Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common disease in Latin American settings. Implementing international guidelines in Latin American settings requires additional considerations.

Objective: The purpose of our study was to provide evidence-based guidelines about managing VTE for Latin American patients, clinicians, and decision makers.

Methods: We used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)-ADOLOPMENT method to adapt recommendations from 2 American Society of Hematology (ASH) VTE guidelines (Treatment of VTE and Anticoagulation Therapy). ASH and local hematology societies formed a guideline panel comprised of medical professionals from 10 countries in Latin America. Panelists prioritized 18 questions relevant for the Latin American context. A knowledge synthesis team updated evidence reviews of health effects conducted for the original ASH guidelines and summarized information about factors specific to the Latin American context (ie, values and preferences, resources, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity).

Results: The panel agreed on 17 recommendations. Compared with the original guideline, 4 recommendations changed direction and 1 changed strength.

Conclusions: This guideline adolopment project highlighted the importance of contextualization of recommendations suggested by the changes to the original recommendations. The panel also identified 2 implementation priorities for the region: expanding the availability of home treatment and increasing the availability of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). The guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of home treatment for individuals with deep venous thrombosis and a conditional recommendation for either home or hospital treatment for individuals with pulmonary embolism. In addition, a conditional recommendation was made in favor of DOACs over vitamin K antagonists for several populations.

Introduction

Aim of these guidelines and specific objectives

The purpose of these guidelines is to provide evidence-based recommendations about the treatment of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) for the Latin American context. The recommendations included in this article were adapted specifically for the Latin American setting from 2 previous guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE) published by the American Society of Hematology (ASH). The target audience includes hematologists, general practitioners, internists, hospitalists, vascular interventionalists, intensivists, other clinicians, pharmacists, patients, and decision makers.

Current evidence-based recommendations are informed by different sources of evidence, such as randomized trials that evaluate the health effects of interventions, and also by studies that assess patients’ values and preferences, use of resources, accessibility, feasibility, and impact in health equity.1-3 Some of these factors are likely to be variable in different settings (eg, costs). Although the ASH Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism were developed for a global audience, recommendations were influenced by the perspectives of high-income countries. Therefore, implementation of some of these recommendations may not be straightforward in other contexts and may require additional considerations. Developing evidence-based recommendations is a lengthy and resource-intensive process, mainly because of the difficulty of identifying and synthesizing the relevant evidence necessary to develop trustworthy recommendations. Thus, the whole process cannot be easily replicated when local recommendations are needed, so adaptation is an efficient approach.

The model we used in this guideline, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)-ADOLOPMENT,4 allowed us to take advantage of the enormous effort made in the development of the original ASH VTE guidelines, and at the same time, to generate recommendations specifically tailored for the Latin American setting.

Description of the health problem

VTE, which includes DVT and PE, is a relatively frequent disease in the Latin American setting. In a cohort of 1138 individuals from Argentina, the incidence of VTE was estimated to be 1.65 per 1000 per year, with a prevalence as high as 5.9 per 1000 per year in older adults.5

The risk of a recurrent VTE event varies according to whether the initial event was associated with an acquired risk factor (referred to as a provoked event) or whether it occurred in the absence of any provoking risk factors (referred to as an unprovoked event). For patients with provoked VTE, the annual risk of recurrence after completing a course of anticoagulant therapy has been estimated to be 4% to 9%,6,7 depending on whether the risk factor continues to be present, whereas the risk of recurrence of an unprovoked VTE after completing anticoagulant therapy is ∼7%6 during the first year and 40% by 10 years.8

An important socioeconomic gap exists in Latin America. Members of lower socioeconomic strata are disadvantaged, because they have less access to medical health care services, medications, and education.9-23 For significant sectors of society, spending on drugs remains the most important component of out-of-pocket expenditure because health care coverage is absent or inadequate.24 In addition, some technologies are not available at some medical centers within the region. In this context, VTE management deserves special consideration because feasibility, affordability, and equity issues should be considered in defining strategies that aim to reduce VTE events and VTE-related mortality.

Time frame of the decisions

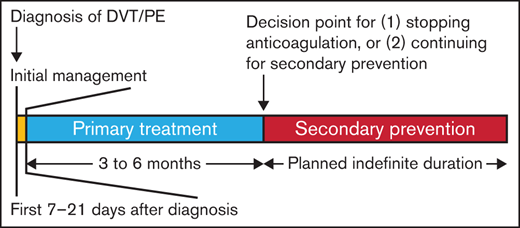

The management of patients with VTE was divided into 3 phases: initial management, which occurs from the time of diagnosis through the first 3 weeks of therapy; primary treatment, which is a time-limited phase that typically runs from 3 weeks to a minimum of 3 months; and secondary prevention (also called prevention of recurrent events or extension therapy), which begins after completion of the primary treatment phase and extends for a prolonged, usually indefinite, period of time (Figure 1).

Time frame of the decisions. Initial management (yellow box) spans the first 1 to 3 weeks after diagnosis of a new vein thromboembolism and includes issues concerning whether the patient can be treated at home or requires admission to the hospital, use of thrombolytic therapy, whether an inferior vena cava filter needs to be placed, and initial anticoagulant therapy. Primary treatment (blue box) continues anticoagulant therapy for 3 to 6 months total and represents the minimal duration of treatment of the VTE. After completion of primary treatment, the next decision concerns whether anticoagulant therapy will be discontinued or whether it will be continued for secondary prevention (red box) of recurrent VTE. Typically, secondary prevention is continued indefinitely, although patients should be reevaluated on a regular basis to review the benefits and risks of continued anticoagulant therapy.

Time frame of the decisions. Initial management (yellow box) spans the first 1 to 3 weeks after diagnosis of a new vein thromboembolism and includes issues concerning whether the patient can be treated at home or requires admission to the hospital, use of thrombolytic therapy, whether an inferior vena cava filter needs to be placed, and initial anticoagulant therapy. Primary treatment (blue box) continues anticoagulant therapy for 3 to 6 months total and represents the minimal duration of treatment of the VTE. After completion of primary treatment, the next decision concerns whether anticoagulant therapy will be discontinued or whether it will be continued for secondary prevention (red box) of recurrent VTE. Typically, secondary prevention is continued indefinitely, although patients should be reevaluated on a regular basis to review the benefits and risks of continued anticoagulant therapy.

Through a prioritization process (see the “Methods” section), the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel focused on recommendations for the initial treatment of VTE and secondary prevention of recurrent VTE events. We also included 3 recommendations regarding optimal management of anticoagulation and antithrombotic therapy in general.

Methods

The recommendations presented in this guideline were adapted to the context of Latin America following the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT method4 and according to the principles outlined by the Institute of Medicine3 and the Guideline International Network.2 The detailed methods used in this effort are described in a companion article.25

Organization, panel composition, planning, and coordination

This project was a collaboration of ASH and 12 hematology societies in Latin America: Associaçáo Brasileira de Hematologia, Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular (ABHH), Asociación Colombiana de Hematología y Oncología (ACHO), Grupo Cooperativo Argentino de Hemostasia y Trombosis (Grupo CAHT), Grupo Cooperativo Latinoamericano de Hemostasia y Trombosis (Grupo CLAHT), Sociedad Argentina de Hematología (SAH), Sociedad Boliviana de Hematología y Hemoterapia (SBHH), Sociedad Chilena de Hematología (SOCHIHEM), Sociedad de Hematología del Uruguay (SHU), Sociedad Mexicana de Trombosis y Hemostasia (SOMETH), Sociedad Panameña de Hematología, Sociedad Peruana de Hematología (SPH), and Sociedad Venezolana de Hematología (SVH). Project coordination was provided by ASH, and project oversight was provided by the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee, which reported to the ASH Committee on Quality, and by the executive boards of the Latin American partner societies. The partner societies nominated individuals to serve on the guideline panel.

The McMaster University GRADE Centre recommended that methodologists conduct systematic evidence reviews and facilitate the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT process. ASH vetted all nominated individuals, including for conflicts of interest, and formed the panel to include 2 methodologists (I.N. and A.I.) and 11 hematologists from 10 countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panamá, Perú, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The partner societies were represented as follows: ABHH, Suely Meireles Rezende; ACHO, Guillermo León Basantes; Grupo CAHT and Grupo CLAHT, Patricia Casais; SAH, Cecilia C. Colorio; SBHH, Mario L. Tejerina Valle; SOCHIHEM, Jaime Pereira; SHU, María Cecilia Guillermo Esposito; Sociedad Panameña de Hematología, Ricardo Aguilar; SPH, Pedro P. García Lázaro; and SVH, Juan Carlos Serrano. In October 2019, representation of Grupo CLAHT was transferred from Patricia Casais to María Cecilia Guillermo Esposito.

The McMaster University GRADE Centre formed a knowledge synthesis team that included individuals based in Chile and Argentina. The team determined methods, prepared meeting materials, updated the evidence reviews conducted for the source ASH guidelines, and searched for regional information about values and preferences, resources, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity. Methodologists from the knowledge synthesis team (I.N. and A.I.) facilitated discussions and guided the panel through decision making.

The panel’s work was done using Web-based tools (www.surveymonkey.com and www.gradepro.org) and face-to-face and online meetings. These meetings were mostly conducted in Spanish. The membership of the panel and the knowledge synthesis team is described in supplement 1.

Guideline funding and management of conflicts of interest

The source guidelines and these adapted guidelines were wholly funded by ASH, a nonprofit medical specialty society that represents hematologists, and the ASH Foundation. ASH staff supported panel appointments and coordinated meetings but had no role in choosing the guideline questions or determining the recommendations. Staff and members of the partner Latin American societies who did not serve on the guideline panel also had no such role.

Members of the guideline panel received travel reimbursement for attending in-person meetings but received no other payments. Through the McMaster GRADE Centre, some researchers who contributed to the systematic evidence reviews received salary or grant support. Other researchers participated to fulfill requirements of an academic degree or program.

Conflicts of interest for all participants were managed according to ASH policies, which are based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (2009) and the Guidelines International Network.26 On appointment, all panelists agreed to avoid direct conflicts of interest with companies that could be affected by the guidelines. Participants disclosed all financial and nonfinancial interests relevant to the guideline topic. ASH staff reviewed the disclosures and made judgments about conflicts. Greatest attention was given to direct financial conflicts with for-profit companies that could be directly affected by the guidelines. At the time these recommendations were made, none of the panelists had such conflicts. In consideration of regional economic factors in Latin America, ASH adjusted the conflict-of-interest policy for this panel to allow direct payment from affected companies to panelists for travel to attend educational meetings only. Four panelists reported travel support to attend educational meetings from companies that could be affected by the guidelines. ASH and the partner societies agreed to manage such support through disclosure. None of the researchers who contributed to the systematic evidence reviews or who supported the guideline development process had any direct financial conflicts with for-profit companies that could be affected by the guidelines. Recusal was not implemented because at the time the recommendations were made, the panel members did not have any direct financial conflicts with companies that could be affected by the guidelines. In August 2020, 1 panelist disclosed that during the guideline development process he received a direct payment from a company that could be affected by the guidelines. This conflict may have triggered recusal at the time the recommendations were made; however, the activity and disclosure occurred after the panel had agreed on recommendations; therefore, the panelist was not recused. Members of the Guideline Oversight Subcommittee reviewed the guidelines in relation to these late disclosures and agreed that conflict was unlikely to have influenced any of the recommendations.

Supplement 2 provides the complete disclosure-of-interest forms for all panel members. In part A of the forms, individuals disclosed direct financial interests for 2 years before appointment; in part B, they disclosed indirect financial interests; and in part C, they disclosed financial interests that were not of main concern. Part D describes new interests disclosed by individuals after appointment. Part E summarizes ASH decisions about which interests were judged to be conflicts and how they were managed. Supplement 3 provides the complete disclosure-of-interest forms for researchers who contributed to these guidelines.

Selecting clinical questions for adaptation

The guideline panel selected the following guidelines to be adapted from the original ASH VTE guidelines: Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism27 and Anticoagulation Therapy.28 This decision was informed by priorities expressed by the Latin American partner societies. The panel also considered the development status and publication time frames of the source guidelines. From all the clinical questions addressed by these 2 source guidelines, the guideline panel prioritized those most relevant for the Latin American setting. First, through an on-line survey, panelists rated the clinical questions using a 9-point scale that ranged from not relevant to highly relevant. Then, clinical questions were ranked on the basis of the median score from all the panelists. Finally, during an in-person meeting, panelists reviewed the scores and selected the final clinical questions on the basis of the results of the survey, and also ensured consistency and comprehensiveness of the guideline as a whole (Table 1).

Clinical questions adapted

| Initial management |

| Home treatment vs hospital treatment in patients with uncomplicated DVT |

| Home treatment vs hospital treatment in patients with PE and low risk of complication |

| DOACs vs VKAs in patients with VTE |

| Thrombolytic therapy plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with extensive proximal DVT |

| Thrombolytic therapy plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with submassive PE |

| Compression stockings plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with DVT and high risk of PTS |

| Secondary prevention: continuation of anticoagulation after primary treatment |

| D-dimer vs no D-dimer to decide duration of treatment in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Prognostic scores vs no prognostic score to decide duration of treatment in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with recurrent unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with VTE related to a chronic risk factor |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with recurrent VTE related to a transient risk factor |

| Aspirin vs anticoagulation in patients with VTE who are going to continue antithrombotic therapy |

| Lower-dose DOACs vs standard-dose DOACs in patients with VTE who are going to continue on anticoagulation |

| DOACs vs LMWH in patients with VTE during treatment with VKAs |

| Additional management issues |

| Continuation of aspirin vs discontinuation in patients VTE who initiate anticoagulation |

| Resumption of oral anticoagulation after an anticoagulation-related major bleeding |

| Four-factor PCCs or FFP in patients with VKA-related life-threatening bleeding |

| Initial management |

| Home treatment vs hospital treatment in patients with uncomplicated DVT |

| Home treatment vs hospital treatment in patients with PE and low risk of complication |

| DOACs vs VKAs in patients with VTE |

| Thrombolytic therapy plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with extensive proximal DVT |

| Thrombolytic therapy plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with submassive PE |

| Compression stockings plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone in patients with DVT and high risk of PTS |

| Secondary prevention: continuation of anticoagulation after primary treatment |

| D-dimer vs no D-dimer to decide duration of treatment in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Prognostic scores vs no prognostic score to decide duration of treatment in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with recurrent unprovoked VTE |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with VTE related to a chronic risk factor |

| Indefinite anticoagulation vs discontinuation in patients with recurrent VTE related to a transient risk factor |

| Aspirin vs anticoagulation in patients with VTE who are going to continue antithrombotic therapy |

| Lower-dose DOACs vs standard-dose DOACs in patients with VTE who are going to continue on anticoagulation |

| DOACs vs LMWH in patients with VTE during treatment with VKAs |

| Additional management issues |

| Continuation of aspirin vs discontinuation in patients VTE who initiate anticoagulation |

| Resumption of oral anticoagulation after an anticoagulation-related major bleeding |

| Four-factor PCCs or FFP in patients with VKA-related life-threatening bleeding |

Evidence review and inclusion of local data

The original ASH VTE guidelines included an Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework for each of the questions addressed.1 The knowledge synthesis team updated the electronic search of randomized trials and observational studies of the original guidelines and conducted a comprehensive search of regional evidence about patients’ values and preferences, resource use, accessibility, feasibility, and impact on health equity (supplement 4). For each EtD framework, researchers for the knowledge synthesis team summarized the data used on the original guideline as well all relevant regional information identified using the GRADEpro guideline development tool (McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, and Evidence Prime, Inc., Kraków, Poland). To estimate the absolute effect of the interventions, we calculated the risk difference by multiplying the pooled risk ratio and the baseline risk of each outcome. As baseline risk, we used the median of the risks observed in control groups of the included trials. When possible, the researchers used the baseline risk observed in large observational studies.

We assessed certainty of the body of evidence (also known as quality of the evidence or confidence in the estimated effects) following the GRADE approach.29,30 We made judgments regarding risk of bias, precision, consistency, directness, and likelihood of publication bias and categorized the certainty in the evidence into 4 levels ranging from very low to high.

Development of recommendations

During an in-person meeting that took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, April 23-26, 2018, the panel developed recommendations based on the evidence summarized in the EtD tables. The panel agreed on the direction and strength of recommendations through group discussion and deliberation. In rare instances, when consensus was not reached, voting took place. In such circumstances, the result of the voting was recorded on the respective EtD table. The direction of the recommendation was decided by simple majority, whereas an 80% majority was required to issue a strong recommendation. Although in the case of the original VTE guidelines, panels defined the direction and strength of every recommendation and made judgments on every relevant domain included in the EtD, Latin American panelists were not aware of those decisions and judgments.

Document review

Draft recommendations were reviewed by all members of the panel, revised, and then made available online from March 7, 2019, through April 12, 2019, for external review by stakeholders, including members of the Latin American partner societies, allied organizations, medical professionals, patients, and the general public. Notifications were made via e-mail and social media and at in-person meetings. There were 385 views of the draft recommendations, 78% of which came from Latin America. Five individuals submitted comments. The document was revised to address pertinent comments, but no changes were made to recommendations. On December 18, 2020, the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee and the ASH Committee on Quality agreed that the defined guideline development process was followed, and on January 6, 2021, the officers of the ASH Executive Committee approved submission of the guidelines for publication under the imprimatur of ASH. Starting on November 12, 2020, and through December 10, 2020, the partner societies approved the guidelines. The guidelines were then subjected to peer review by Blood Advances.

How to use these guidelines

The recommendations are labeled as “strong” or “conditional” according to the GRADE approach. The phrase “the ASH Latin American guideline panel recommends” is used for strong recommendations, and “the ASH Latin American guideline panel suggests” is used for conditional recommendations. Table 1 provides GRADE’s interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations by patients, clinicians, health care policy makers, and researchers.

These guidelines are primarily intended to help clinicians make decisions about diagnostic and treatment alternatives. Other purposes are to inform policy, education, and advocacy and to state future research needs. They may also be used by patients. These guidelines are not intended to serve as or be construed as a standard of care. Clinicians must make decisions on the basis of the clinical presentation of each individual patient, ideally through a shared process that considers the patient’s values and preferences with respect to the anticipated outcomes of the chosen option. Decisions may be constrained by the realities of a specific clinical setting and local resources, including but not limited to institutional policies, time limitations, or availability of treatments. These guidelines may not include all appropriate methods of care for the clinical scenarios described. As science advances and new evidence becomes available, recommendations may become outdated. Following these guidelines cannot guarantee successful outcomes. ASH and the partner societies do not warrant or guarantee any products described in these guidelines.

Statements about the underlying values and preferences as well as qualifying remarks accompanying each recommendation are its integral parts and serve to facilitate more accurate interpretation. They should never be omitted when quoting or translating recommendations from these guidelines. The use of these guidelines is also facilitated by the links to the EtD frameworks and interactive summary of findings tables in each section.

Search results

In our comprehensive search, we did not identify any additional randomized trials that provided additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the interventions of interest, nor did we find studies reporting patients’ values and preferences. We did find information about the cost of the interventions in different countries of the region as well as evidence of accessibility and potential impact on health equity. This information is summarized for each question in the adapted EtD tables (link)

Recommendations

Interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations

The strength of a recommendation is expressed as either strong (“the guideline panel recommends…”) or conditional (“the guideline panel suggests…”), and the interpretation is described in Table 2.31

Interpretation of strong and conditional recommendations

| Implications for: . | Strong recommendation . | Conditional recommendation . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Clinicians | Most individuals should follow the recommended course of action. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individual patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. | Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients, and clinicians must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with the patient’s values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping individuals to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Policy makers | The recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. | Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess whether decision making is appropriate. |

| Researchers | The recommendation is supported by credible research or other convincing judgments that make additional research unlikely to alter the recommendation. On occasion, a strong recommendation is based on low or very low certainty in the evidence. In such instances, further research may provide important information that alters the recommendations. | The recommendation is likely to be strengthened (for future updates or adaptation) by additional research. An evaluation of the conditions and criteria (and the related judgments, research evidence, and additional considerations) that determined the conditional (rather than strong) recommendation will help to identify possible research gaps. |

| Implications for: . | Strong recommendation . | Conditional recommendation . |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Clinicians | Most individuals should follow the recommended course of action. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individual patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. | Different choices will be appropriate for individual patients, and clinicians must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with the patient’s values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping individuals to make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values, and preferences. |

| Policy makers | The recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. | Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess whether decision making is appropriate. |

| Researchers | The recommendation is supported by credible research or other convincing judgments that make additional research unlikely to alter the recommendation. On occasion, a strong recommendation is based on low or very low certainty in the evidence. In such instances, further research may provide important information that alters the recommendations. | The recommendation is likely to be strengthened (for future updates or adaptation) by additional research. An evaluation of the conditions and criteria (and the related judgments, research evidence, and additional considerations) that determined the conditional (rather than strong) recommendation will help to identify possible research gaps. |

Initial management

In patients with DVT, should we suggest home treatment or hospital treatment?

Recommendation 1

In patients with deep vein thrombosis, DVT, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests home treatment over hospital treatment (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁◯◯).

Remarks: This recommendation does not apply to patients who have other conditions that would require hospitalization, have limited or no support at home, cannot afford medications, or have a history of poor compliance. In addition, patients with a limb-threatening DVT, at high risk of bleeding, or requiring intravenous analgesics may also need to start treatment in the hospital.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Hospitalization costs are significant, and home management was found to be cost saving in studies performed in different countries.32-35 Although we found no study specifically conducted in the Latin American setting, the panel considered that home management is probably also cost saving within the region. For significant sectors of society, expenditures on drugs remain the most important component of out-of-pocket expenditure because health care coverage is absent or inadequate.24 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/Kg8_z9WDHYQ.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. With a body of evidence suggesting that home treatment is safe, the panel agreed that key aspects to consider are costs, equity, and feasibility. Although overall costs are probably reduced with home treatment, in some health systems, home treatment is not covered, and patients need to pay out-of-pocket. In this scenario, home treatment may reduce equity. In addition, because of poor socioenvironmental conditions, home treatment may not be always feasible.

Conclusion

Although home treatment is probably appropriate for the majority of patients, some patients may choose hospital treatment. A shared decision-making approach involving a discussion with the patient about the potential benefits, harms, and cost of the alternatives may be a way of implementing this recommendation. Given the potential savings in cost and the scarcity of hospital beds in the region, health systems in Latin America should make efforts to promote home treatment of patients with a low risk of complications.

In patients with PE and a low risk of complications, should we suggest home treatment or hospital treatment?

Recommendation 2

In patients with PE and a low risk of complications, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests using either home treatment or hospital treatment (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks: This recommendation does not apply to patients who have other conditions that would require hospitalization, have limited or no support at home, cannot afford medications, or have a history of poor compliance.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Hospitalization costs are significant, and home management was found to be cost saving in studies performed in different countries.32-35 Although we found no study that was conducted specifically in the Latin American setting, the panel considered that home management is probably also cost saving within the region. For significant sectors of society, expenditures on drugs remain the most important component of out-of-pocket expenditure because health care coverage is absent or inadequate.24 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/70kNdFlpfWI.

Justification

This recommendation changed its direction. The original guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of home treatment, whereas the Latin American guideline panel made a recommendation for either home or hospital treatment. The panel considered that within the region, there are important barriers to providing appropriate home care for individuals with PE. Those barriers include insufficient number of clinicians, inappropriate support from hospitals to patients being treated at home, and cost.

Conclusion

The panel acknowledged that different scenarios coexist within the region. When home treatment can be provided safely, it represents the preferred alternative for the majority of patients. However, when important barriers exist in terms of human or material resources, patients will probably be better off being treated at the hospital. Still, given the potential savings in cost and the scarcity of hospital beds in the region, health systems in Latin America should make efforts to promote home treatment of patients who have a low risk of complications.

Recognizing patients with PE and a low risk of complications is crucial to adequately implement this recommendation. The PE severity index (PESI) model36,37 can be helpful for estimating the risk of complications, although it is important to note that risk models have, at best, a moderate ability to predict patients’ outcomes and therefore do not replace clinical judgment.

In patients with DVT or PE, should we use direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) or vitamin K antagonists (VKAs)?

Recommendation 3

In patients with DVT or PE, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests using DOACs over VKAs (conditional recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: Patients who are well controlled and without complications with a VKA may prefer to stay with the VKA. Alternatively, patients who are initiating anticoagulation may prefer DOACs over the VKA, given the burden of treatment and the potential reduction of bleeding. In addition, DOACs may be a good alternative for situations in which reliable international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring is not feasible or is difficult. The panel emphasizes that patient education regarding the risk of anticoagulation is equally important with DOACs, especially in situations in which close follow-up is difficult.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. We did observe that pricing of DOACs was highly variable within the region, although it was generally less expensive than that in North America (supplemental Appendix 1). In most of the settings, the cost of the drug has to be covered by patients as an out-of-pocket expenditure, given the lack of appropriate insurance.24 Therefore, drug price may limit access for individuals from lower socioeconomic strata. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/kA6qI3lS9O0.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. However, the panel noted that additional implementation issues may need to be considered in the region. Although the cost of the drug may pose a barrier to its use, in Latin America, a significant proportion of patients do not have access to regular follow-up and monitoring of VKAs. This could make physicians reluctant to start anticoagulation in patients who would otherwise benefit. Using DOACs instead of VKAs may facilitate starting anticoagulation and may have a positive impact on health equity.

Conclusion

When DOACs become available and accessible in a particular health care setting, clinicians may consider informing patients that DOACs are a more convenient alternative to VKAs; their use is probably associated with a smaller risk of bleeding, but the differences are generally of small magnitude.

DOACs have recently been added to the Essential Medicine List of Medication of the World Health Organization,38 which signals that they are a priority among the drugs that need to be added by local health systems. Although absolute differences in outcomes that are important to patients (ie, thrombosis and bleeding) are of small magnitude at the individual level, they add up substantially at the population level. DOACs also have stable pharmacokinetics and bioavailability, do not require dose monitoring or strict follow-up, and are generally preferred by patients.39 The current price of DOACs imposes a significant access barrier (supplemental Appendix 1), especially because insurance coverage of medications within the region is deficient.24 However, from the perspective of the health system, it may be less expensive to offer DOACs than to run organized programs to monitor and follow up with patients using VKAs.40,41 In the next 5 years, primary and secondary patents for DOACs will expire, and less expensive generic alternatives will become available. In the meantime, health care systems may use strategies such as pooled procurement to reduce the price of DOACs.

In patients with extensive proximal DVT, should we use thrombolysis in addition to anticoagulation or anticoagulation alone?

Recommendation 4

In patients with extensive proximal DVT, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests against thrombolysis in addition to anticoagulation (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁◯◯).

Remarks: Thrombolysis is reasonable to consider for patients with limb-threatening DVT, patients with severe symptoms who do not improve with anticoagulation alone, and patients with iliofemoral DVT (high risk of postthrombotic syndrome [PTS]) with an average to low risk of bleeding in those who are averse to the possibility of PTS. The final decision regarding whether to provide thrombolysis should consider the baseline risk of having an adverse event, the patient’s values and preferences, and access to experienced care.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/XRPT3FrSgbs.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel considered that in most clinical scenarios, thrombolysis-related harms outweigh its potential benefits. The panel also noted that thrombolytic therapy is not available in the majority of the health care centers where patients with DVT are treated. Thus, even if clinicians and patients consider thrombolytic therapy a reasonable option for a specific clinical circumstance, it may not be feasible to perform it.

Conclusion

Thrombolytics should be considered as an alternative for limb-threatening DVT. However, in some instances, it may be necessary to transfer the patient to a different medical center, because the intervention is not typically available in most centers. In that case, patients and clinicians should weigh the potential benefits of thrombolytic therapy against the potential harms, costs, and inconvenience of being transferred to a different center where insurance coverage conditions may be different.

In patients with PE and ultrasonography or biomarkers compatible with right ventricular dysfunction (RVD), should we use thrombolysis in addition to anticoagulation or anticoagulation alone?

Recommendation 5

In patients with PE and ultrasonography or biomarkers compatible with RVD (submassive PE), the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests against the use of thrombolysis in addition to anticoagulation (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁◯◯).

Remarks: Patients with a high risk of dying because of PE and a low risk of bleeding may benefit from thrombolysis.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/3kQMfYPS43Q.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel considered that for patients with PE and no clinical hemodynamic failure, the harms of thrombolysis outweigh its potential benefits most of the time. The panel also noted that thrombolytic therapy is not available in the majority of the health care centers within the region. Thus, even if clinicians and patients consider thrombolytic therapy a reasonable option for a specific clinical circumstance, it may not be feasible to perform it.

Conclusion

The panel considered that for the majority of individuals with PE and no clinical hemodynamic failure, the use of thrombolytics may lead to more harms than benefits, despite the evidence of subclinical RVD. However, for patients with PE who are at high risk of dying, thrombolytics might be an option as a rescue measure.

Given that thrombolysis is not typically available, transferring the patient to a different medical center may be necessary. In that case, patients and clinicians should weigh the potential benefits of thrombolytic therapy against the potential harms, costs, and inconvenience of being transferred to a different medical center where insurance coverage conditions may be different.

In patients with DVT and a high risk of PTS, should we use compression stockings in addition to anticoagulation or anticoagulation alone?

Recommendation 6

In patients with DVT and a high risk of PTS, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests against using compression stockings in addition to anticoagulation (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Compression stockings are relatively expensive and typically not covered by health insurance. For significant sectors of society, expenditures on drugs remain the most important component of out-of-pocket expenditure because of absent or inadequate health care coverage.24 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/wqiXQCBTwVM.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel considered that the balance between desirable (potential reduction of PTS) and undesirable (cost and burden) consequences of the use of compression stockings is close, even in individuals with high risk of PTS. The high cost and significant burden of using compression stockings, together with the uncertainty regarding its benefits, justified a recommendation against its use.

Conclusion

Although the use of compression stockings is not appropriate for the majority of patients, some might benefit, such as those with significant pain or edema or those at very high risk of PTS. Some clinical variables have been associated with an increased probability of presenting with PTS and can be used to assess its risk: older age, elevated body mass index, preexisting primary vein insufficiency, recurrent ipsilateral thrombosis, and persistent symptoms after 1 month of treatment.42 Barriers to accessing compression stockings within the region, like their high price and limited availability, should be integrated into the discussion with patients in addition to the potential benefits and harms.

Secondary prevention (prevention of recurrent episodes)

In patients with unprovoked DVT or PE, should we use D-dimer or prognostic scores to guide the duration of anticoagulation?

Recommendation 7

In patients with unprovoked DVT or PE, the Latin American Guideline Panel suggests against use of D-dimer or prognostic scores to guide the duration of anticoagulation. Rather, the majority of individuals should be managed according to Recommendation 8 (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁◯◯).

Remarks: D-dimer alone or as part of a prognostic model may be useful for determining the duration of anticoagulation when patients are undecided or when the clinical situation is difficult.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/Ii_M6mQQ8u0 and https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/0yUMJBPzG-Y.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. Although D-dimer levels and prognostic score correlate with the probability of having a recurrent event, their ability to predict clinical outcomes is limited. In addition, D-dimer is not universally available within the region, and its cost may impose access barriers. Given that prognostic scores generally are based on D-dimer results, the same limitations apply to them.

Conclusion

Individuals with unprovoked events have a relatively high risk of recurrence. Therefore, as per Recommendation 8, the panel considered that using indefinite anticoagulation is probably the best alternative for the majority of these patients. However, deciding on long-term anticoagulation can be difficult, because many aspects, such as feasibility, accessibility, and affordability, need to be considered. In addition, thrombosis and bleeding risk may change over time, which in turn may modify the trade-off between benefits and harms, and some patients may be reluctant to receive indefinite anticoagulant treatment. D-dimer and prognostic scores can be useful for providing additional information when the best course of action is not clear. If patients and clinicians decide to use D-dimer or prognostic scores to aid the decision, it is important to consider that their accuracy is best after the suspension of anticoagulation, and therefore, they should not be used while patients are still receiving anticoagulation treatment.43

In patients with an unprovoked DVT or PE, should we use indefinite anticoagulation or discontinue anticoagulation after a period of 3 to 6 months?

Recommendation 8

In patients with an unprovoked DVT or PE, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests maintaining indefinite anticoagulation over discontinuing it after a period of 3 to 6 months (conditional recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: The final decision for maintaining or interrupting anticoagulation after an initial period should consider the individual risk of VTE recurrence, the individual risk of bleeding, costs, access to follow-up and monitoring, and patients’ values and preferences. This recommendation applies to patients with an average risk of bleeding. Clinicians should be aware that bleeding risk may change over time, so the balance between the desirable and undesirable consequences of indefinite anticoagulation should be reassessed periodically.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. We estimated that VTE recurrence after a first unprovoked event was 7.4 events per 100 patient-years.6 Of these, 4.1 events per 100 patient-years correspond to DVT, and 3.3 events per 100 patient-years corresponds to PE (Table 3).43 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/BRGAa8ywtoQ.

Summary of recommendations for secondary prevention of VTE according to the risk of recurrence without indefinite treatment

| Patients with: . | Estimated risk of recurrence (patient-years) . | Proposed treatment . | Specific strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|

| A recurrent unprovoked DVT or PE | DVT: 6.6 per 100 PE: 5.4 per 100 Total VTE: 12 per 100 | After completing an initial treatment of 3 to 6 months, use indefinite anticoagulation (strong Recommendations 10 and 11). | Use anticoagulants instead of aspirin (conditional Recommendation 13). Use DOACs at standard doses rather than lower doses of DOACs or VKAs (conditional Recommendations 3 and 14). If DOACs are not affordable, VKAs remains a good alternative (conditional Recommendation 3). |

| A provoked DVT or PE related to a chronic risk factor | DVT: 5.3 per 100 PE: 4.4 per 100 Total VTE: 9.7 per 100 | ||

| An unprovoked DVT or PE | DVT: 4.1 per 100 PE: 3.3 per 100 Total VTE: 7.4 per 100 | After completing an initial treatment of 3 to 6 months, offer indefinite anticoagulation (conditional Recommendations 9 and 12). | |

| Recurrent provoked DVT or PE | DVT: 3.1 per 100 PE: 2.5 per 100 Total VTE: 5.6 per 100 |

| Patients with: . | Estimated risk of recurrence (patient-years) . | Proposed treatment . | Specific strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|

| A recurrent unprovoked DVT or PE | DVT: 6.6 per 100 PE: 5.4 per 100 Total VTE: 12 per 100 | After completing an initial treatment of 3 to 6 months, use indefinite anticoagulation (strong Recommendations 10 and 11). | Use anticoagulants instead of aspirin (conditional Recommendation 13). Use DOACs at standard doses rather than lower doses of DOACs or VKAs (conditional Recommendations 3 and 14). If DOACs are not affordable, VKAs remains a good alternative (conditional Recommendation 3). |

| A provoked DVT or PE related to a chronic risk factor | DVT: 5.3 per 100 PE: 4.4 per 100 Total VTE: 9.7 per 100 | ||

| An unprovoked DVT or PE | DVT: 4.1 per 100 PE: 3.3 per 100 Total VTE: 7.4 per 100 | After completing an initial treatment of 3 to 6 months, offer indefinite anticoagulation (conditional Recommendations 9 and 12). | |

| Recurrent provoked DVT or PE | DVT: 3.1 per 100 PE: 2.5 per 100 Total VTE: 5.6 per 100 |

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel reviewed the baseline risk of VTE recurrence used to estimate the absolute effect of indefinite treatment and considered it appropriate for the Latin American setting. Although access to indefinite anticoagulation may be limited within the region, the panel considered that the risk of recurrence was sufficiently high to justify providing indefinite anticoagulation. In this regard, the use of DOACs instead of VKAs (Recommendation 3) may facilitate anticoagulation when follow-up is difficult. The panel acknowledges that many patients with unprovoked VTE are not currently receiving indefinite anticoagulation within the region. Thus, this recommendation is of special importance.

Conclusion

Deciding whether to use indefinite anticoagulation can be difficult. Many factors interplay and have to be considered. In typical patients with unprovoked events, the risk of VTE recurrence is high and the risk of bleeding is low; therefore, most patients will be better off with anticoagulants. However, bleeding risk may change over time; thus, clinicians and patients should reassess the trade-off periodically.

In addition, the burden associated with indefinite anticoagulation is variable with the different options: VKAs require strict follow-up and lifestyle modifications, whereas DOACs are less burdensome. Long-term anticoagulation based on DOACs is probably more sustainable than that with VKAs. Therefore, efforts should be made to increase accessibility and affordability of the former in the region.

In patients with a recurrent unprovoked DVT or PE, should we use indefinite anticoagulation or discontinue anticoagulation after a period of 3 to 6 months?

Recommendation 9

In patients with a recurrent unprovoked DVT or PE, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel recommends maintaining indefinite anticoagulation over discontinuing it after a period of 3 to 6 months (strong recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: This recommendation assumes an average risk of bleeding and may not apply to patients with a high risk of bleeding. Clinicians should be aware that bleeding risk may change over time, so the balance between the desirable and undesirable consequences of indefinite anticoagulation should be reassessed periodically.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. We estimated that VTE recurrence after a recurrent unprovoked event was 12 events per 100 patient-years.6 Of these, 6.6 events per 100 patient-years correspond to DVT, and 5.4 events per 100 patient-years correspond to PE (Table 3).44 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/St8RZOwBDz4.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel reviewed the baseline risk of VTE recurrence used to estimate the absolute effect of indefinite treatment and considered it appropriate for the Latin American setting. Access to indefinite anticoagulation is probably limited within the region. However, the risk of significant morbidity and even mortality in individuals with recurrent unprovoked VTE events is very high. Therefore, health care systems should make efforts to be able to provide indefinite anticoagulation for this group of patients.

Conclusion

Because this is a strong recommendation, clinicians should focus on identifying and overcoming barriers to implementing indefinite anticoagulation. The most notorious barrier within the region is accessibility to proper anticoagulation.45 The use of DOACs for long-term anticoagulation may facilitate treatment of individuals with recurrent VTE events.

In patients with a provoked DVT or PE related to a chronic risk factor (eg, chronic immobility), should we use indefinite anticoagulation or discontinue anticoagulation after a period of 3 to 6 months?

Recommendation 10

In patients with a provoked DVT or PE related to a chronic risk factor (eg, chronic immobility), the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel recommends maintaining indefinite anticoagulation over discontinuing it after a period of 3 to 6 months (strong recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: This recommendation is applicable only to risk factors that persist over time and confer a relatively high risk of VTE recurrence (with the exception of cancer, which will be covered in an upcoming guideline).

This recommendation assumes an average risk of bleeding, and it may not apply to patients with a high risk of bleeding. Clinicians should be aware that bleeding risk may change over time, so potential benefits and harms of indefinite anticoagulation should be reassessed periodically.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. We estimated that the rate of incidence of VTE in patients with chronic risk factors was 9.7 events per 100 patient-years.7 Of these events, 5.3 per 100 patient-years correspond to DVT, and 4.4 per 100 patient-years correspond to PE (Table 3).44 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/BpHVm-91I7k.

Justification

This recommendation changed its strength. The original guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of indefinite anticoagulation, but the Latin American guideline panel made a strong recommendation with the same direction. The original guideline panel considered a more heterogenous population with different chronic risk factors for thrombosis when making the recommendation. For this recommendation, the Latin American panel focused on noninflammatory conditions that provide a high risk of VTE such as chronic immobility. For this specific population, the panel considered that the benefit of indefinite anticoagulation clearly outweighs its risk. Although guideline panelists considered that access to proper anticoagulation was limited within the region, given the high risk of significant morbidity and mortality, efforts should be made to provide indefinite anticoagulation to individuals with a VTE related to a chronic risk factor.

Conclusion

To effectively implement this recommendation, clinicians should carefully examine the nature of the chronic risk factor. This recommendation specifically addresses individuals with noninflammatory conditions (excluding, for example, antiphospholipid syndrome) and without cancer (which will be covered in an upcoming guideline). If the risk factor does not provide a high risk of VTE, or if it will disappear in time, clinicians and patients may consider using a definite period of anticoagulation.

In patients with recurrent provoked DVT or PE, should we use indefinite anticoagulation or discontinue anticoagulation after a period of 3 to 6 months?

Recommendation 11

In patients with recurrent provoked DVT or PE and high risk of recurrence, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests maintaining indefinite anticoagulation over discontinuing it after a period of 3 to 6 months (conditional recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: This recommendation applies to individuals in whom the VTE events were provoked by a minor risk factor, and at least 1 of these events has a high risk of recurrence. This recommendation also assumes that in cases of VTE associated with hospitalization or surgery, appropriate thromboprophylaxis was carried out, so it may not apply to patients who did not receive thromboprophylaxis. The recommendation also assumes an average risk of bleeding and may not apply to patients with a high risk of bleeding. The final decision will likely vary, depending on the severity of both thrombotic events (ie, DVT vs PE) and the nature of the risk factor (ie, a minor risk factor, such as hormone use vs a major risk factor such as surgery).

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. We estimated that the rate of VTE recurrence after a recurrent provoked event was 5.6 events per 100 patient-years.46 Of these events, 3.1 per 100 patient-years correspond to DVT, and 2.5 per 100 patient-years correspond to PE (Table 3).44 The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/qb-u-aqc4dU.

Justification

The original guideline panel made 2 separate conditional recommendations according to the risk of recurrence: one against indefinite anticoagulation in individuals with 2 provoked events of low risk, such as after surgeries, and another in favor of indefinite anticoagulation in individuals with recurrent provoked VTE, of which at least 1 had a high risk of recurrence, such as an unprovoked event. The Latin American guideline panel considered the second situation as more relevant to the region, since their perception was that many patients at high risk of recurrence were treated for only a limited time. Hence, they focused only on the second population.

Conclusion

The decision on whether to maintain indefinite anticoagulation in individuals with provoked VTE events likely will depend on the nature of risk factors involved. This recommendation specifically addresses individuals in which at least 1 of the VTE events had a high risk of recurrence, such as unprovoked events or events provoked by a chronic risk factor. Therefore, it may not apply in the case of recurrent VTE in which all the events are clearly related to transient risk factors.

In patients in whom an indefinite duration of antithrombotic therapy is preferred after completion of an initial defined duration course of therapy (3 to 6 months), should we maintain anticoagulants or use aspirin?

Recommendation 12

In patients in whom an indefinite duration of antithrombotic therapy is preferred after completion of an initial defined duration course of therapy (3 to 6 months), the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests anticoagulation over aspirin (conditional recommendation based on moderate certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁⨁◯).

Remarks: This recommendation places more value on the higher effectiveness of anticoagulation than on the lower cost of aspirin.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Table 3 summarizes the recommendations about secondary prevention. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/jYgUd8Ggd6w.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel considered that the majority of patients in need of indefinite treatment might be better off with anticoagulation than with aspirin. Specifically, with DOACs, the burden of anticoagulation is probably not greater than the burden of using aspirin, although DOACs may be significantly more expensive. However, even though aspirin is cheaper in the short term, its lower effectiveness compared with anticoagulation may lead to a higher total cost for the health care system in the middle or long term.

Conclusion

Indefinite use of antithrombotic medications is warranted in individuals at high risk of VTE recurrence, such as patients with unprovoked events (Recommendation 9) and those with a chronic risk factor (Recommendation 11) or recurrent events (Recommendations 10 and 12). In these circumstances, aspirin offers lower protection against new events than anticoagulation. In the past, the main reason to consider aspirin was the burden associated with anticoagulation with VKAs, for which strict follow-up was required. However, as DOACs become more available and affordable within the region, barriers to initiating anticoagulation will likely decrease.

In patients for whom an indefinite duration of DOAC treatment is preferred after completion of an initial defined duration course of therapy (3 to 6 months), should we use a standard dose or a lower dose of DOACs?

Recommendation 13

In patients in whom an indefinite duration of DOAC use is preferred after completion of an initial defined duration course of therapy (3 to 6 months), the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests using the standard dose of DOACs over a lower dose of DOACs (conditional recommendation based on low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁⨁◯◯).

Remarks: The evidence of effectiveness comes from studies from which patients who required extended anticoagulant therapy were excluded. Because this recommendation follows the recommendations about indefinite treatment in individuals with unprovoked events, events provoked by a chronic risk factor, or recurrent events, the panel considered that the majority of these patients should not be treated with lower doses. However, lower doses may be appropriate for individuals with a lower risk of thrombosis recurrence or a high risk of bleeding.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Table 3 summarizes the recommendations about secondary prevention. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/ysLL2zF-U70.

Justification

This recommendation changed its direction. The original guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of either standard or lower doses of DOACs. The Latin American guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of standard doses. After an initial course of anticoagulation, the effects of standard doses and lower doses of DOACs may be similar. However, there is considerable uncertainty, given the limitations of the available evidence (low-certainty evidence). In the context of uncertainty, the Latin American panel decided to suggest the use of standard doses for the following reasons. First, this recommendation follows conditional recommendations in favor of indefinite treatment in groups that have a high risk of VTE recurrence. Hence, standard doses may offer them a greater VTE risk reduction. Second, because there is limited availability of DOACs within the region, some nonstandard formulations may not be universally available.

Conclusion

Patients discussed in this guideline are generally at high risk of VTE recurrence (ie, unprovoked events related to a chronic risk factor or recurrent events). Therefore, they might benefit from standard doses of DOACs. However, lower doses may be appropriate if the risk of VTE is not considered high or if there are reasonable concerns regarding the risk of bleeding.

In patients with DVT or PE during treatment with VKAs, should we use low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or DOACs?

Recommendation 14

In patients with DVT or PE during treatment with VKAs, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests using LMWH over DOACs (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks: This recommendation places more value on the extensive experience of using LMWH for prothrombotic conditions. In addition, this recommendation assumes that failure of VKA treatment was not because of suboptimal anticoagulation. In such cases, ensuring optimal VKA dosing may be the best alternative. The panel emphasizes that clinicians should explore the underlying cause of thrombosis in patients with VTE during treatment with VKAs. The final choice of treatment should consider the underlying cause, patient’s values and preferences, and the cost and feasibility of each alternative.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/0_dHdSAWrJo.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. Both DOACs and LMWH are expensive, and their costs impose a significant access barrier to many patients in the region. The panel chose LMWH over DOACs after considering the extensive clinical experience with LMWH. DOACs are a newer class of drug, and it is reasonable to suppose that some health care systems have LMWH available but not DOACs.

Conclusion

A new VTE event that occurs while a patient is being treated with VKAs should alert clinicians and patients. A frequent reason is insufficient anticoagulation. Even in the highly controlled settings of randomized trials, patients are within the appropriate INR range Only 60% to 70% of the time, and the most typical failure is on the side of subanticoagulation.47–49 Clinicians should also consider alternative diagnoses that may increase the risk of VTE, such as cancer. Thus, a complete reevaluation of the clinical situation may be warranted.

Additional management issues

In patients who use aspirin for primary cardiovascular prevention and initiate anticoagulation for a DVT or PE, should we maintain aspirin or discontinue it?

Recommendation 15

In patients who use aspirin for primary cardiovascular prevention and initiate anticoagulation for a DVT or PE, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests against maintaining aspirin (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/CefPQE4u-cQ.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The Latin American guideline panel focused this recommendation on individuals who take aspirin to prevent primary cardiovascular events. This was part of the spirit of the original recommendation, but here it was made explicit in the recommendation statement.

Conclusion

A careful evaluation of the indication for aspirin is crucial to effectively implement this recommendation. The panel considered that the majority of patients without previous cardiovascular events who are using aspirin will be better off with anticoagulation alone. However, patients with a higher cardiovascular risk may benefit from the association of an antiplatelet agent and anticoagulant therapy. The same is probably true for patients who are being treated with aspirin because of a recent ischemic event.50

In patients receiving treatment for VTE who survive an episode of anticoagulation therapy–related major bleeding, should we resume oral anticoagulation therapy or discontinue it?

Recommendation 16

In patients receiving treatment for VTE who survive an episode of anticoagulation therapy–related major bleeding, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests resumption of oral anticoagulation therapy over discontinuation (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks: The decision on whether to resume anticoagulation may vary with the risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding as well as with the severity of the bleeding event experienced by the patient.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/4Ixh1o3zQ6c.

Justification

This recommendation did not change its direction or its strength. The panel considered that although these patients are at increased risk of new bleeding episodes, resuming anticoagulation will result in a net health benefit by reducing the risk of VTE events.

Conclusion

To decide whether to resume anticoagulation, clinicians need to consider the individual risk of bleeding and VTE events together along with the value that patients place on these outcomes. Patients who experience a drastic reduction in their quality of life because of thrombotic events will likely choose to resume anticoagulation. In contrast, if the bleeding event resulted in significant morbidity, patients may prefer not to resume anticoagulation. A shared decision-making approach exploring the values that patients place on preventing VTE or bleeding may be a way of implementing the recommendation.

The optimal timing of anticoagulation resumption remains uncertain and is likely variable with different patients. The panel felt that waiting at least 2 weeks but not more than 90 days after the bleeding event is reasonable. However, earlier resumption may be considered if the source of bleeding was identified and corrected.

In patients with VKA-related life-threatening bleeding during treatment for VTE, should we use 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) or fresh frozen plasma (FFP)?

Recommendation 17

In patients with VKA-related life-threatening bleeding during treatment of VTE, the ASH Latin American Guideline Panel suggests using either 4-factor PCCs or FFP according to local availability and clinical circumstances (conditional recommendation based on very low certainty in the evidence about effects ⨁◯◯◯).

Remarks: The panel emphasizes that clinicians should favor the fastest option according to local availability. Patients with heart disease in whom volume overload is considered a significant risk might benefit from 4-factor PCCs. When patients place a high value on avoiding infection transmission, or in contexts in which the risk of transfusion-related infections is high, 4-factor PCCs may be a better option. However, in many settings in the region, availability of 4-factor PCCs is limited. In such scenarios, FFP is an alternative for reversing the effects of VKAs.

Summary of the evidence

No additional evidence on the efficacy or safety of the intervention was identified. Mainly because of their cost, PCCs are not available in a substantial number of centers within the region. The EtD framework for these recommendations is available online at https://guidelines.ash.gradepro.org/profile/9e6hDjjbptM.

Justification

This recommendation changed its direction. The original guideline panel made a conditional recommendation in favor of PCC, but the Latin American panel suggested both PCCs and FFP as alternatives. The identified evidence did not show substantial differences in outcomes important to patients with PCCs or FFP. Although PCCs are easier and faster to administer, their price is higher than that of FFP, and they are not typically available in many settings in the region.

Conclusion

In an emergency situation like this, clinicians should always favor the fastest option according to local availability. In cases in which both interventions are equally available and accessible, other factors such as clinical considerations (eg, risk of volume overload or transfusion-related infections) or resource considerations (eg, insurance coverage) may guide the decision.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ASH guideline panels that developed the source guidelines as well as ASH and the McMaster GRADE Centre for sharing the data that made these guidelines possible.

Authorship

Contribution: I.N. and H.S. developed the methods for this adaptation; I.N. and A.I. led panel meetings; I.N. and A.I. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript on the basis of authors’ suggestions; guideline panel members I.N., A.I., R.A., G.L.B., P.C., C.C.C., M.C.G.E., P.P.G.L., J.P., L.A.M.-G., S.M.R., J.C.S., and M.L.T.V. critically reviewed the manuscript and provided suggestions for improvement; knowledge synthesis team members I.N., A.I., F.V., L.K., G.R., and H.S. contributed to the guidelines with evidence summaries; and all authors approved the content of the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: See supplements 2 and 3.

Correspondence: Ignacio Neumann, Department of Internal Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Avda. Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins 340, Santiago, Chile: e-mail: ignacio.neumann@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.