Key Points

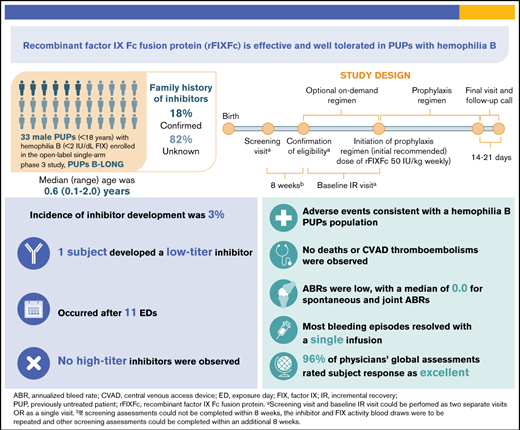

PUPs B-LONG is the first study of extended half-life rFIXFc in previously untreated hemophilia B patients.

rFIXFc was effective and well tolerated in PUPs with hemophilia B, with an incidence of inhibitors of 3%.

Abstract

PUPs B-LONG evaluated the safety and efficacy of recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc) in previously untreated patients (PUPs) with hemophilia B. In this open-label, phase 3 study, male PUPs (age <18 years) with hemophilia B (≤2 IU/dL of endogenous factor IX [FIX]) were to receive treatment with rFIXFc. Primary end point was occurrence of inhibitor development, with a secondary end point of annualized bleed rate (ABR). Of 33 patients who received ≥1 dose of rFIXFc, 26 (79%) were age <1 year at study entry and 6 (18%) had a family history of inhibitors. Twenty-eight patients (85%) received prophylaxis; median dosing interval was 7 days, with an average weekly dose of 58 IU/kg. Twenty-seven patients (82%) completed the study. Twenty-one (64%), 26 (79%), and 28 patients (85%) had ≥50, ≥20, and ≥10 exposure days (EDs) to rFIXFc, respectively. One patient (3.03%; 95% confidence interval, 0.08% to 15.76%) developed a low-titer inhibitor after 11 EDs; no high-titer inhibitors were detected. Twenty-three patients (70%) had 58 treatment-emergent serious adverse events; 2 were assessed as related (FIX inhibition and hypersensitivity in 1 patient, resulting in withdrawal). Median ABR was 1.24 (interquartile range, 0.00-2.49) for patients receiving prophylaxis. Most (>85%) bleeding episodes required only 1 infusion for bleed resolution. In this first study reporting results with rFIXFc in pediatric PUPs with hemophilia B, rFIXFc was well tolerated, with the adverse event profile as expected in a pediatric hemophilia population. rFIXFc was effective, both as prophylaxis and in the treatment of bleeding episodes. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02234310.

Introduction

Hemophilia B is an X-linked recessive disorder resulting from factor IX (FIX) deficiency, with a reported incidence of 5.0 cases per 100 000 male births for hemophilia B overall and 1.5 cases per 100 000 male births for severe hemophilia B.1 Severe hemophilia B is characterized by recurrent spontaneous bleeding episodes as well as prolonged bleeding after injury. Sites of bleeding can include joints, muscles, soft tissues, and internal organs. Bleeding episodes that occur in the joints (hemarthrosis) and muscles can cause pain and lead to disability and arthropathy, affecting quality of life2; bleeding at other sites (eg, intracranial hemorrhage) can be life threatening.3

The current standard of care for hemophilia B is prophylactic FIX replacement to prevent bleeding episodes. Clinical studies have demonstrated improved outcomes with the use of early prophylaxis, highlighting its value.2 To sustain FIX levels aimed at preventing spontaneous bleeding episodes and maintaining joint health, prophylactic regimens using standard half-life (SHL) recombinant FIX (rFIX) and plasma-derived FIX products typically require multiple (≥2) infusions per week. The relatively high frequency of SHL FIX infusions may reduce treatment adherence as a result of the burden on patients, particularly pediatric patients, and their caregivers.4

Extended half-life (EHL) rFIX products offer the potential for less frequent dosing compared with SHL rFIX and increased protection against breakthrough bleeding episodes or increased physical activity by maintaining higher FIX levels.2,5 The half-lives of EHL products have been shown to be significantly longer in children and adults, with studies reporting up to fivefold longer half-lives than SHL rFIX treatments.6–8 Less frequent dosing with EHL products has the potential to improve adherence for patients who are deterred by the frequency of dosing with SHL products, contributing to improved clinical outcomes.9

The most significant complication of hemophilia treatment with factor replacement is inhibitor development, with patients most at risk during the first 50 exposure days (EDs) of factor replacement.10 Historically, inhibitors have been reported in 1% to 5% of patients with hemophilia B and are primarily observed in individuals with severe hemophilia B.11 However, cumulative inhibitor incidences of 8.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.8% to 13.0%) at 50 EDs and 9.3% (95% CI, 4.4% to 14.1%) at 75 EDs were recently reported by the PedNet Group in an unselected, well-defined cohort of previously untreated patients (PUPs) with severe hemophilia B.12

Recombinant factor IX Fc fusion protein (rFIXFc [Alprolix; Sanofi, Waltham, MA and Sobi, Stockholm, Sweden]) was the first EHL FIX therapy approved for adults and children with hemophilia B as routine prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes, treat and control bleeding episodes, and manage bleeding in the perioperative setting.13 It consists of a single molecule of rFIX covalently fused to the dimeric Fc domain of immunoglobulin G1, taking advantage of the natural immunoglobulin G recycling pathway to extend FIX half-life.14,15 The safety and efficacy of rFIXFc have been demonstrated in previously treated patients (≥100 EDs to FIX products) with hemophilia B age ≥12 years (B-LONG study; registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01027364)7 and in previously treated patients (≥50 EDs to FIX products) age <12 years (Kids B-LONG study; registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01440946).16 The B-YOND extension study, with cumulative duration up to 6.5 years, confirmed the long-term safety and efficacy of rFIXFc with extended dosing intervals in previously treated patients.17 Here we report the results of the PUPs B-LONG study (NCT02234310), the first trial investigating the safety and efficacy of rFIXFc in pediatric PUPs with hemophilia B (≤2 IU/dL of endogenous FIX).

Patients and methods

Study design

PUPs B-LONG was an open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 3 study conducted at 24 sites in 11 countries in which male PUPs age <18 years with hemophilia B (≤2 IU/dL [≤2%] of endogenous FIX activity) received rFIXFc. Investigators obtained independent ethics committee approval of the study protocol, all amendments, informed consent form, and other required study documents. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all local regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants’ parents/legal guardians.

Investigators could treat patients with rFIXFc on demand at investigators’ discretion before initiating prophylaxis, in accordance with the local standard of care. It was expected that the prophylactic regimen would be initiated before or immediately after a third episode of hemarthrosis, to align with global standards of care. Prophylactic treatment consisted of an initial recommended dose of 50 IU/kg weekly, with adjustments to dose and dosing interval based on assessment of pharmacokinetic data, physical activity, and bleeding episodes. The treatment period was ≥50 EDs to rFIXFc, unless end of study (EOS) or study withdrawal was declared. EOS occurred after ≥20 patients reached ≥50 EDs to rFIXFc. One ED was defined as a 24-hour period in which a patient received ≥1 rFIXFc dose, with the time of the first infusion (injection) marking the start of the ED.

Immune tolerance induction up to 24 months from inhibitor development or to the EOS (whichever came first) was allowed for patients who developed a high-titer inhibitor or a low-titer inhibitor where bleeding episodes were poorly controlled after exposure to rFIXFc. Those who developed a low-titer inhibitor without bleeding complications were to continue in the study with the same or increased rFIXFc dosing at the discretion of the investigator.

Patient eligibility

Male PUPs age <18 years at the time of informed consent with hemophilia B (≤2 IU/dL [≤2%] of endogenous FIX activity) were enrolled in the study. A PUP was defined as a patient who had no prior exposure to FIX concentrates, except for up to 3 infusions of commercially available rFIXFc before the confirmation of eligibility and <28 days before screening. Main exclusion criteria included exposure to blood components or infusion with an FIX concentrate (including plasma derived) other than rFIXFc, history of positive inhibitor test, history of hypersensitivity reactions associated with any rFIXFc administration, other coagulation disorder in addition to hemophilia B, and any concurrent clinically significant major disease.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the occurrence of inhibitor development, with a positive inhibitor defined as an inhibitor test result of ≥0.60 BU/mL that was confirmed by a second test result of ≥0.60 BU/mL from a separate sample drawn 2 to 4 weeks after the original sample. Both tests must have been performed by the central laboratory using the Nijmegen-modified Bethesda assay. A low-titer inhibitor was defined as a positive inhibitor with a result of ≥0.60 to <5.0 BU/mL; a high-titer inhibitor was defined as a positive inhibitor with a result of ≥5.0 BU/mL. Patients were tested at each study visit and at each ED milestone visit (5 [±2], 10 [10-15], 20 [20-25], and 50 [50-55] EDs).

Secondary end points included annualized bleed rate (ABR; overall, spontaneous, traumatic, and spontaneous joint); total number of EDs; total annualized rFIXFc consumption; number of infusions and rFIXFc dose per infusion required to resolve a bleeding episode; assessment of response to treatment with rFIXFc for bleeding episodes using a 4-point bleed response scale (excellent, good, moderate, or none) by investigator for individual bleeding episodes treated in the clinic and by caregiver for all other bleeding episodes; physician’s global assessment of the patient’s response to the assigned rFIXFc regimen, including either how bleeding episodes responded to infusions (considering both dose and frequency) or the rate of breakthrough bleeding during prophylaxis, using a 4-point scale (excellent, effective, partially effective, or ineffective) every 12 weeks; and incremental recovery (IR) measured by the 1-stage activated partial thromboplastin time clotting assay.

Statistical analyses

Safety analyses were based on the safety analysis set, defined as all patients who received at least 1 dose of study rFIXFc. Efficacy analyses were based on the full analysis set, defined as all enrolled patients who received at least 1 dose of study rFIXFc.

The primary analysis of safety was based on the incidence of inhibitors assessed by the Nijmegen-modified Bethesda assay. The incidence of inhibitors was determined as any patient who developed an inhibitor after the initial rFIXFc administration in the safety analysis set. An exact 95% CI for the proportion of patients with a positive inhibitor was calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for binomial proportion. Incidence of inhibitor formation was also summarized by ED milestones of ≥10, ≥20, and ≥50 EDs to support the primary analysis; incidence was calculated based on the number of patients who tested positive for an inhibitor in that category, regardless of how many days they were exposed to rFIXFc, divided by the number of patients who reached an ED milestone of at least 10, 20, and 50 EDs or who had an inhibitor.

Secondary analyses of efficacy were based on descriptive statistics. Assessment of efficacy was performed during the efficacy period where a patient must have had at least 1 day of treatment for an on-demand regimen or at least 2 prophylactic infusions for a prophylactic regimen. ABR calculations were performed by dividing the number of bleeding episodes during the efficacy period by the total number of days during the efficacy period and multiplying by 365.25. ABR among patients with ≥50 EDs was investigated as an exploratory sensitivity analysis. Annualized consumption for each patient was calculated by analyzing the total international units per kilogram (IU/kg) of rFIXFc during the efficacy period divided by the total number of days during the efficacy period and multiplied by 365.25.

Results

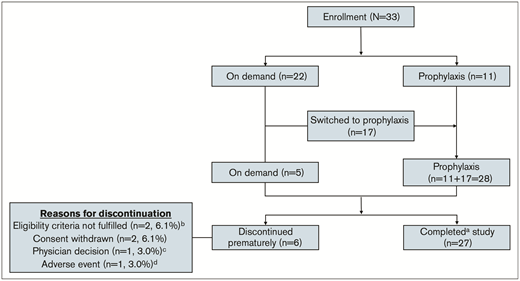

Of 33 patients enrolled and treated in the study, 22 (67%) started with on-demand treatment and 11 (33%) started with a prophylactic regimen. Seventeen (77%) of 22 patients who initially received an on-demand treatment regimen subsequently switched to prophylaxis, for a total of 28 patients receiving prophylaxis during the study. Twenty-seven patients (82%) completed the study, and 6 (18%) discontinued the study early (Figure 1).

Patient disposition.aDid not discontinue from the study prematurely. Patients who discontinued participation in the study because the study was stopped were considered to have completed the study. bPatients were discontinued because of central laboratory results indicating baseline FIX activity level >2%. cPatient was discontinued because of site closing. dPatient was withdrawn from the study because of treatment-emergent serious adverse event (TESAE) of hypersensitivity and FIX inhibition, which were considered related to study treatment.

Patient disposition.aDid not discontinue from the study prematurely. Patients who discontinued participation in the study because the study was stopped were considered to have completed the study. bPatients were discontinued because of central laboratory results indicating baseline FIX activity level >2%. cPatient was discontinued because of site closing. dPatient was withdrawn from the study because of treatment-emergent serious adverse event (TESAE) of hypersensitivity and FIX inhibition, which were considered related to study treatment.

Patient baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most patients were age <1 year (n = 26; 79%), with a median age of 7.2 (range, 0.96-24.0) months at the time of enrollment. Most patients were White (67%); 1 each was Black or Asian (3%), and 2 patients were Hispanic or Latino (6%). A majority (n = 29 of 33) of patients had FIX activity at screening <1 IU/dL. The remaining patients (n = 4 of 33) had FIX activity at screening ≥1 to ≤2 IU/dL of FIX.

Overall baseline demographics and characteristics

| . | Overall (N = 33) . |

|---|---|

| Age, mo* | |

| Median | 7.2 |

| Range | 0.96–24.0 |

| Age category, y, n (%) | |

| <1 | 26 (78.8) |

| 1 | 5 (15.2) |

| 2 | 2 (6.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 22 (66.7) |

| Black | 1 (3.0) |

| Asian | 1 (3.0) |

| Not reported because of confidentiality regulations | 5 (15.2) |

| Other | 4 (12.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (6.1) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 26 (78.8) |

| Not reported because of confidentiality regulations | 5 (15.2) |

| Geographic location, n (%)† | |

| Europe | 20 (60.6) |

| North America | 11 (33.3) |

| Other | 2 (6.1) |

| Family history of inhibitors, n (%) | |

| Yes | 6 (18.2) |

| No | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 27 (81.8) |

| F9 genotype, n (%) | |

| Missense | 14 (42.4) |

| Nonsense | 11 (33.3) |

| Promoter or regulatory region mutation | 2 (6.1) |

| Large structure change (>50 base pairs) | 1 (3.0) |

| Frameshift | 1 (3.0) |

| Splice site change | 1 (3.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (9.1) |

| Vaccination within the last year, n (%) | |

| Yes | 27 (81.8) |

| No | 6 (18.2) |

| . | Overall (N = 33) . |

|---|---|

| Age, mo* | |

| Median | 7.2 |

| Range | 0.96–24.0 |

| Age category, y, n (%) | |

| <1 | 26 (78.8) |

| 1 | 5 (15.2) |

| 2 | 2 (6.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 22 (66.7) |

| Black | 1 (3.0) |

| Asian | 1 (3.0) |

| Not reported because of confidentiality regulations | 5 (15.2) |

| Other | 4 (12.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (6.1) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 26 (78.8) |

| Not reported because of confidentiality regulations | 5 (15.2) |

| Geographic location, n (%)† | |

| Europe | 20 (60.6) |

| North America | 11 (33.3) |

| Other | 2 (6.1) |

| Family history of inhibitors, n (%) | |

| Yes | 6 (18.2) |

| No | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 27 (81.8) |

| F9 genotype, n (%) | |

| Missense | 14 (42.4) |

| Nonsense | 11 (33.3) |

| Promoter or regulatory region mutation | 2 (6.1) |

| Large structure change (>50 base pairs) | 1 (3.0) |

| Frameshift | 1 (3.0) |

| Splice site change | 1 (3.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (9.1) |

| Vaccination within the last year, n (%) | |

| Yes | 27 (81.8) |

| No | 6 (18.2) |

Percentages are based on number of patients with data available in safety analysis set.

Age at time of informed consent.

Europe includes Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. North America includes Canada and the United States. Other countries include Australia and New Zealand.

Five patients (15%) experienced spontaneous bleeding episodes in the 3 months before screening, with 1 of these experiencing a spontaneous joint bleed. Two patients (6%) had been circumcised before study entry. Six (18%) had a family history of inhibitors, although most patients (n = 27; 82%) reported that a family history of inhibitors was unknown. The most common F9 mutation was missense mutation (n = 14; 42%), followed by nonsense mutation (n = 11; 33%); distribution of these genotypes was representative of a hemophilia B population.18

Central venous access device insertion

Overall, 16 patients (48.5%) had a central venous access device (CVAD) inserted during the study. The median age at CVAD insertion was 12.6 (range, 6.6-26.8) months. Nine patients (56%) were receiving prophylaxis at the time of CVAD insertion, whereas 7 (44%) were receiving on-demand treatment at the time of insertion.

rFIXFc exposure

The median treatment duration was 22.9 (range, 0.3-164.2) weeks for the on-demand regimen and 77.5 (range, 10.1-134.0) weeks for the prophylactic regimen, with an overall median treatment duration of 83.0 (range, 6.7-226.7) weeks. The median number of EDs was 76 (range, 1-137) overall, with 88% (n = 29) reaching ≥5, 85% (n = 28) reaching ≥10, 79% (n = 26) reaching ≥20, and 64% (n = 21) reaching ≥50 EDs. Eighteen (55%) and 11 patients (33%) reached ≥75 and ≥100 EDs, respectively.

For the on-demand regimen, the median number of EDs was 2.5 (range, 0-26), with 32% (n = 7) reaching ≥5, 9.1% (n = 2) reaching ≥10, and 4.5% (n = 1) reaching ≥20 EDs.

For the prophylactic regimen, the median number of EDs was 81.5 (range, 10-136); 100% (n = 28) reached ≥5 and ≥10, 93% (n = 26) reached ≥20, and 71% (n = 20) reached ≥50 EDs. The median age at the start of prophylaxis was 12.7 (range, 6.9-30.6) months.

For those with a treated bleed, the median age at first treated bleed was 16.2 (range, 5.4-50.5) months.

Incremental recovery

At baseline, the median IR value for patients receiving the on-demand regimen was 0.7 (interquartile range [IQR]), 0.6-0.8) IU/dL per IU/kg, and the IR observed for those in the prophylactic treatment group was 0.7 (IQR, 0.7-0.8) IU/dL per IU/kg. IR remained stable throughout the study.

Occurrence of inhibitor development

The incidence of inhibitor formation was 3.57% (95% CI, 0.09% to 18.35%) in patients reaching ≥10 EDs to rFIXFc or with an inhibitor (n = 28), 3.70% (95% CI, 0.09% to 18.97%) in those reaching ≥20 EDs to rFIXFc or with an inhibitor (n = 27), and 4.55% (95% CI, 0.12% to 22.84%) in those reaching ≥50 EDs to rFIXFc or with an inhibitor (n = 22). Of the 33 patients exposed to rFIXFc, 1 (3.03%; 95% CI, 0.08% to 15.76%) developed a low-titer inhibitor after 11 EDs. This patient with severe hemophilia B (<1 IU/dL of FIX), who started the study receiving a prophylactic regimen, also experienced a treatment-emergent serious adverse event (TESAE) of hypersensitivity during the 11th infusion of rFIXFc (after 10 EDs). The patient had presented on the same day with new subcutaneous hematomas and bruises, and because he was becoming more active, his weekly dose of rFIXFc was increased from 58 to 70 IU/kg (11th infusion). The TESAE of hypersensitivity (flushing of the face and arms, agitation, cough, sweating, tachycardia, and urticaria of legs and face) was assessed as related to rFIXFc by the investigator, resolved with treatment (budesonide, cetirizine, salbutamol, and chlorphenamine maleate) on the same day, and led to study drug discontinuation (the 11th infusion was the last dose received) and subsequent withdrawal from the study. The patient had a FIX genotype classified as high risk for inhibitor development (nonsense mutation) and experienced a treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) of pharyngitis in the preceding month that was considered mild and not related to treatment. The patient was White and did not undergo minor or major surgery during the study. Family history of inhibitor development was reported as unknown. The peak inhibitor titer was 1.3 BU/mL. The patient received bypassing therapy with recombinant factor VIIa on 3 separate occasions (because of hemarthrosis, surgery, and facial trauma) after rFIXFc discontinuation.

No high-titer inhibitors were detected in this study.

AEs

There were totals of 57.5 patient-years of follow-up and 2233 EDs. Of the 33 patients who received ≥1 dose of rFIXFc, 30 (91%) experienced ≥1 TEAE (Table 2). Overall, the most common type of TEAE was infection (26 [79%] of 33). The most common TEAEs of infection were nasopharyngitis (11 [33%] of 33); upper respiratory tract infection (7 [21%] of 33); and ear infection, otitis media, pharyngitis, varicella, and viral infection (4 each [12%] of 33).

Overall summary of rFIXFc TEAEs

| . | Overall (N = 33) . |

|---|---|

| Total no. of TEAEs* | 387 |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE, n (%) | 30 (90.9) |

| Patients with ≥1 related TEAE%, n (%)† | 2 (6.1) |

| Patients who discontinued treatment and/or study because of AE, n (%) | 1 (3.0) |

| Total no. of TESAEs‡ | 58 |

| Patients with ≥1 TESAE, n (%) | 23 (69.7) |

| Patients with ≥1 related TESAE, n (%)† | 1 (3.0)§ |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| . | Overall (N = 33) . |

|---|---|

| Total no. of TEAEs* | 387 |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE, n (%) | 30 (90.9) |

| Patients with ≥1 related TEAE%, n (%)† | 2 (6.1) |

| Patients who discontinued treatment and/or study because of AE, n (%) | 1 (3.0) |

| Total no. of TESAEs‡ | 58 |

| Patients with ≥1 TESAE, n (%) | 23 (69.7) |

| Patients with ≥1 related TESAE, n (%)† | 1 (3.0)§ |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 (0.0) |

Percentages are based on overall number of patients.

Includes TESAEs.

AEs with undefined relationship were included with related AEs.

TESAEs reported in 1 patient each were: anemia, FIX inhibition, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, phimosis, inguinal hernia, tongue hemorrhage, vessel puncture-site hematoma, hypersensitivity, croup infectious, gastroenteritis, infusion-site pustule, lower respiratory tract infection, respiratory tract infection, staphylococcal bacteremia, viral infection, viral rash, accidental exposure to product, closed head injury (craniocerebral injury), face injury, skull fracture, subdural hematoma, compartment syndrome, hemarthrosis, coma, febrile convulsion, spinal cord hematoma, tongue biting, redundant prepuce, and hematoma.

This patient had hypersensitivity reaction and tested positive for inhibitor development and discontinued study because of AEs.

Of the 33 patients who received at least 1 dose of rFIXFc, 23 (70%) experienced ≥1 TESAE. Overall, the most common TESAEs (reported by ≥2 patients) were central venous catheterization (9 [27%] of 33), fall (5 [15%] of 33), poor venous access (3 [9%] of 33), and head injury (3 [9%] of 33). The remaining TESAEs were reported in 1 patient (3%) each (Table 2). There were 2 life-threatening events, 1 being spontaneous subdural hematoma in 1 patient and the other being spontaneous spinal cord hematoma in a second patient. Both occurred while patients were receiving an on-demand regimen.

Of the 30 patients who experienced ≥1 TEAE, 2 (6.1%) experienced 5 TEAEs that were assessed as related to treatment with rFIXFc. Those events included 3 TEAEs of injection-site erythema in 1 patient, all assessed as nonserious, and TESAEs of inhibitor development (low-titer inhibitor; peak titer, 1.3 BU/mL) and hypersensitivity, resulting in study drug discontinuation and subsequent withdrawal from the study (also described under “Occurrence of inhibitor development”) in another patient. There were no deaths. No TEAEs of CVAD thrombosis or anaphylaxis were reported.

ABR

Table 3 shows the median overall ABR during the efficacy period for on-demand and prophylactic treatment regimens. The overall median ABR for patients receiving on-demand treatment was 0.21 (IQR, 0.00-5.00).

Response to rFIXFc treatment: ABR by bleed type and treatment regimen

| . | Treatment regimen, median (IQR) . | |

|---|---|---|

| On demand (n = 22) . | Prophylactic (n = 28) . | |

| Overall | 0.21 (0.00-5.00) | 1.24 (0.00-2.49) |

| Spontaneous | 0.00 (0.00-2.26) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| Traumatic | 0.00 (0.00-1.62) | 0.91 (0.00-1.80) |

| Traumatic joint | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| Spontaneous joint | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| . | Treatment regimen, median (IQR) . | |

|---|---|---|

| On demand (n = 22) . | Prophylactic (n = 28) . | |

| Overall | 0.21 (0.00-5.00) | 1.24 (0.00-2.49) |

| Spontaneous | 0.00 (0.00-2.26) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| Traumatic | 0.00 (0.00-1.62) | 0.91 (0.00-1.80) |

| Traumatic joint | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

| Spontaneous joint | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.00) |

ABR is total number of bleeding episodes during efficacy period extrapolated to 1-y time interval.

For patients receiving prophylaxis, the overall median ABR was 1.24 (IQR, 0.00-2.49). In the 20 patients who had ≥50 EDs with a prophylactic regimen, the overall median ABR was 1.32 (IQR, 0.39-3.03). The median ABR for spontaneous bleeding episodes was 0.00 (IQR, 0.00-0.00) with the prophylactic regimen; 23 (82%) of 28 patients had 0 spontaneous bleeding episodes. The median ABR for traumatic bleeding episodes was 0.91 (IQR, 0.00-1.80) in the prophylactic group and 0.00 (IQR, 0.00-0.00) for both spontaneous and traumatic joint bleeding episodes.

rFIXFc consumption and dosing interval

The overall median annualized rFIXFc consumption was 2673.3 (IQR, 1723.6-3123.2) IU/kg. The median annualized rFIXFc consumption was 203.2 (IQR, 0.0-840.5) IU/kg for patients receiving the on-demand treatment regimen and 3175.0 (IQR, 2919.0-3629.8) IU/kg for those receiving prophylaxis. The median average weekly dose for patients receiving the prophylactic regimen was 58.0 (IQR, 52.5–65.1) IU/kg, and the median average dosing interval was 7 (IQR, 7.0-7.1) days. Twenty-two (79%) of 28 patients receiving prophylaxis maintained their dosing schedule, whereas 4 (14%) experienced 1 dosing interval change, and 1 patient each (4%) experienced 2 or 3 changes. Changes in dosing interval were most frequently for extension of the dosing interval; 1 patient moved from 5 to 7 days, 2 patients moved from 7 to 14 days, and another moved from every 3 days to twice weekly, whereas 1 patient moved from a 7-day to a 5-day dosing regimen and another moved to on-demand treatment.

Treatment compliance

For those who received prophylaxis, a dose compliance rate (proportion of doses received within 80% to 125% of the prescribed dose) ≥80% was achieved by 23 (82%) of 28 patients. A dosing interval compliance rate, or proportion of doses taken within ±36 hours of the prescribed day or time, of ≥80% was achieved by 19 (68%) of 28 patients. A compliance rate to both dose and interval of ≥80% was achieved by 16 (57%) of 28 patients.

Response to rFIXFc treatment: number of infusions and dose required to resolve a bleeding episode

Twenty-three (85%) of 27 bleeding episodes in the on-demand group and 51 (88%) of 58 bleeding episodes in the prophylaxis group were resolved with a single rFIXFc infusion, whereas 24 (89%) in the on-demand group and 56 (97%) in the prophylaxis group required ≤2 infusions for resolution, respectively (Table 4). The median number of infusions required to resolve a bleeding episode was 1 (IQR, 1-1) for each regimen.

Number of infusions required to resolve bleeding episodes

| . | Treatment regimen . | |

|---|---|---|

| On demand (n = 22) . | Prophylactic (n = 28) . | |

| No. of bleeding episodes | 27 | 58 |

| Per bleeding episode, n (%)* | ||

| 1 | 23 (85.2) | 51 (87.9) |

| 2 | 1 (3.7) | 5 (8.6) |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| 4 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| >4 | 2 (7.4)† | 0 (0.0) |

| Infusions required to resolve bleeding episodes | ||

| Mean | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| SD | 7.4 | 0.5 |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| IQR | 1.0-1.0 | 1.0-1.0 |

| Range | 1-31 | 1-4 |

| . | Treatment regimen . | |

|---|---|---|

| On demand (n = 22) . | Prophylactic (n = 28) . | |

| No. of bleeding episodes | 27 | 58 |

| Per bleeding episode, n (%)* | ||

| 1 | 23 (85.2) | 51 (87.9) |

| 2 | 1 (3.7) | 5 (8.6) |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| 4 | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.7) |

| >4 | 2 (7.4)† | 0 (0.0) |

| Infusions required to resolve bleeding episodes | ||

| Mean | 3.2 | 1.2 |

| SD | 7.4 | 0.5 |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| IQR | 1.0-1.0 | 1.0-1.0 |

| Range | 1-31 | 1-4 |

Investigators could treat patients with rFIXFc on demand at investigators’ discretion before initiating prophylaxis, in accordance with local standard of care. Therefore, patients may appear in >1 treatment regimen group. All infusions administered from initial sign of bleeding episode until last date/time within bleed window are counted.

SD, standard deviation.

Percentages are based on total number of bleeding episodes in each group.

One episode of spontaneous subdural hematoma in 1 patient; 1 episode of spontaneous spinal cord hematoma in 1 patient.

The median total rFIXFc doses required to resolve bleeding episodes were 91.7 (IQR, 69.0-136.4) IU/kg and 78.7 (IQR, 53.6–104.9) IU/kg for patients in the on-demand and prophylactic treatment groups, respectively. The median average dose per infusion was 88.5 (IQR, 69.0-114.7) IU/kg for those receiving the on-demand regimen and 71.9 (IQR, 52.5-100.8) IU/kg for those receiving prophylaxis.

Of the infusions with an available assessment, the patient’s response to the infusion for a bleeding episode was assessed by the patient/caregiver as excellent or good for 22 (100%) of 22 on-demand infusions and 50 (88%) of 57 prophylactic infusions.

Assessment of response to rFIXFc regimen

For the overall study population, a majority (96%) of physicians’ global assessments of patient response to rFIXFc regimen were excellent.

Discussion

In this first report of the safety and efficacy of rFIXFc in PUPs, the study population was generally representative of the global population of PUPs with hemophilia B.12,19 Enrolled patients were very young, as would be expected of PUPs, with a majority age <1 year. The medical and surgical histories of the study population were also typical of the global population in the developed world. The dosing regimens used in this study were representative of the treatment for PUPs when they begin factor replacement therapy, with most patients starting with on-demand treatment and transitioning to prophylactic treatment. Patients maintained high rates of compliance with rFIXFc.

rFIXFc was generally well tolerated, with no unanticipated safety findings in PUPs with hemophilia B. The incidence of inhibitors at ≥50 EDs was 4.55% (95% CI, 0.12% to 22.84%), which was consistent with historical rates of inhibitor development in hemophilia B11,20 ,21 but was lower than the rate reported by the PedNet Group in PUPs with severe hemophilia B (8.4% at 50 EDs [95% CI, 3.8% to 13.0%] and 9.3% at 75 EDs [95% CI, 4.4% to 14.1%]) and an interim report on EHL N9-GP use (estimated incidence, 6.1% [1‐sided 97.5% upper CI, 22.4%]).12,19 However, comparison between studies should be made cautiously. In the PedNet study, half of the inhibitors were high titer, whereas no high-titer inhibitors were detected in the present study. Treatment in the PedNet study could include any type of FIX product, although 71% of participants were initially exposed to rFIX. Also, in PUPs B-LONG, only 21 of the 33 patients were followed to 50 EDs. Because the size of the hemophilia B population is limited, the sample size is based on clinical rather than statistical considerations. In the interim analysis of N9-GP in PUPs, 2 patients who developed high-titer inhibitors were minimally treated, having had exposure to different rFIX products other than N9-GP before participation in the study.

The type and incidence of TEAEs and TESAEs observed in the study were similar to those expected for a pediatric PUP population with hemophilia B. There were no reports of anaphylaxis, but there was 1 report of serious hypersensitivity assessed as related to rFIXFc, which occurred in the same patient who also developed a low-titer inhibitor after 11 EDs. This patient had risk factors for inhibitor development, including a high-risk FIX genotype (nonsense mutation) and a TEAE of infection before the development of inhibitors. Patients with hemophilia B often experience allergic manifestations to FIX concentrates at the time of inhibitor development.22,23

rFIXFc was effective as prophylaxis and for the treatment of bleeding episodes in PUPs with hemophilia B. Overall, patients in this study experienced low ABRs, including low spontaneous, traumatic, and spontaneous or traumatic joint ABRs, with a median dosing interval of 7 days and a majority not requiring dosing interval changes. A majority of bleeding episodes required only 1 infusion for bleed resolution. These findings are consistent with previously published data on the use of rFIXFc in previously treated patients, confirming the ability of rFIXFc to achieve low ABRs with extended dosing intervals in this very young patient population.7,16 ,24 ,25

The median age at study start for this cohort was 7.2 months; however, the median age at the start of prophylaxis was >1 year. The occurrence of life-threatening bleeds in 2 patients during an on-demand treatment period highlights the value of primary prophylaxis in children with hemophilia. Use of an EHL rFIX, such as rFIXFc, may provide a less burdensome treatment option for primary prophylaxis in very young children such as those in this cohort. Of note, 16 patients in this population (N = 33) had a CVAD, with a median age at implant of 12.6 months; 9 patients were receiving prophylaxis at the time of CVAD insertion, and 3 had the CVAD placed immediately before starting prophylaxis. Insertion of a CVAD in these young patients may reflect the practice of their respective hemophilia treatment centers.

The results of this study, the first completed study with an EHL rFIX in PUPs with hemophilia B, demonstrated that rFIXFc was generally well tolerated. The incidence of inhibitor development was consistent with other FIX products, with 1 low-titer inhibitor and no high-titer inhibitors detected. In addition, rFIXFc was effective, both as prophylaxis and in the treatment of bleeding episodes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Peter Loonan (Sanofi) and Vita Data Sciences for providing programming support. The authors also acknowledge Ashleigh Pulkoski-Gross and Jennifer Alexander (JK Associates, Inc., part of Fishawack Health) for providing medical writing; this support was funded by Sanofi and Sobi.

The PUPs B-LONG study was sponsored by Sanofi (Cambridge, MA) and Sobi (Stockholm, Sweden).

Authorship

Contribution: B.N., A.K., A.S., A.R., M. Recht, M. Ragni, J.C., K.F., and R.L. collected, analyzed, and interpreted data and provided critical revision of the manuscript; S.G., S.M., D.J., and B.W. analyzed and interpreted data and provided critical revision of the manuscript; and all authors had final approval of the manuscript for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.N. reports personal fees from Sobi and sponsorship from Bayer, CSL Behring, and Sanofi. A.K. reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sobi, and Takeda; advisory board participation for CSL Behring, Roche, Sobi, and Takeda; and lectures for CSL Behring, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda. A.S. reports research support from Agios, BioMarin, Bioverativ (a Sanofi company), Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech, Glover Blood Therapeutics, Kedrion Biopharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, OPKO Biologics, Pfizer, Prometic BioTherapeutics, Sangamo, Sigilon Therapeutics, and Takeda; speaker fees from Genentech and Novo Nordisk; and advisory board fees from Bioverativ, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Sangamo, and Sigilon Therapeutics (all support and fees paid to the institution). A.R. reports advisory board participation for BioMarin, CSL Behring, LFB, Octapharma, Roche, and Sobi and research funding from CSL Behring and Roche. M. Recht reports grants from BioMarin, Bioverativ, Genentech, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Spark Therapeutics, Takeda, and uniQure and personal fees from CSL Behring, Genentech, Kedrion, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Takeda, and uniQure. M. Ragni reports research funding from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inc., American Thrombosis Hemostasis Network, Baxalta/Takeda, BioMarin, Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Genentech/Roche, OPKO Biologics, Sangamo Therapeutics, Inc., Spark Therapeutics, and Vascular Medicine Institute; advisory board participation for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Baxalta/Takeda, BioMarin, Bioverativ, and Spark Therapeutics; consultancy for Sangamo Therapeutics, Inc.; and committee work for American Thrombosis Hemostasis Network. J.C. reports study sponsorship from Bioverativ (paid to the institution); research funding from CSL Behring and Shire/Takeda; personal fees from Bioverativ, CSL Behring, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi; hemophilia treatment center funding and equipment support from Pfizer; and advisory board participation for BioMarin, CSL Behring, Freeline (paid to institute), Roche, and Shire/Takeda. S.G., S.M., and D.J. are employees of Sanofi. B.W. is an employee of Sobi. K.F. reports speaker’s fees from Bayer, Baxter/Shire, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, and Sobi/Biogen; consultancy for Bayer, Baxter, Biogen, CSL Behring, Freeline, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, and Sobi; research support from Bayer, Baxter/Shire, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer; and fees from Biogen (paid to institutition). R.L. reports personal fees from Bayer, CSL Behring, Grifols, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Roche, Shire/Takeda, and Sobi.

References

Author notes

Data sharing statement: qualified researchers may request access to data and related study documents. Patient-level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Additional details on Sanofi data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.