Key Points

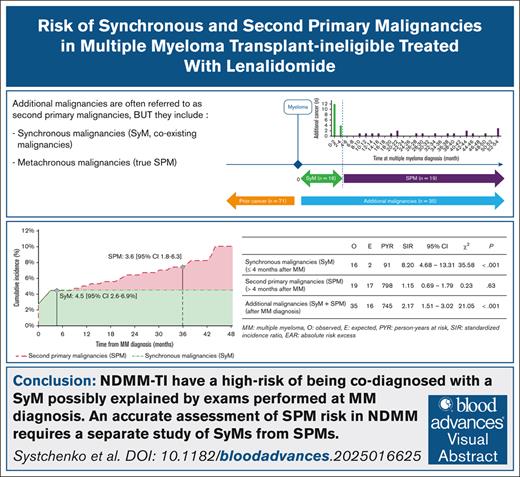

Patients with MM have a high risk of SyM codiagnosis, possibly explained by examinations performed at the time of MM diagnosis.

The risk of SPM related to Len, without differentiating between SyM and SPM, was likely overestimated.

Visual Abstract

An increased risk of second primary malignancies (SPMs) was reported for transplant-ineligible (TI) patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) exposed to lenalidomide (Len), with the caveats that Len was often coexposed to alkylating agents and the studies did not exclude synchronous malignancies (SyMs). We aimed to evaluate the respective SyM over SPM risks in TI patients with NDMM treated with Len as frontline therapy. We conducted a high-resolution, population-based cancer registry study, which allowed completeness of the primary end point (SyMs and SPMs) without reporting bias, and provided a cohort more representative of real-life than those in clinical trials. The inclusion period started recently (2018) due to the reimbursement of Len in France. Additional malignancies (AdMs) diagnosed ≤4 months of MM diagnosis were defined as SyMs; those diagnosed >4 months were considered SPMs. The person-year approach was used with an indirect standardization. With a median follow-up of 36 months, 360 consecutive TI patients with NDMM were identified, including 174 treated with Len. In total, 35 patients (9.7%) had an AdM (standardized incidence ratio [SIR], 2.17), 16 (4.4%) had an SyM (SIR, 8.20), and 19 (6.4%) had an SPM (SIR, 1.15). Among patients treated with Len, 12 (6.9%) had an SPM (SIR, 1.28), and cumulative incidence was 3.6% at 3 years. TI patients with NDMM have a high risk of being codiagnosed with an SyM possibly explained by examinations performed at the time of MM diagnosis. In contrast, patients treated with Len who were never exposed to conventional chemotherapy did not seem to have an increased risk of SPM compared with the general population.

Introduction

The increased life expectancy of transplant-ineligible (TI) patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) has led to renewed concerns about long-term risks, especially for additional malignancies (AdMs) often called second primary malignancies (SPMs).1 The occurrence of AdMs for patients with MM raises questions about the relationship across these multiple primary malignancies.2 Although various causes may be proposed, MM (including premalignant stages) and age (with a median MM diagnosis of ∼70 years)–related immunodeficiencies are considered major risk factors.1 The exact role of the treatments given for the first cancer onto the development of the subsequent AdMs is absolutely key to determine for all cancer drugs under clinical development, because it is key to determine whether the drug is suspected to be either an initial event or fostering a preexisting malignant stage.

AdMs include SyMs (coexisting malignancies, either inactive/incidental or active/symptomatic) and metachronous malignancies (true SPMs). SyMs are considered as an additional cancer diagnosed within 4 to 6 months of the first cancer, whereas SPMs are diagnosed after 4 to 6 months.3 There are reasons to exclude SyMs from the analysis of the SPM risk in general, particularly when the objective is to determine the relationship to cancer drugs. First, providing a causal relationship between the treatment of a given cancer and an SyM diagnosis is questionable due to the short duration of exposure to the treatment. Second, at the time of MM diagnosis, whole-body imagery and systematic marrow examinations are performed.4 This high diagnostic pressure could lead to the detection of incidental cancers (not yet symptomatic/inactive cancers), thus leading to a certain overdiagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, the distribution of SyM and SPM is unknown in MM, including the respective risks and the impact on treatment of MM alongside treatment of the AdMs.

Lenalidomide (Len), the first-in-class immunomodulating agent, remains a major treatment development in MM.5-9 An increased risk of developing SPMs was reported for patients with NDMM exposed to Len,10 including in TI patients with NDMM, supporting the conclusion that the increased risk of SPMs was correlated to Len exposure in MM. We believe this meta-analysis had some limitations: the patients exposed to Len were often treated in combination with alkylating agents; the risk ratio was compared to the non-Len group instead of the general population; and the SyM were not excluded from SPM. We hypothesized that the excess risk of SPM related to Len reported in this meta-analysis might rather be an excess risk of AdMs, a sum of SyMs and SPMs.

We sought to evaluate the SyM risk in TI patients with NDMM and to dissect it from the assessment of the SPM risk, in patients treated with Len in the absence of any exposure to alkylating agents.

Methods

Study design

This high-resolution population-based study included all patients with NDMM in the Poitou-Charentes area (Western France, 1.8 million inhabitants) between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2020, exhaustively collected in the Poitou-Charentes General Cancer Registry. Cases were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology third edition.11 The inclusion period started in 2018 because reimbursement of Len for TI patients with NDMM was approved in France in 2017 (Transparency Committee, CT-15763). A medical source file review was systematically performed in all centers to provide supplementary data, especially for characteristics and treatment of MM.

The Poitou-Charentes General Cancer Registry

The registry uses a multisource information system that gather data from cytopathology laboratories, the medical information departments of public and private hospitals, regional cancer networks, health insurance organization departments, and general and specialist practitioners. It is, by definition, multicentric and exhaustively captures all health care–related data from all patients with MM in the Poitou-Charentes area. The registry is certified by the French National Registries Evaluation Committee and approved by the French Data Protection Authority (National Commission for Data Protection and Liberties authorization number 907303). Our study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and all applicable regulatory requirements, including the 2008 version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were informed of their data registration and given the right to deny access or to rectify their personal data.

Definition of exposure to lenalidomide

Patients were treated with Len as frontline setting for ≥2 cycles per months, either alone or in combination with proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib) and/or anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab or isatuximab). Patients with NDMM were excluded if they had concomitant exposure to chemotherapy, either cyclophosphamide, anthracyclines, or melphalan. Patients aged <70 years were excluded because high-dose melphalan therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation is the recommended treatment for these patients in France.4

Case definition

In our study, we classified cancer events diagnosed in patients with MM as a prior cancer when diagnosed before MM. AdM was defined when diagnosed at the same time or after MM diagnosis (discovered during the workup of MM). AdM is a second primary cancer independent of any first cancer (MM or prior cancer), neither an extension, nor a recurrence, nor a metastasis.2

AdMs diagnosed ≤4 months of MM diagnosis were labeled SyMs, and those diagnosed after 4 months were classified as SPMs. The definition of the synchronicity period was defined by recommendations of the French Network of Cancer Registries (FRANCIM).3 Nonmelanoma skin cancers were analyzed independently of other invasive cancers due to different recording methods (nonindividual verification, completeness not guaranteed).

Analysis of cancer incidence

The person-year approach was used with an indirect standardization. Standardized incidence ratio (SIR) was defined as: the number of cancers observed (O)/expected number of cancers (E) if patients presented the same cancer risk than the Poitou-Charentes population of the same age and sex.12 E was the calculated as product of the number person-years at risk and the benchmark cancer incidence rate by age, sex, and year of diagnosis in Poitou-Charentes. SIRs for SyMs were analyzed in the first 4 months of follow-up and were calculated only for the NDMM-TI population (because SyM cannot be attributed to MM treatment). SIRs for SPMs were analyzed only for patients with follow-up >4 months (after the synchronous period, thereby excluding patients with early deaths or SyMs). The reported risk of SyMs or SPMs are compared with those of the general population of the same age and sex.

Statistical analyses

The 95% confidence interval (CI) and the SIR significance tests were calculated using the Breslow and Day method for expected AdM staffing levels >10, and the Samuels method for staffing <10.12,13 Only the first AdM of each patient were selected for the overall risk estimate. For the probability of AdM occurrence, the Fine and Gray regression model was used, considering competing events.14 Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from MM diagnosis until death from any cause. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between 2018 and 2020, 360 TI patients with NDMM were diagnosed. The patient and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The male-to-female gender ratio was 1.3 (205/155, self-reported gender), and the median age at diagnosis of MM was 80 years (range, 70-103). One hundred seventy-four patients were treated with Len according to the study design: 43 patients (25%) received monotherapy, and 131 patients (75%) received combination therapy. The distribution of patients treated with Len was as follows: Rd (Len, dexamethasone) for patients with frailty (25%), D(±V)Rd (daratumumab ± bortezomib Rd) for patients in therapeutic trials or last included (18%), and VRd for others (57%). The median duration of Len treatment was 23 months (range, 1-56).

Patient characteristics

| . | TI patients with NDMM (N = 360) . | TI patients with NDMM treated with Len∗ (n = 174) . | With SyM (n = 16) . | With SPM (n = 12) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (min-max), y | ||||

| At diagnosis of MM | 80 (70-103) | 78 (70-92) | 80 (72-89) | 74 (70-85) |

| At diagnosis of AdM | 80 (72-89) | 78 (72-87) | ||

| Gender ratio† (male-to-female) | 1.3 (205/155) | 1.2 (94/80) | 3 (12/4) | 1.4 (7/5) |

| Personal history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous cancer | 71 (20) | 30 (17) | 4 (25) | 1 (8) |

| Previous radiotherapy | 31 (9) | 16 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| Previous chemotherapy | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Subtypes of myeloma | ||||

| Smoldering MM | 66 (18) | 2 (1) | 4 (25) | |

| Active MM | 291 (81) | 172 (99) | 12 (75) | 12 (100) |

| Plasmacytoma | 3 (1) | |||

| ISS‡ | ||||

| I | 47 (16) | 36 (21) | 1 (8) | 5 (41) |

| II | 80 (28) | 54 (31) | 3 (25) | 2 (17) |

| III | 91 (31) | 49 (29) | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| Unknown | 73 (25) | 33 (19) | 4 (33) | 2 (17) |

| Treatment combinations | ||||

| No treatment | 61 (17) | 0 | 4 (25) | 0 |

| With chemotherapy | 52 (14) | 0 | 3 (19) | 0 |

| Without Len | 68 (19) | 0 | 6 (38) | 0 |

| Len alone ± dex | 45 (13) | 43 (25) | 2 (12) | 2 (17) |

| Len with anti-CD38 | 22 (6) | 22 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Len with PI | 102 (28) | 99 (57) | 1 (6) | 10 (83) |

| Len + anti-CD38 + PI | 10 (3) | 10 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| . | TI patients with NDMM (N = 360) . | TI patients with NDMM treated with Len∗ (n = 174) . | With SyM (n = 16) . | With SPM (n = 12) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (min-max), y | ||||

| At diagnosis of MM | 80 (70-103) | 78 (70-92) | 80 (72-89) | 74 (70-85) |

| At diagnosis of AdM | 80 (72-89) | 78 (72-87) | ||

| Gender ratio† (male-to-female) | 1.3 (205/155) | 1.2 (94/80) | 3 (12/4) | 1.4 (7/5) |

| Personal history, n (%) | ||||

| Previous cancer | 71 (20) | 30 (17) | 4 (25) | 1 (8) |

| Previous radiotherapy | 31 (9) | 16 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| Previous chemotherapy | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Subtypes of myeloma | ||||

| Smoldering MM | 66 (18) | 2 (1) | 4 (25) | |

| Active MM | 291 (81) | 172 (99) | 12 (75) | 12 (100) |

| Plasmacytoma | 3 (1) | |||

| ISS‡ | ||||

| I | 47 (16) | 36 (21) | 1 (8) | 5 (41) |

| II | 80 (28) | 54 (31) | 3 (25) | 2 (17) |

| III | 91 (31) | 49 (29) | 4 (33) | 3 (25) |

| Unknown | 73 (25) | 33 (19) | 4 (33) | 2 (17) |

| Treatment combinations | ||||

| No treatment | 61 (17) | 0 | 4 (25) | 0 |

| With chemotherapy | 52 (14) | 0 | 3 (19) | 0 |

| Without Len | 68 (19) | 0 | 6 (38) | 0 |

| Len alone ± dex | 45 (13) | 43 (25) | 2 (12) | 2 (17) |

| Len with anti-CD38 | 22 (6) | 22 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Len with PI | 102 (28) | 99 (57) | 1 (6) | 10 (83) |

| Len + anti-CD38 + PI | 10 (3) | 10 (6) | 0 | 0 |

dex, dexamethasone; ISS, International Staging System; max, maximum; min, minimum; PI, proteasome inhibitors.

Only with a follow-up of >4 months.

Gender was self-reported by patients.

Only for active MM.

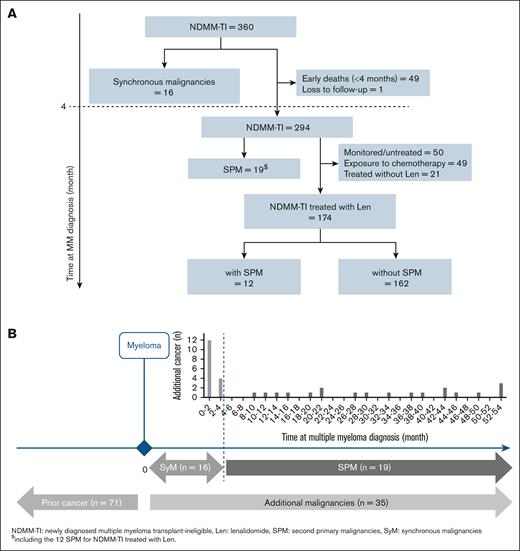

With a median follow-up of 42 months (95% CI, 40-44), 71 of 360 patients (20%) had a cancer diagnosed before MM diagnosis, and 35 of 360 patients (9.7%) were diagnosed with AdM after MM diagnosis, including 16 SyMs and 19 SPMs (Figure 1A). The types of AdMs are summarized in Table 2.

Flow chart and distribution of additional malignancies. (A) Flow chart. (B) Multiple primary cancers in TI patients with NDMM (n = 360). With a median follow-up of 42 months (95% CI, 40-44), 35 of 360 (9.7%) patients had a diagnosis of AdMs after MM diagnosis, including 16 SyMs and 19 SPMs. Of the 174 patients treated up front with Len-based regimens, 12 (6.9%) had an SPM.

Flow chart and distribution of additional malignancies. (A) Flow chart. (B) Multiple primary cancers in TI patients with NDMM (n = 360). With a median follow-up of 42 months (95% CI, 40-44), 35 of 360 (9.7%) patients had a diagnosis of AdMs after MM diagnosis, including 16 SyMs and 19 SPMs. Of the 174 patients treated up front with Len-based regimens, 12 (6.9%) had an SPM.

Types of AdMs

| . | AdMs (n = 35) . | SyM (n = 16) . | SPM in TI patients with NDMM (n = 19) . | SPM in patients treated with Len (n = 12) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic malignancies, n (%) | 9 (26) | 8 (50) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 3 | 3 | ||

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | 3 | 3 | ||

| Lymphoid blood diseases | 2 | 2 | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Solid malignancies, n (%) | 26 (74) | 8 (50) | 18 (95) | 11 (92) |

| Colorectal | 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Prostate | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Breast | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lung | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Bladder | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Kidney | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Head and neck | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Liver and bile duct | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Pseudomyxoma peritonei | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| . | AdMs (n = 35) . | SyM (n = 16) . | SPM in TI patients with NDMM (n = 19) . | SPM in patients treated with Len (n = 12) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic malignancies, n (%) | 9 (26) | 8 (50) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 3 | 3 | ||

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | 3 | 3 | ||

| Lymphoid blood diseases | 2 | 2 | ||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Solid malignancies, n (%) | 26 (74) | 8 (50) | 18 (95) | 11 (92) |

| Colorectal | 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Prostate | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Breast | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lung | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Bladder | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Kidney | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Head and neck | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Liver and bile duct | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Pseudomyxoma peritonei | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Sixteen TI patients with NDMM had SyMs, representing 4.4% (16/360) and 46% (16/35) in the whole population and among AdMs, respectively; half of which were hematologic malignancies, and the other half were solid malignancies. Ten of these SyMs (63%) were inactive/incidental malignancies.

After the synchronicity period (beyond 4 months), 294 of 360 patients with MM were analyzable for SPM risk (excluding 16 SyMs, 49 early deaths, and 1 patient lost to follow-up; Figure 1B). Nineteen patients had a diagnosis of SPM, 6.4% (19/294) and 54% (19/35) in the whole population and among AdMs, respectively (Table 2). The median age at diagnosis of SPM was 78 years (range, 72-87).

Incidence risk of AdM in the overall TI patients with NDMM

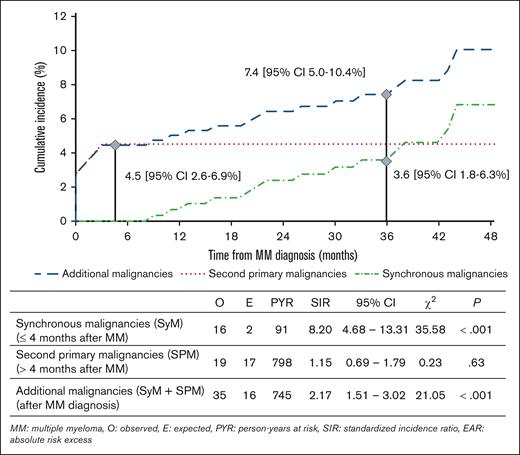

The risk of AdMs (SyMs + SPMs) was significantly increased by 117% (SIR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.51-3.02; P < .001) compared to the general population. The cumulative incidence of AdMs was 7.4% at 3 years (95% CI, 5.0-10.4). Results in the overall TI population with NDMM are summarized in Figure 2.

Risk of AdMs in TI patients with NDMM (n = 360). The risk of AdMs (SyMs + SPMs) was increased (SIR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.51-3.02) compared to the general population. When we dissected the risk from SPMs to SyMs, we observed a significant excess risk of SyMs (SIR, 8.20; 95% CI, 4.68-13.31) but not of SPMs (SIR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.69-1.79).

Risk of AdMs in TI patients with NDMM (n = 360). The risk of AdMs (SyMs + SPMs) was increased (SIR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.51-3.02) compared to the general population. When we dissected the risk from SPMs to SyMs, we observed a significant excess risk of SyMs (SIR, 8.20; 95% CI, 4.68-13.31) but not of SPMs (SIR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.69-1.79).

With 16 SyMs observed for 2 expected, the risk of SyMs was significantly increased by 720% (SIR, 8.20; 95% CI, 4.68-13.31; P < .001) in TI patients with NDMM compared to the general population. The cumulative incidence of AdMs was 4.5% at 4 months (95% CI, 2.6-6.9).

In comparison, the risk of SPMs was increased by 15% (SIR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.69-1.79; P = .63). The cumulative incidence of SPM was 3.6% at 3 years (95% CI, 1.8-6.3).

Incidence risk of SPM in patients treated with Len

Among the 174 patients treated up front with Len-based regimens, 12 (6.9%) had a diagnosis of SPM, including 1 hematologic malignancy and 11 solid malignancies (Table 2). The median times from MM diagnosis and initiation of Len to occurrence of an SPM were 35 months (range, 8-52) and 27 months (range, 8-47), respectively.

The cumulative incidence of SPM was 3.6% at 3 years (95% CI, 1.5-7.2). With 12 SPMs observed for 9 expected, the risk of SPM was increased by 28% (SIR, 1.28; 95% CI, 0.66-2.23; P = .49) in TI patients with NDMM treated with Len-based regimens, compared to the general population. There were no significant differences in SPM risk incidence rates by gender, age, prior cancer, and duration of Len exposure. In univariate analysis, and considering the occurrence of death as a competitive event, no predictive factor was significantly associated with the SPM occurrence: sex (P = .66), age (P = .41), prior cancer (P = .48), and duration of Len (P = .05).

Sixteen (9.2%) patients treated with Len up front developed nonmelanoma skin cancer, and the cumulative incidence at 3 years was 3.2% (95% CI, 0.4-6.0). The cumulative incidence at 3 years for all metachronous cancers (SPM + nonmelanoma skin cancers) was 7.5 (95% CI, 3.4-11.6).

Outcome of TI patients with NDMM

Overall, 49 patients (14%) of 360 TI patients with NDMM died within 4 months of myeloma diagnosis, including 9 of 16 patients with an SyM diagnosis. The causes of death for patients with SyM were: SyM (n = 3), myeloma (n = 3), other causes (n = 2), and unknown (n = 1). The median OS was 28 months (95% CI, 24-71) for patients with SyM and 42 months (95% CI, 43-54) for patients without SyM (P = .81). The cumulative incidence at 3 years was 3.6% (95% CI, 1.8-6.3) for SPM, 16.5% (95% CI, 12.8-20.7) for death due to MM, and 26.4% (95% CI, 21.8-31.2) for death due to other causes.

Among the 174 TI patients with NDMM treated with Len, 66 (38%) died, including 5 of 12 patients with SPM. The cumulative incidence of death was 37% at 3 years. Causes of death for patients without SPM were myeloma (n = 25 [41%]), other causes (n = 16 [24%]), and unknown (n = 20 [33%]). Causes of death for patients with SPM were SPM (n = 4), another cause (n = 1), and none attributed to myeloma. The median OS was not reached for patients with SPM and was 57 months (95% CI, 24-59) for patients without SPM (P = .81).

Treatment strategies at time of AdM diagnosis

At the time of SyM diagnosis, 7 of 16 patients (44%) required a treatment for SyM (excluding 6 monitored and 3 palliative care), including 3 who had a modification of the SyM treatment. Eight patients (50%) required a concomitantly MM treatment (excluding 5 smoldering MM and 3 palliative care), including 3 of 8 who had a modification of the MM treatment. The 2 patients with an indication of radiotherapy (prostate cancer) or chemotherapy (lung cancer) did not receive the standard of care for SyM (limited to hormonotherapy and surgery, respectively) and for MM (Len was excluded from the MM treatment regimen). These 2 patients died of SyM. Treatment strategies at time of SyM are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

At time of SPM diagnosis, 5 (41%) of 12 patients had a modification of MM treatment: 4 had a temporary discontinuation of Len during the surgical procedure (of 7 operated patients), and 1 patient had a permanent interruption of Len because multidisciplinary meeting retained a relationship of SPM to Len. This last patient had a slow biological progressive disease for MM and was able to receive a treatment for metastatic kidney cancer (cabozantinib in frontline followed by nivolumab), and myeloma remained on watch-and-wait approach. One patient (8%) did not receive the standard of care for SPM: multidisciplinary meeting retained a contraindication to chemotherapy due to MM treatment, and the head and neck cancer was treated by radiotherapy alone.

Discussion

Our high-resolution population-based study is the first, to our knowledge, to report on the SyM compared to SPM in MM. We observed a significantly higher risk of SyM in TI patients with NDMM (SIR. 8.20), which could be explained by the examinations performed at MM diagnosis (whole-body imagery and bone marrow examination) that allow a large screening of the patients for the diagnosis of other types of cancers. We did not observe the increased risk of SPM related to Len in TI patients with NDMM reported in the recent studies. Our results raise the question of whether this risk remains in the absence of coexposure to melphalan and with a comparison with the general population.

To evaluate the risk of SPM in population-based cancer registries, and to differentiate it from SyM, French and Italian Cancer Registries recommend to exclude a period following the first cancer diagnosis (synchronicity period).3,15 Indeed, at the time of cancer diagnosis, many examinations are performed, and this high diagnostic pressure can lead to overdiagnosis of SyM, some of which are inactive/incidental malignancies. The definition of the synchronicity period is important, defined between 1 and 6 months in different studies, without clear epidemiological justification and considered as 4 months in France.3 We used this definition of 4 months according to French recommendations, but there is no validation specific to MM. In our study, 16 AdMs were diagnosed during the first 4 months (12 in first 2 months and 4 between 2 and 4 months) and none between 4 and 8 months. This supports the cutoff definition of 4 months in our study for MM, although it should be validated in a larger cohort.

The risk of SyM overdiagnosis has already been analyzed by other types of cancer with noteworthy differences, but never for MM. The excess risk of SyM for TI patients with NDMM in our study (SIR, 8.20) was higher than the excess risk of all other types of cancers reported (the highest being for head and neck, SIR of 3.31).3 This greater risk was probably explained by examinations performed at MM diagnosis (bone marrow cytology and whole-body computed tomography scan), examinations that can be considered as excellent individual cancer screening tests. The high proportion (two-thirds) of incidental cancers among SyMs supports the suspicion of overdiagnosis in the synchronicity period. This raises questions on whether the “individual cancer screening” of MM diagnosis influences the SPM risk. In other words, could this excess risk and the early identification of SyMs reduce the risk of SPM? Our median follow-up of 3 years was too short to answer this question and to determine whether SPM risk increases later (eg, after 5 years). An update of our data or other studies with longer follow-up would be of interest.

It is complicated to estimate the share of risk linked to myeloma. The hypothesis that MM itself might be a risk factor for the development of AdMs was hypothesized many years ago.16 Tumor-induced immunodeficiency, deregulated release of cytokines, chronic inflammation, and common tumor cell precursors can play a role in increasing the susceptibility of patients with MM to AdM development.1,17 To estimate myeloma-related increased SyM risk, we should have a nonmyeloma comparison population with the same screening examinations. This population does not exist, and this question therefore remains unanswered.

We did not report an increased risk of SPM in patients treated with Len, in contrast to several meta-analyses.10,18 As a reminder, these studies reported an excess risk of additional cancers, after MM diagnosis, in TI patients with NDMM treated with Len-based regimens, but including SyMs and SPMs. Furthermore, most patients in the Len group were exposed to chemotherapy, notably melphalan. Up-front coexposure to Len and oral melphalan seems the main driver of increased risk of second hematologic cancers (hazard ration [HR], 4.86; 95% CI, 2.79-8.46). In contrast, exposure to Len plus cyclophosphamide (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.30-5.38) or Len plus dexamethasone (HR, 0.86 95% CI, 0.33-2.24) did not increase this risk vs melphalan alone.18 Another study of a US cohort does not support an increased risk of additional cancers in patients with MM treated with Len outside the context of juxtaposed melphalan therapy.19 To our knowledge, our study was the first to compare the SPM risk in patients treated with Len with that of the general population, rather than with a to a non-Len group (from clinical trials or another cohort). Based on our study, TI patients with NDMM treated frontline with Len did not have an excess risk of SPM compared to a French population. These results are reassuring information for patients, even if they must be confirmed on a larger sample with a longer follow-up.

Concerning treatment strategies at time of SPM diagnosis, 4 of 7 operated patients had a temporary discontinuation of Len during the surgical procedure without impact on myeloma control (absence of relapse). Therefore, this temporary discontinuation seems safe, not mandatory, and can be proposed depending on cytopenias under Len or the type of surgery. It is encouraging to note that the vast majority of patients benefited from the standard of care of treatment for SPM (92%) and were not offered a palliative care approach, suggesting that medical oncologists seem to have integrated that treatment of TI patients with NDMM has greatly evolved these past years.20 For patients with SyM, 3 of 7 (43%) patients did not receive the standard of care for SyM, and 2 of 3 died of SyM consequently. For these patients, particular attention must be accorded with a collegial discussion between clinicians.

Our study had several strengths

First, all cancer cases were exported from a population-based general cancer registry, allowing completeness of AdMs (SyMs and SPMs), a possible bias in clinical trial data. Second, the systematic review of medical source files allowed to achieve a high-resolution population-based study, which purpose is to guarantee a cohort more representative of real-life than clinical trials. Third, we believe that our research methodology, excluding MM exposed with concomitant chemotherapy, excluding SyM and by comparison to the general population, was a more appropriate approach to evaluate the SPM risk for TI patients with NDMM treated frontline with Len-based regimens. To the best of our knowledge, this endeavor is of further importance as these Len-based regimens never exposed to conventional chemotherapy, notably alkylating agents, frame the future of the treatment for frontline TI patients with NDMM.

Our study also had several limitations

First, the average population size and limited follow-up (3 years) did not allow to calculate the SPM risk with greater power and precision. Longer follow-up is particularly important to assess the SPM risk in patients with prolonged survival. Second, our study was based on the population of Poitou-Charentes (1.8 million inhabitants). The validation of our results requires a larger cohort with longer follow-up.

In conclusion, TI patients with NDMM have a high risk of additional cancers, principally SyMs, mainly incidental discoveries, that could be explained by exams performed at MM diagnosis. Patients treated up front with Len-based regimens never exposed to conventional chemotherapy, notably alkylating agents, did not seem to have an increased risk of SPM compared with the general population. The validation of our results requires larger cohorts and importantly longer follow-up. We recommend that future studies pay a particular attention to separate SyMs from SPMs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the team of Poitou-Charentes General Cancer Registry, the Clinical Investigation Center of Poitiers University Hospital, the University of Poitiers, the Regional Health Agency of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, and all hospital centers that treated patients.

The Cancer Registry of Poitou-Charentes is funded by the Regional Health Agency of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, the Poitiers University Hospital, the University of Poitiers, the Institut National du Cancer, and Santé Publique France.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors conceived and designed the study, collected and assembled the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Systchenko, Poitou-Charentes General Cancer Registry, INSERM CIC 1402, CHU de Poitiers, 2 rue de la Milétrie, 86021 Poitiers Cedex, France; email: thomas.systchenko@chu-poitiers.fr.

References

Author notes

Data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Thomas Systchenko (thomas.systchenko@chu-poitiers.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.