TO THE EDITOR:

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to millions of infections and deaths worldwide. Patients with cancer and particularly those with hematologic malignancies showed an increased probability of a severe outcome including death.1 Immense efforts led to a rapid development of vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections.2,3

Despite the high efficacy of the vaccination, the benefit for severely immunocompromised patients such as those undergoing anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies is still uncertain. After CAR-T therapy, patients often display a long-term B-cell depletion and presumably do not develop proper humoral immunity in response to vaccinations. In line, only 11% to 36% of patients vaccinated after CAR-T therapy developed antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2–derived spike (S) protein.4,5 However, it remains unknown whether these patients still benefit from vaccination by developing cellular immunity. At present, most patients treated with CAR T cells are vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, which is why the question of whether CAR-T therapy has an impact on preexisting cellular or humoral immune responses is gaining increasing relevance.

Here, we sought to analyze whether patients vaccinated after CAR-T therapy develop cellular immunity despite lacking antibody levels and whether vaccination before CAR-T therapy allows for sustained immunity throughout and beyond lymphodepletion and CAR-T therapy. Therefore, we analyzed humoral and cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in 21 and 15 patients vaccinated before and after CAR-T therapy, respectively. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of all patients, with none of them having a confirmed COVID-19 infection diagnosis before the vaccination. Furthermore, 15 convalescent donors and 15 vaccinated healthy controls (HCs) served as the control group.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| Patient characteristics . | n = 36 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 65 (19-83) |

| Age <65 y, n (%) | 16 (44) |

| Disease, n (%) | |

| DLBCL | 20 (56) |

| Other NHL | 9 (25) |

| Other | 7 (19) |

| CD19 CAR T-cell product, n (%) | |

| Tisa-cel | 10 (28) |

| Axi-cel | 10 (28) |

| Other | 16 (44) |

| Status of disease, n (%) | |

| Remission | 31 (86) |

| Refractory | 5 (14) |

| Postinfusion complications and related treatments, n (%) | |

| CRS | 27 (75) |

| ICANS | 13 (36) |

| Corticosteroids | 14 (39) |

| anti-IL-6R | 27 (75) |

| Vaccination type, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) | 23 (64) |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 4 (11) |

| Vakzevria (AstraZeneca) | 4 (11) |

| Vakzevria/BNT162b2 | 5 (14) |

| Circulating B cells at vaccination, n (%) | 17 (46) |

| Days from CAR T-cell therapy to vaccination (n = 15), median (range) | 257 (115-817) |

| Days from vaccination to CAR T-cell therapy (n = 21), median (range) | 208 (70-365) |

| Patient characteristics . | n = 36 . |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 65 (19-83) |

| Age <65 y, n (%) | 16 (44) |

| Disease, n (%) | |

| DLBCL | 20 (56) |

| Other NHL | 9 (25) |

| Other | 7 (19) |

| CD19 CAR T-cell product, n (%) | |

| Tisa-cel | 10 (28) |

| Axi-cel | 10 (28) |

| Other | 16 (44) |

| Status of disease, n (%) | |

| Remission | 31 (86) |

| Refractory | 5 (14) |

| Postinfusion complications and related treatments, n (%) | |

| CRS | 27 (75) |

| ICANS | 13 (36) |

| Corticosteroids | 14 (39) |

| anti-IL-6R | 27 (75) |

| Vaccination type, n (%) | |

| BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) | 23 (64) |

| mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 4 (11) |

| Vakzevria (AstraZeneca) | 4 (11) |

| Vakzevria/BNT162b2 | 5 (14) |

| Circulating B cells at vaccination, n (%) | 17 (46) |

| Days from CAR T-cell therapy to vaccination (n = 15), median (range) | 257 (115-817) |

| Days from vaccination to CAR T-cell therapy (n = 21), median (range) | 208 (70-365) |

anti-IL-6R, anti–interleukin 6 receptor (tocilizumab); Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; mRNA, messenger RNA; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; Tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel.

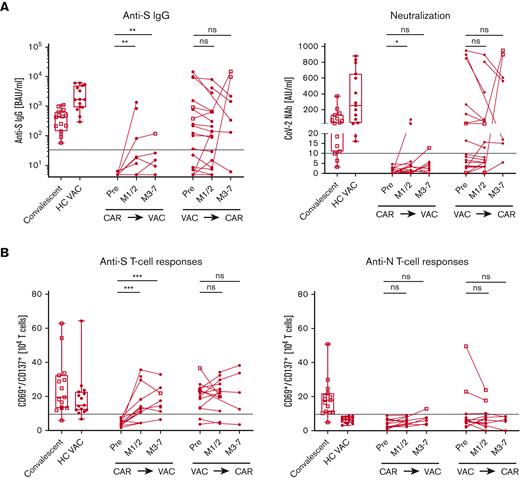

First, we tested 15 patients who received CAR-T therapy before SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (Figure 1A-B). Of 15 patients, 13 were still completely B-cell depleted at the time of vaccination. CAR T cells were detected in 10 patients (supplemental Table 1). Consistent with recent studies,4-6 only 2 (13%) of the patients developed neutralizing antibodies. In contrast, all convalescent donors and vaccinated HCs developed anti-S immunoglobulin G (IgG), with most of them being virus neutralizing. To determine whether patients may develop a humoral response over time, we repeated antibody measurements in 7 patients, 3 to 7 months after vaccination, but no patient seroconverted. Furthermore, we tested 21 patients vaccinated before undergoing lymphodepletion and CAR-T treatment. Interestingly, the humoral responses in previously vaccinated patients who received CAR-T therapy remained largely unchanged with a slight decline in antibody response compared with healthy individuals. For 2 patients, an antibody increase was observed due to a reported infection. After the exclusion of these, all 8 previously seropositive patients remained positive for neutralizing antibodies, and all 10 of 11 seronegative patients remained negative. One patient seroconverted, which might be explained by an unrecognized infection. All participants gave their informed, written consent. The study has been performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Sample collection and analysis were approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Center, University of Erlangen, Germany (protocol 118_20B, 174_20B, 19-336_1-B).

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune responses in patients who received CAR T-cell therapy. Patients after CAR T-cell therapy (CAR⇛VAC), before (pre), and 1 to 2 months (M1/2), and 3 to 7 months (M3-7) after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and patients after vaccination (VAC⇛CAR), before and 1 to 2 months (M1/2), and 3 to 7 months (M3-7) after CAR T-cell therapy were analyzed for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune responses. Convalescent patients (n = 15, open square) and HCs after vaccination (HC VAC, n = 15, circles) were used as controls. (A) Graph shows the humoral response with anti-spike IgG (left) and neutralizing antibody activity (right). (B) Cellular response to anti-spike (left) and antinucleocapsid–specific T cells (right) is graphed. Individual patients were interconnected; dotted line depicts the cutoff for positivity as indicated in the “Methods.” Square symbols were used for patients after a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Box plots depict the 75th percentile, median, and 25th percentile values, and whiskers represent maximum and minimum values. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. AU, arbitrary units; BAU, binding antibody units; ns, not significant.

Anti–SARS-CoV-2 immune responses in patients who received CAR T-cell therapy. Patients after CAR T-cell therapy (CAR⇛VAC), before (pre), and 1 to 2 months (M1/2), and 3 to 7 months (M3-7) after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and patients after vaccination (VAC⇛CAR), before and 1 to 2 months (M1/2), and 3 to 7 months (M3-7) after CAR T-cell therapy were analyzed for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune responses. Convalescent patients (n = 15, open square) and HCs after vaccination (HC VAC, n = 15, circles) were used as controls. (A) Graph shows the humoral response with anti-spike IgG (left) and neutralizing antibody activity (right). (B) Cellular response to anti-spike (left) and antinucleocapsid–specific T cells (right) is graphed. Individual patients were interconnected; dotted line depicts the cutoff for positivity as indicated in the “Methods.” Square symbols were used for patients after a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Box plots depict the 75th percentile, median, and 25th percentile values, and whiskers represent maximum and minimum values. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. AU, arbitrary units; BAU, binding antibody units; ns, not significant.

Although only a minority of patients developed protective antibody titers, for patients vaccinated after CAR-T therapy, most (13 of 15, 87%) developed S-specific T-cell responses (Figure 1B). Again, in patients vaccinated before CAR-T therapy, the immune response was sustained throughout the treatment with a constant 88% (14 of 16 patients) T-cell response rate. Specificity of responses was shown for HCs by the new occurrence of these anti-S–specific T cells after vaccination. The measured T-cell response consisted of CD4 and CD8 T cells with a higher proportion of CD4 T cells in both cohorts (supplemental Figure 1). As expected, most of the convalescent donors (14 of 15, 93%) showed anti-N T-cell responses (Figure 1B). Follow-up for up to 7 months showed relatively constant immune responses.

Taken together, the presence of circulating B cells and vice versa loss of CAR T cells do not appear to be the only requirements for humoral responses. In both the groups of patients with seroconversion, patients vaccinated after CAR-T therapy and in most seropositive patients (10 of 13 patients) vaccinated before CAR-T therapy, B cells were detectable. In addition, 73% of the nonresponders of the patients vaccinated before CAR-T therapy showed circulating B cells. Moreover, we observed no differences in absolute T-cell or CD4 T-helper cell numbers in responders vs nonresponders in either of the patient cohort. No other parameter, including patient characteristics, type and timing of vaccination, IgG level, and side effects due to CAR-T therapy, seemed to have an impact on the immune responses (supplemental Table 1). We cannot exclude that missing correlations are due to the limited study population.

The low humoral response rates in CAR-T recipients are consistent with recent reports.4-6 In contrast, the incomplete response rates in patients vaccinated before CAR-T treatment might be explained by their underlying diseases. Recent reports describe a lack of humoral immune responses in 21% of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.7 However, our findings indicate that once humoral responses are present, they persist over time with CAR-T therapy at least for the period considered here. The persistence of plasma cells even 25 months after CAR-T infusion in the absence of B cells8 serves as a possible explanation for the maintained humoral immune response in these patients who received CAR-T therapy.9

Interestingly, we detected a cellular response in 87% of vaccinated patients previously exposed to CAR-T therapy. This was independent from the humoral immunity, CAR-T therapy–related complications, or circulating CAR T cells. First reports of convalescent hematologic patients describe that CD8+ T cells in particular lead to recovery from COVID-19 in the case of B-cell aplasia10 and confirm the importance of cellular responses. New vaccination approaches mainly addressing T-cell immunity should be considered for patients with B-cell deficiency in the future.11 In addition, booster vaccinations might be beneficial for this patient population. The humoral and cellular response rate after a third vaccination increased in patients after allogeneic transplantation12,13 and patients treated for B-cell malignancies14 with a primary series of 3 doses and 1 additional booster dose as recommended by the American Society of Hematology and the American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy for the recipients of CAR-T cells.15

The cellular immune response seems to be of particular relevance as SARS-CoV-2 mutations may escape the humoral response.16,17 This immune escape is most prominently displayed by the enormous mutational profile in the B1.1.529 strain with more than 30 mutations in the S protein.18 Nevertheless, recent studies depicted cross-reactivity of T cells after vaccination or convalescence by intact responses of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells against B1.1.529,19 which further underlines the relevance of cellular response.

Although the patient number is limited, our observations showed that most patients benefit from vaccination after CAR-T therapy. This is of special interest because those patients are at a higher risk of severe COVID-19 and fatal outcomes.20,21 The joint recommendation of the American Society of Hematology and the American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy recommends SARS-CoV-2 vaccination as early as 3 months after CAR-T therapy and a vaccine regimen including 4 administrations.15 This is in line with our findings showing effective immune responses in short distance after CAR-T therapy. Our data suggest high and persistent response rates for patients who were vaccinated before CAR-T therapy. The relatively good tolerance of vaccination, also observed for CAR-T recipients, underlines this recommendation.5,6 In addition, during the follow-up, 10 patients had a positive test result for COVID-19 with only mild symptoms and fully recovered.

Taken together, our data confirm strong cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in most patients with severe B-cell depletion after CAR-T therapy. Because most patients vaccinated before CAR-T therapy showed a humoral and cellular response, our study provides evidence for vaccination before CAR-T therapy with subsequent antibody response detection. Although we could not measure protection from infection in this cohort, these data show the necessity to look beyond antibody levels and underline the importance and meaning of vaccination in these vulnerable patients.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank all of the patients and healthy donors who participated in this study. They also thank Florentine Schonath (Core Unit Cell Sorting and Immunomonitoring Erlangen), Dorothea Gebhardt, Lina Meretuk, and Alina Bauer for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Sander Stiftung 2020.045.1, German Research Foundation (VO1835/3-1, MA1351/12-1), Bayerische Forschungsförderung, and Thorwart-Jeska Stiftung and support from the Else Kröner Forschungskolleg (V.B.) and the German Cancer Consortium School of Oncology fellows (V.B.).

Contribution: A.N.K., H.R., V.B., F.M., A.M., M.S., and S.V. designed the research; A.N.K., H.R., K.S., M.A., N.E., A.K., V.L., T.H., and S.V. performed experiments; M.T. and P.I. performed antibody measurements; V.B., B.J., W.R., D.M., S.K., M.L., G.K., F.M., G.S., and A.E.K. repeatedly referred patients; A.N.K., H.R., M.A., C.L., J.V.G., H.B., F.M., and S.V. analyzed and interpreted data; A.N.K., H.R., V.B., M.S., and S.V. wrote the manuscript; and all the authors edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest-disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Simon Völkl, Department of Internal Medicine 5, Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital Erlangen, Schwabachanlage 12, 91052 Erlangen, Germany; e-mail: simon.voelkl@uk-erlangen.de.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Simon Völkl (simon.voelkl@uk-erlangen.de).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

H.R., A.N.K., M.S., and S.V. contributed equally to this study.