Key Points

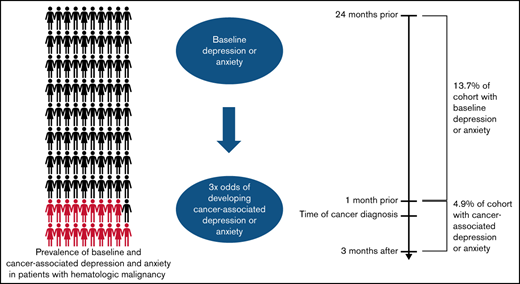

Nearly 1 in 5 blood cancer patients had precancer/cancer-associated depression or anxiety, indicating a need for robust mental health care.

Precancer depression or anxiety conferred the highest odds of developing a new mental disorder around the time of blood cancer diagnosis.

Abstract

For patients with blood cancers, comorbid mental health disorders at diagnosis likely affect the entire disease trajectory, as they can interfere with disease information processing, lead to poor coping, and even cause delays in care. We aimed to characterize the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with blood cancers. Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database, we identified patients ≥67 years old diagnosed with lymphoma, myeloma, leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes between 2000 and 2015. We determined the prevalence of precancer depression and anxiety and cancer-associated (CA) depression and anxiety using claims data. We identified factors associated with CA-depression and CA-anxiety in multivariate analyses. Among 75 691 patients, 18.6% had at least 1 diagnosis of depression or anxiety. Of the total cohort, 13.7% had precancer depression and/or precancer anxiety, while 4.9% had CA-depression or CA-anxiety. Compared with patients without precancer anxiety, those with precancer anxiety were more likely to have subsequent claims for CA-depression (odds ratio [OR] 2.98; 95% CI 2.61-3.41). Other factors associated with a higher risk of CA- depression included female sex, nonmarried status, higher comorbidity, and myeloma diagnosis. Patients with precancer depression were significantly more likely to have subsequent claims for CA-anxiety compared with patients without precancer depression (OR 3.01; 95% CI 2.63-3.44). Female sex and myeloma diagnosis were also associated with CA-anxiety. In this large cohort of older patients with newly diagnosed blood cancers, almost 1 in 5 suffered from depression or anxiety, highlighting a critical need for systematic mental health screening and management for this population.

Introduction

People living with cancer have a substantial burden of mental health disorders and experience significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety compared with the general population.1,2 The odds of being depressed are more than 5 times greater for cancer patients than for the general population.2 Depression and anxiety are not merely distressing conditions; they also result in devastating downstream outcomes such as poor quality of life (QOL),3-5 difficulty processing information,6 delays in cancer treatment,7 nonadherence to guideline-concordant care,8,9 and worse survival.10 Increasing recognition of the psychosocial burden of cancer galvanized the creation of the Institute of Medicine’s 2008 report Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs.11 This report highlighted the importance of psychosocial aspects of oncologic care and proposed a multistep approach of identifying patients with psychosocial needs and incorporating robust psychosocial health services into their care. While attention to solid malignancies has been at the forefront of efforts examining mental health disorders in oncology,7-10,12,13 there is a relative paucity of data on mental health disorders among patients with hematologic malignancies.

Patients with hematologic malignancies have disease presentations and treatment regimens that make them particularly vulnerable to developing mental health disorders. The illness course for many patients with hematologic malignancies is challenging, requiring prolonged hospitalizations with intensive multiagent chemotherapy regimens. Isolation from friends and family in the hospital may also contribute to the development of depression and anxiety. In addition, some hematologic malignancies are incurable at diagnosis (eg, myeloma), which may further increase levels of depression and anxiety. Prior studies examining mental health disorders among patients with hematologic malignancies suggest a concerning burden of depression and anxiety14-17 ; for example, a prospective cohort study of 74 patients hospitalized with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) showed that 39% had symptoms of depression.16 Although these studies provide vital information regarding mental health disorders, many were single-center, included only 1 type of hematologic malignancy, or focused exclusively on either inpatient or outpatient settings,14-17 thus limiting the generalizability of findings.

To further expand the understanding of depression and anxiety among patients with blood cancers, large studies that include patients across various geographic regions and with a broad range of hematologic diagnoses are essential. In addition, characterizing factors associated with developing these disorders in the early phases of the cancer trajectory would be critical in ensuring that the psychosocial needs of this population are addressed in a timely manner. We thus aimed to characterize the prevalence of depression and anxiety in a large population-based cohort of patients with hematologic malignancies. We also sought to identify factors associated with developing these mental health disorders in the first few months of a blood cancer diagnosis. Given prior literature on patients with cancer, we hypothesized that specific sociodemographic factors, such as female sex, and clinical factors, such as comorbidity and underlying precancer mental health disorder,13,14,17 would be associated with higher odds of developing depression or anxiety during the early part of the cancer trajectory.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registry (2000-2015) linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare). SEER collects demographic, clinical, initial cancer-directed treatment, and survival data from 18 population-based cancer registries throughout the United States, representing about 35% of the population. The sociodemographic characteristics of patients in the SEER registries are similar to the general population of the United States. Ninety-seven percent of patients ≥65 years are eligible for Medicare, and approximately 94% of those in the SEER registries are linked to their Medicare enrollment and billing claims data.18 The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Office for Human Research Studies approved the study as nonhuman subject research.

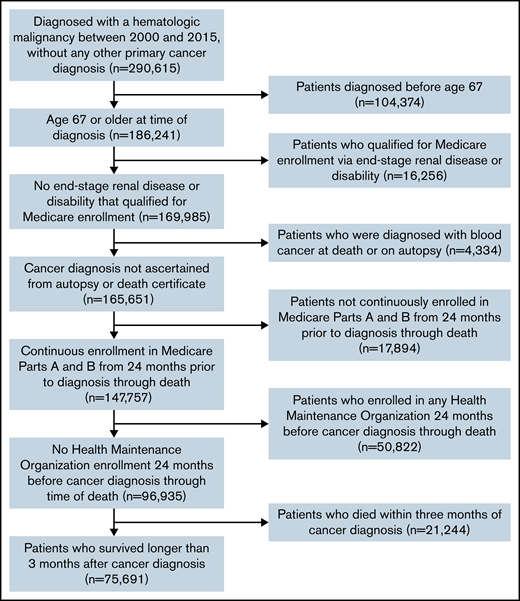

Cohort assembly

Patients aged ≥67 years diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy (lymphoma, myeloma, leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes) as their only cancer diagnosis between 2000 and 2015 were eligible for inclusion. We required patients to be ≥67 years of age at blood cancer diagnosis to ensure a minimum of 2 years of Medicare enrollment prior to diagnosis to ascertain claims for baseline diagnosis of depression and anxiety prior to cancer diagnosis. Patients had to have survived ≥3 months postdiagnosis to enable complete capture of claims for depression and anxiety within that timeframe. To ensure complete claims data, we excluded patients who were not continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B and patients with any health maintenance organization enrollment 24 months prior to blood cancer diagnosis through death. Figure 1 provides details of our cohort selection.

Outcomes

We identified the diagnosis of depression and anxiety using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes from Medicare claims, a method that has been validated to have high specificity for clinical diagnosis of depression (supplemental Table 1).19 We classified patients as having precancer depression (ie, depression preceding cancer diagnosis), precancer anxiety (ie, anxiety preceding cancer diagnosis), cancer-associated depression (CA-depression) (ie, depression presenting around cancer diagnosis), and cancer-associated anxiety (CA-anxiety) (ie, anxiety presenting around cancer diagnosis). We classified patients as having precancer depression or precancer anxiety if they had at least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims for depression or anxiety 24 months to 1 month prior to their hematologic cancer diagnosis. The timeframe of accessing these precancer outcomes is consistent with prior SEER-Medicare studies examining precancer mental health disorders.9,10,12 We classified patients as having CA-depression or CA-anxiety if they had at least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims for depression or anxiety in the 1 month prior to their hematologic cancer diagnosis to 3 months after. We included the 1 month prior to hematologic cancer diagnosis in CA-depression or CA-anxiety as several patients may have already started the work-up of their cancer in the month prior to establishing a pathologic diagnosis; thus, new depression or anxiety in this period may be related to knowledge of an impending cancer diagnosis. We limited the period of inquiry to 3 months after diagnosis because our intent was to focus on the early period after a cancer diagnosis. To be considered part of the CA-depression group, patients could not be in the precancer depression group. Similarly, precancer anxiety was mutually exclusive with CA-anxiety. The rationale for this mutual exclusivity is that if patients already had a preexisting diagnosis of depression prior to their cancer diagnosis, another claim of depression after their cancer diagnosis would not indicate a new diagnosis of depression. Instead, it would represent persistence of an existing diagnosis or recurrence of depression symptoms.

Covariates

Using the SEER-Medicare files, we determined each patient’s age, sex, race, type of blood cancer, and year of diagnosis. Marital status was dichotomized into “married” (including common law) vs “not married.” We assessed comorbidity using the Deyo adaptation20 of the Charlson comorbidity index,21 applied to inpatient and outpatient claims.22 Comorbidities included in this index are congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, liver disease, renal disease, paralysis, dementia, ulcer disease, and diabetes. Median income was defined based on available median household or per capita income by census tract and ZIP code in the SEER-Medicare database and categorized in quintiles. Education quintiles were determined based on the percentage of individuals age ≥25 years with some college education within a census tract. We also characterized each patient’s residence (urban, rural) and their SEER geographic region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West).

Statistical analyses

We examined the prevalence of meeting our claims-based definition of precancer depression or precancer anxiety as well as CA-depression or CA-anxiety. We performed univariate analyses to determine covariates associated with either CA-depression or CA-anxiety. Differences in demographic variables between groups were evaluated using χ-squared tests. Next, multivariate logistic regression models were fit to characterize factors independently associated with these 2 outcomes. Based on existing literature,9,12,14 we adjusted for potential confounders: age, sex, race, marital status, income, education, and comorbidity in the multivariate models regardless of univariate significance. We also adjusted for additional variables that were significant with P < .05 in univariate analysis. Of note, since CA-depression was mutually exclusive with precancer depression, univariate and multivariate analyses examining the outcome of CA-depression excluded individuals with precancer depression given that they already had depression and were thus unable to develop CA-depression. Analyses examining CA-anxiety excluded individuals with precancer anxiety for the same rationale.

We conducted 2 sensitivity analyses. First, we conducted an analysis in which the timeframe of assessing the prevalence of precancer depression and precancer anxiety was 24 months to 6 months prior to blood cancer diagnosis. The rationale was to assess for the possibility of blood cancer symptoms being conflated with a diagnosis of precancer depression or precancer anxiety. Second, we conducted multivariable analyses to assess factors associated with CA-depression or CA-anxiety, in which we expanded the definition of these outcomes to encompass up to 6 months after blood cancer diagnosis. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 and R (Version 4.0.3).

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 75 691 patients diagnosed with hematologic malignancies between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2015. The median age at diagnosis was 78 years (interquartile range: 72-83 years), with 40.9% of the cohort ≥80 years old. Approximately half of the cohort was female (51.6%) and married (51.4%). The majority of the cohort was White (89.3%). Table 1 displays other patient characteristics.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic . | Total n = 75 691n, (%) . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| Lymphoma | 47 043 (62.2) |

| Myeloma | 13 057 (17.3) |

| Leukemia | 8 689 (11.5) |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 6 902 (9.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 664 (48.4) |

| Female | 39 027 (51.6) |

| Age (ys) | |

| 67-69 | 8 884 (11.7) |

| 70-74 | 17 325 (22.9) |

| 75-79 | 18 553 (24.5) |

| ≥80 | 30 929 (40.9) |

| Race | |

| White | 67 558 (89.3) |

| Non-White | 8 133 (10.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 72 089 (95.2) |

| Hispanic | 3 602 (4.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 38 869 (51.4) |

| Not married | 36 822 (48.6) |

| Residency | |

| Urban | 74 079 (97.9) |

| Rural | 1 612 (2.1) |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |

| 1 (lowest) | 16 361 (21.6) |

| 2 | 14 855 (19.6) |

| 3 | 14 777 (19.5) |

| 4 | 14 833 (19.6) |

| 5 (highest) | 14 865 (19.6) |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |

| 1 (lowest) | 15 587 (20.6) |

| 2 | 14 688 (19.4) |

| 3 | 14 879 (19.7) |

| 4 | 14 989 (19.8) |

| 5 (highest) | 15 548 (20.5) |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |

| Midwest | 9 996 (13.2) |

| Northeast | 18 898 (25.0) |

| South | 18 183 (24.0) |

| West | 28 614 (37.8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | 37 979 (50.2) |

| 1 | 18 166 (24.0) |

| 2+ | 19 546 (25.8) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 2000-2003 | 17 864 (23.6) |

| 2004-2007 | 19 835 (26.2) |

| 2008-2011 | 19 386 (25.6) |

| 2012-2015 | 18 606 (24.6) |

| Characteristic . | Total n = 75 691n, (%) . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |

| Lymphoma | 47 043 (62.2) |

| Myeloma | 13 057 (17.3) |

| Leukemia | 8 689 (11.5) |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 6 902 (9.1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 664 (48.4) |

| Female | 39 027 (51.6) |

| Age (ys) | |

| 67-69 | 8 884 (11.7) |

| 70-74 | 17 325 (22.9) |

| 75-79 | 18 553 (24.5) |

| ≥80 | 30 929 (40.9) |

| Race | |

| White | 67 558 (89.3) |

| Non-White | 8 133 (10.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 72 089 (95.2) |

| Hispanic | 3 602 (4.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 38 869 (51.4) |

| Not married | 36 822 (48.6) |

| Residency | |

| Urban | 74 079 (97.9) |

| Rural | 1 612 (2.1) |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |

| 1 (lowest) | 16 361 (21.6) |

| 2 | 14 855 (19.6) |

| 3 | 14 777 (19.5) |

| 4 | 14 833 (19.6) |

| 5 (highest) | 14 865 (19.6) |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |

| 1 (lowest) | 15 587 (20.6) |

| 2 | 14 688 (19.4) |

| 3 | 14 879 (19.7) |

| 4 | 14 989 (19.8) |

| 5 (highest) | 15 548 (20.5) |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |

| Midwest | 9 996 (13.2) |

| Northeast | 18 898 (25.0) |

| South | 18 183 (24.0) |

| West | 28 614 (37.8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | 37 979 (50.2) |

| 1 | 18 166 (24.0) |

| 2+ | 19 546 (25.8) |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 2000-2003 | 17 864 (23.6) |

| 2004-2007 | 19 835 (26.2) |

| 2008-2011 | 19 386 (25.6) |

| 2012-2015 | 18 606 (24.6) |

Quintiles based on percentage of individuals 25 yrs and older with some college education in a census tract.

Quintiles based on the median household or per capita income within each census tract.

Depression and anxiety outcomes

Overall, 14 056 patients (18.6%) in this cohort met our claims-based criteria for at least 1 of the mental health disorders of interest. Of the total cohort, 13.7% had precancer depression and/or precancer anxiety, while 4.9% had CA-depression or CA-anxiety. Specifically, 4891 patients (6.5%) met the criteria for precancer depression without concurrent precancer anxiety, 3258 patients (4.3%) met the criteria for precancer anxiety without concurrent precancer depression, and 2190 patients (2.9%) met the criteria for both precancer depression and precancer anxiety. In our cohort, 2092 patients (2.8%) met the criteria for CA-depression, while 1586 patients (2.1%) met the criteria for CA-anxiety. Prevalence of precancer depression and/or precancer anxiety remained similar in sensitivity analysis that captured claims from 24 months to 6 months prior to blood cancer diagnosis (11.5%).

CA-depression.

A total of 2092 patients met our claims-based definition of CA-depression without having concurrent CA-anxiety. In univariate analysis, patients with CA-depression were more likely to have had precancer anxiety (13.1% vs 4.5%, P < .001), be female (56.9% vs 49.7%, P < .001), not be married (54.4% vs 47.4%, P < .001), have a higher comorbidity index (32.0% vs 24.4%, P < .001), and have myeloma (21.9% vs 17.2%, P < .001) when compared with individuals without CA-depression (Table 2).

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with CA-depression

| Characteristic . | CA-depression present n = 2092 n (%) . | CA-depression absent n = 66 518 n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Lymphoma | 1223 (58.5) | 41 470 (62.3) | <.001 |

| Myeloma | 458 (21.9) | 11 448 (17.2) | |

| Leukemia | 241 (11.5) | 7 665 (11.5) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 170 (8.1) | 5 935 (8.9) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 902 (43.1) | 33 436 (50.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 1190 (56.9) | 33 082 (49.7) | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 67-69 | 219 (10.5) | 7 889 (11.9) | .006 |

| 70-74 | 460 (22.0) | 15 369 (23.1) | |

| 75-79 | 490 (23.4) | 16 370 (24.6) | |

| ≥80 | 923 (44.1) | 26 890 (40.4) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 1886 (90.2) | 59 167 (88.9) | .090 |

| Non-White | 206 (9.8) | 7 351 (11.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 954 (45.6) | 34 984 (52.6) | <.001 |

| Not married | 1138 (54.4) | 31 534 (47.4) | |

| Residency | |||

| Urban | 2053 (98.1) | 65 085 (97.8) | .409 |

| Rural | 39 (1.9) | 1 433 (2.2) | |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 471 (22.5) | 14 442 (21.7) | .448 |

| 2 | 388 (18.5) | 13 121 (19.7) | |

| 3 | 403 (19.3) | 13 031 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 431 (20.6) | 12 944 (19.5) | |

| 5 (highest) | 399 (19.1) | 12 980 (19.5) | |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 471 (22.5) | 13 570 (20.4) | .031 |

| 2 | 429 (20.5) | 12 778 (19.2) | |

| 3 | 392 (18.7) | 13 065 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 401 (19.2) | 13 257 (19.9) | |

| 5 (highest) | 399 (19.1) | 13 848 (20.8) | |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |||

| Midwest | 347 (16.6) | 8 673 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 458 (21.9) | 17 098 (25.7) | |

| South | 517 (24.7) | 15 747 (23.7) | |

| West | 770 (36.8) | 25 000 (37.6) | |

| Year of cancer diagnosis | |||

| 2000-2003 | 516 (24.7) | 15 859 (23.8) | .810 |

| 2004-2007 | 547 (26.1) | 17 496 (26.3) | |

| 2008-2011 | 536 (25.6) | 17 045 (25.6) | |

| 2012-2015 | 493 (23.6) | 16 118 (24.2) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 909 (43.5) | 34 473 (51.8) | <.001 |

| 1 | 514 (24.6) | 15 837 (23.8) | |

| 2+ | 669 (32.0) | 16 208 (24.4) | |

| Precancer anxiety | |||

| Absent | 1817 (86.9) | 63 535 (95.5) | <.001 |

| Present | 275 (13.1) | 2 983 (4.5) |

| Characteristic . | CA-depression present n = 2092 n (%) . | CA-depression absent n = 66 518 n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Lymphoma | 1223 (58.5) | 41 470 (62.3) | <.001 |

| Myeloma | 458 (21.9) | 11 448 (17.2) | |

| Leukemia | 241 (11.5) | 7 665 (11.5) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 170 (8.1) | 5 935 (8.9) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 902 (43.1) | 33 436 (50.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 1190 (56.9) | 33 082 (49.7) | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 67-69 | 219 (10.5) | 7 889 (11.9) | .006 |

| 70-74 | 460 (22.0) | 15 369 (23.1) | |

| 75-79 | 490 (23.4) | 16 370 (24.6) | |

| ≥80 | 923 (44.1) | 26 890 (40.4) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 1886 (90.2) | 59 167 (88.9) | .090 |

| Non-White | 206 (9.8) | 7 351 (11.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 954 (45.6) | 34 984 (52.6) | <.001 |

| Not married | 1138 (54.4) | 31 534 (47.4) | |

| Residency | |||

| Urban | 2053 (98.1) | 65 085 (97.8) | .409 |

| Rural | 39 (1.9) | 1 433 (2.2) | |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 471 (22.5) | 14 442 (21.7) | .448 |

| 2 | 388 (18.5) | 13 121 (19.7) | |

| 3 | 403 (19.3) | 13 031 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 431 (20.6) | 12 944 (19.5) | |

| 5 (highest) | 399 (19.1) | 12 980 (19.5) | |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 471 (22.5) | 13 570 (20.4) | .031 |

| 2 | 429 (20.5) | 12 778 (19.2) | |

| 3 | 392 (18.7) | 13 065 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 401 (19.2) | 13 257 (19.9) | |

| 5 (highest) | 399 (19.1) | 13 848 (20.8) | |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |||

| Midwest | 347 (16.6) | 8 673 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 458 (21.9) | 17 098 (25.7) | |

| South | 517 (24.7) | 15 747 (23.7) | |

| West | 770 (36.8) | 25 000 (37.6) | |

| Year of cancer diagnosis | |||

| 2000-2003 | 516 (24.7) | 15 859 (23.8) | .810 |

| 2004-2007 | 547 (26.1) | 17 496 (26.3) | |

| 2008-2011 | 536 (25.6) | 17 045 (25.6) | |

| 2012-2015 | 493 (23.6) | 16 118 (24.2) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 909 (43.5) | 34 473 (51.8) | <.001 |

| 1 | 514 (24.6) | 15 837 (23.8) | |

| 2+ | 669 (32.0) | 16 208 (24.4) | |

| Precancer anxiety | |||

| Absent | 1817 (86.9) | 63 535 (95.5) | <.001 |

| Present | 275 (13.1) | 2 983 (4.5) |

See Table 1 footnotes.

In multivariate analysis (Table 3), precancer anxiety remained significantly associated with developing CA-depression (odds ratio [OR] 2.98; 95% CI 2.61-3.41). Other factors associated with higher odds of developing CA-depression included female sex (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.09-1.31), nonmarried status (OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.10-1.33), higher comorbidity scores (score of 2+ vs 0; OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.39-1.71), and myeloma diagnosis (OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.22-1.52) with lymphoma as the referent disease. Non-White race conferred decreased odds of developing CA-depression (OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.69-0.93). Findings of our multivariate analysis were similar in sensitivity analyses in which CA-depression was assessed up to 6 months following blood cancer diagnosis (supplemental Table 2).

Multivariate analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with CA-depression

| Characteristic . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | |

| Female | 1.20 | 1.09-1.31 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lymphoma | Ref | |

| Myeloma | 1.36 | 1.22-1.52 |

| Leukemia | 1.08 | 0.94-1.24 |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 0.89 | 0.75-1.04 |

| Age (y) | ||

| 67-69 | Ref | |

| 70-74 | 1.06 | 0.90-1.25 |

| 75-79 | 1.02 | 0.87-1.20 |

| ≥80 | 1.10 | 0.94-1.28 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Ref | |

| Not married | 1.21 | 1.10-1.33 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Non-White | 0.80 | 0.69-0.93 |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.87 | 0.76-1.00 |

| 3 | 0.88 | 0.76-1.01 |

| 4 | 0.89 | 0.77-1.04 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.84 | 0.71-0.98 |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.87-1.15 |

| 3 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.06 |

| 4 | 0.98 | 0.84-1.13 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.94 | 0.81-1.09 |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | ||

| Midwest | Ref | |

| Northeast | 0.64 | 0.55-0.75 |

| South | 0.76 | 0.66-0.88 |

| West | 0.79 | 0.69-0.90 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 1.21 | 1.09-1.35 |

| 2+ | 1.54 | 1.39-1.71 |

| Precancer anxiety | ||

| Absent | Ref | |

| Present | 2.98 | 2.61-3.41 |

| Characteristic . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | |

| Female | 1.20 | 1.09-1.31 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lymphoma | Ref | |

| Myeloma | 1.36 | 1.22-1.52 |

| Leukemia | 1.08 | 0.94-1.24 |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 0.89 | 0.75-1.04 |

| Age (y) | ||

| 67-69 | Ref | |

| 70-74 | 1.06 | 0.90-1.25 |

| 75-79 | 1.02 | 0.87-1.20 |

| ≥80 | 1.10 | 0.94-1.28 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Ref | |

| Not married | 1.21 | 1.10-1.33 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Non-White | 0.80 | 0.69-0.93 |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.87 | 0.76-1.00 |

| 3 | 0.88 | 0.76-1.01 |

| 4 | 0.89 | 0.77-1.04 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.84 | 0.71-0.98 |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.87-1.15 |

| 3 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.06 |

| 4 | 0.98 | 0.84-1.13 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.94 | 0.81-1.09 |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | ||

| Midwest | Ref | |

| Northeast | 0.64 | 0.55-0.75 |

| South | 0.76 | 0.66-0.88 |

| West | 0.79 | 0.69-0.90 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 1.21 | 1.09-1.35 |

| 2+ | 1.54 | 1.39-1.71 |

| Precancer anxiety | ||

| Absent | Ref | |

| Present | 2.98 | 2.61-3.41 |

See Table 1 footnotes.

CA-anxiety.

A total of 1586 patients met our claims-based definition of CA-anxiety without having concurrent CA-depression. In univariate analysis, patients with CA-anxiety were more likely to have had precancer depression (18.2% vs 6.7%, P < .001), be female (67.8% vs 49.7%, P < .001), be White (91.9% vs 89.0%, P < .001), not be married (51.0% vs 47.9%, P = .016) when compared with individuals without CA-anxiety (Table 4). They were also more likely to have myeloma (19.5% vs 17.2%, P < .001) and less likely to have myelodysplastic syndromes (6.2% vs 9.1%, P < .001).

Univariate analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with CA-anxiety

| Characteristic . | CA-anxiety present n = 1586 n (%) . | CA-anxiety absent n = 68 657 n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 511 (32.2) | 34 527 (50.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 1075 (67.8) | 34 130 (49.7) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Lymphoma | 990 (62.4) | 42 659 (62.1) | <.001 |

| Myeloma | 309 (19.5) | 11 834 (17.2) | |

| Leukemia | 189 (11.9) | 7 915 (11.5) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 98 (6.2) | 6 249 (9.1) | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 67-69 | 217 (13.7) | 8 038 (11.7) | <.001 |

| 70-74 | 428 (27.0) | 15 695 (22.9) | |

| 75-79 | 378 (23.8) | 16 841 (24.5) | |

| ≥80 | 563 (35.5) | 28 083 (40.9) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 1457 (91.9) | 61 084 (89.0) | <.001 |

| Non-White | 129 (8.1) | 7 573 (11.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 777 (49.0) | 35 749 (52.1) | .016 |

| Not married | 809 (51.0) | 32 908 (47.9) | |

| Residency | |||

| Urban | 1547 (97.5) | 67 213 (97.9) | .376 |

| Rural | 39 (2.5) | 1 444 (2.1) | |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 331 (20.9) | 14 932 (21.7) | .142 |

| 2 | 285 (18.0) | 13 493 (19.7) | |

| 3 | 302 (19.0) | 13 411 (19.5) | |

| 4 | 341 (21.5) | 13 459 (19.6) | |

| 5 (highest) | 327 (20.6) | 13 362 (19.5) | |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 373 (23.5) | 13 950 (20.3) | .002 |

| 2 | 323 (20.4) | 13 280 (19.3) | |

| 3 | 316 (19.9) | 13 451 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 292 (18.4) | 13 722 (20.0) | |

| 5 (highest) | 282 (17.8) | 14 254 (20.8) | |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |||

| Midwest | 195 (12.3) | 9 105 (13.3) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 288 (18.2) | 17 500 (25.5) | |

| South | 501 (31.6) | 16 058 (23.4) | |

| West | 602 (38.0) | 25 994 (37.9) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2000-2003 | 267 (16.8) | 16 639 (24.2) | <.001 |

| 2004-2007 | 344 (21.7) | 18 180 (26.5) | |

| 2008-2011 | 430 (27.1) | 17 490 (25.5) | |

| 2012-2015 | 545 (34.4) | 16 348 (23.8) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 797 (50.3) | 34 899 (50.8) | .662 |

| 1 | 393 (24.8) | 16 340 (23.8) | |

| 2+ | 396 (25.0) | 17 418 (25.4) | |

| Precancer depression | |||

| Absent | 1297 (81.8) | 64 055 (93.3) | <.001 |

| Present | 289 (18.2) | 4 602 (6.7) |

| Characteristic . | CA-anxiety present n = 1586 n (%) . | CA-anxiety absent n = 68 657 n (%) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 511 (32.2) | 34 527 (50.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 1075 (67.8) | 34 130 (49.7) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Lymphoma | 990 (62.4) | 42 659 (62.1) | <.001 |

| Myeloma | 309 (19.5) | 11 834 (17.2) | |

| Leukemia | 189 (11.9) | 7 915 (11.5) | |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 98 (6.2) | 6 249 (9.1) | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 67-69 | 217 (13.7) | 8 038 (11.7) | <.001 |

| 70-74 | 428 (27.0) | 15 695 (22.9) | |

| 75-79 | 378 (23.8) | 16 841 (24.5) | |

| ≥80 | 563 (35.5) | 28 083 (40.9) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 1457 (91.9) | 61 084 (89.0) | <.001 |

| Non-White | 129 (8.1) | 7 573 (11.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 777 (49.0) | 35 749 (52.1) | .016 |

| Not married | 809 (51.0) | 32 908 (47.9) | |

| Residency | |||

| Urban | 1547 (97.5) | 67 213 (97.9) | .376 |

| Rural | 39 (2.5) | 1 444 (2.1) | |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 331 (20.9) | 14 932 (21.7) | .142 |

| 2 | 285 (18.0) | 13 493 (19.7) | |

| 3 | 302 (19.0) | 13 411 (19.5) | |

| 4 | 341 (21.5) | 13 459 (19.6) | |

| 5 (highest) | 327 (20.6) | 13 362 (19.5) | |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 373 (23.5) | 13 950 (20.3) | .002 |

| 2 | 323 (20.4) | 13 280 (19.3) | |

| 3 | 316 (19.9) | 13 451 (19.6) | |

| 4 | 292 (18.4) | 13 722 (20.0) | |

| 5 (highest) | 282 (17.8) | 14 254 (20.8) | |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | |||

| Midwest | 195 (12.3) | 9 105 (13.3) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 288 (18.2) | 17 500 (25.5) | |

| South | 501 (31.6) | 16 058 (23.4) | |

| West | 602 (38.0) | 25 994 (37.9) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2000-2003 | 267 (16.8) | 16 639 (24.2) | <.001 |

| 2004-2007 | 344 (21.7) | 18 180 (26.5) | |

| 2008-2011 | 430 (27.1) | 17 490 (25.5) | |

| 2012-2015 | 545 (34.4) | 16 348 (23.8) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 797 (50.3) | 34 899 (50.8) | .662 |

| 1 | 393 (24.8) | 16 340 (23.8) | |

| 2+ | 396 (25.0) | 17 418 (25.4) | |

| Precancer depression | |||

| Absent | 1297 (81.8) | 64 055 (93.3) | <.001 |

| Present | 289 (18.2) | 4 602 (6.7) |

See Table 1 footnotes.

In multivariate analysis (Table 5), precancer depression remained significantly associated with developing CA-anxiety (OR 3.01; 95% CI 2.63-3.44). Female sex (OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.90-2.37) and having a myeloma diagnosis (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.04-1.35) with lymphoma as the referent disease were also significantly associated with CA-anxiety. A diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.56-0.86) with lymphoma as the referent disease and non-White race conferred decreased odds of developing CA-anxiety (OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.52-0.75). Findings of our multivariate analysis were similar to sensitivity analyses in which CA-anxiety was assessed up to 6 months following blood cancer diagnosis (supplemental Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of sociodemographic factors associated with CA-anxiety

| Characteristic . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | |

| Female | 2.12 | 1.90-2.37 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lymphoma | Ref | |

| Myeloma | 1.18 | 1.04-1.35 |

| Leukemia | 1.10 | 0.94-1.29 |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 0.70 | 0.56-0.86 |

| Age | ||

| 67-69 | Ref | |

| 70-74 | 1.03 | 0.87-1.22 |

| 75-79 | 0.86 | 0.72-1.02 |

| ≥80 | 0.74 | 0.63-0.87 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Ref | |

| Not married/other | 0.97 | 0.87-1.08 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Non-White | 0.62 | 0.52-0.75 |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.91 | 0.77-1.07 |

| 3 | 0.97 | 0.82-1.14 |

| 4 | 1.08 | 0.91-1.27 |

| 5 (highest) | 1.01 | 0.85-1.21 |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.08 |

| 3 | 0.90 | 0.77-1.06 |

| 4 | 0.87 | 0.73-1.02 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.83 | 0.70-0.99 |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | ||

| Midwest | Ref | |

| Northeast | 0.85 | 0.70-1.04 |

| South | 1.43 | 1.20-1.70 |

| West | 1.12 | 0.95-1.33 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 1.03 | 0.91-1.17 |

| 2+ | 0.96 | 0.84-1.08 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2000-2003 | Ref | |

| 2004-2007 | 1.22 | 1.03-1.43 |

| 2008-2011 | 1.59 | 1.36-1.85 |

| 2012-2015 | 2.10 | 1.80-2.44 |

| Precancer depression | ||

| Absent | Ref | |

| Present | 3.01 | 2.63-3.44 |

| Characteristic . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | |

| Female | 2.12 | 1.90-2.37 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lymphoma | Ref | |

| Myeloma | 1.18 | 1.04-1.35 |

| Leukemia | 1.10 | 0.94-1.29 |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | 0.70 | 0.56-0.86 |

| Age | ||

| 67-69 | Ref | |

| 70-74 | 1.03 | 0.87-1.22 |

| 75-79 | 0.86 | 0.72-1.02 |

| ≥80 | 0.74 | 0.63-0.87 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Ref | |

| Not married/other | 0.97 | 0.87-1.08 |

| Race | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Non-White | 0.62 | 0.52-0.75 |

| Education (census tract quintile)* | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.91 | 0.77-1.07 |

| 3 | 0.97 | 0.82-1.14 |

| 4 | 1.08 | 0.91-1.27 |

| 5 (highest) | 1.01 | 0.85-1.21 |

| Median income (census tract quintile)† | ||

| 1 (lowest) | Ref | |

| 2 | 0.92 | 0.79-1.08 |

| 3 | 0.90 | 0.77-1.06 |

| 4 | 0.87 | 0.73-1.02 |

| 5 (highest) | 0.83 | 0.70-0.99 |

| Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry region | ||

| Midwest | Ref | |

| Northeast | 0.85 | 0.70-1.04 |

| South | 1.43 | 1.20-1.70 |

| West | 1.12 | 0.95-1.33 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | Ref | |

| 1 | 1.03 | 0.91-1.17 |

| 2+ | 0.96 | 0.84-1.08 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2000-2003 | Ref | |

| 2004-2007 | 1.22 | 1.03-1.43 |

| 2008-2011 | 1.59 | 1.36-1.85 |

| 2012-2015 | 2.10 | 1.80-2.44 |

| Precancer depression | ||

| Absent | Ref | |

| Present | 3.01 | 2.63-3.44 |

See Table 1 footnotes.

Discussion

In this large cohort of older patients with hematologic malignancies, nearly 1 in 5 individuals suffered from depression or anxiety either before their blood cancer diagnosis or as a new diagnosis during the 3 months afterward. Several demographic and clinical factors were significantly associated with developing CA-depression or CA-anxiety, including sex, race, comorbidity, type of blood cancer, and precancer depression or precancer anxiety. Of these factors, having precancer depression or precancer anxiety was associated with the highest odds of developing either CA-anxiety or CA-depression. Taken together, our data suggest a critical need for systematic mental health screening and management for patients with hematologic malignancies.

The prevalence of depression observed in our study is similar to the rates demonstrated in SEER-Medicare studies of patients with solid malignancies such as breast cancer,23 prostate cancer,12 and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.24 On the other hand, the prevalence observed in our analysis is lower when compared with rates of depression and anxiety described in prospective cohorts of blood cancer patients.16,17,25 A potential explanation for this difference is the varying methods used to ascertain depression and anxiety. Unlike our analysis that relied on claims data, which have strong specificity (but lower sensitivity) to determine the disorders of interest, studies with higher rates assessed these disorders using patient-administered questionnaires (eg, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale26 ), which have high sensitivity. Additionally, some studies focused exclusively on hospitalized patients,16,25 and consequently may have captured a subgroup particularly susceptible to developing depressive and anxiety symptoms. Despite the differences in prevalence rates in our analysis and some prior studies, a unifying theme is the considerable burden of depression and anxiety among patients with blood cancers. Prospective systematic efforts to screen for depression and anxiety in all patients with hematologic malignancies are therefore warranted.

Depression and anxiety not only impair QOL,3-5 but also result in worse survival despite state-of-the-art cancer-directed treatments.10,12,27 Given the significant adverse effects of these disorders, our finding of a prevalence rate of 19% is substantial. Mitigating the negative impact of depression and anxiety on patients requires incorporating high-quality psychosocial care with biomedical care. Unfortunately, psychosocial care has mostly lagged behind biomedical care, with existing studies suggesting that a large proportion of oncologists do not routinely screen their patients for distress or mental health disorders.28 In a national survey of 448 oncologists, only 14.3% reported screening for psychosocial distress with validated instruments.28 This is in contrast to robust screening practices in biomedical care; for example, cardiovascular screening is routine for patients with cancer who plan to receive anthracycline-based therapy.29 Our findings in the context of existing literature thus suggest a pressing need for greater attention to psychosocial care for patients with hematologic malignancies. A first step is to promote universal and systematic mental health screening for patients at the time of blood cancer diagnosis.

Although most cases of depression and anxiety were diagnosed before the onset of a blood cancer diagnosis, approximately 4.9% of patients developed depression or anxiety within 3 months of their diagnosis. This suggests that a blood cancer diagnosis itself may contribute to the development of or unmask underlying mental health disorders. Knowledge that one has a blood cancer, the associated symptoms, and uncertainty about the future could increase the risk of depression and anxiety in previously unaffected individuals. Prior research has shown that patients are especially vulnerable to mental health disorders when initially diagnosed with cancer, with over 50% of depression diagnoses during the cancer trajectory occurring in the first 3 months after diagnosis.30 Consequently, in addition to the necessity of screening for depression and anxiety at blood cancer diagnosis, it is also important to employ screening strategies that go beyond a 1-time assessment to multiple assessments concentrated during the 3 months postdiagnosis to identify individuals who may develop new and unmet psychosocial needs.

The fact that precancer anxiety and precancer depression each conferred approximately 3 times higher odds of developing CA-depression and CA-anxiety, respectively, has important clinical implications. First, robust psychosocial support systems are necessary to prevent worsening of already existing mental disorders in this population. Potential ways to do this include close collaboration with patients’ existing psychosocial care providers, engagement with cancer-specific psychosocial resources, and palliative care.31 Second, interventions to prevent new mental health disorders are needed. Existing data illustrate that psychological interventions (eg, relaxation techniques, cognitive behavioral therapy) can prevent the development of depression and anxiety in patients with cancer.32,33

We found factors associated with developing depression and anxiety, such as female sex and higher comorbidity, are consistent with prior literature.13,17,34 The association observed between non-White race and lower rates of CA-depression and CA-anxiety is interesting. The literature on the relationship between race and depression and anxiety is mixed: some retrospective claims-based studies show lower rates of these disorders among non-White patients,13,30 while a prospective study that employed universal mental health screening found greater rates of psychological distress and depression in this group of patients.14 We posit that the lower rates observed are due to inadequate screening by clinicians and reluctance of patients to disclose depression and anxiety symptoms due to stigma concerns.14,35,36 Further research into the relationship between race and mental health disorders is warranted in order to develop culturally responsive psychosocial interventions.

Our study has limitations. First, we used billing claims as a proxy for depression and anxiety diagnoses. The use of billing claims has been shown to have high specificity but low sensitivity, which likely underestimates the true rates of these disorders. Individuals with mild or moderate symptoms of depression/anxiety or those who did not explicitly self-report these symptoms may have been missed by clinicians and thus not captured in billing claims. Additionally, although claims-based data have been used in numerous studies examining mental health disorders in patients with cancer,9,10,12 the specificity and sensitivity of this methodology were validated in a primary care population.19 Oncologists may be less likely to bill for depression and anxiety, which could further underestimate the rates of CA-depression/CA-anxiety observed in our analysis. Our findings should therefore be interpreted in this context. Second, our reliance on an administrative database precluded our ability to ascertain the strategies hematologic oncologists used to diagnose depression and anxiety. For example, we cannot determine if there were discrepant rates of mental health screening by race. Third, our cohort was restricted to individuals ≥67 years, which may limit generalizability to younger populations. We, however, are reassured that the median age for the hematologic malignancies studied is around 70 years.37 Fourth, use of billing claims data to determine rates of anxiety is a relatively novel approach,7,10 and the sensitivity and specificity have not been compared with psychiatric interviews. Hence, further research to validate claims-based determination of anxiety is needed.

In conclusion, our data suggest that a substantial proportion of patients arrive at a blood cancer diagnosis already suffering from depression or anxiety. The knowledge and symptom burden of having a blood cancer may exacerbate existing depressive and anxiety symptoms and increase vulnerability to the development of new mental health disorders. Universal administration of brief and validated mental health screening measures is necessary to identify affected or at-risk individuals so that psychosocial interventions can be provided. Moreover, prioritizing psychosocial resources for those with precancer depression or anxiety may serve to both alleviate symptoms and reduce the risk of developing comorbid mental health disorders. In sum, universal mental health screening and systematic implementation of psychosocial interventions for patients with blood cancers are essential to achieve high-quality cancer care for the whole patient.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database. Interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

T.M.K. received research support from the American Society of Hematology (HONORS Award). O.O.O. received research support from the NCI (K08-CA218295) and the American Society of Hematology (Scholar Award). L.R. and O.O.O. received support from the NCI (U54 DF/HCC-UMB-CA156732; CA156734).

Authorship

Contribution: T.M.K.,G.A.A., and O.O.O. contributed to the conception and design of the work; T.M.K. and O.O.O. drafted the manuscript; and T.M.K., T.J., C.E.M., L.M., L.R., G.A.A., and O.O.O. provided analysis and interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Oreofe O. Odejide, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: Oreofe_Odejide@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

SEER-Medicare data were used for this analysis. Authors who desire to access the data must contact the National Cancer Institute directly to enter into a data use agreement.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.