Key Points

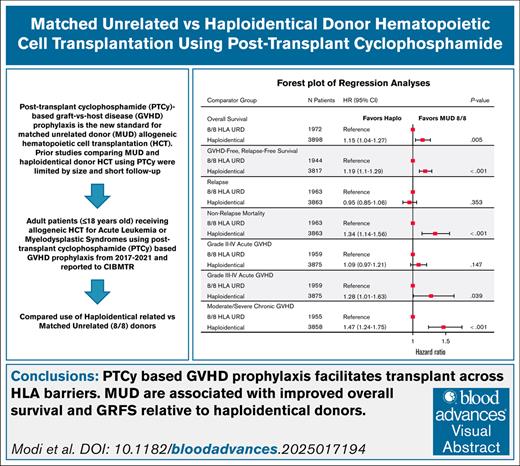

PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis facilitates transplant across human leukocyte antigen barriers.

MUDs are associated with improved OS and GRFS relative to haploidentical donors after HCT using PTCy.

Visual Abstract

Posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy)-based graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis is now standard for matched unrelated donor (MUD) hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Previous studies comparing MUD and haploidentical donor HCT using PTCy were limited in size and follow-up. We therefore performed a registry-based analysis examining the impact of donor type on HCT with PTCy. Adult patients (n = 5873) receiving MUD (n = 1973) or haploidentical (n = 3900) HCT with PTCy for acute leukemia (74.2%) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS; 25.8%) reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research between 2017 and 2021 were included. Primary end points were 3-year overall survival (OS) and GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS). Cox regression and sensitivity analyses were performed through adjustment of propensity scores. Haploidentical HCT had worse OS (hazard ratio [HR], 1.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04-1.27; P = .005) and GRFS (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10-1.29; P < .001) versus MUD HCT. Donor age was the only other donor factor associated with survival. Results were confirmed in sensitivity analysis. When restricted to reduced intensity conditioning or donors <30 years, OS did not differ between groups. Haploidentical HCT was associated with higher primary graft failure (HR, 1.67; P = .002), increased grade 3/4 acute GVHD (HR, 1.28; P = .039), higher moderate/severe chronic GVHD (HR, 1.47; P < .001), and nonrelapse mortality (HR, 1.34; P < .001). Grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD and relapse risk did not differ. This large analysis showed that in adults with acute leukemia or MDS, MUD HCT was associated with improved outcomes versus haploidentical HCT with PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is a curative therapeutic modality for acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Patients have a 13% to 51% chance of having an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched related donor (MRD).1 Patients without an eligible MRD depend on alternative donor sources including, unrelated donors, haploidentical related (haplo) donors, or umbilical cord blood. Recipient ancestry informs the likelihood of identifying a matched unrelated donor (MUD), with the highest probability of finding 8/8 HLA-MUD for non-Hispanic Whites (NHW) patients at 80%, and the lowest probability for Black/African American patients at 29%.2

Posttransplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) has transformed the landscape of haplo-HCT.3-5 PTCy is protective against development of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) due to the depletion of rapidly proliferating alloreactive T cells while preserving hematopoietic progenitor cells and memory and regulatory T cells. Beyond haplo-HCT, the use of PTCy demonstrated encouraging results in HLA-matched related and unrelated donor and mismatched unrelated donor (MMUD) HCT.6-9 Recently, the phase 3 Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network 1703 trial randomized adult patients undergoing MRD or ≥7/8 MMUD HCT using reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) to PTCy/tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or standard GVHD prophylaxis (tacrolimus/methotrexate [MTX]), and reported significantly increased 1-year GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS) and decreased rates of grade 3/4 acute and chronic GVHD with PTCy, tacrolimus, and MMF, establishing PTCy as the standard of care in RIC allogeneic HCT with HLA-matched donors.10

A major, unanswered question remains whether outcomes differ between haplo donors and MUDs when using PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis. A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) study comparing MUD HCT and haplo-HCT with PTCy reported superior overall survival (OS) after MUD HCT using RIC, whereas OS was not different using myeloablative conditioning (MAC).11 The limitations of this study included a relatively small cohort of MUDs (n = 284), short follow-up (RIC cohort was 2 years and MAC cohort was 1 year), and notable differences in the baseline characteristics, particularly donor age, a significant predictor of outcomes in HCT.12 A subsequent reanalysis reported no significant difference between donor types when donor age was added as a variable and the differences between the groups were controlled for by using propensity-score-matched analysis and inverse probability of treatment weighting models.13 Therefore, this study was performed using updated CIBMTR data with a larger sample size to compare longer-term outcomes between MUD HCT and haplo-HCT using PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis.

Methods

Patient eligibility and inclusion

Patient demographics, disease, donor, transplant, and clinical outcomes data were obtained through the CIBMTR research database. All participants provided informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the National Marrow Donor Program institutional review board. Included were patients aged ≥18 years with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and MDS undergoing their first HCT from January 2017 through December 2021. Detailed selection criteria are provided in supplemental Table 1. MUDs were matched at the allele level at HLA-A, -B, -C, and -DRB1, and haplo donors were mismatched at ≥2 HLA loci. All patients received PTCy-containing GVHD prophylaxis. Patients who received CD34+-selected peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts, ruxolitinib, abatacept, and in vivo T-cell depleting agents such as antithymocyte globulin or alemtuzumab for GVHD prophylaxis were excluded.

Biostatistical methods

Primary objectives were to compare OS and GRFS between MUDs and haplo donors. OS was defined as the time from transplant to death from any cause. GRFS was defined as survival without grade 3/4 acute GVHD (aGVHD), moderate-severe chronic GVHD (cGVHD) requiring immunosuppressive treatment, or disease relapse. Unadjusted probabilities of OS and GRFS were estimated with Kaplan-Meier curves.14 Cox regression was used to examine the independent effect of MUD HCT vs haplo-HCT using a priori clinically selected factors as potential confounders such as disease risk index (DRI) disease, HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI), Karnofsky performance score at baseline, conditioning regimen intensity, graft source, donor/recipient cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, age at HCT (continuous or categorical), donor age (continuous or categorical), race, sex, time from diagnosis to transplant, and year of HCT.15

Secondary end points included neutrophil and platelet engraftment, cumulative incidence rates of primary graft failure, aGVHD and cGVHD, relapse, disease-free survival (DFS), and nonrelapse mortality (NRM).16 Proportions, cumulative incidence, and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate probabilities of secondary end points. Patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression were censored at last follow-up. Similar to the primary end points, multiple regression models using logistic regression, Cox regression, or Fine and Gray regression were used to examine the independent effect of donor type on the secondary end points. Interactions between donor type and all regression model factors were tested against a stringent P value <.01 to limit the type-1 error given the large number of tests. Precision of estimates was measured with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P value <.05 were considered statistically significant.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on the primary end points (GRFS and OS) using propensity score weights. We applied inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using stabilized weights based on propensity scores to balance observed baseline characteristics between the MUD and haplo groups.17 Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression including all clinically relevant covariates selected a priori. We evaluated covariate balance using absolute standardized mean differences, retaining covariates with absolute standardized mean differences of >0.10 in the final models. Weighted Cox proportional hazards models were then fitted for GRFS and OS using robust sandwich-style variance estimators to compute 95% confidence limits. Definitions of secondary outcomes and detailed biostatistical methods are included in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Patient and donor demographics

The final patient cohort consisted of 5873 patients (MUD, n = 1973; and haplo, n = 3900) from 143 US centers (Table 1). Median follow-up was 36.3 months (range, 3.2-79.1). Median time from diagnosis to HCT did not differ between the groups (6.2 months; range, 0.4-417.2). MUD recipients were older (aged 62.1 vs 58.8 years; range, 18-82.2) and donors were younger in the MUD cohort (aged 27.5 years; range, 18.0-60.9) than the haplo cohort (aged 35.7 years; range, 18-74.1). The MUD cohort also included a higher proportion of patients with NHW ancestry (86.4% vs 59.0%). AML was the most common disease (MUD, 54.7%; and haplo, 55.3%), and PBSCs was the most common used graft in both groups. However, bone marrow grafts were more frequently used for haplo-HCT compared with MUD HCT (18% vs 7%). RIC regimens were used in ∼60% of patients in both groups. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine (Flu) was the predominant RIC regimen accounting for ∼70% of haplo-HCT, whereas Flu and melphalan (Mel) was commonly used for MUD in ∼40%. Among MAC regimens, haplo-HCT recipients commonly received Flu with TBI (45.9%), whereas patients in the MUD group frequently received busulfan and Flu (54%). All patients received PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis, with most receiving PTCy with a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus or cyclosporine) and MMF, with 1% receiving MTX in each arm.

Characteristics of adult patients receiving HLA MUD allogeneic HCT and haplo-HCT for AML/ALL/MDS in the United States between 2017 and 2021

| Characteristic . | HLA MUD . | Haplo donor . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 1973 | 3900 | 5873 |

| Centers, n | 104 | 140 | 143 |

| Age, median (range), y | 62.1 (18.0-82.2) | 58.8 (18.0-82.0) | 60.0 (18.0-82.2) |

| 18-29 | 125 (6.3) | 451 (11.6) | 576 (9.8) |

| 30-49 | 375 (19.0) | 807 (20.7) | 1182 (20.1) |

| 50-59 | 332 (16.8) | 839 (21.5) | 1171 (19.9) |

| 60-65 | 463 (23.5) | 767 (19.7) | 1230 (20.9) |

| 66-69 | 358 (18.1) | 554 (14.2) | 912 (15.5) |

| 70-74 | 277 (14.0) | 404 (10.4) | 681 (11.6) |

| ≥75 | 43 (2.2) | 78 (2.0) | 121 (2.1) |

| Donor age, median (min-max), y | 27.5 (18.0-60.9) | 35.7 (18.0-74.1) | 32.2 (18.0-74.1) |

| 18-24 | 647 (32.8) | 603 (15.5) | 1250 (21.3) |

| 25-29 | 633 (32.1) | 614 (15.7) | 1247 (21.2) |

| 30-34 | 303 (15.4) | 636 (16.3) | 939 (16.0) |

| 35-39 | 192 (9.7) | 642 (16.5) | 834 (14.2) |

| 40-44 | 85 (4.3) | 487 (12.5) | 572 (9.7) |

| 45-49 | 61 (3.1) | 345 (8.8) | 406 (6.9) |

| 50-54 | 30 (1.5) | 222 (5.7) | 252 (4.3) |

| 55-59 | 20 (1.0) | 156 (4.0) | 176 (3.0) |

| ≥60 | 2 (0.1) | 195 (5.0) | 197 (3.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1178 (59.7) | 2317 (59.4) | 3495 (59.5) |

| Female | 795 (40.3) | 1583 (40.6) | 2378 (40.5) |

| Donor/recipient ABO match, n (%) | |||

| Matched | 1059 (53.7) | 1737 (44.5) | 2796 (47.6) |

| Minor mismatch | 353 (17.9) | 427 (10.9) | 780 (13.3) |

| Major mismatch | 253 (12.8) | 389 (10.0) | 642 (10.9) |

| Bidirectional | 64 (3.2) | 91 (2.3) | 155 (2.6) |

| Not reported/missing | 244 (12.4) | 1256 (32.2) | 1500 (25.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| NHW | 1704 (86.4) | 2301 (59.0) | 4005 (68.2) |

| Hispanic | 76 (3.9) | 492 (12.6) | 568 (9.7) |

| Black | 54 (2.7) | 569 (14.6) | 623 (10.6) |

| Asian | 49 (2.5) | 231 (5.9) | 280 (4.8) |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 (0.0) | 13 (0.3) | 13 (0.2) |

| American Indian | 7 (0.4) | 24 (0.6) | 31 (0.5) |

| >1 Race | 5 (0.3) | 28 (0.7) | 33 (0.6) |

| Missing | 78 (4.0) | 242 (6.2) | 320 (5.4) |

| HCT-CI, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 352 (17.8) | 747 (19.2) | 1099 (18.7) |

| 1 | 304 (15.4) | 597 (15.3) | 901 (15.3) |

| 2 | 328 (16.6) | 620 (15.9) | 948 (16.1) |

| ≥3 | 989 (50.1) | 1936 (49.6) | 2925 (49.8) |

| Karnofsky performance score at admission, n (%) | |||

| 90%-100% | 1027 (52.1) | 2029 (52.0) | 3056 (52.0) |

| <90% | 895 (45.4) | 1796 (46.1) | 2691 (45.8) |

| Not reported | 51 (2.6) | 75 (1.9) | 126 (2.1) |

| Disease, n (%) | |||

| AML | 1080 (54.7) | 2157 (55.3) | 3237 (55.1) |

| ALL | 290 (14.7) | 830 (21.3) | 1120 (19.1) |

| MDS | 603 (30.6) | 913 (23.4) | 1516 (25.8) |

| Refined DRI, n (%) | |||

| Low | 68 (3.4) | 139 (3.6) | 207 (3.5) |

| Intermediate | 1311 (66.4) | 2535 (65.0) | 3846 (65.5) |

| High | 532 (27.0) | 1097 (28.1) | 1629 (27.7) |

| Very high | 36 (1.8) | 104 (2.7) | 140 (2.4) |

| MDS (unknown DRI) | 26 (1.3) | 25 (0.6) | 51 (0.9) |

| Graft source, n(%) | |||

| Bone marrow | 138 (7.0) | 723 (18.5) | 861 (14.7) |

| PBSCs | 1835 (93.0) | 3177 (81.5) | 5012 (85.3) |

| Donor/recipient CMV status, n (%) | |||

| +/+ | 552 (28.0) | 1614 (41.4) | 2166 (36.9) |

| +/− | 212 (10.7) | 370 (9.5) | 582 (9.9) |

| −/+ | 677 (34.3) | 1049 (26.9) | 1726 (29.4) |

| −/− | 522 (26.5) | 844 (21.6) | 1366 (23.3) |

| Not reported | 10 (0.5) | 23 (0.6) | 33 (0.6) |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | |||

| Myeloablative | 797 (40.4) | 1485 (38.1) | 2282 (38.9) |

| NMA/RIC | 1176 (59.6) | 2415 (61.9) | 3591 (61.1) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis - no. (%) | |||

| PTCy + TAC ± MTX or MMF | 1596 (80.9) | 3472 (89.0) | 5068 (86.3) |

| PTCy + CsA ± MTX or MMF | 153 (7.8) | 107 (2.7) | 260 (4.4) |

| PTCy + TAC + sirolimus ± MTX or MMF | 65 (3.3) | 42 (1.1) | 107 (1.8) |

| PTCy + CsA + sirolimus ± MTX or MMF | 39 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (0.7) |

| PTCy + sirolimus ± MMF or MTX without TAC/CsA | 106 (5.4) | 268 (6.9) | 374 (6.4) |

| PTCy ± MTX/MMF without TAC/CsA | 14 (0.7) | 11 (0.3) | 25 (0.4) |

| Year of transplant, n (%) | |||

| 2017 | 126 (6.4) | 580 (14.9) | 706 (12.0) |

| 2018 | 280 (14.2) | 740 (19.0) | 1020 (17.4) |

| 2019 | 433 (21.9) | 766 (19.6) | 1199 (20.4) |

| 2020 | 539 (27.3) | 905 (23.2) | 1444 (24.6) |

| 2021 | 595 (30.2) | 909 (23.3) | 1504 (25.6) |

| DX to HCT, months, median (range) | 6.2 (0.4-350.8) | 6.2 (0.6-417.2) | 6.2 (0.4-417.2) |

| Follow-up, months, median (range) | 35.9 (3.4-74.8) | 36.6 (3.2-79.1) | 36.3 (3.2-79.1) |

| Characteristic . | HLA MUD . | Haplo donor . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 1973 | 3900 | 5873 |

| Centers, n | 104 | 140 | 143 |

| Age, median (range), y | 62.1 (18.0-82.2) | 58.8 (18.0-82.0) | 60.0 (18.0-82.2) |

| 18-29 | 125 (6.3) | 451 (11.6) | 576 (9.8) |

| 30-49 | 375 (19.0) | 807 (20.7) | 1182 (20.1) |

| 50-59 | 332 (16.8) | 839 (21.5) | 1171 (19.9) |

| 60-65 | 463 (23.5) | 767 (19.7) | 1230 (20.9) |

| 66-69 | 358 (18.1) | 554 (14.2) | 912 (15.5) |

| 70-74 | 277 (14.0) | 404 (10.4) | 681 (11.6) |

| ≥75 | 43 (2.2) | 78 (2.0) | 121 (2.1) |

| Donor age, median (min-max), y | 27.5 (18.0-60.9) | 35.7 (18.0-74.1) | 32.2 (18.0-74.1) |

| 18-24 | 647 (32.8) | 603 (15.5) | 1250 (21.3) |

| 25-29 | 633 (32.1) | 614 (15.7) | 1247 (21.2) |

| 30-34 | 303 (15.4) | 636 (16.3) | 939 (16.0) |

| 35-39 | 192 (9.7) | 642 (16.5) | 834 (14.2) |

| 40-44 | 85 (4.3) | 487 (12.5) | 572 (9.7) |

| 45-49 | 61 (3.1) | 345 (8.8) | 406 (6.9) |

| 50-54 | 30 (1.5) | 222 (5.7) | 252 (4.3) |

| 55-59 | 20 (1.0) | 156 (4.0) | 176 (3.0) |

| ≥60 | 2 (0.1) | 195 (5.0) | 197 (3.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1178 (59.7) | 2317 (59.4) | 3495 (59.5) |

| Female | 795 (40.3) | 1583 (40.6) | 2378 (40.5) |

| Donor/recipient ABO match, n (%) | |||

| Matched | 1059 (53.7) | 1737 (44.5) | 2796 (47.6) |

| Minor mismatch | 353 (17.9) | 427 (10.9) | 780 (13.3) |

| Major mismatch | 253 (12.8) | 389 (10.0) | 642 (10.9) |

| Bidirectional | 64 (3.2) | 91 (2.3) | 155 (2.6) |

| Not reported/missing | 244 (12.4) | 1256 (32.2) | 1500 (25.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| NHW | 1704 (86.4) | 2301 (59.0) | 4005 (68.2) |

| Hispanic | 76 (3.9) | 492 (12.6) | 568 (9.7) |

| Black | 54 (2.7) | 569 (14.6) | 623 (10.6) |

| Asian | 49 (2.5) | 231 (5.9) | 280 (4.8) |

| Native Hawaiian | 0 (0.0) | 13 (0.3) | 13 (0.2) |

| American Indian | 7 (0.4) | 24 (0.6) | 31 (0.5) |

| >1 Race | 5 (0.3) | 28 (0.7) | 33 (0.6) |

| Missing | 78 (4.0) | 242 (6.2) | 320 (5.4) |

| HCT-CI, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 352 (17.8) | 747 (19.2) | 1099 (18.7) |

| 1 | 304 (15.4) | 597 (15.3) | 901 (15.3) |

| 2 | 328 (16.6) | 620 (15.9) | 948 (16.1) |

| ≥3 | 989 (50.1) | 1936 (49.6) | 2925 (49.8) |

| Karnofsky performance score at admission, n (%) | |||

| 90%-100% | 1027 (52.1) | 2029 (52.0) | 3056 (52.0) |

| <90% | 895 (45.4) | 1796 (46.1) | 2691 (45.8) |

| Not reported | 51 (2.6) | 75 (1.9) | 126 (2.1) |

| Disease, n (%) | |||

| AML | 1080 (54.7) | 2157 (55.3) | 3237 (55.1) |

| ALL | 290 (14.7) | 830 (21.3) | 1120 (19.1) |

| MDS | 603 (30.6) | 913 (23.4) | 1516 (25.8) |

| Refined DRI, n (%) | |||

| Low | 68 (3.4) | 139 (3.6) | 207 (3.5) |

| Intermediate | 1311 (66.4) | 2535 (65.0) | 3846 (65.5) |

| High | 532 (27.0) | 1097 (28.1) | 1629 (27.7) |

| Very high | 36 (1.8) | 104 (2.7) | 140 (2.4) |

| MDS (unknown DRI) | 26 (1.3) | 25 (0.6) | 51 (0.9) |

| Graft source, n(%) | |||

| Bone marrow | 138 (7.0) | 723 (18.5) | 861 (14.7) |

| PBSCs | 1835 (93.0) | 3177 (81.5) | 5012 (85.3) |

| Donor/recipient CMV status, n (%) | |||

| +/+ | 552 (28.0) | 1614 (41.4) | 2166 (36.9) |

| +/− | 212 (10.7) | 370 (9.5) | 582 (9.9) |

| −/+ | 677 (34.3) | 1049 (26.9) | 1726 (29.4) |

| −/− | 522 (26.5) | 844 (21.6) | 1366 (23.3) |

| Not reported | 10 (0.5) | 23 (0.6) | 33 (0.6) |

| Conditioning intensity, n (%) | |||

| Myeloablative | 797 (40.4) | 1485 (38.1) | 2282 (38.9) |

| NMA/RIC | 1176 (59.6) | 2415 (61.9) | 3591 (61.1) |

| GVHD Prophylaxis - no. (%) | |||

| PTCy + TAC ± MTX or MMF | 1596 (80.9) | 3472 (89.0) | 5068 (86.3) |

| PTCy + CsA ± MTX or MMF | 153 (7.8) | 107 (2.7) | 260 (4.4) |

| PTCy + TAC + sirolimus ± MTX or MMF | 65 (3.3) | 42 (1.1) | 107 (1.8) |

| PTCy + CsA + sirolimus ± MTX or MMF | 39 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (0.7) |

| PTCy + sirolimus ± MMF or MTX without TAC/CsA | 106 (5.4) | 268 (6.9) | 374 (6.4) |

| PTCy ± MTX/MMF without TAC/CsA | 14 (0.7) | 11 (0.3) | 25 (0.4) |

| Year of transplant, n (%) | |||

| 2017 | 126 (6.4) | 580 (14.9) | 706 (12.0) |

| 2018 | 280 (14.2) | 740 (19.0) | 1020 (17.4) |

| 2019 | 433 (21.9) | 766 (19.6) | 1199 (20.4) |

| 2020 | 539 (27.3) | 905 (23.2) | 1444 (24.6) |

| 2021 | 595 (30.2) | 909 (23.3) | 1504 (25.6) |

| DX to HCT, months, median (range) | 6.2 (0.4-350.8) | 6.2 (0.6-417.2) | 6.2 (0.4-417.2) |

| Follow-up, months, median (range) | 35.9 (3.4-74.8) | 36.6 (3.2-79.1) | 36.3 (3.2-79.1) |

CsA, cyclosporine; DX, diagnosis; NMA, non-myeloablative; TAC, tacrolimus.

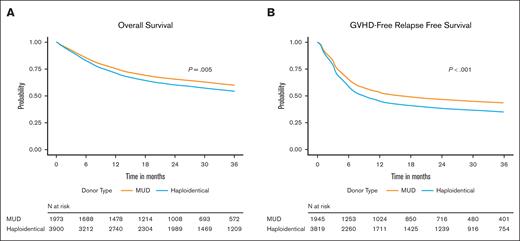

OS and GRFS

Our primary end points were OS and GRFS. The 3-year OS rates were 59.2% (95% CI, 56.8-61.5) and 54.9% (95% CI, 53.2-56.5) in the MUD and haplo groups, respectively (supplemental Table 2A). In multivariable analysis (MVA), compared with MUD HCT, the risk of overall mortality at 3 years was higher in the haplo group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.27; P = .005; Table 2; Figure 1A). Refined DRI, HCT-CI, Karnofsky performance score, recipient age, graft source, recipient sex, and time from diagnosis to transplant were other recipient-, disease-, and transplant-related factors associated with 3-year OS on multiple regression analysis. Donor age and donor-recipient CMV serostatus were significant donor-related predictors of OS, independent of donor type (Table 2).

Multiple regression analysis of 3-year OS adjusted for significant covariates

| Covariate . | N . | HR of mortality (95% CI) . | P value . | Overall 3-year P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | ||||

| URD 8/8 | 1972 | 1.00 (reference) | .005 | |

| Haploidentical | 3898 | 1.15 (1.04-1.27) | .005 | |

| Refined DRI | ||||

| Low | 207 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| Intermediate | 3846 | 1.55 (1.15-2.09) | .004 | |

| High/very high | 1766 | 2.90 (2.14-3.92) | <.001 | |

| MDS (DRI N/A) | 51 | 1.58 (0.90-2.78) | .110 | |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| 0 | 1099 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| 1 | 884 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | .771 | |

| 2 | 917 | 1.19 (1.02-1.38) | .027 | |

| 3 | 1048 | 1.36 (1.18-1.57) | <.001 | |

| 4 | 809 | 1.68 (1.45-1.94) | <.001 | |

| 5 | 469 | 1.57 (1.32-1.86) | <.001 | |

| ≥6 | 644 | 2.00 (1.72-2.33) | <.001 | |

| Age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.15 (1.11-1.19) | <.001 | ||

| Donor age at HCT, y | ||||

| 18-30 | 2518 | 1.00 (reference) | .021 | |

| 31-40 | 1765 | 1.09 (0.98-1.20) | .097 | |

| ≥41 | 1587 | 1.16 (1.04-1.29) | .006 | |

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||||

| +/+ | 2164 | 1.00 (reference) | .001 | |

| +/− | 582 | 0.90 (0.77-1.04) | .164 | |

| −/+ | 1725 | 1.00 (0.91-1.11) | .992 | |

| −/− | 1366 | 0.82 (0.73-0.92) | <.001 | |

| Not reported | 33 | 1.37 (0.85-2.22) | .201 | |

| Race | ||||

| NHW | 4324 | 1.00 (reference) | .535 | |

| Hispanic | 567 | 0.92 (0.79-1.08) | ||

| Black or African American | 622 | 0.94 (0.82-1.07) | ||

| Asian | 280 | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | ||

| Other | 77 | 1.09 (0.76-1.57) | ||

| Graft source | ||||

| Bone marrow | 860 | 1.00 (reference) | .010 | |

| PBSCs | 5010 | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | .010 | |

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2017 | 706 | 1.00 (reference) | .951 | |

| 2018 | 1020 | 1.01 (0.87-1.17) | ||

| 2019 | 1197 | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | ||

| 2020 | 1443 | 1.03 (0.90-1.18) | ||

| 2021 | 1504 | 0.98 (0.85-1.13) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3494 | 1.00 (reference) | .003 | |

| Female | 2376 | 0.88 (0.81-0.96) | .003 | |

| Karnofsky performance score | ||||

| 90-100 | 3054 | 1.00 (reference) | .005 | |

| <90 | 2690 | 1.15 (1.06-1.25) | .001 | |

| Missing/not reported | 126 | 1.04 (0.78-1.39) | .809 | |

| Time from DX to TX | ||||

| <6 months | 2814 | 1.00 (reference) | .001 | |

| 6 months to 1 year | 1740 | 1.12 (1.02-1.23) | .016 | |

| 1-2 years | 741 | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | .282 | |

| >2 years | 575 | 0.84 (0.73-0.98) | .024 |

| Covariate . | N . | HR of mortality (95% CI) . | P value . | Overall 3-year P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | ||||

| URD 8/8 | 1972 | 1.00 (reference) | .005 | |

| Haploidentical | 3898 | 1.15 (1.04-1.27) | .005 | |

| Refined DRI | ||||

| Low | 207 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| Intermediate | 3846 | 1.55 (1.15-2.09) | .004 | |

| High/very high | 1766 | 2.90 (2.14-3.92) | <.001 | |

| MDS (DRI N/A) | 51 | 1.58 (0.90-2.78) | .110 | |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| 0 | 1099 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| 1 | 884 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | .771 | |

| 2 | 917 | 1.19 (1.02-1.38) | .027 | |

| 3 | 1048 | 1.36 (1.18-1.57) | <.001 | |

| 4 | 809 | 1.68 (1.45-1.94) | <.001 | |

| 5 | 469 | 1.57 (1.32-1.86) | <.001 | |

| ≥6 | 644 | 2.00 (1.72-2.33) | <.001 | |

| Age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.15 (1.11-1.19) | <.001 | ||

| Donor age at HCT, y | ||||

| 18-30 | 2518 | 1.00 (reference) | .021 | |

| 31-40 | 1765 | 1.09 (0.98-1.20) | .097 | |

| ≥41 | 1587 | 1.16 (1.04-1.29) | .006 | |

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||||

| +/+ | 2164 | 1.00 (reference) | .001 | |

| +/− | 582 | 0.90 (0.77-1.04) | .164 | |

| −/+ | 1725 | 1.00 (0.91-1.11) | .992 | |

| −/− | 1366 | 0.82 (0.73-0.92) | <.001 | |

| Not reported | 33 | 1.37 (0.85-2.22) | .201 | |

| Race | ||||

| NHW | 4324 | 1.00 (reference) | .535 | |

| Hispanic | 567 | 0.92 (0.79-1.08) | ||

| Black or African American | 622 | 0.94 (0.82-1.07) | ||

| Asian | 280 | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | ||

| Other | 77 | 1.09 (0.76-1.57) | ||

| Graft source | ||||

| Bone marrow | 860 | 1.00 (reference) | .010 | |

| PBSCs | 5010 | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | .010 | |

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2017 | 706 | 1.00 (reference) | .951 | |

| 2018 | 1020 | 1.01 (0.87-1.17) | ||

| 2019 | 1197 | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | ||

| 2020 | 1443 | 1.03 (0.90-1.18) | ||

| 2021 | 1504 | 0.98 (0.85-1.13) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3494 | 1.00 (reference) | .003 | |

| Female | 2376 | 0.88 (0.81-0.96) | .003 | |

| Karnofsky performance score | ||||

| 90-100 | 3054 | 1.00 (reference) | .005 | |

| <90 | 2690 | 1.15 (1.06-1.25) | .001 | |

| Missing/not reported | 126 | 1.04 (0.78-1.39) | .809 | |

| Time from DX to TX | ||||

| <6 months | 2814 | 1.00 (reference) | .001 | |

| 6 months to 1 year | 1740 | 1.12 (1.02-1.23) | .016 | |

| 1-2 years | 741 | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | .282 | |

| >2 years | 575 | 0.84 (0.73-0.98) | .024 |

DX, diagnosis; N/A, not assignable; TX, treatment; URD, unrelated donor.

Impact of donor type on overall and GVHD-free, relapse-free survival. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and GRFS (B) in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Impact of donor type on overall and GVHD-free, relapse-free survival. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS (A) and GRFS (B) in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Approximately 42% of the haplo donor graft recipients and 38% of the MUD recipients died. The most common cause of death in both donor groups was relapse of the underlying malignancy, however, the proportion was lower in the haplo than the MUD group (45% vs 49%). The second most common reason for death was infections in the haplo group, and organ failure in the MUD group (15% for both). GVHD was the cause of death in 6% and 4% of haplo-HCT and MUD HCT, respectively (supplemental Table 2C).

The 3-year GRFS rates were higher for the MUD group, 42.4% (95% CI, 40.1-44.7) than for the haplo group, 35.6% (95% CI, 34.1-37.2; supplemental Table 2B). MVA analysis noted the recipients of haplo donor grafts to be more likely to experience a GRFS event at 3 years (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.10-1.29; P < .001) compared with recipients of MUD grafts (Table 3; Figure 1B). DRI, HCT-CI, and recipient age were other recipient- and disease-related factors associated with 3-year GRFS. Donor age and donor-recipient CMV serostatus persisted as significant donor-related predictors of GRFS, independent of donor type (Table 3).

Multiple regression analysis of 3-year GRFS adjusted for significant covariates

| Covariate . | N . | HR of GRFS event (95% CI) . | P value . | Overall 3-year P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | 1944 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| URD 8/8 | ||||

| Haploidentical | 3817 | 1.19 (1.10-1.29) | <.001 | |

| Refined DRI | ||||

| Low | 203 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| Intermediate | 3767 | 1.32 (1.06-1.64) | .012 | |

| High/very high | 1741 | 2.20 (1.77-2.74) | <.001 | |

| MDS (DRI N/A) | 50 | 2.11 (1.41-3.15) | <.001 | |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| 0 | 1069 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| 1 | 872 | 1.05 (0.93-1.18) | .456 | |

| 2 | 904 | 1.10 (0.97-1.24) | .124 | |

| 3 | 1023 | 1.21 (1.08-1.36) | .001 | |

| 4 | 794 | 1.38 (1.22-1.56) | <.001 | |

| 5 | 462 | 1.36 (1.18-1.57) | <.001 | |

| ≥6 | 637 | 1.56 (1.38-1.77) | <.001 | |

| Age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 | ||

| Donor age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 | ||

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||||

| +/+ | 2123 | 1.00 (reference) | .003 | |

| +/− | 571 | 0.92 (0.81-1.04) | .181 | |

| −/+ | 1687 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | .868 | |

| −/− | 1348 | 0.87 (0.79-0.95) | .003 | |

| Not reported | 32 | 1.46 (0.96-2.21) | .073 | |

| Race | ||||

| NHW | 4243 | 1.00 (reference) | .140 | |

| Hispanic | 554 | 0.93 (0.82-1.06) | ||

| Black or African American | 612 | 0.99 (0.88-1.10) | ||

| Asian | 278 | 0.83 (0.70-0.98) | ||

| Other | 74 | 1.17 (0.87-1.57) | ||

| Graft source | ||||

| Bone marrow | 841 | 1.00 (reference) | .933 | |

| PBSCs | 4920 | 1.00 (0.90-1.10) | ||

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2017 | 698 | 1.00 (reference) | .892 | |

| 2018 | 1002 | 0.98 (0.87-1.11) | ||

| 2019 | 1181 | 0.94 (0.84-1.06) | ||

| 2020 | 1420 | 0.97 (0.87-1.09) | ||

| 2021 | 1460 | 0.98 (0.87-1.10) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3432 | 1.00 (reference) | .090 | |

| Female | 2329 | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | ||

| Karnofsky performance score | ||||

| 90-100 | 2990 | 1.00 (reference) | .055 | |

| <90 | 2647 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) | ||

| Missing/not reported | 124 | 0.89 (0.69-1.15) | ||

| Time from DX to TX | ||||

| <6 months | 2758 | 1.00 (reference) | .080 | |

| 6 months to 1 year | 1711 | 1.09 (1.01-1.18) | ||

| 1-2 years | 732 | 1.07 (0.96-1.18) | ||

| >2 years | 560 | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) |

| Covariate . | N . | HR of GRFS event (95% CI) . | P value . | Overall 3-year P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor type | 1944 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| URD 8/8 | ||||

| Haploidentical | 3817 | 1.19 (1.10-1.29) | <.001 | |

| Refined DRI | ||||

| Low | 203 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| Intermediate | 3767 | 1.32 (1.06-1.64) | .012 | |

| High/very high | 1741 | 2.20 (1.77-2.74) | <.001 | |

| MDS (DRI N/A) | 50 | 2.11 (1.41-3.15) | <.001 | |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| 0 | 1069 | 1.00 (reference) | <.001 | |

| 1 | 872 | 1.05 (0.93-1.18) | .456 | |

| 2 | 904 | 1.10 (0.97-1.24) | .124 | |

| 3 | 1023 | 1.21 (1.08-1.36) | .001 | |

| 4 | 794 | 1.38 (1.22-1.56) | <.001 | |

| 5 | 462 | 1.36 (1.18-1.57) | <.001 | |

| ≥6 | 637 | 1.56 (1.38-1.77) | <.001 | |

| Age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 | ||

| Donor age at HCT (per decade), Continuous | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 | ||

| Donor/recipient CMV status | ||||

| +/+ | 2123 | 1.00 (reference) | .003 | |

| +/− | 571 | 0.92 (0.81-1.04) | .181 | |

| −/+ | 1687 | 1.01 (0.93-1.10) | .868 | |

| −/− | 1348 | 0.87 (0.79-0.95) | .003 | |

| Not reported | 32 | 1.46 (0.96-2.21) | .073 | |

| Race | ||||

| NHW | 4243 | 1.00 (reference) | .140 | |

| Hispanic | 554 | 0.93 (0.82-1.06) | ||

| Black or African American | 612 | 0.99 (0.88-1.10) | ||

| Asian | 278 | 0.83 (0.70-0.98) | ||

| Other | 74 | 1.17 (0.87-1.57) | ||

| Graft source | ||||

| Bone marrow | 841 | 1.00 (reference) | .933 | |

| PBSCs | 4920 | 1.00 (0.90-1.10) | ||

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2017 | 698 | 1.00 (reference) | .892 | |

| 2018 | 1002 | 0.98 (0.87-1.11) | ||

| 2019 | 1181 | 0.94 (0.84-1.06) | ||

| 2020 | 1420 | 0.97 (0.87-1.09) | ||

| 2021 | 1460 | 0.98 (0.87-1.10) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 3432 | 1.00 (reference) | .090 | |

| Female | 2329 | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | ||

| Karnofsky performance score | ||||

| 90-100 | 2990 | 1.00 (reference) | .055 | |

| <90 | 2647 | 1.08 (1.01-1.15) | ||

| Missing/not reported | 124 | 0.89 (0.69-1.15) | ||

| Time from DX to TX | ||||

| <6 months | 2758 | 1.00 (reference) | .080 | |

| 6 months to 1 year | 1711 | 1.09 (1.01-1.18) | ||

| 1-2 years | 732 | 1.07 (0.96-1.18) | ||

| >2 years | 560 | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) |

The model was stratified by conditioning intensity.

DX, diagnosis; N/A, not assignable; TX, treatment; URD, unrelated donor.

Sensitivity analysis for OS and GRFS

To address any imbalance between the 2 donor types, including donor age and graft source, we performed a sensitivity analysis using IPTW adjustment (supplemental Figure 1A-B). This analysis corroborated the previous results with multivariable models showing haplo-HCT was associated with worse OS (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.01-1.19; P = .025) and GRFS (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06-1.21; P < .001).

Effect of disease on outcomes

Previous studies have noted differential effects of donor type by disease.18,19 We conducted an unplanned subanalysis by disease (ALL, AML, and MDS) for the primary outcomes. OS was worse with haplo-HCT compared with MUD HCT among patients with MDS (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.12-1.62; P = .001), whereas no difference in OS was noted among those with AML (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00-1.30; P = .058) and patients with ALL (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.70-1.19; P = .508; supplemental Table 4F. GRFS was worse with haplo donors among patients with AML (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03-1.28; P = .016) and those with MDS (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.21-1.62; P < .001), but was similar to that for MUD HCT among patients with ALL (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.85-1.29; P = .663; supplemental Table 4G).

Effect of conditioning intensity on outcomes

In previous studies, survival outcomes differed between donor types, based on conditioning intensity.11 Therefore, we examined this effect in our cohort. In MVA, MAC was associated with an increased mortality risk in haplo-HCT, compared with MUD HCT (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04-1.45; P = .018). Conversely, OS was not different with RIC between the donor types (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.27; P = .06; supplemental Tables 3A and 4A). Haplo-HCT was associated with worse GRFS irrespective of conditioning intensity (MAC: HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.48; P < .001), (RIC: HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.27; P = .008; supplemental Tables 3B and 4B). Relapse did not differ between groups based on conditioning intensity (MAC: HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.81-1.18; P = .807; RIC: HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.81-1.07; P = .300), however, NRM remained worse in the haplo-HCT group (MAC: HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.22-1.91; P = .005; RIC: HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.08-1.61; P = .007; supplemental Tables 3C and 4C).

Multiple regression analysis restricted to Flu/Mel with or without TBI found no difference between donor types when TBI was used (OS: HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.76-1.95; P = .417; and GRFS: HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 0.96-2.26; P = .073), but found worse OS and GRFS in haplo-HCT without the use of TBI (OS: HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.30-2.53; P < .001; and GRFS: HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.16-2.14; P = .003), favoring MUD HCT over haplo-HCT when RIC with Flu and Mel are used without TBI (supplemental Table 4C-D).

Effect of donor age on outcomes

We noted marked differences in donor age between the donor types, with the median age of MUDs substantially lower than haplo donors. Given that donor age is a known significant predictor of survival, we performed an unplanned subgroup analysis restricting donor age to <30 years (supplemental Table 6A-D). Restricted to younger donors, there was no difference in OS between donor types (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.97-1.30; P = .132) regardless of conditioning intensity. GRFS (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01-1.30; P = .032) and NRM (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.19-1.91; P < .001) remained worse in the haplo group. However, younger haplo donors were associated with lower risk of relapse than younger MUDs (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.98; P = .028; supplemental Table 6C-D).

Analysis of secondary end points

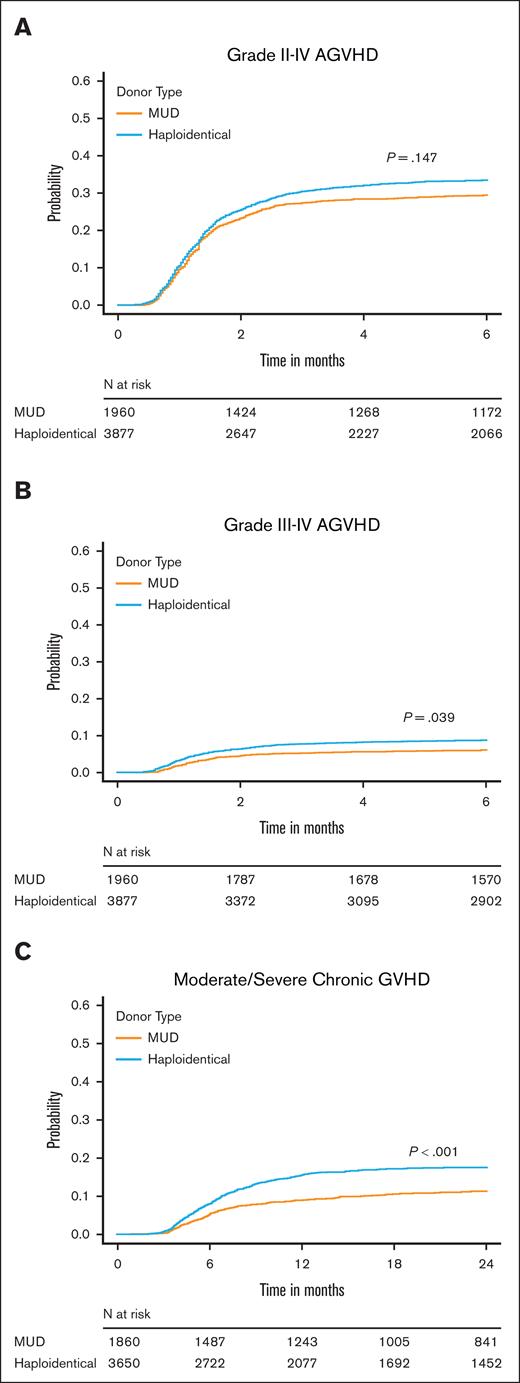

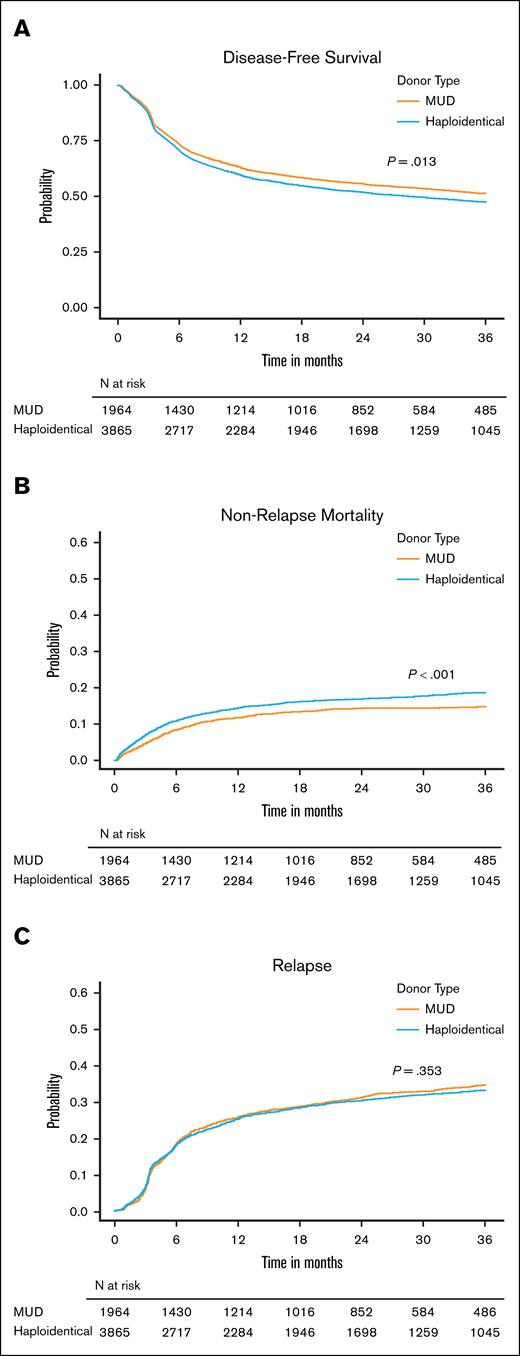

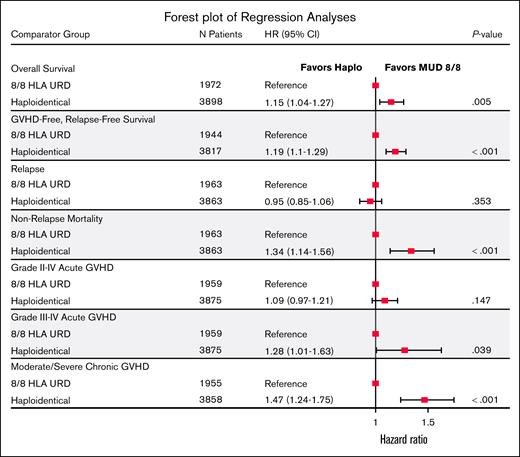

Our secondary end points of interest were aGVHD and cGVHD, NRM, DFS, and relapse. In MVA, although the risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD by 6 months was similar between the donor types, recipients of haplo-HCT had a higher risk of grade 3/4 aGVHD at 6 months (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.01-1.63; P = .039) and moderate to severe cGVHD by 24 months (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.24-1.75; P < .001; supplemental Table 5A-C; Figure 2). Haplo-HCT was associated with higher risk of NRM (HR, 1.34; P < .001) leading to a lower 3-year DFS (HR, 1.12; P = .013) than MUD HCT. However, relapse risk did not differ between donor types (HR, 0.95; P = .353; supplemental Table 5D-E; Figure 3). Primary graft failure was significantly higher in the haplo group (HR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.21-2.30; P = .002), and this remained true when restricted to HCT with PBSC grafts (supplemental Table 5F). A forest plot of multiple regression models for all end points is shown in Figure 4. We performed several unplanned exploratory analyses, which included analysis of center effect, conditioning intensity regimens, disease, and NHW (supplemental Tables 4C-D and 6-9).

Impact of donor type on acute and chronic GVHD. Cumulative incidence of (A) grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, (B) grade 3/4 aGVHD, and (C) moderate/severe cGVHD in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Impact of donor type on acute and chronic GVHD. Cumulative incidence of (A) grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, (B) grade 3/4 aGVHD, and (C) moderate/severe cGVHD in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Impact of donor type on disease-free survival, nonrelapse mortality and relapse. Cumulative incidence of DFS (A), NRM (B), and relapse (C) in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Impact of donor type on disease-free survival, nonrelapse mortality and relapse. Cumulative incidence of DFS (A), NRM (B), and relapse (C) in recipients of MUD HCT or haplo-HCT.

Forest plot results of the multivariable adjusted risk of primary and secondary end points comparing MUD HCT (reference) with haplo-HCT. URD, unrelated donor.

Forest plot results of the multivariable adjusted risk of primary and secondary end points comparing MUD HCT (reference) with haplo-HCT. URD, unrelated donor.

Discussion

PTCy is increasingly being used for GVHD prophylaxis across multiple donor types. We used the CIBMTR database to perform, what is, to our knowledge, the largest and most contemporary observational study to date comparing outcomes of recipients of MUD-HCT and haplo-HCT using a PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis regimen. We found that although overall outcomes are encouraging with both donor sources, OS and GRFS were better with MUD HCT than with haplo-HCT. This was mainly due to decreased NRM, severe acute, and moderate-to-severe cGVHD in MUD HCT recipients.

A smaller European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) study in patients who received transplantation before 2018 compared outcomes of patients with AML who received MRD HCT, MUD HCT, or haplo-HCT using PTCy and reported no differences in OS, leukemia-free survival, or GRFS. The haplo-HCT cohort had a significantly increased risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD and NRM, but lower risk of relapse.19 Unlike the EBMT study, in our study the relapse rate was not different between the MUD and haplo cohorts. This could be explained by differences in GVHD prophylaxis and conditioning regimen, because most EBMT study patients in the haplo group received PTCy with 2 immunosuppressive agents, whereas those in the MSD and MUD groups received PTCy alone or with another immunosuppressive agent. In addition, a minority of patients in the EBMT study received in vivo T-cell depletion agents for GVHD prophylaxis, which could have affected relapse rates. Our analysis found that NRM was lower after MUD HCT than in the haplo cohort, which could be attributed to lower rates of primary graft failure, grade 3/4 aGVHD, and moderate/severe cGVHD, which was consistent with other studies.11,19 Unlike the previous CIBMTR analysis comparing MUD HCT and haplo-HCT with PTCy, our analysis revealed superior OS after MUD HCT using MAC, whereas OS was not different using RIC conditioning.11 Subgroup analysis stratified by disease noted variability in outcomes between donor types that aligns with previous descriptions of varying impacts across diseases.18,19 Our study may be a better representation of real-world practice given the higher number of MUD-PTCy, longer follow-up, and higher proportion of patients receiving PBSC grafts than past studies. Furthermore, the significantly larger sample size could have improved its power and ability to detect small differences between both groups.

Given that younger donor age (<30 years) has been associated with improved HCT survival and acknowledging the notable donor age difference in our cohort, we performed an unplanned subanalysis restricted to donors aged <30 years.20-23 Compared with MUDs, haplo-HCT was associated with similar OS and reduced relapse risk. This underscores a nuanced interplay between donor age and donor source. CIBMTR data show that in 2024, ∼38% of haplo-HCTs were performed with donors aged <30 years (S. Devine, oral communication, 23 June 2025), suggesting there may be opportunities to further improve outcomes, if younger donors are prioritized.

There are situations in which an individual may have availability of both MUDs and haplo donors. There has not been a clear systemic algorithm to guide donor selection in these circumstances, and the decision is heavily influenced by the transplant centers’ practice patterns. However, a recent study involving US transplant centers demonstrated that many haplo-HCT recipients were unlikely to have a MUD available.24 The Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network 1702 trial used a search prognosis–based biologic assignment algorithm to guide donor selection for patients without MRD based on being “very likely” (>2 MUDs available on search) or “very unlikely” (only mismatched donors available).25 Patients assigned to the “very likely” arm (>90%) pursued MUDs, whereas those in the “very unlikely” arm (<10%) were to use alternative donors (including haplo donors, MMUDs, or cord blood). The trial demonstrated comparable rates of transplant, time to HCT, and OS at 2 years after HCT in both groups.26,27 However, it should be noted that most of the MUD cohort (75%) of 1702 received calcineurin inhibitor–based GVHD prophylaxis due to the timeframe in which the trial accrued (2019-2022). The aforementioned trial also provides a practical approach for donor selection, recommending consideration of all donor options at initial search to ensure timely availability of a donor.

Haplo-HCT may offer certain advantages, particularly in terms of universal donor availability. Because each patient’s children and parents share 1 haplotype, and siblings have a 50% likelihood of being haplo donors, potential donors can be readily available within the family as stem cell graft source as well as for stem cell boost or donor-lymphocyte infusions. Additionally, considering second-degree relatives can further expand the donor pool and likelihood of identifying younger donors.28,29 This is particularly important for patients very unlikely to have a MUD, when short time to transplant is critical, or in patients with high risk of disease relapse.1,30 Moreover, haplo-HCT is cost-effective compared with other donor types and may be preferred in resource-limited circumstances.31,32

Given that MMUDs are a rapidly growing alternative donor source in the United States with the use of PTCy, future prospective studies comparing outcomes after MUD HCT, haplo-HCT, and MMUD HCT will be of significant interest.

Our study carries some limitations that are inherent to retrospective analyses. Any donor and conditioning regimen selection is influenced by the transplant center/physician preferences. These preferences may introduce biases in donor selection based on important patient and disease characteristics, many of which are not captured by the CIBMTR. These include capture of all factors associated with optimal disease risk stratification (presence of very high-risk mutation profiles including MECOM, TP53), comorbid conditions beyond HCT-CI score, desired timeframe to get to transplant, and MRD status. We sought to control for these as much as possible through inclusion of an IPTW sensitivity analysis for the primary end points. Although most patients received uniform PTCy GVHD prophylaxis including a calcineurin inhibitor and MMF, a minority received other combinations including sirolimus or MTX. In addition, detailed information about the causes of death, infectious complications, and HLA for haplo donors, which has been associated with survival outcomes, were not available.33 Our study is also restricted to HCT at US centers and may not apply outside the United States, because practices vary geographically.

In summary, in this retrospective registry analysis, MUD HCT with PTCy significantly decreases the risk of grade 3/4 aGVHD, moderate/severe cGVHD, and NRM, and is associated with higher OS and GRFS than haplo-HCT. These differences should be carefully weighed in the context of patient- and donor-related factors but support the prioritization of a readily available MUD over a haplo donor to ensure optimal outcomes after HCT.

Acknowledgments

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research is supported primarily by the Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; 75R60222C00011 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014-24-1-2057 and N00014-25-1-2146 from the Office of Naval Research. Support is also provided by the Medical College of Wisconsin, National Marrow Donor Program, Gateway for Cancer Research, Pediatric Transplantation and Cellular Therapy Consortium, and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Adaptimmune LLC; Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Adienne SA; Alexion; AlloVir, Inc; Amgen; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics; Autolus Limited; BeiGene; BioLineRX; Blue Spark Technologies; bluebird bio; Blueprint Medicines; Bristol Myers Squibb; CareDx; Caribou Biosciences, Inc; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics; DKMS; Editas Medicine; Elevance Health; Eurofins Viracor, DBA Eurofins Transplant Diagnostics; Gamida Cell Ltd; Gift of Life Biologics; Gift of Life Marrow Registry; HistoGenetics; In8bio, Inc; Incyte Corporation; Iovance; Janssen Research and Development, LLC; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jasper Therapeutics; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Karius; Kashi Clinical Laboratories; Kiadis Pharma; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Labcorp; Legend Biotech; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; Med Learning Group; medac GmbH; Merck & Co; Mesoblast, Inc; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co; Miller Pharmacal Group, Inc; Miltenyi Biotec; MorphoSys; MSA-EDITLife; Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Orca Biosystems, Inc; OriGen BioMedical; Ossium Health, Inc; Pfizer, Inc; Pharmacyclics, LLC, an AbbVie company; Registry Partners; Rigel Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi; Sarah Cannon; Seagen, Inc; Sobi, Inc; Sociedade Brasileira de Terapia Celular e Transplante de Medula ssea; Stemcell Technologies; Stemline Technologies; Stemsoft; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Talaris Therapeutics; Vertex Pharmaceuticals; Vor Biopharma, Inc; and Xenikos BV.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, HRSA, or any other agency of the US Government.

Authorship

Contribution: D.M., Y.M.A., T.E.D., C.B., B.E.S., S.R.S., H.E.S., J.J.A., S.M.D., F.K., and R.A. conceptualized and designed the study, and analyzed and interpreted the data; M.M.A.M., J.B.-M., M.G., A.M.J.J., H.L., F.A.M., M.M., and B.C.S. provided study materials and patients; T.E.D., C.B., J.J.A., S.M.D., and S.R.S. collected and assembled data; and all authors wrote the manuscript, approved the final manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.M. reports consulting role with ADC Therapeutics, Genmab, Bristol Myers Squibb (spouse), AstraZeneca (spouse), and Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly (spouse); and research funding from Karyopharm Therapeutics (to institution), Genentech (to institution), and AstraZeneca (to institution). T.E.D. reports a role with HealthPartners Institute (spouse). M.M.A.M. reports consulting role with CareDX, T Scan, TR1X, MaaT Pharma, and Ossium Health; and received research funding from Incyte, Stemline Therapeutics, and Takeda. J.B.-M. reports consulting role with MJH Healthcare Holdings, LLC and Avoro Capital Advisors; honoraria from Banner MD Anderson Colorado; and travel funds from Dictaforum Servicios. B.C.S. reports research funding from Genentech. B.E.S. reports consulting role with Orca Bio (to institution). J.J.A. reports consulting role with, and honoraria from, Ascella Health. S.M.D. reports a leadership role with the National Marrow Donor Program. F.K. reports research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb (to institution) and Incyte (to institution). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen R. Spellman, Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, NMDP, 500 N 5th St, Minneapolis, MN 55401; email: sspellma@nmdp.org.

References

Author notes

D.M., Y.M.A., F.K., and R.A. contributed equally to this study.

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) supports accessibility of research in accord with the National Institutes of Health data sharing policy and the National Cancer Institute Cancer Moonshot Public Access and Data Sharing Policy. The CIBMTR only releases deidentified data sets that comply with all relevant global regulations regarding privacy and confidentiality.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.