TO THE EDITOR:

First-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) continues to evolve. Over the last 5 years, randomized phase 3 trials have compared a variety of traditional chemoimmunotherapy regimens with novel treatment approaches targeting Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKI) and BCL-2 alone or in combination.1-7 These phase 3 trials have consistently demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) with novel therapy approaches.

We reported the first phase 3 comparison of the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib in combination with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody with the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) chemoimmunotherapy regimen, the historical gold standard treatment for CLL.1,2 After a median follow-up of 70 months, ibrutinib-based treatment demonstrated superior PFS relative to FCR in both immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGHV)–mutated (M) and IGHV–unmutated (UM) patients.2 Here, we report on the long-term tolerability and efficacy in 354 patients randomized to the ibrutinib arm of the E1912 trial after a median follow-up of 8.2 years.

The details of the E1912 trial have been previously reported (Clinical Trial #NCT02048813).1,2 After providing written informed consent, previously untreated patients with CLL aged ≤70 years without deletion 17p13 on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and in need of treatment according to International Workshop on CLL (iwCLL) criteria8 were randomized in a 1:2 manner to either 6 cycles of FCR9,10 or 6 cycles of ibrutinib and rituximab, followed by continued ibrutinib until disease progression or unmanageable toxicity. The National Cancer Institute Central Institutional Review Board as well as local institutional review boards, as required by treating institutions, approved the study in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

PFS, defined as the time from randomization to progression or death without documented progression, was the primary trial end point. Patients alive without documented progression were censored at the time of last disease evaluation. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate time-to-event distributions. Log-rank tests were used to compare PFS by IGHV mutation status. P values are 2-sided and were not corrected for multiple testing.

This analysis incorporates follow-up for patients randomized to the ibrutinib and rituximab arm of the E1912 trial through 1 January 2024. The median follow-up for patients in the ibrutinib arm as of this date was 8.2 years (98 months; range, 0-116).

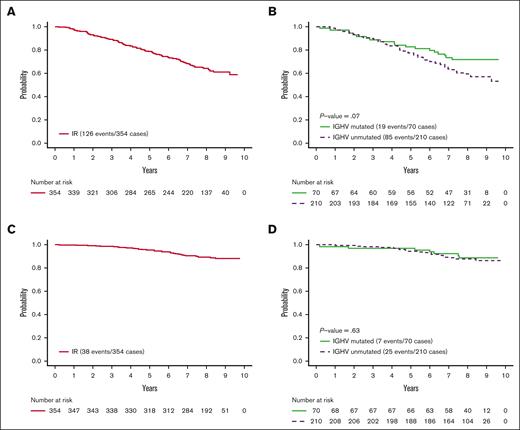

As of last follow-up, 149 of 352 patients (42.3%) remain on active treatment with ibrutinib (supplemental Figure 1). Eight-year PFS for the ibrutinib arm was 64.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 59.4-69.8; Figure 1A). The 8-year PFS of IGHV-UM patients was 59.4% (95% CI, 52.9-66.7) compared with 71.8% (95% CI, 61.7-83.4) for IGHV–M patients (P = .07; Figure 1B). Overall survival for all patients and by IGHV mutation status is provided in the supplemental Figures 2 and 3.

PFS. (A) PFS of patients randomized to ibrutinib-rituximab (IR) arm of E1912 trial. (B) PFS of IR arm of E1912 trial by IGHV mutation status. (C) PFS of patients while on treatment; all patients on the IR arm of E1912 trial. Patients discontinuing ibrutinib for reason other than progression or death are censored at the time of off treatment. (D) PFS while on treatment for IR arm of E1912 trial by IGHV mutation status. Patients discontinuing ibrutinib for reason other than progression or death are censored at the time of off treatment.

PFS. (A) PFS of patients randomized to ibrutinib-rituximab (IR) arm of E1912 trial. (B) PFS of IR arm of E1912 trial by IGHV mutation status. (C) PFS of patients while on treatment; all patients on the IR arm of E1912 trial. Patients discontinuing ibrutinib for reason other than progression or death are censored at the time of off treatment. (D) PFS while on treatment for IR arm of E1912 trial by IGHV mutation status. Patients discontinuing ibrutinib for reason other than progression or death are censored at the time of off treatment.

We next analyzed PFS while on ibrutinib treatment. For this analysis, patients discontinuing ibrutinib for a reason other than progression or death were censored at the time they went off treatment. Eight-year PFS in this subset analysis was 78.8% (95% CI, 73.9-84.0; Figure 1C). In this analysis, the 8-year PFS for IGHV–UM patients was 75.0% (95% CI, 68.3-82.4) and 79.1% (95% CI, 68.7-91.0; Figure 1D) for IGHV–M patients. These data suggest that, as long as patients remain on therapy, there does not appear to be a substantial difference between PFS among IGHV–M and –UM patients. Estimated PFS while on ibrutinib by FISH risk category is shown in the supplemental Figure 4.

The estimated probability of remaining on treatment at 8 years was 46.1% (95% CI, 41.1-51.8). Among the 149 patients still on ibrutinib, 131 (87.9%) remain on full dose. Among the 203 patients who discontinued ibrutinib treatment, 58 (28.6%) discontinued due to disease progression (n = 46) or death (n = 12); 89 (43.8%) discontinued for adverse events (AEs)/toxicity; 21 (10.3%) discontinued for other health problem(s); and 35 (17.2%) due to patient withdrawal or refusal to continue treatment. Among the 145 patients who discontinued treatment for a reason other than progression or death, 121 received a reduced ibrutinib dose before discontinuation. With respect to adherence, 351 of 352 patients returned pill bottles or diaries detailing adherence for at least 1 cycle. Among these individuals, the average percentage of cycles for which pill bottles or diaries were available was 96.7%. The median of average percent adherence of prescribed dose per patient was 97.6% (first quartile 95.7%; third quartile 98.9%).

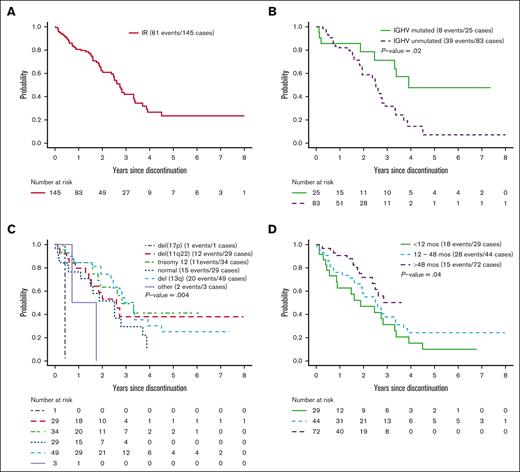

We next evaluated PFS from the time of discontinuation of ibrutinib for a reason other than progression or death. Six patients who discontinued ibrutinib but received nonprotocol therapy before disease progression were censored at the start of nonprotocol therapy. Among the 145 patients who discontinued ibrutinib for a reason other than progression or death, the median time on ibrutinib was 47.7 months (range, 0.2-111.1). The median PFS from the time ibrutinib was discontinued for a reason other than progression or death was ∼2.7 years (Figure 2A). Treatment discontinuation for a reason other than progression or death was associated with shorter PFS (hazard ratio, 8.1; 95% CI, 5.4-12.0; P < .001); however, dose reductions were not associated with PFS. This result may be due to the small percentage of days patients were on reduced dose. The median percentage of treatment days patients received a dose of ≤280 mg before discontinuing treatment was 2.8% (quartile 1 [Q1], 0.27%; quartile 3 [Q3], 20.2%). PFS from the time of discontinuation of ibrutinib was shorter for IGHV–UM patients (median, 2.5 years) relative to IGHV–M patients (median, 3.9 years; P = .02; Figure 2B). PFS from the time of discontinuation of ibrutinib by FISH risk category is shown in Figure 2C.

PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation. All patients on the IR arm of E1912 trial who started IR treatment (patients who did not start IR were excluded). Patients who started alternative therapy censored at the time of starting alternative therapy. (A) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation. (B) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by IGHV status. (C) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by Döhner classification. (D) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by duration of ibrutinib treatment before discontinuation.

PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation. All patients on the IR arm of E1912 trial who started IR treatment (patients who did not start IR were excluded). Patients who started alternative therapy censored at the time of starting alternative therapy. (A) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation. (B) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by IGHV status. (C) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by Döhner classification. (D) PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation by duration of ibrutinib treatment before discontinuation.

We next evaluated PFS after ibrutinib discontinuation based on the duration of ibrutinib exposure. Among patients receiving <12 months (n = 29), 12 to 48 months (n = 44), and >48 months (n = 72) of ibrutinib before discontinuation, the median PFS after discontinuation of ibrutinib was 22.5 months, 30.3 months, and not yet reached, respectively (P = .04; Figure 2D).

These overall results suggest long-term ibrutinib continues to be a well-tolerated first-line therapy in patients with CLL aged <70 years and results in durable disease control for both IGHV–M and –UM patients. After a median follow-up of >8 years, the median PFS for all patients treated on the ibrutinib arm of the E1912 trial has not been reached. The PFS for patients able to remain on ibrutinib is even higher, with ∼8 of 10 patients progression-free at the 8-year mark and no statistically significant difference by IGHV status.

Although these results are encouraging, slightly less than half of patients remain on ibrutinib after 8 years of follow-up. It is noteworthy that this discontinuation rate for a reason other than progression or death in E1912 is almost identical to RESONATE-2 (RESONATE-2, 24%; E1912, 25.3%), despite the age difference between the 2 cohorts (median age RESONATE-2, 73 years; E1912, 57 years).

The majority of patients (71.4%) who discontinued ibrutinib treatment in the E1912 trial did so for a reason other than progression or death. Among patients randomized to ibrutinib, 89 of 352 (25.3%) who started ibrutinib discontinued treatment due to toxicity/AE. An additional 35 of 352 (9.9%) discontinued treatment due to patient choice (ie, patient withdrawal or refusal). It is hoped, but yet to be determined, whether second-generation BTK inhibitors, which have demonstrated more favorable toxicity profiles, may increase the proportion of patients able to remain on BTK inhibitor treatment longer term.

Although long-term disease control is better among patients who remain on ibrutinib, time to progression after discontinuing ibrutinib for a reason other than progression or death is still measured in years. Among those who stop ibrutinib for a reason other than progression/death, the duration of ibrutinib exposure before discontinuation appears to affect PFS. In contrast, dose reductions were not associated with shorter PFS in this analysis. It should be noted that, at the time of progression, most patients have asymptomatic lymphocytosis and may not require retreatment for several additional years. Nonetheless, these data may increase motivation to try to keep IGHV–UM patients experiencing AE on treatment using strategies such as dose reduction and/or changing to alternative BTKI.

A number of recent trials have begun to evaluate time-limited treatments. These approaches have used either the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in combination with anti-CD20 therapy5,11 or BTKI-BCL-2 inhibitor combinations11-13 with the goal of achieving deep and durable disease control with time-limited treatment. These treatment strategies eliminate the need for chronic, indefinite treatment and have great appeal to many patients, as well as economic benefits to both patients and society, given the high current cost of continuous BTK inhibitor–based therapy. Studies to date for these fixed-duration treatments have been favorable.11-13 The present results from the E1912 trial with >8 years of follow-up indicate, however, that it will be difficult to achieve superior disease control to first-line treatment with chronic, indefinite BTKI, especially if better-tolerated BTKIs enable a higher proportion of patients to remain on treatment for a longer interval.

Acknowledgments: This study was conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group - American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ECOG-ACRIN) Cancer Research Group (Peter J. O'Dwyer and Mitchell D. Schnall) and supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health under the following award numbers: U10CA180794, U10CA180821, U10CA180820, U10CA180888, UG1CA189859, UG1CA189863, UG1CA190140, UG1CA232760, UG1CA233180, UG1CA233230, UG1CA233253, UG1CA233290, and UG1CA233339. Correlative studies were supported by R01 CA193541 and CA251801.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contribution: T.D.S., X.V.W., and N.E.K. designed the research; T.D.S., X.V.W., C.A.H., E.P., S.O., J.B., D.F.J., J.F.L., C.C.Z., P.M.B., A.F.C., A.R.M., A.K.S., M.P.M., R.F.L., H.E., R.M.S., M.L., M.T., and N.E.K. performed the research; T.D.S., X.V.W., C.A.H., E.P., S.O., J.B., D.F.J., J.F.L., C.C.Z., P.M.B., A.F.C., A.R.M., A.K.S., M.P.M., R.F.L., H.E., R.M.S., M.L., M.T., and N.E.K. contributed patients or analytical tools; X.V.W. analyzed the data; T.D.S. and X.V.W. wrote the manuscript; and C.A.H., E.P., S.O., J.B., D.F.J., J.F.L., C.C.Z., P.M.B., A.F.C., A.R.M., A.K.S., M.P.M., R.F.L., H.E., R.M.S., M.L., M.T., and N.E.K provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.D.S. reports receiving grant support from Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, and Genentech; and holding a patent (US14/292075) on green tea extract epigallocatechin gallate in combination with chemotherapy for CLL. N.E.K. reports serving on the advisory board for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Behring, CytomX Therapeutics, Dava Oncology, Janssen, Juno Therapeutics, ONCOtracker, Pharmacyclics, and Targeted Oncology; serving on the data safety monitoring committee for Agios Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)-Celgene, CytomX Therapeutics, Janssen, MorphoSys, and Rigel; and research funding from AbbVie, Acerta Pharma, BMS, Celgene, Genentech, MEI Pharma, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis, TG Therapeutics, and Tolero Pharmaceuticals. A.R.M. reports research support from TG Therapeutics, Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, Acerta, AZ, Regeneron, DTRM Biopharma, Sunesis, Loxo Oncology, and Adaptive; and advisory/consultancy/data safety monitoring board fees from TG Therapeutics, Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, Acerta, AstraZeneca, DTRM Biopharma, Sunesis, and Adaptive. S.O. reports research support from Kite, Regeneron, Nurix, and Mustang Bio; consultant fees and research support from Caribou, Gilead, Pharmacyclics, TG Therapeutics, and Pfizer; and consultancy for GSK, Janssen Oncology, Vaniam Group LLC, Autolus, Johnson & Johnson, Secura Bio, AstraZeneca, and Pharmacyclics/AbbVie. J.B. reports grant support and advisory board fees from Pharmacyclics-AbbVie; and lecture fees and travel support from Janssen, Gilead Sciences, and Genentech. P.M.B. reports consulting for Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Genentech, Gilead, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Merck, Celgene/BMS, MorphoSys, TG Therapeutics, and Seattle Genetics. A.F.C. reports research funding from Secura Bio. A.R.M. reports grant support, consulting fees, fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board, and advisory board fees from TG Therapeutics; grant support, consulting fees, and advisory board fees from Pharmacyclics, Johnson & Johnson, AbbVie, and AstraZeneca; grant support from Regeneron; fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board and advisory board fees from Celgene; grant support and advisory board fees from Sunesis Pharmaceuticals and Loxo Oncology; and lecture fees, fees for continuing medical education events, and other events from prIME Oncology. H.E. reports research funding from AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Forma, Forty Seven/Gilead, GlycoMimetics, ImmunoGen, Jazz, MacroGenics, and Novartis; advisory board fees from AbbVie, Agios, Astellas, Celgene/BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, GlycoMimetics, Incyte, Jazz, Kura Oncology, Novartis, Takeda, and Trillium; speakers bureau fees from AbbVie, Agios, Amgen Celgene/BMS, Incyte, Jazz, and Novartis; and financial or material support from AbbVie (Chair, Independent Review Committee for VIALE A and VIALE C) and Celgene/BMS (Chair, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) Repository Study). M.T. reports research funding from AbbVie, Cellerant, Orsenix, ADC Therapeutics, BioSight, GlycoMimetics, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; advisory board fees from AbbVie, BioLineRx, Daiichi Sankyo, Orsenix, KAHR, Rigel, Nohla, Delta-Fly Pharma, Tetraphase, Oncolyze, Jazz Pharma, Roche, BioSight, and Novartis; and royalties from UpToDate. R.M.S. reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Agios, and Novartis; grants from Arog; and personal fees from Actinium, Argenx, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BioLineRx, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Elevate, GEMoaB, Janssen, Jazz, MacroGenics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Hoffman LaRoche, Stemline, Syndax, Syntrix, Syros, Takeda, and Trovagene, outside the submitted work. M.L. reports grant support and consulting fees from Amgen; grant support from Astellas Pharma, AbbVie, Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pluristem Therapeutics; and consulting fees from Sanofi and NewLink Genetics. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tait D. Shanafelt, Division of Hematology, Stanford University School of Medicine, 500 Pasteur Dr, Suite P354, Stanford, CA 94025; email: tshana@stanford.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request through the National Clinical Trials Network Data Archive.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.