Key Points

A source of treatment refractoriness in immune cytopenias appears to be residual CD138/38-positive lymphocyte populations.

A short course of daratumumab is a novel treatment of refractory thrombocytopenia after failure of standard treatment options.

Introduction

Refractory immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) occurs in 100 cases per million annually,1 and can lead to significant complications including life-threatening bleeding. Platelet refractoriness in posttransplant patients is frequently attributed to donor-recipient antigen mismatch. A source of treatment refractoriness in immune cytopenias appears to be residual CD138/38-positive lymphocyte populations.2,3 In particular, the persistence of the recipient’s plasma cells may lead to prolonged refractory thrombocytopenia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).4 Alternatively, autoimmune cytopenia can occur in the setting of incomplete immune recovery post-HSCT, leading to immune dysregulation.5,6 Daratumumab, an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody, was first reported as a successful treatment of refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia that developed in a child after HSCT. Here we report on a sustained 16-month complete response to daratumumab for prolonged severe thrombocytopenia after reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) HSCT in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Case description

A 60-year-old white man with high-risk MDS underwent RIC-HSCT with total lymphoid irradiation-antithymocyte globulin conditioning using a peripheral blood stem cell graft (CD34+ cell/kg dose: 5.4 × 10E6/kg; CD3+ cell/kg dose: 1.9 × 10E8/kg) from a fully HLA-matched unrelated male donor (donor/recipient ABO status: O+/O+; donor/recipient cytomegalovirus serologic status: positive/negative; recipient Epstein-Barr virus [EBV] serologic status: positive). The patient had mild thrombocytopenia before transplant (>100 × 109/L) as a result of MDS, and had never received platelet transfusions. The patient had an uncomplicated early posttransplant course, achieving white cell recovery on day 12 and platelet recovery to 100 × 109/L on day 18. His peripheral blood chimerism on day 30 showed full donor origin (whole blood, 98%; CD3, 96%; CD15, 95%; CD19, 98%; CD56, 95%).

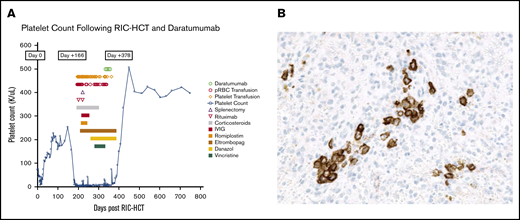

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. The patient developed acute skin GVHD, which was treated to resolution with steroids. While receiving tapering corticosteroid therapy for GVHD, he developed an abrupt decline in platelet count from 156 × 109/L on day 152 to 9 × 109/L on day 166 without evidence for active GVHD. Although this was initially attributed to simultaneous EBV and cytomegalovirus reactivations, severe thrombocytopenia persisted despite viral load clearance. An extensive work-up for other etiologies of thrombocytopenia was negative, and he had no evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy or splenomegaly. Repeated bone marrow biopsies were normal, including adequate megakaryocytopoiesis and no evidence of MDS. Platelet-associated antibody testing and platelet antigen genotyping were inconclusive for autoimmune vs alloimmune etiology. However, during this episode at 5 months post-HSCT, there was a transient drop in CD19 chimerism from 98% to 89%, and absolute lymphocyte count was low. Testing for platelet HLA antibodies showed a calculated panel reactive antibody of 31% and unsatisfactory corrected count increment despite transfusion of HLA-compatible platelet units. The patient experienced prolonged severe thrombocytopenia for more than 26 weeks with platelet count less than 5 × 109/L for 22 weeks and only above 10 × 109/L on 6 occasions, despite multiple platelet transfusions (Figure 1A). Potentially responsible medications were discontinued serially (including tacrolimus) without improvement in platelet count. Platelet-associated antibody testing for drug-induced ITP, against common agents and against tacrolimus, were negative (Versiti Blood Center of Wisconsin Diagnostic Laboratories). Therapy included high-dose corticosteroids, vincristine, high-dose immune globulin, rituximab, plasma exchange, splenectomy, romiplostim 10 μg/kg per week, eltrombopag 100 to 150 mg daily for more than 24 weeks, and danazol 400 mg daily without any significant clinical improvement in platelet counts. The patient developed grade 3 neuropathy after vincristine. A syk-inhibitor, fostamatinib, was considered, but was not commercially available. The patient experienced recurrent episodes of severe bleeding requiring a total of 133 single-donor apheresis platelet units. Eltrombopag and danazol were deemed ineffective and tapered to discontinuation. CD38+ cells were present in spleen and marrow by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1B). The donor or recipient origin of the plasma cells could not be determined.

Platelet count trends and immunohistochemistry staining. (A) Patient’s platelet count after ITP treatment (including daratumumab) and transfusion needs. (B) CD138 immunohistochemical staining showed increased plasma cells in a spleen section.

Platelet count trends and immunohistochemistry staining. (A) Patient’s platelet count after ITP treatment (including daratumumab) and transfusion needs. (B) CD138 immunohistochemical staining showed increased plasma cells in a spleen section.

As a result of retinal hemorrhages with vision loss, hemorrhagic cystitis, and epistaxis, daratumumab therapy was initiated at the standard dose of 16 mg/kg per week IV for 4 infusions. Four weeks after the last dose of daratumumab, the patient’s platelet count increased to 91 × 109/L. Platelet count normalized to 150 × 109/L in week 5 (day 383 posttransplant). Absolute lymphocyte count improved to normal range. The patient is clinically doing well, other than having developed mild chronic gastrointestinal GVHD, which was managed successfully with low-dose corticosteroids. He is in remission from MDS.

Methods

The methodology combined retrospective chart review as well as prospective data collection after the first daratumumab infusion. The patient gave informed consent for off-label use of the medication and publication of the case findings. Institutional review board approval for data collection was obtained. Daratumumab is manufactured by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies (Raritan, NJ), and was obtained commercially.

Results and discussion

Daratumumab, a human immunoglobulin G1κ monoclonal antibody targeting CD38, was approved for treatment of multiple myeloma in 2015. Our hypothesis, based on previous publications,4,6-8 was that platelets from donor-derived engrafted megakaryocytes were targets of antiplatelet antibodies produced by retained recipient plasma cells. The transient drop in CD19 donor chimerism during this episode could support the theory that residual host B cells mediated this cytopenia. However, an autoimmune etiology of thrombocytopenia could not be excluded, as this event occurred in the setting of possible immune dysregulation triggered by infection with cytomegalovirus/EBV reactivation or prior exposure to the lymphodepleting agent anti-thymocyte globulin.9 Although an alloimmune vs autoimmune antibody etiology could not be distinguished, the rationale for using daratumumab in this very refractory case was to target the antibody-producing plasma cells after RIC conditioning.

This is a report of a sustained complete remission in a patient with refractory ITP after failure of all approved therapies. This off-label use of daratumumab was justified by the scientific rationale and dire medical need. Although established alternative approaches directed to plasma cells, such as bortezomib,8,10 were considered, the safety profile and mechanism of daratumumab were favored. We administered daratumumab 6 months after rituximab, which allowed a wash-out period, as the half-life of rituximab is 22 days. The number of daratumumab doses administered was similar to other published cases with posttransplant cytopenias5-7,11 and took into account our risk assessment for disabling and life-threatening adverse effects based on the published experience in multiple myeloma and amyloidosis.

Since we treated our patient,12 5 additional cases of refractory autoimmune cytopenias responsive to daratumumab have been reported,6,7,11 bringing the total number of known cases to 7 (Table 1). The dose of daratumumab was 16 mg/kg in all cases, and the number of weekly doses ranged from 4 to 11. The time to response ranged from 1 week to 3 months from the last dose of daratumumab. B-cell recovery is noted in 4 patients, including ours, and occurred at 2.5, 6.5, 7.5, and 12 months from therapy.

Summary of the 7 reported patients with posttransplant cytopenias successfully treated with daratumumab

| Patient . | Diagnosis . | Conditioning . | HSCT Source . | Cytopenia onset after HSCT; daratumumab infusion timing . | Treatment before daratumumab . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case report (PRCA)1 | MDS | Bu/Flu | MUD | First weeks; day 390 | High-dose steroids/rituximab/darbepoetin |

| Case report (AIHA)*2 | B ALL | Bu/Flu/Clo/alemtuzumab | MUD | Day 116; day 619 | MPN/rituximab/bortezomib/MMF/sirolimus/alemtuzumab/ibrutinib |

| XLT/WAS | Treo/Flu/Thio/alemtuzumab | MUD | Day 138; day 403 | Prednisolone/rituximab/plasmapheresis/MMF bortezomib | |

| DNA-ligase IV deficiency | Flu/Cy/alemtuzumab | MRD | Day 286; day 619 | Steroids/MMF/rituximab/ bortezomib/eculizumab | |

| Case report (Evans syndrome)3 | Severe aplastic anemia | Flu/Cy/alemtuzumab | MRD | 11 mo; ∼day 425 | Prednisolone/cyclosporine/IVIG/eltrombopag/rituximab/ romiplostim/bortezomib |

| Case report (AIHA)4 | B ALL | Bu/Flu/Clo/alemtuzumab | Mismatched unrelated donor | 1 mo; NA | MPN/rituximab/bortezomib/alemtuzumab/MMF/sirolimus/ibrutinib |

| Our patient | MDS | ATG/TLI | MUD | Day 152; ∼12 mo | MPN/vincristine/IVIG/rituximab/plasma exchange/splenectomy romiplostim/eltrombopag/danazol |

| Patient . | Diagnosis . | Conditioning . | HSCT Source . | Cytopenia onset after HSCT; daratumumab infusion timing . | Treatment before daratumumab . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case report (PRCA)1 | MDS | Bu/Flu | MUD | First weeks; day 390 | High-dose steroids/rituximab/darbepoetin |

| Case report (AIHA)*2 | B ALL | Bu/Flu/Clo/alemtuzumab | MUD | Day 116; day 619 | MPN/rituximab/bortezomib/MMF/sirolimus/alemtuzumab/ibrutinib |

| XLT/WAS | Treo/Flu/Thio/alemtuzumab | MUD | Day 138; day 403 | Prednisolone/rituximab/plasmapheresis/MMF bortezomib | |

| DNA-ligase IV deficiency | Flu/Cy/alemtuzumab | MRD | Day 286; day 619 | Steroids/MMF/rituximab/ bortezomib/eculizumab | |

| Case report (Evans syndrome)3 | Severe aplastic anemia | Flu/Cy/alemtuzumab | MRD | 11 mo; ∼day 425 | Prednisolone/cyclosporine/IVIG/eltrombopag/rituximab/ romiplostim/bortezomib |

| Case report (AIHA)4 | B ALL | Bu/Flu/Clo/alemtuzumab | Mismatched unrelated donor | 1 mo; NA | MPN/rituximab/bortezomib/alemtuzumab/MMF/sirolimus/ibrutinib |

| Our patient | MDS | ATG/TLI | MUD | Day 152; ∼12 mo | MPN/vincristine/IVIG/rituximab/plasma exchange/splenectomy romiplostim/eltrombopag/danazol |

AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; B ALL, B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia; Bu, busulfan; Clo, clofarabine; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPN, methylprednisolone; MRD, matched related donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; NA, not available; Thio, thiotepa; PRCA, pure red cell aplasia; TLI, total lymphoid irradiation; Treo, treosulfan; WAS, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome; XLT, X-linked thrombocytopenia.

Three patients included in this case report.

At 16 months postdaratumumab, our patient shows no signs of bleeding. To date, platelets are produced in the supranormal range. He had transient mild lymphopenia during daratumumab therapy, with mild hypogammaglobulinemia the only detectable toxicity. Immune globulin replacement therapy was discontinued 9 months postdaratumumab.

Further investigation is needed to elucidate the mechanism of refractory ITP in posttransplant patients with RIC, whether alloimmune or autoimmune, and the effect of daratumumab treatment on immune cell and cytokine populations that are proposed to be involved.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the Department of Pathology and Transfusion Medicine for providing the slide image. They extend their gratitude to the patient for allowing us to report this interesting case, and to the Bone Marrow Transplant nursing staff. The authors thank Judith Shizuru for her critical review of this manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.M., S.A., and B.A.M. provided concept and design; Y.M., A.E., S.A., and B.A.M. wrote, reviewed, and/or revised the manuscript; Y.M., A.E., R.G., F.S., S.A., and B.A.M. acquired data (managed patients, provided facilities); and Y.M., A.E., R.P.J., W.K., S.A., and B.A.M. provided administrative, technical, or material support.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yazan Migdady, Stanford University, 300 Pasteur Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail address: yazan.migdady@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

Data available via e-mail to the corresponding author, Yazan Migdady (yazan.migdady@nih.gov).