Key Points

Outcomes of patients with R/R MCL failing CAR-T therapy are particularly poor, without standardized salvage option.

Bispecific antibodies appear to be a promising therapeutic option, offering durable responses compared to chemotherapy and targeted therapy.

Visual Abstract

Brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel) is the anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor CAR T-cell (CAR-T) therapy approved for the treatment of relapsed/refractory (R/R) mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Our study, conducted in the scope of the French DESCAR-T registry, aimed to analyze outcomes of MCL after brexu-cel failure. In the DESCAR-T registry, 178 patients with R/R MCL received brexu-cel. After a median follow-up (FU) of 14.5 months, 61 experienced failures. This study analyzes post– CAR-T failure progression-free survival (PFS2) and overall survival (OS2), according to clinical characteristics and salvage treatments. At infusion, 36% of patients had a high MCL International Prognostic Index score, 76.2% a Ki-67 index of ≥30%, 30.2% a TP53 mutation, and 31.6% a blastoid variant. After a median FU of 15 months following failure, median OS2 and PFS2 were 5.8 and 1.8 months, respectively. Patients experiencing early failure (<3 months) had a median OS2 of 1.8 months, compared with 6.7 and 9 months for those relapsing within 3 to 6 and after 6 months, respectively. Forty-nine patients received salvage therapy: 16 lenalidomide with/without rituximab (Len/R2), 13 immunochemotherapy (ICT), 8 Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor with/without venetoclax (BTKi/Ven), 7 bispecific T-cell engagers (TCEs), 3 another targeted therapy, and 2 received radiation. Overall, post salvage response rate (ORR) was 20%. One-year OS2 was 36% for patients treated with Len/R2 and ICT, 57% for TCEs, and 0% for other types of salvage. Notably, none of the TCE responders have relapsed to date (duration of response : 100%). Our series highlights the poor outcomes of patients with MCL after CAR-T failure and suggests a potential benefit of bispecific antibodies in this population.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has become a key standard of care in therapeutic strategies for relapsed/refractory (R/R) B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.1-3 The CD19-directed CAR-T cell therapy brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel) is approved in France since 2020 for the management of R/R mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) after at least 2 previous systemic treatments including a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis), based on efficacy data from the phase 2 ZUMA-2 trial.4 In this trial, Wang et al reported an overall response rate (ORR) and complete response rate of 93% and 67%, respectively, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 26 months, and a median duration of response (DOR) of 28 months. Similar results were observed in the expanded access ZUMA-18 trial,5 and with lisocabtagene maraleucel in the TRANSCEND trial.6

Real-world (RW) series7-12 report superposable response rates, however, there is variability in the DOR and no plateau on survival curves, highlighting a continuous pattern of relapse. In these RW series, 1-year PFS ranged from 45.6%8 to 62%.10,12 In the French DESCAR-T (Dispositif d’Enregistrement et de Suivi des CAR-T) registry, designed by the Lymphoma Study Association to collect RW data on commercial CAR-T cells,8 Herbaux et al described after a median follow-up (FU) of 12.2 months a median PFS of 9 months and a 1-year PFS of 45.6%. This heterogeneity in outcomes reported in prospective vs retrospective series (supplemental Table 1) is likely due to the variation in the risk profile of the patient population studied, emphasized by the need of a bridging strategy or not. Indeed, in the ZUMA-2 study, among 68 patients who received treatment, 25 (37%) required bridging therapy, restricted to corticosteroids and BTKis. In contrast, RW studies report a significantly higher use of bridging, composed of a broader range of regimens (immunochemotherapy [ICT], BTKis [both covalent and noncovalent], or other targeted agents), from 68% in the US database,9 to 83% in the French DESCAR-T,8 consistent with the greater proportion of high-risk disease features at inclusion.

Overall, CAR-T failure is not a rare event for R/R MCL, but current data focusing on outcome and therapeutic options for these patients are lacking in the literature. The aim of this study was to describe the outcome of MCL patients registered in DESCAR-T who progressed or relapsed after brexu-cel infusion and to investigate the relationship between treatment strategies at failure and outcomes.

Methods

Study population

The DESCAR-T registry13 is a French national, multicenter database designed to collect RW data on patients with hematologic malignancies; eligible for, and treated with, commercial CAR-T therapies validated by a multidisciplinary tumor board in an accredited CAR-T center. All patients or their representatives provided informed consent to noninterventional use of personal data before inclusion in the DESCAR-T registry (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04328298).

Between 2019 and 2024, 217 patients diagnosed with R/R MCL and in intent to treatment with brexu-cel were enrolled in the DESCAR-T registry. Of these, 186 (86%) patients ultimately received infusion, and 178 had an evaluable response (8 patients were excluded due to missing data). Patients were included in this analysis if they had experienced a failure (defined as relapse, progression, or refractory disease) after brexu-cel (relapse set, see study flowchart; supplemental Figure 1). Progression was assessed by the treating physician.

End points

Primary end points were overall survival after failure (OS2) defined as the time from treatment failure to death from any cause, and PFS after failure (PFS2) defined as the time from brexu-cel failure to salvage progression. Secondary end points included the description of baseline characteristics, an in-depth review of treatments proposed at failure, response, and outcomes based on salvage treatment groups, and an analysis of prognostic factors associated with survival.

Salvage treatments were classified into 6 groups as, lenalidomide with or without rituximab (Len/R2), BTKis with or without venetoclax (BTKi/Ven), chemotherapy with or without anti-CD20 (ICT/CT), CD3-CD20 bispecific antibodies/T-cell engagers (TCEs), other targeted therapies (Protein Kinase B [AKT] inhibitors and Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 inhibitors [EZH-2] inhibitors), and radiation.

Statistical analysis

Survival analyses were performed on patients with at least 1 follow-up visit or those who had died before FU (60/61), PFS2 was assessed in the salvage cohort (49/61). Quantitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, whereas qualitative variables were expressed as mean, standard deviation, median, and range.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival probabilities (OS2 and PFS2) at any time point, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate models were conducted to identify prognostic factors associated with OS2 and PFS2. We first analyzed the clinical characteristics associated with OS2 in the entire post–brexu-cel failure population (N = 61), and then the impact of salvage and clinical characteristics on outcome (OS2 or PFS2) among patients who received salvaged therapy (N = 49). All variables that were statistically associated with survival or relapse in the univariate analysis (P value < .05) were initially included in the multivariate analysis. Multivariate model was performed only on patients for whom complete data were available. A backward selection model was used to perform the multivariate analysis: after several successive steps, only variables that remained statistically associated (P < .05) based on the self-exclusion of nonsignificant variables were retained in the final model. Considering the exclusion of variables that were not statistically associated, the multivariate model was finally performed on 49 of 61 patients for the entire post–brexu-cel failure population, 42 of 49 patients for PFS2, and 44 of 49 for OS2 in the salvaged patient population. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

Results

After a median FU of 14.5 months after infusion, 154 of 178 patients who received infusion (86.5%) were responders, including 134 (75.3%) in complete response (CR) and 20 (11.2%) in partial response (PR). Eighteen patients (9.7%) died without relapse: 12 died from acute toxicity (2 from cytokine release syndrome and 10 from infection), 3 died from late toxicity (with 2 due to myelodysplastic syndrome and 1 from infection), and cause of death was missing for 3, without progression documented. Ultimately, 61 (34%) patients experienced failure after brexu-cel. Subsequent analyses will focus exclusively on this population (N = 61; see supplemental Figure 1).

Demographic data of patients with failure after brexu-cel

Characteristics at time of the CAR-T medical tumor board are presented in Table 1. Briefly, 54 of 61 patients (88.5%) were male, with a median age of 66 years (range, 39-83). Nineteen patients (19/53 [36%,]) had a high MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI), and 32 patients (32/42 [76%]) had a Ki-67 level of >30%. TP53 mutational status was available for 43 patients, of whom 13 (30%) had mutations. A blastoid variant was reported in 18 of 57 (31.6%). Before brexu-cel infusion, patients had received a median of 3 previous lines of treatment (range, 2-8) including ICT with rituximab for all of them, a BTKi for 59 of 61 (97%), and 27 of 61 (44%) underwent stem cell transplantation, including autologous transplantation in 25 patients and allogeneic transplantation in 2 patients (supplemental Table 2). Notably, 37 of 58 (63.8%) were refractory to their previous lines of treatment, and 51 of 60 (83%) had experienced progression within 2 years of first-line treatment (POD24).

Baseline characteristics at CAR-T MTB of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure (relapsed set)

| Baseline Characteristics . | MCL relapsed set, N = 61 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 54 | 88.5% |

| Age, median (min; max) | 66.0 (39; 83) | |

| Age ≥65 years | 35 | 57.4% |

| Age >75 years | 2 | 3.3% |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0-1 | 54/57 | 94.7% |

| ≥2 | 3/57 | 5.3% |

| Bulk disease >5 cm | 34/59 | 57.6% |

| MIPI risk | ||

| Low risk (<5.7) | 13/53 | 24.5% |

| Intermediate risk (5.7-6.2) | 21/53 | 39.6% |

| High risk (≥6.2) | 19/53 | 35.8% |

| Ki-67 of ≥30% | 32/42 | 76.2% |

| Blastoid variant | 18/57 | 31.6% |

| TP53 mutation | 13/43 | 30.2% |

| LDH greater than normal | 35/59 | 59.3% |

| CRP of >30 mg/L | 16/60 | 26.2% |

| Number of previous lines | ||

| Median (min; max) 3 (2; 8) | ||

| Detail of previous lines | ||

| 2 | 16 | 26.2% |

| 3 | 26 | 42.6% |

| ≥4 | 19 | 31% |

| Refractory status∗ | 37/58 | 63.8% |

| POD24 status positive | 51/60 | 83% |

| Progressive disease after bridge† | 25/57 | 44.5% |

| Baseline Characteristics . | MCL relapsed set, N = 61 . | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 54 | 88.5% |

| Age, median (min; max) | 66.0 (39; 83) | |

| Age ≥65 years | 35 | 57.4% |

| Age >75 years | 2 | 3.3% |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0-1 | 54/57 | 94.7% |

| ≥2 | 3/57 | 5.3% |

| Bulk disease >5 cm | 34/59 | 57.6% |

| MIPI risk | ||

| Low risk (<5.7) | 13/53 | 24.5% |

| Intermediate risk (5.7-6.2) | 21/53 | 39.6% |

| High risk (≥6.2) | 19/53 | 35.8% |

| Ki-67 of ≥30% | 32/42 | 76.2% |

| Blastoid variant | 18/57 | 31.6% |

| TP53 mutation | 13/43 | 30.2% |

| LDH greater than normal | 35/59 | 59.3% |

| CRP of >30 mg/L | 16/60 | 26.2% |

| Number of previous lines | ||

| Median (min; max) 3 (2; 8) | ||

| Detail of previous lines | ||

| 2 | 16 | 26.2% |

| 3 | 26 | 42.6% |

| ≥4 | 19 | 31% |

| Refractory status∗ | 37/58 | 63.8% |

| POD24 status positive | 51/60 | 83% |

| Progressive disease after bridge† | 25/57 | 44.5% |

CRP, C-reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MTB, medical tumor board.

To their previous lines of treatment: at time of CAR-T decision.

At time of CAR-T infusion.

A bridge had been applied to most patients (56/61 [92%]), predominantly using ICT/CT (see supplemental Table 3 for bridging and response to bridging). At the time of brexu-cel infusion, 20 patients (36%) were in response to this bridge, including 3 patients (5.4%) with CR and 17 (30.4%) in PR, whereas 25 patients (45%) were received infusion while in progressive disease.

Timing of relapse and post–CAR-T failure outcome

The best response rate seen at the first evaluation (M1) after brexu-cel was 82% (50/61) including 28 CR (46%) and 22 PR (36%), whereas 9 (14.6%) had a CAR-T primary refractory disease (including 1 death due to progression), and 2 were not evaluated (3.3%). The median time to failure was 4.5 months; 17 patients (28%) experienced failure within the first 3 months, 25 (42%) between 3 and 6 months, and 18 (30%) after 6 months.

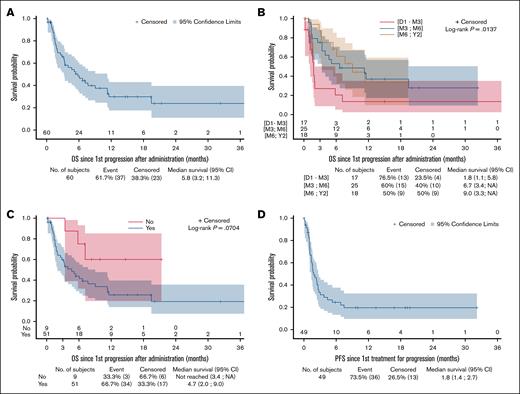

After a median FU of 15 months after brexu-cel failure, the median OS2 was 5.8 months (95% CI, 3.2-11.3; Figure 1A), and 6-month and 12-month OS2 rates was estimated at 48.4% (95% CI, 34.5-60.9) and 29.8% (95% CI, 17.5-43.2), respectively. OS was significantly associated with the timing of relapse; patients who experienced failure within 3 months, having a median OS2 of 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.1-5.8), significantly shorter than those who relapsed between 3 and 6 months and beyond 6 months (6.7 months; 95% CI, 3.4 to not applicable [NA] and 9 months [95% CI, 3.3 to NA], respectively; P = .0137; Figure 1B). Patients with a history of POD24 (N = 51/60 [85%]) had a median OS2 of 4.7 months (95% CI, 2-9), that tended to be shorter than that of patients with later progression (N = 9/60 [15%]) after their first lines (median OS2 not reached 95% CI, 3.4 to NA) with an estimated 1-year OS2 of 60% (95 % CI, 19.5-85.2; P = .0704; Figure 1C).

Outcomes of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure to salvage progression. (A) OS2 of relapsed set (N = 60). (B) OS2 according to timing of failure of relapsed set. (C) OS2 according to POD24 status of relapsed set. (D) PFS2 of treated set (N = 49).

Outcomes of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure to salvage progression. (A) OS2 of relapsed set (N = 60). (B) OS2 according to timing of failure of relapsed set. (C) OS2 according to POD24 status of relapsed set. (D) PFS2 of treated set (N = 49).

Finally, a total of 39 patients died, lymphoma being the leading cause (35/39 [90%]). For the remaining 4 patients, cause of death was infections (1 cerebral toxoplasmosis, 1 aspergillosis, and 2 COVID-19).

Salvage strategies and post–brexu-cel failure outcomes

Salvage information were available for 60 of 61 patients: 49 (82%) of whom received an active treatment; whereas for 11 (18%), palliative care was applied directly. Among the 49 patients who received salvage therapy, 16 patients (33%) received Len/R2, 13 (27%) CT/ICT, 8 (16%) BTKi/Ven, 7 (14%) TCEs (all glofitamab), 3 (6%) other targeted treatment, and 2 (4%) received radiation. Overall, 10 patients (20.4%) achieved a response, including 9 CR and 1 PR (Table 2). The ORR/CR was 18.8%/18.8% for patients treated by Len/R2, 23%/15% after CT/ICT, 43%/43% with TCEs, and 50%/50% after radiation. None of the patients treated with BTKis (all noncovalent; 7 received ibrutinib, including 5 in combination with venetoclax; and 1 received acalabrutinib alone) and other targeted therapies responded.

Outcomes of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure according to salvage therapy

| . | Len/R2 . | CT/ICT . | BTKi/Ven . | TCE . | Other targeted therapy . | Radiation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | ||||||

| ORR, n (%) | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0 | 3 (42.9%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| CR, n (%) | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 | 3 (42.9%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| PR, n (%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PFS | ||||||

| Median (95% CI), mo | 2 (0.7-4.4) | 1.1 (0.7-7.5) | 1.7 (1.1-3.1) | 1.5 (0.9-NA) | 2.7 (2.4-NA) | NR (2.4-NR) |

| 6 months (95% CI), % | 23.4 (5.7-47.9) | 30.8 (9.5-55.4) | 0 | 42.9 (9.8-73.4) | 0 | 50 (0.6-91) |

| 12 months (95% CI), % | 15.6 (2.5-39.1) | 23.1 (5.6-47.5) | 0 | 42.9 (9.8-73.4) | 0 | 50 (0.6-91) |

| OS | ||||||

| Median (95% CI), mo | 6.7 (2- NA) | 5.8 (1.5-NA) | 2.8 (1.4-4) | NR (3.3-NA) | 9.6 (7.7-NA) | 11.3 (NA-NA) |

| 6 months (95% CI), % | 44.9 (17.7-69) | 56.3 (27.2-77.6) | 0 | 71.4 (25.8-92) | 0 | 100 (NA-NA) |

| 12 months (95% CI), % | 36.2 (10.8-62.8) | 35.9 (11.7-61.3) | 0 | 57.1 (17.2-83.7) | 0 | 0 |

| . | Len/R2 . | CT/ICT . | BTKi/Ven . | TCE . | Other targeted therapy . | Radiation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | ||||||

| ORR, n (%) | 3 (18.8%) | 3 (23.1%) | 0 | 3 (42.9%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| CR, n (%) | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (15.4%) | 0 | 3 (42.9%) | 0 | 1 (50%) |

| PR, n (%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PFS | ||||||

| Median (95% CI), mo | 2 (0.7-4.4) | 1.1 (0.7-7.5) | 1.7 (1.1-3.1) | 1.5 (0.9-NA) | 2.7 (2.4-NA) | NR (2.4-NR) |

| 6 months (95% CI), % | 23.4 (5.7-47.9) | 30.8 (9.5-55.4) | 0 | 42.9 (9.8-73.4) | 0 | 50 (0.6-91) |

| 12 months (95% CI), % | 15.6 (2.5-39.1) | 23.1 (5.6-47.5) | 0 | 42.9 (9.8-73.4) | 0 | 50 (0.6-91) |

| OS | ||||||

| Median (95% CI), mo | 6.7 (2- NA) | 5.8 (1.5-NA) | 2.8 (1.4-4) | NR (3.3-NA) | 9.6 (7.7-NA) | 11.3 (NA-NA) |

| 6 months (95% CI), % | 44.9 (17.7-69) | 56.3 (27.2-77.6) | 0 | 71.4 (25.8-92) | 0 | 100 (NA-NA) |

| 12 months (95% CI), % | 36.2 (10.8-62.8) | 35.9 (11.7-61.3) | 0 | 57.1 (17.2-83.7) | 0 | 0 |

N, number; NA, not applicable; NR, not reached.

After a median FU of 15 months after salvage, the median PFS2 was 1.8 months (95% CI, 1.4-2.7; Figure 1D), with 6-month and 12-month PFS2 rates estimated at 24.6% (95% CI, 13.2-37.7) and 19.7% (95% CI, 9.5-32.4), respectively. PFS2 at 1 year was 15.6% (95% CI, 2.5-39.1) for patients treated with Len/R2, 23.1% (95% CI, 5.6-47.5) for patients treated with CT/ICT, 42.9% (95% CI, 9.8-73.4) for those receiving TCEs, and 50% (95% CI, 0.6-91) for those treated with radiation therapy. Of note, none of the TCE responders have relapsed to date (1-year DOR was 100%), although none presented a blastoid variants, nor high Ki-67 at diagnosis, 2 had a high MIPI score and 2 had a history of POD24 disease. Estimated 1-year OS2 was 36% for patients treated with Len/R2 (95% CI, 10.8-62.8) and CT/ICT (95% CI, 11.7-61.3); 57.1% (95% CI, 17.2-83.7) for those treated with TCEs; and 0% for patients treated with BTKi/Ven, other targeted therapies, and radiation (see Table 2).

Prognostics factors

We aimed to identify prognostic factors associated with an increased risk of relapse or mortality. In the overall population (N = 61), the univariate analysis identified significant associations between OS2 and a high MIPI score (hazard ratio [HR], 4.850; 95% CI, 1.708-13.773; P = .003), refractory status to bridging therapy (HR, 3.743; 95% CI, 1.834-7.640; P = .0003) and with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of ≥2 at infusion (HR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.232-5.490; P = .0122). Conversely, no statistically significant association was observed for the presence of a TP53 mutation, the presence of a blastoid variant, or a Ki-67 index of >30%, although low numbers might induce bias. The initial multivariate model included these 3 variables, and after a backward selection, the absence of response after bridging therapy (HR, 5.637; 95% CI, 2.403-13.223; P ≤ .001) and ECOG PS of ≥2 at infusion (HR, 2.496; 95% CI, 1.143-5.448; P ≤ .0217) remained statistically associated with worse OS2 (Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors associated with survival (OS2) of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure, relapsed set

| Prognostic factors . | Univariate model . | MCL relapsed set, N = 61 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate model∗ . | ||||||

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age at infusion | 1.018 | 0.984-1.054 | .2971 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 1.025 | 0.481-2.184 | .9489 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.922 | 0.467-1.818 | .8138 | |||

| Not responder to bridging | 3.743 | 1.834-7.640 | .0003 | 5.637 | 2.403-13.223 | < .0001 |

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.790 | 0.168-3.725 | .7663 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.312 | 0.590-2.918 | .5048 | |||

| Ki-67 (%) ≥30% | 3.235 | 0.958-10.918 | .0586 | |||

| POD24 | 0.352 | 0.108-1.150 | .0840 | |||

| Bulky disease | 1.406 | 0.708-2.794 | .3305 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 4.850 | 1.708-13.773 | .0030 | |||

| ECOG PS at infusion ≥2 | 2.600 | 1.232-5.490 | .0122 | 2.496 | 1.143-5.448 | .0217 |

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion more than the upper limit | 1.325 | 0.668-2.629 | .4205 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 1.718 | 0.856-3.450 | .1278 | |||

| CRS | 1.765 | 0.685-4.547 | .2390 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.562 | 0.810-3.014 | .1835 | |||

| Prognostic factors . | Univariate model . | MCL relapsed set, N = 61 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate model∗ . | ||||||

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age at infusion | 1.018 | 0.984-1.054 | .2971 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 1.025 | 0.481-2.184 | .9489 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.922 | 0.467-1.818 | .8138 | |||

| Not responder to bridging | 3.743 | 1.834-7.640 | .0003 | 5.637 | 2.403-13.223 | < .0001 |

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.790 | 0.168-3.725 | .7663 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.312 | 0.590-2.918 | .5048 | |||

| Ki-67 (%) ≥30% | 3.235 | 0.958-10.918 | .0586 | |||

| POD24 | 0.352 | 0.108-1.150 | .0840 | |||

| Bulky disease | 1.406 | 0.708-2.794 | .3305 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 4.850 | 1.708-13.773 | .0030 | |||

| ECOG PS at infusion ≥2 | 2.600 | 1.232-5.490 | .0122 | 2.496 | 1.143-5.448 | .0217 |

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion more than the upper limit | 1.325 | 0.668-2.629 | .4205 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 1.718 | 0.856-3.450 | .1278 | |||

| CRS | 1.765 | 0.685-4.547 | .2390 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.562 | 0.810-3.014 | .1835 | |||

CRS, cytokine release syndrome; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Multivariate analysis was performed on 49 of 61 patients with available data.

Within the population of 49 patients who received a salvage, in univariate analysis, a high MIPI score at infusion (HR, 4.025; 95% CI, 1.307-12.395; P = .0152), and the presence of the blastoid variant (HR, 2.186; 95% CI, 1.074-4.452; P = .031) were the 2 factors significantly associated with shorter PFS2. Treatment with TCEs was not (HR, 0.598; 95% CI, 0.210-1.701; P = .3351). In the multivariate model using a backward selection model, both the presence of a blastoid variant (HR, 2.199; 95% CI, 1.010-4.791; P = .0472) and a high MIPI risk at infusion (HR, 3.268; 95% CI, 1.036-10.305; P = .0433) remained associated with an increased risk of postsalvage failure (see Table 4, multivariate analysis including 42/49 available patients). Finally, within this population (N = 49), univariate models identified the absence of response after bridging therapy (HR, 3.407; 95% CI, 1.550-7.487; P = .0023) and a high MIPI risk at infusion (HR, 6.257; 95% CI, 1.922-20.367; P = .0023) as factors significantly associated with shorter OS2. In the multivariate model including these 2 variables, both lack of response to bridging therapy (HR, 3.576; 95% CI, 1.472-8.686; P = .0049) and high MIPI score (HR, 4.095; 95% CI, 1.207-13.897; P = .0238) remained independently associated with shorter OS2 (see Table 4).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors associated with relapse (PF2) and survival (OS2) of R/R MCL after brexu-cel failure

| Prognostic factors . | Univariate model . | MCL treated patients, N = 49 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate model∗ . | ||||||

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| PFS2 | ||||||

| Age at infusion | 0.990 | 0.958-1.023 | .5557 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 0.657 | 0.306-1.407 | .2792 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.896 | 0.451-1.776 | .7523 | |||

| Nonresponder to bridging | 1.866 | 0.930-3.745 | .0792 | |||

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.467 | 0.125-1.749 | .2587 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.206 | 0.556-2.617 | .6360 | |||

| Bulk disease | 0.818 | 0.401-1.667 | .5802 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 4.025 | 1.307-12.395 | .0152 | 3.268 | 1.036-10.305 | .0433 |

| ECOG PS in class at infusion ≥2 | 1.306 | 0.585-2.912 | .5147 | |||

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion more than the upper limit | 1.015 | 0.499-2.066 | .9666 | |||

| POD24 | 0.442 | 0.156-1.256 | .1255 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 2.186 | 1.074-4.452 | .0311 | 2.199 | 1.010-4.791 | .0472 |

| CRS | 0.625 | 0.258-1.514 | .2979 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.246 | 0.643-2.412 | .5146 | |||

| TCE salvage treatment vs others | 0.598 | 0.210-1.701 | .3351 | |||

| OS2 | ||||||

| Age at infusion | 1.003 | 0.965-1.043 | .8756 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 0.872 | 0.369-2.058 | .7545 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.942 | 0.446 -1.992 | .8766 | |||

| Not responder to bridging | 3.407 | 1.550-7.487 | .0023 | 3.576 | 1.472-8.686 | .0049 |

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.790 | 0.168-3.725 | .7663 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.438 | 0.625-3.307 | .3925 | |||

| Ki-67 (%) ≥30% | 3.111 | 0.898-10.780 | .0735 | |||

| POD24 | 0.382 | 0.115- 1.262 | .1144 | |||

| Bulky disease | 0.903 | 0.404-2.018 | .8039 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 6.257 | 1.922-20.367 | .0023 | 4.095 | 1.207-13.897 | .0238 |

| ECOG in class at infusion ≥2 | 2.091 | 0.892-4.902 | .0897 | |||

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion > upper limit | 1.470 | 0.680-3.175 | .3274 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 1.598 | 0.730-3.499 | .2408 | |||

| CRS | 1.401 | 0.487-4.030 | .5320 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.458 | 0.701-3.034 | .3134 | |||

| TCE salvage treatment vs others | 0.391 | 0.118-1.299 | .1253 | |||

| Prognostic factors . | Univariate model . | MCL treated patients, N = 49 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate model∗ . | ||||||

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| PFS2 | ||||||

| Age at infusion | 0.990 | 0.958-1.023 | .5557 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 0.657 | 0.306-1.407 | .2792 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.896 | 0.451-1.776 | .7523 | |||

| Nonresponder to bridging | 1.866 | 0.930-3.745 | .0792 | |||

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.467 | 0.125-1.749 | .2587 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.206 | 0.556-2.617 | .6360 | |||

| Bulk disease | 0.818 | 0.401-1.667 | .5802 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 4.025 | 1.307-12.395 | .0152 | 3.268 | 1.036-10.305 | .0433 |

| ECOG PS in class at infusion ≥2 | 1.306 | 0.585-2.912 | .5147 | |||

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion more than the upper limit | 1.015 | 0.499-2.066 | .9666 | |||

| POD24 | 0.442 | 0.156-1.256 | .1255 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 2.186 | 1.074-4.452 | .0311 | 2.199 | 1.010-4.791 | .0472 |

| CRS | 0.625 | 0.258-1.514 | .2979 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.246 | 0.643-2.412 | .5146 | |||

| TCE salvage treatment vs others | 0.598 | 0.210-1.701 | .3351 | |||

| OS2 | ||||||

| Age at infusion | 1.003 | 0.965-1.043 | .8756 | |||

| Number of previous lines >2 | 0.872 | 0.369-2.058 | .7545 | |||

| Number of previous lines >3 | 0.942 | 0.446 -1.992 | .8766 | |||

| Not responder to bridging | 3.407 | 1.550-7.487 | .0023 | 3.576 | 1.472-8.686 | .0049 |

| Ann Arbor stage in class III-IV | 0.790 | 0.168-3.725 | .7663 | |||

| TP53 mutation | 1.438 | 0.625-3.307 | .3925 | |||

| Ki-67 (%) ≥30% | 3.111 | 0.898-10.780 | .0735 | |||

| POD24 | 0.382 | 0.115- 1.262 | .1144 | |||

| Bulky disease | 0.903 | 0.404-2.018 | .8039 | |||

| High MIPI risk at infusion (≥6.2) | 6.257 | 1.922-20.367 | .0023 | 4.095 | 1.207-13.897 | .0238 |

| ECOG in class at infusion ≥2 | 2.091 | 0.892-4.902 | .0897 | |||

| LDH (IU/L) at infusion > upper limit | 1.470 | 0.680-3.175 | .3274 | |||

| Blastoid variant | 1.598 | 0.730-3.499 | .2408 | |||

| CRS | 1.401 | 0.487-4.030 | .5320 | |||

| Neurotoxicity | 1.458 | 0.701-3.034 | .3134 | |||

| TCE salvage treatment vs others | 0.391 | 0.118-1.299 | .1253 | |||

CRS, cytokine release syndrome; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Multivariate analysis was performed on 42/49 for PFS and 44/49 patients with available data for OS.

Discussion

Brexu-cel and, more recently, lisocabtagene maraleucel,6 have emerged as key therapeutic options for the management of R/R MCL. However, RW evidence highlights a significant post–CAR-T relapse rate, with no plateau observed in survival curves. In this study, we analyzed the outcomes of patients in failure after brexu-cel therapy and showed that these patients have extremely poor outcomes, with a median PFS2 of 1.8 months and OS2 of 5.8 months after failure. The wide range of nonstandardized treatments administered after CAR-T failure further underscores the critical unmet therapeutic needs in this population. These data are in line with those reported at the 2024 American Society of Hematology meeting, by Epstein-Peterson et al,14 in North American patients (median PFS2, 2.3 months; median OS2, 5.4 months).

Although the sample size is limited, in our series, CD3-CD20 bispecific antibodies appear to be a promising treatment avenue for patients with R/R MCL with a CR rate of 43%, and no relapse observed after a median FU of 15 months. These results should be interpreted with caution, but mirror the data observed in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in which bispecific antibodies represent 1 of the best salvage options after CAR-T failure.15 In a phase 1/2 trial, Phillips et al16 reported an ORR of 85%, CR rate of 78.3%, and duration of CR of 15.4 months with glofitamab in a cohort of 60 patients with R/R MCL, which, however, included only 2 patients (3.3%) treated after CAR-T therapy failure. Of note, the pivotal phase 3 GLOBRYTE study17 is currently recruiting patients, in the post-BTKi and pre-CAR-T setting. Similarly, Wang et al18 described on an expansion cohort of R/R MCL from a phase 1/2 trial investigating mosunetuzumab in combination with polatuzumab vedotin, ORR/CR rates of 75%/70% among 20 patients, including 7 (35%) who had previously received CAR-T therapy.

Importantly, in our cohort, post–brexu-cel failure salvage therapy based on covalent BTKis, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitors, or another targeted agent showed no efficacy. None of the patients included in our study received a noncovalent BTKi such as pirtobrutinib, which could represent a potential option and therefore a limitation in our study. Indeed, the pivotal phase 2 BRUIN trial19 showed 38% of responders after CAR-T therapy among 13 patients treated. For patients with a localized disease, radiation could be an option to consider, with a favorable safety profile in a context in which cytopenia and other post–CAR-T complications might preclude from other treatment. Other routinely available options such as Len/R2 or ICT showed a low ORR, highlighting again the need to include patients in clinical trials, whenever possible, because available strategies do not seem to provide a satisfying answer. Within the clinical characteristics, the presence of a blastoid variant, MIPI score, and ECOG PS at time of CAR-T infusion were among the most important prognostic factors, alongside with the previous response to bridging therapy and independently of the treatment received at time of CAR-T failure. This highlights the consistency of baseline high-risk features (namely MIPI score, or pathological variant) during disease evolution, and their relevance for the later line of treatment. The strength of the predictive value of response to bridging therapy on survival, both in the global,8 and in the R/R post–CAR-T population presented here, should prompt reflection on whether or not to proceed with CAR-T infusion in the context of postbridging progression. However, this requires further analysis in larger cohorts.

Our study has several limitations, including missing data, such as for TP53 mutation status or the morphological evaluation (presence of a blastoid variant). The absence of clinical data at time of CAR-T failure, including key markers such as Ki-67 or TP53 mutational status that may evolve over time, can represent another issue here, although the prognosis analysis showed consistency with known high-risk feature.20 Finally, the low numbers and heterogeneity of treatment received preclude from extrapolation and requires validation in other cohorts, although in the US cohort data, bispecific also showed efficacy14 (ORR 60%). Furthermore, therapy selection after relapse may be influenced by clinical characteristics, for instance, the use of local radiotherapy in patients with unifocal disease, as well as inclusion in clinical trials for TCEs. Importantly, despite these limitations, given the observed PFS2 and OS2, the main message of the manuscript, that is, the poor outcome and unmet medical need, is not altered.

To conclude, patients with MCL in the DESCAR-T registry who experienced failure after brexu-cel injection had very poor outcomes, with no standardized treatment currently available for this challenging population. Despite the small sample size, our findings suggest that TCEs may provide durable responses whereas no benefit seems to be observed with targeted therapies such as BTKis/anti–B-cell lymphoma 2. Given the small sample size, these data need to be confirmed by larger and confirmatory cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families, as well as the entire DESCAR-T team, the coinvestigators, and the participating centers that made this study possible. The authors also extend their gratitude to the entire LYSARC group, particularly the statisticians who contributed to the project, as well as the cooperative groups (Lymphoma study association [LYSA], Intergoupe francophone du myélome [IFM], Société française de lutte contre les cancers et leucémies de l'enfant et de l'adolescent [SFCE], Société francophone de greffe de moelle et de thérapie cellulaire [SFGM-TC], Group for research in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemias [GRAALL]) and our partners (Gilead/Kite, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb).

Authorship

Contribution: M.A., M.C., and C.S. conceived the study, designed the methodology, and wrote the manuscript; A.C. and E.G. performed the statistical analyses; and all authors contributed to, provided, and reviewed the data and the manuscript, and treated patients included in the DESCAR-T registry.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.H. received honoraria from Novartis, Incyte, Janssen, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD), Takeda, Roche, and AbbVie; received honoraria and served on the board of directors or advisory committees for Kite/Gilead; and provided consultancy for Kite/Gilead, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS)/Celgene, Incyte, Miltenyi, Roche, and AbbVie. C.T. provided consultancy for Novartis, Janssen, BeiGene, AbbVie, Takeda, Kite/Gilead, Regeneron, and BMS/Celgene; received honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Incyte, Sanofi, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, Bayer, Takeda, and Regeneron; and received research funding from AbbVie and Roche. L.Y. held membership on the board of directors or advisory committees of, and received research funding from, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche, BeiGene, BMS/Celgene, and Gilead/Kite. O.H. received research funding from MSD Avenir, BMS, Alexion, and Roche; and provided consultancy for, held equity ownership in a publicly traded company, held patents and received royalties from, and received research funding from, Inatherys and AB Science. B.T. received honoraria from Lilly and Novartis; and reports travel accommodations from Gilead and AbbVie. C.H. provided consultancy for, and received honoraria, travel support, and research funding from, Kite/Gilead, Janssen, and AbbVie; and provided consultancy for, and received honoraria from, Roche/Genentech, BMS, and Takeda. C.S. provided consultancy for Prelude and BeiGene; received honoraria from BeiGene and AstraZeneca; and received research funding from Roche. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

A complete list of the members of the LYSA Group appears in “Appendix.”

Correspondence: Clémentine Sarkozy, Hematology Department, Institut Curie, 35 rue Dailly, 92110 Saint-Cloud, France; email: clementine.sarkozy@curie.fr.

References

Author notes

Data can be shared for academic collaboration on request to LYSARC via the corresponding author, Clémentine Sarkozy (clementine.sarkozy@curie.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.