminotransferase; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

AEs coded using MedDRA version 22.0.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders of any grade were experienced by 92 (78.6%) patients, most commonly maculopapular rash (38 [32.5%] patients), rash (31 [26.5%] patients), pruritus (28 [23.9%] patients), and erythema (14 [12.0%] patients). The median time to onset for skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders of any grade was 39 days (range, 3-302), whereas the median time to onset was 99 days (range, 40-302) for grade ≥3. Thirty-three (28.2%) patients required dose delays, and 12 (10.3%) patients discontinued treatment owing to skin or subcutaneous tissue disorders. The median number of days to resolution of skin toxicity after dose reduction or delay was 32.5 days (range, 8-666). Thirty-seven (31.6%) patients had hepatic events, mainly comprising laboratory abnormalities. The median number of days to resolution of hepatic toxicity after dose reduction or delay was 29.5 days (range, 7-320). Two cases of drug-induced liver injury (both grade 3) were reported (mixed [n = 1]; hepatocellular type [n = 1]); both patients recovered. Fifty-one (43.6%) patients had cytopenias, with grade 4 events occurring in 8 (6.8%) patients.

Three patients died because of TEAEs (respiratory failure after multipathogen infection, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrest/left ventricular failure in 1 patient each), none of which were considered related or possibly related to Cami (supplemental Table 7). Three patients experienced fatal non-TEAEs that were considered related or possibly related to Cami: 1 patient each with sepsis, aplastic anemia, and respiratory failure owing to pneumonia. Overall, 33 (28.2%) patients had TEAE(s) leading to treatment discontinuation. The most common types of TEAEs that led to treatment discontinuation were skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (10 [8.5%] patients), infections and infestations (5 [4.3%] patients), and nervous systems disorders (5 [4.3%] patients).

AESIs

Thirty-nine (33.3%) patients reported an AESI of any grade (Table 3). The most commonly reported posttreatment AESIs (≥2% of patients overall) were hypothyroidism (14 [12.0%] patients), hyperthyroidism (9 [7.7%] patients), thyroiditis (8 [6.8%] patients), GBS (6 [5.1%] patients), noninfectious pneumonitis (4 [3.4%] patients), and autoimmune thyroiditis (3 [2.6%] patients). The median time to manifestation of an AESI of any grade was 78 days (range, 17-264) and the median time to manifestation of grade ≥3 AESIs was 105 days (range, 28-393).

AESI by system organ class in the all-treated population

| AESI,∗ n (%) . | N = 117 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3 . | Grade 4 . | Grade 5 . | Total . | |

| Patients with any AESI | 6 (5.1) | 17 (14.5) | 9 (7.7) | 6 (5.1) | 1 (0.9) | 39 (33.3) |

| Endocrine disorders | 8 (6.8) | 16 (13.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 (20.5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (5.1) | 8 (6.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (12.0) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (7.7) |

| Thyroiditis | 3 (2.6) | 5 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (6.8) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 0 | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 9 (7.7) |

| GBS | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 6 (5.1) |

| Facial paralysis | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Myelitis transverse | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Polyneuropathy | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Radiculopathy | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 5 (4.3) |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.4) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| Drug-induced liver injury | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) |

| Aplastic anemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Eye disorders | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Blepharitis | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Infections and infestations | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Meningitis aseptic | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Myositis | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Generalized dermatitis exfoliative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Lichenoid keratosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| AESI,∗ n (%) . | N = 117 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 . | Grade 2 . | Grade 3 . | Grade 4 . | Grade 5 . | Total . | |

| Patients with any AESI | 6 (5.1) | 17 (14.5) | 9 (7.7) | 6 (5.1) | 1 (0.9) | 39 (33.3) |

| Endocrine disorders | 8 (6.8) | 16 (13.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 (20.5) |

| Hypothyroidism | 6 (5.1) | 8 (6.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (12.0) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 (7.7) |

| Thyroiditis | 3 (2.6) | 5 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (6.8) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 0 | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 9 (7.7) |

| GBS | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 6 (5.1) |

| Facial paralysis | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Myelitis transverse | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Polyneuropathy | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Radiculopathy | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 5 (4.3) |

| Pneumonitis | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.4) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| Drug-induced liver injury | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) |

| Aplastic anemia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.7) |

| Eye disorders | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Blepharitis | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Infections and infestations | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Meningitis aseptic | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Myositis | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Generalized dermatitis exfoliative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Lichenoid keratosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

AE, adverse event; AESI, adverse events of special interest; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

AEs coded using MedDRA version 22.0.

Of 117 patients in the safety population, GBS- or polyradiculopathy-type events were reported in 8 (6.8%) patients (supplemental Table 8). These patients had no common demographic characteristics or medical antecedents, although 3 patients had an immune-related AE (irAE) affecting the thyroid gland before GBS/polyradiculopathy. The onset of GBS/polyradiculopathy was most common after 2 cycles of treatment, although in some patients it occurred after 6 or 7 cycles. Initial symptoms in patients were nonspecific, at times delaying intervention, and in 7 of 8 patients the first symptom was pain, including painful paresthesia, radicular pain, abdominal pain, and headache. Sensory symptoms (including paresthesia) and weakness were also common. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was reported in 5 patients and generally showed elevated white blood cell counts as well as elevated protein levels. Antiganglioside panel results were reported as positive in 1 patient. Electromyoneurography was positive for signs consistent with GBS/polyradiculopathy in 6 patients; abnormal magnetic resonance imaging results (gadolinium enhancement of the cauda equina and/or lumbosacral plexus) were reported in 4 patients. All 8 patients who experienced GBS discontinued study therapy. They all received IV immunoglobulins; 5 patients received plasma exchange; 6 patients received steroids; and 1 patient was administered rituximab. Of 8 patients, 5 had reported resolution of GBS before study closure.

Additional irAEs of interest included 1 patient who developed grade 4 type 1 diabetes mellitus after 2 cycles of Cami treatment; 1 patient who experienced grade 3 autoimmune hemolytic anemia after 12 cycles of Cami; and 2 patients who developed tubulointerstitial nephritis, both confirmed by kidney biopsy.

Exploratory biomarker analyses

In patients with valid biomarker data, no statistically significant differences in tumor cell CD25 H-score were observed between responders and nonresponders (P = .54; supplemental Figure 1); however, baseline sCD25 levels were statistically significantly higher in nonresponders than responders (P = .0037; supplemental Figure 2A). From baseline to cycle 3, day 1 pre-Cami infusion (end of cycle 2), there was a significantly greater decrease in sCD25 in nonresponders compared with responders (P = .025; supplemental Figure 2B); this trend was already visible at cycle 2, day 1 pre-Cami infusion (end of cycle 1), but it was not statistically significant (data not shown). There was no statistically significant difference in baseline CCL17 levels between responders and nonresponders (P = .22; supplemental Figure 3A), but from baseline to cycle 2, day 1 pre-Cami infusion (end of cycle 1), there was a statistically significant decrease in CCL17 in responders compared with nonresponders (P = .0031; supplemental Figure 3B); although this trend remained at cycle 3, day 1 pre-Cami (end of cycle 2), it was not statistically significant (data not shown).

ROC analyses were performed to assess the ability to predict response to Cami of baseline sCD25 alone or as part of models incorporating CD25 IHC, baseline CCL17, and pharmacodynamic changes of sCD25 and CCL17 observed at the end of cycle 1 and cycle 2. Baseline sCD25 alone or in combination with CD25 IHC or CCL17 baseline values had a modest predictive value for response to Cami treatment (supplemental Table 8). Slightly better predictive values were obtained by adding the changes from baseline of sCD25 and CCL17 to these models; however, the predictive level reached was still not satisfactory (supplemental Table 8; supplemental Figure 4).

PROs

The patient-reported outcomes (PRO) population included 116 patients. PRO results are described in detail in the supplemental Results. The mean change from baseline in European Quality-of-Life 5-Dimension 5-Level visual analog scale score and mean scores on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, lymphoma-specific subscale generally improved with treatment (supplemental Figure 5A-B).

Discussion

With novel agents advancing into earlier treatment lines, there is an increasing number of patients exposed to both BV and checkpoint inhibitors, yet for patients who relapse after or who have disease refractory to these treatments, there are limited treatment options.8-11 In this study, Cami demonstrated efficacy in a highly pretreated population, with >60% of patients in the posttransplant setting, including, in some cases, allogeneic stem cell transplant. The exploratory biomarker analyses conducted did not identify predictive biomarker(s) or models allowing for the early identification of patients more likely to respond to Cami with satisfactory sensitivity and specificity. Generally, patients reported a trend in improvement regarding overall health and lymphoma-related symptoms throughout the study. However, most patients (62.9%) were at least somewhat bothered by the side effects of treatment, reflective of the burden of Cami-related toxicities. Because of the single-arm design of this study, there is no comparison for Cami-related impact on PROs, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from the PRO data collected during the trial.

Use of Cami in this heavily pretreated population was associated with a high rate of AEs, with almost all (94.9%) patients reporting ≥1 TEAE considered related to Cami, and most patient experienced ≥1 grade ≥3 TEAE; however, toxicities were generally manageable with monitoring and dose modifications. The observed safety profile can be viewed as a combination of PBD-associated AEs (abnormal liver tests, cytopenias), anti-CD25–associated AEs (likely GBS or polyradiculopathy), and possibly toxicities that are caused by both components (likely skin toxicities). Skin toxicities represent the most common challenge for Cami delivery; skin and subcutaneous disorders were the most common TEAEs that led to dose modifications. They were often triggered by sun exposure and generally occurred within the first 2 cycles of treatment.

GBS- and polyradiculopathy-type events are a major concern for patients treated with Cami. Neurologic irAEs have also been reported with immune checkpoint inhibitors at a rate of 1% to 12% for any grade of neurologic irAEs and a rate of <1% for grades 3 to 4.19-22 With Cami, GBS/polyradiculopathy was seen at a rate of 6.8% in this study, which is consistent with the previous phase 1 study (5/77 [6.5%] patients with cHL).12 Of note, almost all cases of GBS/polyradiculopathy in patients treated with Cami were in patients with cHL, suggesting it may be disease associated. Cases of GBS occurring in patients with cHL have been previously reported in the literature.23-25 Recent studies suggest a role of CD25+ T-suppressor cells in GBS pathogenesis.26 Although the pathogenesis of GBS/polyradiculopathy events in patients treated with Cami remains unclear, it is plausible that reduction in the T-regulatory cell population triggers an immune-related polyneuropathy in susceptible patients with cHL. A case of GBS was reported in a patient treated with ipilimumab, an anti–CTLA-4 agent.27 The presentation of GBS and/or polyradiculopathy events in this study showed substantial interpatient variability, with no clear clinical correlate, which challenges the prospect of proactive identification of patients who could be at risk for developing GBS/polyradiculopathy after treatment with Cami. Other irAEs were observed in this study, including type 1 diabetes, tubulointerstitial nephritis, and a fatal event of aplastic anemia.

Other AESIs of particular note included tubulointerstitial nephritis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. In 2 of 4 patients who experienced these AESIs, the events developed after cycle 2 of Cami. All events were considered at least probably related to Cami and led to permanent discontinuation of treatment. These immune-related AEs were likely due to CD25 (ie, also expressed on regulatory T cells) targeting of Cami and reflect tolerability challenges with Cami that affect its clinical application.

In conclusion, Cami was efficacious in a heavily pretreated population of patients with R/R cHL, highlighting the value of targeting CD25. Objective responses to Cami were observed in most patients; although, a limitation of the ADCT-301-201 study was the single-arm design. However, the efficacy of Cami was overshadowed by the substantial issues in its safety profile. Cami is no longer being pursued at any dose or in combination treatment at this time.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Austin Horton of Citrus Health Group, Inc. (Chicago, Illinois), which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (2022) guidelines and funded by ADC Therapeutics SA.

This study was supported by ADC Therapeutics. Medical writing support was provided by Austin Horton, PhD, of Citrus Health Group, Inc. (Chicago, IL), which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines and funded by ADC Therapeutics SA. William Townsend acknowledges funding and research support from the UCLH Biomedical Research Centre.

Authorship

Contribution: A.F.H., S.M.A., P.L.Z., J.R., K.M., A.P., G.P.C., V.B., N.L.B., I.B.-B., M.H., J.K., J.M., K.J.S., R.H.A., P.F.C., R.-O.C., T.F., B.H., M.B.-O., S.I., Á.S., W.T., M.A., and C.C.-S. were principal investigators with the following contributions of provision of patient care, data analysis, and interpretation, development and revision of the manuscript, and provision of final approval of the submitted content; J.D., K.H., M.T., S.P., H.G.C., L.W., Y.N., M.L., and J.W. contributed with statistical analyses, data analysis and interpretation, development and critical revision of the manuscript, and provision of final approval of the submitted content; and all authors have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, including its accuracy and integrity.

Conflict of interest disclosure: A.F.H. received research support from AstraZeneca, ADC Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Seattle Genetics; and served as a consultant for AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, Adicet Bio, Allogene Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Genentech, Genmab, Karyopharm, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Regeneron, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, and Tubulis. S.M.A. received research support (paid to institution) from ADC Therapeutics, Affimed, AstraZeneca, BMS, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Takeda. P.L.Z. served as consultant for EUSA Pharma, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD), Sanofi, and Verastem; participated in advisory committees for ADC Therapeutics and Sandoz; and participated in speaker bureaus/advisory committees for BMS, Celltrion, EUSA Pharma, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, MSD, Roche, Servier, Takeda, TG Therapeutics, and Verastem. J.R. served as consultant/advisor for ADC Therapeutics, BMS, Kite Pharma, Novartis, and Takeda; served as speaker for ADC Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, and Takeda; owns stock in ADC Therapeutics and AstraZeneca (spouse); provided expert testimony for and received honoraria from ADC Therapeutics and Takeda; and received research funding from Takeda. K.M. served as a consultant for AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Genmab, Genentech, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, and Lilly. A.P. received honoraria from BeiGene, BMS, Eli Lilly, Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, and Merck Sharp and Dohme; served as a consultant for Hoffmann-La Roche AG; and is a current holder of stock options in Autolus Therapeutics and IGM Biosciences. G.P.C. received honoraria for speaker or advisory work from AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, BeiGene, Kite, Roche, SecuraBio, Sobi, and Takeda; and received research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, and Pfizer. V.B. received research support from BMS, Citius, Gamida Cell, and Incyte; served on an advisory board for ADC Therapeutics, Allogene, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, CRISPR, and Takeda; and served on a data safety monitoring board for Miltenyi Biotec. N.L.B. served on advisory boards for AbbVie/Genmab, Kite Pharma, Pfizer/Seagen, and Roche/Genentech; and received research funding from ADC Therapeutics, Autolus, BMS/Celgene, Forty Seven/Gilead, Genmab, Gilead/Kite Pharma, Janssen, Millennium, Pharmacyclics, Roche/Genentech, and Seattle Genetics. M.H. served as consultant for ADC Therapeutics, AlloVir, Autolus, BMS, Byondis, Caribou, CRISPR, Forte Biosciences, Genmab, Kite, and Omeros; participated in speaker bureaus for ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Kite; and received research support from ADC Therapeutics, Astellas Pharma, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. J.K. served on advisory boards for AbbVie, BeiGene, BMS, Genmab, Gilead, Ipsen, and Seagen; served as a consultant for AbbVie; and received research support from Merck Sharp and Dohme and Verastem. J.M. received research support (personally and to institution) from ADC Therapeutics. K.J.S. served as a consultant for Seagen; received honoraria from AbbVie, BMS, and Seagen; received research funding from BMS; served on a data safety monitoring for Regeneron; and received trial funding (paid to institution) from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Seagen, and Viracta. R.H.A. received honoraria or consultation fees from ADC Therapeutics, Autolus, BeiGene, Genentech, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Roche; and received research funding from BeiGene, Daiichi Sankyo Inc, Genmab, Genentech, Gilead, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron, Roche, and Seagen. P.F.C. served as consultant/advisor for ADC Therapeutics, BMS/Celgene, Genentech, Genmab, Novartis, Recordati Rare Disease, Synthekine, and Takeda. R.-O.C. served as a consultant/advisor for AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, BMS, Gilead, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche, and Takeda; received honoraria from BMS, Gilead, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Roche, and Takeda; received research funding from Gilead and Roche; and received travel grants from Amgen and Roche. T.F. served as a consultant for ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Epizyme, Genmab, Gilead Sciences, and Seagen; participated in speakers bureau for AbbVie, Genmab, and Seagen; received honoraria from AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BMS, Epizyme, Genmab, Gilead Sciences, Kymera, and Seagen; has equity ownership in Genomic Testing Cooperative and OMI; and received research funding from ADC Therapeutics, Alexion, AstraZeneca, BMS, Corvus, Daiichi, Genmab, Kymera, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Portola, Seagen, Tessa, and Trillium. B.H. served as consultant for ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, and BMS; and participated in a speaker bureau for BMS. M.B.-O. received honoraria from AbbVie, BMS, Incyte, Janssen, Kite Pharma, Roche, and Takeda; and received research funding from AbbVie, Incyte, Instituto Carlos III, Kite Pharma, and Roche. S.I. served on advisory boards and/or received honoraria from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Kite/Gilead, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Takeda. Á.S. served as consultant/advisor for Takeda, Novartis, Roche, and Janssen. W.T. has received honoraria and speaker fees from, and served on advisory boards for, ADC Therapeutics, Sobi, Roche, Incyte, Takeda, Janssen, and AbbVie; and has received research funding (to the institution) and travel reimbursement from Roche. M.A. served on advisory boards for BMS, Gilead, Incyte, Sobi, and Takeda; received research grants from Johnson & Johnson, Roche, and Takeda; and received travel grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Celgene, Gilead, Roche, and Takeda. J.D. is an external employee of ADC Therapeutics. K.H. is an employee of ADC Therapeutics with equity and stock options in the company. M.T. is an employee of ADC Therapeutics with equity and stock options in the company. S.P., at the time the work was conducted, was an employee of ADC Therapeutics and is an employee of Adcendo ApS; reports that an immediate family member is employed by Novartis; and holds equity/stock options in ADC Therapeutics, Alcon, Merck, Organon & Co, Novartis, and Sandoz. H.G.C. and Y.N. were employees of ADC Therapeutics at the time of the study and have equity and stock options in the company. L.W. is an employee of ADC Therapeutics with equity and stock options in the company. M.L. and J.W. were employees of ADC Therapeutics at the time of the study and have equity in the company. C.C.-S. reports consulting/advisory fees, research funding, and honoraria from ADC Therapeutics and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; reports additional consulting/advisory fees and honoraria from AbbVie, BMS/Celgene, Genmab, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Gilead, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Scenic Biotech, Sobi, and Takeda; reports honoraria from AstraZeneca and Incyte; and received travel, accommodation, and expenses support from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and Sobi. I.B.-B. declares no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.P. is Adcendo ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark. The current affiliation for H.G.C. is Debiopharm SA, Lausanne, Switzerland.

The current affiliation for Y.N. is Debiopharm SA, Lausanne, Switzerland.

M.L. has no current affiliation to report.

The current affiliation for J.W. is FoRx Therapeutics, Switzerland.

The current affiliation for Á.S. is Fejér County University Teaching Hospital, Székesfehérvár, Hungary.

Correspondence: Alex F. Herrera, City of Hope National Medical Center, City of Hope, 1500 E Duarte Rd, Duarte, CA 91010; email: aherrera@coh.org.

References

Author notes

Proposals requesting deidentified participant data collected for the study, after publication, can be sent to clinical.trials@adctherapeutics.com and will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.