Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CART) is an effective treatment for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL) and can be curative in a subset of patients.1-4 However, 40% to 60% of patients experience disease progression or relapse after CART, resulting in poor survival outcomes with a median overall survival (OS) of 5 to 6 months.4-6 Epcoritamab and glofitamab, novel CD20 × CD3 bispecific T-cell–engaging monoclonal antibodies approved by the Food and Drug Administration, have shown remarkable efficacy for managing R/R LBCL after ≥2 lines of therapy, with overall response rates (ORRs) of 56% to 62% and complete response (CR) rates of 38% to 43%.7,8 T-cell exhaustion has been proposed as a mechanism of resistance to CART, raising the question of whether bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) are an effective therapy in patients with relapsed disease after CART.9-12 Pivotal trials examining both epcoritamab and glofitamab included a fraction of patients previously treated with CART and demonstrated a CR rate of 34% with epcoritamab (n = 61 [31%]) and 35% with glofitamab (n = 51 [33%]), with data diluted by smaller numbers of CART-refractory patients.7,8 Additionally, little is known about this subset of patients, including disease characteristics and prior lines of therapy. To our knowledge, we performed the largest retrospective analysis reported in literature examining the real-world application of BsAbs after CART failure, providing insights into disease and patient-related factors associated with response and survival outcomes.

This retrospective cohort included patients aged ≥18 years who received anti-CD19 CART (axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel, or lisocabtagene maraleucel) for R/R LBCL treatment across 14 academic centers from May 2015 through March 2024. The protocol was approved by an independent institutional review board at each institution and followed the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

We collected baseline demographics and disease characteristics at diagnosis, defining primary refractory disease (PRD) as progression or relapse within 12 months of frontline therapy and double-hit lymphoma (DHL) as dual rearrangements of MYC and BCL-2 by fluorescent in situ hybridization. We identified patients who experienced CART failure (progression or relapsed disease after CART) and collected details on subsequent therapy, including BsAb use. Data collected included disease characteristics, concomitant therapy, toxicities, response, and follow-up. Our primary objective was to determine survival outcomes with BsAbs after CART failure. Secondary objectives were to assess the impact of concomitant therapy, identify predictors of survival, and assess toxicities associated with BsAbs after CART failure. Patient-, disease-, and treatment-related characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Wilcoxon rank-sum test and pooled t test were used to determine the statistical significance of differences between variables. Follow-up data were collected till the date of last follow-up or death. Survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, assessed from the time of BsAb administration. Multivariate modeling with Cox regression was performed with selected clinical variables to determine effects on survival outcomes. A 2-sided P value <.05 was deemed statistically significant.

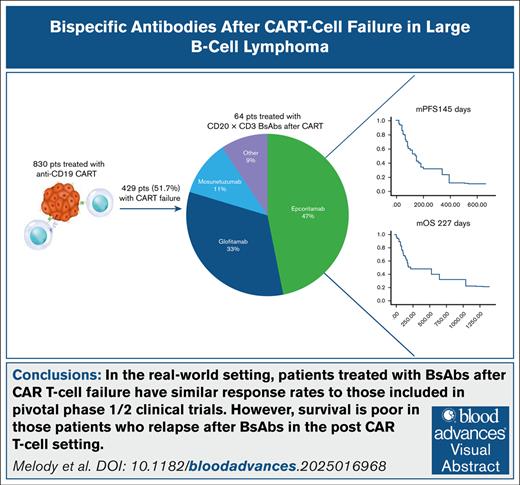

We identified 830 patients treated with anti-CD19 CART, of whom 429 (51.7%) experienced CART failure. Among these, 64 received BsAbs as salvage therapy at a median of 218 days (range, 32-2008) after CAR T-cell infusion. Patients had a median age of 64 years (range, 24-84), with the majority presenting with stage III to IV disease (n = 48 [80%]). Most patients (n = 45 [70.3%]) had de novo diffuse LBCL; 12 patients (18.8%) had DHL, detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization, 25 patients (29%) had PRD, and 3 had disease involvement of the central nervous system. Thirty-six patients underwent biopsy before initiation of treatment with BsAbs, with 33 (92%) demonstrating CD20 expression. Treatment involved epcoritamab (n = 30 [47%]), glofitamab (n = 21 [33%]), mosunetuzumab (n = 7 [11%]), and other BsAbs (n = 6 [9%]), with a median treatment duration of 4 cycles (range, 4-12). Twelve patients (19%) received adjunctive therapy in combination with BsAbs (lenalidomide, n = 6; radiation therapy, n = 2; zanubrutinib, n = 1; brentuximab vedotin, n = 1; polatuzumab, n = 1; azacitidine, n = 1).

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) occurred in 17 patients (26.6%) treated with BsAbs (grade 1, n = 10; grade 2, n = 7). Six patients received tocilizumab and 7 received steroids for CRS management. Four patients developed grade 1 immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Treatment with BsAbs resulted in an ORR of 54% (29/54 evaluable patients) and CR rate of 33% (18/54). The median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 145 days, and the median OS (mOS) was 227 days. Among CR patients, mPFS was not reached at a median follow-up of 400 days after therapy initiation, with 12 (66.7%) maintaining CR. Patients who progressed or relapsed on BsAbs had an mOS of 75 days.

No significant impact on mPFS or mOS was observed based on disease stage, presence of extranodal disease, prior exposure to bendamustine, adjunctive therapy, BsAb construct, occurrence of CRS, or use of steroids for managing BsAb-related toxicities (P = .29-1.00). Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at the time of BsAb administration was associated with inferior mPFS but not mOS (Figure 1A). Patients with PRD (n = 29 [45.3%]) or DHL (n = 12 [18.8%]) had inferior mPFS and mOS (Figure 1B-C, respectively). First-line salvage treatment with BsAbs after CART failure improved mPFS compared to use of BsAbs as salvage therapy in second line or later, although mOS was unaffected (Figure 1D). Three patients had central nervous system disease (glofitamab, n = 2; epcoritamab, n = 1) and received a median of 3 cycles of BsAb (range, 1-6), with progression of disease on therapy.

Survival outcomes of patients treated with BsAbs after CART. (A) Patients with elevated LDH had inferior mPFS compared to those without elevated LDH (mPFS = NR vs 85 days; 95% CI, 46-124; P = .01). There was no difference in mOS based on elevation in LDH (mOS = NR vs 177 days; 95% CI, 131-223; P = .13). (B) Patients with PRD had inferior mPFS and mOS compared to patients who did not have PRD (mPFS, 184 days [95% CI, 71-297] vs 85 days [95% CI, 8-162]; P = .05; mOS, 532 days [95% CI 0.0-1199] vs 161 days [95% CI 71- 251]; P = .05). (C) Presence of DHL correlated with inferior mPFS and mOS compared to without DHL (mPFS, 168 days [95% CI, 126-210] vs 80 days [95% CI, 22-138]; P = .06; mOS, 654 days [95% CI, 72-1236] vs 115 days [95% CI, 68-162]; P = .01). (D) Patients who received CD20 × CD3 BsAbs as first-line salvage after CART had improved mPFS compared to patients who received BsAbs as a later line of therapy (148 days [95% CI, 51-245] vs 103 days [95% CI, 45-161]; P = .07), but there was no difference in mOS (NR vs 187 days [95% CI, 139-235]; P = .24). CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; WNL, within normal limits.

Survival outcomes of patients treated with BsAbs after CART. (A) Patients with elevated LDH had inferior mPFS compared to those without elevated LDH (mPFS = NR vs 85 days; 95% CI, 46-124; P = .01). There was no difference in mOS based on elevation in LDH (mOS = NR vs 177 days; 95% CI, 131-223; P = .13). (B) Patients with PRD had inferior mPFS and mOS compared to patients who did not have PRD (mPFS, 184 days [95% CI, 71-297] vs 85 days [95% CI, 8-162]; P = .05; mOS, 532 days [95% CI 0.0-1199] vs 161 days [95% CI 71- 251]; P = .05). (C) Presence of DHL correlated with inferior mPFS and mOS compared to without DHL (mPFS, 168 days [95% CI, 126-210] vs 80 days [95% CI, 22-138]; P = .06; mOS, 654 days [95% CI, 72-1236] vs 115 days [95% CI, 68-162]; P = .01). (D) Patients who received CD20 × CD3 BsAbs as first-line salvage after CART had improved mPFS compared to patients who received BsAbs as a later line of therapy (148 days [95% CI, 51-245] vs 103 days [95% CI, 45-161]; P = .07), but there was no difference in mOS (NR vs 187 days [95% CI, 139-235]; P = .24). CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; WNL, within normal limits.

ORRs with BsAbs were similar among patients with CART-refractory disease (progression/failure within 90 days) and those with CART failure beyond 90 days (52.6% vs 54.3%; P = .91); however, patients with CART-refractory disease had lower CR rates with BsAbs (15.8% vs 42.9%; P = .04). Additionally, the mOS with BsAbs was significantly reduced in patients who were refractory to CART (150 vs 1045 days; P = .02). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that PRD, elevated LDH, and bulky disease at the time of BsAb administration were associated with inferior PFS, whereas inferior OS was associated with PRD, DHL, elevated LDH, and CART-refractory disease (Figure 2).

Multivariate analysis of relevant clinical variables independent effect on survival outcomes. (A) Inferior PFS was associated with bulky disease (hazard ratio [HR], 4.4; 95% CI, 1.7-11.6), elevated LDH (HR, 9.0; 95% CI, 3.0-36.4), and PRD (HR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8-11.8). (B) Inferior OS was associated with elevated LDH (HR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.1-9.5), CART-refractory disease (HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1-7.0), and DHL (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.04-8.4).

Multivariate analysis of relevant clinical variables independent effect on survival outcomes. (A) Inferior PFS was associated with bulky disease (hazard ratio [HR], 4.4; 95% CI, 1.7-11.6), elevated LDH (HR, 9.0; 95% CI, 3.0-36.4), and PRD (HR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8-11.8). (B) Inferior OS was associated with elevated LDH (HR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.1-9.5), CART-refractory disease (HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1-7.0), and DHL (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.04-8.4).

These real-world data align with the response rates for BsAbs reported in pivotal trials after CART failure. Although response rates in our cohort are comparable to those reported with alternative salvage regimens for R/R LBCL, we demonstrate more favorable survival with BsAbs after CART failure. In retrospective analyses, the anti-CD19 antibody-drug conjugate loncastuximab after CART showed a CR rate of 17%, with a median CR duration of 7.6 months and mPFS of 12 months.13 Similarly, the ECHELON-3 trial reported a 40% CR rate with the use of rituxan + lenalidomide + brentuximab-vedotin for R/R LBCL treatment, but the mPFS was only 3 months in CART-exposed patients.14

Our data provide detailed insights into clinical and disease characteristics predictive of survival with BsAbs after CART failure. We show improved response rates in patients receiving BsAbs as first-line salvage after CART failure. Additionally, CART-refractory disease was a predictor of poor survival outcomes with subsequent BsAb treatment. This may reflect a state of functional impairment or T-cell exhaustion with recent CART exposure vs aggressive disease biology. Biologic correlates are needed to complement these results and provide an understanding of mechanisms of resistance. Furthermore, patients with high tumor burden, characterized by bulky disease and/or elevated LDH, also had poorer outcomes. Collectively, these findings suggest a need for alternative treatments that are less reliant on preserved T-cell function and/or could serve as cytoreductive bridges to BsAbs. Our findings show dismal outcomes for patients with sequential failure to both CART and BsAbs, with an mOS of <3 months. Future trials evaluating novel agents should prioritize this patient population and ensure timely patient enrollment.

In conclusion, our analysis reports on, to our knowledge, the largest real-world cohort of patients receiving BsAbs after CART failure. We demonstrate that high-risk disease features, burden of disease, and timing of BsAb administration critically affect outcomes. These results establish a benchmark for the development of novel therapies and identify areas of unmet need.

Contribution: M. Melody and R.K. were responsible for study conception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the acquisition, conduct, collection, verification, and interpretation of data and revision and critical review of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M. Melody received research funding from Merck; and honoraria/consulting/advisory board fees from ADC Therapeutics (ADCT), Abbvie, BMS, Pfizer and Kite. J.R. received research funding from Merck, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, and Kymera Therapeutics; and consulting fees from Acrotech biopharma and Kyowa Kirin. M.C. reports advisory board fees from ADCT, AstraZeneca, Cellectar, and Synthekine; consultancy fees from AbbVie: and speakers bureau fees from Curio Life Sciences, Precision Oncology, and Secura Bio. T.K.M. reports advisory board fees from Seagen. R.S.B. received consulting fees from Alva10. T.O. received research support from ONO and Loxo; and consulting fees from ONO and ADCT. J.A.D. worked as a consultant for Janssen, BMS, and GSK; and as a speaker for Janssen. S.M. received research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, Juno, Loxo, and TG Therapeutics; speakers bureau fees from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, and Lilly; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Genentech, and Janssen. J.N.W. received research funding and honoraria from Merck. A.D. received consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Genentech, GenMab, Incyte, Janssen, Lilly Oncology, MEI Pharma, Merck, Nurix, and Prelude; and has ongoing research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer Oncology, BeiGene, BMS, Cyclacel, GenMab, Lilly Oncology, MEI Pharma, MorphoSys, and Nurix. S.K.B. received honoraria from Acrotech, Affimed, Daiichi Sankyo, Kyowa Kirin, Janssen, and Seagen. D.S. received consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Genentech, and Janssen; and institutional research funding from AstraZeneca and Novartis. J.B.C. received consultancy/adviser fees from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, BeiGene, Janssen, Loxo/Lilly, Kite/Gilead, and ADCT; and research funding from The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Loxo/Lilly, and BMS/Celgene. N.E. received research funding from Lilly, Beigene, ADC Therapeutics, Incyte, Ipsen and advisory board fees from CRISPR Therapeutics, Ipsen, Genentech. R.K. received advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, Gilead Sciences/Kite Pharma, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, MorphoSys/Incyte, GenMab, Avencell, Genentech/Roche, and AbbVie; and speakers bureau fees from BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and BMS. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Reem Karmali, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, 676 N Saint Clair Suite 850, Chicago, IL 60611; email: reem.karmali@northwestern.edu.

References

Author notes

Critical, deidentified data will be shared with medical experts and scientific researchers in the interest of advancing public health and are available from the corresponding author, Reem Karmali (Reem.Karmali@nm.org), on request.

![Survival outcomes of patients treated with BsAbs after CART. (A) Patients with elevated LDH had inferior mPFS compared to those without elevated LDH (mPFS = NR vs 85 days; 95% CI, 46-124; P = .01). There was no difference in mOS based on elevation in LDH (mOS = NR vs 177 days; 95% CI, 131-223; P = .13). (B) Patients with PRD had inferior mPFS and mOS compared to patients who did not have PRD (mPFS, 184 days [95% CI, 71-297] vs 85 days [95% CI, 8-162]; P = .05; mOS, 532 days [95% CI 0.0-1199] vs 161 days [95% CI 71- 251]; P = .05). (C) Presence of DHL correlated with inferior mPFS and mOS compared to without DHL (mPFS, 168 days [95% CI, 126-210] vs 80 days [95% CI, 22-138]; P = .06; mOS, 654 days [95% CI, 72-1236] vs 115 days [95% CI, 68-162]; P = .01). (D) Patients who received CD20 × CD3 BsAbs as first-line salvage after CART had improved mPFS compared to patients who received BsAbs as a later line of therapy (148 days [95% CI, 51-245] vs 103 days [95% CI, 45-161]; P = .07), but there was no difference in mOS (NR vs 187 days [95% CI, 139-235]; P = .24). CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; WNL, within normal limits.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016968/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016968-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1770926830&Signature=fDlg78bRLDMovPqRuPIyIuq7hl02vtuR1d-V3q3JD0oZFGh-Fknaofar8YjtNZTv09Yg0zGd6kPLW5va2AzEqMz7uHH6Ep-gCItcdwiEFmedoHP18~I8VnqX1xXFBQaeft6VXAAP93YInaFaDgabU6cD6V2RGHCWGiXHQ0hN9aoZrXGwvlEdPFPdr0Vi9BZ2~S~5QQ7HV4GBREp9DqdiDshoK53VduC3fMwjki81zY5r4BI5--vzSZQlXSgOnEG6KmJvucXoLDFqDzeevbqYnUOM-cToDHj38oCboLfEndfIoo3TUKXTY9vyzfYoJ1kWkoEHXp1TfJPOraXcvAEGJA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Multivariate analysis of relevant clinical variables independent effect on survival outcomes. (A) Inferior PFS was associated with bulky disease (hazard ratio [HR], 4.4; 95% CI, 1.7-11.6), elevated LDH (HR, 9.0; 95% CI, 3.0-36.4), and PRD (HR, 4.6; 95% CI, 1.8-11.8). (B) Inferior OS was associated with elevated LDH (HR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.1-9.5), CART-refractory disease (HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1-7.0), and DHL (HR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.04-8.4).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025016968/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-016968-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1770926830&Signature=CBjUhI9o5CAjddRvw2K1zptHKzncCHYFlXOTWsV8MaQxwD8p~L5ya3wsOed7faEhtlXmJrWYfXVXBz-bBhx9KfcEzXxq5-XLlRw651eSY1gzq42WJgVLJgjBfau7LgG9hztjdQlSE8w9GCBXIoQxOWZWH7Rs313qHyh6GkIqRpuRZs2U4EvAGRnv8SMoOx0WTJmZDyeJMpjDS6FSPXb1mYenzvlFxt1DTCfIptkCkaosSnDIh-VcSRwcoruGLm3sqKKBV6JWrg3mhnvl1bfwY89i1SVxKSbDx7YXhxXWhgaRfsYKnU4YrzQ3zyc2OXZK7NIYuTuTmzuNQL0goFK4Fw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)