TO THE EDITOR:

Data on outcome of CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy for patients with large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) with secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement (SCNSL) are limited. In this study, we present results of CD19 CAR-T therapy for relapsed/refractory SCNSL in a German multicenter real-world cohort, a collaborative effort of the German Lymphoma Allianz (GLA) and the German Stem Cell Transplant Registry (DRST). Data collection and analysis were in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was available for all patients, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Tübingen.1 Data collection and overall outcomes of the total cohort of patients with LBCL have been described previously.1 Four patients from the SCNSL cohort have also been separately reported before.2 In total, 28 patients with and 168 patients without SCNSL were identified in 9 of the initial 21 centers.1 CNS involvement was diagnosed through imaging, cytology, and flow cytometry for leptomeningeal and histology for parenchymal manifestations.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. SCNSL was the sole manifestation in 9 patients (32%), whereas 19 patients (68%) also had other (systemic) manifestations.

Patient and treatment characteristics

| Characteristic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| No CNS involvement | 168 |

| CNS involvement | 28 |

| Histology | |

| DLBCL | 158 (81) |

| tFL | 17 (9) |

| PMBCL | 11 (6) |

| tMZL | 3 (1.5) |

| tCLL | 3 (1.5) |

| tHL | 2 (1) |

| Richter transformation | 1 (<1) |

| Burkitt | 1 (<1) |

| Only patients with CNS involvement | |

| Type of involvement | |

| Parenchymal involvement only | 16 (57) |

| Meningeal involvement only | 6 (21) |

| Parenchymal and meningeal involvement | 6 (21) |

| CAR T-cell product | |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | 14 (50) |

| Tisagenlecleucel | 14 (50) |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 58 (33-79) y |

| Sex | |

| Male | 16 (57) |

| Female | 12 (43) |

| International Prognostic Index | |

| Median (range) | 3 (1-5) |

| Normal LDH at CAR-T | 13 (48) |

| Bridging | |

| No | 4 (14) |

| Yes | 24 (86) |

| Intrathecal therapy | 4 (14) |

| CNS irradiation | 3 (11) |

| Polatuzumab based | 5 (18) |

| Venetoclax/ibrutinib | 4 (14) |

| Gemcitabine-oxaliplatin | 2 (7) |

| Others | 6 (25) |

| Response to bridging | 10 (42) |

| Characteristic . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| No CNS involvement | 168 |

| CNS involvement | 28 |

| Histology | |

| DLBCL | 158 (81) |

| tFL | 17 (9) |

| PMBCL | 11 (6) |

| tMZL | 3 (1.5) |

| tCLL | 3 (1.5) |

| tHL | 2 (1) |

| Richter transformation | 1 (<1) |

| Burkitt | 1 (<1) |

| Only patients with CNS involvement | |

| Type of involvement | |

| Parenchymal involvement only | 16 (57) |

| Meningeal involvement only | 6 (21) |

| Parenchymal and meningeal involvement | 6 (21) |

| CAR T-cell product | |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | 14 (50) |

| Tisagenlecleucel | 14 (50) |

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 58 (33-79) y |

| Sex | |

| Male | 16 (57) |

| Female | 12 (43) |

| International Prognostic Index | |

| Median (range) | 3 (1-5) |

| Normal LDH at CAR-T | 13 (48) |

| Bridging | |

| No | 4 (14) |

| Yes | 24 (86) |

| Intrathecal therapy | 4 (14) |

| CNS irradiation | 3 (11) |

| Polatuzumab based | 5 (18) |

| Venetoclax/ibrutinib | 4 (14) |

| Gemcitabine-oxaliplatin | 2 (7) |

| Others | 6 (25) |

| Response to bridging | 10 (42) |

DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PMBCL, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma; tCLL, transformed chronic lymphocytic leukemia; tFL, transformed follicular lymphoma; tHL, transformed hodgkin lymphoma; tMZL, transformed marginal zone lymphoma.

To enable a more representative comparison, a matched-pair analysis of patients with and without CNS involvement was performed (adjusted for age, sex, performance status, and International Prognostic Index as matching factors). Matched cohorts were created using a greedy caliper algorithm.3 Further details of statistical methods are presented in supplemental Material. The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS), defined as absence of relapse/progression or death from any cause. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) were graded according to previously published consensus guidelines.4,5

In total, there were 28 patients with SCNSL, 24 of whom received bridging therapy and 10 of 24 (42%) had clinical or partial response of CNS lymphoma after bridging therapy; no complete remission was documented. Three of 4 patients (75%) responded to intrathecal therapy, 2 of 3 (67%) to CNS irradiation, 1 of 5 to polatuzumab (20%), 1 of 2 to gemcitabine-oxaliplatin (50%), 1 of 4 to venetoclax + ibrutinib (25%), and 2 of 6 (33%) and 1 each (100%) to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone and high-dose methotrexate-based immuno-chemotherapy for elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients protocol.

The median follow-up of patients with SCNSL from the time of CAR-T infusion was 17 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 10-25). Best response (which may also include effect of bridging therapy) was a complete response in 9 (32%), partial response in 9 (32%), progressive disease in 7 (25%), and stable disease in 3 (11%) patients. Median overall survival was 21 months and median PFS was 3.8 months (95% CI, 0.01-9.4). Twelve-month PFS was 41% (95% CI, 22-60), 12-month overall survival was 63% (95% CI, 44-80). The 12-month PFS for axicabtagen-ciloleucel (axi-cel) vs tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel) in patients with CNS involvement was 62% (95% CI, 36-88) vs 19% (95% CI, 0-32).

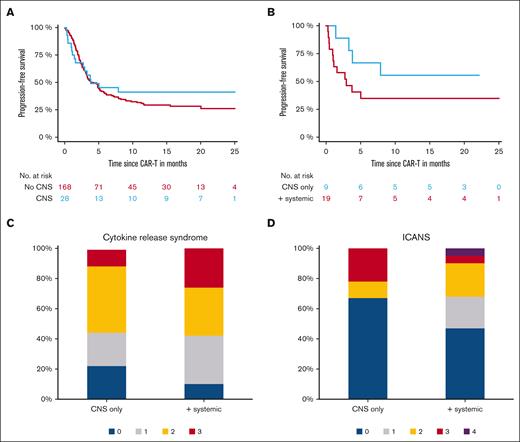

Next, we compared the outcome of the 28 patients with SCNSL with that of 168 consecutive, contemporary patients without CNS involvement. Twelve-month PFS was 41% (95% CI, 22-60) vs 29% (95% CI, 12-46) for patients with CNS vs no CNS manifestation (P = .47; Figure 1A). Results were confirmed in the matched comparison of 28 patients vs 28 matched patients without CNS involvement (P = .61; supplemental Data; supplemental Figure). According to CAR-T product, 12-month PFS was 62% for patients with CNS involvement vs 36% for patients without CNS involvement who received axi-cel (P = .16) and 19% vs 32% for patients who received tisa-cel (P = .44).

Outcomes after CAR-T infusion for patients with CNS manifestation. (A) Graph shows PFS for patients with CNS manifestations vs patients without CNS manifestation. (B) Graph shows PFS according to CNS only and CNS in addition to systemic involvement. (C-D) Plots show incidence of CRS and ICANS for CNS only and CNS in addition to systemic involvement.

Outcomes after CAR-T infusion for patients with CNS manifestation. (A) Graph shows PFS for patients with CNS manifestations vs patients without CNS manifestation. (B) Graph shows PFS according to CNS only and CNS in addition to systemic involvement. (C-D) Plots show incidence of CRS and ICANS for CNS only and CNS in addition to systemic involvement.

We next compared outcome of patients with CNS involvement alone (n = 9) vs CNS and other (systemic) manifestations (n = 19); 12-month PFS was 56% (95% CI, 24-88) vs 35% (95% CI, 13-57; P = .16), respectively (Figure 1B).

In multivariate analysis of the total 9-center cohort (n = 196) including CNS involvement as variable, lactate dehydrogenase >2× upper limit was associated with shorter PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 1.98; P = .003), response to bridging therapy was associated with longer PFS (HR, 0.49; P = .03), in line with the previously published findings of the 21-center cohort. Notably, CNS involvement did not affect PFS (HR, 0.63; P = .22) (supplemental Table 1).

Three events of nonrelapse mortality occurred in the SCNSL cohort, all owing to bloodstream infections on day 10, 13, and 27 after CAR-T infusion. Nonrelapse mortality at 12 months for the total cohort of 168 patients without and 28 with CNS involvement was 7% (95% CI, 5-9) vs 11% (95% CI, 5-16; P = .34). CRS of any grade could be observed in 24 patients (86%) and grade 3 could be observed in 6 patients (21%); none of the patients had grade 4 CRS. ICANS occurred in 13 patients (46%), grade 3 in 3 patients (11%), and grade 4 in 1 patient (4%). Median time to ICANS was 5 days (range, 3-15 days) after CAR-T infusion. No significant difference in the incidence and severity of CRS and ICANS were seen between tisa-cel and axi-cel (P = .71 and .81, respectively); frequencies are presented in supplemental Material. There was neither a significant association between CRS nor between ICANS with response to CAR-T therapy (P = .89 and .62, respectively).

For the comparison of CNS only vs CNS and systemic involvement, significant difference in incidence and severity in neither CRS nor ICANS was observed (P = .63 and .31, respectively; Figure 1C-D). In the matched comparison of 28 patients vs 28 patients without CNS involvement, no difference was seen for incidence of CRS or ICANS (P = .32 and .71, respectively). Outcomes are in presented in the supplemental Material.

In this multicenter cohort study, we found that CD19 CAR-T therapy for patients with LBCL with SCNSL is safe, feasible, and results in efficacy and durable responses comparable to outcome in those without CNS involvement.

The ZUMA-1 and JULIET trials, which led to the approval of CAR-T therapy for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, excluded patients with CNS involvement partly because of concerns regarding increased risk of ICANS.6,7 Of six evaluable patients with secondary CNS lymphoma in TRANSCEND, 3 (50%) achieved a complete remission, no patients had severe CRS, and 2 (33%) patients had grade 3 ICANS.8 Several case studies have reported the efficacy and manageable adverse events of CAR-T therapy in primary and SCNSL, however in small, mostly single center cohorts and with short follow-up.9-14 Duration of remission of SCNSL after CD19 CAR-T therapy has also been suggested to be shorter than that for patients without CNS involvement,11 highlighting the need for longer follow-up.

Our outcomes are consistent with previously published results and add stronger evidence with longer follow-up and a matched comparison, highlighting comparable outcomes of patients with and without CNS involvement. Accumulating real-world data indicate better efficacy but higher incidence and severity of ICANS of axi-cel than that of tisa-cel but without detailed analysis of patients with SCNSL.1,15 A recent meta-analysis including 128 patients reported safety and efficacy of CAR-T in secondary (n = 98) and primary (n = 30) CNS lymphoma similar to outcomes for patients without CNS involvement.16 We report excellent outcome for patients with SCNSL treated with axi-cel. Notably, incidence and severity of ICANS did not differ between the axi-cel and tisa-cel groups.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature and relatively small sample size, but it underscores 2 major findings. First, SCNSL involvement should not preclude patients from receiving CD19 CAR-T therapy as a potentially curative treatment option because of concerns regarding ICANS or overall worse outcomes. Second, axi-cel shows excellent efficacy in SCNSL without increase in incidence or severity of ICANS.

In conclusion, our long-term safety and efficacy analyses support the use of CAR-T therapy in patients with SCNSL.

Contribution: F.A., W.B., and P.D. designed the study; F.A. and N.G. analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; F.A., B.v.T., G.W., K.R., M.S., O.P., C.D.B., N.K., W.B., and P.D. collected and provided patient data; and all authors read, commented on, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: F.A. received honoraria from Novartis, Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Janssen, Takeda, Medac, and Therakos/Mallinckrodt, and received research funding from Therakos/Mallinckrodt. B.v.T. is an adviser or consultant for Allogene, BMS/Celgene, Cerus, Incyte, IQVIA, Gilead Kite, Miltenyi, Novartis, Noscendo, Pentixapharm, Roche, Amgen, Pfizer, Takeda, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), and Gilead Kite; has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, BMS, Incyte, Novartis, Roche Pharma AG, Takeda, and MSD; reports research funding from Novartis (institutional), MSD (institutional), and Takeda (institutional); and reports travel support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Gilead Kite, MSD, Roche, Takeda, and Novartis. G.W. received honoraria from Gilead, Novartis, Takeda, Clinigen, and Amgen. K.R. received research funding and travel support from Kite/Gilead; honoraria from Novartis; and consultancy and honoraria from BMS/Celgene. M.S. received honoraria from Kite/Gilead, Jazz, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and BMS/Celgene. O.P. received honoraria or travel support from Astellas, Gilead, Jazz, MSD, Neovii Biotech, Novartis, Pfizer, and Therakos; received research support from Gilead, Incyte, Jazz, Neovii Biotech, and Takeda; and is on advisory boards of Jazz, Gilead, MSD, Omeros, Priothera, Shionogi, and Sobi. C.D.B. received honoraria and travel funds from BMS, Amgen, Novartis, Jazz, Gilead, and Janssen. N.K. received honoraria from Kite/Gilead, Jazz, MSD, Neovii Biotech, Novartis, Riemser, Pfizer, and BMS, received research support from Neovii, Riemser, Novartis, and BMS. W.B. received honoraria and travel funds from Gilead, Novartis, Miltenyi, and Janssen, and research grants from Miltenyi. P.D. received consultancy from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, bluebird bio, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Riemser, and Roche; speaker’s bureau fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Gilead, Novartis, Riemser, and Roche; and research support from Riemser. N.G. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Francis Ayuk, Department of Stem Cell Transplantation, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistr 52, 20246 Hamburg, Germany; e-mail: ayuketang@uke.de.

References

Author notes

∗F.A. and N.G. contributed equally to this study.

†W.B. and P.D. contributed equally to this study.

Presented in abstract form at the 64th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in New Orleans, LA, 10-13 December 2022.

Deidentified individual participant data will only be shared upon request and approval of treating center from the corresponding author, Francis Ayuk (ayuketang@uke.de).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.