Key Points

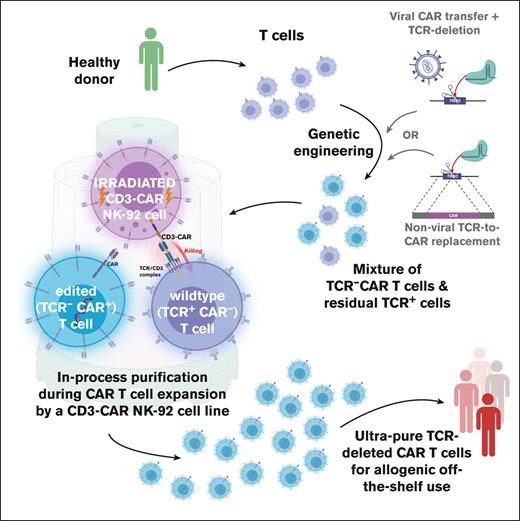

Addition of short-lived TCR-specific CAR NK-92 cells allows efficient depletion of TCR+ cells during expansion of TCR-edited CAR T cells.

NK cell–mediated purification increases the purity and yield of TCR-deleted CAR T cells without affecting their effector function.

Abstract

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a major risk of the administration of allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-redirected T cells to patients who are HLA unmatched. Gene editing can be used to disrupt potentially alloreactive T-cell receptors (TCRs) in CAR T cells and reduce the risk of GVHD. Despite the high knockout rates achieved with the optimized methods, a subsequent purification step is necessary to obtain a safe allogeneic product. To date, magnetic cell separation (MACS) has been the gold standard for purifying TCRα/β– CAR T cells, but product purity can still be insufficient to prevent GVHD. We developed a novel and highly efficient approach to eliminate residual TCR/CD3+ T cells after TCRα constant (TRAC) gene editing by adding a genetically modified CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell line during ex vivo expansion. Two consecutive cocultures with irradiated, short-lived, CAR NK-92 cells allowed for the production of TCR– CAR T cells with <0.01% TCR+ T cells, marking a 45-fold reduction of TCR+ cells compared with MACS purification. Through an NK-92 cell–mediated feeder effect and circumventing MACS-associated cell loss, our approach increased the total TCR– CAR T-cell yield approximately threefold while retaining cytotoxic activity and a favorable T-cell phenotype. Scaling in a semiclosed G-Rex bioreactor device provides a proof-of-principle for large-batch manufacturing, allowing for an improved cost-per-dose ratio. Overall, this cell-mediated purification method has the potential to advance the production process of safe off-the-shelf CAR T cells for clinical applications.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have emerged as a potent therapy for hematological malignancies. By September 2022, 6 CAR T products have been approved in the United States. Although all approved products are based on patient-derived T cells, there is growing interest in the development of allogeneic CAR T cells. Large-scale manufacturing of allogeneic off-the-shelf CAR T-cell products would be a way to reduce the cost and avoid the logistics associated with autologous cell manufacturing.1 However, graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) remains an critical risk when administering allogeneic CAR T-cell products to patients.2

Gene-editing tools can be used to reduce the risk of GVHD by eliminating the alloreactive T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex via the knockout (KO) of 1 of its components,3-5 usually the TCRα constant (TRAC) gene.3 Different gene-editing systems, such as CRISPR-Cas or transcriptional activator-like effector nucleases, can be used to disrupt TRAC expression.6 Furthermore, targeted in-frame insertion of CAR transgenes into an early exon of TRAC can be used to functionally replace endogenous TCR with tumor-specific CARs.7-10 Despite the high KO rate achieved via gene-editing tools, conventional manufacturing strategies still use a further purification step before the final formulation and/or cryopreservation of the allogeneic CAR T-cell product to ensure safety.11-13

Previous clinical trials with patients undergoing haploidentical stem cell transplantation estimated the threshold for the occurrence of GVHD to be ∼5 × 104 TCRα/β T cells/kg body weight.14,15 This translates to a relative threshold of no more than 1.0% TCRα/β T cells within the final allogeneic CAR T-cell product when applied at a relatively low dose of 1 × 106 CAR+ cells/kg body weight, given an exemplary CAR+ rate of 20% (supplemental Table 1). Clinical case reports using unmatched allogeneic CAR T cells demonstrated that as little as 1% to 2% contaminating TCRα/β+ T cells in gene-edited cell products can induce GVHD in patients with heavily pretreated leukemia.11 Although the reported symptoms were manageable with steroid treatment, this indicates an imperative need to develop enhanced enrichment strategies for higher product purity to prevent GVHD, especially at high CAR T-cell doses required for effective treatment16 or with repetitive dosing.17

The predominant method for purifying allogeneic TCR-deleted CAR T cells is magnetic cell separation (MACS). However, significant cell loss and postseparation impurities ranging from 0.1% to 1.1% in clinical products limit their usage.11,12,18 Jullierat et al demonstrated that transfection of a CD3-specific CAR messenger RNA 2 days after TRAC editing enables the enrichment of TCR–T cells during expansion, resulting in residual contamination of ∼0.1% to 2% TCRα/β+ cells.19 Being an in-process purification method, this alleviates reagent-intensive cell handling and the cell loss associated with magnetic TCR depletion at the end of CAR T-cell expansion.

Irradiated natural killer cell (NK)-derived NK-92 cell lines have been tested in patients,20 rendering them as a promising candidate for a cell-mediated purification approach. Herein, we engineered an NK-92 cell line to express a CD3-specific CAR. We compared 4 different CD3-/TCR-specific CARs to create an NK-92 cell line that effectively purifies TCR– (CAR) T cells from residual TCR+ T cells when added during ex vivo expansion. To identify the parameters for the effective purification of TCR-edited T cells, optimization of the NK-92 cell dose as well as of the coculture timing were performed. As proof-of-principle, optimized conditions were used to generate gene-edited, TRAC-replaced CAR T cells. Subsequently, CAR T-cell products were characterized for their phenotype and in vitro function. We showed that the addition of short-lived, irradiated CD3-CAR NK-92 allows for the dynamic TCR/CD3 elimination throughout the CAR T-cell expansion period, resulting in the effective removal of TCR/CD3+ cells without affecting the functional profile of CAR T cells.

Materials and methods

Ethic statement and cell sources

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Charité ethics committee approval EA4/091/19). Peripheral blood from healthy human adults was obtained after obtaining informed consent. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated via density-gradient centrifugation using BioColl (Bio&SELL). T cells were enriched from peripheral blood mononuclear cells via MACS using CD3 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Frozen aliquots of NK-92 and NALM-6 cell lines were obtained from Leibniz Institute, DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms, and Cell Cultures GmbH.

Cell culture

The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco), containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma Aldrich). The medium was supplemented with recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2; 500 IU/mL; Miltenyi) for NK-92 cells, and IL-2 (200 IU/mL), IL-7 (10 ng/mL; CellGenix), and IL-15 (5 ng/mL; CellGenix) for primary T cells. T cells were activated for 48 hours using αCD3/28 antibody-coated polystyrene tissue culture plates (Corning Inc).10

Generation of TCR/CD3-CAR double stranded DNA templates for gene editing

All TCR/CD3-CAR DNA sequences are shown in supplemental Table 2. Generation of double stranded DNA–homology-dependent DNA Repair (HDR) templates was performed as described.10 They consisted of a CAR expression cassette flanked by 400 bp long sequences homologous to the AAVS1 locus. The CAR transgene itself encodes a myc-tagged antibody-derived single chain variable fragment (scFv) fused either to a CD28.CD3ζ or a CD8a.4-1BB.CD3ζ CAR stalk. HDR templates from sequence-verified plasmid DNA were amplified via polymerase chain reaction, purified with paramagnetic beads (Ampure XP, Beckman Coulter), and adjusted to 1000 ng/μL.

Nonviral CAR transfer to primary human T cells

Virus-free CAR transfer to primary human T cells was performed as previously described.10 In brief, TRAC-targeting synthetic modified single guide RNA (100 μM; IDT) was mixed with an aqueous solution of ∼15 to 50 kDa poly(L-glutamic acid) (100 μg/μL; Sigma Aldrich)21 and recombinant SpCas9 protein (61 μM; IDT) in a 0.96:1:0.8 volume ratio to form precomplexed ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). Two days after isolation, activated T cells were resuspended in TheraPEAK P3 Primary Cell Nucleofector Solution (Lonza; 5-10 × 106 cells per 100 μL) and mixed with RNP (10.35 μL per 100 μL suspension) and CD19.CD28.CD3ζ-CAR10 (Addgene; Plasmid #183473) double stranded DNA–HDR template (2.5 μl/100 μL suspension). The suspension was electroporated (in 20 μL or 100 μL electroporation vessels) in a Lonza 4D nucleofector device using the program EH-115.

Lentiviral CAR transfer to primary human T cells

Transduction was performed 24 hours after the start of stimulation by spinoculation with lentiviral supernatant (multiplicity of infection of 1) and protamine sulfate (1 mg/mL; APP Pharmaceuticals). Transduced cells were removed from the stimulation plate after 24 hours.

Generation of TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell lines

TCR/CD3-CAR transfer to NK-92 cells was performed similarly to CAR transfer to T cells, albeit with SF Cell Line Nucleofector Solution, AAVS1-targeting single guide RNA, and the electroporation program CA-137. CAR+ cells were MACS-enriched twice using myc-tag-specific phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibody (clone 9B11; Cell Signaling Technology Inc) and anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi).

VITAL assay22 to assess the cytotoxicity of CAR NK-92 and CAR T-cell lines

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled, wild-type T cells (target [T] cells) and dichloro dimethyl acridin one succinimidyl ester (DDAO)-labeled TCR/CD3-KO T cells (control [C] cells) were mixed in a 1:1 cellular ratio at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells of each type. This mixture was seeded at 100 μL per well in a 96-well round-bottomed plate. Unlabeled effector (E) NK-92 cells were added at the indicated E:T:C ratios. After 4 and 16 hours, the E:T ratios and counts were assessed using a Cytoflex LX device (Beckman Coulter), which was used for flow cytometry analyses. Relative cytotoxicity was calculated by normalizing the T:C ratios of samples with effector cells to the T:C ratio of control samples without effectors using this formula: relative cytotoxicity = 1 – ([T:C]sample ÷ [T:C]control). For CD19-CAR T cells, the assay was performed similarly, albeit with green fluorescence protein–tagged Nalm-6 target cells and red fluorescence protein–tagged CD19-KO Nalm-6 control cells.

TCR– T-cell purification

Wild-type and gene-modified NK-92 cells were harvested, gamma-irradiated at 30 Gy with a GSR-D1 radiation machine (Gamma-Service Medical GmbH), and resuspended in T-cell medium before use. Cocultures were performed in 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates (Corning Inc) for optimization studies and in G-Rex 6-well Cell Culture Plates (Wilson Wolf Corporation) for upscaling tests. For the first coculture, CD19-CAR T cells were seeded at 0.5 × 106 per 24-well plate and 10 × 106 per G-Rex 6-well plate. Residual TCR/CD3+ T-cell frequencies were assessed every 2 or 3 days via flow cytometry. MACS-mediated TCR/CD3+ cell removal was performed using CD3 microbeads and LD depletion columns (Miltenyi).

Intracellular cytokine analysis via flow cytometry

Effector T cells (CD19-CAR T cells and wild-type T cells) were rested in cytokine-free medium for 48 hours and then split into 4 conditions on a round bottom 96-well plate: (1) no stimulation, (2) coculture with CD19+ green fluorescence protein–tagged Nalm-6 cells, (3) coculture with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific) labeled (CD19-) Jurkat cells, and (4) polyclonal stimulation in a medium containing 10 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma Aldrich) and 2.5 μg/mL ionomycin (Sigma Aldrich). Brefeldin A (Sigma Aldrich) was added (at 10 μg/mL) after 1 hour. After 16 hours, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, stained with fixable blue dead-cell stain dye, washed again, fixed, and permeabilized using the Intracellular Fixation & Permeabilization Buffer Set (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before intracellular staining (supplemental Table 3).

Data analysis and presentation

Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo Software (BD). Graphs were created with Prism 9 (Graphpad).

Results

Generation of TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK92 cell lines

For the purpose of TCR/CD3+ T-cell depletion using TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cells (Figure 1A), we rationally designed 4 TCR/CD3 complex-targeting myc-tagged, second-generation CARs. For antigen recognition domains, we tested 1 scFv specific for CD3ε (clone OKT3; patent US5929212A) and 1 scFv specific for TCRα/β dimers (clone BMA03123-25). Each scFv was fused with both CD28.CD3ζ and a CD8α.4-1BB.CD3ζ CAR stalk, thus creating 4 TCR/CD3-specific CARs termed from CAR1 to CAR4 (Figure 1B). CAR expression cassettes were flanked by sequences identical to the AAVS1 safe-harbor locus (homology arms; supplemental Table 2). These HDR templates were amplified via polymerase chain reaction and delivered into NK-92 cells via electroporation together with AAVS1-targeting single guide RNA/Cas9 RNP for nuclease-assisted transgene integration into AAVS1. The initial TCR/CD3–CAR+ rates assessed via flow cytometry 2 weeks after electroporation ranged from 3% to 5% and increased to 79% by 2 rounds of MACS via the CAR myc-tag (Figure 1C).

Generation of TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell lines for the removal of residual TCR+ T-cells from TCR-deleted CAR T-cell product. (A) Outline of the cell-mediated purification strategy. Gamma-irradiated NK-92 cells equipped with a TCR/CD3-specific CAR are added to expanding TCR– CAR T-cells. This coculture then leads to the removal of residual TCR-wild-type T-cells from the TCR– CAR T-cell product. (B) Generation of TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell lines by site-specific integration of 4 CAR transgenes (termed CAR1-CAR4), with specificity for either the TCRα/β dimer or CD3ε in the human AAVS1 safe-harbor locus. (C) CAR expression after knockin (left) and MACS-enrichment. (D,E) Experimental setup and results of flow cytometric VITAL assays used to test target-specific cytotoxicity of the 4 TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell lines. The VITAL assays were set up as cocultures of unlabeled effector (E) TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cells, DDAO-labeled C cells TRAC-KO (TCR-negative) T-cells, and CFSE-labeled target (T) wild-type T-cells. Relative killing was calculated from T:C ratios at 4 and 16 hours after the start of the coculture.

Generation of TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell lines for the removal of residual TCR+ T-cells from TCR-deleted CAR T-cell product. (A) Outline of the cell-mediated purification strategy. Gamma-irradiated NK-92 cells equipped with a TCR/CD3-specific CAR are added to expanding TCR– CAR T-cells. This coculture then leads to the removal of residual TCR-wild-type T-cells from the TCR– CAR T-cell product. (B) Generation of TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell lines by site-specific integration of 4 CAR transgenes (termed CAR1-CAR4), with specificity for either the TCRα/β dimer or CD3ε in the human AAVS1 safe-harbor locus. (C) CAR expression after knockin (left) and MACS-enrichment. (D,E) Experimental setup and results of flow cytometric VITAL assays used to test target-specific cytotoxicity of the 4 TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell lines. The VITAL assays were set up as cocultures of unlabeled effector (E) TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cells, DDAO-labeled C cells TRAC-KO (TCR-negative) T-cells, and CFSE-labeled target (T) wild-type T-cells. Relative killing was calculated from T:C ratios at 4 and 16 hours after the start of the coculture.

Initial testing of 4 CAR NK-92 cell lines

Cytotoxicity of the gene-modified NK-92 cell lines was assessed using VITAL assays,22 which are cocultures of 3 cell types: (1) effector (E) cells, the TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cells; (2) target (T) cells, fluorescently labeled (CFSE) wild-type T cells, and (3) control (C) cells, which were fluorescently labeled (DDAO) TRAC-KO (TCR/CD3–) T cells (Figure 1D). Wild-type and CD19-specific CAR NK-92 cells served as irrelevant effectors. Cocultures were set up at E:T:C ratios ranging between 1/8:1:1 and 8:1:1. After 4 and 16 hours, the T:C ratios of the surviving cells were detected via flow cytometry to determine the target-specific cytotoxicity of effector cells. Three of the 4 TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cell lines showed high target-specific cytotoxicity toward TCR/CD3-KO T cells, exceeding 80% in the highest E:T:C ratio after 4 hours (Figure 1E, left). Although absolute target cell killing was nearly complete at high-E:T:C ratios, the absolute counts of TCR/CD3-KO control cells were only moderately affected, indicating low off-target cytotoxicity of the redirected NK-92 cell lines, despite the presence of CAR-activating target cells. (Figure 1E, middle and right).

Selection of 1 CAR NK-92 cell line for the depletion of unedited T cells after TCR-KO

Next, we tested the ability of candidate cell lines to selectively eradicate the remaining fraction of potentially alloreactive TCR/CD3+ (wild-type) T cells within the expanding TCR/CD3-KO CAR T cells. Such TCR/CD3-deleted CAR T cells were generated via the site-specific TRAC integration of the CAR transgene, as previously reported10 (Figure 2A). On day 7 after T-cell isolation, TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cells were added to the expanding CAR T cells at a T:NK-92 cell ratio of 1:2. Before use, NK-92 cells were subjected to gamma irradiation at 30 Gy (supplemental Figure 1), a standard safety measurement taken before clinical application of such cell lines to prevent their outgrowth while retaining their short-term cytotoxicity.20 The purity of the expanding CAR T cells was monitored over the next 12 days until day 19 after T-cell isolation using CD3 as a surrogate marker for TCR surface expression. The single administration of all 4 CAR NK-92 cell lines led to an immediate reduction in residual wild-type TCR/CD3+ T cells. Administration of CAR4 NK-92 cells resulted in the strongest decline in the TCR/CD3+ population from 24.2% in the untreated sample to 0.14% (on day 11 after T-cell isolation), marking a removal of 99.4% of the residual wild-type T cells. The reappearance of wild-type T cells starting 6 days after CAR NK-92 cell administration was observed in all 4 CAR NK-92 cell lines, with CAR3 being the highest (Figure 2B). The lowest frequency of residual TCR/CD3+ cells at the end of the CAR T-cell expansion phase was achieved with the CAR4 NK-92 cell line (1.5% TCR/CD3+ cells), which was selected for further studies. In a separate experiment, we aimed to study the mechanism of action of coculture-induced wild-type T-cell removal. Inhibition of CAR activation in irradiated NK-92 cells using the tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib prevented the elimination of TCR+ T cells, confirming that the lysis of wild-type T cells is dependent on CAR NK-92 activation within the first 24 hours of coculture (supplemental Figure 2).

Selection of TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell line with the highest purification efficacy. (A) Experimental setup for nonviral TCR-to-CAR replacement (in T cells) and subsequent NK-92 cell-mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells. (B) Flow cytometric detection of residual TCR-wild-type T cells after coculture with TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cells (left) or under control conditions (upper right) and summary of data (bottom right).

Selection of TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell line with the highest purification efficacy. (A) Experimental setup for nonviral TCR-to-CAR replacement (in T cells) and subsequent NK-92 cell-mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells. (B) Flow cytometric detection of residual TCR-wild-type T cells after coculture with TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cells (left) or under control conditions (upper right) and summary of data (bottom right).

A second administration of CAR NK-92 cells increases CAR T-cell product purity

Because a single CAR4 NK-92 cell administration was insufficient for the sustained removal of wild-type T cells, we compared single and 2 consecutive coculture cycles (Figure 3A). To do so, we generated 4 TCR/CD3-deleted CAR T-cell lines from 2 healthy donors, using 2 different editing strategies in parallel: lentiviral gene transfer with subsequent TRAC KO and TRAC integration of the CAR transgene. Six days after the initial coculture (day 13 after T-cell isolation), toward the late phase of a typical CAR T-cell product expansion phase, purity of TCR/CD3-deleted CAR T cells was 84.9% without, 99.8% with a single, and >99.98% with 2 rounds of CAR4 NK-92 cell administration (Figure 3B,C). The residual TCR/CD3+ fractions were 15.1%, 0.21%, and 0.017%, respectively. This translates to a removal of 98.6% of residual wild-type T cells through a single administration and 99.9% through 2 cocultures. In comparison, CD3-MACS depletion, also performed on day 13 after - cell isolation, only increased the product purity from 88.1% to 99.68% (with 0.32% residual wild-type T cells), which translates to a removal of contaminating TCR/CD3+ T cells of only 97.3% (Figure 3D). Thus, wild-type T-cell frequencies were ∼19-fold lower after purification using our method than after CD3-MACS depletion. The degree of product purity can also be examined by calculating the number of edited T cells per unedited (wild-type) T cell (CD3–-to-CD3+ ratio; Figure 3E). The large divergence in this parameter highlights the significant difference between the efficiencies of the 2 approaches. Importantly, at this small scale, we did not observe any significant changes in the total CD3– T-cell counts or memory phenotype within the final CAR T-cell product (supplemental Figure 3A,B). Interestingly, the CD4:CD8 ratios switched toward a more balanced state from 1:5.7 without and 1:4.4 with a single, to 1:3.1 with 2 treatment cycles. This appeared to be a general effect of NK-92 cell coculture, because a similar shift was observed after coculture with unmodified NK-92 cells (supplemental Figure 3C).

Optimization of TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell–mediated purification and comparison with MACS-mediated CD3-depletion. (A) Experimental setup for lentiviral (LV) or virus-free TCR-to-CAR replacement and subsequent NK-92 cell–mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells in 1 or 2 coculture cycles. n = 4, TRAC-edited CAR T-cell lines derived from 2 donors (per donor: 1 × LV CAR gene transfer + TRAC-KO and 1 × TRAC-CAR knockin). (B) From left to right: representative flow cytometry dot plots of virus-free TRAC-integrated CAR T cells when cultured alone, after 2 coculture cycles with unedited NK-92 cells, after MACS-mediated CD3-depletion (independent experiment), or after 1, or 2 coculture cycles with TCR/CD3-specific (CAR4) NK-92 cells. (C) Summary of purity, impurity (in terms of the residual TCR/CD3+ cells), and cleaning efficiency (relative reduction of the CD3+ fraction) after 0, 1, or 2 coculture cycles. (D) Impurity and cleaning efficiency after MACS-mediated CD3-depletion (left, independent experiment; n = 12) or coculture with TCR/CD3-specific (CAR4) NK-92 cells. Data point shapes: triangular, LV gene transfer; round, virus-free gene transfer. (E) Ratio of successfully edited (TCR/CD3-) cells per residual unedited (TCR/CD3+) wild-type cell.

Optimization of TCR/CD3-CAR NK-92 cell–mediated purification and comparison with MACS-mediated CD3-depletion. (A) Experimental setup for lentiviral (LV) or virus-free TCR-to-CAR replacement and subsequent NK-92 cell–mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells in 1 or 2 coculture cycles. n = 4, TRAC-edited CAR T-cell lines derived from 2 donors (per donor: 1 × LV CAR gene transfer + TRAC-KO and 1 × TRAC-CAR knockin). (B) From left to right: representative flow cytometry dot plots of virus-free TRAC-integrated CAR T cells when cultured alone, after 2 coculture cycles with unedited NK-92 cells, after MACS-mediated CD3-depletion (independent experiment), or after 1, or 2 coculture cycles with TCR/CD3-specific (CAR4) NK-92 cells. (C) Summary of purity, impurity (in terms of the residual TCR/CD3+ cells), and cleaning efficiency (relative reduction of the CD3+ fraction) after 0, 1, or 2 coculture cycles. (D) Impurity and cleaning efficiency after MACS-mediated CD3-depletion (left, independent experiment; n = 12) or coculture with TCR/CD3-specific (CAR4) NK-92 cells. Data point shapes: triangular, LV gene transfer; round, virus-free gene transfer. (E) Ratio of successfully edited (TCR/CD3-) cells per residual unedited (TCR/CD3+) wild-type cell.

Additional optimization and extended monitoring during expansion

Next, we evaluated additional parameters to improve the purity of TCR– CAR T-cell-products: (1) different T-cell–to–CAR4-NK-92 cell ratios (conditions from 1:1 to 1:4), (2) time span between the cocultures (conditions, A: 2 days and B and C: 3 days), and (3) a third coculture (3× clean-up). In regimens 1:2A and 1:2C, both cocultures were performed at a 1:2 T-cell-to-CAR4-NK-92 ratio, whereas for regimen 1:2B, the second coculture was performed at a 1:1 ratio. CAR T cells were monitored over an extended time frame until day 43 after T-cell isolation (supplemental Figure 4). Higher CAR4 NK-92 presence during coculture and an additional third clean-up coculture improved the purity. Similarly, increasing the time between the first and second coculture led to enhanced purity and longer TCR depletion. However, the conditions 1:2A and 1:2B were determined to be the most reasonable for subsequent scaling experiments aiming to develop a streamlined CAR T-cell production process with as few interventions and NK-92 cells as possible.

CAR NK-92 cell–mediated depletion can be scaled within the G-Rex bioreactor system

Because of the high-volume requirement of allogeneic CAR T-cell manufacturing and the need for a closed or semiclosed system, we tested whether cell-mediated clean-up could be feasible in a G-Rex cell culture device, simulating a good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compatible approach. We compared CD3-MACS depletion (on day 13 after T-cell isolation) with 2 consecutive cocultures (starting on day 5 after T-cell isolation) spaced by 2 or 3 days (conditions 1:2A and 1:2B, respectively, as specified in supplemental Figure 4; Figure 4A). With average TCR+ T cells of 0.026% (1:2A) and 0.007% (1:2B), both CAR4 NK-92 approaches yielded higher purity than MACS (mean, 3.1% of TCR+ cells) on day 14 after T-cell isolation (Figure 4B). Respectively, this marks a 12- and 45-fold decrease in residual TCR/CD3+ contaminations compared with the MACS results shown in Figure 2. Thus, both coculture regimens yielded ultrapure products, with TCR- rates exceeding 99.97% and 99.99%. Intriguingly, we observed an improved expansion of CAR T cells in the presence of CAR4 NK-92 cells, increasing total T-cell yields three- to sixfold compared with unpurified or MACS-purified CAR T cells (Figure 4C). Importantly, NK-92 cells were undetectable in CAR T-cell products cryopreserved on day 14 after T-cell isolation (supplemental Figure 5).

Characterization of G-Rex-expanded TCR/CD3-depleted CAR T-cell products. (A) Experimental setup for nonviral TRAC integration of CD19-CAR into primary human T cells and subsequent CAR4 NK-92 cell–mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells. (B-E) Product characteristics on day 14 after T-cell isolation: (B) residual TCR/CD3+ (wild-type) T-cell fraction (unpurified refers to the condition previously termed as T cells only); (C) normalized total cell counts; (D) CD8:CD4 ratios; and (E) TCRα/β:TCR γ/δ ratios within residual CD3+ T-cell fractions. (F) 6 hour VITAL assay to assess the target-specific cytotoxicity of differently purified CD19-CAR T cells. (G) Intracellular cytokine expression assay to assess the effector function of CD19-CAR T cells after CD19+ target cell encounters. mock-E, mock-electroporated wild-type T-cell controls.

Characterization of G-Rex-expanded TCR/CD3-depleted CAR T-cell products. (A) Experimental setup for nonviral TRAC integration of CD19-CAR into primary human T cells and subsequent CAR4 NK-92 cell–mediated depletion of residual TCR-unedited cells. (B-E) Product characteristics on day 14 after T-cell isolation: (B) residual TCR/CD3+ (wild-type) T-cell fraction (unpurified refers to the condition previously termed as T cells only); (C) normalized total cell counts; (D) CD8:CD4 ratios; and (E) TCRα/β:TCR γ/δ ratios within residual CD3+ T-cell fractions. (F) 6 hour VITAL assay to assess the target-specific cytotoxicity of differently purified CD19-CAR T cells. (G) Intracellular cytokine expression assay to assess the effector function of CD19-CAR T cells after CD19+ target cell encounters. mock-E, mock-electroporated wild-type T-cell controls.

Characterization of TCR/CD3-depleted CD19-CAR T-cell products

We observed an increased proportion of CD4 T cells after expansion in conditions treated with irradiated CAR4 NK-92 cells compared with nonpurified or MACS-depleted CAR T cells (Figure 4D). The residual TCR/CD3+ T cells were analyzed for the TCR subtype. Both MACS and CAR-NK92 purified CAR T cells showed more TCRγ/δ+ cells than the unpurified controls (Figure 4E). Condition 1:2B diminished the relative frequency of TCRα/β+ T cells to below 10%. Phenotypical analysis of CAR T cells demonstrated no significant impact on the expression of the inhibitory receptors, Lag-3, Tim-3, and PD-1, which are usually associated with T-cell exhaustion (supplemental Figure 6A). In line with this improved expansion, there was a trend toward a relative increase in T cells expressing an effector memory phenotype (CCR7– CD45RA–) (supplemental Figure 6B). In addition, we assessed CD19-CAR–dependent killing and cytokine production as parameters of CAR T-cell product functionality (Figure 4F,G). In a 6 hour VITAL assay, CD19-CAR T cells induced dose-dependent lysis of CD19+ Nalm-6 cells, regardless of the chosen purification method (Figure 4F). Similarly, the frequency of cytokine-producing CD19-CAR+ T cells upon tumor challenge was independent of the purification method (Figure 4G).

Discussion

Here, we present a novel strategy for purifying TCR– CAR T cells via coculture with gamma-irradiated TCR/CD3-specific CAR NK-92 cells during ex vivo expansion. Upon selection of an efficient CD3-specific CAR construct and optimization of the coculture conditions, the average TCR/CD3+ fractions were below 0.01% using the semiclosed G-Rex system. This marks a >45-fold improvement over MACS results obtained internally (0.32%) and a >100-fold improvement compared with previous studies on TCR-edited CAR T cells preparing or performing clinical trials (up to 1.1%), respectively.11-13,18 This in-process purification replaces the need for bead-based depletion procedures. Furthermore, it avoids the need for repeated T-cell transfection required by the purification strategy described by Juillerat et al,19 who electroporated CD3-CAR messenger RNA 2 days after TCR disruption. Our approach streamlined cell handling and avoided MACS- or transfection-associated cell loss, thereby improving the cost-per-dose ratio of the allogeneic production process.1

Depending on the CAR+ rate in the final CAR T-cell product, a GVHD threshold of 5×104 TCRα/β+ cells per kg of body weight can be reached rapidly, even at low therapeutic doses. At an exemplary CAR+ rate of 20%, a residual TCRα/β fraction of 1% (previously reported MACS purification results) would allow for a maximum dose of 1 × 106 CAR+ cells per kg body weight, which is in the very low therapeutic range, whereas TCR/CD3+ rates <0.05% obtained in this study even allow for very high CAR T-cell doses exceeding 20 × 106 CAR+ cells per kg body weight (supplemental Table 1). This is of paramount importance given the dose-response relationship of CAR T-cell therapy.17 Further, more absolute residual TCRα/β+ T cells should be associated with a higher TCRα/β diversity and could increase the likelihood of the presence of alloreactive TCRs specific for a given patient genotype. During prolonged in vitro culture, we observed limited recovery of TCR/CD3+ cells, which reached a plateau at around day 20 after the initial coculture (supplemental Figure 4). Most of the residual CD3+ T cells in CAR-NK92 purified cell products displayed TCRγ/δ, which does not contribute to GVHD26,27 (Figure 4E). Although further optimization of the coculture conditions could presumably reduce this recovery, its clinical relevance remains unclear. Potentially, future studies should examine the TCR repertoire of residual TCR/CD3+ T cells and the occurrence of xenogeneic GVHD in vivo, using tumor models in immunodeficient mice.28

Autologous or allogeneic feeder cells are used in many protocols for CAR T-cell generation in preclinical and also clinical settings.29-31 We show that gamma-irradiated CD3-CAR NK-92 cells support CAR T-cell expansion and do not affect their in vitro effector functionality in terms of antigen-dependent cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion (Figure 4). In contrast to the strategy of Juillerat et al,19 CAR-NK92 purified T cells were not subjected to antigen-mediated CAR activation during expansion. Consequently, phenotyping of CAR T cells revealed no relevant changes in the memory phenotype composition or expression of inhibitory receptors associated with exhaustion using our optimized procedure (1:2B; supplemental Figure 6). Potentially, increased CAR T-cell yields may be partially attributed to a better expansion of CD4+ CAR T cells, because we observed a trend toward higher CD4+ frequencies (supplemental Figure 3; Figure 4). Future studies should investigate the effects of changes in the CD4:CD8 ratio and identify the optimal medium composition for an enhanced CAR T-cell memory phenotype and antitumor performance in vivo.

The presented novel purification approach comes along with limitations. CAR4 NK-92 cells may be unsuitable for the production of major histocompatibility complex class 1–silenced CAR T-cell products (eg, through B2M KO) because NK-92 cells target major histocompatibility complex class 1–negative cells via missing-self-activation.2,32 Hypoimmunogenic B2M-KO cell products overexpressing NK cell inhibitory receptors, such as HLA-E33,34 or CD47,35,36 may be combined with our NK-92 cell-based approach. As the CAR4 construct binds to CD3ε regardless of the TCR subtype, it is unsuitable for the expansion of TCRγ/δ T cells. However, this purification system could be adopted to specifically deplete TCRα/β T cells by optimizing our TCRα/β-specific constructs.

Before clinical use, the CAR4 NK-92 cell line must be established as a master cell bank under GMP conditions.1 Building on GMP-compatible protocols,10,37,38 we assume that large-scale production of CAR T cells may be performed by combining nonviral gene editing and coculture with CAR NK-92 in bioreactor systems such as the semiclosed G-Rex system30 or automated cell manufacturing devices.39 This approach could be adapted for other donor-derived CAR T-cell products previously described, such as for the treatment of leukemia relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,40 T-cell malignancies,13,41,42 multiple myeloma,37 and, potentially, even solid tumors.38 Because of the previous clinical application of gamma-irradiated NK-92 cells,20,43 process development with CAR4 NK-92 mediated purification should be feasible. Nevertheless, release testing of CAR T-cell products should include the detection of residual live CAR4 NK-92 cells because of their potential to deplete the patient’s T cells in vivo. Furthermore, NK-92 cell–derived debris can reside in the product at a percentage, depending on the T-cell expansion rate, culture duration, and product formulation. To minimize the risk of infusion-related toxicities, it is advisable to reduce the presence of debris during product formulation, which can be achieved through methods such as counterflow centrifugation.44 A GMP-compliant CAR4 NK-92 master cell bank may also have potential as a stand-alone cell therapy for treating T-cell malignancies.45 Nevertheless, the safety and efficacy of this approach require further investigation in future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tatiana Zittel (Charité) for technical assistance. Illustrations were created using BioRender.com.

The study was supported by a grant fromthe Arab-German Young Academy of Sciences and Humanities, facilitated by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (M.A.-e.-E.), the Einstein Center for Regenerative Therapies research grant (J.K., S.M., H.-D.V., M.S.-H., P.R., and D.L.W.), and an ECRT kickbox grant for young scientists (J.K., W.D., S.M., and M.E.). The work of M.A.-e.-E. is supported, in part, by the award P30CA014089 from the US National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute. J.K. and D.L.W. acknowledge the support of the SPARK-BIH program by the Berlin Institute of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: J.K. designed this study, planned and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; W.D., S.M., and M.E. planned and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; C.F., L.H., V.D., and V.G. performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and edited the manuscript. M.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the results; M.S.-H., P.R., H.-D.V., and M.A.-e.-E. interpreted the data and edited the manuscript; M.A.-e.-E. provided inputs on the design of this study and obtained part of the funding for this study; D.L.W. designed and led the study, planned experiments, analyzed results, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors discussed, commented on, and approved the manuscript in its final form.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.K., D.L.W., M.A.-e.-E., S.M., M.E., and W.D. are listed as inventors on a patent application filed by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, which is based on the data presented in this manuscript. H.-D.V. is founder and the CSO at CheckImmune GmbH. P.R., H.-D.V., and D.L.W. are cofounders of the startup TCBalance Biopharmaceuticals GmbH focused on regulatory T-cell therapy. J.K., W.D., M.S.-H., P.R., H.-D.V., and D.L.W. are listed as inventors on patent applications unrelated to the presented work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonas Kath, Berlin Center for Advanced Therapies, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: jonas.kath@charite.de; and Dimitrios L. Wagner, Berlin Center for Advanced Therapies, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: dimitrios-l.wagner@charite.de.

References

Author notes

∗D.L.W. and M.A.-e.-E. are joint senior authors.

All construct sequences used in this study are given in supplemental Table 2.

The cell lines and other underlying data are available on request from the corresponding author, Dimitrios L. Wagner (dimitrios-l.wagner@charite.de).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.