Key Points

Activated human ILC2s limit GVHD and increase survival in xenograft models.

Interleukin 4 reduces ex-ILC2 generation during human ILC2 expansion.

Visual Abstract

Reconstitution of stem cells and enhancement of the barrier function of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is critical to the resolution of intestinal acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD). Previously, our group has shown in murine models that type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) generate proteins in the GI tract that enhanced GI tract barrier function, and diminished the expansion and function of proinflammatory donor cells when given to recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplant. Therefore, the infusion of donor ILC2s could treat or prevent GI tract aGVHD but, for this approach to be clinically applicable, robust expansion of a homogeneous population of human ILC2s is needed. Here, we describe a method for the rapid expansion of a uniform population of human ILC2s that decrease GVHD in NOD scid gamma mice. The addition of interleukin 4 to the culture was critical to prevent the expansion of proinflammatory ILC1-like cells. Our approach should allow for the evaluation of human ILC2 cells to treat therapy-resistant GI tract aGVHD.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) is the standard of care for the treatment of patients with relapsed or high-risk acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, relapsed/refractory lymphoid malignancies, and congenital or acquired bone marrow failure syndromes.1-3 Morbidity associated with allo-HSCT limits greater utilization of this therapy, with acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) a common complication in recipients of allo-HSCT.4,5 aGVHD is mediated by donor T cells that recognize minor or major histocompatibility complex disparities between the donor and host, and typically involves the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, liver, and skin.6-8 aGVHD of the GI tract that does not respond to corticosteroids or ruxolitinib has a poor prognosis, with <50% of patients surviving 18 months after diagnosis.9,10

The GI tract constantly replenishes surface epithelial cells, with new cells being generated by intestinal stem cells.11 Given that the GI tract can use these mechanisms to repair itself, it remains unclear why they are not sufficient to repair tissue damage mediated by aGVHD. Recent reports demonstrate that the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligand amphiregulin is critical for GI tract repair.12 In the GI tract, amphiregulin is produced by type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) and intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts.13-15 Our group and others have shown that ILC2 cells in the colon and small intestine are poorly regenerated after allo-HSCT, and that infusion of these cells in mouse models prevented and treated aGVHD.16 However, whether human ILC2 cells are effective in the prevention or treatment of aGVHD is not known.

One significant concern with the use of ILC2 cells therapeutically is the extremely limited number of these cells available in the bloodstream or in local tissues.13 As a result, expansion of ILC2s is critical for their therapeutic use. In this study, we describe a novel approach for the rapid expansion of human ILC2 cells, and demonstrate a critical role for blocking the conversion of ILC2 to ILC1-like cells in vitro to improve the therapeutic function of ILC2 cells to prevent GVHD in a humanized mouse model.

Methods

ILC2 cell isolation

For all experiments, nonmobilized peripheral blood (PB) leukapheresis products were purchased from Memorial Blood Center (St. Paul, MN). ILC2 cells were enriched by RosetteSep human ILC2 enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC), or EasySep human ILC2 enrichment kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC), or the combination of EasySep human natural killer (NK)-cell-negative selection kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC) and EasySep human CD56-positive selection II kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Where indicated, ILC2s were sorted on a BD FACSAria II following enrichment.

Cell culture and cytokines

ILC2 populations were cultured in either alfa minimum essential media (α-MEM; Corning Inc, Oneonta, NY) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini), or Iscove modified Dulbecco media (IMDM; Corning Inc) with 10% FBS, both with 1% penicillin/streptomycin with cytokine combinations as described in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Recombinant human interleukin 2 (IL-2; TECIN; Teceleukin) was provided by National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD), or purchased from PeproTech. Recombinant human IL-7 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), IL-4 (R&D), IL-17E (IL-25; R&D), IL-33 (Miltenyi Bio, Gaithersburg, MD), and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP; PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ) were purchased from the indicated vendors. For comparison to the Reid et al cultures system, IL-25 was excluded from that group. The OP9-DLL1 cell line has been described previously.17

Flow cytometry and antibodies

Single-cell suspensions were stained for 20 minutes on ice with the indicated antibodies, followed by incubation with a Fixable Viability Dye (Thermo Fisher). Human antibodies specific for the following targets were purchased from BioLegend: CD1a (HI149), CD11c (3.9), CD14 (HCD14), CD19 (HIB19), CD34 (581), CD45 (2D1), CD94 (DX22), CD123 (6H6), FceR1 (AER-37), T-cell receptor (TCR; IP26), TCR (B1), CD127 (A019D5), CD161 (HP-3G10), CD294/CRTH2 (BM16), IL-4 (MP4-25D2), IL-5 (JES1-39D10), IL-10 (JES3-19F1), and IL-13 (JES10-5A2). Human antibodies specific for CD56 (TULY56), CD303/BDCA2 (AC144), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ; B27) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), Miltenyi Biotec, or BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ), respectively. For intracellular staining, cells were stimulated for 4 hours with 1× Cell Stimulation Cocktail plus protein transport inhibitors (eBioscience), and stained using the BD Fixation/Permeabilization solution kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were collected using an LSRII or Fortessa cytometer (BD Biosciences), and analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar, now BD Biosciences).

RNA analysis

Paired-end FASTQ files were aligned via STAR (V.2.7.6a) to an Ensembl transcriptome on reference genome GRCh38; Salmon (V.1.4.0) was used to quantify gene counts. Quality of data was determined using FastQC (V.0.11.9) for FASTQ files, and Picard (V.2.22.4, CollectRnaSeqMetrics) for BAM files. Samtools’ (V.1.4.0) sort function was used to sort BAM files. Gene expression matrices were then imported into R (V.3.6.0), appended to Ercolano data, and mapped to HGNC symbols with biomaRt (V.2.40.5), before undergoing differential expression analysis using the DESeq2 (V.1.24.0) Bioconductor package. Gene signatures were calculated using Bioconductor’s singscore (V.1.4.0) simpleScore function.

Assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing analysis

Nf-core’s atacseq (V.1.2.2) pipeline (with parameters --genome GRCh38--narrow_peak, otherwise default), was run using Nextflow (V.20.01.0), which was utilized for this analysis. The pipeline measured the quality of paired-end FASTQ files using FastQC (V.0.11.9), and aligned them to reference genome GRCh38 using BWA (V.0.7.17). After the data were filtered (SAMtools V.1.10, BAMtools V.2.5.1, Pysam V.0.15.3) and quality metrics evaluated (Picard V.2.23.1, Preseq V.2.0.3), narrow peaks were called using MACS2 (V.2.2.7.1). Peaks were annotated using HOMER (V.4.11), and a consensus peak set was generated via BEDTools (V.2.29.2). Reads in consensus peaks were quantified using the featureCounts function of Bioconda’s subread (V.2.0.1) package before differential accessibility analysis was performed using DESeq2 (V1.26.0) in an R (V.3.6.3) environment. The resulting bigWig files were visualized with the consensus peaks bed file mapped to reference genome GRCh38 in IGV (V.2.15.1). The 2 day 0 samples’ bigWig data were averaged in the visualization.

Mice

NOD/scid/γc–/– (NSG) mice were purchased from the Animal Husbandry Core at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), and housed in specific-pathogen-free facilities at UNC-CH.

Xenograft transplant

Xenograft transplant was performed as previously described,18 with NSG mice receiving 200 cGy radiation 24 hours before transplant. Briefly, at transplant, NSG mice received 8.5 × 106 human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with or without 10 × 106 ILC2s IV via tail vein injection. Transplant recipients were monitored for weight loss and clinical signs of aGVHD 3 times per week using a semiquantitative scoring system, as previously described.19,20 For ILC2 migration experiments, IL-33 (PeproTech) was given (100 μg) 1 day prior to cell infusion.

ILC2 isolation from GVHD target organs after transplant

Human cells were recovered 4 days after transplant. Single-cell suspensions were established using Miltenyi Lung Dissociation kit (130-095-927) and Miltenyi Lamina Propria Dissociation kit (130-097-410) as per manufacturer’s instruction; liver and spleen cells were isolated by dissociation through 70-μm filters (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Red blood cells were osmotically lysed. Cells were evaluated by flow cytometry.

Serum cytokine evaluation

Serum was collected from NSG mice 28 days after transplant of PBMCs with or without ILC2. Quantification of human tumor necrosis factor (TNF) was performed using a human TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Invitrogen) as per manufacturer’s instruction. Optical density was calculated by reading absorbance on a Synergy 2 spectrophotometer (Biotek, Winooski, VT). Additional quantification of human TNF, IL-13, IFN-γ, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor was performed using Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 17-plex Assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA; catalog no. M500031YV) as per manufacturer’s instructions, and was analyzed using the Bio-Plex 200 system (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Statistical analysis

RNA and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC) sequencing were evaluated as described. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and evaluated by the Mantle-Cox log-rank test. Differences in body weight and clinical scores were evaluated by 2-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni corrections for repeated measures of multiple comparisons. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay data were evaluated using 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Analysis was generated using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA).

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UNC-CH.

Results

To assess the clinical feasibility of using human ILC2s to prevent GI tract aGVHD, we first determined if ILC2 cells could be enriched from PB cells and expanded ex vivo. To this end, we performed comprehensive analyses of ILC2 enrichment from healthy control donor apheresis units to determine the optimal cell culture conditions for ILC2 expansion. We performed ILC2 cell enrichment using either the RosetteSep, EasySep, or EasySep (EasySep NK+CD56) kits from STEMCELL Technologies (Vancouver, BC) and compared the purity and recovery rate of each approach. ILC2 cells were characterized by the absence of lineage markers (CD1a– Cd11c– CD14– CD19– CD34– CD94– CD123– FceR1– TCRαβ– TCRgd–) and expression of the cytokine receptor subunit IL-7Rα (CD127), the natural killer cell receptor CD161, and CRTH2/CD294 that is expressed on ILC2s, T helper 2 (Th2) cells, eosinophils, and basophils. Consistent with the frequency of ILC2 cells found in normal healthy humans,21 ILC2 cells were found to comprise 0.023% to 0.062% of total CD45+ cells in our apheresis units. Between the 3 enrichment methods tested, the EasySep ILC2 kit and EasySep NK+CD56 kits produced the greatest enrichment of ILC2 cells (8% and 5%, respectively). There was an increased number of cells recovered using the RosetteSep and EasySep ILC2 kits compared with the EasySep NK+CD56 kit (supplemental Figure 1A-B; Figure 1A-C). Following RosetteSep enrichment, the average yield of ILC2 cells from 109 PBMCs was 105 (Figure 1D).

A stable method to purify and recover human ILC2 cells ex vivo. Human ILC2 cells were enriched from the same apheresis unit cells using either the RosetteSep human ILC2 enrichment kit, EasySep human ILC2 enrichment kit, or a combination of EasySep human NK cell enrichment kit and EasySep human CD56 positive selection II kit. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. (A) Flow cytometric profiles of pre-enrichment and postenrichment samples divided by lineage markers (Lin) and CD127. (B) Lin–CD127+ gated populations divided by CD161 and CRTH2. (C) Graph showing the yield of ILC2 cells using the 3 different enrichment methods. Blood samples were from 3 donors split into test samples, 1 for each kit. Each symbol represents an individual donor; small horizontal lines indicate the group mean (± standard deviation). (D) A graph showing the absolute cell numbers of human ILC2 cells enriched from an apheresis unit of PB cells using RosetteSep human ILC2 enrichment kit, 6 different donors; small horizontal line indicates the mean (± standard deviation).

A stable method to purify and recover human ILC2 cells ex vivo. Human ILC2 cells were enriched from the same apheresis unit cells using either the RosetteSep human ILC2 enrichment kit, EasySep human ILC2 enrichment kit, or a combination of EasySep human NK cell enrichment kit and EasySep human CD56 positive selection II kit. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. (A) Flow cytometric profiles of pre-enrichment and postenrichment samples divided by lineage markers (Lin) and CD127. (B) Lin–CD127+ gated populations divided by CD161 and CRTH2. (C) Graph showing the yield of ILC2 cells using the 3 different enrichment methods. Blood samples were from 3 donors split into test samples, 1 for each kit. Each symbol represents an individual donor; small horizontal lines indicate the group mean (± standard deviation). (D) A graph showing the absolute cell numbers of human ILC2 cells enriched from an apheresis unit of PB cells using RosetteSep human ILC2 enrichment kit, 6 different donors; small horizontal line indicates the mean (± standard deviation).

Following the enrichment process, ILC2 cells were cultured in α-MEM media with 20% FBS, 20 IU/mL of recombinant human IL-2, and 50 ng/mL each of IL-25 and IL-33 for 10 days, with a subset of cultures continued for 21 days. After 10 days of culture with replenishment of media including cytokines every 3 days, 79% of the cells isolated using the RosetteSep kit produced IL-13 but not IFN-γ upon phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin stimulation. In contrast, 10% to 25% of cells enriched with the EasySep ILC2 or EasySep NK+CD56 kits, and cultured for 10 days produced IFN-γ, which is characteristic of ILC1-like cells (supplemental Figure 2A; Figure 2A). Thus, although the cell populations enriched by EasySep ILC2 kit and NK+CD56 kits include higher percentages of ILC2, a greater proportion of those cells preferentially acquire an IFN-γ–producing ILC1-like phenotype during expansion. In contrast, the frequency of ILC2 cells expressing IFN-γ was much lower using the RosetteSep kit. ILC2 cells enriched by the RosetteSep kit expanded 587-fold by day 10 of culture, which was significantly greater than the expansion of ILC2 cells using the EasySep ILC2 kit or EasySep NK+CD56 kits (Figure 2B).

Human ILC2 cells enriched via the RosetteSep ILC2 kit and expanded in α-MEM readily proliferate ex vivo. Enriched human ILC2 cells were cultured in α-MEM (A-B) or IMEM (C-D) media with 20% FBS, and supplemented with 20 IU/mL IL-2, 50 g/mL IL-25 and IL-33 for 10 days. While ILC2 cells are homogeneous by day 10 of expansion, for the subset of experiments where a greater number of cells was needed for downstream analyses, cultures were maintained for an additional 4 to 11 days (total 14-21 days). (A) Flow cytometric profiles of 10 days cultured human ILC2 cells. Cells were stimulated by cell stimulation cocktail with protein inhibitors followed by intracellular staining. (B) A graph showing cell numbers of IL-13-producing ILC2 cells after 10 days of culture. Numbers in red denote fold change of ILC2 cell expansion. (C) Flow cytometric profiles of 10 day cultured ILC2 cells. Cells were stimulated by cell stimulation cocktail with protein inhibitors, and followed by intracellular staining. (D) Fold expansion of IL-13 producing ILC2 cells after 10 days in culture. Numbers in red denote fold change of ILC2 cells recovered on day 10. (E) Fold expansion of ILC2 cells using the RosetteSep kit over 13 days in culture. (F) Contour plot of expression of CD161 and CD294 on expanded ILC2 cells on day 10. (G) Histogram of GATA3 expression by intracellular staining. Gray filled area represents control cell negative expression. (H) Contour plot of expression of amphiregulin in expanded ILC2 cells on day 14. One representative of 2 experiments. SSC-A, side scatter area.

Human ILC2 cells enriched via the RosetteSep ILC2 kit and expanded in α-MEM readily proliferate ex vivo. Enriched human ILC2 cells were cultured in α-MEM (A-B) or IMEM (C-D) media with 20% FBS, and supplemented with 20 IU/mL IL-2, 50 g/mL IL-25 and IL-33 for 10 days. While ILC2 cells are homogeneous by day 10 of expansion, for the subset of experiments where a greater number of cells was needed for downstream analyses, cultures were maintained for an additional 4 to 11 days (total 14-21 days). (A) Flow cytometric profiles of 10 days cultured human ILC2 cells. Cells were stimulated by cell stimulation cocktail with protein inhibitors followed by intracellular staining. (B) A graph showing cell numbers of IL-13-producing ILC2 cells after 10 days of culture. Numbers in red denote fold change of ILC2 cell expansion. (C) Flow cytometric profiles of 10 day cultured ILC2 cells. Cells were stimulated by cell stimulation cocktail with protein inhibitors, and followed by intracellular staining. (D) Fold expansion of IL-13 producing ILC2 cells after 10 days in culture. Numbers in red denote fold change of ILC2 cells recovered on day 10. (E) Fold expansion of ILC2 cells using the RosetteSep kit over 13 days in culture. (F) Contour plot of expression of CD161 and CD294 on expanded ILC2 cells on day 10. (G) Histogram of GATA3 expression by intracellular staining. Gray filled area represents control cell negative expression. (H) Contour plot of expression of amphiregulin in expanded ILC2 cells on day 14. One representative of 2 experiments. SSC-A, side scatter area.

Previous studies demonstrated a 10.4-fold expansion of ILC2 cells over 5 days when these cells were cultured in IMDM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 500 ng/mL, with the recombinant human cytokines IL-2, IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP, herein termed IMDM500.22 To compare our culture system with this approach, ILC2 cells enriched by the 3 described approaches were cultured in IMDM500 or α-MEM media. The IMDM500 condition did not expand ILC2 cells as robustly as α-MEM media, and gave rise to a higher percentage of IFN-γ–producing ILC1-like cells (Figure 2C-D). Next we evaluated the capacity of our system to expand ILC2 cells ex vivo. There was a 3-log expansion of ILC2 cells after 13 days (Figure 2E), with 95% of the cells expressing CD161 (KLRB1) and GATA3, but low levels of CRTH2 (prostaglandin D2 receptors; Figure 2F-G), consistent with previously reported downregulation of CRTH2 on ILC2s in culture.22 In addition, 92% of cultured ILC2 produced the EGFR ligand, amphiregulin (supplemental Figure 2B; Figure 2H).

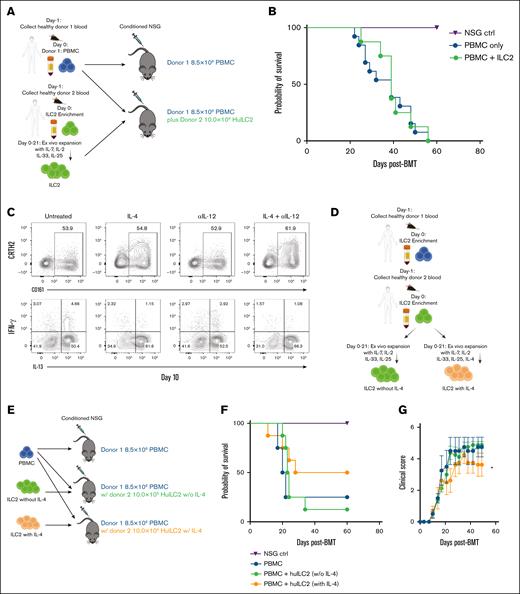

Recent studies report that constitutive activation of Notch may enhance ILC2 differentiation.23,24 Given that the OP9-DLL1 coculture system provides Notch ligand Delta-like 1 (DLL1) to activate Notch signaling pathways, we evaluated this approach to enhance ILC2 expansion. Interestingly, coculture of enriched ILC2 cells with OP9-DLL1 did not augment ILC2 yield (supplemental Figure 3A). Next we compared various cytokine combinations to identify the optimal cytokine milieu required for ILC2 expansion.25 We tested whether TSLP is required for the ex vivo expansion of circulating human ILC2s, and how exposure to TSLP affected ILC2 phenotype. ILC2 expansion was unchanged in the presence of TSLP, which also failed to augment proliferation, as >90% of cells expressed CD161, which is downregulated in proliferating ILC2 cells, regardless of the presence of TSLP (supplemental Figure 3B-D), demonstrating that TSLP is not critical for ILC2 expansion. Next, we assessed the role of IL-2 and IL-7 on ILC2 expansion. Compared with the 100-fold expansion of cells we observed in the presence of IL-2, ILC2 cells did not expand in the absence of IL-2, even in the presence of IL-7, although IL-7 did induce high levels of CRTH2 expression on ILC2 cells (supplemental Figure 3B-C). Additionally, the ability of ILC2 cells to generate cytokines was determined. Approximately 90% of ILC2s produced IL-5 and IL-13 upon phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and ionomycin stimulation in all 4 cytokine combinations (supplemental Figure 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that IL-2 is critically required for ex vivo ILC2 cell expansion. We have previously shown in murine models of allogeneic stem cell transplant that cotransplant of cultured mouse ILC2 increased survival and reduced GI tract aGVHD.16 To test the efficacy of cultured human ILC2 cells in preventing aGVHD, we used a mouse xenograft model in which NSG mice received PBMCs alone (8.5 × 106) or with cultured ILC2 that were not HLA matched with the donor PBMCs (10 × 106; Figure 3A). We found no differences in overall survival in mice that received cotransplant of unmatched ex vivo expanded ILC2 compared with T-cell controls (Figure 3B). When we examined the ILC2 product prior to infusion, we consistently found 4% to 5% of these cells expressed IFN-γ (Figure 3C). As we have found that ILC1-like ILC2 cells exacerbate GVHD in mice,26 we evaluated approaches to diminish the generation of ILC cells that express IFN-γ. The addition of IL-4 and anti-IL-12 enhanced expression of CRTH2, and reduced the number of IFN-γ–secreting cells (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 4A-C), with the addition of IL-4 having the greatest effect in suppressing the expansion of ILCs expressing IFN-γ. Thus, we expanded ILC2s in the presence of IL-4, and evaluated if this treatment improved the outcome of xenograft recipients. ILC2 cells were cultured with or without IL-4 for 15 days, and cotransplanted with unmatched PBMCs, with the primary outcomes being survival and clinical score of GVHD (Figure 3D-E). Culturing ILC2 cells with IL-4 led to a significant improvement in overall clinical score, and an improved but nonsignificant overall survival compared with ILC2 cells generated without IL-4 (Figure 3F-G). Thus, IL-4 suppression of IFN-γ by ILC2 cells was associated with improvement in clinical scores in NSG mice.

IL-4 does not affect ILC2 expansion rate, but decreases the percentage of IFN-γ–producing ILC2 cells and improves GVHD outcome. Cultured ILC2 cells were used in a xenograft GVHD model. Sublethally irradiated NSG mice received human PBMCs, with 1 group receiving donor unmatched cultured ILC2. (A) Diagram depicting PBMC isolation from donor 1, and isolation and expansion of ILC2 from donor 2, and the xenograft transplant model. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, 2 combined representative experiments using different donors is shown (n = 6 per experiment PBMC group and n = 4 per experiment ILC2 treated), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Enriched human ILC2 cells were cultured in α-MEM media as described earlier with or without the addition of 50 ng/mL IL-4 and anti-IL-12 antibody for 10 days. Representative contour plots of day 10 ILC2 cultures showing IL-13 and IFN-γ expression. (D) Diagram depicting PBMC isolation from donor 1, and enrichment of human type 2 innate lymphoid cell (HuILC2) from donor 2, and expansion with or without IL-4. (E) Diagram depicting xenotransplant using the cells described in panel D. (F) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, representative experiment using different donors and IL-4 treated or untreated ILC2 is shown (n = 4 per experiment), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (G) Clinical score of recipients from panel D, analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for repeated measures of multiple comparisons between groups, ∗P < .05. BMT, bone marrow transplantation; ctrl, control; w/o, without; w/, with.

IL-4 does not affect ILC2 expansion rate, but decreases the percentage of IFN-γ–producing ILC2 cells and improves GVHD outcome. Cultured ILC2 cells were used in a xenograft GVHD model. Sublethally irradiated NSG mice received human PBMCs, with 1 group receiving donor unmatched cultured ILC2. (A) Diagram depicting PBMC isolation from donor 1, and isolation and expansion of ILC2 from donor 2, and the xenograft transplant model. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, 2 combined representative experiments using different donors is shown (n = 6 per experiment PBMC group and n = 4 per experiment ILC2 treated), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Enriched human ILC2 cells were cultured in α-MEM media as described earlier with or without the addition of 50 ng/mL IL-4 and anti-IL-12 antibody for 10 days. Representative contour plots of day 10 ILC2 cultures showing IL-13 and IFN-γ expression. (D) Diagram depicting PBMC isolation from donor 1, and enrichment of human type 2 innate lymphoid cell (HuILC2) from donor 2, and expansion with or without IL-4. (E) Diagram depicting xenotransplant using the cells described in panel D. (F) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, representative experiment using different donors and IL-4 treated or untreated ILC2 is shown (n = 4 per experiment), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (G) Clinical score of recipients from panel D, analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for repeated measures of multiple comparisons between groups, ∗P < .05. BMT, bone marrow transplantation; ctrl, control; w/o, without; w/, with.

We next tested whether matching the HLA type of the donor and the ILC2 cells enhanced the function of ILC2 cells to prevent aGVHD (Figure 4A) by cotransplanting a single dose of IL-4-treated, donor-matched ILC2s at day 0. We observed a significant increase in overall survival of NSG recipients of ILC2s following xenotransplant, with significantly improved clinical GVHD scores beginning at day 31 (Figure 4B-D). Additionally, serum levels of TNF were significantly reduced in NSG animals that received HLA-matched ILC2s compared with the PBMC-only group (Figure 4E). Previously, we have shown that after infusion, murine ILC2 cells predominantly migrate to the lower GI tract and liver. To assess the migration of human ILC2 cells, we evaluated mice 4 days after ILC2 infusion, and no human ILC2 cells were present in the small bowel, lung, liver, or spleen. We then infused IL-33 into the mice to enhance the survival of the infused cells. We observed human ILC2 cells in the lung, liver, and spleen of NSG mice 4 days after infusion (Figure 4F; supplemental Figure 5), with very few in the GI tract. Taken together, these data indicate that HLA-matched ILC2 are more effective in suppressing GVHD in a xenograft transplant model compared with the infusion of HLA-mismatched ILC2 cells. However, human ILC2 cells either do not traffic or their persistence is decreased in the GI tract after infusion compared with murine ILC2 cells.

Cotransplant of donor-matched ILC2s reduces incidence of xeno-aGVHD following allo-HSCT. Sublethally irradiated NSG mice received human PBMCs, with 1 group receiving donor-matched cultured ILC2. (A) Diagram depicting isolation of PBMCs, and enrichment and expansion of HuILC2 from the same donor, and their use in a xenograft transplant model. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, 1 representative of 3 experiments using different donors is shown (n = 4 per experiment), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Changes in weight and (D) clinical score of recipients from panel B, analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for repeated measures of multiple comparisons, ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay quantification of human TNF in the serum of NSG recipients 28 days after transplant, represents 2 combined experiments, analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, ∗P < .05. (F) To improve ILC2 survival, NSG mice were given IL-33 1 day prior to cell infusion. Flow cytometry plots of human ILC2 in the lung and liver of NSG mice 4 days after transplant, 1 example plot each, n = 6. BMT, bone marrow transplantation; ctrl, control; SSC, side scatter; w/, with.

Cotransplant of donor-matched ILC2s reduces incidence of xeno-aGVHD following allo-HSCT. Sublethally irradiated NSG mice received human PBMCs, with 1 group receiving donor-matched cultured ILC2. (A) Diagram depicting isolation of PBMCs, and enrichment and expansion of HuILC2 from the same donor, and their use in a xenograft transplant model. (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of NSG recipient survival following transplant, 1 representative of 3 experiments using different donors is shown (n = 4 per experiment), log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Changes in weight and (D) clinical score of recipients from panel B, analyzed by 2-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni correction for repeated measures of multiple comparisons, ∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay quantification of human TNF in the serum of NSG recipients 28 days after transplant, represents 2 combined experiments, analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, ∗P < .05. (F) To improve ILC2 survival, NSG mice were given IL-33 1 day prior to cell infusion. Flow cytometry plots of human ILC2 in the lung and liver of NSG mice 4 days after transplant, 1 example plot each, n = 6. BMT, bone marrow transplantation; ctrl, control; SSC, side scatter; w/, with.

While this article was under review, and consistent with our data, Reid et al published their findings that human ILC2 cells can suppress xenograft GVHD.27 Interestingly, they described a critical role for the expression of IL-10 in the activity of ILC2 cells to prevent GVHD in the NSG model. As we had not focused on IL-10 in the function of murine ILC2 cells, we were interested in evaluating if our ILC2 cells made IL-10, or if the culture conditions used in the article from Reid et al, which did not include IL-25, were more conducive to expression of IL-10 by ILC2s. To test this, we generated ILC2 cells using the 2 different culture conditions, and evaluated each population for the expression of IL-10. As shown, we found no difference in IL-10 production by ILC2 cells between the 2 culture systems, indicating that IL-10 can be generated using our culture conditions (supplemental Figure 6).

For ILC2 cell infusions to be used clinically, the consistency of the products generated at different sites is critical. To evaluate this, RNA sequencing was used to assess the transcriptional characteristics of sorted human ILC2s immediately following RosetteSep enrichment (day 0; supplemental Figure 6A), or after 21 days of in vitro expansion. Comparisons were made between ILC2 cells isolated at the UNC-CH or the University of Minnesota (UMN; Minneapolis, MN). Isolation and enrichment of ILC2s with the RosetteSep kit at either site yielded a transcriptionally homogeneous population of cells distinct from Th cells after 14 days of culture supplemented with IL-2, IL-25, IL-33, IL-4, and IL-7 (supplemental Figure 6A; Figure 5B), with the media changed and cytokines replenished every 3 days. We generated an ILC2 RNA signature score from previously published human peripheral ILC2s, and used it to compare the expanded ILC2s generated at UNC-CH compared with UMN, and with other PB data sets.28-30 Though the ILC2s expanded ex vivo at UNC-CH and UMN have a slightly lower ILC2 signature score than the peripheral cells characterized directly ex vivo (without expansion), they segregate from ILC1 and ILC precursor populations (Figure 5B-C). To confirm the similarity between ILC2 cells generated at each site, the gene expression profiles of ILC2s expanded at UNC-CH and UMN were evaluated. Cells expanded ex vivo at both sites expressed key ILC2s lineage-defining genes (Gata3, Id2, Icos, Maf, Il1r1, Rora, and Itga3), and did not express genes important for ILC1 (Tbx21, Ncr1, Eomes) or ILC3 (Rorc) differentiation (Figure 5D).31,32 These data indicate that our approach to isolate and expand ILC2 cells was similar regardless of differences in the starting product or the site of isolation.

Multiomic sequencing characterization of ex vivo expanded human ILC2 cells. (A) Schematic of ex vivo 14 day expansion of peripheral human ILC2s from distinct donors. Cells from 2 different donors (A and B) were enriched via RosetteSep, and expanded in complete α-MEM media with 10 to 50 ng/mL IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33. (B) The transcriptome(s) of ILC2s generated across both sites were compared with those of ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC precursors from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.28 Comparisons were calculated by scoring based on signatures derived from 2 previously published characterizations of ILC2s, as well as a merged score.26,27 Gene signatures were calculated using Bioconductor’s singscore (V.1.4.0) simpleScore function. (C) Heat map depicting the expression of ILC2 lineage-defining genes between UNC-CH- and UMN-derived samples expanded after RosetteSep, and subsequent culture in α-MEM with IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33 for 14 days at each site. (D) Comparison of the similarity of ILC2s generated as described earlier at UNC-CH or UMN to the transcriptional landscape of human Th1, Th2, or Th17 subsets from healthy donors as presented in other PB data sets. (E-F) Representative tracks of normalized ATAC signal from samples expanded at UNC-CH on day 0 (E), or day 21 (F) at ILC1- (Tbx21 and Ifng), ILC2- (Gata3 and Il13), and ILC3-associated (Rorc and Il17a) gene loci. Tick marks indicate specific locations of differential relative chromatin accessibility (RCA) peaks. (G) Peaks detected by MACS2 and matched by HOMER to the 6 genes of interest in panels E-F (not filtered or weighted by distance to nearest transcriptional start site [TSS] or by peak score). (H) HOMER motif output for day 21 vs day 0 samples (sequence logo). Analysis was performed by finding differential expression by feature count of consensus peaks between all samples, and filtering to only include peaks that had ≥2.0 log2 fold change in day 21 samples, then finding motifs within those peaks.

Multiomic sequencing characterization of ex vivo expanded human ILC2 cells. (A) Schematic of ex vivo 14 day expansion of peripheral human ILC2s from distinct donors. Cells from 2 different donors (A and B) were enriched via RosetteSep, and expanded in complete α-MEM media with 10 to 50 ng/mL IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33. (B) The transcriptome(s) of ILC2s generated across both sites were compared with those of ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC precursors from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.28 Comparisons were calculated by scoring based on signatures derived from 2 previously published characterizations of ILC2s, as well as a merged score.26,27 Gene signatures were calculated using Bioconductor’s singscore (V.1.4.0) simpleScore function. (C) Heat map depicting the expression of ILC2 lineage-defining genes between UNC-CH- and UMN-derived samples expanded after RosetteSep, and subsequent culture in α-MEM with IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33 for 14 days at each site. (D) Comparison of the similarity of ILC2s generated as described earlier at UNC-CH or UMN to the transcriptional landscape of human Th1, Th2, or Th17 subsets from healthy donors as presented in other PB data sets. (E-F) Representative tracks of normalized ATAC signal from samples expanded at UNC-CH on day 0 (E), or day 21 (F) at ILC1- (Tbx21 and Ifng), ILC2- (Gata3 and Il13), and ILC3-associated (Rorc and Il17a) gene loci. Tick marks indicate specific locations of differential relative chromatin accessibility (RCA) peaks. (G) Peaks detected by MACS2 and matched by HOMER to the 6 genes of interest in panels E-F (not filtered or weighted by distance to nearest transcriptional start site [TSS] or by peak score). (H) HOMER motif output for day 21 vs day 0 samples (sequence logo). Analysis was performed by finding differential expression by feature count of consensus peaks between all samples, and filtering to only include peaks that had ≥2.0 log2 fold change in day 21 samples, then finding motifs within those peaks.

Next, chromatin accessibility at key ILC2 loci in ILC2s on day 0 and after 3 weeks of expansion was evaluated, which allowed us to compare terminally expanded (day 21) vs the initial (day 0) cell populations. To characterize the cells enriched by the RosetteSep kit, ATAC sequencing was performed from viable, lineage-negative, CD127+ cells immediately following processing with the RosetteSep kit. For comparison, cells were harvested after 21 days of growth in α-MEM, and purity of lineage-negative cells was checked prior to chromatin isolation and transposition. Corresponding with the presence of ILC2-associated gene expression signatures (Figure 5C), ATAC sequencing revealed regions of accessible chromatin at both the Gata3 and Il13 loci on day 0, with increasing motif accessibility at these sites over 3 weeks of culture (Figure 5E-G). Importantly, there was much less chromatin accessibility at the Tbx21 or Ifng loci, which, respectively, encode for Tbet and IFN-γ, and are required for ILC1 development. Furthermore, there was no increase in accessible chromatin at ILC3-associated loci, including Rorc and Il17a over the culture period (Figure 5G). Finally, we assessed the motifs with the greatest change in our ILC2s to evaluate the genes with the greatest change in chromatin accessibility during 3 weeks in culture. We did not identify any ILC1-associated gene motifs among the topmost differentially accessible transcription factor binding sites between days 0 and 21 (Figure 5H).

Taken together, profiling of the transcriptome and chromatin landscape of these cells confirms that RosetteSep enrichment followed by expansion in α-MEM media at 2 different sites generated a population of transcriptionally similar ILC2s, with the cells expanded at UNC-CH having a chromatin accessibility landscape found previously in ILC2 cells.

Discussion

Clinical outcomes of patients with treatment refractory aGVHD of the lower GI tract are suboptimal, with most patients who fail corticosteroids and JAK inhibitors succumbing to disease after 1 year.33 A significant number of third-line approaches for therapy have been attempted without clear clinical benefit. Our group and others have focused on approaches to enhance GI tract repair to improve the outcome of aGVHD of the GI tract,5,16,34 with our work focusing on the important role proteins that maintain intestinal stem cells and induce tissue repair play in the GI tract. Our work has identified the EGFR ligand amphiregulin as critical to GI tract repair in murine GVHD models. Previously, a critical role for amphiregulin production by ILC2 cells in the ability of those cells to prevent aGVHD in the lower GI tract was shown by our group.16 This led us in the current work to evaluate human ILC2 cells that could have a similar impact on GI tract aGVHD morbidity and mortality. Here, we demonstrate that ILC2 cells can be isolated and enriched from PBMCs, this is enhanced using the RosetteSep kit, leading to robust expansion over 2 to 3 weeks in culture. We also show that the expansion of ILC1-like cells can be suppressed by expanding ILC2 cells in the presence of IL-4, and that these ILC2s decrease the severity of xenogeneic GVHD, with a significant reduction in serum levels of TNF in mice receiving ILC2 cells. These findings set the stage for phase 1 studies to evaluate the function of ILC2 cells in the treatment of GI tract aGVHD.

Herein, we compared our approach to the isolation and expansion of human ILC2s with a previously published approach, and demonstrate more robust and stable expansion of cells using our culture system. IMDM media differs from α-MEM in several ways, including additional amino acids, selenium, and the inclusion of enhanced buffering with HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-Nʹ-2-ethanesulfonic acid) and sodium pyruvate. As a result, this media is formulated to improve the expansion of adaptive immune cells. Why α-MEM functions better to support the expansion of ILC2 cells is not clear, with our current hypothesis focusing on the function of amino acids as an energy source for ILC2 expansion to be evaluated in future work.

Our approach to expanding ILC2 cells was robust as we were able to get approximately a 3-log expansion in cells over 2 weeks in culture. These cells could be expanded similarly at 2 different institutions, with RNA sequencing demonstrating similar expression patterns of canonical ILC2 gene signatures when expanded at the UNC-CH or UMN. Interestingly, we found that 1% to 3% of the cells expanded had a genomic profile like ILC1-like cells. The infusion of ILCs, where 4% to 5% of the product expressed IFN-γ, did not improve survival when these cells were given to NSG mice, leading us to evaluate approaches to limit the expansion of these cells. The addition of α-IL-12 antibody and IL-4 ex vivo limited the growth of ILC1-like cells. Given our interest in the potential downstream clinical application of these cells, we utilized IL-4, which is available as a guanosine monophosphate-reagent, to block the conversion of ILC2 cells. This suppressed the generation of ILC1-like cells and decreased the clinical score of aGVHD, and improved the median survival of NSG mice after allogeneic stem cell transplant when given with ex vivo HLA-matched expanded ILC2 cells.

Previously, we found in an immune-competent mouse model that donor ILC2 cells preferentially migrated to the colon and small bowel, and were effective in the prevention and treatment of GI tract GVHD.16,26 In contrast, in this xenogeneic transplant model, human ILC2s were able to reduce the severity of GVHD when given prophylactically, but were not as effective as murine ILC2s in the immune-competent model. There are multiple hypotheses for the more modest activity of donor ILC2 in the xenogeneic GVHD model. Unlike our murine models where overall survival and clinical GVHD score are dominated by the development of GI tract GVHD, mortality and morbidity in our xenogeneic model is driven by pathology in the liver and lung. We can demonstrate donor ILC2s in the GI tract and liver for at least 4 weeks after infusion in the immune-competent model. In contrast, human ILCs are present for <1 week in the xenogeneic model, which may be in part due to the absence of human cytokines such as IL-33 critical for the maintenance of human ILC2s in that model. When we compare the expression of trafficking receptors to the GI tract between the murine and human ILC2s, no significant difference was found.16,26 This suggests that the limited persistence of human ILC2s in the xenogeneic model is more dependent on their modest persistence.

In summary, we have generated a novel approach to rapidly expand ILC2 cells that limits the expansion of ILC1-like cells and can be rapidly taken to the clinic. These studies provide the foundation to determine if enhancing GI tract barrier repair by the infusion of ILC2 cells improves the outcome for patients with treatment-refractory aGVHD of the lower GI tract.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janet Dow at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Flow Cytometry Core Facility for cell sorting assistance and guidance. The authors also thank Ivan Maillard at the University of Pennsylvania for providing OP9-DLL1 cells. The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support from the UNC High Throughput Sequencing Facility.

S.J.L. was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K12 GM000678 and T32 CA211056. B.R.B. was supported by NIH grants R37 AI34495 and R01 HL11879. J.S.S. from UNC at Chapel Hill School of Medicine is supported by NIH grants 1R01 HL139730- and 1R01 HL155098. The UNC Flow Cytometry Core Facility is supported, in part, by Cancer Center Core Support grant P30 CA016086 to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by Center for AIDS Research award P30 AI050410 and North Carolina Biotech Center Institutional Support grant 2012-IDG-1006. The UNC High Throughput Sequencing Facility is supported by the University Cancer Research Fund, Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Support grant P30 CA016086, and UNC Center for Mental Health and Susceptibility grant P30 ES010126.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: D.W.B., S.J.L., Y.X., and J.S.S. wrote the manuscript; Y.X., B.R.B., and H.E.S. developed the human type 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) ex vivo isolation and expansion method; D.W.B., S.J.L., Y.X., H.E.S., and B.R.B. optimized in vitro ILC2 enrichment assays and cell culture; D.W.B. and K.L.H. performed xenotransplants; A.D.W. and M.G.W. performed transcriptomics analysis; A.D.W. performed chromatin analysis; S.J.L. oversaw transcriptional and chromatin analyses; K.P.M. and J.M.C. advised on human cell culture and xenotransplant; and B.R.B. and J.S.S. contributed as the lead investigators.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.S.S. reports research funding from Merck Inc, Carisma Therapeutics, and GlaxoSmithKline; and is a compensated consultant for Pique Therapeutics. B.R.B. reports remuneration as an advisor to BlueRock Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology, Sanofi, Legend Biotech, GentiBio, and Incyte; and research funding from BlueRock Therapeutics, Rheos Medicines, and Carisma Therapeutics, Inc. J.S.S. and D.W.B. report intellectual property (patent 16/598914). D.W.B., H.E.S., J.M.C., J.S.S., and B.R.B. disclose intellectual property (patent 11471517). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonathan S. Serody, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Marsico Hall, Room 5012, 125 Mason Farm Rd, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7295; email: jonathan_serody@med.unc.edu.

References

Author notes

D.W.B., S.J.L., and Y.X. contributed equally to this work.

B.R.B. and J.S.S. contributed equally to this work.

ATAC sequencing and RNA sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession numbers GEO301227 and GEO301228, respectively).

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Jonathan S. Serody (jonathan_serody@med.unc.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Multiomic sequencing characterization of ex vivo expanded human ILC2 cells. (A) Schematic of ex vivo 14 day expansion of peripheral human ILC2s from distinct donors. Cells from 2 different donors (A and B) were enriched via RosetteSep, and expanded in complete α-MEM media with 10 to 50 ng/mL IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33. (B) The transcriptome(s) of ILC2s generated across both sites were compared with those of ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC precursors from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.28 Comparisons were calculated by scoring based on signatures derived from 2 previously published characterizations of ILC2s, as well as a merged score.26,27 Gene signatures were calculated using Bioconductor’s singscore (V.1.4.0) simpleScore function. (C) Heat map depicting the expression of ILC2 lineage-defining genes between UNC-CH- and UMN-derived samples expanded after RosetteSep, and subsequent culture in α-MEM with IL-7, IL-2, IL-4, IL-25, and IL-33 for 14 days at each site. (D) Comparison of the similarity of ILC2s generated as described earlier at UNC-CH or UMN to the transcriptional landscape of human Th1, Th2, or Th17 subsets from healthy donors as presented in other PB data sets. (E-F) Representative tracks of normalized ATAC signal from samples expanded at UNC-CH on day 0 (E), or day 21 (F) at ILC1- (Tbx21 and Ifng), ILC2- (Gata3 and Il13), and ILC3-associated (Rorc and Il17a) gene loci. Tick marks indicate specific locations of differential relative chromatin accessibility (RCA) peaks. (G) Peaks detected by MACS2 and matched by HOMER to the 6 genes of interest in panels E-F (not filtered or weighted by distance to nearest transcriptional start site [TSS] or by peak score). (H) HOMER motif output for day 21 vs day 0 samples (sequence logo). Analysis was performed by finding differential expression by feature count of consensus peaks between all samples, and filtering to only include peaks that had ≥2.0 log2 fold change in day 21 samples, then finding motifs within those peaks.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/9/19/10.1182_bloodadvances.2024013609/2/m_blooda_adv-2024-013609-gr5.jpeg?Expires=1770092956&Signature=T7es8lh69HJdxXGcLGycz9izencyr-zijlFr5oY6raEJ5OJx9qei5xAtkQgBX7r4EmmiL-ZjKV5Fw0lR14KGLYlSkVPfOJqZmGLoIPw~U-LKisa3UsFSUpMiIDTa6zKF0REzaJLnM20fOef4FjD6PF6YEDvg2z2cYMQbL9R1s58ls7d0xGyZi35WAsENk7oBhmSsPRWXaQUlOzpc5Xjn9RW19wyfVyaBHQcwtZmosCZw9Hsinjw7cb9shlcjE3l4nrTZcYWS2OxSDaPHeMgyjIxq11En5pxGOG9dY8oeGZdVqQYso8IL9bcFfbS9NvNDPZVrQEeXKAZrt500tjZF2g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)