Abstract

Background: From 2017 to 2020, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) collaborated with 12 hematology societies in Latin America to adapt the ASH guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Objective: To describe the methods used to adapt the ASH guidelines on venous thromboembolism.

Methods: Each society nominated 1 individual to serve on the guideline panel. The work of the panel was facilitated by the 2 methodologists. The methods team selected 4 of the original VTE guidelines for a first round. To select the most relevant questions, a 2-step prioritization process was conducted through an on-line survey and then through in-person discussion. During an in-person meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from 23 April through 26 April 2018, the panel developed recommendations using the ADOLOPMENT approach. Evidence about health effects from the original guidelines was reused, but important data about resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact in health equity were added.

Results: In the guideline accompanying this paper, Latin American panelists selected 17 questions from an original pool of 49. Of the 17 questions addressed, substantial changes were introduced for 5 recommendations, and remarks were added or modified for 12 recommendations.

Conclusions: By using the evidence from an international guideline, a significant amount of work and time were saved; by adding regional evidence, the final recommendations were tailored to the Latin American context. This experience offers an alternative to develop guidelines relevant to local contexts through a global collaboration.

Introduction

International standards require clinical practice guidelines to be transparent about the evidence that informs recommendations.1,2 American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines are developed using the GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) framework, a system intended to maximize transparency around the criteria that drive each recommendation.3 For many recommendations, the most important criteria are the health effects of interventions (ie, the balance of the most important health benefits and harms, such as prevention of clots vs risk of bleeding). Other criteria considered by ASH guideline panels under the GRADE EtD framework include the values and preferences of patients, resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity.1 The health effects of interventions are likely similar in different individuals across many settings, because important differences in biologic effects are rare.4 However, other criteria may be highly contextual, such as cost or feasibility. The ASH guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE), published in 2018 and 2020 in Blood Advances, were developed for a global audience. However, this aim was limited by practical considerations; to offer sensible recommendations, all panels were instructed to assume the perspective of high-resource settings.5 Therefore, implementation of some of these recommendations may not be straightforward in other contexts and may require additional considerations.

From 2017 to 2020, ASH collaborated with the following 12 hematology societies in Latin America to adapt the ASH guidelines on VTE:

Brazil: Associação Brasileira de Hematología, Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular

Colombia: Asociación Colombiana de Hematología y Oncología

Argentina: Grupo Cooperativo Argentino de Hemostasia y Trombosis

Latin America: Grupo Cooperativo Latinoamericano de Hemostasia y Trombosis

Argentina: Sociedad Argentina de Hematología

Bolivia: Sociedad Boliviana de Hematología y Hemoterapia

Chile: Sociedad Chilena de Hematología

Uruguay: Sociedad de Hematología del Uruguay

Mexico: Sociedad Mexicana de Trombosis y Hemostasia

Panama: Sociedad Panameña de Hematología

Peru: Sociedad Peruana de Hematología

Venezuela: Sociedad Venezolana de Hematología

Organization and oversight

The project was organized and coordinated by ASH. Project oversight was provided by the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee, which reported to the ASH Committee on Quality, and by the executive boards of the Latin American partner societies. ASH appointed and convened the guideline panel, applied conflict-of-interest policies, hosted public comment, and developed agreements with the partner societies for their organizational review, approval, and dissemination of the adapted guidelines.

Under a paid agreement with ASH, a methodology team defined and implemented all other methods for the adaptation effort, including facilitating the guideline panel to use the GRADE ADOLOPMENT approach.6 This team was led by 2 methodologists (I.N. and A.I.) and worked in collaboration with the McMaster University GRADE Centre (H.S., Y.Z.). The methods team also conducted original and updated systematic reviews of available evidence.

Panel selection

Each partner society nominated 1 individual to serve on the guideline panel. This nomination was based on content expertise and conflict-of-interest status (see “Guideline funding and management of conflicts of interest”). ASH staff supported panel appointments and coordinated meetings but had no role in choosing the guideline questions for adaptation or determining the recommendations. Staff and members of the partner Latin American societies also did not have any such role. The McMaster University GRADE Centre recommended methodologists, who were free from conflict of interest, to conduct systematic evidence reviews and facilitate the GRADE ADOLOPMENT process. ASH vetted all nominated individuals, including for conflicts of interest, and formed the panel to include 2 methodologist (I.N. and A.I.) and 12 hematologists from 10 countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panamá, Perú, Uruguay, and Venezuela. One content expert represented each partner society. To keep the same level of participation for all of the societies, there was no panel chair. The work of the panel was facilitated by the 2 methodologists, who led all sessions and discussions but did not participate in decisions regarding the direction or strength of the recommendations.

Panel training

During the first in-person meeting (question prioritization), the methodologists conducted a half-day training workshop. The GRADE methodology used in the original VTE guidelines and the ADOLOPMENT approach were introduced. During the second part of the workshop, panelists simulated the adaptation of a recommendation following the methods introduced with real information about the values and preferences of patients, resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity in Latin America.

Subsequently, and when time allowed it, the methodologists used part of the in-person meetings to conduct follow-up workshops focused on specific methodological aspects, such as calculating effect estimates or rating the confidence of the evidence. The topics for the follow-up workshops were selected by the methods team based on the panelists’ preferences.

Guideline funding and management of conflicts of interest

The source guidelines and these adapted guidelines were wholly funded by ASH, a nonprofit medical specialty society that represents hematologists and the ASH Foundation. ASH did not receive any industry funding to underwrite its support of panel and guideline development.

Members of the guideline panel received travel reimbursement for attendance at in-person meetings but received no other payments. Some researchers who contributed to the systematic evidence reviews received salary or grant support through the McMaster GRADE Centre.

Conflicts of interest of all participants were managed according to ASH policies based on recommendations of the Institute of Medicine2 and the Guidelines International Network.5 Participants disclosed all financial and nonfinancial interests relevant to the guideline topic. ASH staff reviewed the disclosures and made judgments about conflicts. The greatest attention was given to direct financial conflicts with for-profit companies that could be directly affected by the guidelines. In consideration of regional economic factors in Latin America, ASH adjusted its conflict-of-interest policy for this panel to allow direct payments from affected companies to panelists to attend educational meetings only. Four panelists reported allowed direct payments to support travel to educational meetings from companies that could be affected by the guidelines. ASH and the partner societies agreed to manage such travel support through disclosure, and the 4 panelists were allowed to participate without recusing from discussions or voting. None of the researchers who contributed to the systematic evidence reviews or who supported the guideline-development process had any direct financial conflicts with for-profit companies that could be affected by the guidelines.

Selecting questions for adaptation

At the time of initiating the adaptation effort, the original VTE guidelines were at different stages of development. The methods team, together with ASH, decided to select 4 of the original VTE guidelines for a first round of adaptation: Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism7; Anticoagulation Therapy8; Prevention in Surgical Patients9; and Prophylaxis for Medical Patients.10 The selection of these specific guidelines was informed by priorities expressed by the Latin American partner societies and the status and publication timeframes of the source guidelines.

Considering the time and resources available, the methods team estimated that 30 to 40 questions were feasible to adapt. To reasonably cover different aspects of VTE, it was decided that, in the first round of adaptation, half of the questions would be allocated to prevention of VTE, whereas the other half were related to management.

To select the most relevant questions for the Latin American region, the methods team conducted a 2-step prioritization process. First, through an on-line survey, panelists were asked to rate each clinical question using a 9-point scale ranging from not relevant to highly relevant to the Latin American setting. The methods team included 5 signaling questions to guide panelist decisions (Box 1) but asked for only 1 overall rating. Then, the methods team ranked the questions according to their median score and presented them at an in-person half-day meeting. Using the ranking as a starting point, panelists selected the final list of questions to be addressed considering the results of the survey, but also ensuring consistency and comprehensiveness of the guidelines as a whole.

Using existing evidence reviews and inclusion of local data

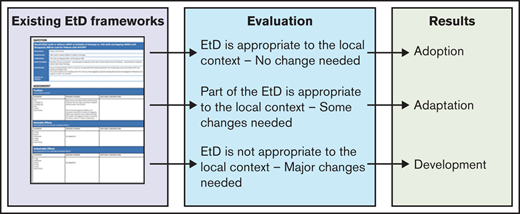

The strengths of the ADOLOPMENT approach reside in the use of existing EtD Frameworks to develop locally relevant recommendations. The detailed methods are described elsewhere.6 In short, the core of the procedure is to evaluate the complete EtD framework, rather than only the recommendation. If the panel considers that the EtD framework is appropriate to the context in which the recommendation will be applied, it may decide to adopt the recommendation without change. Another option is that panelists believe that most of the framework can be reused, but important additional data must be added. In this case, the framework is updated, and an adapted recommendation is developed. Finally, the last option is that panelists believe that the original EtD framework needs major modifications. In this case, the process is conceptually equivalent to developing a new recommendation using GRADE methods (Figure 1). It is important to note that the ADOLOPMENT method is applied at the recommendation level, not to the entire guideline. Thus, it is possible that adoption, adaptation, and development coexist in a particular guideline.

In this case, the methods team and the guideline panel judged that the systematic reviews about health effects from the original guidelines could be reused, but important data about resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity needed to be added to reflect the context of Latin America. Therefore, following the definitions outlined in Figure 1, the methods team and the guideline panel conducted an adaptation of the original guidelines to the Latin American context.

For each of the selected questions, the methods team updated the electronic search of randomized trials and observational studies of the original guidelines (using the same search strategies) and conducted a comprehensive search of regional evidence about patient values and preferences, resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity. Most of the search for regional information was done by hand using the ISPOR Presentations Database (https://www.ispor.org) and LILACS (https://lilacs.bvsalud.org) Web sites. One of the methodologists conducted a search of these Web sites using keywords derived from the electronic search. The results of the electronic and hand searches were combined and reviewed independently by the 2 methodologists. The evidence selection and data extraction were done independently and in duplicate. Disagreements were recorded and resolved by consensus. Finally, guideline panelists were asked to provide any information that they considered relevant.

The data from the original guidelines and the regional information were summarized by the methods team on the EtD framework using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool and its ADOLOPMENT module (www.gradepro.org, McMaster University and Evidence Prime, Inc., Kraków, Poland).

The updated EtD frameworks were circulated among the guideline panelists before the meeting to develop recommendations.

Development of recommendations

During an in-person meeting that took place in Rio de Janeiro from 23 April to 26 April 2018, the panel developed recommendations based on the evidence summarized in the EtD tables.

At the first panel meeting, panelists expressed their preferred language for the discussions. They selected Spanish, because it was the native language for all but 1 of the panelists, who was from Brazil but also was fluent in Spanish. All of the documentation, including evidence and EtDs, was provided in English and Spanish. Methodologists were fluent in English and Spanish, and ASH staff included members who also were fluent in English and Spanish.

The Latin American panelists made judgments on every relevant domain included in the EtDs and then defined the direction and strength of every recommendation. Judgments made in the development of the original VTE guidelines were not considered, and panelists were not aware of those decisions.

The meeting was facilitated by 2 methodologists (I.N. and A.I.) who alternated between leading the discussion and recording the decisions and additional comments on the EtDs. Special emphasis was placed on considering the different scenarios within the region at the moment of making judgments about resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity.

Panelists agreed on each of the EtDs domain by consensus and then on the direction and strength of recommendations through group discussion and deliberation. In rare instances when panelists could not reach universal agreement regarding the EtD judgments or the direction or strength of the recommendation, a vote took place. None of the panelists had conflicts of interests other than travel support; therefore, none were excluded from voting. The direction of the recommendation was decided by a simple majority, whereas an 80% majority was required to issue a strong recommendation.

Additionally, panelists were encouraged to provide remarks that may enhance the usability and implementation of the recommendations within the region.

All of the recommendations were developed in English and were translated into Spanish and Portuguese. The methodologists and panel members reviewed and optimized the accuracy of these translations. Each guideline for Latin America is going to be published with its recommendations in English, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Document review

Draft recommendations were reviewed by all members of the panel, revised, and made available online from 7 March through 12 April 2019 for external review by stakeholders, including members of the Latin American partner societies, allied organizations, medical professionals, patients, and the general public. Notifications were made via e-mail, social media, and at in-person meetings. There were 385 views of the draft recommendations; 78% of views were from Latin America. Five individuals submitted comments. The recommendations were revised to address pertinent comments, but no changes were made to their direction or strength. On 18 December 2020, the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee and the ASH Committee on Quality agreed that the defined guideline-development process was followed; on 6 January 2021, the officers of the ASH Executive Committee approved submission of the guidelines for publication under the imprimatur of ASH. The partner societies approved the guidelines between 12 November and 10 December 2020. The guidelines were then subjected to peer review by Blood Advances.

Results

In the guideline accompanying this paper, Latin American panelists started with a pool of 49 potential clinical questions (28 from the original Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism and 21 from Anticoagulation Therapy). Through the prioritization process, they selected 17 questions that were considered more relevant for the region.

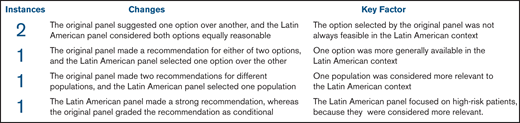

Following the process outlined previously, they made 17 adapted recommendations. Five recommendations changed significantly with respect to the original guidelines (Figure 2).

In 2 instances, the original panel suggested 1 option over another, and the Latin American panel considered that both options were equally reasonable for the Latin American context. The first of these changes occurred with regard to the recommendation about home or hospital treatment in patients with pulmonary embolism and a low risk for complications. The original panel suggested home treatment over hospital treatment; however, offering appropriate home care may not be feasible in many settings within the region. Therefore, hospital treatment was suggested as an equally valid alternative by the Latin American panel. The second of these changes happened with regard to the recommendation about the management of life-threatening bleeding during treatment of VTE. The original panel suggested the use of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrates over fresh-frozen plasma; however, prothrombin complex concentrates are not generally available within the region. Thus, a recommendation in favor of its use would have been difficult to implement. Accordingly, the Latin American panel made a conditional recommendation for prothrombin complex concentrates or fresh-frozen plasma.

In 1 instance, the original panel made a neutral recommendation for 2 options, and the Latin American panel selected 1 of the options over the other. This happened with regard to the recommendation about the dose of Direct Oral Anticoagulants after the initial period of anticoagulation. The original panel made a conditional recommendation for a low or a standard dose, whereas the Latin American panel selected a standard dose. This recommendation was based on the availability of the different formulations within the region, especially when pooled procurement mechanisms are used to enhance affordability.

In 2 instances, the Latin American panel focused the recommendation on a different target population than used by original panel. This occurred with recommendations about the use of indefinite anticoagulation after a thrombotic event. In 1 of these instances, the original panel made 2 recommendations for low- and high-risk groups. The Latin American panel considered the high-risk group more relevant and, hence, issued a recommendation only for this group. The second of these changes occurred with the recommendation about the management of a thrombosis related to a chronic risk factor (eg, tetraplegia). The original panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of indefinite anticoagulation, whereas the Latin American panel made a strong recommendation in the same direction. This change in the strength was based on the fact that the Latin American panel focused on high-risk patients because they were considered more relevant.

Finally, remarks were added (when the original guideline did not provide remarks) to 7 recommendations, and the remarks were significantly modified for 5 recommendations.

Discussion

Despite rigorous methods, many elements of an evidence-based guideline depend on subjective judgments by the panel: Which questions are prioritized and included in the guideline? How do we define the target population? Which evidence do we consider? How do we judge the magnitude of the benefits and harms? How much weight do we give to resources and other considerations? And many others. Even when a guideline group develops recommendations that consider a global audience, explicitly or implicitly in their minds they have a specific setting of reference in which they anchor their judgments. Therefore, when a recommendation is developed, it may not be easily applied in settings not considered by panelists. It is very difficult to make truly global recommendations.

Language is another major barrier for global recommendations. Even with very clear and actionable recommendations, such as those produced when adhering to the GRADE approach, readers and users may misunderstand what guideline developers meant. In the process of translating recommendations, which may occur informally or formally, technical and/or common words may lose part of their meaning. Having a recommendation specifically tailored to a particular setting that, in addition, is in the native language of users probably enhances the usability of the guidelines.

Given the special circumstances of these adapted guidelines, the panel worked without a lead content expert, but 2 methodologists with in-depth internal medicine experience took the lead. Typically, in an ASH guideline, the panel is led by a content expert who is also experienced with guideline development and GRADE methods. Generally, the chair of the panel leads the discussion and writes the recommendations and their remarks. The methods chair typically supports this role and helps to interpret the evidence. In the adapted guidelines, the 2 methods experts led the panel discussions and wrote the recommendations and their remarks. The panel as a whole contributed clinical expertise in the absence of an identified lead content expert. The methodologists facilitated discussions adherent to the development of a guideline; however, they did not participate in the consensus or voting regarding the direction or strength of recommendations. This guideline panel model may be useful when an organization does not want to give prominence to 1 representative over others or when content experts are not experienced in guideline development or GRADE methods.

The ASH approach is to develop guidelines intended for a global audience while facilitating and expediting local adaptation of the recommendations. By sharing and reusing some of the evidence of the original guidelines a significant amount of work is eliminated; by adding regional evidence, the final recommendations were tailored to the Latin American perspective. As our results showed, many important changes were made to the original recommendations in specific ways that may make them more applicable to the Latin American context.

Criteria to inform prioritization of guideline questions

A question would be considered of priority if:

It commonly arises in practice

There is uncertainty in practice with regard to the management of patients

There is new research evidence to consider

It Is associated with variation in practice

It has important consequences for, or is associated with, high resource use or costs

Authorship

Contribution: I.N., H.S., K.E.A, J.C., R.P., R.K., and Y.Z. developed the methods for this adaptation; I.N. and A.I. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript based on author suggestions; and guideline panel members (I.N., A.I., R.A., G.L.B., P.C., C.C.C., M.C.G.E., P.P.G.L., J.P., L.A.M.-G., S.M.R., J.C.S., and M.L.T.V.) critically reviewed the manuscript and provided suggestions for improvement.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: K.E.A., J.C., R.K., and R.P. are employed by ASH, which funded and disseminated the guidelines discussed in this article. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.