Key Points

Patients with SCD in VOC are often under-triaged, resulting in poor adherence to pain management guidelines.

ESI is a major determinant of analgesic timing and appropriate ESI assignment of 2 reduces TTFA.

Visual Abstract

Guidelines from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute recommend assigning an Emergency Severity Index (ESI) acuity level 2 to patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) presenting to the emergency department (ED) with vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) and administering analgesia within 30 minutes of triage or 60 minutes of registration. The American Society of Hematology guidelines recommend analgesia within 60 minutes of ED arrival. In this study of adult patients with SCD presenting to the ED with uncomplicated VOC between 1 April and 30 September 2023, we compared time from triage to administration of first analgesia (TTFA), and time to second analgesia administration (TTSA) for those who were assigned ESI 2 vs 3. Sixty-six visits were included in the analysis. Median pain score at triage was 9 out of 10 (range, 6-10). ESI 2 was assigned to 23 visits (34.8%), and ESI 3 to 43 (65.2%). Four patients who were assigned ESI 3, left the ED without receiving analgesia. For the remaining 62 patients, median TTFA was 65 minutes for those assigned ESI 2, and 178 minutes for those assigned ESI 3 (P < .001), whereas median TTSA did not differ (72 vs 78 minutes; P = .485). In a Cox regression analysis including age, gender, SCD genotype, pain score at presentation, and ESI acuity level, only ESI correlated with TTFA (hazard ratio, 5.731; P < .001). System-based interventions to ensure assignment of ESI 2 can improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines regarding prompt analgesia for patients with SCD presenting to an ED for VOC.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive hereditary hemoglobinopathy affecting over 100 000 people in the United States and millions worldwide, with a disproportionate impact on those of African ancestry.1,2 Hemolytic anemia, vaso-occlusive events, and progressive end-organ damage characterize this condition. Vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) is a hallmark complication that results from sickled erythrocytes blocking small vessels and obstructing blood flow. Lysis of sickled cells releases reactive oxygen species resulting in a proinflammatory state. Manifestations of VOC include severe, acute pain that can occur in any part of the body, but most frequently involves the lower back and legs.3 Pain is the primary reason for emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations related to SCD. It leads to a direct annual health care cost of $1.1 billion in the United States alone, and is a significant predictor of early mortality and poor quality of life in patients living with SCD.4,5

Prompt assessment and administration of analgesia are essential for effective management of acute pain related to SCD.4,6 The Emergency Severity Index (ESI) allows patients to be categorized based on their acuity and resource requirements, with patients with lower scores requiring faster assessment and medical care.7,8 Appropriate ESI assignment for patients with SCD and VOC allows for rapid assessment and treatment initiation, and results in reduced ED stay, lower hospitalization rates, and increased patient satisfaction.6 The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines (2014) recommend assigning an ESI of 2 to patients with SCD presenting to an ED with VOC, and administering the first dose of analgesic within 30 minutes from triage or 60 minutes from registration.9 The American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines (2020) recommend analgesic administration within 60 minutes of ED arrival, as well as reassessment of pain and readministration of opioids every 30 to 60 minutes, as needed.4

Adherence to guidelines regarding ED management of patients with SCD presenting with VOC is known to be suboptimal. Wait times for patients with SCD have been shown to exceed those of other patients with similar pain scores by 25%.10 Adherence to the recommended ESI assignment remains inadequate, with studies showing appropriate ESI assignment ranging from 10% to 27% for patients with SCD presenting with VOC.11-14 Adherence to analgesic timing recommendations is also inadequate, with prior studies showing that only 5% to 48% of patients receive analgesia within the recommended time frame.13,14

Earlier assessment of a patient with SCD VOC in the ED may result in shorter door-to-administration time for first analgesia. The objective of our study was to evaluate the difference in time from triage to administration of first analgesia (TTFA) for patients with SCD presenting to the ED with VOC who were assigned ESI 2 compared with those assigned ESI 3.

Methods

We retrospectively examined the impact of ESI designation on TTFA in patients aged ≥22 years presenting to the adult ED with a SCD VOC between 1 April 2023 and 30 September 2023. The study was conducted in a quaternary care hospital in an urban city center that sees 60 000 ED visits annually, including ∼300 visits by patients with SCD. Guidelines for the care of patients with VOC have been in place since 2016. These guidelines are implemented regardless of the ESI category.

A total of 125 visits were identified through International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 code D57.3 (sickle cell disorders), and 66 were included in the analysis. Visits for VOC complicated by other diagnoses for which an assignment of ESI 2 was warranted regardless of the presence of VOC, and visits for other acute SCD diagnoses, including acute chest syndrome, were excluded. The primary outcome was TTFA, and the secondary outcome was the time between first and second analgesic administration (TTSA). Demographic data, pain score at triage, ESI assignment, and disposition were collected. TTFA and TTSA were compared between ESI groups using an independent t test. A time-to-event analysis utilizing a Cox regression model evaluated the occurrence and TTFA based on age, gender, sickle cell genotype, pain level at presentation, and ESI. A linear regression model was used to analyze TTSA.

Age was included from the chart review. Pain scores reported by the patient at presentation and ESI were included as assigned by the triage nurse. TTFA was measured as the difference in time between triage and administration of the first parenteral opioid analgesic, as recorded in the patient’s medication administration record in the electronic medical record Epic (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). TTSA was measured using the difference in time between the administration of the first and second parenteral opioid analgesic. Disposition was classified as discharge from the ED or hospital admission, as recorded in the patient’s chart. Patients who were placed in observation status were included as a hospital admission. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local institutional review board.

Results

Sixty-six ED visits by 41 unique patients met eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. Fifty-eight percent of patients were female, with a median age of 31 years (range, 22-77). Frequencies of SCD genotypes in the study population were Hemoglobin SS 63.4%, Hemoglobin SC 17.1%, Hemoglobin S-β0 thalassemia 4.9%, and Hemoglobin S-β+ thalassemia 14.6%. Median pain score at triage was 9 out of 10 (range, 6-10). ESI 2 was assigned to 23 visits (34.8%), and ESI 3 was assigned to 43 visits (65.2%). There was no significant difference in gender, age group, SCD genotype, or pain score at triage between those assigned an ESI of 2 or 3 (Table 1).

Description of the study population

| Description of the study population . | ESI 2, n = 23 . | ESI 3, n = 43 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 31 (22-77) | 31 (22-74) | .788 |

| Gender, % | .12 | ||

| Male | 52.2 | 32.6 | |

| Female | 47.8 | 67.4 | |

| SCD Genotype, % | .339 | ||

| HbSS | 69.6 | 62.8 | |

| HbSC | 4.3 | 16.3 | |

| HbS-β0 thalassemia | 4.3 | 9.3 | |

| HbS-β+ thalassemia | 21.7 | 11.6 | |

| Pain score at triage, median (range) | 9 (6-10) | 9 (6-10) | .567 |

| Description of the study population . | ESI 2, n = 23 . | ESI 3, n = 43 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 31 (22-77) | 31 (22-74) | .788 |

| Gender, % | .12 | ||

| Male | 52.2 | 32.6 | |

| Female | 47.8 | 67.4 | |

| SCD Genotype, % | .339 | ||

| HbSS | 69.6 | 62.8 | |

| HbSC | 4.3 | 16.3 | |

| HbS-β0 thalassemia | 4.3 | 9.3 | |

| HbS-β+ thalassemia | 21.7 | 11.6 | |

| Pain score at triage, median (range) | 9 (6-10) | 9 (6-10) | .567 |

HbSS, Hemoglobin SS; HbSC, Hemoglobin SC; HbS, Hemoglobin S.

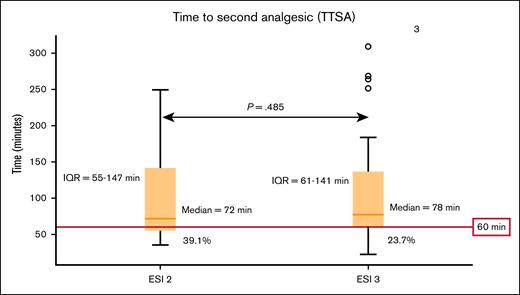

Analgesia was administered during 62 visits (93.9%). Analgesia was administered as an IV opioid formulation in all visits. The median TTFA was 65 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 56-103) for the ESI 2 group, and 178 minutes (IQR, 98-445) for the ESI 3 group (P < .001; Figure 1). In contrast, median TTSA did not differ between the ESI 2 and 3 groups (72 minutes [IQR, 55-147] vs 78 minutes [IQR, 61-141]; P = .485; Figure 2). Four patients who were assigned ESI 3, left without receiving analgesia after a median of 349 minutes.

Box plot showing the median TTFA and 25th to 75th IQR for ESI groups 2 and 3 with NHLBI first analgesic recommendation cutoff highlighted in red. Median TTFA was 65 minutes for ESI 2, and 178 minutes for ESI 3 (P < .001). IQR for TTFA in patients assigned an ESI of 2 was 56 to 103 minutes, whereas the IQR for patients assigned an ESI of 3 was 98 to 445 minutes. The 30-minute cutoff for TTFA from triage as recommended by NHLBI is highlighted in red. None of the patients had TTFA within the recommended cutoff.

Box plot showing the median TTFA and 25th to 75th IQR for ESI groups 2 and 3 with NHLBI first analgesic recommendation cutoff highlighted in red. Median TTFA was 65 minutes for ESI 2, and 178 minutes for ESI 3 (P < .001). IQR for TTFA in patients assigned an ESI of 2 was 56 to 103 minutes, whereas the IQR for patients assigned an ESI of 3 was 98 to 445 minutes. The 30-minute cutoff for TTFA from triage as recommended by NHLBI is highlighted in red. None of the patients had TTFA within the recommended cutoff.

Box plot showing the median TTSA and 25th to 75th IQR for ESI groups 2 and 3 with ASH subsequent analgesic recommendation cutoff highlighted in red. Median TTSA was 72 minutes for ESI 2, and 78 minutes for ESI 3 (P = .486). IQR for TTSA in patients assigned an ESI of 2 was 55 to 147 minutes, whereas the IQR for patients who were assigned an ESI of 3 was 61 to 141 minutes. The 60-minute cutoff for TTSA as recommended by ASH is highlighted in red. Second analgesic administration within the recommended cutoff occurred in 39.1% and 23.7% of those assigned an ESI of 2 and 3, respectively.

Box plot showing the median TTSA and 25th to 75th IQR for ESI groups 2 and 3 with ASH subsequent analgesic recommendation cutoff highlighted in red. Median TTSA was 72 minutes for ESI 2, and 78 minutes for ESI 3 (P = .486). IQR for TTSA in patients assigned an ESI of 2 was 55 to 147 minutes, whereas the IQR for patients who were assigned an ESI of 3 was 61 to 141 minutes. The 60-minute cutoff for TTSA as recommended by ASH is highlighted in red. Second analgesic administration within the recommended cutoff occurred in 39.1% and 23.7% of those assigned an ESI of 2 and 3, respectively.

In a Cox regression analysis of TTFA based on age, gender, SCD genotype, pain score at presentation, and ESI, ESI was the only significant factor correlating with TTFA (hazard ratio, 5.731; P < .001; Figure 3). The linear regression model for TTSA based on age, gender, sickle cell genotype, pain at presentation, and ESI failed to reach significance (P = .073).

Graph showing the results of the Cox regression analysis of TTFA as above with grouping based on ESI assignment. ESI was the only significant factor correlating with TTFA (HR, 5.731; P < .001). HR, hazard ratio.

Graph showing the results of the Cox regression analysis of TTFA as above with grouping based on ESI assignment. ESI was the only significant factor correlating with TTFA (HR, 5.731; P < .001). HR, hazard ratio.

Twenty-five patients (40.9%) were admitted to the hospital, with an admission rate of 39.1% for ESI 2%, and 41.8% for ESI 3 (P = .521). TTFA and TTSA did not significantly impact hospital admission, with P values of .251 and .907, respectively.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that ESI assignment is a major determinant of TTFA, highlighting its important role in adherence to evidence-based guidelines for rapid administration of analgesia in the management of SCD VOC.

In our study, ESI 2 was assigned to 23 visits (34.8%), and ESI 3 to 43 (65.2%). The observed trend of more patients assigned an ESI score of 3 rather than 2 is consistent with prior studies. In studies by Almuqamam et al11 and Froke et al,13 86.9% and 78.7% of patients with SCD and uncomplicated VOC presentations were assigned an ESI of ≥3, respectively. These findings suggest a consistent pattern of under-triaging patients presenting with SCD VOC, and failure to adhere to NHLBI guidelines regarding recommended ESI assignment.

In a Cox regression analysis based on age, gender, sickle cell genotype, pain score at presentation, and ESI, only ESI correlated with TTFA. In this analysis, an ESI of 3 as compared with 2 was associated with a hazard ratio of 5.731, indicating that patients assigned an ESI of 2 were 5.731 times more likely to receive their first analgesic earlier, compared with those assigned an ESI of 3. Although factors such as gender and pain score at presentation were found to impact analgesic timing significantly in previous studies,11,12 similar results were not noted in our study, highlighting the critical role appropriate triaging plays in expediting care for patients with SCD VOC.

Utilization of time-to-event in analyzing TTFA allowed the inclusion of patients who departed before receiving care, a population often omitted in prior studies. The 4 patients in our study who departed without receipt of analgesia likely had delays in care due to an assignment of ESI 3 rather than 2.

Median TTFA from triage was 65 minutes for patients assigned an ESI 2, and 178 minutes for ESI 3, representing delays of 35 and 148 minutes beyond the NHLBI’s recommended analgesic timing from triage, respectively. Adherence to this recommendation might be difficult considering ED overcrowding.6 However, there is room for improvement in reducing the duration of delay. Similar limitations in adherence to TTFA guidelines were noted in prior studies.11-14

Median TTSA was 72 and 78 minutes in patients assigned an ESI of 2 and 3, respectively. Delay in pain reassessment and opioid redosing is usually due to resource limitations. Efforts such as individualized care plans and access to a day hospital can result in more effective pain relief in the acute setting.6,15 Unlike the TTFA, the TTSA did not show a significant difference between the groups assigned ESI 2 or 3. This suggests that the key factor causing the difference between the groups is the patient’s movement from the waiting room to a patient care area, where clinicians can assess and treat patients. Once this transition occurs, we found no association between ESI category and the timing of an additional dose of analgesic. It should be noted that the time between doses did not meet the ASH guideline of 30 to 60 minutes in 39.1% and 23.7% of those assigned an ESI of 2 and 3, respectively (P = .2).

Patients with SCD often identify the care received in the ED as the aspect of their management with the greatest need for improvement.16 Beyond delays in analgesic administration, systemic issues within the ED contribute to disparities in the management of this patient population. Prior studies show that individuals with SCD usually perceive ED care as suboptimal, citing inadequate pain management, provider bias, and long wait times as significant concerns.6,16 Smith et al reported that despite experiencing pain on 54.5% of the studied days, patients with SCD pursued medical care only 3.5% of the time, indicating a hesitancy to utilize EDs for the management of pain when home treatment fails.17 This reluctance may stem from prior negative encounters emphasizing the need for standardized treatment protocols, improvements in patient-provider relationships, and enhanced resource allocation. Availability of additional options, such as infusion centers, is another important approach to improving care for patients with SCD.15

The study by Linton et al18 serves as an essential comparison point when evaluating system-based interventions for SCD VOC. In their study, nurses were randomly assigned to receive prompts encouraging ESI 2 triage assignment. Although the intervention improved proper ESI assignment within the group (64.95% vs 35.05%), it failed to achieve a statistically significant difference between groups with regard to time to first analgesia (P = .06). Accurate comparison of these results with our study population is limited by the lack of stratification based on ESI assignment, and the difference in the TTFA between our study population and the control group in Linton et al (178 vs 115 minutes).18 Additionally, while we cannot know the specifics of their hospital, our EDs regularly operate at overcapacity, which maximizes the impact of ESI categorization.

These results suggest that one size does not necessarily fit all, and interventions should be tailored to the specific areas of delay within the institute. Identifying areas of delay and their contributing factors is essential to optimizing the care of patients with SCD. Whether by addressing triage practices or improving difficulties and delays from provider assessment to delivery of appropriate analgesia by implementing individualized care plans. These factors provide opportunities for continuous quality improvement tailored to optimize the care of patients with SCD within the institute.19,20

Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced a measure under consideration whereby hospitals will be asked to report the mean time to administration of analgesics for patients with SCD VOC.21 This focus by the largest payer of medical care in the United States further highlights the urgency of addressing these disparities. The adoption of quality measures incentivizing timely pain management for VOC supports system-based interventions aimed at improving adherence to evidence-based guidelines. Our study underscores the need for standardization of triage practices, advocating for the consistent assignment of an ESI of 2 to patients presenting with VOC.

Ultimately, our findings highlight the importance of structured, system-based approaches to improving the timeliness and quality of care for patients with SCD. By prioritizing accurate triage assignments, refining pain management protocols, and addressing educational gaps, clinicians may be able to improve outcomes for patients with SCD through better adherence to established guidelines.

Limitations of our study are inherent to the retrospective single-center design. Access to care in our overcrowded urban ED may not be representative of other EDs across the country. In addition, the relatively small sample size may limit the ability to detect significant associations. The short time frame of the study may limit the detection of seasonal variation in ED volume, which could impact results. Furthermore, our study examined a process measure rather than a discrete clinical outcome, although improvement in time to first analgesia could increase patient satisfaction. Subsequent research is needed to establish these patient-centered outcomes. We defined TTFA as the interval from triage to first analgesia, rather than from arrival to first analgesia as recommended by ASH guidelines. This approach allowed us to specifically evaluate the impact of ESI categorization on analgesic timing, as the interval from arrival to triage occurs independently of ESI. However, our definition may underestimate overall delays in analgesia, as it does not account for time from arrival to triage, which can contribute to treatment delays. Finally, ascertainment of improvement in pain following the first analgesic, the necessity of subsequent doses, and the exact timing of departure from the ED is limited by documentation in the chart.

In conclusion, prompt pain control in accordance with guidelines is the cornerstone for the management of VOC, which is the leading cause of ED visits and admissions for patients with SCD. Our study demonstrates an association between ESI triage level at initial presentation with TTFA for patients with SCD presenting with VOC. System-based intervention to ensure an appropriate assignment of ESI 2 may result in significantly improved quality of care provided to patients with SCD presenting with VOC.

Authorship

Contributions: A.A.H., B.S., R.G.W., and J.Y.L. conceived of and designed the study; A.A.H. and D.P. extracted the data and performed chart reviews, with supervision from R.G.W. and J.Y.L.; A.A.H. and D.P. conducted the statistical analysis, with supervision from R.G.W. and J.Y.L.; A.A.H. and D.P. drafted the manuscript; O.C., B.S., M.R.B., R.G.W., and J.Y.L. critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved of the final version; R.G.W. and J.Y.L. supervised the study; and A.A.H. takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.G.W. received research funding from Becton, Dickinson, and Company, Roche Diagnostics, Global Blood Therapeutics, Inc, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Egetis Therapeutics AB, EndPoint Health, Inc, CSL Behring, and Pfizer Inc; received research funding from CoapTech, LLC through an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant (R44DK115325); received research support in the form of equipment and supplies from Cepheid and Eldon Biologicals A/S; and is a paid consultant for the National Foundation of Emergency Medicine. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Abdulaziz Abu Haimed, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine 110 South Paca St, Baltimore, MD 21201; email: Abuhaimed.aziz@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Presented in abstract form at the 66th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 8 December 2024.

Data are available on request to the corresponding author, Abdulaziz Abu Haimed (abuhaimed.aziz@gmail.com).