Key Points

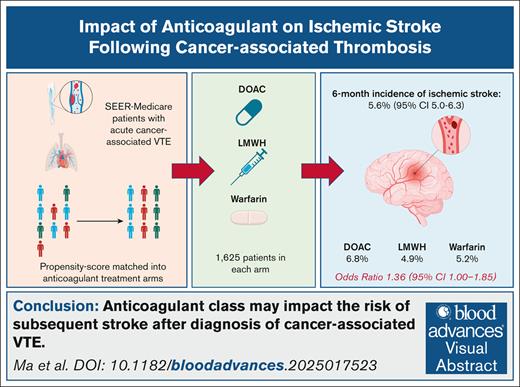

The risk of ischemic stroke is high after diagnosis of cancer-associated thrombosis despite initiation of anticoagulation.

Treatment with DOACs may be associated with a higher risk for stroke than other anticoagulant classes.

Visual Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a frequent occurrence in patients with cancer. However, it is not known whether treatment with different classes of anticoagulants impacts the risk of subsequent arterial thromboembolism. We performed a retrospective, population-based cohort study using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data linked with Medicare claims. Patients were eligible for study inclusion if they had a diagnosis of primary brain, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, lung, or ovarian cancer between 2007 and 2015, were diagnosed with VTE, and had a prescription claim for a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or warfarin. We matched patients by propensity score in a 1:1:1 ratio into anticoagulant treatment groups based on their baseline demographic information, cancer-specific characteristics, and cardiovascular comorbidities. The primary aim of the study was to determine and compare the 6-month cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke across anticoagulant classes. The study comprised 4875 total patients with 1625 in each treatment group. At 6 months, the cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.0-6.3) overall and 6.8% (95% CI, 5.6-8.1) in the DOAC, 4.9% (95% CI, 3.9-6.0) in the LMWH, and 5.2% (95% CI, 4.1-6.2) in the warfarin treatment groups (P = .040). We identified hypertension (odds ratio [OR], 1.75), atrial fibrillation/flutter (OR, 1.37), DOAC use (OR, 1.36), and previous stroke (OR, 3.59) as statistically significant risk factors for ischemic stroke in the multivariable modeling. In conclusion, ischemic stroke is a common occurrence after cancer-associated VTE and may occur more frequently in patients treated with DOACs.

Introduction

The association between cancer and venous thromboembolism (VTE) is well established, and these events contribute a significant burden of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1,2 Recent epidemiologic data have demonstrated that the incidence of arterial thromboembolism (ATE) is similarly elevated in patients with cancer.3 Reports suggest that this incidence is modulated by both the underlying cancer-specific characteristics and conventional cardiovascular risk factors.4-7 Moreover, the excess risk of ATE begins even before a cancer diagnosis and tapers toward 12 months after diagnosis, and these events portend higher short-term mortality.4,5,7-10

However, the subsequent risk of ATE among patients with acute cancer-associated VTE is not defined, nor are risk factors for ATE in this setting. Although the presence of VTE may signify a prothrombotic cancer phenotype, these patients are frequently treated with anticoagulation therapy, and it is not yet established whether this therapy may obviate the risk for an ensuing ATE. Large, randomized trials of anticoagulation therapy for the management of cancer-associated VTE have seldom reported arterial thrombosis.11-13 A recent post hoc analysis of a single-arm interventional study, which used apixaban to treat patients with acute cancer-associated VTE, reported ATE in 12 of 298 patients (4.0%) during the initial 6-month treatment period. Notably, 11 (91.7%) of these 12 events were ischemic stroke, and the ATE incidence was highest in patients with pancreatic and ovarian cancer.14 In addition, a retrospective cohort (study period 2002-2022) of 115 patients with cancer-associated, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (CA-NBTE) demonstrated a disproportionately high proportion of patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) at the time of diagnosis (28%) as opposed to on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) (14%).15 NBTE was diagnosed as the cause of ischemic stroke in 82% of patients in this study and represents an important mechanism of cancer-related stroke.3,16

These data generated the hypothesis that patients treated with DOACs for cancer-associated VTE may have an increased stroke risk when compared with patients treated with LMWH or warfarin. To that end, we conducted this population-based cohort study to define the incidence of and risk factors of ischemic stroke among patients with cancer-associated VTE.

Methods

Study design

We used a target trial emulation (TTE) framework that simulates a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using observational data by explicitly defining key trial components, including eligibility criteria, treatment initiation, follow-up, and outcomes. Supplemental Table 1 describes the key TTE protocol components pertaining to this study. This structured approach mitigates biases inherent to nonrandomized studies.17-19 By aligning treatment initiation and follow-up with real-world clinical scenarios, a TTE framework minimizes immortal time bias. In addition, we used propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics between treatment groups and mimic the randomization process of RCTs. This methodology strengthens causal inference by addressing common limitations associated with retrospective studies.

Data source

We identified qualifying patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry linked to Medicare claims. The SEER-Medicare program, established by the National Cancer Institute, comprises multiple population-based registries with coverage of approximately 28% of all patients diagnosed with cancer in the United States.20 Medicare is a federal program that provides health insurance coverage to >95% of patients aged ≥65 years.21 Linkage of individual-level data in the SEER registry with Medicare provides enrollment (parts A, B, C, and D) data, as well as claims information for inpatient, outpatient, provider services, and prescription drugs. The patient-level data in SEER-Medicare did not contain direct identifiers, and the study was approved by the institutional review board at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Study population

We included patients who were diagnosed between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2015 with colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, lung, ovarian, or brain cancer; had a qualifying VTE event contemporaneous with the cancer diagnosis, defined as either 1 month before or 6 months after the diagnosis; were aged 66 years or older and entitled to Medicare on the basis of age; were enrolled in Medicare part D for at least 3 months before the study index; survived at least 14 days after VTE diagnosis; and received a qualifying prescription claim for a DOAC, LMWH, or warfarin within 30 days of the VTE diagnosis. We selected patients with a diagnosis of cancer at these primary sites given the previously reported high rates of cancer-associated VTE identified in previous SEER-Medicare analyses.22,23 The selection of patients at this minimum age was designed to allow for sufficient time to evaluate the baseline comorbidities in Medicare claims. Although DOACs and LMWH are considered first-line agents for cancer-associated VTE, we included warfarin based on recent data that continue to demonstrate its prevalence in this setting.24 Furthermore, warfarin has demonstrated superior efficacy for stroke prevention when compared with DOACs in certain high-risk scenarios, such as rheumatic heart disease and triple positive antiphospholipid syndrome, raising interest in its activity in patients with cancer.25,26

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the upper and lower extremities (including inferior vena cava and ilia veins) and pulmonary embolism (PE) were included in this study. We identified all such qualifying events using Medicare claims that contained a previously validated International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification of the 9th (ICD-9-CM) and 10th edition (ICD-10-CM) code that defined VTE (supplemental Table 2).27 We identified all qualifying prescriptions for anticoagulants using National Drug Codes in Medicare part D claims. LMWHs included dalteparin, enoxaparin, and fondaparinux. DOACs included apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban. To account for the possibility of bridging treatment, patients whose first qualifying prescription was LMWH or heparin but then received a prescription for warfarin or a DOAC within 14 days were classified as part of the latter group. The date of the first qualifying anticoagulant was used as the study index date. We excluded patients if they had cancer stage 0, were entitled to Medicare because of disability or end-stage renal disease before the age of 65 years, or were not enrolled in a fee-for-service Medicare parts A, B, and D at the time of the study index.

Variables

For each eligible patient we obtained the demographic information (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and marital status), cancer-specific information (primary site, stage, and receipt of systemic anticancer therapy), VTE characteristics (location, year of diagnosis, and interval between cancer and VTE diagnoses), and data on previous ATEs and baseline ATE risk factors. Cancer staging was defined by criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, seventh edition. Receipt of systemic anticancer therapy was identified using the ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis and procedure codes, the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes related to chemotherapy administration, and the National Drug Codes for approved cancer therapies in part D claims.28,29 We defined active systemic anticancer treatment as occurring within 3 months of the study index.

To assess the burden of comorbidities, we calculated the Elixhauser comorbidity index score for each patient who was hospitalized at the time of the VTE diagnosis.30 Separately, we also noted the presence or absence of specific cardiovascular comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, and previous ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic arterial thromboembolism, or myocardial infarction (MI; supplemental Table 3). A comorbidity was considered as present if the patient had a corresponding ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM code in any diagnosis code position on ≥1 inpatient claim or ≥2 outpatient claims (>30 days apart) within 12 months before the study index. We defined statin use based on the National Drug Codes in Medicare part D claims.

Exposure and matching

The study exposure was the anticoagulant type at baseline (DOAC, LMWH, warfarin). To minimize imbalances between the recipients of each anticoagulant type, we used matching algorithms for the baseline characteristics. Patients were exact-matched for cancer stage and propensity-score matched using age (<75 years or ≥75 years), cancer site, year of VTE diagnosis, time from cancer diagnosis to VTE diagnosis (≤3 months or >3 month), site of VTE (DVT-only vs PE and DVT or PE-only), receipt of systemic anticancer therapy, and the cardiac comorbidities as listed previously. Patients who received DOACs were matched 1:1:1 with patients who received LMWH and warfarin using nearest-neighbor matching without replacement.

Outcomes

We defined our primary outcome as the cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke at 6 months following the study index. The 6-month time point was chosen because the cancer-associated ATE risk is attenuated after 6 to 12 months5 and because patients with cancer-associated VTE are indicated a full-dose anticoagulation for at least 3 to 6 months. Second, we also determined the cumulative incidences of MI and any ATE. Any ATE was defined as a composite of ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, MI, and systemic thromboembolism (capturing arterial embolism and thrombosis outside the coronary or cerebral vasculature). We identified all outcome events using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes on the basis of inpatient Medicare claims only (supplemental Table 4).31,32 Patients were followed from the date of their first qualifying anticoagulant prescription for 12 months or until the date of death or date of last follow-up (31 December 2016) if alive. We calculated the overall survival (OS) using the date of death extracted from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary file.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as medians with 25th and 75th percentiles for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke and other ATE outcomes was calculated overall and for each anticoagulant group and was compared using the Gray test. OS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the odds ratio (OR) of the ATE outcomes for each of the baseline variables. All analyses accounted for death as a competing risk.

We hypothesized that any difference in ischemic stroke between the anticoagulant types would be driven by a hypercoagulable state typically associated with advanced, newly diagnosed cancer and cancer types associated with NBTE.15 Accordingly, we performed prespecified subgroup analyses of the primary study outcome based on cancer stage (stage I-III vs IV), interval between cancer diagnosis and VTE diagnosis (≤3 months vs >3 months), and cancer site (gastric, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, or brain cancer vs colorectal cancer). We also performed a subgroup analysis for atrial fibrillation at baseline (yes vs no) and a sensitivity analysis that excluded those with previous ischemic stroke. The latter analysis was undertaken to assess possible ascertainment bias and to restrict the analysis to first-ever ischemic stroke event. Statistical significance was defined as a P value < .05, and all analyses were performed using R, version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

External validation of the primary outcome analysis

To add external validity to our study findings, we conducted an analysis using aggregate data from the TriNetX database, which included de-identified health records from >250 million patients across more than 140 health care institutions in 21 countries.33 In brief, we identified patients with cancer and qualifying VTE who received DOACs or LMWH between 1 January 2018 and 31 July 2024. We identified outcome ATE events using ICD-10-CM codes. We performed additional subgroup analyses by stratifying patients based on a number of characteristics, including cancer-associated VTE risk.34 Further details regarding this analysis are described in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Study population (SEER cohort)

Between 2007 and 2015, we identified a total of 12 952 eligible patients in the SEER cohort. After propensity score matching, 4875 patients with 1625 patients in each of the DOAC, LMWH, and warfarin treatment groups were included for the final analysis. Table 1 describes the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the study population after matching. Across the entire study cohort, the median age was 75 years, and 2841 (58.3%) were female. The median time between the cancer diagnosis and a qualifying VTE was 4.7 months (interquartile range, 1.2-17.5). Overall, 9.1% of the cohort were diagnosed with a VTE before the date of the cancer diagnosis. Within the DOAC group, the most common agent was rivaroxaban in 1352 (83.2%) patients. Among patients who received a LMWH, 1588 (97.7%) were treated with enoxaparin.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics after propensity score matching

| Characteristics . | Total, n (%) . | DOAC, n (%) . | Anticoagulant group . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH, n (%) . | Warfarin, n (%) . | ||||

| N = 4875 . | n = 1625 . | n = 1625 . | n = 1625 . | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 75 (70-81) | 75 (71-81) | 75 (70-80) | 75 (70-81) | .65 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2034 (42) | 667 (41) | 679 (42) | 664 (41) | .75 |

| Female | 2841 (58) | 958 (59) | 946 (58) | 961 (59) | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 4194 (86) | 1386 (85) | 1393 (86) | 1415 (87) | .68 |

| Black | 420 (9) | 146 (9) | 141 (9) | 133 (8) | |

| Other | 244 (5) | 86 (5) | 84 (5) | 74 (5) | |

| Type of VTE | |||||

| DVT without PE | 2822 (58) | 938 (58) | 926 (57) | 958 (59) | .52 |

| PE with/without DVT | 2053 (42) | 687 (42) | 699 (43) | 667 (41) | |

| Time from cancer to VTE, mo | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.7 (1.2-17.5) | 5.1 (1.2-21.0) | 4.5 (1.2-15.7) | 4.7 (1.2-16.6) | |

| ≤3 | 1886 (39) | 631 (39) | 627 (39) | 628 (39) | >.99 |

| >3 | 2989 (61) | 994 (61) | 998 (61) | 997 (61) | |

| DOAC | |||||

| Apixaban | 204 (4) | 204 (13) | — | — | N/A |

| Rivaroxaban | 1352 (28) | 1352 (83) | — | — | |

| Edoxaban | 69 (1) | 69 (4) | — | — | |

| LMWH | |||||

| Enoxaparin | 1588 (33) | — | 1588 (98) | — | N/A |

| Dalteparin or fondaparinux | 37 (1) | — | 37 (2) | — | |

| Primary cancer site | |||||

| Gastric | 158 (3) | 59 (4) | 51 (3) | 48 (4) | .97 |

| Colorectal | 1328 (27) | 446 (27) | 448 (28) | 434 (27) | |

| Pancreatic | 631 (13) | 207 (13) | 200 (12) | 224 (14) | |

| Lung | 2257 (46) | 742 (46) | 761 (47) | 754 (46) | |

| Ovarian | 360 (7) | 124 (8) | 117 (7) | 119 (7) | |

| Brain | 141 (3) | 47 (3) | 48 (3) | 46 (3) | |

| Stage | |||||

| I-II | 1623 (33) | 539 (33) | 539 (33) | 545 (34) | >.99 |

| III | 1185 (24) | 394 (24) | 394 (24) | 397 (24) | |

| IV | 1636 (34) | 551 (34) | 551 (34) | 534 (33) | |

| Not applicable | 194 (4) | 63 (4) | 63 (4) | 68 (4) | |

| Unknown | 237 (5) | 78 (5) | 78 (5) | 81 (5) | |

| Receipt of systemic anticancer therapy∗ | 2071 (42) | 679 (42) | 693 (43) | 699 (43) | .77 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index, median (range) | 3 (0-14) | 3 (0-10) | 3 (0-14) | 3 (0-11) | <.001 |

| Cardiac comorbidities | |||||

| Tobacco use | 2529 (52) | 843 (52) | 833 (51) | 853 (52) | .78 |

| Hypertension | 4129 (85) | 1377 (85) | 1376 (85) | 1376 (85) | >.99 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1401 (29) | 485 (30) | 457 (28) | 459 (28) | .49 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1501 (31) | 512 (32) | 488 (30) | 501 (31) | .66 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1462 (30) | 488 (30) | 482 (30) | 492 (30) | .93 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2131 (44) | 706 (43) | 708 (44) | 717 (44) | .92 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1191 (24) | 406 (25) | 407 (25) | 378 (23) | .41 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2065 (42) | 695 (43) | 691 (43) | 679 (42) | .84 |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 883 (18) | 307 (19) | 280 (17) | 296 (18) | .47 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 451 (9) | 161 (10) | 145 (9) | 145 (9) | .54 |

| Previous systemic thromboembolism | 233 (5) | 76 (5) | 80 (5) | 77 (5) | .96 |

| Any previous ATE | 1300 (27) | 454 (28) | 424 (26) | 422 (26) | .36 |

| Statin use | 274 (6) | 92 (6) | 96 (6) | 86 (5) | .67 |

| Atorvastatin | 179 (4) | 53 (3) | 63 (4) | 63 (4) | |

| Fluvastatin | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | — | — | |

| Lovastatin | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | — | |

| Pravastatin | 92 (2) | 37 (2) | 32 (2) | 23 (1) | |

| Characteristics . | Total, n (%) . | DOAC, n (%) . | Anticoagulant group . | P value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH, n (%) . | Warfarin, n (%) . | ||||

| N = 4875 . | n = 1625 . | n = 1625 . | n = 1625 . | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 75 (70-81) | 75 (71-81) | 75 (70-80) | 75 (70-81) | .65 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2034 (42) | 667 (41) | 679 (42) | 664 (41) | .75 |

| Female | 2841 (58) | 958 (59) | 946 (58) | 961 (59) | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 4194 (86) | 1386 (85) | 1393 (86) | 1415 (87) | .68 |

| Black | 420 (9) | 146 (9) | 141 (9) | 133 (8) | |

| Other | 244 (5) | 86 (5) | 84 (5) | 74 (5) | |

| Type of VTE | |||||

| DVT without PE | 2822 (58) | 938 (58) | 926 (57) | 958 (59) | .52 |

| PE with/without DVT | 2053 (42) | 687 (42) | 699 (43) | 667 (41) | |

| Time from cancer to VTE, mo | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.7 (1.2-17.5) | 5.1 (1.2-21.0) | 4.5 (1.2-15.7) | 4.7 (1.2-16.6) | |

| ≤3 | 1886 (39) | 631 (39) | 627 (39) | 628 (39) | >.99 |

| >3 | 2989 (61) | 994 (61) | 998 (61) | 997 (61) | |

| DOAC | |||||

| Apixaban | 204 (4) | 204 (13) | — | — | N/A |

| Rivaroxaban | 1352 (28) | 1352 (83) | — | — | |

| Edoxaban | 69 (1) | 69 (4) | — | — | |

| LMWH | |||||

| Enoxaparin | 1588 (33) | — | 1588 (98) | — | N/A |

| Dalteparin or fondaparinux | 37 (1) | — | 37 (2) | — | |

| Primary cancer site | |||||

| Gastric | 158 (3) | 59 (4) | 51 (3) | 48 (4) | .97 |

| Colorectal | 1328 (27) | 446 (27) | 448 (28) | 434 (27) | |

| Pancreatic | 631 (13) | 207 (13) | 200 (12) | 224 (14) | |

| Lung | 2257 (46) | 742 (46) | 761 (47) | 754 (46) | |

| Ovarian | 360 (7) | 124 (8) | 117 (7) | 119 (7) | |

| Brain | 141 (3) | 47 (3) | 48 (3) | 46 (3) | |

| Stage | |||||

| I-II | 1623 (33) | 539 (33) | 539 (33) | 545 (34) | >.99 |

| III | 1185 (24) | 394 (24) | 394 (24) | 397 (24) | |

| IV | 1636 (34) | 551 (34) | 551 (34) | 534 (33) | |

| Not applicable | 194 (4) | 63 (4) | 63 (4) | 68 (4) | |

| Unknown | 237 (5) | 78 (5) | 78 (5) | 81 (5) | |

| Receipt of systemic anticancer therapy∗ | 2071 (42) | 679 (42) | 693 (43) | 699 (43) | .77 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index, median (range) | 3 (0-14) | 3 (0-10) | 3 (0-14) | 3 (0-11) | <.001 |

| Cardiac comorbidities | |||||

| Tobacco use | 2529 (52) | 843 (52) | 833 (51) | 853 (52) | .78 |

| Hypertension | 4129 (85) | 1377 (85) | 1376 (85) | 1376 (85) | >.99 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1401 (29) | 485 (30) | 457 (28) | 459 (28) | .49 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1501 (31) | 512 (32) | 488 (30) | 501 (31) | .66 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1462 (30) | 488 (30) | 482 (30) | 492 (30) | .93 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2131 (44) | 706 (43) | 708 (44) | 717 (44) | .92 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1191 (24) | 406 (25) | 407 (25) | 378 (23) | .41 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2065 (42) | 695 (43) | 691 (43) | 679 (42) | .84 |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 883 (18) | 307 (19) | 280 (17) | 296 (18) | .47 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 451 (9) | 161 (10) | 145 (9) | 145 (9) | .54 |

| Previous systemic thromboembolism | 233 (5) | 76 (5) | 80 (5) | 77 (5) | .96 |

| Any previous ATE | 1300 (27) | 454 (28) | 424 (26) | 422 (26) | .36 |

| Statin use | 274 (6) | 92 (6) | 96 (6) | 86 (5) | .67 |

| Atorvastatin | 179 (4) | 53 (3) | 63 (4) | 63 (4) | |

| Fluvastatin | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | — | — | |

| Lovastatin | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | — | |

| Pravastatin | 92 (2) | 37 (2) | 32 (2) | 23 (1) | |

IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Within 3 months of study index.

The most common malignancies in the cohort were lung cancer (46.3%), colorectal cancer (27.2%), and pancreatic cancer (12.9%), and most patients in the study had advanced stage disease. Cardiac comorbidities were highly prevalent and similar across the anticoagulant treatment groups, including 13.2% with a previous ischemic stroke. Among 51.6% of patients who were hospitalized and who had a calculable Elixhauser comorbidity index, there was a numerically lower proportion of patients with an index of 1 to 2 (10.6%) in the DOAC group than in the LMWH (16.2%) or warfarin (16.2%) groups.

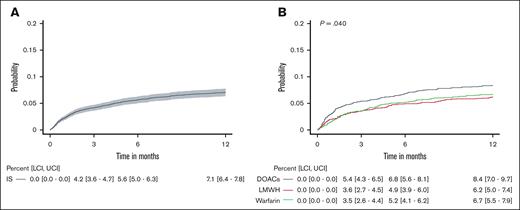

Ischemic stroke

At the 6-month follow-up, the cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke was 5.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.0-6.3) across the entire study cohort (Figure 1). The risk of stroke was highest among the DOAC-treated patients with a 6-month cumulative incidence of 6.8% (95% CI, 5.6-8.1) as opposed to 4.9% (95% CI, 3.9-6.0) and 5.2% (95% CI, 4.1-6.2) in the LMWH and warfarin groups, respectively (P = .040).

Cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke for the entire cohort (A) and separated by anticoagulant treatment group (B). The gray shading in panel A represents the 95% CIs. The black, red, and green curves denote DOACs, LMWH, and warfarin treatment, respectively, and the P value was calculated across groups using the Gray test in panel B. The tables below the figure curves show the cumulative incidence (95% CI) of ischemic stroke for the corresponding time-points. LCI, lower CI; UCI, upper CI.

Cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke for the entire cohort (A) and separated by anticoagulant treatment group (B). The gray shading in panel A represents the 95% CIs. The black, red, and green curves denote DOACs, LMWH, and warfarin treatment, respectively, and the P value was calculated across groups using the Gray test in panel B. The tables below the figure curves show the cumulative incidence (95% CI) of ischemic stroke for the corresponding time-points. LCI, lower CI; UCI, upper CI.

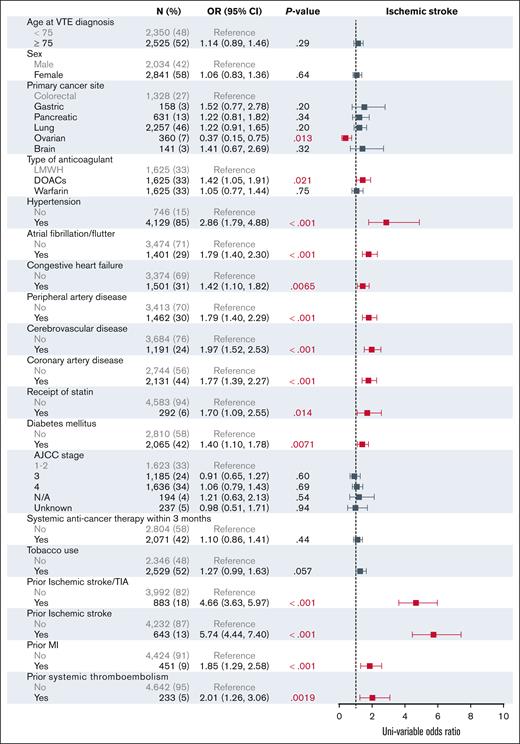

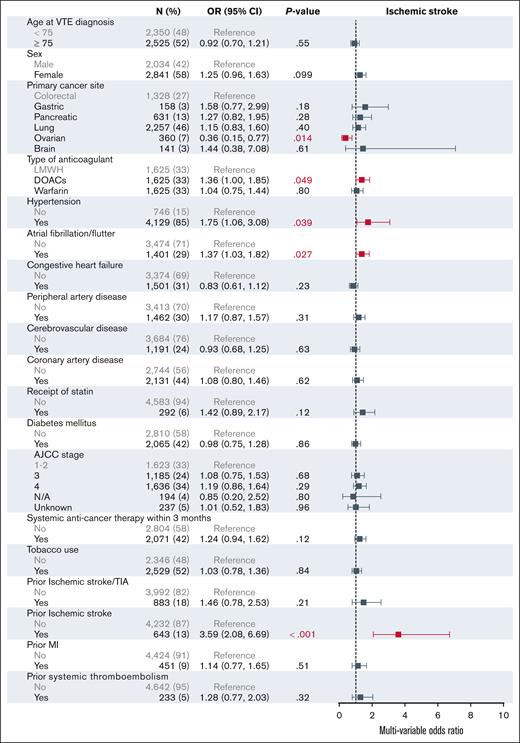

The univariable analysis of the baseline characteristics associated with ischemic stroke are shown in Figure 2. In the multivariable modeling, treatment with DOACs was associated with an increased risk for ischemic stroke (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.00-1.85) when compared with treatment with LMWH (Figure 3). Relative to colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer was associated with a decreased risk of stroke (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.15-0.77). In addition, hypertension (OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.06-3.08) and previous ischemic stroke (OR, 3.59; 95% CI, 2.08-6.69) were associated with an increased risk of stroke.

Univariable analysis for factors associated with ischemic stroke at 6 months. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; N/A, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Univariable analysis for factors associated with ischemic stroke at 6 months. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; N/A, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Multivariable analysis for factors associated with ischemic stroke at 6 months. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; N/A, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Multivariable analysis for factors associated with ischemic stroke at 6 months. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; N/A, not applicable; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Subgroup analyses

We analyzed the stroke incidence across the anticoagulant treatment groups in several prespecified subgroups. In the subgroup analysis of patients with an interval between the cancer diagnosis and the VTE diagnosis of 3 months or fewer (supplemental Figure 1), the incidence of stroke was higher among recipients of DOACs (8.6%; 95% CI, 6.4-10.7) than among recipients of LMWH (4.3%; 95% CI, 2.7-5.9) or warfarin (5.7%; 95% CI, 3.9-7.6; P = .034). In the subgroup of patients with >3 months between the cancer and VTE diagnosis, the numerical incidence of stroke in the DOAC and LMWH groups was similar and there was no statistically significant difference across the anticoagulant groups (P = .24). A similar observation was seen in the subgroup analysis by primary cancer site. In the subgroup of patients with cancer types associated with a high risk of VTE (gastric, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, or brain cancer) DOAC-treated patients had a higher stroke incidence (7.3%; 95% CI, 5.8-8.8) than patients treated with LMWH (4.6%; 95% CI, 3.4-5.8) or warfarin (5.6%; 95% CI, 4.3-6.9; P < .001). Among patients with colorectal cancer, the stroke incidence in the DOAC and LMWH groups was similar (supplemental Figure 2).

Among patients with stage IV cancer (supplemental Figure 3), we observed a significant difference in the incidence of stroke among recipients of DOACs (7.8%; 95% CI, 5.6-10.0), LMWH (4.4%; 95% CI, 2.6-6.1), and warfarin (5.6%; 95% CI, 3.7-7.6; P = .030). In patients with stage I to III cancer, although numerically higher among recipients of DOACs, the difference in stroke incidence at 6 months no longer met statistical significance among the anticoagulant groups (P = .21). Among patients with a history of atrial fibrillation/flutter (supplemental Figure 4), the incidence of stroke at 6 months was 8.1% (95% CI, 6.3-9.9). We did not observe a difference in the rate of stroke by anticoagulant type within this subgroup (P = .73).

Finally, we examined the rate of ischemic stroke among patients without a history of such diagnosis to minimize ascertainment bias in our primary outcome (supplemental Figure 5). When excluding these patients, the higher rate of stroke among recipients of DOACs (5.1%; 95% CI, 3.9-6.3) persisted when compared with treatment with LMWH (2.7%; 95% CI, 1.8-3.5) or warfarin (3.1%; 95% CI, 2.2-4.0; P = .0026).

MI and any ATE

We did not observe a statistically significant difference in the cumulative incidence of MI or any ATE among the anticoagulant treatment groups (supplemental Figures 6, 7, and 9; supplemental Results).

Survival

The median OS across the entire cohort was 10.3 months from the study index (supplemental Figure 10). Warfarin treatment (11.1 months) was associated with an increased median OS when compared with treatment with DOACs (10.9 months) or LMWH (9.3 months, P = .022).

External validation of the primary outcome analysis in the TriNetX cohort

The external validation cohort consisted of 10 941 patients in each of the DOAC and LMWH treatment groups after propensity score matching. Supplemental Table 5 describes the baseline characteristics for this cohort. The most common malignancies represented were gastrointestinal (29.6% and 29.4%), lung (18.2% and 17.9%), and hematologic (17.3% and 17.4%) across the DOAC and LMWH groups, respectively.

At 6 months of follow-up, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 38.6 events per 1000 patient-years in the DOAC group and 32.5 events per 1000 patient-years in the LMWH group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.12; 95% CI, 0.92-1.37; P = .251; supplemental Table 6). The cumulative incidence curves for ischemic stroke across the entire validation cohort and separately for the high VTE–risk malignancy cohort are shown in supplemental Figure 11.

In the subgroup analyses, DOAC use was associated with a significantly increased risk for ischemic stroke in patients with high VTE–risk malignancies (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.01-1.66; P = .040) and pancreatic cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.15-3.89; P = .014; supplemental Table 7). A trend toward an increased risk for ischemic stroke was also observed in patients with metastatic malignancies (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.93-1.72; P = .131) and gastrointestinal cancers (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.93-1.82; P = .118).

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort study that used a TTE framework, we observed a substantial rate of ATE, specifically ischemic stroke, following a diagnosis of cancer-associated VTE that was treated with anticoagulation therapy. Strikingly, our data suggest that these events occurred more frequently among patients treated with DOACs than among those treated with LMWH or warfarin, and these differences were driven by specific high-risk subgroups defined by cancer stage and site. Furthermore, these results suggest that a number of cardiovascular, but not cancer-specific, factors were predictive of stroke in the period after VTE.

An increased risk for ATE has been reported previously across heterogeneous cancer types in large epidemiologic studies. In a previous population-based study of an administrative health databases in Canada, Siegal et reported an increased HR for ischemic stroke of 1.5 (95% CI, 1.34-1.47) relative to cancer-free controls, and this observation was strongest among patients with lung cancer and stage IV disease.35 A SEER registry–based study conducted by Navi et al that compared cancer patients with matched controls similarly found the highest 3-month cumulative incidence of stroke among patients with lung cancer (5.1%; 95% CI, 4.9-5.2).36 However, relatively fewer studies have examined the incidence of ATE in the period following cancer-associated VTE and the initiation of anticoagulation, and others have specifically excluded patients treated with anticoagulation.7 In this study, we demonstrated a high incidence of ischemic stroke of 5.6% at 6 months following the initiation of anticoagulation treatment for VTE. In a previously published, multicenter prospective registry study, 1.1% of patients with cancer-associated VTE developed ATE over a median follow-up of 5.0 months with ischemic stroke comprising 66% of these events.37 In a French prospective cohort of patients with VTE, one of the few identified risk factors for ATE after anticoagulation was cancer-associated status of the index VTE.38 The high rate of ATE in this setting suggests that the presence of VTE in this population may signify an underlying prothrombotic phenotype. Indeed, in another prospective study of patients with cancer-associated VTE that reported a 6.2% cumulative incidence of ATE, ongoing anticoagulation was associated with a HR of 2.77 (95% CI, 1.07-7.22) for ATE.39 These data collectively suggest that the risk for stroke after VTE may not be adequately ameliorated by anticoagulation.

Concordant with our initial hypothesis, our data suggest that the incidence of ischemic stroke is significantly higher among patients with cancer-associated VTE who were treated with DOACs as opposed to LMWH or warfarin. The statistically significant and numerically higher rate of stroke among recipients of DOACs was also corroborated by the findings of the multivariable model that suggested that DOACs were associated with a higher OR for this event to occur (1.36). Our results further suggest that this excess stroke risk occurs within several weeks after the VTE diagnosis. This finding may have been foreshadowed by the results of the CAP study that showed a 36% rate of stroke despite treatment with apixaban in pancreatic cancer, although this trial did not include other anticoagulant treatment arms, thereby limiting comparison.14 Although a previous prospective study showed that LMWH treatment was associated with an increased risk of ATE among patients without cancer and VTE, no such association was seen with any anticoagulant class among patients with cancer-associated VTE.39 However, this study was not designed specifically to compare event-rates among anticoagulant treatment arms, and with only 5.0% receiving DOACs, it was likely underpowered to detect a difference. Although confirmation is beyond the scope of this registry-based study, one potential explanation for the higher risk of stroke among DOAC recipients may be mediated by arterial embolic complications of CA-NBTE. In a single institution retrospective study, a relatively high proportion of patients with CA-NBTE developed this disorder despite treatment with DOACs (28%) at the time of diagnosis when compared to LMWH (14%).15 This mechanism may similarly explain the lack of difference in the MI event rate among anticoagulants because this would not be expected to manifest as an embolic consequence. We emphasize that, based on subgroup analysis, the higher incidence of stroke with DOAC use was seen primarily in specific high-risk groups, including an interval between cancer and VTE diagnosis ≤3 months, stage IV cancer, and patients with gastric, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, or brain cancer. These specific groups represent higher risk factors for ATE as previously reflected in other studies,5,6,36,37 and these observations suggest that DOAC use for VTE treatment in these settings warrants caution with respect to stroke risk. Furthermore, our external validation cohort similarly corroborates the increased stroke risk with DOAC treatment in high-risk cancer subgroups.

The risk factors for the development of ATE following a cancer-associated VTE remain poorly characterized. Previous reports suggest that a previous ATE, higher cancer stage, active systemic therapy, primary cancer site (lung, gastric, pancreatic), and cardiovascular comorbidities influence the risk for ATE among cancer populations.4,5,7,8,35 In this study, we demonstrated an association between cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and previous ATE, with a higher risk of ischemic stroke. Of significant relevance to this outcome was the high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities in this study population (eg, hypertension in >80%, coronary artery disease in >40%). Given the strong association between these comorbidities and subsequent ATE in cancer populations, the high prevalence of these conditions suggests that a significant proportion of patients will be at even greater risk for ATE.37,39 Whether these specific high-risk groups warrant different approaches to ATE prevention merits further study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study specifically designed to explore the impact of anticoagulant class on the risk of subsequent ATE in patients with cancer-associated VTE. The study contains a number of key strengths. We used a TTE framework to mitigate biases common in nonrandomized studies. We performed propensity score matching to balance each anticoagulant treatment group with respect to the baseline characteristics to minimize the impact of confounding on our observed outcomes. We identified qualifying VTE events and outcome ATE events using ICD diagnosis codes that were previously validated in claims-based research. Furthermore, we performed an analysis using the TriNetX database to demonstrate external validity of the study findings. We also recognize several limitations. Despite the matched cohort study design, residual confounding may have persisted. The selection of anticoagulant class was based on individualized clinical contexts that may have biased different treatment groups toward the outcome of interest. Patients may have switched anticoagulant classes or terminated treatment earlier, which would obfuscate our comparisons between the anticoagulation arms. However, our approach may more closely approximate intention-to-treat analysis, which would likely be used in a prospective setting. We did not capture specific anticoagulant doses, but it would be reasonable to presume that therapeutic doses were prescribed given the indication of acute VTE. A significant challenge in claims-based research is the possibility of ascertainment bias when past events are inaccurately coded as a new, acute event as in this study where we did not exclude patients with past ATE to capture the impact on the risk of future ATE. However, our subgroup analysis that excluded any patients with a history of ischemic stroke continued to show a clinically significant incidence and the same significant difference between the anticoagulant treatment groups. This study did not capture the use of antiplatelet agents, which may have impacted the risk of ATE. This choice was made given that aspirin is the most commonly used agent in this class and that over-the-counter medications are not accurately captured in Medicare part D claims. Given that these agents are typically prescribed based on cardiac comorbidities, 1 goal of matching patients based on these conditions would be to potentially balance the use of antiplatelet medications. Medicare claims data have low sensitivity in measuring tobacco use, which may have confounded the analysis in our univariable and multivariable models with respect to this behavioral risk factor. The chosen study time period of 2007 to 2015 represented a period of emerging anticoagulant agents, specifically with DOAC approvals in the latter part of this period, and as such may have biased the study results. Of note, the TriNetX external validation cohort used a study period between 1 January 2018 and 31 July 2024 and found similar results. Finally, the use of the SEER-Medicare database limited our analysis to older adults above the age of 66 years and thus our findings may not be generalizable to younger cancer populations. This concern is somewhat mitigated by a mean age of 63.6 years (±14.0) in the TriNetX validation cohort, which did not limit the age of included patients.

In summary, in this population-based cohort study, we observed high rates of ATE following the diagnosis of cancer-associated VTE despite therapeutic anticoagulation, and treatment with DOACs was associated with an increased rate of ischemic stroke when compared with treatment with LMWH or warfarin, especially in specific primary cancer sites and metastatic disease. Further investigations are required to investigate the mechanisms behind these findings and delineate approaches to prevent arterial thrombosis among patients with cancer and VTE, particularly for those with additional risk factors for arterial events.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare database. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; Information Management Services, Inc; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. The visual abstract was created with BioRender.com. Ma S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/4w2b2ap.

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to the California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 1NU58DP007156; and the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) SEER Program under contract HHSN261201800032I awarded to the University of California, San Francisco, contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201800009I awarded to the Public Health Institute. J.I.Z. and A.L. were supported through National Institutes of Health/NCI Cancer Center Support grant P30 CA008748. R.P. is partially supported through Conquer Cancer Foundation.

The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their contractors and subcontractors.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M., R.P., and A.L. conceptualized the study; S.M., R.P., A.L., T.C., E.P.M., and J.I.Z. were involved in the study design; S.M., Y.-C.C., C.-H.C., J.S., Y.-C.L., K.-Y.C., and R.A.R. collected and analyzed the data; S.M., R.P., Y.-C.C., C.-H.C., and A.L. wrote the manuscript; and all authors interpreted the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare data and reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.P. reports serving as a consultant for Merck Research and Sanofi. J.I.Z. reports fees for serving on data safety monitoring boards for Sanofi and CSL Behring; and consultancy fees from Perceptive, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Regeneron. A.L. reports honoraria from Leo Pharma and Pfizer; and royalties from UpToDate. T.C. reports speaker honoraria from Takeda, Kyowa Kirin, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, and Apexcela. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Avi Leader, Hematology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; email: leadera@mskcc.org.

References

Author notes

S.M. and Y.-C.C. contributed equally to this study.

R.P. and A.L. contributed equally to this study.

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Avi Leader (leadera@mskcc.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.