TO THE EDITOR:

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a severe, genetic hemoglobinopathy that predominantly affects Black populations in the United States and leads to many complications, including stroke, acute pain, and acute chest syndrome.1 Fortunately, improved management in recent years has led to increases in life expectancy for those with SCD in the United States, with most individuals now surviving into adulthood.2 Thus, it has become increasingly important to assess if this progress has also resulted in these individuals achieving life goals commonly reported among adults, such as family-building.3

Studies of adolescents and young adults with SCD demonstrate that 61% to 76% desire future biological parenthood.4,5 Although SCD and its treatments have multiple reproductive health implications,6,7 parenthood rates among adult men with SCD have not been described. For instance, several studies show that many men with SCD have abnormal semen parameters,6,8,9 but it remains unclear if and how these parameters relate to actual biological parenthood rates. Additionally, the potential for SCD genetic transmission10 and increasing SCD severity in adulthood11 raise the potential that men with SCD may not pursue biological parenthood at the same rate as their unaffected peers. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to describe biological parenthood rates among a large sample of adult men with SCD in the United States. We also aimed to compare the biological parenthood rates of Black men with SCD from an age-standardized registry sample to a representative sample of Black men in the United States.

This was cross-sectional analysis of Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC)12 registry and National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) data.13 The recruitment strategy and data collection methods for the SCDIC can be found in previous publications.12,14 Deidentified SCDIC data (eg, demographics and Pregnancy and Conception survey results) from males enrolled on the registry between 2017 to 2019 were obtained by a request through the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center.15 Males aged 15 to 45 years who completed the “Have you ever fathered a baby?” question on the Pregnancy and Conception survey were included. Because the Pregnancy and Conception survey prompts males to respond based on pregnancies where they have been the father, responses to this question were used to determine biological parenthood rates among men with SCD.

The NSFG is a population-based survey administered by the National Centers for Health Statistics.12 The NSFG uses a complex survey design to sample households within rotating geographic regions, then conducts face-to-face interviews with eligible respondents in sampled households. When weighted, it is representative of the noninstitutionalized population of men and women aged 15 to 45 years in the United States. These interviews include reporting demographic data and answering a series of questions about biological children with all sexual partners, such as “Have you and [NAME OF PARTNER] ever had a child together?” Answers to these questions are used to determine biological parenthood rates. NSFG data on Black men aged 15 to 45 years from 2017 to 2019 were used for this analysis because it most closely matched the ages, race, and years that data were collected from the SCDIC participants.

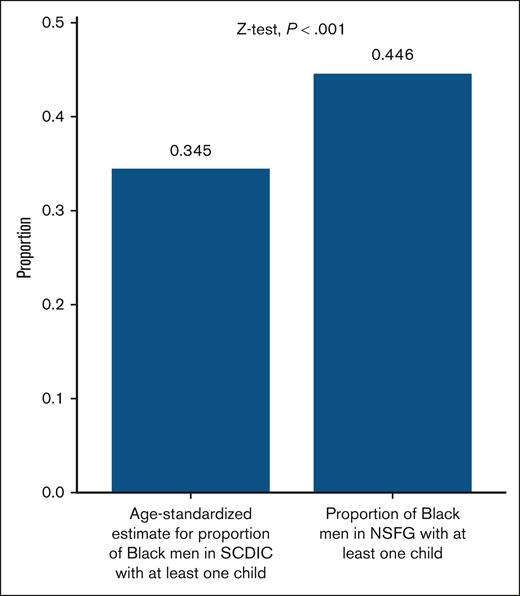

Descriptive statistics summarized the parenthood rates. Because the proportions of men in each age category differed between the SCDIC and NSFG data sets, prior to comparing parenthood rates using a 1 proportion Z test, age-standardized estimates of biological fatherhood were calculated for the SCDIC cohort using the NSFG age distribution (ie, the US population age distribution) as a standard. The overlap age-standardized proportion was calculated by multiplying the proportion of men who were biological fathers in each age group by the proportion of men in this age group in the standard population.16P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. R statistical software was used for analysis (version 4.3.2).

Of the males with SCD enrolled in the SCDIC registry between 2017 to 2019, 1024 were included (Table 1). Of these, 313 (30.6%) reported ever fathering a baby. Biological parenthood rates significantly differed between the SCDIC and NSFG cohorts (Figure 1).

Demographics of included men in the SCDIC and NSFG cohorts

| Characteristic . | Overall SCDIC Cohort, n = 1024 . | Black NSFG Cohort, n = 1026, unweighted∗ . | Black SCDIC Cohort, % (SE) . | Black NSFG Cohort % (SE), weighted∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.6 | -— | — | — |

| 15-24 | 401 | 384 | 39.5 (1.6) | 33.7 (2.6) |

| 25-29 | 230 | 194 | 22.6 (1.4) | 18.4 (1.8) |

| 30-34 | 173 | 169 | 17.2 (1.2) | 16.4 (1.9) |

| 35-39 | 112 | 139 | 10.3 (1.0) | 16.6 (1.8) |

| 40-45 | 107 | 140 | 10.3 (1.0) | 15.0 (1.6) |

| Missing | 1 | — | 0.1 (0.1) | — |

| Race | ||||

| Black/African American | 946 | 1026 | 100 | 100 |

| Other | 51 | — | — | — |

| White | 2 | — | — | — |

| Missing | 25 | — | — | — |

| Household income per year | ||||

| ≤$25 000 | 450 | 315 | 44.2 (1.6) | 26.9 (2.1) |

| $25 001-$50 000 | 206 | 355 | 20.2 (1.3) | 31.1 (1.8) |

| $50 001-$75 000 | 114 | 193 | 11.4 (1.0) | 23.1 (2.6) |

| $75 001-$100 000 | 53 | 62 | 5.4 (0.7) | 6.0 (1.1) |

| >$100 000 | 56 | 101 | 5.7 (0.8) | 12.9 (1.6) |

| Missing | 145 | — | 13.1 (1.1) | — |

| Education level | ||||

| No high school diploma or GED | 199 | 276 | 19.6 (1.3) | 23.2 (2.1) |

| High school diploma or GED | 331 | 393 | 32.5 (1.5) | 36.4 (2.3) |

| Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 304 | 233 | 29.3 (1.5) | 26.3 (2.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 169 | 124 | 16.8 (1.2) | 14.1 (1.7) |

| Missing | 21 | — | 1.9 (0.4) | — |

| Employment status | ||||

| Working now | 345 | 706 | 34.1 (1.5) | 73.1 (1.9) |

| Student | 198 | 127 | 19.5 (1.3) | 11.8 (1.6) |

| Not working† | 458 | 193 | 44.3 (1.6) | 15.1 (1.9) |

| Missing | 23 | — | 2.1 (0.5) | — |

| Characteristic . | Overall SCDIC Cohort, n = 1024 . | Black NSFG Cohort, n = 1026, unweighted∗ . | Black SCDIC Cohort, % (SE) . | Black NSFG Cohort % (SE), weighted∗ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.6 | -— | — | — |

| 15-24 | 401 | 384 | 39.5 (1.6) | 33.7 (2.6) |

| 25-29 | 230 | 194 | 22.6 (1.4) | 18.4 (1.8) |

| 30-34 | 173 | 169 | 17.2 (1.2) | 16.4 (1.9) |

| 35-39 | 112 | 139 | 10.3 (1.0) | 16.6 (1.8) |

| 40-45 | 107 | 140 | 10.3 (1.0) | 15.0 (1.6) |

| Missing | 1 | — | 0.1 (0.1) | — |

| Race | ||||

| Black/African American | 946 | 1026 | 100 | 100 |

| Other | 51 | — | — | — |

| White | 2 | — | — | — |

| Missing | 25 | — | — | — |

| Household income per year | ||||

| ≤$25 000 | 450 | 315 | 44.2 (1.6) | 26.9 (2.1) |

| $25 001-$50 000 | 206 | 355 | 20.2 (1.3) | 31.1 (1.8) |

| $50 001-$75 000 | 114 | 193 | 11.4 (1.0) | 23.1 (2.6) |

| $75 001-$100 000 | 53 | 62 | 5.4 (0.7) | 6.0 (1.1) |

| >$100 000 | 56 | 101 | 5.7 (0.8) | 12.9 (1.6) |

| Missing | 145 | — | 13.1 (1.1) | — |

| Education level | ||||

| No high school diploma or GED | 199 | 276 | 19.6 (1.3) | 23.2 (2.1) |

| High school diploma or GED | 331 | 393 | 32.5 (1.5) | 36.4 (2.3) |

| Some college, no bachelor’s degree | 304 | 233 | 29.3 (1.5) | 26.3 (2.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 169 | 124 | 16.8 (1.2) | 14.1 (1.7) |

| Missing | 21 | — | 1.9 (0.4) | — |

| Employment status | ||||

| Working now | 345 | 706 | 34.1 (1.5) | 73.1 (1.9) |

| Student | 198 | 127 | 19.5 (1.3) | 11.8 (1.6) |

| Not working† | 458 | 193 | 44.3 (1.6) | 15.1 (1.9) |

| Missing | 23 | — | 2.1 (0.5) | — |

GED, General Educational Development; SD, standard deviation.

Unweighted numbers are from the men surveyed as part of NSFG, whereas weighted percentages were calculated from the unweighted NSFG data so that they are representative of the noninstitutionalized population of Black men aged 15 to 45 years in the United States between 2017 to 2019.

Includes disabled, temporarily laid off, unemployed, stay-at-home parents, and those on sick/paternity leave.

Although prior studies suggest that most adolescents and adults with SCD desire biological parenthood,4,5,17 we found that less than a third of men with SCD aged 15 to 45 years were biological parents. We also found that ∼25% fewer Black men with SCD were biological parents compared to similarly aged Black men in the United States overall. These findings are notable because a recent publication, also from the SCDIC registry, found that only 17% of men with SCD reported infertility.18 Although differences in the infertility and parenthood rates from men in the SCDIC registry may be due to unassessed attempts to conceive in the infertility study,18,19 lower parenthood rates could also be related to several other factors that have been studied in similar populations. For instance, research in adult male childhood cancer survivors suggests that their reduced parenthood rates are related to impaired fertility from cancer treatment,20 financial burdens from cancer treatment,21 and concerns about genetic transmission of cancer.22 Similar to adult childhood cancer survivors, adult males with SCD have a severe illness that started in childhood that may also put them at risk for infertility.6,7 They also experience financial burdens from their costly disease23 and fears of passing on SCD to their children.10 Financial concerns may be contributing to reduced parenthood among men with SCD, especially given that 45% of the SCDIC cohort were not working at the time of the survey. It is also possible that overall health (physical and mental) and social isolation may influence romantic relationships24 and ultimately parenthood rates. Emerging literature has highlighted gaps in reproductive health counseling among adolescents and young adults with SCD and their desire for more fertility-related information.4,17 Therefore, our findings support the need for future studies to identify if these and/or other factors are contributing to reduced biological parenthood among men with SCD to inform evidence-based guidelines.

Our study has a few limitations. First, the questions used to determine biologic parenthood among the two cohorts were not identical. Also, although the SCDIC registry reflects a diverse population of men with SCD, it may not reflect men with SCD who are not engaged in care. The SCDIC registry only samples participants from large, academic medical centers, and therefore, may not reflect the management and/or parenthood rates of all men living with SCD. The NSFG also has some limitations. It does not include men who are institutionalized, and undercounts men’s total number of children, largely due to underreporting of children fathered by young men and children born outside of marriage.25 Although fatherhood (whether a man has any children) is more accurately reported in the NSFG than the number of children, these estimates still represent a lower bound of the proportion of men who are fathers in the United States.

In conclusion, despite improvements in survival, our findings suggest that having SCD may still hinder achievement of life goals, such as parenthood. Future studies are needed to elucidate the factors that influence this so that targeted interventions and guidelines can be developed to ensure that these men also achieve their reproductive and family-building goals.

IRB approval was obtained through a Human-Subjects Research Determination because the data from both sources was deidentified and publicly available. This research was labeled as not-human subjects research.

Contribution: A.N.Y. cleaned and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; S.R.H. refined the methodology for the weighted estimates for analysis and wrote the manuscript; S.S.C. and S.C. performed data analysis; T.P.K., A.K., and R.M.C. wrote the manuscript; B.L.K. refined methodology and wrote the manuscript; L.B. performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript; and L.N. and S.E.C. designed the research, oversaw the project, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Susan E. Creary, Abigail Wexner Research Institute, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 700 Children’s Dr, NEOB 3rd Floor, Columbus, OH 43205; email: susan.creary@nationwidechildrens.org.

References

Author notes

L.L. and S.E.C. are joint senior authors.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Susan E. Creary (susan.creary@nationwidechildrens.org).