Key Points

Patients with CLL are interested in learning about the disease and its care and most would like to participate in treatment decisions.

This survey identified unmet global needs in CLL and can guide patient education targets for clinicians, advocates, and policymakers.

Abstract

The Virtual Opinions poll Independent Centered on CLL patients’ Experience (VOICE) evaluated patients’ knowledge about chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), their perspectives on diagnosis and treatment, and their unmet needs. Clinicians and patient advocacy group representatives developed and distributed the survey from March through December 2022 in 12 countries, and 377 patients with ≥1 line of previous CLL treatment responded from Europe, Latin America, the United States, Australia, Egypt, and Turkey. A majority of them (90%; 336/374) relied on their physicians for information regarding CLL and treatment. If at high risk, respondents prefer oral medications to intravenous (78%; 232/296), fixed duration treatment over treatment until progression (69%; 185/270), outpatient over inpatient treatments (91%; 257/283). Over three-fourths of respondents (78%; 286/368) wanted to be involved in treatment decisions, but a minority actually participated (44%; 138/313). COVID-19 vaccinations were widely available (97%; 273/281), but one-fifth (19%; 63/331) were unaware that CLL increases vulnerability to infections. Most patients’ physicians explained their treatment options (84%; 297/355), and 90% (271/301) understood their treatment. Notably, >10% would continue treatment normally if they experienced cardiac problems or arrhythmias, whereas 23% would consider stopping treatment if they developed skin cancer. Treatment–associated side effects affected 27% to 43% of patients. These results in a global patient population highlight gaps in patients’ knowledge of risk groups, their susceptibility to infections including COVID, and the side effects of common treatments. Such knowledge can guide the appropriate targeting of patient education initiatives by clinicians, advocates, and policymakers.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is 1 of the most common lymphoid cancers and predominantly affects older people.1 The Global Burden of Disease study in 2019 showed that the incidence of CLL has increased globally from 40 537 cases in 1990 to 103 467 in 2019, and global deaths have risen from 21 548 in 1990 to 44 613 in 2019, an increase of 107%.2,3 The number of people living with CLL is increasing and estimated to reach 199 000 in the United States by 2025.4 This increase is due in part to the introduction of oral targeted therapies, which have improved overall survival and lengthened the duration of treatment but are substantially more costly than chemoimmunotherapy.5,6

Patients with CLL are predominantly older; the median age at diagnosis in the United States is 70 years,7 and globally, the highest incidence is in people aged >70 years.3 In addition to the morbidity and mortality associated with CLL, patients also face a variety of adverse events (AEs) associated with the treatments for this disease, including gastrointestinal and cardiovascular complications, cytopenias, and bleeding infections. These treatment-related AEs are associated with substantial financial costs, which can exceed $6000 per month in the Unites States.8 Moreover, older patients are more at risk of AEs from CLL treatment owing to age-related physiological changes, and they are at increased risk of drug-drug interactions owing to higher rates of polypharmacy.9

Another challenge related to CLL is that health literacy decreases with advancing age partly because of declining cognition and memory.10 Because patients with CLL on an average are older, decreased health literacy might affect their understanding of CLL.11 Although several regional surveys have been conducted on the perspectives of patients with CLL, including in the United States, India, and Europe,12-15 there is little evidence in the medical literature regarding patients’ understanding of their condition and their attitudes regarding diagnosis and treatment. This study was intended to address that lack of evidence using an anonymous questionnaire and respondents from around the world, including outside of North America and Europe, to better understand what they know about their disease, their perspectives on diagnosis and treatment, and assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their lives. The data collected could help identify knowledge gaps to be addressed in patient education, ways to deliver information that patients are receptive to, and region-specific needs in different areas of the world.

Methods

A steering committee of clinicians and representatives of patient advocacy groups (PAGs) including the Associação Brasileira de Linfoma e Leucemia (ABRALE) from Brazil, the Asociación Leucemia Mieloide Argentina from Argentina, and the Leukaemia Foundation from Australia developed the survey. All members of the committee provided input and approved the final survey. This cross-sectional survey was anonymous and included no patient-identifying information. Ethical approval was not required in many cases because of the anonymous nature of the survey; however, approval was sought and obtained on a hospital-by-hospital basis, whenever required.

The survey was distributed from March through December 2022 and queried patients on following 4 primary areas: (1) patients’ awareness of different risk groups and the role of the patient in treatment decisions, (2) impact of COVID-19 on patients, (3) patients’ knowledge of the side effects associated with treatments of CLL, and (4) patients’ reasons for stopping treatment.

The survey was available in the following 6 languages: English, Czech, Arabic, Spanish, Portuguese, and Turkish. Patients who were undergoing treatment for CLL or who were previously treated were eligible to complete the survey.

Invitations to register for the survey were distributed by members of the steering committee and other health care providers directly to their patients. The involved PAGs also distributed survey invitations to their members and made it available in online for patients with CLL. In addition, social media platforms were used to distribute survey invitations, including Facebook and LinkedIn. Finally, a dedicated website was available for patients to register and complete the survey online at https://cll-survey-registration.abplatforms.com/. After registration, the survey could be completed via this online platform, by emailing their responses to the survey organizers, or by completing and mailing a printed copy. The survey could be completed by patients independently or with assistance from their caregivers.

Results

Study population

A total of 445 participants registered to take the survey, and 377 patients (85%) from Latin America, Europe, Turkey, Australia, Egypt, and the United States completed the survey by the data cutoff date in December 2022 (supplemental Table 1). Respondents were predominantly treated at academic or university hospitals or public tertiary care centers (92%; 244/264). Some questions were optional for patients to complete and not all patients finished the survey completely; therefore, the number of responses varies for each question. Although the survey did not directly ask respondents about the treatments that they received, all major classes of treatment asked about in the survey were available in all the countries in the survey, including chemoimmunotherapy (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab), first-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib), second-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib), and B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors (venetoclax).16-28

Patients’ awareness of different risk groups and the role of the patient in treatment

Heterogeneity of CLL

Table 1 shows survey questions probing respondents’ knowledge about risk groups used to stratify patients into groups at higher or lower risk of CLL progression. Almost two-thirds (60%; 228/377) were unaware or unsure of the existence of different risk groups, and 74% (236/320) reported they had not received relevant information from educational courses or were unsure if they had. Similarly, 65% of respondents (203/312) lacked awareness or were unsure about laboratory tests to determine risk, and 74% (242/328) did not know or were unsure about the treatment implications of different risk levels. Testing all patients for risk group status was supported by most respondents (70%; 261/373). If they were patients at high risk, respondents would prefer oral medications to IV (78%; 232/296) and fixed duration treatment over treatment until progression (69%; 185/270). Finally, most respondents (91%; 257/283) would prefer outpatient over inpatient treatments.

Patients’ view of the heterogeneity of CLL

| Question . | N . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you know about the different risk groups of patients with CLL? | 377 | 149 (40) | 141 (37) | 87 (23) |

| In the educational courses∗, did you receive any information to help you understand the different risk groups of patients with CLL? | 320 | 84 (26) | 194 (61) | 42 (13) |

| Do you know about any laboratory tests to identify each patient’s risk level? | 312 | 109 (35) | 166 (53) | 37 (12) |

| Do you know about any treatment differences between the different CLL risk groups? | 328 | 86 (26) | 160 (49) | 82 (25) |

| Do you agree all patients should be tested to identify patients at high risk? | 373 | 261 (70) | 29 (8) | 82 (22) |

| Are you a patient at high risk? | 304 | 56 (18) | 91 (30) | 157 (52) |

| Question . | N . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you know about the different risk groups of patients with CLL? | 377 | 149 (40) | 141 (37) | 87 (23) |

| In the educational courses∗, did you receive any information to help you understand the different risk groups of patients with CLL? | 320 | 84 (26) | 194 (61) | 42 (13) |

| Do you know about any laboratory tests to identify each patient’s risk level? | 312 | 109 (35) | 166 (53) | 37 (12) |

| Do you know about any treatment differences between the different CLL risk groups? | 328 | 86 (26) | 160 (49) | 82 (25) |

| Do you agree all patients should be tested to identify patients at high risk? | 373 | 261 (70) | 29 (8) | 82 (22) |

| Are you a patient at high risk? | 304 | 56 (18) | 91 (30) | 157 (52) |

| . | . | Fixed (%) . | Until progression (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer as a duration of the treatment? | 270 | 185 (69) | 85 (31) |

| . | . | Fixed (%) . | Until progression (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer as a duration of the treatment? | 270 | 185 (69) | 85 (31) |

| . | . | Oral (%) . | Intravenous (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer for administration? | 296 | 232 (78) | 64 (22) |

| . | . | Oral (%) . | Intravenous (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer for administration? | 296 | 232 (78) | 64 (22) |

| . | . | Outpatient (%) . | Inpatient (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer for convenience? | 283 | 257 (91) | 26 (9) |

| . | . | Outpatient (%) . | Inpatient (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you were a patient with CLL at high risk, what would you prefer for convenience? | 283 | 257 (91) | 26 (9) |

| . | . | All patients incl. high-risk (%) . | All patients excl. high-risk (%) . | None (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Should immunochemotherapy still be offered to patients at high risk (or to all patients)? | 357 | 86 (24) | 26 (7) | 22 (6) | 223 (62) |

| . | . | All patients incl. high-risk (%) . | All patients excl. high-risk (%) . | None (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Should immunochemotherapy still be offered to patients at high risk (or to all patients)? | 357 | 86 (24) | 26 (7) | 22 (6) | 223 (62) |

| . | . | Chemoimmunotherapy (%) . | New targeted agents (%) . | No preference (%) . | Discuss with physician first (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What treatment would you like to receive if you were a patient at high risk? (>1 answer permitted) | 350 | 38 (11) | 57 (16) | 170 (49) | 133 (38) |

| . | . | Chemoimmunotherapy (%) . | New targeted agents (%) . | No preference (%) . | Discuss with physician first (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What treatment would you like to receive if you were a patient at high risk? (>1 answer permitted) | 350 | 38 (11) | 57 (16) | 170 (49) | 133 (38) |

Educational course were not defined for survey respondents, and therefore subject to individual interpretation.

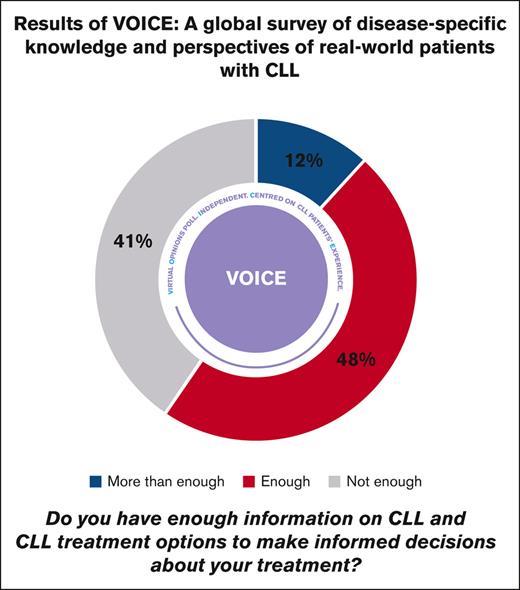

Role of the patient

Regarding the role of patients with CLL in making treatment decisions (Table 2), 41% (145/358) reported they had not received enough information about CLL to make informed treatment decisions. The proportion of respondents who felt they received enough information to make treatment decisions varied by country, ranging from very few in Mexico (4%; 1/28) to all in Slovakia (100%; 29/29; supplemental Figure 1). A large majority of respondents (90%; 336/374) relied on their physicians to answer their questions about CLL and its treatment. Respondents also cited online sources or social media (33%; 124/374) and educational materials or treatment centers (7%; 26/374) as information sources. On a 5-point scale, with 5 representing quite often and 1 not at all, 63% of respondents (210/333) rated the frequency of updates on CLL and its treatment from their physician as 4 or 5.

Role of patients’ in CLL treatment

| Question . | N . | Enough (%) . | More than enough (%) . | Not enough (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have enough information on CLL and CLL treatment options to make informed decisions about your treatment? | 358 | 171 (48) | 42 (12) | 145 (41) |

| Question . | N . | Enough (%) . | More than enough (%) . | Not enough (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have enough information on CLL and CLL treatment options to make informed decisions about your treatment? | 358 | 171 (48) | 42 (12) | 145 (41) |

| . | . | Physician (%) . | Social media/Online (%) . | Treatment center/Educational materials (%) . | Patient associations (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Where do you usually find answers to your questions about CLL and/or CLL treatment? (>1 answer permitted) | 374 | 336 (90) | 124 (33) | 26 (7) | 25 (7) |

| . | . | Physician (%) . | Social media/Online (%) . | Treatment center/Educational materials (%) . | Patient associations (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Where do you usually find answers to your questions about CLL and/or CLL treatment? (>1 answer permitted) | 374 | 336 (90) | 124 (33) | 26 (7) | 25 (7) |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you able to obtain answers to your potential questions concerning CLL or CLL treatment? | 313 | 260 (83) | 53 (17) | N/A |

| Do you want to be heard and participate in treatment decisions during all phases of the CLL treatment? | 368 | 286 (78) | 82 (22) | N/A |

| Do you participate in treatment decisions? | 313 | 138 (44) | 101 (32) | 74 (24) |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Not sure (%) | ||

| Do you know what to expect during follow-up care∗ for CLL? | 291 | 191 (66) | 100 (34) | N/A |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you able to obtain answers to your potential questions concerning CLL or CLL treatment? | 313 | 260 (83) | 53 (17) | N/A |

| Do you want to be heard and participate in treatment decisions during all phases of the CLL treatment? | 368 | 286 (78) | 82 (22) | N/A |

| Do you participate in treatment decisions? | 313 | 138 (44) | 101 (32) | 74 (24) |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Not sure (%) | ||

| Do you know what to expect during follow-up care∗ for CLL? | 291 | 191 (66) | 100 (34) | N/A |

| . | . | Always (%) . | Sometimes (%) . | Not at all (%) . | Unsure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does your physician carefully consider your needs and requests before prescribing the treatment? | 312 | 211 (68) | 68 (22) | 6 (2) | 27 (9) |

| . | . | Always (%) . | Sometimes (%) . | Not at all (%) . | Unsure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does your physician carefully consider your needs and requests before prescribing the treatment? | 312 | 211 (68) | 68 (22) | 6 (2) | 27 (9) |

| . | . | Correctly (%) . | Not correctly (%) . | Neglected (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think mental health issues in patients with CLL are correctly addressed in your country? | 277 | 106 (38) | 111 (40) | 60 (22) |

| . | . | Correctly (%) . | Not correctly (%) . | Neglected (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think mental health issues in patients with CLL are correctly addressed in your country? | 277 | 106 (38) | 111 (40) | 60 (22) |

| . | . | Enough (%) . | Not enough (%) . | Neglected (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you gotten enough support (medical and mental) during the whole treatment duration? | 294 | 178 (61) | 98 (33) | 18 (6) |

| . | . | Enough (%) . | Not enough (%) . | Neglected (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you gotten enough support (medical and mental) during the whole treatment duration? | 294 | 178 (61) | 98 (33) | 18 (6) |

| . | . | 1 (%) . | 2 (%) . | 3 (%) . | 4 (%) . | 5 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you receive regular updates on CLL and its treatment from your physician? Please choose a number from the scale of 1 to 5; where 1 = not at all, and 5 = quite often | 333 | 54 (16) | 25 (8) | 44 (13) | 54 (16) | 156 (47) |

| . | . | 1 (%) . | 2 (%) . | 3 (%) . | 4 (%) . | 5 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you receive regular updates on CLL and its treatment from your physician? Please choose a number from the scale of 1 to 5; where 1 = not at all, and 5 = quite often | 333 | 54 (16) | 25 (8) | 44 (13) | 54 (16) | 156 (47) |

Follow-up care was not defined for survey respondents, and therefore subject to individual interpretation.

Most respondents’ physicians (89%; 279/312) considered their needs and requests always or sometimes before prescribing treatment, and three-fourths of respondents (78%; 286/368) wanted to be involved in treatment decisions. However, a minority participated in their treatment decisions (44%; 138/313).

Almost two-thirds of respondents (62%; 171/277) believed that mental health issues in patients with CLL are not correctly addressed or are neglected, and a substantial number of respondents (39%; 116/294) reported not receiving enough support during treatment, including mental and medical support. The respondents’ answers varied according to country, with >70% of respondents reporting sufficient support in every country with ≥10 respondents except Egypt and Turkey (supplemental Figure 1). One-third of respondents (34%; 100/291) did not know what to expect during follow-up care for CLL.

Impact of COVID-19 on patients

On a 4-point scale, half of respondents (52%; 173/334) reported that COVID-19 had a moderate to high impact on their lives (3 or 4), whereas the rest reported little or no impact (1 or 0). Free text descriptions of what the experience of COVID-19 was like frequently included terms including being scared, experiencing social isolation, lack of psychological support, and stress (supplemental Table 2). Most respondents (79%; 248/312) reported that it was not so difficult or not difficult at all to return to the “new normal” of the postpandemic world, and 70% (256/367) noted that their treatment was not negatively affected by the pandemic (Table 3). Approximately 1 in 5 respondents (19%; 63/331) were unaware that CLL increased their vulnerability to infections.

Impacts of COVID-19

| Question . | N . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affect access to treatment or the continuity of your treatment? | 367 | 111 (30) | 256 (70) |

| Do you know that CLL can leave you vulnerable to infections including COVID-19? | 331 | 268 (81) | 63 (19) |

| Are you able to access COVID-19 vaccination in your country? | 281 | 273 (97) | 8 (3) |

| Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine? | 372 | 344 (92) | 28 (8) |

| Do you know about passive immunization to prevent COVID-19? | 349 | 159 (46) | 190 (54) |

| Question . | N . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affect access to treatment or the continuity of your treatment? | 367 | 111 (30) | 256 (70) |

| Do you know that CLL can leave you vulnerable to infections including COVID-19? | 331 | 268 (81) | 63 (19) |

| Are you able to access COVID-19 vaccination in your country? | 281 | 273 (97) | 8 (3) |

| Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine? | 372 | 344 (92) | 28 (8) |

| Do you know about passive immunization to prevent COVID-19? | 349 | 159 (46) | 190 (54) |

Nearly all respondents (97%; 273/281) reported having access to COVID-19 vaccinations in their country, some were vaccinated against COVID-19 (92%; 344/372), and some received all recommended doses (84%; 299/354). Passive immunization for COVID-19, a process in which antibody-containing blood products are transferred from donors who recovered from infection to patients without immunity, was used early in the pandemic before vaccines and drugs were widely available. However, a majority of patients (54%; 190/349) reported that they were unaware of the importance of passive immunization to prevent COVID-19.

Patients’ knowledge of the side effects of treatments for CLL

Most respondents’ physicians explained the benefits of different treatment options for CLL (84%; 297/355; Table 4), and 90% of respondents (271/301) understood their treatment. Most patients (81%; 300/370) specifically discussed treatment side effects with their physicians always or some of the time; however, 42% (117/277) were actively seeking additional information about the side effects of treatment, primarily from their physician or online sources, including social media.

Knowledge of side effects

| Question . | N . | Yes, always (%) . | Yes, sometimes (%) . | Not at all (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you discussed your side effects with your physician? | 370 | 200 (54) | 100 (27) | 34 (9) | 36 (10) |

| Question . | N . | Yes, always (%) . | Yes, sometimes (%) . | Not at all (%) . | Not sure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you discussed your side effects with your physician? | 370 | 200 (54) | 100 (27) | 34 (9) | 36 (10) |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Unsure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has your physician explained the benefits of different treatment options? | 355 | 297 (84) | 58 (16) | N/A |

| Do you understand the benefits of the treatments you receive? | 301 | 271 (90) | 30 (10) | N/A |

| Are you actively searching for information about your treatments' benefits and side effects? | 277 | 117 (42) | 160 (58) | N/A |

| Do you know which treatment side effects are short-term, which are long-term, and the differences between them? | 298 | 81 (27) | 85 (29) | 132 (44) |

| Are you equally concerned about the short- and long-term treatment side effects? | 273 | 188 (69) | 83 (30) | N/A |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Unsure (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has your physician explained the benefits of different treatment options? | 355 | 297 (84) | 58 (16) | N/A |

| Do you understand the benefits of the treatments you receive? | 301 | 271 (90) | 30 (10) | N/A |

| Are you actively searching for information about your treatments' benefits and side effects? | 277 | 117 (42) | 160 (58) | N/A |

| Do you know which treatment side effects are short-term, which are long-term, and the differences between them? | 298 | 81 (27) | 85 (29) | 132 (44) |

| Are you equally concerned about the short- and long-term treatment side effects? | 273 | 188 (69) | 83 (30) | N/A |

| . | . | Enough (%) . | To some extent (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you received enough information about the side effects of your treatment from your physician? | 295 | 155 (53) | 106 (36) | 34 (12) |

| . | . | Enough (%) . | To some extent (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you received enough information about the side effects of your treatment from your physician? | 295 | 155 (53) | 106 (36) | 34 (12) |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | To some extent (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you gotten enough information about the possible side effects and potential health problems of the CLL treatments in your educational courses? | 271 | 53 (20) | 65 (24) | 153 (57) |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | To some extent (%) . | No (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you gotten enough information about the possible side effects and potential health problems of the CLL treatments in your educational courses? | 271 | 53 (20) | 65 (24) | 153 (57) |

Two-thirds of respondents (69%; 188/273) indicated they were equally concerned about short- and long-term side effects. More than 25% of respondents reported moderate or high impact of their CLL treatments’ side effects in the physical, psychological, social, emotional, and work-related domains, including more than one-third of respondents for physical and psychological impacts (supplemental Figure 2).

Overall, half of the respondents (53% 155/295) received enough information from their physicians about the side effects of their treatments. Answers varied by country, and only Egypt (79%) and Turkey (61%) had majorities of respondents who did not receive enough information. Overall, 1 in 5 respondents (20%; 53/271) reported getting enough information on treatment side effects from their educational courses.

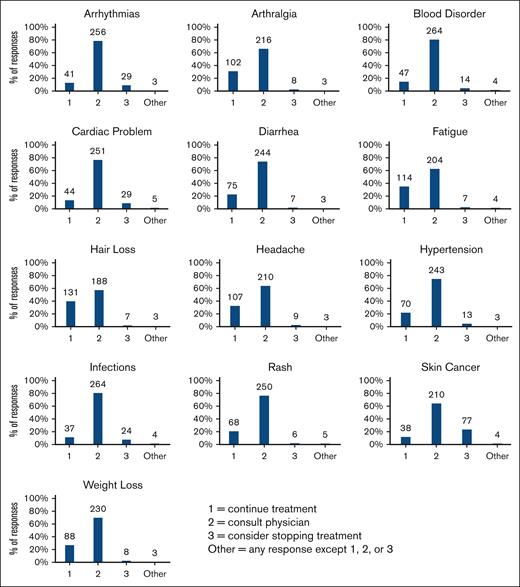

Patients’ reasons for stopping treatment

Most respondents (86%; 288/333) first contacted a medical oncologist-hematologist for treatment-related health issues (Table 5). As shown in Figure 1, over 1 in 5 patients (21%-40%) would continue treatment for side effects including hypertension, headache, arthralgia, fatigue, diarrhea, rash, weight loss, and hair loss, whereas 11% of patients would continue treatment in the event of an infection. The survey did not specify whether stopping treatment included temporary interruptions of treatment and/or permanent treatment discontinuation. Notably, 23% of respondents would consider stopping treatment if skin cancer developed, the highest rate for any side effect queried. Geographical distributions for several important side effects are shown in supplemental Figure 3.

Reasons for stopping CLL treatment

| . | N . | Nurse (%) . | General practitioner (%) . | Medical oncologist-hematologist (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who do you contact first if you have any health issues before or during treatment? | 333 | 21 (6) | 24 (7) | 288 (86) |

| . | N . | Nurse (%) . | General practitioner (%) . | Medical oncologist-hematologist (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who do you contact first if you have any health issues before or during treatment? | 333 | 21 (6) | 24 (7) | 288 (86) |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Unsure (%) . | Other (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If you are prescribed any of the following therapies, do you know about any side effects connected to your therapies? | 219 | 69 (32) | 66 (30) | 84 (38) | N/A |

| If you have any unbearable side effects during treatment, would you consider stopping your treatment for CLL? | 363 | 119 (33) | 75 (21) | 169 (47) | N/A |

| If you stopped treatment because of side effects, do you believe control of your CLL suffered? | 250 | 84 (34) | 45 (18) | 88 (35) | 32 (13) |

| Would you be worried about telling your physician about treatment side effects because/he might stop your treatment? | 307 | 21 (7) | 243 (79) | 43 (14) | N/A |

| . | . | Yes (%) . | No (%) . | Unsure (%) . | Other (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If you are prescribed any of the following therapies, do you know about any side effects connected to your therapies? | 219 | 69 (32) | 66 (30) | 84 (38) | N/A |

| If you have any unbearable side effects during treatment, would you consider stopping your treatment for CLL? | 363 | 119 (33) | 75 (21) | 169 (47) | N/A |

| If you stopped treatment because of side effects, do you believe control of your CLL suffered? | 250 | 84 (34) | 45 (18) | 88 (35) | 32 (13) |

| Would you be worried about telling your physician about treatment side effects because/he might stop your treatment? | 307 | 21 (7) | 243 (79) | 43 (14) | N/A |

N/A, not applicable.

Patients’ responses to new side effects. Respondents (N = 329) indicated which of the 3 actions they would take if they noticed a new side effect they thought was caused by their CLL treatment. The answer options were (1) continue treatment as usual; (2) consult their physician about the side effect; or (3) consider stopping treatment. All responses besides the numerals 1, 2, or 3 were reported as “other.”

Patients’ responses to new side effects. Respondents (N = 329) indicated which of the 3 actions they would take if they noticed a new side effect they thought was caused by their CLL treatment. The answer options were (1) continue treatment as usual; (2) consult their physician about the side effect; or (3) consider stopping treatment. All responses besides the numerals 1, 2, or 3 were reported as “other.”

Unbearable side effects would cause one-third of respondents (33%; 119/363) to stop their treatment, and 13% (44/337) previously experienced intolerable side effects. Half of respondents (50%; 143/286) received information concerning the impacts of stopping treatment, which is typically discussed when side effects occur, and discontinuation is considered. Among those who stopped treatment, a minority (18%; 45/250) of respondents reported that they were sure that the control of their CLL had not suffered. Notably, a majority of respondents (79%; 243/307) were not worried about discussing side effects with their clinicians for fear of having their treatment stopped.

Finally, respondents were asked if they would stop treatment for any of several reasons using a 4-point scale from 1 (no impact) through 4 (high impact), as shown in Figure 2. The highest proportion of “high impact” responses (option 4) were observed for treatment unavailability (52%; 186/356), no clinical improvement (39%; 139), and financial issues (33%; 119). The decision to stop treatment was least affected (option 1) by factors, including feeling better and not wanting to continue treatment (47%; 167), not wanting to take daily medication (54%; 193), and lack of emotional support (54%; 192). A small number of patients (20%; 70) reported that experiencing side effects had a high impact on the decision to stop treatment.

Reasons for stopping treatment. Respondents (N = 356) indicated how impactful each factor would be to their decision to stop treatment. The answer options were (1) no impact; (2) little impact; (3) moderate impact; or (4) high impact. All responses besides the numerals 1, 2, 3, or 4 were reported as “other.”

Reasons for stopping treatment. Respondents (N = 356) indicated how impactful each factor would be to their decision to stop treatment. The answer options were (1) no impact; (2) little impact; (3) moderate impact; or (4) high impact. All responses besides the numerals 1, 2, 3, or 4 were reported as “other.”

Discussion

This study was designed and conducted to explore the knowledge and perspectives of patients will CLL from around the world. Questions covered topics to assess patients’ awareness of risk groups, their role in treatment decisions, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care, their knowledge and attitudes about the side effects of treatments for CLL, and reasons for stopping treatment, topics for which there is little published evidence. The methods used to recruit survey respondents via treating physicians, PAGs, and social media channels targeted patients most likely to be knowledgeable about CLL and actively engaged in their treatment. As a result, the gaps in patient knowledge and care observed in this study are likely to underestimate the unmet needs of most patients.

Most respondents did not understand the different risk groups in CLL, and most did not receive relevant information in their educational courses, indicating that improved patient education is needed. Despite the lack of knowledge surrounding risk groups, most respondents favored risk group testing. If they were at high risk, most patients preferred the convenience of fixed duration treatments, oral administration, and outpatient settings.

Most respondents received enough information to make informed treatment decisions, and their primary source for reliable information was their physician. This shows that the physician-patient relationship in CLL care continues to be important, despite the abundance of information from many sources on the Internet, both reliable and unreliable. Indeed, many of the respondents sought additional information related to CLL online and from social media, but most still counted primarily on their physician, which is consistent with the authors’ experiences from other surveys conducted by PAGs. Although it is understandable that patients turn to online sources for information, the abundance of unreliable or inaccurate information is a concern. Thus, digital tools to guide patients’ to sources that are vetted and reliable would be beneficial. Educational materials and PAGs were sources of information for few respondents, suggesting that these sources are not currently meeting patient’s educational needs, and their effectiveness should be re-evaluated.

The proportion of respondents who wanted to participate in therapeutic decision-making was nearly double the proportion who actually participated in their care (78% vs 44%), suggesting that clinicians should involve patients more in treatment decisions. This also requires better patient education about risk groups.

Most respondents thought that mental health issues were incorrectly addressed or neglected in their country, indicating an unmet need for mental health care among patients with CLL. One potential solution is developing platforms that allow PAGs to provide mental support to patients by facilitating the meeting of patients and mental health specialists. In our experience, mental health support from PAGs can be beneficial, and several such endeavors have been developed with physicians and psychologists including consultations with psycho-oncologists, individual and group psychotherapy sessions, informational materials, and webinars (supplemental Data 1). Effectiveness of such efforts could be improved with greater emphasis on the areas in which we found gaps in patients’ knowledge. However, such services require patients to self-identify with a need, so screening and referral processes must be in place so more patients can fully use them. Patients’ mental health should also be addressed by raising awareness of mental health issues with physicians who treat patients with CLL, who are trusted by patients and can assess their mental health at the time of diagnosis and treatment initiation. All authors from both PAGs and clinical sides agreed that psychological support is very important, but lack of resources is often a problem.

Access to health care was not negatively affected for most patients because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and most were also able to receive COVID-19 vaccinations. Primary prevention of COVID-19, and all infections, is a priority in CLL care. Accordingly, CLL experts have universally recommended social distancing, and 68% advocated stronger measures, including wearing N-95 masks and gloves when patients go out of their homes.29 However, ∼20% of our surveys’ respondents did not understand that CLL makes them more vulnerable to infections, which is concerning. PAGs have an important role to play in disseminating this information. Governments also provide this information via telephone hotlines, websites, or treatment centers, but these are often difficult for patients to access or understand. In some countries, there is no direct channel for patients to ask and receive answers from governmental sources, and PAGs could fill these gaps by providing accessible information that helps patients understand their vulnerability to infections and how to protect themselves. In addition, the lack of awareness about passive immunization shows a need to educate patients about alternative methods of COVID-19 prevention available, although this method in particular is no longer effective.30

The physical and psychological impacts of CLL treatment side effects were rated highest by respondents, but substantial numbers of respondents cited high impacts in social, emotional, and work domains as well. Although two-thirds to three-quarters of respondents would consult their physicians if they experienced certain side effects, the proportion of respondents who would continue treatment despite cardiovascular side effects (hypertension, cardiac problems, and arrythmias) is concerning, because these constitute potentially severe side effects of CLL treatment. The same was true concerning rash and diarrhea, with many patients determined to continue treatment instead of consulting their physician, even though these symptoms could be a sign of infection. Conversely, over 20% of respondents would stop their treatment if they developed skin cancer, losing the benefit of treatment even though this side effect could be managed. Some of this may be due to the additional time and effort required to treat skin cancer in addition to CLL, but it may also reflect the degree of gravity patients associate with cancer. As such, these results show a gap in education about the seriousness of certain side effects. Interestingly, 40% of respondents from Turkey and 60% in Slovakia would stop treatment if they developed skin cancer, nearly double the rate overall.

Overall, the results concerning side effects showed that the respondents would be reluctant to stop treatment, only one-third would stop for unbearable side effects, but they also showed that respondents were not worried about being forced to stop treatment and were willing to report their side effects to their physician. This again demonstrates the strength of the physician-patient relationship in these patients. Respondents understandably reported that factors, such as treatment unavailability, financial issues, or lack of clinical progress would have a high impact on patients’ decisions to stop treatment.

Finally, some of the responses in this survey represent the first data on patient perspectives from countries outside of North America and Europe, and some results suggest region-specific gaps. The notably low proportion of patients from Mexico who received enough information to make treatment decisions (4%) lags far behind the other countries in the survey, and a higher proportion of Egyptian patients reported insufficient medical and mental support during treatment (70%). Overall, the geographic distribution of results shows a marked heterogeneity in the provision of medical information and support in different countries around the world. However, although this survey serves to highlight those areas where additional education and information are required, it is not designed to determine the reasons for these differences, which will require further investigation.

The interpretation of this survey’s results is limited by several factors. The study population is not randomly selected or representative because participation was voluntary, and demographic information was not collected. Because this is an anonymous survey, respondents’ current stage of disease, treatment history, and demographic information are unavailable. Respondents were not required to answer every question to encourage participation from patients who found the length of the survey challenging, therefore some items have a larger sample size than others. Lastly, the survey was retrospective in nature and was subject to recall bias.

Nevertheless, this survey contributes valuable and unprecedented data on perspectives and unmet needs of patients with CLL at a global scale, including substantial proportions of patients from countries outside of Europe and the United States, regarding their condition and multiple aspects of their treatment.12,13,15,29 The results show several knowledge gaps, including familiarity with risk groups, patients’ increased susceptibility to COVID-19 and common side effects of treatment but also indicate possible ways to address these gaps. Patients with CLL have trust in their treating physicians and a willingness to communicate with them, so physicians are well-positioned as a trusted source to deliver information to patients. The number of patients who reported wanting to be involved in their treatment but were not, also suggests patients need to be encouraged to be more proactive in discussing their options with their physicians. These results can help target patient educational initiatives by clinicians, PAGs, and policy makers. The first such initiative based on the global gaps identified in this study is an online portal currently under development for use by PAGs. This portal will provide PAGs with educational materials that can be adapted and used to reduce these gaps via targeted patient education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erik MacLaren, a medical writer funded by MphaR, for writing and editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication. AstraZeneca provided funding for this project but had no role in manuscript development, review, approval, or in the decisions regarding the submission of this manuscript for publication.

Authorship

Contribution: C.T. was responsible for chairing the author panel and drafting the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the design of the survey, analyzed the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement: C.T. received support from BeiGene for the preparation of this manuscript. In addition, his institution receives research funding from Janssen and AbbVie, and he has received honoraria from BeiGene, Janssen, and AbbVie. J.P.-I. has received consulting fees from Novartis, Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), and Merck. He has also received consulting and speakers’ bureau fees from Janssen/Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, BeiGene, and Takeda. A.C.F. has received speakers’ bureau fees from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, and Janssen, and she has participated in advisory boards for AstraZeneca and AbbVie. In addition, she has received travel support for the European Hematology Association Congress and a preceptorship. K.H. has indirectly received support via institutional grants, contracts, and consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, and Roche. M.A.M. has received payments for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AbbVie, Janssen, and AstraZeneca. M.P. has received payment or honoraria from, and participated in advisory boards for Janssen, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie. He has also received travel support from Roche and Raffo. F.P.’s institution (Asociación Leucemia Mieloide de Argentina) receives grants from Janssen-Cilag Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Pint-Pharma, Varifarma, and Pfizer. M.S. has received travel support from, and participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Janssen-Cilag. He also owns stock or stock options in AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Merck, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, and Novartis. S.S. has received consulting fees, research funding, speakers bureau payments, and honoraria from and participated in advisory boards for AbbVie, Acerta, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, Incyte, Infinity, Janssen, Novartis, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis, and Verastem. C.G.C., V.K., M.M., C.M. declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Constantine Tam, Alfred Hospital and Monash University, Commercial Rd, East Melbourne 3004, Australia; e-mail: constantine.tam@alfred.org.au.

References

Author notes

A copy of the full survey results can be obtained on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Constantine Tam (constantine.tam@alfred.org.au).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement