Key Points

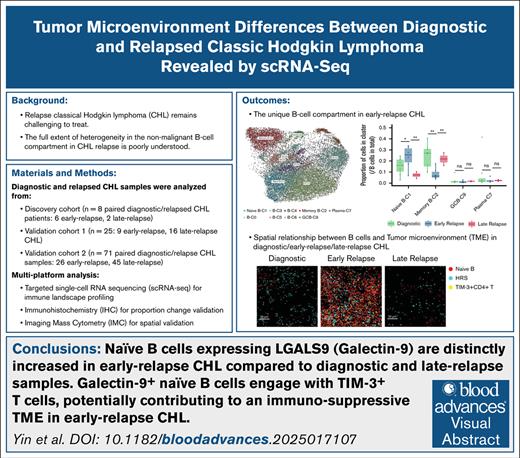

Naïve B cells expressing LGALS9 (galectin-9) are distinctly increased in early-relapse CHL compared to diagnostic and late-relapse samples.

Galectin-9–positive naïve B cells engage with TIM-3+ T cells, potentially contributing to an immunosuppressive TME in early-relapse CHL.

Visual Abstract

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) is characterized by a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) that supports disease progression. Although immune cell recruitment by Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells is well documented, the role of nonmalignant B cells in relapse remains unclear. Using single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on paired diagnostic and relapsed CHL samples, we identified distinct shifts in B-cell populations, particularly an enrichment of naïve B cells and a reduction of memory B cells in early-relapse CHL compared to late-relapse and newly diagnosed CHL. The enrichment of naïve B cells in early relapse biopsies was confirmed in independent validation cohorts using scRNA-seq and immunohistochemistry. Notably, naïve B cells in early-relapse samples exhibited high expression of LGALS9, an immunosuppressive gene encoding galectin-9, which binds to HAVCR2 (T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing protein 3 [TIM-3]) on regulatory T cells (Tregs). Cell-cell interaction analysis revealed the importance of interactions between LGALS9+ naïve B cells and HAVCR2+ Tregs in the early-relapse setting. Spatial analysis by imaging mass cytometry confirmed close proximity of galectin-9–positive naïve B cells with TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells and HRS cells, pointing to their role in shaping an immunosuppressive niche. Our findings highlight a previously unrecognized population of galectin-9–positive naïve B cells with immunoregulatory potential in early-relapse CHL and provide new insights into the spatial and transcriptional architecture of the relapsed TME in CHL.

Introduction

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) is a type of lymphoma that is characterized by the presence of malignant Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells, which represent ∼1% of cells in biopsy tissues.1 Current pathogenesis models suggest that HRS cells recruit immune cells to the tumor microenvironment (TME) to form a well-organized tumor-supporting niche.2 Although the introduction of novel agents such as brentuximab vedotin and immune checkpoint inhibitors has improved first-line treatment outcomes in CHL,3-5 a subset of patients still experience relapse, which continues to pose a major therapeutic challenge.6 In particular, early relapse is associated with inferior clinical outcomes,7 yet the underlying biology remains elusive.

Recent research has increasingly focused on the role of the TME in CHL pathogenesis, revealing complex cellular interactions that contribute to immune evasion, treatment resistance, and relapse. Most studies have investigated the prognostic significance of immune cell infiltration in the CHL microenvironment, particularly T cells and macrophages, often incorporating phenotypic subclassification.8-11 In contrast, the role of nonmalignant B cells within the CHL TME remains relatively underexplored. Although several studies have associated the presence of B cells, assessed by canonical markers such as CD20 and B-cell–related gene signatures, with favorable prognosis,11-15 these analyses have not explored heterogeneity within the B-cell compartment. Moreover, detailed analyses of B cells in relation to early vs late relapse are lacking.

In our previous work, we compared diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL samples using imaging mass cytometry (IMC) to spatially map immune populations in the TME. We found that the proportion of B cells were reduced in early-relapse samples, whereas their presence, particularly CXCR5+ B cells in proximity to HRS cells, was associated with favorable outcomes.16 However, this analysis was limited by the number of simultaneously assessable markers, preventing detailed phenotypic classification of B-cell subsets, such as naïve and memory B-cell populations, and limiting the ability to infer their potential roles within the TME.

To address this gap, we used targeted single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to comprehensively profile paired diagnostic and relapsed CHL samples, with a focus on the nonmalignant B-cell compartment. Our analysis revealed a previously unrecognized enrichment of naïve B cells expressing galectin-9 and interactions with T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain–containing protein 3–positive (TIM-3+) T cells in early-relapse CHL, suggesting a role for the galectin-9–TIM-3 axis in fostering an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Methods

Cohort information

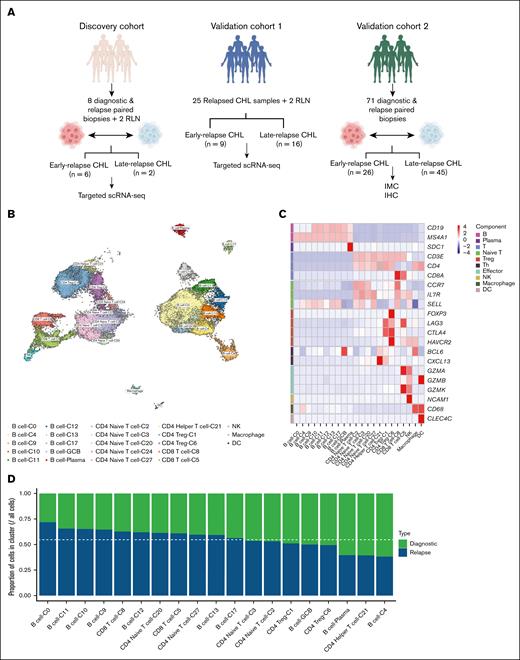

Paired diagnostic and relapse lymph node biopsies from a total of 8 patients with histologically confirmed CHL were selected based on the availability of fresh-frozen cell suspensions. Samples were collected as part of routine clinical care at BC Cancer, Vancouver. Two reactive lymph node (RLN) samples diagnosed as lymphoid hyperplasia (but no evidence of malignant disease or systemic autoimmune condition) were included as controls (discovery cohort; Figure 1A). Patients were classified as early relapse (n = 6) if disease progressed within 12 months after initial diagnosis or if their disease was refractory to first-line ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine)-like treatment. Those with later disease progression were classified as late relapse (n = 2). Detailed patient characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

scRNA-seq profiling in diagnostic and relapsed CHL. (A) Study cohort composition; overview of the discovery cohort used for targeted hybrid-capture sequencing; validation cohort 1 (targeted hybrid-capture sequencing); and validation cohort 2 (IHC and IMC). (B) UMAP visualization of all major immune cell populations across CHL and RLN samples in the discovery cohort. (C) Heat map showing the canonical marker expression in each cell cluster. (D) Proportional changes in B- and T-cell clusters between diagnostic and relapsed CHL samples in the discovery cohort. The white dashed line represents the expected ratio of cell proportions from relapse samples based on the total cell number of diagnostic and relapse samples. GCB, germinal center B cell; NK, natural killer cell; Th, T helper cell; Treg, regulatory T cell.

scRNA-seq profiling in diagnostic and relapsed CHL. (A) Study cohort composition; overview of the discovery cohort used for targeted hybrid-capture sequencing; validation cohort 1 (targeted hybrid-capture sequencing); and validation cohort 2 (IHC and IMC). (B) UMAP visualization of all major immune cell populations across CHL and RLN samples in the discovery cohort. (C) Heat map showing the canonical marker expression in each cell cluster. (D) Proportional changes in B- and T-cell clusters between diagnostic and relapsed CHL samples in the discovery cohort. The white dashed line represents the expected ratio of cell proportions from relapse samples based on the total cell number of diagnostic and relapse samples. GCB, germinal center B cell; NK, natural killer cell; Th, T helper cell; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Two independent validation cohorts were included (Figure 1A). Validation cohort 1 comprised relapse-only samples from 25 additional patients with CHL, including 9 with early relapse and 16 with late relapse, which were analyzed by scRNA-seq. Detailed patient characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table 2. Validation cohort 2 consisted of a tissue microarray containing paired diagnostic and relapse formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies from 71 patients with CHL, previously described in Aoki et al.16 This cohort was used for validation by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and IMC. All study protocols were approved by institutional research ethics boards, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

10x Chromium scRNA-seq and library preparation

Lymph node cell suspensions were thawed rapidly at 37°C and washed in either a solution of RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum or RPMI-1640 with 20% fetal bovine serum solution containing DNase I (MilliporeSigma). Sorting of viable cells (DAPI [4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole] negative) was performed using either a fluorescence-activated cell sorter AriaIII or fluorescence-activated cell sorter Fusion (BD Biosciences) with an 85-μm nozzle. The sorted cells were collected in 0.5 mL of medium, centrifuged, and diluted in 1× phosphate-buffered saline with 0.04% bovine serum albumin. Cells were then loaded into a Chromium Single-Cell 5’ Chip Kit v2 (PN-120236) and processed according to the instructions provided in the Chromium Single-Cell 5’ Reagent Kit v2 user guide. Construction of libraries was performed using the Single 5’ Library and Gel Bead Kit v2 (PN-120237) and Chromium i7 Multiplex Kit v2 (PN-120236). The captured library was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity chip and Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit, and sequencing was performed on an Illumina Nextseq550. To boost transcriptome information, hybridization capture17 of 177 marker genes (supplemental Table 3) was performed as described previously using Twist Hybridization and Wash kit (Twist Bioscience). The captured library was measured using Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity chip and Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit and was run on Illumina Nextseq550.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Analysis and visualization of scRNA-seq data from the discovery cohort and validation cohort 1 were performed in the R statistical environment (version 4.1.0). Cell Ranger software (version 6.0.2) was used to align sequencing reads to the hg38 human reference genome build. CellRanger (v6.0.2) count data from all cells were read into a single “Seurat” object using the Seurat package (version 4.2.1).18 Cells were filtered if they had ≥20% reads aligning to mitochondrial genes or if they were ≥3 median absolute deviations from the median. The read count matrix was used as input into the “NormalizeData” function, which returned the normalized expression matrix. Normalized log counts for genes with biological variance ≥0 were used as input into the scanorama R package (version 1.6) to perform batch correction.19 Principal component analysis (PCA) was then run on the batch-corrected expression matrix using highly variable genes identified by the “FindVariableGenes” function. Unsupervised clustering was performed with the “FindClusters” function, using the first 30 PCA components as input. Clusters were manually assigned to a cell type by comparing the mean expression of known markers across cells in a cluster. Markers used to annotate cells included CD19, CD20 (B cells), CD3, CD4, CD8 (T cells), CD68 (macrophages), and CD303 and CD304 (dendritic cells [DCs]). The clustering results were shown in the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) space, which was generated using the first 30 PCA components.

We next conducted a differential expression analysis between B cells obtained from diagnostic samples and those from relapse samples. This analysis was performed using the “FindMarkers” function in the Seurat package. A log-scaled fold change threshold of 1.0 and an adjusted P value threshold of <.05 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) were used to determine the significance of differential expression.

The CellChat R package (version 1.1.3) was used to identify potential cell-cell communication networks from scRNA-seq data.20 Cells were classified into broad subtypes based on their cluster assignments, which were input into CellChat as cell labels. The ligand-receptor interaction database (n = 1999) used for predicting intercellular communications was the CellChat built-in cross-referencing ligand-receptor interaction database (n = 1939) and a manually curated list of ligand-receptor interactions (n = 60) in the CHL TME. The communication probability was calculated for each ligand-receptor pair, identifying significant interactions based on adjusted P values <.05.

IHC

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections were stained for immunoglobulin D (IgD) to identify naïve B cells. After deparaffinization and citrate-based antigen retrieval, sections were incubated with an anti-human IgD antibody (clone IA6-2; BD Biosciences; 1:100) for 1 hour at room temperature. Detection was performed using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen system, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. IgD+ B cells were quantified within CD20+ B-cell areas using brightfield microscopy.

Spatial analysis using IMC

IMC was conducted on samples from validation cohort 2, using cell segmentation and 2-step annotation previously established and described in our published study.16 Naïve B cells were defined based on coexpression of CD20, CXCR5, and galectin-9, consistent with transcriptional signatures identified in the scRNA-seq analysis. Spatial proximity was assessed using a custom published pipeline16 to calculate a spatial interaction score, defined as the average distance from each naïve B cell to its 5 nearest neighboring cells of interest within a maximum interaction radius of 50 μm. This per-cell metric normalizes for differences in cell abundance across samples.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.1). For paired comparisons, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. For unpaired comparisons, the Mann-Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) was applied. Statistical significance was defined as P value <.05.

Results

scRNA-seq profiling of the cellular ecosystem in diagnostic and relapsed CHL

We first analyzed 8 paired diagnostic and relapse CHL samples (early relapse, n = 6; late relapse, n = 2), representing a subset of cases described in our previous work,16 and included 2 RLN samples as controls (discovery cohort; Figure 1A). After quality filtering, the merged scRNA-seq data set comprised 49 843 high-quality single-cell transcriptomes (average, 2770 cells per sample; range, 458-5331). Unsupervised clustering followed by UMAP dimensionality reduction revealed distinct clusters corresponding to major immune cell lineages, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, B cells, macrophages, and DCs (Figure 1B-C). Of note, our technology and analysis pipeline could not detect malignant HRS cells, and the proportions of myeloid populations were lower than in the same cases previously analyzed by IMC16 (macrophages, 0.6% vs 8.3%; DCs, 0.07% vs 5.6%), likely due to depletion during cell preparation and microfluidic procedures, consistent with our earlier report.21

Given the low representation of macrophages and DCs in our data set, we focused on B and T cells and examined the distribution of transcriptionally defined clusters between diagnostic and relapsed samples. Among B cells, cluster composition varied notably between diagnostic and relapsed samples, whereas relative abundance of T-cell clusters remained largely stable across biopsy time points (Figure 1D). These findings prompted us to focus our downstream analyses on the B-cell compartment, which appeared particularly dynamic between disease phases.

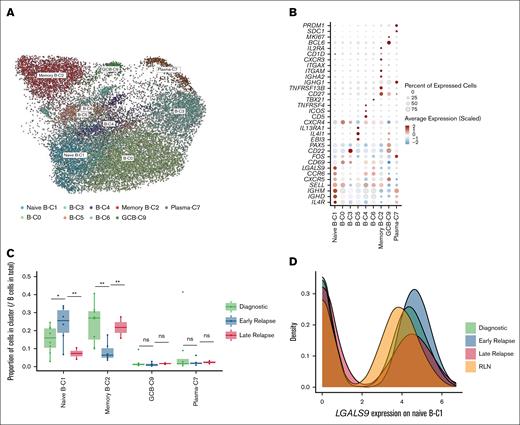

The unique B-cell compartment in early-relapse CHL

To gain further insight into the dynamic shift in the B-cell compartment, we performed detailed transcriptional profiling of subsets to delineate their phenotypic composition and potential associations with biopsy time points. Unsupervised clustering of the B-cell subset revealed 9 transcriptionally distinct clusters, each representing a unique transcriptional profile suggestive of different differentiation or activation states (Figure 2A). These clusters were annotated based on canonical marker expression and included naïve B cells (C1), memory B cells (C2), germinal center B cells (C9), and plasma cells (C7). The remaining 5 clusters did not correspond to well-defined phenotypes but displayed distinct transcriptional profiles suggestive of functional or developmental heterogeneity (Figure 2B). The naïve B-cell cluster (naïve-B-C1) was characterized by strong expression of IGHD, IGHM, IL4R, and SELL, as well as homing receptors such as CXCR5 and CCR6, consistent with a phenotype of antigen-inexperienced, follicular-homing B cells. In contrast, memory B cells (C2) expressed CD27, TNFRSF13B (TACI), CXCR3, and ITGAM (CD11b), reflecting a class-switched, antigen-experienced population.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals distinct B-cell populations in diagnostic and relapsed CHL. (A) UMAP visualization of B-cell subclusters in the discovery cohort. (B) Dot plot showing the top differentially expressed genes in each B-cell subclusters. The bubble size shows the percentage of cells with gene expression, and the color shows the scaled expression (by rows). (C) Proportional analysis of B-cell subclusters across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL samples in the discovery cohort. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (D) LGALS9 expression in naïve B cells across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL, demonstrating significant upregulation in early-relapse samples in the discovery cohort. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. GCB, germinal center B cell; ns, not significant.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals distinct B-cell populations in diagnostic and relapsed CHL. (A) UMAP visualization of B-cell subclusters in the discovery cohort. (B) Dot plot showing the top differentially expressed genes in each B-cell subclusters. The bubble size shows the percentage of cells with gene expression, and the color shows the scaled expression (by rows). (C) Proportional analysis of B-cell subclusters across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL samples in the discovery cohort. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (D) LGALS9 expression in naïve B cells across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL, demonstrating significant upregulation in early-relapse samples in the discovery cohort. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. GCB, germinal center B cell; ns, not significant.

Consistent with our previous IMC-based findings,16 the overall proportion of B cells tended to be lower in early-relapse samples than diagnostic and late-relapse samples (supplemental Figure 1A), although this difference did not reach statistical significance, likely due to limited sample size. Interestingly, the naïve-B-C1 was significantly enriched (P < .05) in early-relapse samples compared to both diagnostic and late-relapse samples (Figure 2C). Conversely, the memory B-cell cluster C2 displayed an opposite enrichment, with a statistically significant decrease of cells from early-relapse samples compared to both diagnostic and late-relapse samples (P < .05; Figure 2C).

To identify transcriptional features specific to early-relapse CHL, we performed a global differential expression analysis comparing naïve-B-C1 from early-relapse samples to those from diagnostic, late-relapse, and RLN controls. This analysis revealed a set of significantly upregulated genes in early-relapse CHL, including LGALS9, HLA-DRB5, IGHM, SPIB, SELL, and CD79A (supplemental Figure 1B; Figure 2D). Among these, we focused on LGALS9, which encodes galectin-9, a protein described to exert immunosuppressive effects within the TME by inducing apoptosis primarily in T cells, through interactions with TIM-3.22 Its high expression specifically in naïve-B-C1 from early-relapse CHL suggests a potential contribution to the establishment of an immunosuppressive niche that may facilitate early relapse.

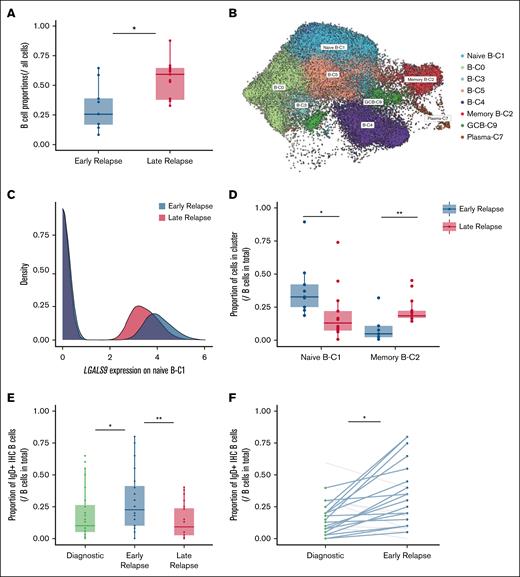

Validation of naïve B-cell enrichment in early-relapse CHL across independent cohorts

To validate our findings regarding the unique B-cell compartments in early-relapse CHL, we performed scRNA-seq on an independent cohort of 9 patients with early-relapse CHL and 16 with late-relapse CHL (validation cohort 1). In line with the trend observed in the discovery cohort, the overall proportion of B cells was significantly lower in early-relapse samples than late-relapse samples (P < .05; Figure 3A). We then performed B-cell subclustering and annotated cell types using label transfer from the discovery cohort, which served as the reference data set, yielding 1 naïve-B-C1, 1 memory B-cell cluster, 1 germinal center B-cell cluster, 1 plasma cluster, and 4 unclassified clusters (Figure 3B). Consistent with the results from the discovery cohort, early-relapse CHL showed higher expression of LGALS9 (P < .05; Figure 3C) and was significantly enriched in naïve B cells (P < .05; Figure 3D), whereas late-relapse CHL showed enrichment of memory B cells (P < .05; Figure 3D). Additionally, to confirm the increased presence of unswitched naïve B cells in early-relapse samples on the protein level in an extension cohort (n = 71; validation cohort 2), we used IgD IHC and found a statistically significant enrichment of naïve B cells in early-relapse samples compared to both diagnostic (P < .05; Figure 3E-F) and late-relapse samples (P < .05; Figure 3E).

Validation of naïve B-cell enrichment and LGALS9 expression in independent CHL cohorts. (A) Proportional analysis of total B-cell populations in early-relapse vs late-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 1. (B) UMAP plot of B-cell subclusters identified in the validation cohort 1. (C) LGALS9 expression in naïve B cells in the validation cohort 1. (D) Proportional analysis of naïve and memory B-cell populations in early-relapse vs late-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 1. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (E) Quantification of IgD+ B cells across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL samples based on IHC staining of validation cohort 2. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (F) Paired statistical analysis (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) comparing IgD+ naïve B-cell proportions between diagnostic and early-relapse CHL samples based on IHC staining of validation cohort 2. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. GCB, germinal center B cell.

Validation of naïve B-cell enrichment and LGALS9 expression in independent CHL cohorts. (A) Proportional analysis of total B-cell populations in early-relapse vs late-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 1. (B) UMAP plot of B-cell subclusters identified in the validation cohort 1. (C) LGALS9 expression in naïve B cells in the validation cohort 1. (D) Proportional analysis of naïve and memory B-cell populations in early-relapse vs late-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 1. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (E) Quantification of IgD+ B cells across diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL samples based on IHC staining of validation cohort 2. Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. (F) Paired statistical analysis (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) comparing IgD+ naïve B-cell proportions between diagnostic and early-relapse CHL samples based on IHC staining of validation cohort 2. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. GCB, germinal center B cell.

Cellular cross talk between B cells and TME in early-relapse CHL

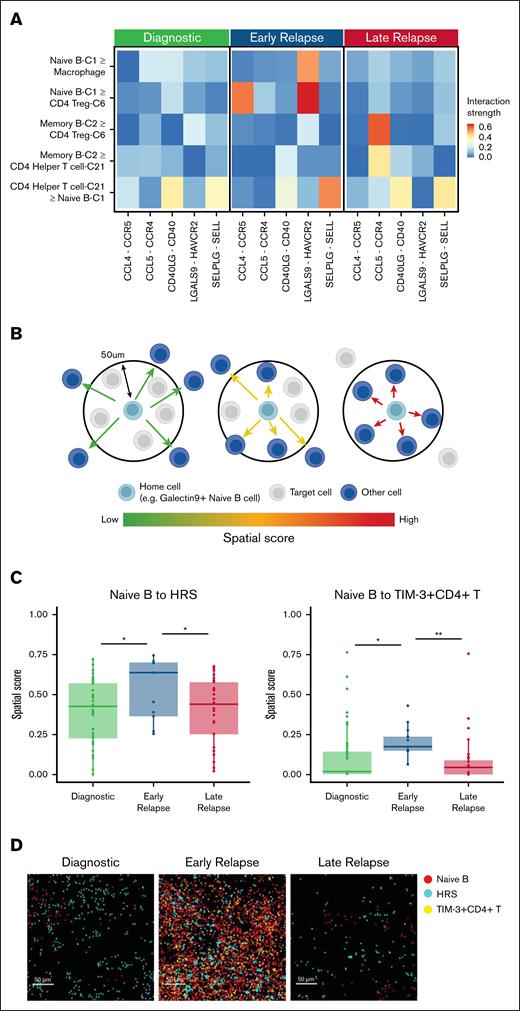

To further investigate the B-cell–related cellular interactions within the TME across different disease states, we performed cell-cell interaction analysis using CellChat12 on scRNA-seq data from the discovery cohort. The analysis was performed on diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL separately and revealed that cells in the naïve B-C1 were predicted to interact uniquely with regulatory T cells and macrophages in early-relapse samples via the LGALS9-HAVCR2 (galectin-9–TIM-3) axis, in which LGALS9 was expressed on naïve-B-C1 cells and HAVCR2 on regulatory T cells (P < .05; Figure 4A).

Cell-cell interactions between naïve B cells and Tregs in early-relapse CHL. (A) Cell-cell interaction analysis using CellChat, highlighting significant interactions between LGALS9+ naïve B cells and Tregs via the LGALS9-HAVCR2 axis in early-relapse CHL in the discovery cohort. (B) Schematic representation of spatial analysis of naïve B cells in the TME. (C) Spatial score analysis demonstrating increased proximity of naïve B cells to HRS cells in early-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 2. A t test was used for statistical analysis. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. (D) Spatial distribution of naïve B cells, HRS cells, and TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells in diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL, supporting their increased interactions in early-relapse cases in the validation cohort 2. Treg, regulatory T cell.

Cell-cell interactions between naïve B cells and Tregs in early-relapse CHL. (A) Cell-cell interaction analysis using CellChat, highlighting significant interactions between LGALS9+ naïve B cells and Tregs via the LGALS9-HAVCR2 axis in early-relapse CHL in the discovery cohort. (B) Schematic representation of spatial analysis of naïve B cells in the TME. (C) Spatial score analysis demonstrating increased proximity of naïve B cells to HRS cells in early-relapse CHL in the validation cohort 2. A t test was used for statistical analysis. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01. (D) Spatial distribution of naïve B cells, HRS cells, and TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells in diagnostic, early-relapse, and late-relapse CHL, supporting their increased interactions in early-relapse cases in the validation cohort 2. Treg, regulatory T cell.

To validate the cell-cell interaction results from scRNA-seq at the protein level and gain a more comprehensive understanding of spatial relationships between nonmalignant B cells and other cell types, we analyzed published IMC data focusing on B-cell subsets (validation cohort 2).6 We defined naïve B cells as CD20+, CXCR5+, and galectin-9 positive to align with the coexpression patterns observed in the scRNA-seq data for naïve-B-C1 (Figure 2B). IMC, unlike conventional IHC, provides quantitative and continuous measurements of protein expression at single-cell resolution, allowing us to assess galectin-9 expression with high precision. Consistent with the scRNA-seq findings, galectin-9 protein expression levels were significantly elevated on naïve B cells in early-relapse samples compared to both diagnostic and late-relapse samples (supplemental Figure 2A).

To quantify spatial organization, we calculated a spatial score as previously described,6 defined as the average distance from each naïve B cell to its 5 nearest neighboring target cells, within a maximum radius of 50 μm (Figure 4B). This per-cell metric allows for normalization of variation in cell density and enables robust comparisons across samples. Our analysis revealed that naïve B cells were significantly closer to HRS cells in early-relapse samples than in diagnostic and late-relapse samples (P < .05; Figure 4C-D). Similarly, naïve B cells exhibited reduced distances to TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells in early-relapse samples (P < .05; Figure 4C-D). Interestingly, a majority proportion of TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells also coexpressed V-domain immunoglobulin-containing suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA; supplemental Figure 2B), which has also been reported to bind galectin-9.23 This interaction, together with the known role of VISTA as a negative immune checkpoint regulator,24 suggests that galectin-9 exert immunosuppressive effects through both TIM-3 and VISTA pathways in early-relapse CHL.

Discussion

Our study uncovered distinct differences in the nonmalignant B-cell compartments between diagnostic and relapse CHL, particularly in early-relapse CHL. Consistent with our previous IMC-based findings, the overall proportion of B cells tended to be lower in early-relapse samples than in both diagnostic and late-relapse samples. Although this trend did not reach statistical significance in the discovery cohort, it was confirmed with statistical significance in the independent validation cohort 1 including only relapse samples. Importantly, despite a reduction in the overall B-cell population, single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed a compositional shift within the B-cell compartment and enrichment of naïve B cells in early-relapse CHL. This key finding was further confirmed by IgD IHC on a previously reported cohort16 of 71 CHL cases (validation cohort 2), which demonstrated a significant enrichment of naïve B cells in early-relapse CHL.

Our results further revealed that LGALS9 (galectin-9) expression at both messenger RNA (scRNA-seq) and protein (IMC) levels was significantly elevated in naïve B cells from early-relapse CHL samples compared to those from diagnostic, late-relapse, and RLN tissues. Galectin-9, known for its immunosuppressive properties, may modulate the activity of other immune cells through the galectin-9–TIM-3 axis. This hypothesis was supported by our spatial analysis, which revealed that galectin-9–positive naïve B cells were located in close proximity not only to HRS cells but also to TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells. This axis, observed in interactions between galectin-9–positive naïve B cells and TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells, highlights a potential mechanism for immune evasion in early-relapse CHL that might be additive to other well-described mechanisms of immune escape in CHL, such as HRS cell loss of immunogenicity, overexpression of PDL1/PDL2, and recruitment of immunomodulatory T-cell subsets.1

Conversely, memory B cells were significantly reduced in early-relapse CHL relative to diagnostic and late-relapse time points. Previous studies have shown that galectin-9 is autologously produced by naïve B cells and binds CD45, suppressing calcium signaling via a mechanism dependent on Lyn, CD22, and SHP-1 that blunts B-cell activation.25,26 Given that galectin-9 expression was markedly elevated in naïve B cells from early-relapse CHL, the reduction of memory B cells in these samples might indicate that galectin-9–positive naïve B cells are lacking capacity to transition to more functionally active B-cell states, thus contributing to a less effective B-cell–mediated immune response.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, although our data revealed the depletion of memory B cells in early-relapse CHL, it remains unclear whether these changes are restricted to the TME or reflect systemic immune dysregulation, particularly given the lack of matched peripheral blood or bone marrow samples to assess systemic immune status. Reduced memory B-cell abundance may be a consequence of prior chemotherapy or indicative of impaired immune reconstitution. Second, although we observed galectin-9 enrichment in naïve B cells and their spatial proximity to TIM-3+ CD4+ T cells and HRS cells, the underlying mechanism remains unclear, including whether galectin-9–positive naïve B cells contribute to TIM-3+ T-cell induction and why galectin-9 expression is elevated in early-relapse CHL. Third, our study has a low number of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–positive CHL cases, limiting our ability to assess the impact of viral status on B-cell composition. Because EBV+ CHL exhibits distinct immunologic features, EBV-stratified studies will be needed to determine whether the enrichment of galectin-9–positive naïve B cells is specific to EBV– disease.

In summary, our results highlight an underexplored role of B cells in CHL and uncover distinct transcriptional and spatial features of galectin-9–positive naïve B cells. These findings underscore the need for further studies to elucidate the functional significance of B-cell–mediated immune regulation in CHL, particularly in early-relapse disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Terry Fox Research Institute Program Project grants (1061 and 1108), the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group, and a Large Scale Applied Research Project funded by Genome Canada (13124), Genome BC (271LYM), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; GP1-155873), the British Columbia Cancer Foundation, and the Provincial Health Services Authority. T.A. was supported by a fellowship from the Japanese Society for The Promotion of Science and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. T.A. was supported by a fellowship from CIHR, the Lymphoma Research Foundation, and the Uehara Memorial Foundation. T.A. received research funding support from The Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science. T.A. is the recipient of a Lymphoma Research Foundation Lymphoma Scientific Research Mentoring Program Scholarship award.

Authorship

Contribution: T.A., D.W.S., K.J.S., and C.S. designed research; T.A., S.R., L.O., and A.T. performed research; A.X., A.M., J.D., and K.J.S. provided materials and data; Y.Y., A.J., L.C., and S.H. analyzed data; Y.Y., T.A., S.R., and C.S. wrote the manuscript; and all authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.W.S. reports consultancy for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Genmab, Roche, and Veracyte; research funding from Roche/Genentech; and is an inventor on patents describing the use of gene expression profiling for subtyping aggressive B-cell lymphomas. K.J.S. reports honoraria/consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Roche, Seagen, and AbbVie; research support from BMS; steering committee participation for Corvus; and data and safety monitoring committee participation for from Regeneron. C.S. is a consultant for Bayer and Eisai; and reports receiving research funding from Epizyme and Trillium Therapeutics Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Christian Steidl, Centre for Lymphoid Cancer, British Columbia Cancer, 675 West 10th Ave, Room 12-110, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1L3, Canada; email: CSteidl@bccancer.bc.ca.

References

Author notes

Y.Y. and S.R. contributed equally to this study.

T.A. and C.S. are joint senior authors.

Presented orally at the 66th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024 (doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2024-209760).

Single-cell RNA sequencing counts (generated with Cell Ranger version 6.0.2) were deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive via controlled access (accession number EGAS00001008222). Imaging mass cytometry data are available at zenodo.org/records/7963681.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.